At my granddaughter’s wedding, I noticed my name tag said, “The old lady who’s paying for everything. I’m glad to have you here.”

Part 1

I’ve always believed that family celebrations should be moments you hold up to the light—little stained-glass panes that decorate a lifetime. My granddaughter Jennifer’s wedding was supposed to be one of those. I wore the pale blue dress Robert, my late husband, had loved. I styled my silver hair carefully, dabbed on the perfume he’d given me for our last anniversary before cancer took him. “You look beautiful, Alice,” I told my reflection in the hallway mirror, and in the quiet I could almost hear him agree. The morning’s chill lifted as sunlight swept across the old floorboards, and I let myself hope the day would be easy.

The ceremony at St. Mark’s was lovely in the way small churches can be: honest, slightly drafty, full of hymns that remind you of promises. Jennifer, radiant, walked down the aisle on my son Richard’s arm while Pamela—my daughter-in-law—dabbed at the corners of her eyes with the same grace she used to correct place settings. When Mark said “I will,” there was a hand-squeeze in the pew behind me; a neighbor, perhaps, who still remembered Robert. For those brief forty minutes, everything felt right.

It changed at the reception.

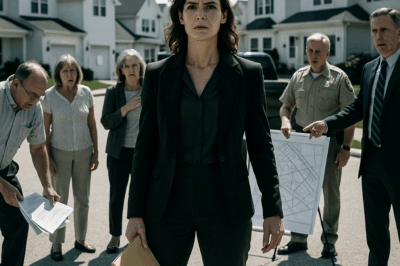

I approached the check-in table at the Westbrook Hotel, where a young woman in a headset smiled and rifled through envelopes. “Here you are, Mrs. Edwards,” she said cheerfully, handing me my name tag and table assignment.

I glanced down, expecting to see Alice Edwards — Grandmother of the Bride.

Elegant calligraphy read instead: The old lady who’s paying for everything. I’m glad to have you here.

My hand went cold around the card. “There… there seems to be a mix-up,” I said, my voice catching.

The young woman leaned over the table. Her eyes widened. “Oh my goodness. I’m so sorry. Let me see if we printed another—”

“It’s fine,” I said quickly, because forty pairs of feet were already clacking behind me and I would not be the grandmother who created a scene at her own granddaughter’s wedding. “I’ll speak with my family.”

I pinned the insult to my dress the way you pin a poppy on Remembrance Day and walked into the ballroom with my smile on straight. The chandeliers sparkled like applause; a string quartet made a pleasant fog. Guests asked about my dress, about the flowers, about Robert. A distant cousin praised the salmon canapés and wondered aloud if Jennifer had convinced me to try yoga. No one mentioned my name tag. I was grateful for them, and I felt humiliated all the same.

Then I heard it—the flick of silk, the whisper we pretend is a laugh. “Did you see the grandmother’s name tag?” someone said behind a palm. “Pamela says they thought it would be hilarious.”

“Apparently she’s their personal ATM,” came the reply.

I moved away, but the words followed me like a draft and settled between my ribs. When Richard waved me over to introduce me to an older couple—“Bill, Martha, Dad used to golf with Bill”—I went, because habit is a strong thing and I still wanted, even then, to be who they expected.

“Mom is our walking bank account,” Richard said with a laugh that made Bill wince and glance, embarrassed, at my chest. My son’s joke landed like a slap.

“Alice Edwards,” I said firmly, extending my hand. “Robert’s widow.”

Bill’s relief was immediate. “He spoke of you often,” he said. “He was very proud of you.”

“How thoughtful,” I murmured. And that was when the snapping thread inside me began to loosen from its spool.

I pulled Richard aside. “What is the meaning of this?” I asked, tapping the name tag.

“Mom,” he said, rolling his eyes like a bored adolescent. “Lighten up. It’s a joke. Everyone knows you’re the one with the deep pockets since Dad left you everything.”

“It’s humiliating,” I said quietly.

“Oh, please,” Pamela chimed in, sweeping up in a storm of hairspray and pearls. “Has Richard been introducing you around? We want everyone to meet the person responsible for this gorgeous wedding.” She winked. “Gorgeous and paid-in-full.”

I excused myself and walked to the ladies’ room, where a woman of my acquaintance came in, gasped, and then backed out so quickly she almost collided with a server. I dabbed at my eyes until my attention dragged up to the mirror again. “It’s a joke,” I whispered to the woman in blue. The woman didn’t look amused.

“Mrs. Edwards?” a voice called from outside the door. “Alice?”

I opened it to find Martin Reynolds in the hallway. Robert’s attorney. A kind man with careful hands and the air of someone who can keep secrets the way old trees keep storms.

“Do you have a moment?” he asked softly, eyes flicking to my name tag and away. “Perhaps somewhere quieter?”

We found a corner near the coatroom. “You look lovely,” Martin said, then shook his head before I could wave the compliment away. “And Robert would have been furious.”

“Yes,” I said, and the single syllable felt like a room I could stand in.

“There’s something you should know.” He reached inside his jacket and brought out an envelope worn smooth by time. “Robert insisted I keep it quiet unless it became necessary. He hoped it never would.” He held it out. “It’s a codicil to his will.”

The legal language ran formal and precise across the page, but its meaning was crystalline: Any descendant who publicly humiliated me would be disinherited from their share of Robert’s fortune.

I looked up, stunned. “He never told me he did this.”

“He wanted them to treat you with respect because they loved you,” Martin said quietly, “not because they feared losing money.”

I folded the document back into the envelope and handed it to him. “Keep it,” I said. “For now.”

He nodded. “Alice—what do you want to do?”

I thought of the name tag pinned to my heart and the whispered laughter and the way I had stood patiently as Richard flicked my dignity to get a laugh. I thought of Robert, who would have thrown the card into the nearest trash and taken me by the hand into the ballroom like a queen.

“Nothing,” I said. “Not yet. I want to see how far they’ll go.”

Two days later at the brunch, I found out.

Pamela clinked her glass and announced, with the graciousness of someone volunteering charity she hadn’t raised a penny for, that I would be funding Jennifer and Mark’s two-week honeymoon to Bali. Heads swiveled. Jennifer turned pink. Mark demonstrated the admirable invisibility of a good suit.

“This is the first I’m hearing of it,” I said. It came out calm and it surprised me. It shouldn’t have. I had been practicing calm for three years.

“Mom,” Richard hissed. “We discussed it yesterday.”

“You discussed it,” I said. “I said I would think about it.”

Pamela’s smile tightened. “And you’ve done so. How wonderful.”

“No.” I set my coffee down. “I haven’t.”

I don’t know what Richard thought would happen next—perhaps the magical family force field that had always bent me would make me apologize and offer a black-card flourish. Instead, I stood. “Jennifer,” I said, meeting my granddaughter’s eyes, “privately, later, you and I will talk about a reasonable honeymoon that won’t put you or your new husband in anyone’s debt. Mark—” I nodded to him “—you and your parents will be part of that conversation too. But this—” I gestured to the room “—this is not how you ask me for money.”

Richard dragged me into the hall before Pamela could speak. “What are you doing?” he hissed. “You’re embarrassing us.”

“No,” I said, and my voice felt like a coat I’d taken out of storage and remembered fitted me. “You’ve embarrassed yourselves.”

That evening, my grandson Michael knocked on my door with the hesitant knuckles of someone who has decided to be brave.

“I wanted to apologize,” he said when I let him in. He hugged me—a solid, reassuring hug that reminded me of teenage summers when he’d eaten watermelon over the sink and tracked in grass. “For the name tag. For Dad’s announcement. I should have said something.”

“It wasn’t your responsibility,” I said. But it warmed something in me that had slept. “Would you like some tea?”

Over chamomile and roast chicken, he confessed what I had needed—and feared—to hear. He had overheard his parents discussing selling my house while I was still alive; had cataloged how the word “Mom” had turned into “asset” in their mouths the way rivers change names when they cross borders.

“I’m tired of being polite,” I told him. “But I’m going to be precise.”

“I’ll help,” he said. He met my eyes then, adult to adult. “If you want me to.”

I did.

Martin’s office smelled like lemon oil and old law. He poured me water and let me read in peace as I absorbed the documents my own assumptions had blurred for three years. Robert had left me more than comfortable. He had left me wealthy—not in the feckless, yacht-club way Richard imagined, but in the “we never have to fear a hospital bill or a deep recession” way. He had kept us safe, even after he was gone. Of course he had.

“There’s the codicil,” Martin said, sliding the envelope back into his inner pocket. “But you don’t have to use it today.”

“I know,” I said. “I’m not going to swing it like a hammer. I’m going to let it hang on the wall where they can see it and tell themselves it’s decorative.”

He smiled. “Always a painter.”

“I started classes,” I admitted, shyly proud. “It’s helping.”

“Good.” He leaned forward. “What else do you want?”

What else, indeed. The question felt like a key.

“I want to stop financing entitlement,” I said. “I want to invest in people who will build something with me instead of using me as a crutch.”

“Your grandson,” Martin said. “The bookstore.”

I laughed, because we had reached the part of the plan that would have made Pamela’s left eye twitch. “Yes. The bookstore.”

That night, Michael and I spread his business plan across my dining room table. It was smart and modest and strong. We adjusted numbers, rerouted cash flow, argued about drip coffee versus pour-over (we settled on both), and included a line item for a children’s corner full of pillows. At midnight, we poured two fingers of the bourbon Robert had put away for the day Michael graduated high school and never got to pour.

“Grandpa would have loved this,” Michael said.

“Yes,” I said. “He would have.”

Richard and Pamela didn’t respond well to boundaries. The calls escalated. The texts alternated between honeyed concern and vinegar threats. Pamela tried honey again on my birthday. Michael had invited everyone for a small family gathering at my house, which made Pamela’s smile look like a mask she had applied too tight.

“You look different,” she said, which is one of those sentences that acts like a mirror, and not a flattering one. “Did you redecorate?”

“I’m painting,” I said simply. “I sold two pieces at the community art fair.”

“Sold?” she said, at a loss, as if I had confessed to laundering money in the church font. “But why would you need—”

“It’s not need,” I said. “It’s joy.”

You could have rolled a biscuit under the door for how tight the room got. In the kitchen, as we plated cake, she cornered me. “What is going on with you?”

“I’m living my life,” I said.

“You’re funding a bookstore.” She spat the words the way people say “tattoo” when they mean “ruin.” “You’re refusing to downsize. You’re making irrational decisions.”

“Don’t mistake different for irrational,” I said. “I’m not moving into Sunrise Acres. I’m not selling my house to finance your retirement. And Michael’s bookstore is not your business.”

By the time we served dessert, Richard had reheated the conversation to a boil. “We think,” he announced, figuring democracy works best after cake is cut, “that it’s time to consider power of attorney.”

Martin set his coffee down with the kind of carefulness that precedes thunder. “Do you have evidence of diminished capacity?”

“She’s giving away money to fund a bookstore in the digital age,” Richard said, as if that sealed the matter. “And she’s refusing sensible downsizing.”

“Your mother is perfectly competent,” Martin said. “She’s making decisions you disagree with. That is not incapacity.”

“This is about protecting family,” Richard said, banging the table. “Dad would—”

“Dad did,” Martin said. He reached into his jacket, and time did that thing where it expands and turns everything into watercolor for a beat. “Robert anticipated this exact situation.” He laid the codicil on the table like a judge. “Any descendant who publicly humiliates Alice forfeits their share of Robert’s estate.”

“That’s ridiculous,” Pamela said. “You can’t—”

“We can,” Martin said. “And we have ample evidence.”

Everyone looked at me. I looked at my son—my boy who used to scrape his knee and reach for me and now reached for my checkbook—and felt the grief that goes with choosing to love someone you do not like very much.

“Yes,” I said. “Enforce it.”

Pandemonium is a word people overuse. It applies here. Richard’s face came in waves of red and white, like caution tape. Pamela’s mouth worked without sound for a stretch. Jennifer cried and apologized and then cried again. Michael stood behind my chair, not touching me, but present the way a lighthouse is present: necessary, steady.

“What happens now?” Mark asked finally, because there is always someone who is practical in a crisis, and bless him, it was the son-in-law.

“Half of Richard and Pamela’s share reverts to Alice,” Martin said. “The other half is redistributed to descendants who have demonstrated respect and care.” He turned to Michael with a smile he didn’t bother trying to hide. “Congratulations.”

“I didn’t know,” Michael said quickly, eyes on me. “I swear, Grandma, I had no idea.”

“I know,” I said. “You didn’t need to know to do the right thing.”

When the front door closed on Richard and Pamela’s last dramatic exit, when the living room settled into something like oxygen, Michael turned to me. “You okay?”

“I’m free,” I said, and I meant it, and in the saying, I became it.

Part 2

A year is a long time when you’re the one framing it. Paintings dry. Roses thicken. Granddaughters become mothers. Boys become men who juggle invoices and espresso shots and conversations with suppliers. Macramé plant hangers return to fashion, somehow. You wake up one morning and realize you’ve stopped checking your phone for arguments that will never change.

You bet on your grandson, and he opens Chapter One—a bookstore in a converted Victorian with creaky floors, shelves that make you want to run your fingers along spines, and a coffee bar where a young woman named Emma serves oat milk lattes and smiles at your grandson in a way that makes you remember being twenty. You paint a mural in the children’s corner with foxes hiding under ferns. Two afternoons a week, you lead story time and do the voices, and no one laughs at you for caring about plot.

On a Tuesday in May, Jennifer arrived with a stroller and a veil of happiness. “Hello, little Roberta,” I said, bending to greet my namesake, the baby named for her grandfather: a second-hand halo. Jennifer’s penitent year had been steady: apologizing not in paragraphs but in presence. She volunteered at the shop; she and Mark saved for a modest house on a modest street and learned how to hang shelves and argue without spending money to fix what isn’t broken. She ate the scones Emma made and brought me tealights she claimed were essential for “cozy-ness.”

“You heard from your parents?” I asked gently as we sat by the window that always seemed to find the sun.

“Mom called last week,” she said, rocking the stroller with her foot. “Same script. It’s not fair, everything’s expensive, you ruined Christmas by telling a lawyer the truth.” She rolled her eyes. “Dad got a job in Florida. They’re… out of our hair.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and meant it the way you mean the weather.

She looked out at the sidewalk where Michael was adjusting the chalkboard sign to read POETRY NIGHT — 7 PM. “Don’t be,” she said. “I’m figuring out who I am without them.”

Emma brought coffee and scones like an offering and stole a stare at Michael that made me pretend to study the foam. “More biscotti?” she offered. “You’re both my favorite customers, don’t tell the book club.”

“Liar,” I said happily. “It’s the book club. Their tab paid for that espresso machine.”

We were still laughing when Michael swooped in and kissed the top of my head. “You coming to the community board meeting later?” he asked me. “They’re discussing the grant for literacy tutoring.”

“I wouldn’t miss it,” I said. “And you’re doing the talking. I’m just decoration and scones.”

“You’re the reason they listen,” he said, and it was only after he returned to the counter that I realized I hadn’t thought of my house in months, hadn’t checked locks more than twice at bedtime, hadn’t read a text from Pamela in longer than that.

I had thought that evening would be about the board meeting and biscotti. Instead, my doorbell rang at four with something else.

Richard.

He stood on my porch the way a man does when consequence has gotten taller than he is. The Florida sun had not been kind to him; too much of it can do that to people who never learned to shade their own judgment. For a moment I saw the boy he had been, the boy who cried when he scraped both knees at once and clung to my neck like I was the only thing holding him upright. Then I remembered he was the man who had called me a selfish old woman in front of a table of friends.

“Mom,” he said. He had come alone.

I leaned against the doorjamb, hands in my cardigan pockets. “Richard.”

“I’m not here to fight,” he said, holding up his hands like we were in a bank and he’d decided last minute not to rob it. “I wanted to say… I’m sorry.”

It was quieter than a knife.

“For what?” I asked. That’s a trick I learned in therapy, and you can learn it too. Make them name the thing.

He swallowed. “For… the way I’ve treated you. For treating you like a… like a resource. For the name tag.” He managed a weak grimace. “That was Pamela. I should’ve stopped it.”

“You should have,” I said. “And calling me selfish? And the power of attorney stunt? And the attempt to move me to Sunrise Acres so you could sell my house?”

He flinched, then squared his shoulders. “Yes. For all of it.”

It didn’t change anything, not materially, not in any ledger that mattered in court, but I found a small space in me that had remained elastic and let it breathe.

“Are you sober?” I asked. It’s another trick. Answer the question you need answered, not the one you want.

He blinked. “I… yes.” He smiled humorlessly. “Florida makes you that.”

We stood like that for a long moment, our porch boards holding up more than just two people. The oak I’d planted the year Robert died cast good shade.

“I’m not asking for anything,” Richard said quickly. “I mean—I could use everything, but I’m not. I came because… because Michael invited me to Poetry Night.”

“I told him he could,” I said. “It’s his shop.”

“I figured.” He stuffed his hands in his pockets, his old tell. “Will you be there?”

“Yes,” I answered, and took mercy on both of us. “We are serving biscotti.”

He huffed something that might have been a laugh. “I’ll try not to cry.”

“You should,” I said, and left him to puzzle that out on the walk back to his car.

If there’s a version of grace I understand, it looks like a bookstore on a Thursday night with mismatched chairs and a high school senior reading a poem about his father and a forklift. It looks like Michael ceding the microphone to a shy twelve-year-old who brought haiku on index cards and Cora organizing sign-ups with the implacable fairness of an eldest child who has declared democracy and means it. It looks like Emma refilling cups with the practiced invisibility of someone who delights in facilitating.

And it looks like Richard sitting in the back, listening without talking, his grief and his disappointment rolling across his face in waves that a mother learns to read even when she wishes she didn’t.

After, he came to the counter and slid a twenty into the donation jar for the literacy program. “For the kids,” he said. “Tell your grandmother,” Emma started, then realized who he was and blushed. “I mean—tell her I, um… the lemon bars sold out.”

Richard looked at me over the rim of his paper cup and nodded once. It wasn’t absolution. It wasn’t even a ceasefire. It was something like basic civilization, which is what you need before any other kind of building can happen.

It would be neat to end here, with biscotti and poems. Life prefers messy drafts. I learned Rosalyn had been busy, even in prison.

“She’s trying to reform the financial literacy class,” Claire said one morning, holding up a printout of an article from the prison’s community newsletter. “Cites ‘recognizing manipulation patterns.’ The psychologist says it’s helping inmates look at their own decisions.”

“Good,” I said, and I meant it. Rehabilitation should rehabilitate. But I declined her calls every Wednesday at six. That door was closed.

We launched the Phoenix Foundation’s legal defense fund with a gala that felt like a reunion of refugees who had decided together not to drown. Richard Sterling’s mother spoke about what it means to hand someone your wallet and instead find your hand in theirs. A woman in a thrifted black dress read a piece she’d written about the family dinner where she refused to “lend” money she’d never be repaid and left before dessert. My speech lasted seven minutes and caused three spontaneous hugs and one very dignified standing ovation from a judge who does not stand for much.

Halfway through dessert, Claire hurried over with her tablet. “You need to see this,” she said, her whisper stabbing my calm. “Your mother—”

I took the tablet and scanned the headline: Inmate Leads Program to Teach Survivors How to Spot Financial Manipulation. There was a photo of Rosalyn in a beige uniform, hair severely tied back. She looked like a woman who had met a mirror. In a quote that crawled under my skin and refused to leave, she said, “I can’t undo what I’ve done. But I can keep someone else from doing it.”

“Good,” I said again, because there is a version of justice that doesn’t require your participation. “Let her do something useful.”

“Are you going to write her back?” Claire asked.

“No,” I said. “Not because I’m angry. Because I’m busy.”

Later, when the music had softened and the room smelled like coffee and promises, Ethan and Cora cornered me by the banner that read Transform Pain into Power. “We want to expand the youth program,” Cora said. “School presentations. Families don’t talk about this stuff until it’s too late. We can.”

“We made a checklist,” Ethan added, pulling out his phone. “Red flags. Conversation starters. A workbook kids can take home.”

“Of course you did,” I said, my heart so full it hurt. “Let’s do it. And put your names on it. Make yourselves visible.”

A month later, a letter came without a return address but with a hand I recognized from birthday cards that always arrived on the wrong day.

Alice, it began, and already I smiled, because even in prison she’d stopped pretending to claim me with a different noun.

I saw the gala on the local station they let us watch. You looked… free. I thought about the name tag at Jennifer’s wedding and wanted to die of shame. I thought about how I turned your life into a series of invoices and wanted to argue with myself. I thought about all the girls in my class who trusted people like me and wanted to teach better. I can’t ask forgiveness. I don’t deserve it. But I wanted you to know that something good is happening in a place I made ugly before. You are right to ignore my calls. Keep ignoring them. Keep building the thing you built. I will try to build something small that does not hurt anyone else.

—R.

I put the letter in the drawer with Martin’s envelope and Michael’s original business plan and the first sign Cora made for Poetry Night that spelled mic with a k. Some legacies aren’t debate clubs. They are boxes where you keep the things that built the person you’re becoming.

On the anniversary of Jennifer’s wedding—the only way I know to keep ourselves from forgetting is to mark it—we met at the garden behind the bookstore. Michael had strung fairy lights in the oak. Emma grilled corn. Jennifer brought potato salad the way Pamela had taught her and then apologized for how it tasted like memory and cumin.

I stood with my back to the tree and looked at my family. Mark bounced baby Roberta on his knee while reading a board book about colors. Michael and Emma argued good-naturedly about adding plant-based tacos to the menu. Cora had a clipboard because of course she did. Richard showed up late with cupcakes and a peace offering that looked like humility.

When the sun slipped and the garden lamps clicked on, Michael clapped his hands. “Mic without a K?” he said, winking at his sister. “For Grandma.”

Everyone groaned. I said, “Yes.”

I told them a story. About a woman who walked into a ballroom with a name tag pinned to her heart that should have crushed it. About a codicil in an envelope. About chamomile and roast chicken and a business plan on a midnight table. About a bookstore that sells both poetry and coffee. About a foundation that tells people they are not wrong to ask questions and they are not unlovable when the answers hurt.

I ended where I began, because good stories do that.

“On that day,” I said, “I thought my family had decided who I was. Today, I know better. Family is a verb. We do it or we don’t. Thank you for doing it with me.”

They raised paper cups. “To Grandmother,” someone said.

“To Alice,” said another.

“To the old lady who pays for everything,” Ethan added with a wicked grin, and Cora hit him with her clipboard, and we all laughed, and I let myself laugh hardest of all, because there is a freedom in taking back the knife someone else used on you and turning it into a key.

Later, after the lights dimmed and the street grew a hush, Michael locked the bookstore and walked me to my car. He kissed my cheek. “You okay, Grandma?”

“I’m happy,” I said, and he nodded like he would remember to check for that again.

As I drove home, I made a decision. I took the name tag—the one I had kept in my purse like shrapnel for a year—and stopped at the park next to St. Mark’s. I walked to the trash can near the bench where Robert and I used to sit after services and handed it to the past.

Then I stood in the dark and listened for a while. The night had that quality cities get in summer, when even sidewalks seem to breathe.

Once, I thought my name had been written by other people. Now, when someone asks what to write on my tag, I say, “Alice.” And when they push for more, I say, “Grandmother. Investor. Painter. Founder. Reader aloud of fox stories.”

I kept the perfume Robert gave me, because he knew how to choose things that last. I kept the house, because I wanted to. I kept my children—the ones who chose me. I kept my grandson’s bookstore key on my ring next to the one that opens the place where I make soup. I kept a letter that told me there are kinds of regret that move the world millimeters toward better.

The rest, I let go.

That is how you pay for everything that matters: with attention, with boundaries, with a name you give yourself and then live in until it fits like blue.

Part 3

The morning after I dropped that name tag into the park trash bin, I expected to feel triumphant.

Instead, I woke up feeling… light.

Not euphoric. Not reborn. Just as if someone had finally taken a heavy purse off my shoulder that I’d been carrying so long I’d forgotten it wasn’t part of my body.

I made coffee, watered the geraniums, and sat at the kitchen table with the sun crawling slowly across the wood. My phone lay face down beside my cup. I didn’t flip it over. I knew what would be there—missed calls, half-apologies that were really accusations, texts from Pamela laced with exclamation marks like barbed wire.

I let them sit.

Outside, a delivery truck downshifted in front of Chapter One, Michael’s bookstore, across the street. He’d begged the landlord for the space three months earlier. Now it had a fresh coat of navy paint, a bell over the door that chimed like an old bicycle, and windows that always seemed to be steaming slightly from the warmth inside.

He’d chosen the name because he said that’s what it felt like—for both of us.

By ten o’clock, I was behind the counter with him, sleeves rolled, a paint-splattered apron tied around my waist. We were still learning the dance of small business: how to smile while counting change, how to recommend a book without sounding like a pushy librarian, how to pretend you weren’t terrified every time the door stayed shut for more than ten minutes.

A woman in a yellow coat came in, shook off the cold, and looked around like she’d stumbled into a closet that opened onto Narnia.

“This is new,” she said.

“We’re trying to be,” Michael replied, handing her a menu. “Coffee? Tea? Life-changing brownie?”

She laughed. “All three.”

I watched him. The same boy who’d once climbed my backyard maple with a book tucked into the back of his waistband now moved with the easy competence of someone building something with his own hands. The inheritance he hadn’t expected sat in a separate account, dull and silent. This—the smell of espresso and new paper, the murmur of people discovering stories—that was the real windfall.

Around noon, the bell dinged and Jennifer stepped in, a stroller in front of her, a diaper bag flung over one shoulder.

“Grandma,” she exhaled. “If this child ever sleeps again, it will be a miracle worthy of a plaque.”

I peeked into the stroller. A tiny face, Robert’s nose and Jennifer’s chin mashed together and softened by babyhood, furrowed in protest at the light.

“Hello, little Bobbie,” I said gently, using the nickname they’d chosen instead of Roberta. “Welcome to the library your cousin built.”

“Cousin?” Jennifer said, amused. “I feel like we need a spreadsheet to keep track of the branches now.”

Michael wiped his hands and came over. “How’s my favorite tiny human who can’t yet buy books?”

“She’d sleep better if Mark stopped tiptoeing like a burglar,” Jennifer said. “Every creak wakes her up.”

Jennifer had cried the day I told her about the codicil being enforced—tears of embarrassment, of anger, of something like relief. “I knew Mom was bad,” she’d said, “but I didn’t know how bad until she started talking about you like a line item.”

She’d chosen, quietly and steadily, to step away. She still loved her parents. She still answered their calls sometimes. But the gravitational pull they’d had on her had slackened. She and Mark paid their own rent now, saved their own money. The only thing they asked me for regularly was babysitting.

“Stay,” I said now. “Let me hold her while you drink coffee that’s still hot.”

Jennifer collapsed into the cushioned chair by the window with a gratitude that didn’t have a price tag attached. I lifted Bobbie from the stroller. Warmth and weight and that new-baby smell that makes even old grief sit up and take notice melted into my arms.

As I rocked, I caught my reflection in the glass—a woman with soft lines in her face, a smudge of flour on her sleeve from the scones we’d baked that morning, and eyes that had stopped scanning the room for insults and started looking for stories.

On my cardigan, pinned next to the little silver fox brooch Lily and I had found at a flea market, was a new name tag. The staff insisted. It read: Alice Edwards — Grandmother, Storyteller, Co-Conspirator.

I’d written the words myself.

That night, Michael taped a handwritten poster in the window: Poetry Night Every Thursday. All Ages. No Jerks.

“Do I count as a jerk if I read something from a Hallmark card?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “But you’ll do it with such charm we’ll let you stay.”

The first poetry night was chaos in the best way. A teenager in a leather jacket read a surprisingly tender sonnet about his dog. A woman my age recited a poem about her late husband’s socks that made half the room cry and the other half decide to talk to their spouses more kindly. Michael read a piece about the day he watched me walk out of Jennifer’s brunch, coffee cup steady, voice not shaking at all.

When he finished, someone started clapping slowly, then faster. I realized it was me.

Afterward, when the chairs were stacked and the chalkboard erased, when the last of the pastries had been wrapped in wax paper, the bell dinged again.

Richard stood in the doorway, hat in hand.

For a second, I saw my son as the boy who once got stage fright at his elementary school play and ran offstage into my arms, sobbing. Then the image flickered and he was the man who’d joked about his “walking bank account” to a room full of acquaintances.

“Store’s closed,” Michael said automatically, then froze when he saw who it was. “Oh. Uh. Hi, Dad.”

“I saw the sign,” Richard said, nodding at the window. “Poetry night. Thought I’d… see what this is all about.”

He was alone. No Pamela in a cloud of perfume, no entourage of friends with golf tans. His shoulders were a little rounded; the Florida real estate bubble hadn’t been kind.

Michael glanced at me, question in his eyes.

“It’s his first offense,” I said dryly. “Let him in.”

We sat at a corner table littered with coffee rings and scribbled lines. The air smelled like cinnamon and nervousness.

“I won’t stay long,” Richard said. “I just wanted to see the place. It’s nice.”

“It’s work,” Michael said. “But yeah. It’s nice.”

Richard’s gaze drifted to the mural in the children’s corner, the foxes half-hidden in painted ferns. “Mom did that,” Michael added, a hint of pride in his voice that warmed me more than the tea at my elbow.

Richard swallowed. “Of course she did.”

Silence stretched.

He cleared his throat. “I, uh, heard about the name tag. The one you threw away.”

“That late?” I said lightly. “You’re behind on your gossip.”

He flinched, then nodded. “I deserved that.”

“No,” I said. “You deserved worse. But you’re getting this.”

He looked at the ceiling, blinking hard. “I don’t expect you to forgive me,” he said. “I don’t. I just… I wanted you to know that I know. I know what I did. And I’m sorry.”

The apology wasn’t pretty. It wasn’t wrapped in the kind of self-awareness you get from therapy or late-night journaling. It was clumsy and raw. But real.

That counts.

“Are you sober?” I asked.

He blinked. “What?”

“Are you sober,” I repeated. “Because that kind of sorry only works if you remember it in the morning.”

He huffed a laugh, surprised. “Yeah,” he said. “Sober two years now. Turns out anger and bourbon don’t mix well with retirement.”

I nodded. “You could have led with that. It’s one of your better jokes.”

We talked in fits and starts. About Florida. About the job he’d taken managing a hardware store after the investment firm let him go. About how Pamela had found a circle of friends who liked outrage as much as she did and how he’d quietly stopped joining their Sunday brunches.

He didn’t ask for money. Not once.

When he left, he paused by the door. “Nice tag,” he said, nodding at my cardigan.

I looked down. Alice Edwards — Grandmother, Storyteller, Co-Conspirator.

“Thanks,” I said. “I picked it myself.”

The bell rang as he stepped into the night. I watched him go, my heart doing that strange double beat grief makes when it sits next to the possibility of something like reconciliation.

Not forgiveness. Not yet. Maybe not ever.

But something.

The next Thursday, he came back. Sat in the last row. Didn’t read. Put twenty dollars into the donation jar for the literacy program and left without making it about him.

That was enough. For now.

Years have a funny way of sneaking up on you when you stop counting the ways you’ve been wronged and start counting the ways you’ve survived.

Chapter One made it to its third anniversary. I sold five paintings at a gallery that smelled faintly of self-importance and cheese. Jennifer and Mark bought a little house with peeling trim and a garden big enough for a swing set. Baby Bobbie turned four, then five, then marched into kindergarten with a backpack that looked like it might topple her.

One afternoon, as I closed up the shop after story time, Michael handed me an envelope.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“Open it,” he said, eyes bright.

Inside was a creamy piece of cardstock with navy writing.

You are cordially invited to celebrate the marriage of Emma Martinez and Michael Edwards…

I read it twice. My throat did that irritating tightening thing it does when joy and sorrow collide.

“About time,” I said. “I was starting to worry you’d elope and rob me of my chance to judge the cake.”

“Absolutely not,” Emma said from behind the counter, where she was pretending not to eavesdrop. “We need you there to keep his family in line.”

I raised an eyebrow. “Which side?”

“Both,” she said. “In different ways.”

The wedding was set for October, in the same Westbrook Hotel that had once pinned humiliation to my chest.

“Are you sure about that?” I asked gently when Michael told me.

He shrugged. “The ballroom is pretty, the package was reasonable, and honestly? I kind of like the symmetry. We’re going back, but on our terms.”

On the day of the wedding, I stood in front of my mirror again.

Same pale blue dress, altered slightly to accommodate the ways my body and I have made peace with time. Same perfume Robert had chosen because he said it smelled like the first day of spring. Same silver hair, now a little thinner, coaxed into soft waves.

“You still clean up, old man,” I told Robert’s photo on the dresser. “Let’s go see what our boy has built.”

At the hotel check-in table, a young woman in a headset beamed at me. “Mrs. Edwards! We’ve been waiting for you.”

I smiled back, bracing myself out of habit as she handed me a name tag.

“You don’t have to wear it,” she said quickly. “But your grandson was very specific.”

I looked down.

In elegant calligraphy, it read: Alice — Patron Saint of Second Chances.

My eyes blurred. The letters swam. I swallowed.

“Is it all right?” the young woman asked nervously. “He said you’d get the joke.”

“It’s perfect,” I said. “And I do.”

The ballroom had been transformed. No towering ice sculptures, no ostentatious displays of money. Just strings of lights hung like captured constellations, tables covered in simple white linen, jars of wildflowers gathered from a field Emma’s parents had planted behind their house.

Jennifer waved from across the room, her dress a soft green, Bobbie at her side in a flower girl’s dress that had definitely seen some pre-ceremony twirling.

Richard stood near the bar, hands clasped in front of him. When he saw me, he straightened.

“Hi, Mom,” he said quietly.

“Richard,” I said. His tie was slightly crooked. I reached up and straightened it without thinking. For a second, his eyes closed.

“I told the bartender to cut me off after two club sodas,” he said, attempting humor. It landed.

“Good,” I said. “No one wants to see you try to do the Macarena again.”

He winced. “God, I’d forgotten that.”

“I hadn’t,” I said. “Some scars are stubborn.”

He laughed, then grew serious. “Thank you for being here,” he said. “For making this possible. I know Michael and Emma—”

“I didn’t pay for everything,” I interrupted. “We all did. They saved. Her parents contributed. I chipped in. Think of me as… a matching grant.”

He nodded. “Still. Thank you.”

He looked at my name tag and smiled. “They got it right.”

The ceremony was held under an arch Emma’s brothers had built from reclaimed barn wood. When Michael saw Emma walking toward him, the practiced speeches I’d heard him rehearse in the back room evaporated. He cried openly. So did Emma. So did half the room.

At the reception, there were speeches.

Emma’s father told embarrassing stories about her insistence on wearing superhero capes to church as a child. Cora—my great-niece by marriage and the de facto queen of Poetry Night—read a poem she’d written about doors and who opens them and who walks through.

Then Michael took the microphone.

“I was going to talk about Emma,” he started, “and I will, because she is the best thing that ever happened to me. But first I want to talk about someone else.”

I felt every muscle in my body tense. Old reflex.

“My grandmother,” he said.

I could have died on the spot.

He grinned at me. “She hates this, by the way. She’d rather paint foxes on walls and read to toddlers than have a room full of people look at her. But she deserves it.”

The room turned. I resisted the urge to crawl under the table with the centerpiece.

“When I was twenty-two,” he continued, “I overheard my parents talking about how my grandma’s house was ‘wasted’ on her. Like she was a line item on a spreadsheet. Like the only important thing about her was what she could fund. And I realized how wrong that was. Not just morally, but mathematically. Because if you reduce a person to what they can pay for, you have no idea what they might build with you instead.

“She invested in me—not just with money, which I didn’t even know about then, but with time and belief and story time and a mural and the kind of stubborn faith it takes to sign a lease when your hands are shaking.

“Today, this room, this wedding, this weird little life of mine—it all exists because she decided she wasn’t going to be an ATM with lipstick anymore. She was going to be Alice. My grandmother. Patron saint of second chances.

“So, Grandma, I just want to say: thank you for paying for the things that actually matter. For teaching us how to put our names on our own name tags. And for reminding us that love is not a bill we owe, but a table we sit at together.”

There was a lump in my throat the size of a dinner roll. I raised my glass because my hands needed something to do.

Later, when the dances had been danced and the cake had been cut and the DJ had moved from sentimental to deeply questionable song choices, I slipped outside for air.

The hotel garden was quiet. The same garden, I realized, where I’d once stood at another reception, fingers pressed to a cruel little piece of card stock, pretending I couldn’t feel my cheeks burn.

Tonight, the only thing pinned to my chest was a name I’d chosen and a corsage Emma had made herself.

Richard found me leaning against the balustrade, looking at the parking lot lights.

“Thought I’d find you out here,” he said.

“I needed a minute,” I said. “Your son is a menace.”

“He gets it from you,” Richard said softly.

We watched a couple sneak a kiss behind a hedge, laughing when they realized we had front-row seats.

“Do you ever regret it?” he asked suddenly.

“Regret what?” I said. There were so many potential answers he could have meant.

“Enforcing the codicil,” he said. “Cutting us off.” He looked down, toeing a crack in the paving stone. “Cutting me off.”

I considered. The easy answer—no, not for a second—rose instantly.

The harder truth came a second later.

“I don’t regret protecting myself,” I said slowly. “Or Michael. Or Jenny. I don’t regret drawing a line and saying, ‘You do not get to treat me that way and still profit from it.’”

He nodded, jaw tight.

“But,” I continued, “sometimes I regret that it had to be that way. I regret that we were people who needed a legal document to make us behave decently.”

He swallowed. “I was an ass.”

“Yes,” I said. “You were.”

He huffed a laugh. “Thanks for not sugarcoating it.”

“I’m too old for that,” I said. “My time is worth more than your comfort.”

He smiled, then sobered. “I don’t expect to be written back in, if that’s what you’re worried about. The money… it’s fine. Pamela will never forgive anyone, so that’s its own prison. I’m trying to build something else. I just…” He hesitated. “I’d like to be invited to more evenings like this. Not because you paid for them. Because you’re in them.”

I studied him. His hair was thinner. His hands, once smooth from office work, bore calluses now. There were lines at the corners of his eyes that hadn’t come from laughing.

“Keep showing up like this,” I said. “Keep not asking. Keep apologizing when you screw up. We’ll see.”

He nodded. For Richard, that was acceptance.

Inside, the DJ called out for “all the grandparents and grandkids” to come to the dance floor. Bobbie burst out the doors like a small hurricane. “Grandma!” she yelled. “They said your word!”

I laughed. “You go,” I said to Richard. “Patron saints are busy, but grandmothers dance.”

We stepped back into the light.

As I took Bobbie’s hands and spun her in clumsy circles, her dress flaring out around her like a bell, I caught a glimpse of myself in a mirrored column.

My hair was mussed. My lipstick was gone. My shoes hurt.

I have never looked more like myself.

Part 4

Getting older, I’ve learned, is a series of negotiations between your body and your pride.

“You’re dizzy because you stood up too fast,” you tell yourself after the third lightheaded spell. “You tripped because the rug caught your shoe.”

Then one day, you’re not stupid anymore. You call the doctor.

The fall happened in the kitchen on a Tuesday afternoon, because insult likes to dress itself in the ordinary.

I was reaching for the top shelf to get the good casserole dish down for lasagna night with Jennifer’s family when the floor tipped sideways. There was no cinematic warning, no slow-motion. One moment I was upright; the next I was on the tile, a sharp pain singing in my hip and my hand sticky with something that turned out, indignantly, to be tomato sauce.

“Damn,” I said, which is a word I try not to waste.

By the time the paramedics arrived—summoned by my neighbor, who’d heard the crash and the lack of follow-up swearing—the pain in my hip had gone from sharp to deep. A kind-faced EMT named Joanna kept up a steady stream of chatter as they lifted me.

“Any allergies? Medications? You got people we can call?”

“Yes. Yes. Too many. And yes,” I said. “My grandson. The one who owns the bookstore on Maple. His number’s on the fridge.”

Michael burst into the ER like a storm fifteen minutes later, hair wild, apron still on over his t-shirt.

“Grandma,” he gasped.

“It’s a small fracture,” the doctor said, before he could panic me further. “Not a full break. We’ll keep you overnight, maybe two. You’ll get to use a walker and terrorize the halls.”

Michael let out a long breath and gripped the side of the bed as if someone had told him the building might float away.

“I thought—” He stopped. “I don’t know what I thought.”

“You thought how much you’d have to learn about probate,” I said dryly. “Don’t worry. Martin and I have already taken that exam.”

His laugh broke something in me—the part that’s always braced for the moment when everyone I love leaves.

“Let me call Jennifer,” he said. “And Dad.”

Richard arrived an hour later, slightly out of breath, holding a bouquet of grocery store flowers that looked like they’d been chosen in a panic.

“You didn’t have to come,” I said.

“Shut up,” he replied, then winced. “Sorry. I mean… of course I did.”

He sat, stiff, in the corner until the nurse left us alone. Then he leaned forward, elbows on his knees.

“You scared the hell out of me, Mom,” he said. “I was halfway through some quarterly report and suddenly I remembered being ten and thinking you were invincible.”

“I never was,” I said. “I just faked it better than most.”

He nodded. “Well, don’t do that again.”

“I’ll try to schedule my next fall around your calendar,” I said. “Consulting fee applies.”

He almost smiled.

The hospital stay was short but instructive. I learned that my bones weren’t as dense as they used to be, that balance is not a guarantee, that stubbornness does not double as physical therapy, and that hospital pudding is a crime.

I also learned that my family had quietly grown around me like ivy around an old brick wall.

Jennifer brought Bobbie, who climbed carefully onto the bed and drew pictures on my arm with her finger. “This is a fox,” she announced. “And this is a book, and this is you, and this is your cane, and this is your superpower.”

“What’s my superpower?” I asked.

“Paying for everything,” she said innocently.

My heart lurched, but before I could respond, Michael spoke.

“Nope,” he said from the visitor’s chair, where he was valiantly losing at Uno to Eli from the apartment downstairs. “Try again. Grandma’s superpower is what?”

Bobbie scrunched her face. “Making people read?”

“Closer,” he said.

She lit up. “Making people feel safe.”

I swallowed around the lump. “That one,” I said. “Put that one on the cape.”

Jennifer looked at me over Bobbie’s head, eyes shining. “She came up with that on her own,” she mouthed.

Richard came every morning before work, sitting with a Sudoku book he never quite managed to focus on.

“I updated my will,” he announced on the third day, apropos of nothing.

“Oh?” I said. “Are you leaving me your collection of hideous ties?”

He snorted. “You wish.” Then he sobered. “I talked to a lawyer. Made sure Pamela can’t undo anything if… you know.” He looked at the IV pole instead of me. “I set up a small trust for Bobbie and any other grandkids, and I wrote in a clause about financial abuse. I called it the Alice Amendment.”

“That’s ridiculous,” I said, and felt tears prick my eyes.

“Ridiculously overdue,” he replied. “You shouldn’t have been the only one with a codicil.”

In the afternoons, the physical therapist—an ex-Army sergeant with a buzz cut and a heart made of equal parts grit and kindness—made me stand, shuffle, walk.

“Again,” she’d say.

“I’m eighty,” I’d reply.

“And?” she’d say.

On my last day there, as Michael went to retrieve the car and Richard argued with the billing office on my behalf (“She will pay,” I heard him say, “but you will explain every line like it’s the Bible”), Martin appeared at the foot of my bed with a folder.

“You scared me,” he said.

“Get in line,” I replied.

He handed me the folder. “While you were on your enforced vacation, I drafted something. You don’t have to sign it now. Or ever. But read it.”

It was an update to my own will.

We went through it page by page. There were bequests to the grandchildren and to Chapter One, of course. A scholarship fund for single mothers who wanted to go back to school. A modest donation to St. Mark’s for repairs and to fund the hymnals I’d loved. And a new clause, tacked to the end like punctuation.

It said that any memorial made in my name should include, in whatever form was appropriate, a reminder: that elders are not piggy banks or burdens, but full humans whose stories and boundaries deserved to be honored.

“A bit wordy,” I said. “But I like it.”

“There’s also this,” Martin said, pulling out a single sheet.

It was a letter, in my handwriting, that I had no memory of writing.

“What is that?” I asked.

“You wrote it at my office six months ago,” he said gently. “We talked about legacy. You said you wanted them to hear it from you in case you didn’t get the chance… or in case fear made you polite again.”

I took the letter.

It began: Dear children and grandchildren and whoever finds this in a lawyer’s office,

I am not a wallet. I am not a burden. I am not a hero. I am a woman who learned, too late and just in time, that the only thing you really pay for is the life you say yes to…

I skimmed a paragraph about the name tag, about boundaries, about the codicil. Then I reached the line that snagged me: If you are reading this, and you have been treating anyone—me, each other, yourself—as a means to an end instead of the end itself, stop. That inheritance is poison. I hope I’ve drained most of it before it reaches you.

By the time I reached the last sentence—Spend love like it’s the only currency that inflates—I was crying.

“Do you want to change anything?” Martin asked quietly.

“No,” I said, voice rough. “I want to live long enough to make half of it unnecessary. But if I don’t, this will do.”

At home, the walker felt both like defeat and like freedom. I hated its rattling presence, the way it announced me before I rounded corners. But I loved that it kept me upright. Pride adjusts, if you let it.

The fall, irritatingly, made me a bit of a celebrity at the senior center.

“How’d you do it?” a man named Frank asked. “Wet tile? Loose rug? Tripping over grandkids?”

“Cooking,” I said. “The lasagna won.”

He winced. “At least it wasn’t for nothing.”

When the social worker at the center learned about my work at the bookstore and my history with the codicil, she asked if I’d consider leading a workshop series.

“On what?” I asked. “How not to break your hip?”

She smiled. “On financial boundaries. On saying no. On recognizing when ‘helping’ is actually ‘being used.’”

The first session, we expected a handful of people. Thirty showed up. We ran out of chairs.

I watched them shuffle in—women with carefully done hair, men with calloused hands, couples who held on to each other like driftwood. Some clutched notebooks. Others held nothing but their own bracing.

“Hi,” I said, standing at the front with my walker like a podium. “My name is Alice. Once, at my granddaughter’s wedding, I was introduced to the world as ‘the old lady who’s paying for everything.’”

There were gasps. A few bitter laughs of recognition.

“I’m here to tell you,” I continued, “that you don’t owe anyone your dignity as a down payment for their affection.”

We talked for an hour. About guilt. About manipulation. About the way love is weaponized by people who are afraid of scarcity. We role-played saying no. We wrote scripts and set them on fire in a metal trash can outside like teenagers with secrets.

Halfway through, a woman near the back raised her hand.

“My son says if I don’t help him with his mortgage, he’ll have to move and I won’t see my grandkids as much,” she said. Her voice shook. “Am I a bad mother if I say no?”

“You’re a better grandmother if you let his consequences be his own,” I said gently. “Visiting is a choice. So is making your aging mother responsible for your lifestyle. You can love your grandkids and still protect your retirement.”

She cried. Others put hands on her shoulders. It felt like church, the kind that feeds instead of starves.

We ended the series with a simple ritual. I brought in a stack of blank name tags.

“Write down,” I said, “a name you’ve been called that hurt you. Or a role you’ve been stuck in that you don’t want anymore. Stick it on this poster.”

They came up slowly at first, then like a tide.

“Nag,” one tag read.

“Burden.”

“Bank.”

“Difficult.”

At the bottom of the poster, in my own shaky script, I wrote: Worthless.

Then I peeled it off.

Underneath, we revealed a second poster, pre-printed with: I Am…

They wrote again.

“Grandmother.”

“Veteran.”

“Teacher.”

“Friend.”

“Artist.”

“Still here.”

When the ink dried, we hung the posters in the senior center lobby next to the bulletin board advertising bingo and flu shots. People stopped to read them. To add their own.

One day, as I passed, I saw a new tag stuck there in a different hand.

It said: Survivor.

No name. No age.

I didn’t need to know whose it was.

I had my own.

Alice. Grandmother. Storyteller. Patron Saint of Second Chances. Woman Who Once Paid for Everything Except Her Own Self-Respect—and Then Changed the Terms.

I would have needed a very large name tag.

Part 5

The last big family celebration I attended was not a wedding, though there were flowers and bad dancing and people trying to keep their tears inside until they couldn’t.

It was my eighty-fifth birthday.

“You could have just taken me to dinner,” I told them when they shouted surprise in the back room of Chapter One. “This is excessive.”

“It’s not even enough,” Emma said, hugging me so tight my ribs protested. The bookstore was closed for the day, a hand-lettered sign on the door: Private Event — Come Back Tomorrow for Cake Crumbs.

The tables had been pushed aside to make a little clearing. Fairy lights drooped from the ceiling like the inside of a very tasteful jellyfish. On one wall, someone had pinned photos—black-and-white shots of Robert in uniform, Polaroids of a younger me holding baby Richard, a slightly blurred picture of Jennifer in her wedding dress with mascara streaks still visible, a glossy print of Michael and Emma on their wedding day under the reclaimed barnwood arch.

In the center was a photo I didn’t recognize: me, in my blue dress, laughing so hard my eyes were closed, holding Bobbie’s hand as we twirled under the Westbrook Hotel’s chandeliers.

“Who took that?” I asked.

“Me,” Richard said. “Snuck it between songs. It’s my favorite.”

He looked older now, like someone who’d fought his way free from a younger version of himself that didn’t fit anymore. He had remarried quietly—a woman named Ellen who taught high school English and refused to let him talk down to himself. Pamela had moved permanently to Florida and joined a club full of other women who liked complaining about alimony and “this generation.” I wished her well, from a distance.

My hip twinged when I sat, but it held. The walker had been replaced by a sleek cane with a fox carved into the handle—a gift from the senior center after I’d led my tenth boundary workshop.

They fed me too much. Played music too loud. Told stories.

“I remember when Grandma told off the fundraiser who assumed she’d be the top donor because she had white hair,” Cora said, now in college and home for the weekend. “She said, ‘I give where it matters, not where it looks good in a brochure.’ I have that on a Post-it over my desk.”

“I remember when you threatened to ground me at thirty,” Michael added, “if I signed a lease that put the store in debt over its eyebrows.”

“You absolutely would have deserved it,” I said.

Bobbie, now eleven and all limbs and opinions, rolled her eyes. “We get it,” she said. “Grandma is terrifying and amazing. Can we do cake now?”

We did cake. It had far too many candles, so the younger lungs helped. The frosting turned everyone’s teeth an unnatural shade of blue. No one cared.

After dessert, Michael tapped a glass with a fork.

“Okay,” he said. “We have a program.”

“Oh, no,” I groaned. “You scheduled this?”

“Of course,” he said. “You raised a family of planners and performers. This is your fault.”

The program had three parts.

First, Bobbie performed a dance she’d choreographed herself. It involved a lot of spins and a dramatic fall that she popped up from with a grin.

“It’s about resilience,” she explained, panting. “I call it ‘Get Back Up, You’re Not Done Yet.’”

“I feel personally attacked,” I told her, wiping at my eyes.

Second, Jennifer read a letter.

“Dear Grandma,” she began. “Do you remember the first time you babysat Bobbie overnight? She woke up at three a.m., screaming, and I called you in a panic. You said, ‘Babies do that. Grown-ups do, too. It’s just that nobody picks us up anymore.’ Then you drove over in your slippers and made us tea and didn’t leave until the sun came up. That was the night I realized love isn’t just money or weddings or big gestures. It’s showing up at three a.m. in your slippers.”

She sniffled. Mark handed her a tissue. “You’ve always shown up,” she continued. “Even when we didn’t deserve it. Especially then. Thank you for teaching us how to say no, which is really another way of teaching us how to say yes to the right things. Happy birthday. Please don’t die for at least another ten years.”

“Bossy,” I muttered, but my heart did a little flip at the thought.

Finally, Richard took the floor.

He held no notes. His hands shook.

“I’ve spent most of my life defining people by what they could do for me,” he said. “Status. Money. Opportunities. My mother was at the top of that list. I treated her like a resource instead of a person, because that’s how my father treated her, and his father before that. In my head, that was just how things were. It took losing almost everything—my inheritance, my marriage, my kids’ respect—to realize that ‘how things are’ is not a law of nature. It’s a choice. And we can make different ones.”

He looked at me. “You made different ones. You enforced the codicil. You stopped paying for everything and started insisting that we pay attention instead. You got called selfish for the first time in your life and decided you could live with that.”

A ripple of laughter.

“I want to say, in front of all these witnesses, that my mother is the bravest person I know,” he continued, voice thick. “Not because she survived, though that would be enough. But because she changed. At an age when every magazine and pundit likes to tell people to slow down, she sped up. She picked up new hobbies, new friends, new boundaries. She let some of us catch up. I am grateful every day that she gave me the chance.”

He swallowed hard. “Mom, I’m sorry for the years I made you feel like a walking ATM. I’m sorry you had to enforce a legal document to get my attention. I’m sorry for every joke I made at your expense. And I’m grateful you didn’t let that be the end of our story.”

He raised his glass. “To Alice. To my mother. To the old lady who used to pay for everything and now pays for the right things.”

They all echoed him.

I sat there in the middle of it, feeling like the eye of a hurricane made of love and regret and cake crumbs, and thought, This is what it means to rewrite your life: not erasing the bad pages, but writing so many good ones after that they stop making the first ones the whole story.

When the crowd had thinned and the younger ones had gone to do whatever younger people do after family parties—bars, movies, secret rooftop meetings—I found myself alone among the shelves.

The bookstore hummed with the quiet of after-hours. Dust motes danced in the slanting light from the street. Somewhere outside, a car door slammed. A dog barked. Life, unbothered by my milestone, went on.

Michael appeared from the back room, carrying a small box.

“Before you go,” he said. “One more thing.”

“I thought we’d exhausted you,” I replied.

“Never,” he said, handing me the box.

Inside was a frame. Behind the glass, on a cream background, was my original name tag.

Not the copy I’d thrown away in the park. The real one. The one from Jennifer’s wedding.

“The old lady who’s paying for everything. I’m glad to have you here.”

Below it, in smaller print, he’d mounted a second tag.

Alice — Patron Saint of Second Chances,

Grandmother, Storyteller, Investor in Better Endings.

I stared at it.

“You kept that?” I asked softly.

“I dug it out of your purse the day after the wedding,” he said. “I wanted to burn it. Then I thought… maybe one day we’d want to remember. Not the insult. The turning point.”

He pointed at the frame. “This is our before and after. I thought we could hang it in the back room. Staff-only. Like a relic.”

I laughed, a wet, undignified sound. “A relic?”

“Yeah,” he said. “A reminder. For when we get tempted to take each other for granted. For when I complain about the cost of printer ink and forget that once, this whole place was just a sketch on your dining room table.”

I ran my fingers along the frame.

“Put it up,” I said. “But slightly crooked. So it doesn’t look like it thinks too highly of itself.”

He grinned. “Your wish.”

He disappeared into the back, hammer tapping lightly a moment later. I sat, listening, breathing in the smell of old paper and new beginnings.

Later that night, at home, I climbed into bed more slowly than I used to. The house was quieter now—no little feet running down the hall, no Robert humming in the kitchen, no Pamela on the phone demanding explanations. Just the tick of the clock and the ache in my bones and the comfortable weight of my own company.

On my nightstand sat the same framed photograph that had been there the morning of Jennifer’s wedding: Robert in his tuxedo, laughing at something just out of frame.

“I did it, you know,” I told him. “I paid for everything that mattered. And I stopped paying for what didn’t.”

The room didn’t answer, exactly. But somewhere between my heartbeat and the creak of the house settling, I felt something like agreement.

I don’t know how many more birthdays I’ll have. I don’t know which of the grandkids will marry next, or what their name tags will say, or whether I’ll be there in person or just in the stories they tell each other when the music’s too loud and the cake is too sweet.

I do know this:

Once, I walked into a ballroom wearing a tag that told the world I was nothing but an open wallet. I walked out having decided that the world was wrong about me.

Everything since has been a long, complicated, beautiful receipt for that decision.

Signed,

Alice.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Karen B*CTH Tried to Stop CPR… She Never Saw the Consequences Coming!

Karen B*CTH Tried to Stop CPR… She Never Saw the Consequences Coming! Part 1 The first scream didn’t sound…

HOA Karen Invited 200 Guests to a Wedding in My Yard — I Flooded It With Dirty Water and Watched Her

HOA Karen Invited 200 Guests to a Wedding in My Yard — I Flooded It With Dirty Water and Watched…

HOA Karen Loses It When I Move Into My New Home That’s NOT in the HOA—Demands I Leave Immediately!

HOA Karen Loses It When I Move Into My New Home That’s NOT in the HOA—Demands I Leave Immediately! …

HOA Fined Me $2M — Then I Proved I Owned Their Entire Neighborhood!

HOA Fined Me $2M — Then I Proved I Owned Their Entire Neighborhood! Part 1 You never think your…

“She’s dead” My father said under oath. The death certificate? It had my name on it.

“She’s dead” My father said under oath. The death certificate? It had my name on it. They moved $6m into…

My stepson thought it was funny to tell his girlfriend I was “clingy” and “desperate for his approval.”

My stepson thought it was funny to tell his girlfriend I was “clingy” and “desperate for his approval.” So I…

End of content

No more pages to load