At Family Dinner, My Sister Announced She Was Moving In—But I Had A Surprise…

Part One

My name is Maria, I’m thirty, and eight years of scrimping and hustling in Nashville finally turned into a set of keys. Not just keys—my keys. The day I slid the deadbolt open on the little East Nashville bungalow I had chased across a seller’s market like a breathless runner, I sat in the driveway and cried hard enough that a neighbor paused his leaf blower and gave me a thumbs-up. I laughed, wiped my face, and told myself it wasn’t just a house. It was the proof that all the nights of instant noodles, the side gigs, the “maybe next time” vacations had been for something.

My parents loved to brag about my independence. Mom would tell people at church, “Our Maria’s always been the responsible one,” and Dad would nod over his coffee like he’d built me in a shop. What they didn’t say—because it sat there in the silence between compliments—was that my older sister, Heather, coasted through life on a tailwind of their bailouts. If my childhood had a texture, it was the feeling of waiting my turn while Heather’s emergency took the front seat. When we were little, I’d save allowance for months to buy off-brand sneakers; Heather would cry in the department store until Mom sighed and said, “She’s going through a phase,” and walked out with a bag and an apology to the cashier for the scene.

The phase lasted two decades.

I worked two jobs the summer before college—pancake house mornings and grocery store nights—so I could show up on campus without a balance in collections. Heather partied through two expensive years at a private university Mom and Dad financed, then announced the professors were “too old-school” and dropped out. She “tried on” community college for a semester like it was an outfit that didn’t fit, quit again, and blamed the “toxic environment.” I went to a state school, took out loans, and answered phones at an ad agency until I didn’t just answer phones there anymore.

Marketing in Nashville is scrappy. Everyone’s friend’s cousin designs logos, and everyone’s cousin’s friend knows a guy who “does social.” I started as the receptionist who ordered the donuts, sucked up the quiet projects no one else wanted, learned how to build media plans while a client thought I was topping off their LaCroix, and climbed one rung at a time. Every paycheck, I skimmed something for the house jar. It got heavy, and then it got real.

The day my offer was accepted, my heart did an Olympic floor routine. It was a three-bedroom 1940s bungalow with hardwoods that had seen decades of feet and a backyard just big enough to be a promise. The price made me sweat, but the bones were good and the light in the kitchen hit the counter at ten a.m. like it was glad to see you. The mortgage approval took a small miracle and a dossier of my financial life thick enough to be a doorstop. By the time I signed, I knew the last four digits of my bank account better than my birthday.

We did a housewarming. Dad commandeered the grill like the captain of a very serious ship. Mom hung curtains and fussed with a plant that kept listing left. They gave me a hardware store gift card and the kind of proud smile that makes you forgive the next six things. Heather showed up two hours late with smudged eyeliner, no gift, and a story about a boyfriend named Joe who was a genius if only people understood him. When she finally noticed the house, she gave me a slow once-over like I was the hostess at a restaurant she was reviewing for free. “This place is huge,” she said, yanking a beer from my fridge. “You should let me throw a party here. My apartment is too cramped for my friends.”

“I’ll think about it,” I said, which is Southern for absolutely not.

For a while after I moved in, life felt like a checklist filling itself: paint the second bedroom sage, plant basil and hope, buy a real couch that didn’t tilt if you sat on the left cushion. Repairs were the price of admission. The water heater died two months in like it was protesting early retirement. A breaker kept tripping when I ran the hair dryer and the toaster at the same time. I learned the names of men with toolbelts and the smell of a check written for $1,900 at eight in the morning.

Meanwhile, Heather’s life stayed messy like it had signed a lease on chaos. She moved in with Joe, then out, then back in with the same energy as someone switching playlists. She tried event planning, then retail, then assistant manager at a coffee shop. Each job lasted ninety days or until a boss asked her to show up on time. Every termination had a villain and the villain was never Heather. Mom and Dad paid a month of rent here, a mechanic bill there, cleared her credit card balance twice and called it “a fresh start.” The starts kept getting fresher; the follow-through did not.

Last month, the mess hit a new setting. Heather got fired (creative differences with her manager, she said; the schedule said otherwise), and her landlord slid a thirty-day notice under the door that might as well have been a bomb. Past-due rent, noise complaints. She was thirty-three, jobless, and a week away from boxed life. Mom called me that night and sighed into the receiver the way Mom sighs when her heart is heavy and her patience is on a walkabout. “Family needs to stick together in times like these,” she said.

I said “Of course” because that is what you say when your mother is speaking into the air more than to you, and because I didn’t yet know what that sentence would soon try to cost me.

The next week, my parents called more than usual—once on Tuesday, twice on Thursday. “We need to discuss some family stuff,” Dad said. “Better to talk in person.” When I tried to pry, he coughed and changed the subject to the Titans. Meanwhile, Heather started texting me like a landlord. What’s your Wi-Fi speed? Which bedroom gets the most light? Do your neighbors mind music at night? When I asked why, she sent a winking emoji and a just curious. My gut did a slow roll.

While the texts stacked, the house decided to remind me who owned who. A friendly drip under the kitchen sink turned into a plumber with a small flashlight and a big sigh. “Main line’s shot,” he said, and wrote down a number with a seven and three zeros and the kind of shrug that says, I don’t set the price of pain. I called Karen, my financial advisor, the woman who had looked at my budget two years ago and said, “You can do this, but you are walking a tightrope and I am not holding the net.” She ran the numbers and didn’t flinch. “Between the mortgage and these repairs, you’re burning at both ends,” she said. “I know you love this house. But the market is hot. If you sell now, you leave with your head high, not underwater.”

I cried when I hung up. Then I did what people call practical and I used to call betrayal. I called Sarah, a colleague who sells houses like she’s playing chess. She came over with a tape measure and the kind of shoes that don’t apologize for being expensive, praised my light fixtures, clucked sympathetically at the plumbing, and said, “You can list this for twenty percent more than you paid. I have a couple who just lost a bid two streets over. They’re preapproved, and they’re the kind who bring muffins to closing.”

They toured while I was at work. By that night, they had offered ten percent over asking with a rent-back clause that would let me stay thirty days past closing while I found my next place. It was the kind of offer that makes your hand sign while your heart catches up. I took it.

I told no one. Not because I love secrecy, but because I knew what my family would do with the information: line up their opinions like the fancy plates Mom only uses twice a year, and expect me to set the table with my savings. I decided I would tell them once contingencies cleared and checks had names.

Which is how we arrived at Sunday dinner with more sparkling wine than usual sweating in an ice bucket and Mom using the fancy plates for meatloaf.

Sunday dinners are ritual: Mom cooking something with carbs and comfort, Dad opening a bottle of “saved” red and talking halfway through the pour about how it was wasted on us, me arriving at five on the dot because I’m the only one in the family who can read a clock. That night, the table was set like a magazine spread and the house hummed a little too high. Mom kept checking the time. Dad stood at the front window pretending to watch a neighbor’s dog pee on the mailbox. When Heather arrived—twenty minutes late, dressed in a blazer instead of her usual leggings—she handed Mom a bottle of wine with tissue paper like she was presenting a diploma.

“Thought I’d bring something for once,” she said, and winked at Dad. The wink had a job.

We sat. Dad took the far end; Mom put me to his right and Joe to Heather’s left. Mom served pot roast and mashed potatoes like fuel for a reckoning. She kept steering conversation to square footage. “That big old bungalow must feel so empty with just you rattling around in it,” she said lightly. “All those rooms. It’s not good for a young woman to live alone in a big house like that.”

“I like the space,” I said. “The second bedroom is my office. The third is where the vacuum goes to feel appreciated.”

“Families ought to stick together,” Dad added. “Especially when times are tough.”

Heather kept glancing at her phone. The sparkling wine waited in its bucket like a prop. Joe stared at his plate like mashed potatoes had secrets. After dinner, Mom brought out peach cobbler and four champagne flutes she’d gotten as a wedding gift and used exactly… twice. Heather stood with a grin like a game show host. She peeled the foil, popped the cork, and poured the bubbles.

“Time to share some news,” she said. “Every problem’s got a solution.” She lifted her glass in a toast and glanced at my parents like a cue.

“To new beginnings!” she announced brightly. “Starting next weekend, Joe and I are moving into your house, Maria. Just until we get back on our feet, of course.”

There was a beat where the room pretended nothing had happened. Then there was a beat where everything had. Mom beamed, Dad nodded, Joe looked like he wished to be a fork. Heather smiled at me the way a person smiles at the waiter who is about to hand them the dessert they didn’t order but will eat anyway.

“We’ve talked it through,” Mom said quickly. “It makes so much sense. You have all that space, and Heather and Joe need a stable place while they sort things out. You work late; you won’t even notice them! They’ll chip in for Wi-Fi or something.”

Dad put his serious voice on. “Family helps family, Maria. You’ve always been the reasonable one.”

There it was—the stage, the script, the assumption that I was a character written into their plan. I took a breath, reached for my purse, and slid out a manila envelope with a weight you feel in your elbow. I set it on the table in front of my plate and pulled out the papers, the signatures, the numbers like a magician revealing a dove.

“That’s a real interesting idea,” I said, my voice calm in the way that happens when the choice has already been made five times in your head. “But there’s a problem with your plan.”

Mom smiled like she wanted to meet me halfway. “What’s that, honey?”

“I sold my house last week,” I said. “The buyers take possession in thirty days.”

Silence rearranged itself into a fourth chair at the table. Dad’s eyebrows lifted like blinds. Mom’s mouth fell open then snapped shut. Heather’s smile slid off as if someone had unhooked it.

“You’re kidding,” she said finally, a laugh catching on the word. “This is to get back at me.”

I spread the closing documents between the candles. “Inspection Tuesday. Contingencies cleared Wednesday. Closing Thursday. They have a six-year-old who’s been planning his treehouse for two days and counting.”

Dad grabbed the paperwork and scanned. He is not a lawyer, but he plays one in any room with paper. His face hardened at the word binding. “Why would you do this without talking to us?” he asked, as if my bank account filed a change-of-address form with his.

“You mean the way you all decided my house was a group project?” I said.

“That’s different,” Mom snapped, blush rising. “We were trying to help everyone.”

“How does volunteering my home help me?” I asked, more tired than angry. “The plumbing. The mortgage. The math. I was drowning and you were handing me a rock.”

Heather slammed her flute down hard enough to chime. “You did this to screw me,” she said. “You knew I was having a hard time. You sold it to make me look stupid.”

“This isn’t about you,” I said. “Not everything is.”

“Enough,” Dad said, which is what he says when he wants noise to stop without admitting its root. “Is there any way to undo this? Explain to the buyers? They might—”

“Call their lawyer?” I said. “Return the earnest money? Sue me? No.”

“We could help with the plumbing,” Mom said quickly. “Cover some bills while they stay—just for a bit.”

“The sale is done,” I said. “Even if it weren’t, the answer would still be no. Heather is thirty-three. She can apply for apartments like every thirty-three-year-old who likes leases.”

Heather’s chair scraped back. She stood, shoved the papers toward me, and went for the door with Joe in her wake. Mom half rose, then sank into her seat when I shook my head.

“She’s not going to be homeless,” I said, as the front door banged and the hallway sighed. “She can get a roommate or she can move in with you. You turned her old room into a yoga studio; you can roll up a mat.”

Dad cleared his throat and looked at the family photos on the wall like they might help. Mom’s eyes went shiny. “You’re so strong,” she said. “Heather struggles in ways you don’t.”

“Because you won’t let her,” I said. The words came out sharper than I intended, and also exactly how I meant them. “Every time she falls, you put a cushion under the floor and call it love.”

We argued for another hour in circles that led back to the same place: they believed in family as a house with one set of walls I built and everyone else lived in; I believed in family as doors you knock on, not doors you break down. Finally, I stood, put the papers back in the envelope, kissed my mother’s forehead, and told my father I loved him. He walked me to the door, hugged me too hard, and whispered, “I’m proud of you, even if I don’t get all of it.” It wasn’t enough. It was something.

I drove back to a house that wasn’t mine for long, put the envelope in the drawer with scissors and rubber bands and one lonely tape measure, and let the relief arrive in small, bright fragments: I had said no, and the ceiling did not fall.

Part Two

The next morning my phone performed a symphony of discontent. Heather’s texts started in a major key—I can’t believe you—modulated to minor—you ruined everything—and then went discordant—I told people I was moving to East Nash and now I look stupid. I responded once: I sold my house for my own reasons. Your housing isn’t my responsibility. After that, I let the bubbles float without landing.

Mom’s voicemails were the old melody sung at a new tempo: “We’ve been thinking… what if we help you find a new place with an extra room for them? Just until they’re stable.” Dad tried the pragmatic verse: “Loan her a deposit. Just to get her into somewhere decent.” I said no to both with a steadiness that felt like learning how to stand again. Word spread across the cousin grapevine; Aunt Linda called to clap me with “family duty,” and Cousin Emma emailed to say I was being harsh. I considered composing a sermon on boundaries and then opened Zillow instead.

The buyers let me rent back for a month after closing. I took that month and turned it into triage and then into a plan. The certified check went into a high-yield account where I watched the number with a guilty thrill; then I paid off the last of a credit card that had been a shadow at my elbow for too long and funded an emergency account with actual air in it. My shoulders lowered two inches. I started touring apartments with Rachel, a colleague who has a sixth sense for buildings that have both charm and not-my-problem maintenance. A one-bedroom loft in Germantown called me by name: a former warehouse with honest brick, tall windows, and the kind of kitchen that assumes you will actually cook sometimes. Rent was reasonable; repairs were from the landlord’s wallet, not mine. I signed.

Heather texted that afternoon. Need to talk. Coming over tonight.

I almost typed Don’t, then decided that if a storm was going to break, it might as well do it where the roof was still mine. When I pulled into the driveway, she was on the front steps with her arms crossed like defense and a car idling behind her. Joe was not there, which made the air feel less combustible but also less contained.

“Nice of you to give a heads-up,” I said, unlocking the door.

She walked in like she was already familiar and glanced at the half-packed boxes. The walls looked naked without my art, and the living room felt like a stage being struck after a play. “So you’re really doing this,” she said, as if I’d announced a move to Mars.

“It’s done,” I said. “What do you want to talk about?”

She sat on the couch and pushed a curl behind her ear in a nervous gesture I recognized from when she was eight and had broken Mom’s vase. “Mom and Dad said I should apologize for Sunday,” she said flatly. “So… I’m sorry.”

I waited. That was the entire sentence.

“And,” she went on, leaning forward, “I’m in a mess. The landlord won’t budge, Joe’s hours got cut, and I need a place for a bit. I know the house is sold, but maybe your new place has room. Or you could spot me a couple thousand for a deposit. I’ll pay you back when—”

“No,” I said, gentle as I could make it without making it soft. “My new place is a one-bedroom. And I’m not a bank.”

“So that’s it.” Her eyes went shiny, but the hurt came out as anger. “You’re fine with me and Joe on the street?”

“You have options,” I said. “Roommates. Studios. Mom and Dad’s guest room if they move the yoga mat. None of them look like you living in my house for free.”

“Roommates are for twenty-year-olds,” she scoffed. “Mom and Dad live in the middle of nowhere.”

“They live twenty minutes from downtown,” I said. “And they have a porch swing. You’ll survive.”

“You’ve changed,” she said, standing. “Miss Perfect with her job and her big plans. Have fun in your fancy loft while I—”

“I haven’t changed,” I said calmly. “I just stopped being useful to your worst habits.”

She left. The door closed. The smell of cardboard and lemon cleaner filled the quiet. I sat in the middle of the living room floor and breathed.

Moving day came like logistics and left like loss. The movers wrapped my sofa in blue quilts and carried it away like a patient. I scrubbed the oven because I am the kind of person who cannot hand strangers an appliance with a secret. The buyers arrived with their little boy, who kept telling me about his new bedroom and how he was going to hang a map on the wall so he could “travel while sleeping.” I put the keys in his mother’s hand and felt something unclench in my chest.

The loft didn’t feel like home at first. The ceilings were tall enough that my thoughts echoed. The concrete floor kept secrets of decades. At night, the city made its own sounds—sirens, laughter, a garbage truck, a song from a bar down the block that got the chorus wrong but kept trying. But the first of the month arrived and my bank account did not have a panic attack. I bought a rug that made the place look less like a photo from a magazine and more like a life. I slept through the night without waking to the thought, What will break next?

Across town, my parents learned what consequences look like when you house them. “She’s staying here for now,” Mom told me on the phone two weeks later, sounding both relieved and exhausted. “She leaves her coffee cups everywhere and Joe eats all the yogurt.” I murmured sympathetic noises and did not offer to come organize the fridge. “We made rules,” Mom added, and I heard something new in her voice—structure, not pleading. “Rent due on the first. Chores. No late nights. Your father even put it on paper. A lease, he called it.”

I nearly dropped my phone. “You and Dad made a lease?”

“Don’t sound so shocked,” she said, but she laughed. “We’re learning.”

A week later, Dad called with a kind of pride he usually reserves for football. “Heather has a job interview,” he said. “Reception at a dental office. She asked me to do mock questions. I told her to show up on time and not call the dentist ‘Doc’ unless invited.”

“What changed?” I asked.

“We did,” he said simply. “Your mom means the rules.”

At our first Sunday dinner after the explosion, the air was cautious but breathable. Heather wore a blazer over a T-shirt like armor. Joe shook my hand like we had just met and wanted to start over. Somewhere between the green beans and dessert, Heather said, “I got the job.” She didn’t meet my eyes when she said it. “Phones and scheduling. I can move up to office manager if I stick with it.”

“That’s great,” I said, and meant it. “Your event planning experience will help with the logistics.”

She flicked her eyes toward me, then down at her plate, as if permission to feel proud needed a quiet place to land. There was no hug. No teary “I’m sorry” montage. Just a new sentence added to the family vocabulary: I’m working.

When Mom and I cleared the table, she pulled me into the kitchen and shut the door with her hip like she used to when secrets were cookies. “I owe you an apology,” she said softly. “Your father and I… we made you our safety net. It wasn’t fair to you. And it wasn’t love the way we thought it was for her.”

“Thanks, Mom,” I said. It was not everything. It was not nothing.

The months that followed were not a movie—no swelling soundtrack, no montage where everyone learned lessons at the same time. Heather complained about the early shift; Joe learned to meal-prep so they wouldn’t hemorrhage money on takeout. Mom bit her tongue when Heather left laundry on the machine and then handed her a basket and a timer. Dad discovered you can tell your adult child to the face, “Rent is due,” and the sky does not fall.

Heather and Joe found a small apartment near a bus line. It had the kind of beige carpet you buy by the mile and a balcony too small for anything but a chair and a plant. They invited us for a housewarming that included paper plates and a candle that smelled vaguely of citrus and determination. I brought kitchen towels and a grocery gift card and tried not to give advice about where the couch should go.

On my way out, Heather walked me to the door. “I was mad about the house,” she said without bluster. “I thought you did it to stick it to me.” She shoved her hands in her pockets. “I get it now. It still sucks. But I get it.”

“I didn’t expect you to like it,” I said. “Just to understand it wasn’t about you.”

That was the sidebar we got instead of a full reconciliation. It was small. It was enough.

My loft turned into mine. I hung the art I couldn’t part with and bought a secondhand bookcase that made the wall look like it had always had something to say. I started taking a Saturday morning photography class at the community center because I had energy that didn’t belong to a clogged drain. The job stabilized; the brewery campaign landed; my boss used the phrase “year-end bonus” like it wasn’t mythical. I started looking at condos not as trophies but as houses that might fit a future I wanted, not a future I thought proved a point.

Six months after the house keys changed hands, I stood barefoot in a two-bedroom condo in a quiet stretch of Nashville that has sidewalks and shade. The balcony had a view of three trees and a sliver of sky, and the kitchen had a full-sized dishwasher that did not sound like a metal band. Rachel raised an eyebrow. “Well?”

“I think it’s the one,” I said, and felt what relief feels like when it’s not just the absence of fear but the presence of something kinder: sanity. I made a down payment that did not set my hair on fire. My monthly costs left room for a life. The emergency fund stayed an emergency fund and not a plumbing fund in disguise.

Family dinners got easier. No one tried to move anyone into any house. Mom told stories about her knitting group, Dad argued about sports with the TV, and Heather talked about a promotion track at the dental office like it had been sitting in the room the whole time waiting for her to notice. At Christmas, she gave me a framed photo of my old bungalow’s front porch with a handwritten note on the back: You taught me something I didn’t want to learn. Thanks anyway. It sits on my bookshelf between a plant I forget to water and a camera from a thrift store that doesn’t work and doesn’t have to.

One night in late spring, while the city hummed and a breeze off the river did its best impression of cool, a text from Heather buzzed. Got a raise. Taking Joe to celebrate. Thought you should know. No request. No strings. I typed Proud of you and meant it and put my phone face-down and went back to the book I was reading about gardens in cities and people who decide the space they have is worth tending.

Here’s the thing no one tells you about boundaries: the first time you set one, you think the earthquake you feel is the world. It’s not. It’s your old life falling apart and your new one settling into place.

A year after I said I sold my house, I hosted dinner in my condo for the first time. It wasn’t a party—just bowls and forks and a recipe my friend swore would work even for people who have a fraught relationship with their oven. Mom brought a salad with too many nuts; Dad brought a pie; Heather and Joe brought soda and a story about a patient who brought the office donuts because “you people saved my sanity.” We ate at the table I had bought secondhand when I was twenty-two and proud of owning a table. We cleared the plates without talking about duty or worth. When they left, I stood on my small balcony and watched Nashville do that thing it does where it pretends it’s smaller than it is and bigger than it knows and thought: I’m okay.

At that Sunday dinner months ago, when Heather raised her glass and announced she was moving in, she thought she was unveiling a plan. She didn’t know my surprise had signatures. She didn’t know what the envelope meant because she never had to. Now she knows. We all do. My parents learned that love looks like rules with a hug. Heather learned that shelter is sweetest when you build it yourself. I learned that a house can be a dream and a trap, and that selling one can be both a grief and a rescue.

If you’re looking for a moral, I don’t have one that fits on a napkin. What I have is this: sometimes the bravest thing you can do at a family table is to unfold a manila envelope and tell the room I choose me. Sometimes the surprise is not a fireworks moment but the quiet where your new life unfurls and stays.

The last box I opened in the condo held the small stuff that gets thrown together at the end of a move—batteries, a handful of screws, a birthday card from a friend, a key to a door I no longer own. I held the key, smiled, and put it in a drawer with the scissors and the rubber bands and the solitary tape measure. Some souvenirs aren’t meant to open anything. They’re just there to remind you that you can.

END!

News

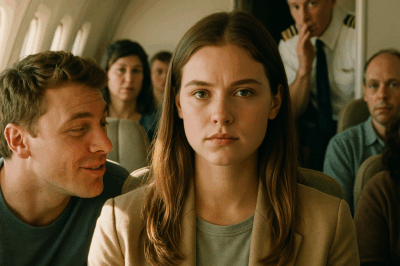

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives. CH2

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives …

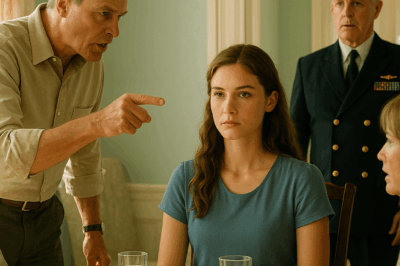

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” CH2

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” Part One My name…

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… CH2

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… Part…

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… CH2

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… Part One My…

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. CH2

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. Part One My…

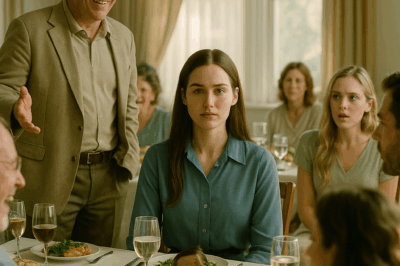

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load