At Family Dinner, My Mom Threw The Bowl At My Face Because I Refused To Pour Wine For My Sister

Part One

My name is Jodie Hart. I’m twenty-six, and for most of my life I was the person who made life easy for everyone else. If you asked my parents they’d say I was dependable; if you asked my sister she’d call me her unpaid assistant. I was the one who mixed beach cocktails for group hangs, who scrubbed sand out from between flip-flop straps after parties, who ironed the sundresses and said yes when somebody needed a ride. I learned very early that keeping the rhythm of the household smooth meant never making waves.

On the night the bowl hit my face, the ocean breeze should have cooled us. Instead it thickened the tension, like humidity pressing on something already taut. The family dinner was the kind you can smell long before you arrive—grill smoke, citrus, cilantro, a pile of shrimp skewers that looked like a small holiday. Dad, Kurt Hart, presided in a polo the way he presided over his beachside hotels: with a kind of casual authority that ended arguments. Mom, Felicia, was bustling, carrying platters and giving the impression of an effortless hostess. Tawny—my younger sister—was stretched across a wicker lounger with a phone in one hand and a wineglass in the other, the very picture of ease.

It had simmered for a long time before that night. Our coral-painted bungalow sat a block from the Atlantic, a place where salt scented the curtains and visitors expected careful surfaces and perfect throws. Dad’s voice meant business in our house; his hotel chain paid for most of the neighborhood barbecues and the billboards up the coast. Mom had once talked about making a career of curating coastal weddings; life folded her into being a mother and hostess instead. Tawny grew up glorified for her lightness: she got a kiteboard when she was six; I got a mocktail shaker and instructions on how to be useful. By nine I was rinsing patio chairs, packing sunscreen, fetching towels, and smoothing the ripples from a life that, in public, precisely conformed to their needs.

I was the older child who scrubbed and calculated, who worked two summers at Dad’s front desk and then designed spreadsheets and budgets as if they were little altars. I mapped scholarships like escape routes. At twenty I landed a scholarship and moved to Orlando for university; the bursar’s office and long nights in the campus library were my apprenticeship. When the 2008 crash froze hiring, I came home to the bungalow with a degree in my hands and the kind of resume that taught restraint. Dad said he supported me—“Family’s the real deal”—but the reality was that a hundred small favors went to Tawny because it was easier than asking her to learn to answer a phone.

So that night, when Tawny snapped her fingers and said, “Pour it, Jodie, like always,” my body recognized the cue. My throat tightened, not only because the demand stung, but because it represented a decade of assumptions: that my labor would be invisible, that my priorities did not belong to me. A small, stubborn part of me that had been trained in libraries and budgets and quiet courage finally clicked. I set the bottle back.

“No way,” I said, my voice flat. “Not this time. Get it yourself.”

What followed happened so fast the edges both blur and sharpen in my memory: thirteen years of being the reliable one condensed into a single physical act. Mom’s face changed first—the practiced smile curdled, something volcanic rising behind the hospitality. The pitcher of sangria trembled in her hand. Dad looked up from his tablet, gaze narrowing but staying quiet, as if the household’s choreography must not be interrupted. Tawny’s eyes flashed with a smirk. She said, cool as a film cut, “Servants should know their duties.”

The words landed like a slap. I didn’t flinch at the insult; I flinched at the entitlement, at the assumption that my life belonged to the comfortable convenience of the family. When Mom moved, it felt preternatural—slow, a kind of motion that carried all the absence of thought and the drag of old practices. She grabbed the nearest salad bowl and threw it. Ceramic arced across the dining table and struck my face. Lettuce and vinaigrette flew. The edge of the bowl cut the line of my cheek and warm blood mixed with dressing.

The pain was immediate and double: a physical sting and a deeper betrayal. I remember standing there in a moment that had become too much compressed—guests with forks in hand, Dad frozen in a chair, Tawny’s smug half-smile, the neighbors awkward and watching. The only sound that registered was the thunk of an overturned chair. I pressed my hand to the cut on my cheek. Blood warmed my fingers. I turned and walked out more because I had to than because I wanted to. I didn’t shout, I didn’t cry; I locked myself in my room and let the storm rise properly only inside my chest.

The morning light made small things look ordinary. By then I had plastered over the cut with concealer and hidden the bruise. Mom knocked at my door, voice soft and frantic: Jodie, honey, come on, talk to me. I kept the lock engaged. Silence can be an enormous thing. The lock felt like a private revolution. I pulled my laptop out, saved photographs of the cut, and composed an email to a woman I knew in our neighborhood named Trisha Vale—Grandma Pamela’s old friend, a woman whose life outside of our family had always seemed more real than the staged domesticity of our bungalow.

It wasn’t that I was making a scene; it was that I had finally accepted the terms of a thing I had always felt but never named. The bowl—literal and symbolic—had been the last straw. Grandma’s old letters, which I’d found in an attic box months earlier, had been a catalyst. Pamela wrote fierce, unapologetic notes about owning your life: don’t pour for people who won’t pour back, she’d scribbled at twenty-two, full of the bar-room wisdom she’d earned. That scrap of counsel had lodged in me like a seed. The day the bowl cracked open my skin, it also cracked open the resolve within me.

I began a quiet, careful plan. If you’ve never had to disentangle yourself from a gilded dysfunctional family, let me say this plainly: the work is both small and massive. Small because you begin with choices—opening a bank account, stashing a few bills, gathering critical documents—and massive because you are dismantling a role that has been given to you since you were small. I watched the bungalow’s rhythms with new eyes. I learned how my mind had marked every favor, every “Oh, Jodie, you always make things easy,” as payment for being the good child. I catalogued infractions and I documented what I needed for departure.

I spent nights at the library across town—Dixie Highway Public, where the computers were slow and the fluorescent light hummed—sending applications to marketing agencies in Seattle, where past internships and Orlando projects had left me with cheery references I could call upon. I opened a credit union account with two hundred dollars I’d taken from an old beach bag tucked in my trunk. I scanned my birth certificate and social security card using the library scanner and made careful digital copies stored on an external drive.

Most important, I reached out to Trisha. She answered that afternoon with an invitation for coffee and a spare key to a downtown condo should things become tight. She handed me five hundred dollars, not as charity but as a stake to start. “Grandma Pam would have bet on you,” she told me, sliding the envelope across the table like an offer of partnership. And for the first time in a long while, I felt a thread of hope that wasn’t dependent on someone else’s approval.

I kept the surface calm at home. I played the part—the tidy daughter, folding towels, loading the dishwasher, pretending the bruise wasn’t a ledger of a moment when I had finally refused. I did not want them to see me pack, to see the plan in motion. “More lime, Jodie,” Tawny said one afternoon, as if nothing had changed. I complied with a smile that felt like a prosthetic. On the inside I circled departures and visas—job offers, a route north, the way to make the exit clean.

Then the call came: a hiring manager in Seattle wanted a phone interview. I climbed into my car on Thursday and took the call from the library parking lot, the wind flapping the paperwork. Hard work had taught me how to sell myself without apology: organizeable campaigns, grassroots UX experience, a capacity for clear storytelling. By the end the recruiter smiled through the line and said they’d send an offer. Ten days, they said. Ten days to leave the bungalow’s orbit.

Two weeks later, after one dinner where Mom stood in the lantern light and tried to make it clear I needed to “remember my place,” I produced the photos I’d taken on my phone: the cut, the blood smear, the remnant of a failing normalcy. The room stiffened. Mom’s composure dissolved; Dad’s chair creaked as if his frame needed readjustment to hold this new truth. Tawny’s smirk cracked into something smaller. I told them quietly and clearly: I’m leaving at dawn. I have a job in Seattle. I am done being your prop.

I left without fireworks. I left with a duffel, Trisha’s envelope, my grandmother’s letters, and the quiet proof of my resolve lodged like a stone in my pocket. The bungalow, in the rearview, looked like a stage that had finally gone dark. The ache went with me—guilt and grief and the solidity of leaving—but there was also the unshakable sense that I had chosen myself. That mattered.

Part Two

The first weeks in Seattle felt like waking from long anesthesia. Carrie Dunn, a college friend who had a third-floor walk-up in Capitol Hill and a spare key, took me in. The apartment smelled like coffee and thrifted books; it was small and crooked and, importantly, free of the choreography that had run my life. We ate takeout on a futon. I started work at a small eco-tourism marketing agency that hired me as a junior coordinator and gave me a chance to pitch actual campaigns. My experience in Orlando and the ways I had quietly learned to manage reservations and guest experiences fit oddly well with the new world of boutique sustainable adventures.

My days were busy. We created campaigns for small resorts that wanted to emphasize low-impact travel. I learned to manage analytics and craft messaging; I learned, in the quiet of measuring engagement and open rates, how to shape a narrative without someone else’s hand on its throttle. I fell into a community that didn’t glitter with entitlement. People here traded stories about hikes and labor and weekends working at community gardens, not about who had the better pickup truck. Garrett, a designer with a slow grin and soft hands, became a friend first and then something more. He knew what it meant to split chores and to expect partnership. In his company, I learned how small acts—like taking turns washing the dishes—could be radical.

We worked. We laughed. For the first time in years I slept without calculating the route of my exit. Thanksgiving was a small dinner at Carrie’s where the wine didn’t come with a ledger of social debts. I had thought leaving would be hollow and lonely; instead it filled with mundane, gorgeous, undramatic things.

Back in Miami, the bungalow’s life unraveled quietly. Mom spiraled. The neighbors who had once praised her party planning skills started to look away. The bowl incident circulated in dribbles—friends who had been there and remembered the flying ceramic, the cut, Dad’s silence. His hotel board learned of rumors; a disgruntled competitor probed offers and moved to undercut his contracts. Where there had once been a certain unassailable social capital, now there were awkward calls and a thinning roster of clients. The same ease that had approved Tawny’s shortcuts backfired when creditors and bills required steadier hands.

Tawny, too, found herself suspended from a position of leisure; the Instagram posts of beaches and cocktails were replaced by late night barista shifts and short-term gigs. The entitlement that had once bought her designer sunglasses couldn’t buy a mortgage. She texted once—“I get it now, Jodie, can we talk?”—and the words affected me as if someone tossed a small smooth stone that I didn’t want to pick up. Growth is not automatically our debt to fix. She could have chosen differently; she hadn’t.

Dad called once in the first year, voice clipped, asking if I could forward a resume to “people in Seattle.” The ask felt like a thin apology wrapped in paternal usefulness. Doctoring his request seemed immoderate after his passivity the night of the bowl. I refused to be levered into saving the old structure. The man who had asked me to be compliant had to live in the consequences. The bungalow, eventually, was put up for sale.

Professionally, the move to Seattle paid off. My campaigns picked up traction; a viral pitch for a small coastal preserve drew national attention. Three years in I became senior strategist at the firm, leading a team of five and mentoring other women who had been told their place was “helpful silence.” I began an online program of mentorship for young women stuck in enabling family dynamics. Sometimes students would write me messages about refunds and loans, and I would send them the letter of a woman who ran a bar and taught me—Grandma Pamela’s old line about owning the bottle. The phrase “Claim your seat,” once private, became a small guiding motto in my course.

Love, too, took an ordinary shape. Garrett and I rented a loft with exposed brick and plants in the window. We split the bills and the cooking. He held me the night I had a flash of a memory, the kitchen smell reminding me of the bungalow and the bowl. I taught him how to make a decent mango slushie; he taught me how to build a campfire and manage a campsite. We loved in ways that asked for reciprocity, not performance.

There were moments when I checked back—curiosity is a human thing. I would see articles: Dad’s hotel chain had lost some accounts and he had taken a step back. Mom’s neighbors whispered. Tawny had a small business start-up that burned through funds and then closed its doors. These weren’t moral punishments so much as the tidy consequences of enabling and expectation. The social scaffolding that had propped them up was unstable once economic reality leaned against it; it didn’t take violent thunder to make a house of cards crumble. It took steady pressure.

Two years after I left, Trisha wrote that Mom had called her in tears: “Tell Jodie I’m drowning.” The appeal might have been a human plea, but I had learned that I was not responsible for someone else’s repair work when they had thrown the bowl. You don’t absolve the person who hurt you by fixing their mess; that would be another role forced on you. I deleted the message and let the silence be my answer.

The bungalow sold to a young family with a small child who learned how to fly a kite in our front yard. In the months after the sale, I found a quiet satisfaction in the way my life had settled into its own architecture: work that meant something, a community that traded favors without expectation of martyrdom, a partner who celebrated ordinary chores.

As for mom and Tawny, the relationship with them became a slow calculus. I did not indulge in revenge; my refusal to pick up their pieces was itself a moral boundary. I supplemented my work with a small fund, named quietly for Pamela, sent in to community programs for women going back into the workforce—skill trainings and resume workshops. It was not charity to my family; it was an attempt to turn a private wound into a public repair.

There were small moments of contact—an email with a mother’s apology, a brunch with an aunt who still loved me—but none of them demanded I place my life back into old patterns. Tawny reached out once more, asking if I would help edit a cover letter. I did, as a teacher, not as a rescuer. She was doing the work; she had stopped asking others to pour for her. That, to me, was the kind of growth that deserved a response.

I never celebrated the bowl. I never framed the night as martyrdom. I kept the pictures—the cut, the smear, the small forensic proof of the thing that finally allowed me to choose myself—and I filed them with the rest of the archive of a life. Some wounds simply teach. They are not trophies.

The end of the story is not cinematic revenge. It is quiet and ordinary and, I think, better. It is about a woman who refused to be less than she was, who took resources in hand and walked toward something she wanted. It is about the slow work of rebuilding: the pivot from being a function in someone else’s story to being the author of your own. In the loft with Garrett, over a dish we cooked together, my phone would sometimes buzz with a message from a student who had left an abusive household and called to say “I found an apartment and a job.” Those were the tiny fireworks that mattered.

If there is a moral here it is not that families must be punished. It is that self-preservation sometimes asks for hard choices; protecting your dignity is not cruelty. When you are asked to be forever useful to people who are cruel, your refusal is not an outburst, it is a boundary. When you are poured into until dry, you are allowed—by the brutal arithmetic of self-sovereignty—to refill yourself elsewhere.

The bungalow sits in my memory like an exhibit: once appealing, now a cautionary piece. The bowl is not a trophy on a mantle, nor is it a relic we scream about at family dinners. It is a signal, a line in the sand. The night Mom threw it, I closed a door. When I left at dawn, I did not sprint away from tragedy so much as step toward a life where my hands and my labor would be my own.

Years later, when the sea wind ripples the curtains and I tell this story to a mentee over coffee, she will sometimes ask, eyes wide, whether I ever regretted the distance. I always shake my head. Regret, for me, would be staying. Choosing yourself is messy, costly, and lonely in ways that are honest. But once you choose the costs, the life you build becomes built on terms you set.

I do my work now in a room with uncurling plants and a soft rug. I have friends who refill my life. I have no interest in being anyone’s unpaid assistant anymore. Sometimes Garrett and I drive west to the ocean and stand on a bluff and look at the horizon. The water is wide and patient. You can’t unmake a life overnight, but you can choose where you anchor it. My anchor is steady because I chose it. The bowl was thrown, the cut healed, the door closed—and by morning I had already begun to rebuild.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

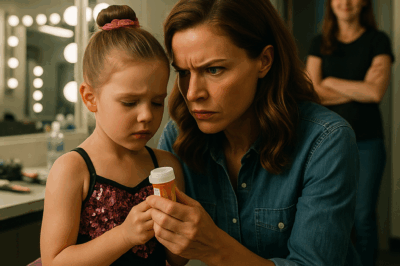

Sister Swapped My Daughter’s Medication Before Her Recital to “Teach Her Humility” CH2

Sister Swapped My Daughter’s Medication Before Her Recital to “Teach Her Humility” Part One The moment your child collapses…

My Husband Slipped Sleeping Pills in My Tea—When I Pretended to Sleep, What I Saw Next Shook Me. CH2

My Husband Slipped Sleeping Pills in My Tea—When I Pretended to Sleep, What I Saw Next Shook Me Part…

At Family Party, My Mom Gave Me A Painful Slap – While My Sister Got An iPhone 17 Pro Max. Then I.. CH2

At Family Party, My Mom Gave Me A Painful Slap — While My Sister Got An iPhone 17 Pro Max….

My Husband Danced With His Mistress at Our Wedding Anniversary, by Morning, He Was Homeless. CH2

My Husband Danced With His Mistress at Our Wedding Anniversary, by Morning, He Was Homeless Part One My name…

At Family Dinner, I Accidentally Saw My Mother And Sister Using My Fake Signature. CH2

At Family Dinner, I Accidentally Saw My Mother And Sister Using My Fake Signature Part One My name’s Veronica….

During the latest taping of The Five, the audience got a hilarious surprise when the atmosphere suddenly grew tense over something seemingly trivial.

During the latest taping of The Five, the audience got a hilarious surprise when the atmosphere suddenly grew tense over…

End of content

No more pages to load