At My Engagement Mom Kicked Me In the Chest and Threw My Ring Into the Fire—She Laughed: “Dogs Don’t Become Brides”

Part One

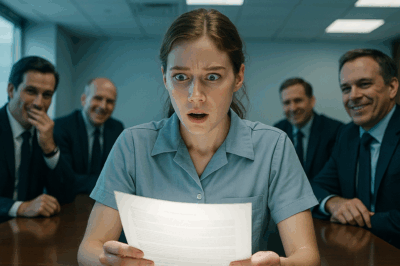

The music hadn’t even faded when my mother’s heel pivoted, her palm cracked against my sternum, and the world tilted. Air fled my lungs. My back scraped the polished floor. Somewhere in the thicket of gasps and silverware clatter, the word bride dissolved on my tongue.

Mom didn’t wait for my breath to return. She seized my left hand, twisted, and ripped my ring away—a ring Daniel had slid onto my finger not even twenty minutes earlier while everyone clapped and someone’s aunt dabbed her eyes with a napkin. She held it up like evidence, like something spoils a room, then hurled it into the fireplace. The gold winked once in the flame’s throat and was gone.

“Dogs don’t become brides,” she shrieked, her voice sharp enough to cut the bow off a cello.

Laughter spattered from the front table where my sister Kelsey sat with her friends, champagne flute in hand, eyelashes batting slow and lazy. “Guess Mom’s right,” she said, tilting her head toward the fire as if warming her hands over my humiliation. “Who would marry the family mutt?”

Daniel stood beside me half-extended like a buffering video: one hand raised, mouth open, eyes ping-ponging between me and my mother and the guests, calculating the distance between defense and disaster. His parents, near the back, looked horrified but stayed planted in their chairs, fingers pressed white over linen napkins. The band—poor things—kept their heads down and played something that pretended to be music.

“Pick yourself up,” Dad said mildly, as if instructing a dog, not a daughter. Then louder: “If you want to play bride, at least learn how to stay on your feet.”

I stood because I hated that he saw me on my knees. My ribs flamed where Mom’s kick had landed. The room’s heat had nothing to do with fire. It was the heat of eyes—neighbors, cousins, Daniel’s colleagues—studying me like a headline that hadn’t yet told them how to feel.

When I reached for Daniel’s hand, Mom slapped it away without even looking at him. “Don’t touch the mutt,” she said. “You’ll dirty yourself before the vows.”

I stared at Daniel—this man who had confessed secrets to me at two a.m., who had practiced saying my name in an empty kitchen like a prayer, whose palm had warmed my back in a crowded room as if to say, I see you. He swallowed hard and—God help him—lowered his gaze.

Something very old and very tired inside me stopped pleading.

Kelsey hopped off the riser, sashayed to the fireplace, bent at the waist, and sent a puff of air toward the embers where my ring had vanished. “Shame,” she said brightly. “The only shiny thing you ever had. Want me to buy you something from the dollar store? Maybe that suits a dog better.”

Polite laughter. A couple of pitying glances—pity’s just contempt that forgot to wear heels. An aunt whispered “Well, at least we know who the real daughter is,” her eyes sliding reverent and sticky to Kelsey as if ordained.

I tried to speak. Mom pushed me again. “Don’t whimper,” she said, smiling wide for the crowd. “Brides are supposed to be graceful. You? You’re something someone should have left outside.”

Dad lifted his glass as if to toast the end of a show. “Enough entertainment,” he said. “Sit down, mutt. The spectacle’s over.”

“No,” Mom said, pinching my forearm, nails sharp, her voice honeyed, carrying perfectly to the back of the room. “Not yet. Everyone here should know exactly what kind of joke this family almost let marry into theirs.”

She turned toward Daniel’s parents, and her sweet-venom smile widened. “Do you really want your son to marry trash? Because that’s all she is—trash with a dress.”

Daniel’s mother gasped softly, her lips parting like a curtain, but Daniel’s father—accountant-sober, legacy-cautious—placed a hand over hers. Don’t. In his world, storms pass if you pretend they’re weather.

The room blurred. The only thing in focus was the ceiling’s crown molding and the fire’s hiss. I could have run. That would have pleased them. They loved when I saved them the trouble of cleaning me up. Instead I smoothed my dress with shaking fingers, lifted my chin, and went silent.

The silence made them nervous.

“Cat got your tongue?” Mom taunted after a few beats, her jewel tones tightening. The silence held. Guests shifted. The band slid down the scale like a throat clearing. My stillness gathered weight.

I didn’t cry in a bathroom stall. I didn’t fling a glass. I didn’t scream. I stood there and memorized every face that didn’t move for me. I stared into the same fire that ate my ring, and I started planning.

People imagine plans are born in a single flash, but the good ones—sustainable, surgical, satisfying—are assembled with patience and a cheap notebook. The next morning, while the hall’s staff probably scraped wax off carpet and my mother told anyone who would listen that decorum had saved the evening, I sat at my small kitchen table and wrote everything down.

Not just last night. All of it.

The time Dad made me sleep on the back stairs for “backtalk” when I was twelve and Kelsey left a blanket at my feet and said, “Oops, forgot.” The time Mom hid my acceptance letter under the cereal boxes and then told the church she’d always feared I “wouldn’t be academic.” The checks written out of my savings “temporarily,” never returned. The way they rotated between silent treatment and slap whenever I looked like something independent.

The humiliation wasn’t the point of the list. The pattern was. Abusers love when you treat each of their acts like isolated weather. Patterns are climate. Climate gets funding.

When my hands stopped shaking, I started making calls.

The hall manager—her name was Bria and she’d once slid me a plate of hot rolls when she caught me hiding in a coat closet during a Christmas party—pick up on the first ring. “About last night,” she said delicately.

“I’m not calling to complain,” I said. “I’m calling to thank you for instructing your staff not to intervene when a girl’s mother wanted to audition for Cirque du Sociopath. Also: I know you have cameras.”

“We do,” she said. Then, because some women see what you’re building and hand you a hammer: “I’ll preserve the footage. If you need it.”

I did.

I called a lawyer—Mina—who had gotten a girl from my block out of a fake shoplifting confession when she was nineteen. Mina didn’t do family law anymore, but she did do strategy. “You can sue for assault,” she said. “But that’s whack-a-mole. You want leverage, not court dates.”

“I want change,” I said.

“Those aren’t the same thing,” she said dryly. “You need both.”

She taught me what to screenshot and when to shut up and how to email a bank.

Financial disclosure is the enemy of hypocrisy. My parents had tacked my adult life to their bulletin board like a receipt they thought they owned. They’d borrowed from my college fund; they’d encouraged relatives to “send cash to the household so it’s easier to cover the honeymoon deposit.” When I called the resort posing as Kelsey’s “assistant”—Kelsey’s favorite word for any woman she couldn’t name—my throat went tight when guest services cheerfully confirmed that the presidential suite had been prepaid from an account keyed to my old joint account with Mom.

I hadn’t closed it because closing things is an act of faith—a way of saying “I won’t be told I need this later.” Mina sat across from me during lunch and said, “You’re going to close it now.”

We did. We also filed a fraud complaint, a quiet little grenade with SPAM stamped on the outer shell. I didn’t want police at a party. I wanted accountability in writing.

I called a reporter named Larissa at the city paper and told her I wanted to talk about the gravitational pull of golden children and the disfiguring weight of family performance. “No names,” I said. “But specificity saves lives.” She knew my family; everybody with a Sunday bulletin did. She agreed to keep the angle general and the photos blurred. The important thing was the architecture.

While Larissa wrote, I stacked evidence into boxes. It’s not hard to find fakes if you live in a house that only buys mirrors. Awards Mom ordered online and presented to Kelsey at rented brunches; “scholarship” certificates with fonts you wouldn’t allow on a bake sale sign; letters Dad wrote “from the mayor” in which the mayor managed to spell his own name wrong.

When the stack was three boxes wide and one box tall, I called the hall. Kelsey’s birthday party would be there in three weeks. Of course it would. My mother had never met a room with a chandelier that she didn’t mistake for a friend.

“Let me borrow your stage for five minutes,” I told Bria. “If I go over, turn off the mic.”

“You’ll need a projector?” she asked.

“And a fire extinguisher,” I said.

Part Two

They screamed before I spoke.

I didn’t plan for that. I planned for applause, for gasps, for the kind of silence that follows a car crash. But the moment I pushed open the doors and stepped into the hall—black dress, hair clean, spine a straight line—the entire room tried to build a narrative around my face. Kelsey’s friends squealed like game show contestants. Mom’s mouth tightened, but she didn’t move; Dad cupped his drink like a gun.

“Look who crawled back,” Kelsey sang, perched on the edge of the stage in a dress that could have been used to signal ships. “Don’t tell me you’re here to ruin my night.”

“Sit,” I said to the room, and my voice carried in a way it never had when I begged.

They sat. Not all. Enough.

The men carrying boxes came in on cue. Security glanced at Bria. Bria nodded. The men stacked the boxes neatly by the footlights and took two steps back. Nobody laughed when I clapped once.

“Before you begin,” Mom said to me, bright and civil, venom in silk, “why don’t you congratulate your sister properly?”

“Because she’s not the reason I’m here,” I said, and slit the first box’s tape.

The frames inside were heavy. They had to be, to hold together so much glue. I held one up: Academic Excellence Award to Kelsey from a foundation that Larissa’s piece had already noted did not exist outside a Wix template and a P.O. Box registered to my mother’s name. The date at the bottom corresponded to a night I remembered vividly: the night Mom insisted we eat cake even though Kelsey was out with a boy and I had an exam the next morning. I’d taken notes between bites while Mom practiced smiling for the camera.

“Perfection has a receipt,” I said. “So does forgery.”

I didn’t throw; I placed the frame in the fire. Glass cracked. The room smelled like lacquered lies.

The next box had financial statements—transactions written out of my account and into Kelsey’s and our parents’. The clerks at the bank had printed them for me with a courtesy that felt like a blessing. I walked among the tables and set a page down in front of people who had borrowed my parents’ version of me when it suited them. “You said I lived off them,” I said evenly. “Turns out, they lived off me.”

Nobody touched the papers. For the first time in my life, I saw people recoil from my parents with something that wasn’t theater. It was distance. It was the sound a drawbridge makes when it chooses not to lower.

My father stood. He had a hand on his chest like a politician. “You think this proves anything?” he said, voice splintering. “You think you can humiliate us in public and—”

“Now you know how it feels,” I said.

He didn’t lunge. He sat, like a man who just remembered his ankles.

The last box was lighter. I took out a notebook, not the cheap notebook on my kitchen table but the expensive one I had found under Kelsey’s coat when she’d stormed out of my apartment days after the engagement, sick of me not apologizing. The cover was embossed. The pages were filled with a handwriting anyone at the front table would recognize from Kelsey’s Instagram captions. Pages about how exhausting Mom was, pages about how Dad was a joke, pages about how she would ditch them both the moment she had a brand deal that didn’t require a family.

It wasn’t the betrayal that mattered; it was the evidence that loyalty had never been the house currency. My parents’ faces fell in identical ways.

“You said dogs don’t become brides,” I said, flipping one last page for the room to watch the words bruise my mother. “Fine. We evolve.”

I tossed the notebook into the fire. The flames leapt. Kelsey’s hand flew to her mouth and stayed there, finally useful.

I could have stayed to watch the aftermath—the silent phone calls, the tight smiles, the way the room learned something it would not forget for a long time. Instead I turned to the exit and walked into air that didn’t need to be shared with anyone who confused cruelty with strength.

What happens after the fire is less photogenic. Lawyers wrote letters. Accounts got closed. Mom’s friends started saying “How terrible” with their voices and “Finally” with their eyes. Dad tried to sue me for defamation; Mina sent a fat binder filled with exhibits and a note that said “Truth is an absolute defense.” The suit evaporated like mist at noon.

Daniel texted. “I didn’t know what to do,” he wrote. “My dad… my mom… I froze.” He asked to meet. I asked him to write. He wrote three long messages that said “sorry” in increasingly ornate ways without ever saying “I should have moved.” I wrote back: You showed me something useful: the life I want doesn’t require your courage rehab. He didn’t reply. At some point, his mother called to say she was sorry “for the scene” and “for everything.” I said, very calmly, “We’re not engaged,” and hung up. I did not mention the ring. I didn’t owe that fire another word.

I moved apartments. I picked a place with a small balcony and a tree the landlord apologized for because it “makes a mess in spring.” I told him I wanted mess. I told him I wanted life that drops petals and doesn’t apologize for the sweep.

I found a job that used my brain and my backbone. People who had seen the video in the hall acted weird for a while. I let them. They would get used to me. Or they wouldn’t. Either way, I had finally gotten used to me.

On Sundays I made soup the way my grandmother had when she was tired: bones, onion, patience. On Mondays I answered emails with the kind of clarity that makes a person impossible to gaslight. On Tuesdays I went to a boxing class where women had bruises that weren’t metaphors and a coach who called me “kid” even though I wasn’t and said “keep your guard up” like a blessing.

The day an envelope came addressed in my father’s blocky, proud script, I opened it because sometimes closure comes disguised as stationery. Inside was a single line: I’m sorry. No excuse. No defense. No money order. I put the paper in a drawer labeled “documents,” not “memories,” and then I cleaned my bathroom, because control is sometimes a scrub brush and bleach.

Three months after the party, I stood in front of a mirror without a dress or a ring or a stage and looked at a woman with a scar along her cheekbone that only a trained eye would clock. I lifted a hand to my face and traced it, not as a wound but as a map. It led here. It would lead elsewhere. I smiled and believed what the curve of my mouth did to the room.

When people ask me what happened that night—and they still do, at parties, in kitchens, with napkins—they expect me to say “revenge” and they expect a laugh. I tell them it wasn’t revenge. It was a return. I returned everything my parents had handed me that didn’t belong to me—the shame, the script, the silence—and I set it down in front of them in the same room where they had dressed me in it. I watched them learn how heavy it was.

I don’t need them. I do not forgive them. I also do not carry them.

The last time I saw their house, a for sale sign tilted slightly in the rain. The yard that had once been Mom’s pride—edges like rulers, flowers like nouns—had gone shaggy. The porch light was burned out. They’ll find a smaller place, people said. They’ll reinvent. Maybe they will. People reinvent in smaller apartments all the time. I did. Reinvention without apology is an art.

This is how my story ends tonight, though it will go on tomorrow with laundry and a deadline and a basil plant that needs water: with me on my balcony, city air soft against my skin, the noise of other people’s dinners rising and falling behind me. I light three matches and blow them out. I do it not because I believe in magic, but because I believe in breath.

Dogs don’t become brides, my mother said.

She was right about half of it. I didn’t become hers. I didn’t become anyone’s. What I became is a woman who will never again be kicked out of a room that cannot contain her.

END!

News

To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him… CH2

To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him… …

“Mister, please take my little sister, she’s only six months old and very hungry.” Ethan turned and saw a 7-year-old boy holding a tiny baby close. ch2

The city’s pulse was a frantic drum against Ethan’s ribs. Time was a thief, and it was currently picking his pocket…

The Waitress Said, “My Mother Has the Same Ring.” — The Millionaire Looked at Her and Froze. ch2

Graham Thompson, the 53-year-old founder of Thompson Grand Hotels, sat alone at a corner window table in The Beacon, a warm, wood-paneled…

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… CH2

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… Part One…

My Son’s Family Left Me Stranded on the Highway — So I Sold Their House Without a Second Thought… ch2

Everything began about six months ago, when my son Ethan called me sobbing. “Mom, we’re in trouble,” he choked out,…

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract… CH2

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract……

End of content

No more pages to load