At Midnight, My Stepfather Beat Me—My SOS Text Brought the Special Forces to My Rescue

Part One

I woke up in the military hospital to the rhythm of machines—soft, insistent beeps that announced I was still on the right side of a line someone else had tried to push me over. My left shoulder was bound into a compact geometry of bandages, the dull ache of a dislocation pulsing with each breath. My cheekbone throbbed in time with my heartbeat. The pain was background noise though, a radio in another room. The loud thing—the thing so loud I couldn’t look at it straight on—was a single image branded behind my eyes: my mother framed in my apartment doorway, hands limp at her sides, mouth parted, watching while my stepfather’s hands closed on my neck.

I am Sergeant Maria Mills, United States Army, Special Forces. That night, the army part was an afterthought. I was just a daughter whose past had broken into her present like a storm takes down a fence.

It started long before midnight.

Back in Los Angeles, when life still wore the smell of coconut surf wax and fresh-cut grass, my father used to wake me at dawn on Saturdays. The Ford Ranger’s cracked dashboard was always warm by the time we reached Santa Monica, even before the sun climbed above the water. He’d tap the windshield where the set was forming and say, “Look. Lines. You face them. Don’t turn your back on the ocean, kiddo. You’ll learn to read it or it’ll roll you.”

He spoke like an engineer and a poet at once, and at twelve I believed you could hold both kinds of magic at the same time.

The day the highway patrol knocked, the world didn’t end so much as drain of color. Two officers in rain-dark uniforms, their faces locked into professional grief, told us a semi had jackknifed in the storm on the 405, and my father had been in its way. My mother made a sound you don’t hear unless you’ve been there. It was a howl without air in it.

After the funeral, she went to bed and forgot how to get up. The house made new sounds—plastic casserole lids opening and closing, the thud of bills stamped PAST DUE on the hall table. The air shifted from coffee and lemon cleaner to lilies and dust. I learned how to read an instruction manual for a washing machine and how to walk like my feet didn’t touch the floor so I wouldn’t wake the grief.

Two years later, a neighbor sent a contractor named Corbin to deal with the leak in the roof. He filled the doorway—broad shoulders, confident grin—and he brought the noise of living back with him: the thunk of a hammer, a saw’s song, the rumble of a truck. He fixed the faucet without charging, brought groceries in paper bags he set on the counter with a flourish. He made my mother laugh at jokes I wouldn’t have found funny even then.

He was careful with it. We were starving, and he fed us what he knew we’d swallow.

The night he gave me a necklace—a delicate strand of silver that shone in the light from the kitchen—he clasped it around my neck and leaned close, so close his breath warmed the fine hairs near my ear. “Your dad’s gone,” he whispered, the words tidied up for anyone else’s ears but me. “I take care of you now, as long as you know your place.”

I was fourteen and had just learned what a collar felt like.

He didn’t hit me then. He didn’t have to. He wrote rules into the air and made my mother recite them back without words. Doors stay open. Numbers are accounted for. Dreams are impractical. Your place is not yours.

He made it look like care. People like him get good at that.

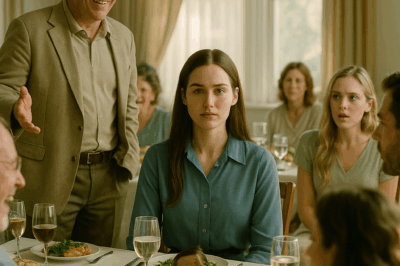

By the time I was seventeen, a teacher slipped me a glimpse of oxygen. I wrote an essay about the ocean and the father who had taught me how to survive it, and a district-wide literary award arrived in a manila envelope with my name spelled correctly. I carried it home like a passport. Corbin was at the kitchen table with a beer and his composition notebook—the ledger where he tracked my hours from the coffee shop like inventory.

“Let me see that,” he said, and his eyes skimmed the page. “Literature?” He snorted. “What are you going to do with this—write greeting cards?” He dropped the certificate on the counter like a napkin and turned to my mother. “This is your fault. Filling her head with useless, artsy nonsense.”

That was my cue. It always had been. I looked to my mother to do what mothers do in the stories people tell about family, to push back. She wouldn’t meet my eyes.

“Just put it away,” she said.

That night, the television murmured in the living room, and Oprah’s voice said, as if in answer, Turn your wounds into wisdom. I stood in my mother’s doorway and asked the question you ask when you’re drowning and the lifeguard has her back turned, called her name like it might wake us both. “Why do you let him do this to us?”

For once she didn’t pretend. “I’m scared,” she said. “I’m terrified of being alone. I can’t provide for you the way he can. At least he’s here.” She took my hand, her fingers cold. “You’re stronger than me. Don’t you let him break you like he broke me. Go. Save yourself.”

I signed the enlistment papers four months later in a sterile office at the Van Nuys recruiting station that smelled like stale coffee and industrial cleaner. Sergeant Miller—carved-granite face, kind eyes—laid out options like maps. I picked the hardest one, the one that matched the way my muscles had learned to hold fear and anger like weights. “This path will try to break you,” he said.

“I know,” I said, and meant it in a way fifteen-year-old me couldn’t have.

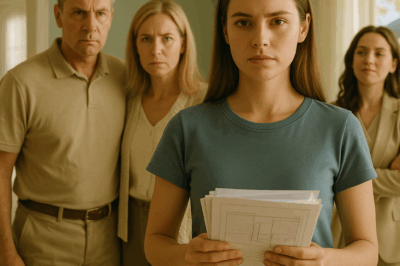

I needed my mother’s signature. She read the papers slowly, carefully, the pen hovering. Fear sat next to love and mustered. Her hand shook but didn’t pause. She put blue ink into the future and slid the form back to me like a key.

I told Corbin at dinner, not to ask but to inform. He flipped the chair. He told me I was his. He called me ungrateful. He told me I’d run out of the house with nothing and return with nothing again. I looked at him like I had learned to look at waves. Tall, yes. Loud, yes. Deadly if you turn your back on them. “You don’t own me,” I said. “And this isn’t your house. It was paid for with my father’s life.”

He raised his hand. I didn’t flinch.

I left with a duffel and a photograph of my father in his navy dress uniform. My mother hugged me on the porch and didn’t cry so I didn’t. She pressed a crumpled envelope into my hand—two hundred dollars saved a dollar at a time. “Be strong,” she said, and it wasn’t encouragement. It was a strategy.

Fort Bragg peeled my old life off me like a bandage. They broke us early and often—in the rain and in the heat and in the mud—and then trained our bodies to knit back together smarter. It was cruelty with a curriculum, and it was a relief. This pain was chosen. This pain had an end.

I found my squad in a land navigation course in Uwharrie National Forest after twelve miles under a sixty-pound ruck. I slipped on a slick rock and felt my ankle argue with physics; the ground came up like a fist. The training manual says teammates look after their own objectives first, but Sloan—lean, West Texas tough, all silence and competence—slid to her knees in the mud, fashioned a splint with two sticks, hefted my ruck onto her own shoulders alongside hers, and said, “Get up, L.A. We leave no one behind.”

I learned command voices have registers you can’t fake. Captain Eva Rostova had gray eyes and algae-cool composure; she clapped exactly twice in my presence, once at our graduation and once after a live-fire exercise when a private who thought rules were suggestions learned otherwise. At my evaluation, she closed my file and said, “Your record suggests you ran from something. Runners don’t make it here. Fighters do.” She didn’t smile; she didn’t need to. “Welcome to the team.”

I built a life on the West Coast near the ocean that had taught me the first rules of survival. The on-base apartment was beige and issued and therefore exactly right. The first time I stood in a grocery store and bought the cereal I wanted because I could, alone, felt like extravagant rebellion.

Every month, I called home and tried to talk to my mother around a silence that didn’t leave the room. Corbin’s voice rose in the background sometimes—queries made to sound like statements, “Who’s that?” and “Get off the phone, it’s costing money.” The Christmas card showed my mother in front of a tree with a smile that had too much white showing, her hair pulled to one side, concealing nothing at her temple if you knew what you were looking for. I called. “I fell,” she said.

“On the stairs,” I repeated, and didn’t say liar out loud. It hammered against my molars anyway.

“I’m coming home,” I told her. “No,” she said, panic suddenly present in her voice, desperate and childlike. He grabbed the phone, and he said a thing that belonged far less to kitchens than to alleys. “What’s she going to do? Call the cops?” He laughed, and he hung up.

I didn’t sleep. When I told Captain Rostova I needed leave, I didn’t cry, and she didn’t embrace me; she simply said, “We’ll document everything, Sergeant. Keep your head on a swivel.”

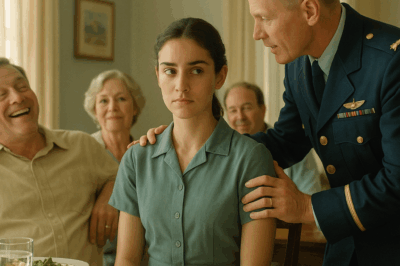

The house hadn’t changed in a way that mattered. It sat where it had. The buganvilia had taken the fence the way cruelty takes the spine first. My mother opened the door with the quick hug of someone who is being watched. Corbin filled the hallway behind her, wiped his hands on his jeans as if washing them. He had erased my father from the living room shelves, replacing photographs with photographs of himself—one hand on the antlers of a dead buck, another gripping a wild boar by the jaw.

He did not let us sit alone. He did not let us be alone. He watched. When he left the room, I slid a hotline card into my mother’s palm, and she looked at it as if it might explode. “I don’t need that,” she said, the lie so obvious it was already bruising. He returned and frowned theatrically at our whispering.

“I finished the new fence,” she said on the phone later, her voice flat. “It’s very tall.” It wasn’t information. It was a sermon.

When I left, he stood in the entryway and made a promise with his voice. “You can run,” he said, “but you can’t hide. I know where you are. I know where you work.” He wasn’t guessing. He wasn’t threatening. He was reporting.

I returned to base and built a perimeter around my peace. I checked the deadbolt twice and then three times. A blocked number called, and I listened to the silence until the silence bloomed into a radio in the background and then into Garth Brooks singing about friends in low places, and I was on a kitchen patio in the valley twenty years earlier watching my mother laugh like she didn’t know how to cry yet. I found a cigarette butt crushed under the window to my bedroom and my body remembered how to be fourteen, how to listen for footfalls down the hall.

Sloan watched me reload a magazine with hands that shook like I held winter. “He’s in your head,” she said simply. “That’s his battlefield. Don’t let him keep it.” I nodded like a recruit and tried to shut the door in my mind he kept opening.

The storm that night had the same fervor as certain arguments; it wanted to prove something to the roof. The knock, when it came, was polite. Everything after wasn’t. The door came in on the second kick, frame split, metal torn. He filled the doorway like the last time I saw him, and then he filled my apartment. My brain didn’t think; it executed.

I pivoted hard to my left, dropped my center, let his mass do half my work, and sent him over my hip into my coffee table. It gave like particle board. He rose with fury and furniture embedded in his forearm. He came at me low and fast, a bull, and we went into the wall. The photo from my graduation fell and broke; glass skittered. I drove a knee into the meat of his thigh, aiming for a nerve that would shut the leg down, and he grunted and kept grinning. He found my shoulder with a fist and something inside it obeyed physics. The world flared white at the edges and went gray. He pinned my arms with his knees, leaned in close, and closed his hands on my neck with intent he’d been rehearsing for ten years.

He said a thing about my father designed to light the last match I had, and it did, and I bucked and twisted and understood it would not be enough. The edges of the room turned into a tunnel toward a vanishing dot, and my right hand found my phone by miracle or training or both. Swipe, tap, top of the messaging list. Three letters: SOS.

The black ate the white.

It spit me back out to boots and voices and Sloan’s face. She and two others from our unit lived within sprinting distance. They had kicked the rest of the door in and then Corbin back against a wall in the time my lungs spent deciding to work again. Military police did not ask permission to cuff a threat mid-scream. They slammed him handcuffed and swearing against laminate and escorted him to a place where doors lock from the other side.

I learned later Sloan didn’t dial 911. She called our team leader and a corporal who can break any lock with his shoulder, and then she hit the phone tree we never put on paper. Soldiers show up. It’s not a motto. It’s an instinct.

I woke in the hospital with Sloan asleep in a plastic chair, her boots on the seat, her neck in a position that would require ice later. On the table sat donuts. I cried about that more than my shoulder. Captain Rostova and Colonel Thorne arrived later—their collars full of authority and their faces full of fury on my behalf. “An assault on one of my soldiers,” the colonel said, voice low like weather, “is an assault on the United States Army. We will not let this stand.”

My mother had been found in the truck outside, small as a bird, eyes emptied out of language. They kept her across the hall and called it catatonia. I stared through the reinforced glass and saw a woman I didn’t recognize except as shape. The anger I had been saving for her withered and left pity behind like rough linen.

The lawyer from JAG—Captain Monroe, competence in a bun—arrived with a recorder and a warm presence that didn’t ask me to perform bravery for it. “Tell me everything,” she said. And I did, the way a soldier tells a story: clearly, with order, with reference points and coordinates, without begging for belief.

The tribunal was quiet rage disguised as process. Monroe built a case like a bridge, piece by piece, so that by the time the defense tried to step onto it with their “troubled stepdaughter” narrative, they fell through. When the attorney asked if I had a history of “defying authority” at home, the first row of my unit stood up in dress uniforms without speaking. The sound of two dozen soldiers rising at once is a sound you feel in your bones. The lawyer sat down soon after.

The verdict came back guilty on every count we had asked the court to consider. Attempted murder. Aggravated assault. Interstate stalking. The judge used the word maximum and then made it a number. The door closed behind Corbin and stayed closed.

The day my mother left the hospital, we didn’t talk about forgiveness. We drove to Palos Verdes where my father used to stand with his hands in his pockets watching the water like he had built it. We sat on a bench and let the crash carry the conversation we couldn’t have. “I’m sorry,” she said finally, without the deflection or the explanations I used to think were her. “I was so scared for so long. I didn’t know how to be your mother.” I took her hand—the one that had signed my enlistment because she could do that—and squeezed it. “I know,” I said. It was more than I ever thought I’d tell her and less than she deserved. It was what we had.

The scar where his fist caught my cheek was a line I didn’t ask a plastic surgeon to soften. I touched it when I needed to remember what my face had endured and what it could. I asked the colonel for permission to build a pilot program. He gave me more than permission; he gave me staff and a war room and the ears of commanders who liked results. We called it Operation Safe Harbor because soldiers love a name. It was a hotline that doesn’t route to voicemail, a network of safe houses that understand security clearances and chain of command, a manual for seeing what we have trained ourselves not to see.

The calls came. Not just from women. Not just from spouses. From privates afraid of sergeants, from lieutenants afraid of civilians, from families stationed too far from where help usually arrives. We trained first sergeants to spot patterns. We gave commanders language to intervene. We told stories with the names redacted and the impact intact. We turned the thing I survived into a map.

Part Two

The night before midnight came back around—one year later, almost to the hour—I stood in my kitchen and watched rain smear the world into impressionism on the other side of the glass. I made tea the way my mother likes now—too sweet and the mug too hot—and listened to boots on my front step. Sloan came in without knocking, bringing cold air and a grin. “You sleep yet?” she asked.

“Not anymore,” I said, and she laughed like I had finally made a joke she approved of.

On my table sat a stack of case files—names and numbers changed, trauma intact. Operation Safe Harbor had been more successful, faster, than my cautious modesty had predicted. The stories were not tidy. They never are. But in the margins were notes from COs who had learned to ask better questions and from privates who had learned to answer honestly. In the top case, a colonel had scrawled, “Sergeant Mills, your program saved a life this week. Thought you should know.” It’s not a medal. It’s better.

We drove to the base auditorium the next morning because the colonel had insisted on a ceremony and I had lost the argument. Soldiers do at least two things well: resist praise and tolerate praise badly. The room filled with uniforms and civilians. My mother sat in the front row with a cardigan buttoned wrong—old habits are stubborn—and Sloan sat beside her with her boots tucked neatly and her eyes scanning exits because she can’t not.

Colonel Thorne stood at the lectern and did the thing men like him are underpaid for: he used his voice like a resource. He talked about service that extends beyond a contract and about battles that don’t end when a deployment does. He said my name like it was a rank. He pinned a commendation on my chest, and when the photographer’s flash caught the metal, I felt the weight of it like accountability, not achievement. I stepped to the microphone and spoke about waves and fences and cards tucked into hands that don’t know what to do with them. I didn’t say Corbin’s name. I didn’t have to.

After, a lieutenant I didn’t know approached, his jaw unsteady. “My sister,” he said, “is safe because of a call she made to your hotline.” He didn’t cry. I did. My mother wiped my cheek with her thumb the way she used to and then apologized and then laughed because she didn’t have to anymore. We drove to the ocean and let it applaud for us.

The judge’s letter arrived in spring, formal and ordinary, announcing what I already knew from the JAG office: Corbin’s last attempt at an appeal had failed. I didn’t feel triumph. I felt the relief that comes when a door stays locked after you test it a second time at night.

I still woke sometimes at 2:13 a.m. because that’s when certain nights stop pretending. I still checked the deadbolt twice even though my brain knew it had been enough after one. I still bought the brand of cereal I couldn’t afford when I was seventeen and ate it straight from the box in my pantry like a teenager hiding from a chore. Healing is not a straight line; it’s a coastline.

My mother started over with the cautious joy of someone who keeps flinching and then apologizing to nobody. She chose a small apartment ten minutes from mine—though not on base and not under any man’s name—and planted a basil in a pot she keeps under-watering. She read whole books and told me about them. She attended group therapy and learned the language for a thing she had lived so long she didn’t know it had a name. She kept the hotline card I gave her in the drawer by the phone—not because she needed it now, but because she wanted to feel its weight.

When I asked her once, driving the long way home because we liked the bottle-brush trees that bloom near the back gate, if she ever wished we had done things differently, she stared out the window like she was watching for weather and said, “We did the best we knew until we knew better. Then we did better.” It is not scripture, but it could be.

The first time we drove back to Santa Monica and I didn’t bring a board, she didn’t bring a book. We brought sandwiches and sitting. We watched the sets roll in and break, and we didn’t talk until we did. “He would say, ‘Don’t turn your back on it,’” she said. I nodded. “He was right,” I said. Then: “So were you, the night you signed.”

There are parts of the story I did not include in the report. JAG didn’t need them. The tribunal didn’t help them. They are not evidence. They are details you keep so that when you wake up in the morning and see your face in the mirror, you recognize it as yours. The way Sloan sleeps in chairs and leaves donuts. The way Captain Rostova says my last name without shouting and makes it sound like a compliment. The way the colonel sends a Christmas card to my mother now signed “From your Army family,” which causes her to cry and then be embarrassed and then laugh at herself for being embarrassed.

Sometimes, when new soldiers show up to the Safe Harbor brief, I see a thirteen-year-old kid trying not to take up space in the back row of the family photo. I look for them after, in the hallway or the parking lot, and I say, “You don’t have to be as brave as you think to start. You have to be exactly as brave as you already are.” It is hokey. It is true.

And because stories like deals get better terms with closure, I will tell you this:

Six months after the tribunal, the base held a 10K. I ran it because Sloan refused to let me “miss a perfectly good opportunity to suffer for fun.” We were two miles in when a woman stepped from the cheering crowd and called my name. She wore the cautious face of someone trying to be certain without making a scene. “Sergeant Mills?” she asked. “I’m Dr. Kline. I run the counseling center off-post.” She took a breath. “A woman came in last week. Older. Quiet. She brought a card with your program’s number on it and said, ‘My daughter gave me this. I didn’t know I was allowed to use it.’ She’s safe now.”

I was not allowed, technically, to stop on the course. I did. Sloan cursed, then doubled back, then looped her arm through mine and walked me to the curb. “You okay?” she asked, even though she knew the answer. “Yes,” I said, because sometimes the truth is simple.

At midnight on a stormed-out Tuesday, my stepfather broke into my apartment and nearly killed me. The SOS I thumbed into my phone brought soldiers to my door like a cavalry I did not know I had earned. They hauled him away, and they sat with me until morning, and they didn’t leave a hole behind when they left; they built a bridge.

I have learned that family is a verb. It’s an action, not a blood test. It’s a phone tree that doesn’t ask if you deserve to be loved before it shows up. It’s a captain who makes room on a training schedule for grief. It’s a mother who signs a paper terrified and right. It’s a line of uniforms standing up as one, saying without moving their mouths: we see you. We see you.

And it’s a woman standing on her own porch, locking the door because she can, and then walking down to the water in the morning and facing the waves.

END!

News

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

My Parents Demanded I Sell My House to My Sister or Be Disowned—But Her CEO Already… CH2

My Parents Demanded I Sell My House to My Sister or Be Disowned—But Her CEO Already… Part One My…

They Sold My Late Husband’s Rolex To Fund Their Luxury Vacation. The Pawn Shop Owner Called Me… CH2

They Sold My Late Husband’s Rolex To Fund Their Luxury Vacation. The Pawn Shop Owner Called Me… Part One The…

Dad Mocked Me for Studying 9 Languages—Then My Commander Said 6 Words. He Went Pale… CH2

Dad Mocked Me for Studying 9 Languages—Then My Commander Said 6 Words. He Went Pale… Part One They say rooms…

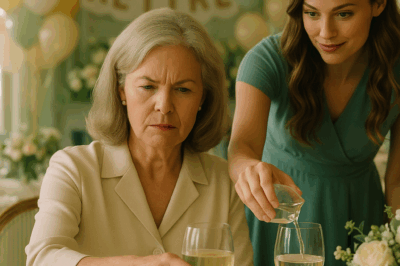

At My Retirement Party, My Daughter In Law Slipped Something In My Drink — So I Switch Glasses. CH2

At My Retirement Party, My Daughter In Law Slipped Something In My Drink — So I Switch Glasses. Part One…

“Grandma, My Parents Are Going To Take All Your Money,” My Granddaughter Said. Then I Made My Plan. CH2

“Grandma, My Parents Are Going To Take All Your Money,” My Granddaughter Said. Then I Made My Plan Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load