At My Birthday Lunch, My Daughter Whispered “While I Distract Him…” But She Forgot Who Built It.

Part I: The Restaurant on the Water

The restaurant sat on the edge of Lake Union, its glass walls catching the late afternoon sun like a handful of coins tossed across a blue table. I had always liked this place. Back when I walked jobsites with a roll of plans tucked under my arm and my hands smelling faintly of cedar and steel, I’d bring clients here to sign off on revisions. You could point out over the water, talk about span and load and view corridors, and pretend what you built would never age.

Today I was seventy-one, retired, still paying for my own cake. It made me smile in a way that didn’t reach the corners of my mouth.

My daughter Amelia had picked the spot. She said it had a good view for a birthday. She laughed quickly, the way people do when they want to sound happy. Her husband, Mark, scrolled his phone while pretending to listen. The waiter poured coffee, and behind him the lake glittered with the calm of a day that thought it had nothing left to prove.

We talked about their kids—my grandkids—how the soccer league kept changing fields, how camp registration opened at 6:00 a.m. and the website crashed. They mentioned a vacation they couldn’t afford and house repairs that kept moving from a plan into a corner where plans go to gather dust. I nodded and contributed what I could, letting the rhythm of their chatter wash over the tired places in me.

The waiter returned with dessert. Lemon butter clung to the air, and the tray held slices that were more sculpture than food. Just as he set it down, I heard it. A whisper. Quick, low, meant to slide beneath the music and the clink of silverware.

“While I distract him,” Amelia murmured, leaning toward Mark, “go change the locks.”

For a second my body did the strange, small thing it does when your brain insists you heard wrong. The hearing goes soft around the edges. The heart takes a step forward and then back like a cautious animal. I watched her eyes. She didn’t look at me directly. She watched me from the corner, timing. Mark’s thumb flicked the screen. He stood up and excused himself, said he had to make a call.

I wrapped my hand around the coffee cup and didn’t lift it. Heat gathered and slipped around my fingers, the way time does when you finally understand what it’s been trying to tell you. The room narrowed, not into a tunnel, but into a line. A plumb line dropping from the ceiling to the center of my chest.

“Dad,” Amelia said brightly, too brightly. “You know, you don’t have to rattle around that big house by yourself. Come stay with us for a while. It would be fun for the kids—Granddad in the guest room.” Her smile hinted at worry. “I just think about safety, you know? Stairs. Break-ins. Falls. People can’t live alone forever.”

I kept the small smile I used on impatient clients when they demanded I explain why you can’t remove a load-bearing wall unless you like waking up inside a tent. Inside, something heavy shifted into place.

The waiter returned with a cake: chocolate with raspberry between the layers and a clean white frosting that shone like plaster. The candles were already lit, numbers that looked like tiny warning lights glowing in the middle of a bright, crowded room.

“Happy birthday,” Amelia sang. Her voice trembled and she glanced at the door every few seconds. I joined in quietly. When an engineer says “quietly,” he means in a tone you could hang drywall on.

I let the song finish. I blew out the candles. We clapped a little. Mark still hadn’t returned.

About fifty minutes later, he came back through the glass door, his face pale, his tucked shirt sticking slightly to his chest. He sat and tried a smile that didn’t survive long enough to reach his eyes.

“Something went wrong,” he said. “Someone’s there. The papers are signed. The house is sold.”

The sound the room made then was not a sound at all, but the absence of one. The waiter cleared plates and apologized for interrupting nothing. Amelia stared at me, mouth slightly open, as if she’d discovered mid-sentence that she didn’t know the words.

I sipped my coffee. Steam fogged my glasses, and I let it. There’s dignity in small inconveniences when bigger ones have already been handled.

“Yes,” I said. “I sold it three weeks ago.”

I looked past them at the water. Calm as glass. I had built that house once. Now I was building peace.

When I first bought that land in Maple Valley, it had been nothing but wet earth and tall grass. The rain had just moved on, leaving the ground smelling like pine and promise and the stubbornness you need to make either one last. I was thirty-one, recently widowed, carrying a little girl who kept asking when her mother would come back from the hospital.

“Someday,” I told her, and the word burned in my mouth.

I worked for a construction firm then. Small contracts, remodels where the existing conditions had been hiding behind plaster for seventy years. I took extra shifts. I saved every scrap that looked like cash and every washer that looked like it could hold another twenty years. At night I spread used blueprints on the table and sketched my own house in the margins: a rectangle with a porch that faced the west; a living room with a wood stove because heat the eye can’t see is a poor substitute for heat it can; a bedroom with a window low enough for a child to discover constellations without climbing anything she shouldn’t.

The first boards I laid were rough and uneven and too proud of themselves. I planed them down. I blistered my hands and borrowed better tools and returned them on time because reputation is a currency you can spend only once. On good days, Amelia sat in the dirt with her dolls and pretended to be my supervisor.

“Blue walls,” she would announce, tiny finger in the air. “And a big window so I can see the stars.”

When I finished her room, she ran in barefoot and spun in circles until she collapsed, dizzy and laughing. That sound glued the whole place together better than any subfloor adhesive I’ve ever used.

We lived in that house through winters when the pipes froze and summers when the roof turned into a skillet. I’d come home from days that made my back feel like a complaint and my hands like a map, and she’d have set the table with macaroni or soup. I kept telling her that we didn’t have much, but we had enough. That’s all a person needs, I said. I thought she believed me. I think she did, once.

Time did what time does: turned fields into paved streets and coffee shops, turned my handmade house into a quaint reminder of a town people thought they made fresher by arriving. By the time Amelia finished college, the place was worth ten times what I paid for the land. She came home and told me I should refinance, upgrade, leverage.

I laughed. She didn’t.

She married Mark, a man who sold insurance and confidence in equal measure. I offered my blessing because that’s what fathers do when they are asked to approve what they can’t understand. They moved two towns over. They visited often. They brought the same combination of smiles and suggestions that make a man feel at once cared for and managed.

“The place looks old, Dad,” Amelia would say. “Let us help you. It’s too much.”

“It’s solid,” I’d reply. “What’s old is what’s lasted.”

Mark would look around like a man inspecting inventory. “You need a new roof. Better to do it now. Roofs don’t last forever.” He said it like I hadn’t spent forty years watching roofs behave exactly like people.

“Neither do fathers,” Amelia added once, softly.

The sentence hit a place my ribs had been protecting.

Months later, I noticed little changes in their visits. They took photos. They asked about my will. They asked about property values. Their eyes moved over corners where stories lived, too quickly to catch any. I kept a steady face and added details to a mental ledger. When a man has built something with his hands, he always knows what might break it. It’s the love. It’s always the love, once it decides to become something else.

On a rainy evening, I walked up their porch to return a toolbox. The window was open a crack. Inside, Amelia’s voice was low and tired but firm.

“He won’t live forever, Mark. We have to be smart.”

“Make it sound like it’s for his safety,” Mark answered. “You’re his daughter. He’ll believe you.”

I stood there and let the rain soak my jacket and listened to the last pieces fall into place. I did not feel angry, not in the way that boils and evaporates and leaves you raw. I felt something colder. Understanding. Love had become ownership. Concern had become strategy. The girl who once brought me lemonade in a chipped mug was planning which lever to pull and when.

That night, I sat at the kitchen table and unrolled the old blueprints. My wife’s handprint from a long-ago project smudged the margin. The key to the back door lay next to my coffee. I remembered beam weight in my palm. The first cut of the first board. The soft click when that door had turned for the first time and let us in.

Then I made a new plan. No more explaining load-bearing truths to people who wanted open concept. No more arguing with love that had decided to become control. It was time to protect what remained of me.

The next morning, at 8:15, I called a lawyer.

Part II: The House I Built, The Lines I Drew

Mr. Richards answered his own phone with a voice like newly planed poplar—smooth without being slippery. He was the same lawyer who’d handled a property line dispute for a neighbor, Mr. Patel, years back when a developer tried to jog a fence into land that wasn’t his.

“I need to make some changes,” I told him.

“Come in,” he said. “Bring whatever you have and whatever you remember.”

I brought both, and I brought a list.

We drew up a will that could take a punch. We drew up durable power of attorney and medical directives. We created accounts with controls and oversight. I authorized him to hire a geriatric psychologist to evaluate my cognitive state, the kind of exam that asks you to remember three words and then tries to unseat them with arithmetic and distraction. I remembered the words. They were ordinary—apple, nickel, chair—but I carried them like a chord progression for the rest of the day anyway.

“People file guardianships because they love you,” Richards told me, “or because they want you. The documents help with both.”

The sale itself was less romantic than moving day and more complicated than most marriages. I interviewed buyers. I didn’t list the property the usual way. A young couple with a baby on the way wanted to tear it down and “start fresh.” A tech investor wanted to hold it and “maximize.” An architect named Lena came on a rainy Saturday with a sketchbook and a look that let me breathe.

“I’ll restore what you made,” she said simply. “Not like a museum. Like a living thing.”

We talked about vapor barriers and the way the floor settled. She knew how to listen to a building, which is rarer than money. I sold the house to her for less than the highest offer and more than I expected, paid in cash at closing with all the necessary signatures and stamps and notarizations that transform a home into a stack of papers you sign while trying not to shake. I kept a drawer of artifacts: a brass cabinet pull, the first broken level I ever owned, a photo of Amelia at six standing in the doorway with a popsicle stain on her shirt and sawdust in her hair.

I moved into an apartment overlooking the same lake where my birthday had happened. Small. Two rooms and a kitchen that didn’t try to be more than it was. The windows were wide. The morning light came exactly where I wanted it. In the corner, I kept two canvases I’d been threatening to paint for twenty years and never had. Against the wall, I stacked a few planks of cherry and maple and poplar, short lengths people give away because they don’t know that small pieces often make the best things.

I informed Amelia and Mark of the sale the way you inform people of a fact they won’t like—clearly, once, on paper. I gave them Mr. Richards’s information. I invited them to ask him questions. I did not invite them to move my decision.

Days slid into a pattern that felt like weather I’d ordered for myself. Coffee at 7:30. A walk by the water if it wasn’t pouring, and sometimes if it was. A bus ride to the community center in the afternoon, where I started showing up in the woodshop as a volunteer. The first day I watched a kid named Jonah drive a screw near a board edge and blow out the grain. He winced like he’d done something unforgivable.

“Two inches,” I said gently, tapping my finger along the board. “Give the wood room to be what it is. Materials have needs. People do too.”

His next screw held.

On Thursdays, I had lunch with Mr. Patel, who’d become a friend without either of us naming it until one day he described a new grandchild using more adjectives than I knew he had, and I found myself describing the feeling of sanding a tabletop until it reflects breath. We ate at a diner that smelled like coffee and honest work. He told me how his arthritis made the buttons on his shirt a test he didn’t always pass. I told him about Amelia.

“She is not your enemy,” he said into his soup. “But she is not your friend right now either.”

The call from Mr. Richards came two weeks after the birthday lunch. “They’ve petitioned for temporary guardianship,” he said. “Cites irrational financial decisions, isolation, and concern for your wellbeing.”

“I expected it,” I told him.

“We’ll answer,” he said. “Calmly. You’ve already done the hard part.”

When we met to prepare, he set a stack of documents on the table so neat any inspector would have nodded. The property sale, the bank statements, the evaluation, the letter of instruction I’d written myself in my own hand—why I sold, why I set up the accounts, whom to call if I died, who got which tools and why. I kept the tone like a spec sheet and the sentences like stud spacing. You can feel when a wall is solid. You can feel when a story is, too.

The day before the hearing, I stood by the lake and watched a woman row. She had the economy of movement people spend lives chasing: no wasted stroke, no splash, no drama. She just went where she meant to go. I took that image with me to bed and I slept.

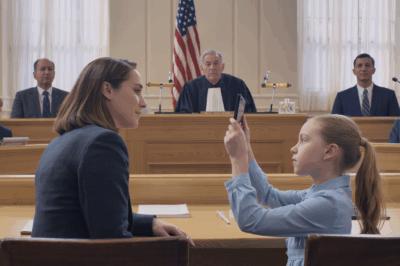

The King County Courthouse is a beige building that smells like old paper and stronger coffee than you get anywhere else. The courtroom was smaller than I expected. Cold. On their side, Amelia and Mark sat with a lawyer who had a voice like marble: polished, expensive, colder than reality. On mine, Mr. Richards sat with a pen he never clicked and a face that had learned long ago not to perform.

The opposing lawyer spoke first. He talked about mental decline and impulsivity. He painted my independence as isolation. He called the sale “rash.” He used the word “exploitation,” which I filed in a drawer tagged Projection. His sentences sounded like laminated pamphlets.

Mr. Richards stood, adjusted his glasses, and put one page at a time into the judge’s hands. Signed deed. Notarized affidavits. Bank statements with balances that wouldn’t strain a man who lives small. The evaluation, whose pages smelled faintly of the doctor’s peppermint gum. He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t sharpen it either. He let each word land and stop, the way you set a beam down and, if it holds, you don’t test it with a dance.

The judge asked if I wanted to speak. I stood. My knees did what old knees do when asked to carry what ego no longer needs. I told him I sold my home because I learned my daughter and her husband planned to take control of my property through a legal mechanism I respect in principle and feared in practice. I said I had proof—text messages, an overheard conversation. I said I had counsel. I said I had acted with deliberation, not panic.

While I spoke, Amelia looked at me, tears pinned in the corners of her eyes like someone had hung them there for later. For a moment—one exact moment—I saw her at six, barefoot in sawdust asking about the stars. I softened, which is to say I remembered. Then she leaned toward her lawyer and whispered with intent, and the moment put its shoes back on and left.

The judge read. He turned pages that had the weight of what a life looks like when you contain it in paper. He looked at me for a long second, the way men look at bridges and try to imagine where the stress travels. Then he spoke.

“No evidence of mental incapacity,” he said. “No evidence of mismanagement of funds. No legal basis to remove this man’s autonomy.”

He denied the petition in full.

The gavel touched wood once. I felt no victory, exactly. What I felt was stillness, like the quiet after a storm when the air has been scrubbed and the ground is honest about its puddles.

Outside, the sky had the color of work socks and the air felt light. On the steps, Amelia called my name. Her voice trembled between anger and shame.

“It didn’t have to be like this,” she said.

“It didn’t,” I agreed softly. “Love without respect becomes control. One day you’ll understand that.”

I walked away. My feet knew where I was going. I had already built it.

Part III: After the House, Before the Letter

Life is not a series of dramatic speeches. Mostly, it’s coffee filters and light bulbs and deciding when to buy lemons and when to buy limes. My new apartment made these decisions easier by limiting options. Problems become friendlier when they get smaller.

I learned how the light moved across my walls. It paused at the kitchen counter at 9:10 like a visitor who never stays long; it stretched across the floor at four like a cat. I hung a photo of my wife on the wall by the table. She’s twenty-four in it and looking past the camera at a punchline I didn’t catch. I say good morning to that smile and let the rest of the day become what it wants.

I went to the community center three afternoons a week. The woodshop had the kind of controlled chaos that tells you people are actually making things: clamps hanging like bats; sandpaper in grits no one respects until they need them; a bin labeled Offcuts that proves waste is a failure of imagination. I showed kids—and grown-ups who had been told they were bad at making—how to square a board, how to read grain. They showed me how much wonder I had that wasn’t gone, just buried under concrete.

There was a woman in her thirties named Teresa who wanted to learn how to build a bookshelf because her son had outgrown plastic crates. There was a high school senior named Luis whose hands learned as they moved and whose eyes did too, if you looked close when he sanded. There was a retiree from the post office named Harriet who told me she had walked twenty thousand miles in her career and now wanted to build something that would stay put.

“If you can measure your life in miles,” I told her, “you’ve already done something true.”

I taught them the joint that thrilled me when I was twenty and still does: mortise and tenon. The first time two pieces joined and refused to come apart without complaint, the room clapped. It embarrassed them, and then it didn’t.

On Sundays, I walked the lake. The boats lifted and settled. Couples took photos and pretended to be candid. Running clubs moved past like small flocks, feet soft and synchronized. I learned the names of dogs I would never own and the names of plants I would always recognize and never identify.

The house crept back into my thoughts in small, careful ways. Not the courtroom, not the whisper, but the kitchen when the light fell across the table and found the groove my knife had carved thirty years ago, the porch when the first snow made everything quiet enough to feel like a new city. I imagined Lena, the architect, sandpaper in hand, working the top of the newel post until her palm land and the wood rose up to meet it.

Sometimes I pictured Amelia standing at the gate, looking in at a home that belonged to someone else and thinking you can’t steal what you didn’t build. I never stayed with the picture long. The mind will make you cruel if you let it. I will not let it.

They tried once more, by phone. Mark called with concern dressed as expertise. He told me my accounts weren’t secure. He told me about a friend who had lost everything in a fraud. He told me they could take over my “financial life” just to make sure.

“Son,” I said, and the word was not affectionate, “I’ve used the same kind of tape measure for fifty years. I know how far six feet is without looking. I know when the number’s wrong. You take care of your home. I’ll take care of mine.”

He hung up politely. I set the phone down and went to sharpen a chisel. There are better sounds, but not many.

The final accounting from the sale cleared. Mr. Richards called to say we were finished. His voice carried the relief of a man who supervises worry as a profession. I thanked him. I sent a small gift—an old folding ruler I’d found at a flea market, polished and working. He wrote a note back that read like a blueprint for gratitude.

“Come by if you ever feel unsteady,” it said. “We’ll check your level.”

I started painting in the evenings. Nothing to sell. Things I’d carried in my head and didn’t want to anymore: the way snow gathers on cedar, the way a truss looks in silhouette, how light falls through scaffolding as if it were something you could carry out in a bucket. I wasn’t good. I was honest. It was enough.

Mr. Patel’s daughter visited from Portland with a baby who smelled like warm bread. She asked me if I missed the house. I told her I missed what it let me become. “That’s different than walls,” I said. She nodded, because young people with babies are kinder than we deserve.

One afternoon, I checked my mailbox and found a white envelope with my name in a hand I’d recognize anywhere. Amelia’s handwriting had always hesitated at the top of curves, then committed. She’d addressed it without flourish. No hearts over i’s. No extra loops. Just my name and an apartment number that still felt borrowed.

I took it upstairs and set it on the table with the corners aligned to the wood. I made tea. I opened it.

She apologized. She did not beg. She described fear the way you describe weather you drove through even when you knew you should have pulled over: pressure from bills; a husband who liked the idea of leverage as much as he liked breakfast; friends who talk about inheritance as if it were a college fund waiting for permission. She said “I lost sight.” She said “I forgot who built it.” She said she didn’t want money. She wanted forgiveness. She wanted to know if I would ever meet her at the lake again.

Her words were shaky and honest enough. The hard thing about being seventy-one and still able to lift what you need is that you can tell when wood is green and when it’s merely wet. I believed her. But belief isn’t a password. It’s a door you open only once you’ve checked the hinges.

I took out an old photo. It was one I’d kept in a drawer and not on a wall because I couldn’t stand to look at it and couldn’t stand not to. The doorway of the house, the jamb where I’d marked her height in pencil every year. The first notch low and smudged. The later ones straighter, surer. I thought I’d given the wood to Lena when we pulled the trim. Turns out I’d taken a picture to cheat the ache.

On the back of the photo, I wrote: “You can rebuild, Amelia. Start with your word and with the kids.”

I mailed it that evening. I walked past the lake and kept walking, the water turning gold for no one in particular, which is the best way.

Part IV: What Stays, What Leaves

Summer flexed and crackled. The community center added a class for teenagers who thought they hated tools because no one had shown them the difference between a hammer and an opinion. Jonah returned every day and taught another kid how to seat a screw without splitting the board.

“You told me once tools have needs,” he said, proud he’d remembered a sentence an old man had assigned him. “People do too.”

I grinned. “That they do.”

We built a picnic table and donated it to the park. We built three shelves that sagged until we rebuilt them with a middle support and learned that strength is often a problem of geometry and humility. We made a small bench for a woman who hadn’t asked and a larger one for a man who wouldn’t. Both cried.

I brought a box of offcuts to the class and told them to make anything they wanted as long as it didn’t require nails or screws. The room filled with tiny jointed animals, abstract sculptures, and one perfect little stool Harriet made for her granddaughter so she could reach the sink. If you think craft is a small thing, you have not watched a child wash her hands proudly on a stool someone who loved her built.

I heard rumors of the house now and then through the neighborhood vine. Lena had stripped the kitchen cabinets and saved what could be saved. She kept the wood stove and found a way to line the flue so it would behave better in January. She cut a window in the back room that made the yard look like a painting. She invited neighbors to see. She didn’t invite me. I was grateful.

On a Wednesday, the doorbell rang and I opened it to find my granddaughter Lily holding a stack of books and a shy smile. She’s nine and built like a spring. Amelia stood behind her, hands folded, an expression that has the dignity to be uncertain.

“We were at the farmer’s market,” she said. “The kids wanted to see the boats.”

I stepped aside. “Then they should.”

Lily ran to the window and narrated the water: a kayak, a ferry, a floatplane cutting a V into everything and taking off like a secret you’re allowed to watch.

Amelia stayed by the door. “I got your photo,” she said. “I have it on my dresser. I read the back every morning.”

“Good,” I said, and meant it.

We didn’t talk about court. We didn’t talk about the birthday lunch. We made small talk and it was not a small thing. I poured lemonade. Lily placed a sticker on my shirt that read HELLO, I’M AWESOME. I left it there because some truths deserve to be ridiculous.

Before they left, Amelia asked if she could come by again. She didn’t say when. She didn’t lock me into her calendar. That was her first rebuild: a question instead of a plan.

“Bring the kids,” I said. “Bring nothing else.”

They came on Saturdays sometimes. We walked by the water. I told the children about how bridges hide their beauty in utility, how the best ones are the least photogenic up close. We watched a man play a violin badly and another play it well. We ate ice cream. They wore half of it home.

Amelia and I built a new language, plank by plank. She apologized once more—not dramatically, not as a scene. She apologized in the way people apologize when they finally believe themselves. She said she had left Mark. It wasn’t my business and she didn’t make it my fault. She said she took a job at the school library. She said she liked the sound of pages and kids. I told her there are worse sounds.

We stood at a crosswalk and watched a cyclist who should have known better thread the needle. She laughed by accident, and for a second I saw her at six again. I let the second last.

“What happened to the house?” she asked once, months later, voice careful.

“It’s in good hands,” I said. “Not mine. Not yours. The right kind.”

She nodded. She didn’t ask for the address. That was her second rebuild: understanding the difference between curiosity and claim.

I kept the rest of my life plain because plain is a kind of luxury too. A neighbor, Mrs. Alvarez, asked if I could take a look at her back steps. I did. We replaced a stringer and a few treads. She tried to pay me in cash. I took a jar of peach preserves instead and decided that was the best exchange rate I’d ever gotten.

Mr. Patel’s arthritis won a few mornings. I taught him the shirt trick: sit, pull your arms in, find the buttonholes with your thumbs first, then the buttons. He told me he felt foolish. I told him that foolishness is just pride with its shoes on the wrong feet.

Harriet’s granddaughter brought the little stool into the shop to show me where she had drawn flowers on it. “Decoration,” she announced. “Functional art,” I replied, and she nodded like we had just agreed on a treaty.

On the anniversary of my wife’s death, I made two cups of coffee and set one by her photo. I told her I had finally engineered my life to fit. She would have rolled her eyes at the pun. She would have kissed me on the cheek anyway. I sat a while and let the day be heavier than the others. I’ve learned not to persuade grief to change its plans.

Near evening, an email arrived from Lena. The subject line had the house address. The body was one sentence and a photo: She is steady and loved. In the photo, the kitchen table shone. The stove looked proud. The doorway in the background had new trim, but it wore the light the same way.

“Good,” I wrote back. “Then we did it right.”

Part V: The Peace I Built

Fall sharpened the air. The water traded summer’s sparkle for a color I’ve always liked better—blue with weight in it. I started bringing a thermos on my walks. I started wearing a jacket that knew how to be old.

The community center asked me to teach a night class for beginners. I agreed on two conditions: no power tools for the first three sessions and music low enough to hear each other. We began with a box: six pieces, four walls, a bottom, a lid. Everybody laughed at how humble it was. Then they cut a little and laughed less. On week four, when the lids fit and the corners didn’t gap, the room exhaled together. I wrote a sentence on the whiteboard and pretended I had gotten it from somewhere else: Understanding is the joinery of the mind.

One evening, I ran into Mark outside the grocery store. He carried a basket and the kind of face you get when you realize the long road is longer than you thought. We exchanged nods a man uses when he doesn’t want to re-open weather he survived. He said he hoped I was well. I said I was. He didn’t apologize. I didn’t invite him to. Not every lesson needs to be spoken to be learned. He passed me in the aisle where they sell tape and light bulbs and dog biscuits. I bought what I needed. He bought what he did. We went home.

That night, Amelia called. “I found a small apartment,” she said. “The kids are excited about the bunk bed. I’m sorry it took so long.”

“You took exactly as long as it takes,” I said.

We invited them to the community center’s holiday event. The woodshop set up a table with small things the kids had made: candleholders with perfectly imperfect chamfers, picture frames, a single cutting board Luis had flattened within a whisper of true. Lily chose a tiny box stamped with her initials. Jonah taught her how to oil it. Teresa’s shelf made a father cry, then stand straighter. There are rooms where pride treats itself like a guest. This was not one of them. It lived here.

Toward the end of the evening, the director asked if I’d say a few words. I don’t like microphones. They make me sound like a warning. I spoke without it. I told the room what wood had taught me. How it doesn’t forget. How if you fight it, it cracks; if you listen, it carries. How strength isn’t always about thickness. Sometimes it’s about grain direction and where you place the load.

I didn’t mention birthdays or whispers or courts. I didn’t need to. The people in that room knew about load.

When the night ended and the lights came up, I locked the shop and stood a moment in the smell that has followed me for half a century. If you could bottle it—oak and glue and ambition—you could sell it to people who’ve never built anything and make them feel like they had.

Back home, I made tea and opened the window a crack. The city breathed. Boats clicked in their slips. Somewhere, someone played guitar poorly, and it was beautiful because it was theirs. On the table lay another letter from Amelia. The envelope had been opened and closed twice. She wanted to meet the next morning, at the lake, by the bench that looks at the little island where seagulls run their little governments.

We met in coats and careful smiles. She told me she’d been going to counseling. She told me she was learning how fear dresses up like love when it wants to be forgiven in advance.

“I wanted safety,” she said. “I tried to buy it with control.”

“You can’t,” I said gently. “You can only rent it with trust.”

She laughed a little then cried a little, and neither of us apologized for either. Lily and her brother, Max, ran in circles and came back with leaves and opinions. Amelia asked if she could come by the community center and learn a joint.

“Start with a box,” I said. “Everyone does.”

When she came to class, I paired her with Harriet. They measured twice. They cut once anyway and learned. The lid fit on the second try, and Amelia looked at me with a pride that didn’t ask for approval, only witness. She gave the box to Lily, who put a note inside that said simply: secrets.

Later, I sat at my table and wrote a letter to my wife. I told her about our daughter, about the moment the bridge we didn’t know we were building finally held. I told her I had stopped fighting for things and started standing for peace. Dignity, I wrote and underlined without shame, is the only thing that does not crumble with time.

There are days when memory still ambushes me. The bright white of the hospital. Amelia at three asking a question the world refuses to answer kindly. The house at Maple Valley echoing after I took the last box out and turned to look one more time. The restaurant on the lake where a whisper changed its clothes and pretended to be a plan. But then there are other days—the ordinary kind—when I adjust a clamp or mend a neighbor’s step or watch a kid see grain for the first time, and I think this is the better story.

Tonight, the lake took the sun like a prize and flattened it into gold. I walked along the shore and watched light climb the buildings and then slide off into the water without complaint. I didn’t think about what I’d lost. I thought about what I kept: my word, my work, the steady quiet that comes when you place weight exactly where it belongs and nothing sags.

I built a house once. I built a life. When someone tried to turn love into ownership, I built a different kind of strength. Not walls. Boundaries. Not locks. Decisions.

The water went dark in that soft way Seattle manages without asking permission. Somewhere across the lake, a window lit up, then another, and then a hundred more, reminding me that every room holds a story that isn’t mine to tell. I took a breath that went all the way down.

True peace, I thought, comes when you stop fighting for things and start standing for peace. So I kept walking, and the light faded, and the city breathed, and the work waited for tomorrow—steady as ever, exactly where I left it.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

MY PARENTS SUED TO EVICT ME SO MY SISTER COULD OWN HER “FIRST HOME.” IN COURT, MY 7-YEAR-OLD ASKED

My parents sued to evict me so my sister could own her “First home.” In court, my 7-year-old asked the…

My Sister Fired Me from Our Family Foundation Then Smirked as Our Parents Called It “Fair”…

My Sister Fired Me from Our Family Foundation Then Smirked as Our Parents Called It “Fair”… Part I —…

I Found Out My Parents Gave Our Workshop Business To My Younger Brother So I Stopped Working 80…

I Found Out My Parents Gave Our Workshop Business To My Younger Brother So I Stopped Working 80… Part…

What happened to your child that made you realize nuclear was the only option?

What happened to your child that made you realize nuclear was the only option? Part I: Static Before the…

She Was Just Cleaning the Range — Until Enemy Attack Began and a SEAL Handed Her His Sniper Rifle

She Was Just Cleaning the Range — Until Enemy Attack Began and a SEAL Handed Her His Sniper Rifle …

They Mocked Her at the Gun Range — Then She Revealed She has…

They Mocked Her at the Gun Range — Then She Revealed She has… She was just a quiet nurse at…

End of content

No more pages to load