At my granddaughter’s wedding, I noticed my name tag said, “The old lady who’s paying for everything. I’m glad to have you here.”

Part 1

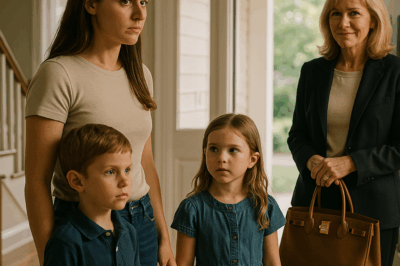

I’ve always believed that family celebrations should be moments you hold up to the light—little stained-glass panes that decorate a lifetime. My granddaughter Jennifer’s wedding was supposed to be one of those. I wore the pale blue dress Robert, my late husband, had loved. I styled my silver hair carefully, dabbed on the perfume he’d given me for our last anniversary before cancer took him. “You look beautiful, Alice,” I told my reflection in the hallway mirror, and in the quiet I could almost hear him agree. The morning’s chill lifted as sunlight swept across the old floorboards, and I let myself hope the day would be easy.

The ceremony at St. Mark’s was lovely in the way small churches can be: honest, slightly drafty, full of hymns that remind you of promises. Jennifer, radiant, walked down the aisle on my son Richard’s arm while Pamela—my daughter-in-law—dabbed at the corners of her eyes with the same grace she used to correct place settings. When Mark said “I will,” there was a hand-squeeze in the pew behind me; a neighbor, perhaps, who still remembered Robert. For those brief forty minutes, everything felt right.

It changed at the reception.

I approached the check-in table at the Westbrook Hotel, where a young woman in a headset smiled and rifled through envelopes. “Here you are, Mrs. Edwards,” she said cheerfully, handing me my name tag and table assignment.

I glanced down, expecting to see Alice Edwards — Grandmother of the Bride.

Elegant calligraphy read instead: The old lady who’s paying for everything. I’m glad to have you here.

My hand went cold around the card. “There… there seems to be a mix-up,” I said, my voice catching.

The young woman leaned over the table. Her eyes widened. “Oh my goodness. I’m so sorry. Let me see if we printed another—”

“It’s fine,” I said quickly, because forty pairs of feet were already clacking behind me and I would not be the grandmother who created a scene at her own granddaughter’s wedding. “I’ll speak with my family.”

I pinned the insult to my dress the way you pin a poppy on Remembrance Day and walked into the ballroom with my smile on straight. The chandeliers sparkled like applause; a string quartet made a pleasant fog. Guests asked about my dress, about the flowers, about Robert. A distant cousin praised the salmon canapés and wondered aloud if Jennifer had convinced me to try yoga. No one mentioned my name tag. I was grateful for them, and I felt humiliated all the same.

Then I heard it—the flick of silk, the whisper we pretend is a laugh. “Did you see the grandmother’s name tag?” someone said behind a palm. “Pamela says they thought it would be hilarious.”

“Apparently she’s their personal ATM,” came the reply.

I moved away, but the words followed me like a draft and settled between my ribs. When Richard waved me over to introduce me to an older couple—“Bill, Martha, Dad used to golf with Bill”—I went, because habit is a strong thing and I still wanted, even then, to be who they expected.

“Mom is our walking bank account,” Richard said with a laugh that made Bill wince and glance, embarrassed, at my chest. My son’s joke landed like a slap.

“Alice Edwards,” I said firmly, extending my hand. “Robert’s widow.”

Bill’s relief was immediate. “He spoke of you often,” he said. “He was very proud of you.”

“How thoughtful,” I murmured. And that was when the snapping thread inside me began to loosen from its spool.

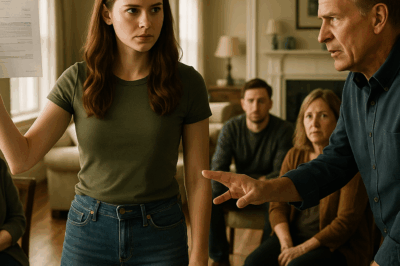

I pulled Richard aside. “What is the meaning of this?” I asked, tapping the name tag.

“Mom,” he said, rolling his eyes like a bored adolescent. “Lighten up. It’s a joke. Everyone knows you’re the one with the deep pockets since Dad left you everything.”

“It’s humiliating,” I said quietly.

“Oh, please,” Pamela chimed in, sweeping up in a storm of hairspray and pearls. “Has Richard been introducing you around? We want everyone to meet the person responsible for this gorgeous wedding.” She winked. “Gorgeous and paid-in-full.”

I excused myself and walked to the ladies’ room, where a woman of my acquaintance came in, gasped, and then backed out so quickly she almost collided with a server. I dabbed at my eyes until my attention dragged up to the mirror again. “It’s a joke,” I whispered to the woman in blue. The woman didn’t look amused.

“Mrs. Edwards?” a voice called from outside the door. “Alice?”

I opened it to find Martin Reynolds in the hallway. Robert’s attorney. A kind man with careful hands and the air of someone who can keep secrets the way old trees keep storms.

“Do you have a moment?” he asked softly, eyes flicking to my name tag and away. “Perhaps somewhere quieter?”

We found a corner near the coatroom. “You look lovely,” Martin said, then shook his head before I could wave the compliment away. “And Robert would have been furious.”

“Yes,” I said, and the single syllable felt like a room I could stand in.

“There’s something you should know.” He reached inside his jacket and brought out an envelope worn smooth by time. “Robert insisted I keep it quiet unless it became necessary. He hoped it never would.” He held it out. “It’s a codicil to his will.”

The legal language ran formal and precise across the page, but its meaning was crystalline: Any descendant who publicly humiliated me would be disinherited from their share of Robert’s fortune.

I looked up, stunned. “He never told me he did this.”

“He wanted them to treat you with respect because they loved you,” Martin said quietly, “not because they feared losing money.”

I folded the document back into the envelope and handed it to him. “Keep it,” I said. “For now.”

He nodded. “Alice—what do you want to do?”

I thought of the name tag pinned to my heart and the whispered laughter and the way I had stood patiently as Richard flicked my dignity to get a laugh. I thought of Robert, who would have thrown the card into the nearest trash and taken me by the hand into the ballroom like a queen.

“Nothing,” I said. “Not yet. I want to see how far they’ll go.”

Two days later at the brunch, I found out.

Pamela clinked her glass and announced, with the graciousness of someone volunteering charity she hadn’t raised a penny for, that I would be funding Jennifer and Mark’s two-week honeymoon to Bali. Heads swiveled. Jennifer turned pink. Mark demonstrated the admirable invisibility of a good suit.

“This is the first I’m hearing of it,” I said. It came out calm and it surprised me. It shouldn’t have. I had been practicing calm for three years.

“Mom,” Richard hissed. “We discussed it yesterday.”

“You discussed it,” I said. “I said I would think about it.”

Pamela’s smile tightened. “And you’ve done so. How wonderful.”

“No.” I set my coffee down. “I haven’t.”

I don’t know what Richard thought would happen next—perhaps the magical family force field that had always bent me would make me apologize and offer a black-card flourish. Instead, I stood. “Jennifer,” I said, meeting my granddaughter’s eyes, “privately, later, you and I will talk about a reasonable honeymoon that won’t put you or your new husband in anyone’s debt. Mark—” I nodded to him “—you and your parents will be part of that conversation too. But this—” I gestured to the room “—this is not how you ask me for money.”

Richard dragged me into the hall before Pamela could speak. “What are you doing?” he hissed. “You’re embarrassing us.”

“No,” I said, and my voice felt like a coat I’d taken out of storage and remembered fitted me. “You’ve embarrassed yourselves.”

That evening, my grandson Michael knocked on my door with the hesitant knuckles of someone who has decided to be brave.

“I wanted to apologize,” he said when I let him in. He hugged me—a solid, reassuring hug that reminded me of teenage summers when he’d eaten watermelon over the sink and tracked in grass. “For the name tag. For Dad’s announcement. I should have said something.”

“It wasn’t your responsibility,” I said. But it warmed something in me that had slept. “Would you like some tea?”

Over chamomile and roast chicken, he confessed what I had needed—and feared—to hear. He had overheard his parents discussing selling my house while I was still alive; had cataloged how the word “Mom” had turned into “asset” in their mouths the way rivers change names when they cross borders.

“I’m tired of being polite,” I told him. “But I’m going to be precise.”

“I’ll help,” he said. He met my eyes then, adult to adult. “If you want me to.”

I did.

Martin’s office smelled like lemon oil and old law. He poured me water and let me read in peace as I absorbed the documents my own assumptions had blurred for three years. Robert had left me more than comfortable. He had left me wealthy—not in the feckless, yacht-club way Richard imagined, but in the “we never have to fear a hospital bill or a deep recession” way. He had kept us safe, even after he was gone. Of course he had.

“There’s the codicil,” Martin said, sliding the envelope back into his inner pocket. “But you don’t have to use it today.”

“I know,” I said. “I’m not going to swing it like a hammer. I’m going to let it hang on the wall where they can see it and tell themselves it’s decorative.”

He smiled. “Always a painter.”

“I started classes,” I admitted, shyly proud. “It’s helping.”

“Good.” He leaned forward. “What else do you want?”

What else, indeed. The question felt like a key.

“I want to stop financing entitlement,” I said. “I want to invest in people who will build something with me instead of using me as a crutch.”

“Your grandson,” Martin said. “The bookstore.”

I laughed, because we had reached the part of the plan that would have made Pamela’s left eye twitch. “Yes. The bookstore.”

That night, Michael and I spread his business plan across my dining room table. It was smart and modest and strong. We adjusted numbers, rerouted cash flow, argued about drip coffee versus pour-over (we settled on both), and included a line item for a children’s corner full of pillows. At midnight, we poured two fingers of the bourbon Robert had put away for the day Michael graduated high school and never got to pour.

“Grandpa would have loved this,” Michael said.

“Yes,” I said. “He would have.”

Richard and Pamela didn’t respond well to boundaries. The calls escalated. The texts alternated between honeyed concern and vinegar threats. Pamela tried honey again on my birthday. Michael had invited everyone for a small family gathering at my house, which made Pamela’s smile look like a mask she had applied too tight.

“You look different,” she said, which is one of those sentences that acts like a mirror, and not a flattering one. “Did you redecorate?”

“I’m painting,” I said simply. “I sold two pieces at the community art fair.”

“Sold?” she said, at a loss, as if I had confessed to laundering money in the church font. “But why would you need—”

“It’s not need,” I said. “It’s joy.”

You could have rolled a biscuit under the door for how tight the room got. In the kitchen, as we plated cake, she cornered me. “What is going on with you?”

“I’m living my life,” I said.

“You’re funding a bookstore.” She spat the words the way people say “tattoo” when they mean “ruin.” “You’re refusing to downsize. You’re making irrational decisions.”

“Don’t mistake different for irrational,” I said. “I’m not moving into Sunrise Acres. I’m not selling my house to finance your retirement. And Michael’s bookstore is not your business.”

By the time we served dessert, Richard had reheated the conversation to a boil. “We think,” he announced, figuring democracy works best after cake is cut, “that it’s time to consider power of attorney.”

Martin set his coffee down with the kind of carefulness that precedes thunder. “Do you have evidence of diminished capacity?”

“She’s giving away money to fund a bookstore in the digital age,” Richard said, as if that sealed the matter. “And she’s refusing sensible downsizing.”

“Your mother is perfectly competent,” Martin said. “She’s making decisions you disagree with. That is not incapacity.”

“This is about protecting family,” Richard said, banging the table. “Dad would—”

“Dad did,” Martin said. He reached into his jacket, and time did that thing where it expands and turns everything into watercolor for a beat. “Robert anticipated this exact situation.” He laid the codicil on the table like a judge. “Any descendant who publicly humiliates Alice forfeits their share of Robert’s estate.”

“That’s ridiculous,” Pamela said. “You can’t—”

“We can,” Martin said. “And we have ample evidence.”

Everyone looked at me. I looked at my son—my boy who used to scrape his knee and reach for me and now reached for my checkbook—and felt the grief that goes with choosing to love someone you do not like very much.

“Yes,” I said. “Enforce it.”

Pandemonium is a word people overuse. It applies here. Richard’s face came in waves of red and white, like caution tape. Pamela’s mouth worked without sound for a stretch. Jennifer cried and apologized and then cried again. Michael stood behind my chair, not touching me, but present the way a lighthouse is present: necessary, steady.

“What happens now?” Mark asked finally, because there is always someone who is practical in a crisis, and bless him, it was the son-in-law.

“Half of Richard and Pamela’s share reverts to Alice,” Martin said. “The other half is redistributed to descendants who have demonstrated respect and care.” He turned to Michael with a smile he didn’t bother trying to hide. “Congratulations.”

“I didn’t know,” Michael said quickly, eyes on me. “I swear, Grandma, I had no idea.”

“I know,” I said. “You didn’t need to know to do the right thing.”

When the front door closed on Richard and Pamela’s last dramatic exit, when the living room settled into something like oxygen, Michael turned to me. “You okay?”

“I’m free,” I said, and I meant it, and in the saying, I became it.

Part 2

A year is a long time when you’re the one framing it. Paintings dry. Roses thicken. Granddaughters become mothers. Boys become men who juggle invoices and espresso shots and conversations with suppliers. Macramé plant hangers return to fashion, somehow. You wake up one morning and realize you’ve stopped checking your phone for arguments that will never change.

You bet on your grandson, and he opens Chapter One—a bookstore in a converted Victorian with creaky floors, shelves that make you want to run your fingers along spines, and a coffee bar where a young woman named Emma serves oat milk lattes and smiles at your grandson in a way that makes you remember being twenty. You paint a mural in the children’s corner with foxes hiding under ferns. Two afternoons a week, you lead story time and do the voices, and no one laughs at you for caring about plot.

On a Tuesday in May, Jennifer arrived with a stroller and a veil of happiness. “Hello, little Roberta,” I said, bending to greet my namesake, the baby named for her grandfather: a second-hand halo. Jennifer’s penitent year had been steady: apologizing not in paragraphs but in presence. She volunteered at the shop; she and Mark saved for a modest house on a modest street and learned how to hang shelves and argue without spending money to fix what isn’t broken. She ate the scones Emma made and brought me tealights she claimed were essential for “cozy-ness.”

“You heard from your parents?” I asked gently as we sat by the window that always seemed to find the sun.

“Mom called last week,” she said, rocking the stroller with her foot. “Same script. It’s not fair, everything’s expensive, you ruined Christmas by telling a lawyer the truth.” She rolled her eyes. “Dad got a job in Florida. They’re… out of our hair.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and meant it the way you mean the weather.

She looked out at the sidewalk where Michael was adjusting the chalkboard sign to read POETRY NIGHT — 7 PM. “Don’t be,” she said. “I’m figuring out who I am without them.”

Emma brought coffee and scones like an offering and stole a stare at Michael that made me pretend to study the foam. “More biscotti?” she offered. “You’re both my favorite customers, don’t tell the book club.”

“Liar,” I said happily. “It’s the book club. Their tab paid for that espresso machine.”

We were still laughing when Michael swooped in and kissed the top of my head. “You coming to the community board meeting later?” he asked me. “They’re discussing the grant for literacy tutoring.”

“I wouldn’t miss it,” I said. “And you’re doing the talking. I’m just decoration and scones.”

“You’re the reason they listen,” he said, and it was only after he returned to the counter that I realized I hadn’t thought of my house in months, hadn’t checked locks more than twice at bedtime, hadn’t read a text from Pamela in longer than that.

I had thought that evening would be about the board meeting and biscotti. Instead, my doorbell rang at four with something else.

Richard.

He stood on my porch the way a man does when consequence has gotten taller than he is. The Florida sun had not been kind to him; too much of it can do that to people who never learned to shade their own judgment. For a moment I saw the boy he had been, the boy who cried when he scraped both knees at once and clung to my neck like I was the only thing holding him upright. Then I remembered he was the man who had called me a selfish old woman in front of a table of friends.

“Mom,” he said. He had come alone.

I leaned against the doorjamb, hands in my cardigan pockets. “Richard.”

“I’m not here to fight,” he said, holding up his hands like we were in a bank and he’d decided last minute not to rob it. “I wanted to say… I’m sorry.”

It was quieter than a knife.

“For what?” I asked. That’s a trick I learned in therapy, and you can learn it too. Make them name the thing.

He swallowed. “For… the way I’ve treated you. For treating you like a… like a resource. For the name tag.” He managed a weak grimace. “That was Pamela. I should’ve stopped it.”

“You should have,” I said. “And calling me selfish? And the power of attorney stunt? And the attempt to move me to Sunrise Acres so you could sell my house?”

He flinched, then squared his shoulders. “Yes. For all of it.”

It didn’t change anything, not materially, not in any ledger that mattered in court, but I found a small space in me that had remained elastic and let it breathe.

“Are you sober?” I asked. It’s another trick. Answer the question you need answered, not the one you want.

He blinked. “I… yes.” He smiled humorlessly. “Florida makes you that.”

We stood like that for a long moment, our porch boards holding up more than just two people. The oak I’d planted the year Robert died cast good shade.

“I’m not asking for anything,” Richard said quickly. “I mean—I could use everything, but I’m not. I came because… because Michael invited me to Poetry Night.”

“I told him he could,” I said. “It’s his shop.”

“I figured.” He stuffed his hands in his pockets, his old tell. “Will you be there?”

“Yes,” I answered, and took mercy on both of us. “We are serving biscotti.”

He huffed something that might have been a laugh. “I’ll try not to cry.”

“You should,” I said, and left him to puzzle that out on the walk back to his car.

If there’s a version of grace I understand, it looks like a bookstore on a Thursday night with mismatched chairs and a high school senior reading a poem about his father and a forklift. It looks like Michael ceding the microphone to a shy twelve-year-old who brought haiku on index cards and Cora organizing sign-ups with the implacable fairness of an eldest child who has declared democracy and means it. It looks like Emma refilling cups with the practiced invisibility of someone who delights in facilitating.

And it looks like Richard sitting in the back, listening without talking, his grief and his disappointment rolling across his face in waves that a mother learns to read even when she wishes she didn’t.

After, he came to the counter and slid a twenty into the donation jar for the literacy program. “For the kids,” he said. “Tell your grandmother,” Emma started, then realized who he was and blushed. “I mean—tell her I, um… the lemon bars sold out.”

Richard looked at me over the rim of his paper cup and nodded once. It wasn’t absolution. It wasn’t even a ceasefire. It was something like basic civilization, which is what you need before any other kind of building can happen.

It would be neat to end here, with biscotti and poems. Life prefers messy drafts. I learned Rosalyn had been busy, even in prison.

“She’s trying to reform the financial literacy class,” Claire said one morning, holding up a printout of an article from the prison’s community newsletter. “Cites ‘recognizing manipulation patterns.’ The psychologist says it’s helping inmates look at their own decisions.”

“Good,” I said, and I meant it. Rehabilitation should rehabilitate. But I declined her calls every Wednesday at six. That door was closed.

We launched the Phoenix Foundation’s legal defense fund with a gala that felt like a reunion of refugees who had decided together not to drown. Richard Sterling’s mother spoke about what it means to hand someone your wallet and instead find your hand in theirs. A woman in a thrifted black dress read a piece she’d written about the family dinner where she refused to “lend” money she’d never be repaid and left before dessert. My speech lasted seven minutes and caused three spontaneous hugs and one very dignified standing ovation from a judge who does not stand for much.

Halfway through dessert, Claire hurried over with her tablet. “You need to see this,” she said, her whisper stabbing my calm. “Your mother—”

I took the tablet and scanned the headline: Inmate Leads Program to Teach Survivors How to Spot Financial Manipulation. There was a photo of Rosalyn in a beige uniform, hair severely tied back. She looked like a woman who had met a mirror. In a quote that crawled under my skin and refused to leave, she said, “I can’t undo what I’ve done. But I can keep someone else from doing it.”

“Good,” I said again, because there is a version of justice that doesn’t require your participation. “Let her do something useful.”

“Are you going to write her back?” Claire asked.

“No,” I said. “Not because I’m angry. Because I’m busy.”

Later, when the music had softened and the room smelled like coffee and promises, Ethan and Cora cornered me by the banner that read Transform Pain into Power. “We want to expand the youth program,” Cora said. “School presentations. Families don’t talk about this stuff until it’s too late. We can.”

“We made a checklist,” Ethan added, pulling out his phone. “Red flags. Conversation starters. A workbook kids can take home.”

“Of course you did,” I said, my heart so full it hurt. “Let’s do it. And put your names on it. Make yourselves visible.”

A month later, a letter came without a return address but with a hand I recognized from birthday cards that always arrived on the wrong day.

Alice, it began, and already I smiled, because even in prison she’d stopped pretending to claim me with a different noun.

I saw the gala on the local station they let us watch. You looked… free. I thought about the name tag at Jennifer’s wedding and wanted to die of shame. I thought about how I turned your life into a series of invoices and wanted to argue with myself. I thought about all the girls in my class who trusted people like me and wanted to teach better. I can’t ask forgiveness. I don’t deserve it. But I wanted you to know that something good is happening in a place I made ugly before. You are right to ignore my calls. Keep ignoring them. Keep building the thing you built. I will try to build something small that does not hurt anyone else.

—R.

I put the letter in the drawer with Martin’s envelope and Michael’s original business plan and the first sign Cora made for Poetry Night that spelled mic with a k. Some legacies aren’t debate clubs. They are boxes where you keep the things that built the person you’re becoming.

On the anniversary of Jennifer’s wedding—the only way I know to keep ourselves from forgetting is to mark it—we met at the garden behind the bookstore. Michael had strung fairy lights in the oak. Emma grilled corn. Jennifer brought potato salad the way Pamela had taught her and then apologized for how it tasted like memory and cumin.

I stood with my back to the tree and looked at my family. Mark bounced baby Roberta on his knee while reading a board book about colors. Michael and Emma argued good-naturedly about adding plant-based tacos to the menu. Cora had a clipboard because of course she did. Richard showed up late with cupcakes and a peace offering that looked like humility.

When the sun slipped and the garden lamps clicked on, Michael clapped his hands. “Mic without a K?” he said, winking at his sister. “For Grandma.”

Everyone groaned. I said, “Yes.”

I told them a story. About a woman who walked into a ballroom with a name tag pinned to her heart that should have crushed it. About a codicil in an envelope. About chamomile and roast chicken and a business plan on a midnight table. About a bookstore that sells both poetry and coffee. About a foundation that tells people they are not wrong to ask questions and they are not unlovable when the answers hurt.

I ended where I began, because good stories do that.

“On that day,” I said, “I thought my family had decided who I was. Today, I know better. Family is a verb. We do it or we don’t. Thank you for doing it with me.”

They raised paper cups. “To Grandmother,” someone said.

“To Alice,” said another.

“To the old lady who pays for everything,” Ethan added with a wicked grin, and Cora hit him with her clipboard, and we all laughed, and I let myself laugh hardest of all, because there is a freedom in taking back the knife someone else used on you and turning it into a key.

Later, after the lights dimmed and the street grew a hush, Michael locked the bookstore and walked me to my car. He kissed my cheek. “You okay, Grandma?”

“I’m happy,” I said, and he nodded like he would remember to check for that again.

As I drove home, I made a decision. I took the name tag—the one I had kept in my purse like shrapnel for a year—and stopped at the park next to St. Mark’s. I walked to the trash can near the bench where Robert and I used to sit after services and handed it to the past.

Then I stood in the dark and listened for a while. The night had that quality cities get in summer, when even sidewalks seem to breathe.

Once, I thought my name had been written by other people. Now, when someone asks what to write on my tag, I say, “Alice.” And when they push for more, I say, “Grandmother. Investor. Painter. Founder. Reader aloud of fox stories.”

I kept the perfume Robert gave me, because he knew how to choose things that last. I kept the house, because I wanted to. I kept my children—the ones who chose me. I kept my grandson’s bookstore key on my ring next to the one that opens the place where I make soup. I kept a letter that told me there are kinds of regret that move the world millimeters toward better.

The rest, I let go.

That is how you pay for everything that matters: with attention, with boundaries, with a name you give yourself and then live in until it fits like blue.

END!

News

Mom Abandoned Me and My Twins, Returns for My Success: But My Twins Had Something to Say! ch2

Mom Abandoned Me and My Twins, Returns for My Success: But My Twins Had Something to Say! Part 1…

My Husband Shrieked, “Our Love Is Real!” as He and His Mistress Introduced Their Child. ch2

My Husband Shrieked, “Our Love Is Real!” as He and His Mistress Introduced Their Child Part 1 I met…

My Mother Who Abandoned Me Is Back to Steal My Inheritance! ‘That Worthless Doesn’t Deserve It’. ch2

My Mother Who Abandoned Me Is Back to Steal My Inheritance! “That Worthless Doesn’t Deserve It” Part 1 I…

My Mom Canceled My Flight Abroad and Said My Place Was at Home. ch2

My Mom Canceled My Flight Abroad and Said My Place Was at Home Part 1 The email confirmation glowed on…

My Father Used My Savings For Brother’s Wedding, Saying I Won’t Need It – I Made Him Eat His Words. ch2

My Father Used My Savings For Brother’s Wedding, Saying I Won’t Need It — I Made Him Eat His Words…

My Cousins Mocked Me—Then Learned I Inherited Grandma’s $8.2M Estate. ch2

My Cousins Mocked Me—Then Learned I Inherited Grandma’s $8.2M Estate Part 1 “Oh, look. It’s the spinster with cats.” The…

End of content

No more pages to load