My Husband’s Family BBQ, My Husband’s Sister Made a Joke: “If You Disappeared Tomorrow No One Would Even Notice.”

Part One

The Caldwell summer barbecue functioned less like a family gathering and more like a quarterly review with sauerkraut. Every year Patricia, my mother-in-law, produced glossy checklists and Pinterest boards and sent agendas disguised as “helpful notes.” Richard unveiled a new grilling gadget. The lawn looked like a catalog. Laughter carried, bright and brittle, across two acres of privilege.

I arrived with a sweating glass carrier clutched in both hands and my hope folded carefully beneath the strawberry shortcake inside. I wore a sun dress in the exact shade of the hydrangeas lining the patio because the email said “garden palette” and you learn, in this family, to treat instructions like laws if you want to breathe.

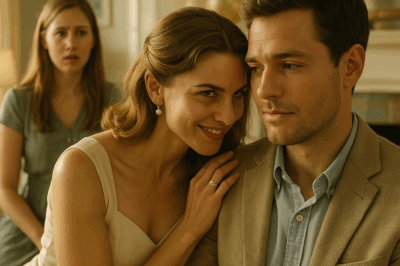

“Vanessa!” Amanda sang from the top of the stone steps, air-kissing Gregory and hovering just long enough near my cheek to smell my drugstore perfume. She looked me up and down. “That dress is so… cheerful.” Her smile didn’t reach her eyes. Patricia floated behind her like a luxury ghost. “Darling, you didn’t have to bring a thing. The pâtisserie is handling dessert.” She patted my arm in a way that suggested I was a well-meaning child who had brought a rock to show-and-tell. “Just tuck it… somewhere.” She gestured vaguely toward the pantry.

I tucked it there—on a crowded shelf beside other contributions from people who didn’t get their names on the tented place cards out on the white-clothed tables. I stood in the cool gloom of the pantry and let one breath go ragged before I arranged my face and stepped back into the bright.

For two hours I orbit-shopped for belonging. Conversations slid off me like oil. Gregory—my husband, predictable in a navy polo, his laugh half a step behind his father’s—disappeared into clusters of men who said “global” a lot. When I tried to tell Patricia that the bakery I had just branded would be in the food section of the paper next week, she blinked, glazed, then tugged my elbow so I’d hear how the widows’ committee had exceeded last quarter’s target for raffle tickets.

Charlotte, Michael’s wife, had been married in for two years and already carried a Caldwell membership badge: pediatric surgeon. She attracted solicitous questions like sugar attracts ants. I watched Patricia beam while Charlotte talked about neonatal intubation and wondered—again—when skill had become this family’s only valid currency. I wasn’t surprised. I was tired.

By the time we sat at one of the long teak tables under a trellis dripping with wisteria, my dress felt like a costume and my smile like a muscle spasm. Gregory landed across from me, already debating Japanese business etiquette with Richard because the Tokyo trip he’d just been handed mattered more than whether his wife had eaten anything but a canapé since breakfast.

The conversation eddied around Amanda, as it always did. She was midway through a story about a celebrity she had “literally run into” at her gym—she had a gift for landing herself near famous elbows—when a lull opened. I slid in.

“I just wrapped the brand for Mabel’s Bakery,” I said, aiming my voice somewhere between proud and casual. “They’re doing a 1950s-inspired neon sign. Grand opening next weekend.”

Amanda didn’t even look at me. “Is that the place with the tacky neon?” She turned her head so Patricia could hear her disdain. “We drove past it yesterday. Totally… on the nose.”

“Vintage-inspired,” I began. “The owners wanted to honor the building’s—”

“If you disappeared tomorrow,” Amanda sighed, theatrically bored, “no one would even notice. That’s how boring this conversation is.”

The laugh rose like a reflex. Patricia’s tinkled. Richard’s guffawed. Even Uncle Frank, who likely hadn’t heard the words, chuckled on cue. Gregory grinned as he reached for his beer. It took my brain a few seconds to catch up; by the time it did, my face had already arranged itself into something neutral. I felt both hypervisible and invisible—an insect under a glass on a picnic table: everyone sees you, nobody sees your panic.

I didn’t cry. I didn’t yank a linen napkin into a flag, wave it, and deliver a speech about respect. I raised my hot dog, locked eyes with Amanda, and said, clear enough for the lemon water pitchers to hear, “Challenge accepted.”

The silence that followed had teeth. then Patricia clapped twice and declared, “Who’s ready for Daddy to carve the brisket?” The universe resumed its orbit.

I spent the rest of the afternoon observing as if from the edges of a snow globe. I watched how easily they all moved through assumptions, how they had created a climate in which meeting me halfway was considered an act of charity. I watched Gregory throw me the occasional smile like a tip for good service. I cataloged each moment of being spoken over, corrected, placed. The tally matched the one I’d been keeping quietly for years.

The drive home stretched long and empty. Gregory checked emails about the Tokyo trip. “Remember,” he said without looking up, “Dad’s unveiling the imported smoker. Try to act impressed.”

As he pulled into our driveway, he glanced at me almost as an afterthought. “You’ve been quiet since lunch.”

“Amanda’s joke,” I said. “And the part where you laughed.”

He made a dismissive noise. “Don’t start. Amanda was being Amanda.”

“You laughed,” I said. “You joined in.”

“It was a joke, Vanessa.” He got out of the car. Conversation over.

At 2:00 a.m., I padded to my office and opened my laptop. I looked up apartment listings in a city two states north because my sister Olivia lived there and because it wasn’t here. I checked our joint accounts and then my small, stubborn one—the card I had opened when Gregory and I married because my mother-in-law put her name on everything. I texted Jessica—my college roommate, forever friend—and asked if she could come at nine with coffee and boxes.

By noon, the skeleton of my life lay in cardboard. I took only what was indisputably mine—clothes, personal documents, my design equipment, the recipes my grandmother had written in pencil on index cards. I transferred half of the joint account to my personal. I paid our share of the monthly bills. I wrote Gregory a letter I kept simple and adult: I need space. I took only what is mine. Please don’t contact me.

I slid my ring off and left it on top of the letter. I printed “If you disappeared tomorrow, no one would even notice,” under the date and laid that beside it because sometimes a mirror is more effective than a lecture. Then I left without looking back, because looking back is how you trip.

The hotel I chose took cash without a lecture. I turned my phone off after texting Olivia and Jessica, then slept fourteen hours with a stranger’s polyester wrapped around my shoulders like permission.

In the morning, Gregory’s messages met my screen in waves: confusion, then irritation, then the kind of concern that counts your feelings as obstacles: Call me. This is ridiculous. You’re being selfish. I have Tokyo in three days. Fine. Take your space. Amanda posted a story of the Caldwell patio with a caption that read, “Family is everything. You can’t choose who stays and who goes.” The heart emojis came as scheduled.

Seattle received me with rain. Olivia carried the largest box up the stairs to a studio apartment with a stubborn radiator and windows that made me taller just by standing in front of them. “It’s small,” she apologized. “It’s perfect,” I said, and meant it. A cocoon is supposed to be snug.

I began the quiet work of vanishing. I opened a new account at a credit union with a fern on the counter. I bought a new phone number with a new area code. I thanked Jessica for forwarding my mail but told her to stop after a month. I told my mother I was safe and asked her not to tell anyone else where. I found a therapist named Dr. Lewis whose office smelled like eucalyptus and ink; in a chair by her window, I said the words that had been rattling around my ribs with nowhere to land. I put every freelance platform I’d ever ignored to work, uploaded a portfolio stripped clean of Caldwell co-signatures, and said yes to formatting ebooks about backyard chickens and designing social media templates for yoga instructors. None of it lit my brain up like my personal work had once done. All of it paid enough for lemon and rent.

At a coffee shop with a mural of octopi wearing bowties, a barista told me the owner was looking for someone to redo the menu boards. The owner, a woman with silver-streaked hair and a handshake that had built things, hired me on the spot and handed me a condition instead of a contract: “Show me one piece of work you do every week that’s just for you,” she said. “No clients. No feedback. No apology.”

I said yes because sometimes the only way to belong to yourself again is to say yes to a stranger.

Nine months measured themselves in portfolios and better sleep. I cut my hair into a bob that made me recognize my cheekbones. I bought socks that didn’t have a single pair missing. I dated three times without writing a sonnet and realized that desire, at my age, is more about quiet than fireworks. I learned to laugh the way my sister said I used to—in my belly, not my throat.

And I learned, in the thick of my becoming, that Amanda was not a prophet. I had disappeared. The world did not end. But the part of the world that mattered to me finally began.

Part Two

Exactly a year after Amanda raised her glass and aimed her line, an email landed in my inbox from an agency called Westwood Creative. Saw your Rineer Artisan Foods rebrand in Paste Magazine. We think your aesthetic would be perfect for a national campaign with Sheffield Consumer Brands. I read it three times and then forwarded it to Olivia with nothing but the subject line: Oh.

Sheffield Consumer Brands belonged to Caldwell Marketing Group the way a hand belongs to an arm. I stared at the screen long enough to run out of adjectives. Then I did what the new version of me does when faced with a collision of past and present: I took the meeting with Westwood. I asked intelligent questions. I did not assume the universe was sending me a morality play. I prepared like a professional, not a pawn.

Three weeks later, after two rounds of concepts and a call with a Sheffield executive who didn’t care who I had once eaten deviled eggs with, Thomas—the creative director at Westwood—handed me a printed schedule for the Marketing Innovation Gala and said, “You’ll be on stage at 8:10. Try the salmon.”

I knew the Caldwells would be there. Richard attended events like this the way other men attended church. Gregory came because that’s what sons of men who attend church do. Patricia went because there were cameras. Amanda went because the world was wallpaper and she needed to be on it.

It turned out I needed to be there for a different reason: to see if I could sit in a room with my past and not leave my future on a chair.

The hotel’s lobby was full of wine and ambition. I arrived in a deep-green jumpsuit a stylist had insisted I try because “you look like a forest witch and men respect that.” Thomas introduced me to people who valued metrics more than surnames. We spoke about QR codes and environmental packaging and the way a hand reaches for the grocery shelf because some designer, years ago, loved a color enough to make it a choice.

I felt the room shift before I saw them. Richard’s laugh is an instrument; you can tune a crowd with it. I raised my glass to the level of my chin and sipped sparkling water until the bubbles reminded my hyperventilation how to behave. Richard saw me first. He approached with professional politeness.

“Vanessa,” he said, as if I had just stepped away from the buffet. “Quite a surprise.”

“Richard,” I replied, and offered him nothing to push against. “I’m the lead on Sheffield’s organic line.”

“Ah.” A pause in which a clever man recalibrates. “We hadn’t made the connection. Our in-house team will be taking things from here, of course.”

“Of course,” I agreed. “Westwood’s contracts are clear about attribution and handoff. Thomas has the paperwork.”

He nodded, and for the first time since I’d known him, looked slightly unsure about where to put his hands.

Gregory stood a polite number of feet behind his father, thinner and without the Caldwell polish that hid his queasy kindness. Our eyes met. We both did that small, human thing where two people not quite finished with being married decide not to reopen a wound over shrimp cocktail.

Amanda intercepted me outside the restrooms. She blinked—surprise, calculation, a brief flash of something softer I didn’t recognize. “No one mentioned you were involved.”

“It didn’t come up in contract negotiation,” I said, and admired my own calm.

“You always did have impeccable timing,” she said. “Reappearing exactly one year after you—” Her hand fluttered. “—left.”

“Sometimes calendars get poetic,” I said. “Sometimes they don’t. Either way, I’m here because my work belongs here.”

We looked at each other for a second that felt longer than most of our history. Then the event coordinator waved at me from the wings and I walked toward the stage.

Onstage, the lights made me a person I remembered wanting to be. My slides were clean. My sentences were sharp. I explained how the color palette echoed agricultural heritage without looking like a corporate apology for pesticides. I showed how the augmented reality feature could tell a story in a kitchen without demanding more of a mother than the minutes she had. I answered questions about rollout and shelf visibility and environmental impact in a voice that didn’t shake.

In the third row, Patricia didn’t smile. She did not frown either. I took it as respect.

After, people who once would have asked me to refill their water asked for my card. An editor asked for a quote for a round-up titled “Designers to Watch.” A woman in a jaw-dropping suit asked if I wanted to lead a panel next spring. I said yes with a steadiness that felt like muscle memory.

Gregory found me by the coffee. He said I looked well; I thanked him. He said therapy had taught him the difference between a fight and a fork in the road; I told him I hoped he learned to like his own company even when there wasn’t a deal to focus on. “Do you miss me?” he asked, not because he needed me to say yes, but because he needed his mouth to practice telling the truth.

“I miss the version of us that could have built a house separate from a family,” I said. “I don’t miss this.”

He nodded. “Me neither,” he lied kindly. We were careful with each other in that way people are when they no longer have to pretend they can pretend. We parted like colleagues. That felt correct.

Patricia cornered me in the courtyard garden between courses. “You always did have excellent timing for escapes,” she said lightly, smoothing a napkin into a triangle on her lap.

“I call it recognizing when to leave,” I replied.

“You’ve changed,” she observed.

“I’ve reverted,” I corrected. “To the woman I was before I tried to fit into yours.”

She sighed. “Families are complicated.”

“Only when people confuse loyalty with obedience,” I said, and watched her eyes flicker like a porch light at dusk.

Then it was Amanda’s turn in the quieter half of the night. She approached with the kind of caution people reserve for unfamiliar dogs. “Did you take this job because of us?” she asked, the words tumbling out with un-Amanda-like inelegance.

“I took it because it’s good work,” I said. “You aren’t a reason I do things anymore.”

It was a small knife. It didn’t bleed her. It nicked her self-importance enough to make room for something else. “Last summer,” she said, almost choking on summer. “I didn’t think you’d actually go.”

“You weren’t thinking about me at all,” I said. “That was the problem.”

She nodded like she’d practiced that motion in the mirror. “I start a parenting class next week,” she blurted. “I don’t want—” She flapped her hand again, the same motion as before, the one that meant this, all of it. “—I don’t want my child to learn the only way to be seen is to be cruel.”

“Then you’re already doing better,” I said.

She looked at me for a long second, eyes bare in a way I wouldn’t have believed a year ago. “Your work last night… it was… you were… good.”

“Thank you,” I said, as if we were women who sent each other recipe links without malice.

We didn’t hug. We didn’t promise brunch. It was enough.

After the dessert plates scraped their last and the lights went polite, I stood on the sidewalk outside the venue with my clutch under my arm listening to the city decide whether to rain again. The year had been bracketed in ways a poet would envy: a hot dog raised and a mic drop avoided; a crappy family table and a well-set industry dinner; the loud choice to leave and the quiet choice not to return.

One week later, I signed a lease on a workspace that smelled like kiln heat and ambition. Eleanor (the coffee shop owner, not my former mother-in-law) came in once a week with donuts and design critiques, which are the same thing if you squint. Olivia dragged me to a ceramics class and then out dancing in boots, and I remembered how to occupy a room with my whole body. I joined a community garden because I wanted to grow things for reasons that had nothing to do with output.

On a late morning in June, I hosted my first barbecue on a roof I shared with three plants and a neighbor named Charlie who played the saxophone at acceptable hours. I made my grandmother’s strawberry shortcake, the one that had been politely hidden in a pantry for years. I set it on the table next to Korean short ribs Eleanor had taught me to marinate and a bowl of Olivia’s potato salad, which is a crime against mayonnaise in the best possible way. People came who know my last name because they’ve asked, not because it opens anything. They told stories about deadlines and falling in love with fonts and exciting failures. We laughed from our throats and our bellies. I raised a paper cup and toasted nothing but ourselves.

“Challenge accepted,” I said to no one in particular and everyone who needed to hear it. “Challenge surpassed.”

If you’re waiting for a scene where the Caldwells show up on the sidewalk in matching expressions and ask for forgiveness, you’ll be waiting a long time. Life isn’t a morality play. They sit properly in my past now—chapter headings in a book I no longer read aloud. That’s enough of a lesson for them. This is enough of a life for me.

A year ago, at a table covered in a lifetime of someone else’s expectations, a woman made a joke about my disappearance. I took her at her word. I vanished not from the world but from theirs. Turns out the measure of a person isn’t whether certain people see you. It’s whether you can stand in your own light without squinting.

So if you ever find yourself at a barbecue with laughter that fits around your bones like a vice and someone says you’re forgettable, raise your hot dog. Tell them to watch. Then disappear. Not as an ending. As a beginning.

END!

News

It’s just a prank!” my husband smirks, soaking me in beer. His father’s shock turns to rage… CH2

“It’s just a prank!” my husband smirks, soaking me in beer. His father’s shock turns to rage… Part One…

Jesse Watters’ Personal Life EXPOSED—How He’s Balancing His High-Powered Career with Fatherhood! CH2

Jesse Watters, Fox News’ popular host, is known for his sharp political commentary, but behind the scenes, he’s also deeply…

“Welcome to our family!” she sneered, handing me a $10,000 check to leave. CH2

“Welcome to our family!” she sneered, handing me a $10,000 check to leave Part One “Welcome to the family,” Adrienne…

My brother’s fiancée dreaming of our wealth: “Just waiting for the real money,” she whispered. CH2

My Brother’s Fiancée Dreaming of Our Wealth: “Just Waiting for the Real Money,” She Whispered Part One You think you…

At the Hospital, When I Needed Surgery, Dad Took My Oxygen Mask Off —Save It for Someone Who Matters. CH2

At the Hospital, When I Needed Surgery, Dad Took My Oxygen Mask Off — “Save It for Someone Who Matters”…

On My 25th Birthday My Parents Blindfolded Me for a “Surprise”Then Dumped Me Outside a Dog Shelter. CH2

On My 25th Birthday My Parents Blindfolded Me for a “Surprise” Then Dumped Me Outside a Dog Shelter Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load