At Family Dinner, My Husband Coldly Said: “We Need a DNA Test” — a Secret Hidden for 15 Years…

Part One

It began on a Tuesday, a day so plain it could have been cut from any week of any year. Leftover chicken hissed in the skillet. Potatoes reheated in the oven. My husband sat across from me with his phone propped against a salt shaker, fork moving from plate to mouth with the mechanical regularity of a metronome. He didn’t look up until he said it.

“Grace,” Thomas murmured, eyes fixed on a spot just past my shoulder, “I think it’s time we do a DNA test for Jacob.”

For a full breath I heard only the small, ordinary noises of our kitchen—the tick of the cooling oven, the hum of the refrigerator, the hollow clack when his fork hit porcelain. Then his meaning sank like a stone through water. Fifteen years of scraped knees and soccer games and science fair volcanoes, of fevers held through the night and hands squeezed under fluorescent lights, all the ways we had knit our lives into a net around a boy who called us Mom and Dad—and he wanted paperwork.

I tried to laugh it off, hoped he would look up smirking and say I’d misunderstood a bad joke. He didn’t. The look on his face wasn’t anger. It wasn’t even accusation. It was colder than that, as if he were reading a weather report he didn’t much care about.

He slept well that night. I didn’t. The fan turned a lazy circle over our bed, casting fat shadows that crawled along the ceiling while the hours dragged their feet. I could see him in the dim spill of the streetlamp: profile smooth as a coin, jaw set, eyes closed. The face of a man at peace. I lay beside him counting out, like beads, the nights we had soothed our son’s nightmares, the mornings we’d signed permission slips and packed lunches, the years we’d told each other we were doing all right. My chest felt tight; the house felt tight; I felt too large for my own skin.

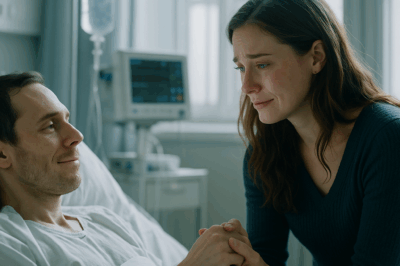

He left early the next morning without a word. Two days later, we sat side by side in a private clinic’s waiting room while “Lives of the Great Composers” played too loudly from a hidden speaker. Jacob thought it was a “checkup.” I didn’t correct him. The nurse swabbed our son’s cheek, cheerful as a game show hostess, and I smiled back because that is what mothers do when their child’s eyes find them: they smile, even when they want to bolt.

On the drive home Thomas kept both hands on the wheel and looked straight ahead, the way he does when he thinks he is being most reasonable. That night he took his laptop into the study and locked the door—a small locksnap that seemed to echo all through the house. He started carrying his phone into the bathroom. He stopped leaving his bank statements on the kitchen desk. Small changes, petty ones, but they nibbled at the edges of me in a way I could not explain.

“Is Dad mad at me?” Jacob asked three days in, nudging peas around his plate with his fork. He is fifteen and already taller than I am, and there are moments he looks at me with a startling imitation of his father’s seriousness that makes me catch my breath.

“No,” I lied gently, “he’s just tired. Work is hard right now.” The lie tasted metallic, but I couldn’t find a better one. How do you explain to your child that his father is auditing him.

I didn’t tell my sister, Anna. I didn’t tell Vicki, my oldest friend, who has never met a problem she didn’t want to shepherd firmly toward a solution. I wore the secret like a stone under my sweater and moved through the days hoping not to knock it against anything sharp.

The results were ready a week later. The doctor’s office was everything doctors think is soothing: art prints of pastoral scenes, a plant I suspect was plastic, a bowl of hard candy no one ate. The man himself sat behind a desk of dark wood, his glasses perched low on his nose, his face arranged carefully into a mask of gravity and compassion. He shuffled paper. He cleared his throat.

“According to the results,” he said, the words as slow as they were precise, “the probability of paternity is zero. Mr. Caldwell is not the biological father of Jacob.”

I felt the world tilt. Air, sound, the burn of tears—everything doubled and then halved. Beside me Thomas leaned back in his chair, exhaled through his nose, and said softly, “I knew it.”

The doctor wasn’t finished. He looked down at the file again, then up at me. His tone changed, went from rote to careful.

“We also test maternal DNA as a control,” he continued. “Mrs. Caldwell, Jacob is not biologically related to you either.”

There is a particular silence that follows disaster. Not the silence of an empty room, or of a paused conversation, or of the breath before a shout. It is the silence that makes you feel as if sound has been removed from the world, as if you are listening underwater. I sat in that silence and stared at the man who had just told me I hadn’t given birth to my son, and I tried to make his mouth say something else.

By the time we got home Thomas had moved his things into the guest room. The hallway, ordinarily a river of dropped shoes and careless jackets and Jacob’s perpetually lopsided backpack, felt like a museum. He closed the door. The soft click reverberated through me like a gunshot.

I cleaned. When I cannot bear my life, I scrub it. The box I keep on the top shelf of the bedroom closet—hospital bracelets, Polaroids, a wrinkled copy of the discharge form—came down onto the kitchen table. I spread our history in front of me and looked hard.

In one photograph I had never studied closely, a nurse hovered over my shoulder while I cradled a swaddled bundle. I had always assumed the expression on her face was the universal worry of a young nurse with a brand-new mother. Now I saw it differently. Her name badge was crooked, half hidden in the fold of her scrub top. Her hair had fallen loose, a curl stuck to her cheek. She wasn’t worried; she looked startled, as if someone had called her name just as she’d put a hand on the wrong thing.

The next morning I drove back to Harrisburg General for the first time in fifteen years. The entrance was different, but the smell—the clean, chemical optimism of hospitals—was the same. I asked at the desk to see someone about a possible newborn identification error in January of 2009. I braced myself for a version of “no.” Policy is a helpful armor when you don’t want to be a person.

A woman with silver hair and a badge that read DIANA WHITMORE: PATIENT SERVICES DIRECTOR invited me into her office and closed the door. “I remember you,” she said, and I began to cry because a piece of the universe had spoken kindly to me. “Emergency C-section. It was a rough night.”

She pulled a paper ledger from a tall cabinet. “Most records are digital now, but that week we still had backups.” Her finger traced a list. “Four deliveries. Two boys, two girls. Staff was thin. We had three nurses on the floor. One was new.” She tapped a line with a polished nail. “Natalie Brooks. She left after six weeks.”

“She’s in a photograph,” I said, my voice a torn thing, and showed her the picture. Diana’s mouth pressed into a line.

“I won’t give you names without a court order,” she said, then added in a soft voice as she closed the ledger, “but I can tell you, as a woman, that mistakes happen when the people making them are very young and very tired. If someone made one that night, it wasn’t done in malice. That doesn’t make the damage smaller. It does make it human.”

Vicki didn’t say “I told you so” when I finally told her. She put two cups of coffee on her kitchen table and slid a napkin across to me like a referee sending a player to the bench and said, “You need an attorney.” Christopher Lane had the kind of face that makes you read people generously—sharp eyes, warm voice, a steady way of folding his long hands on the desk while you bleed all over his office. He listened. He asked the sort of questions that untangle knots you didn’t know you had tied. He warned me the truth had teeth. “If you go down this road, it won’t end with answers and a tidy bow,” he said. “It will end with courtrooms and news and a lot of feelings. Are you ready?”

“I’m already in it,” I said. “Put me in the game.”

His investigator found Natalie seven days later in a town where the main street had one stoplight and a diner whose sign had lost its “R.” She ran a flower shop with pink shutters and a scent that made your chest open. When I walked in, her face blanched, and then did something else—something like relief worn thin.

We stood in a back room among buckets of carnations and eucalyptus. “I was twenty-one,” she began, hands worrying a length of ribbon. “Two women in labor. One surgeon in a rage. One nurse on her second overnight. I put a bracelet on a wrist I thought was right. Later… later I wasn’t sure. I told my supervisor. She told me to keep quiet or ruin families and my career. I left. I have thought about it every day.”

“Do you remember the other mother?” I asked, voice a rasp. “Red hair,” she said. “Husband did construction. Monica. Monica Reed.”

Vicki drove me to Monica’s modest brick house two days later, because grief is a passenger who shouldn’t be allowed to navigate. The front yard had a tricycle abandoned mid-adventure and a wind chime that sounded like a lullaby. Monica opened the door with one of those faces that holds welcome and caution together. When she saw me, something in her softened and something else set.

“You were at Harrisburg General,” she said. I nodded. I did not have a graceful way to say what came next. “I think our babies were switched.” She pressed her palm to her mouth. The boy on the couch pulled an earbud out, and I saw Thomas’s jaw on a face that wasn’t Thomas’s son.

We tested quietly, privately, with a doctor Christopher trusted. The wait was the longest I have ever done. Even knowing the first clinic’s results, even feeling the history of it in my bones, I woke at three every morning and thought: What if I am wrong about everything a second time?

The call came on a Wednesday that smelled like rain. “Grace,” Christopher said gently, “the tests are conclusive. Ryan is biologically yours. Jacob is biologically Monica’s.”

The grief that ripped through me then wasn’t the grief of loss. It was the grief of sudden, permanent truth. I slid down the kitchen cabinet to the floor and cried the way you do when your body decides there is nothing else useful to be done. After a while I crawled to the mantle and took Jacob’s kindergarten picture into my lap and said aloud to the boy with the missing front tooth: “You are not the sum of this paperwork. You are my whole life.”

Thomas took the results as absolution—from him, of him, for him. He slept elsewhere, then left elsewhere, then sent an envelope by courier with a crisp petition and a signature that looked relieved. In the margins of our bank account I found charges that made a story: a bouquet of roses never delivered to our door, a dinner at a restaurant where the napkins are real linen, a hotel on the edge of town with reviews praising discretion. I waited with the photographs Christopher printed out of the credit card statements until he came home and then asked quietly, “Who did you buy the flowers for?”

“Don’t start,” he said, but I did, because at some point starting is the only ethical choice. He shrugged and said, “It doesn’t mean anything,” and I hit him once, flat-palmed, a sound that startled me as much as it did him. It wasn’t the right thing. It was the true thing at the time. He left and didn’t come back for three nights. On the fourth he hired a man to tell me we were done.

Part Two

The park where we met Monica and Ryan was the kind of municipal attempt at peace that works most days—river, path, benches donated in memory of someone. The winter was trying to give way; the trees were all gestures and no leaves. Jacob walked beside me with his hood up, his shoulders hunched the way boys fold in on themselves when they think someone has stolen something that belongs to them and they can’t figure out what.

Monica stood with her hands wrapped around a paper cup, steam curling into the cold. Ryan shifted next to her, teenage boy written all over him in restless energy and defiant stance. We didn’t hug. We didn’t shake hands. We stood on a patch of smashed gravel and tried to build a bridge out of words.

“Jacob,” I said softly, crouching to his level because I had read once that your eyes should be where their eyes are when you ask them to see something hard, “the hospital made a mistake the night you were born. A terrible one. It doesn’t change who you are to me. It doesn’t change one second of our life together. You are my son.”

He flinched like the word hurt. “So I’m not yours,” he said, not a question. “Not Dad’s.” He looked at Ryan without looking, and then at his shoes. “Then who am I?”

A mother’s job is to answer questions, to dry tears, to fill plates, to know things. For the first time in his life, I didn’t have the kind of words that ease. “You are mine,” I repeated. “Because I have loved you every day. Because I know the sound of your laugh and the way your eyes backlight when you talk about planets and how you hate lima beans and that you pretend you don’t cry at movies but you do. That is who you are. My son.”

He looked away. It was not enough. Sometimes love is not a balm. Sometimes it is a thread you have to hold while the person on the other end decides whether to pick it up. We talked logistics—tests, records, therapy because none of us would move through this whole. We set small, manageable promises: we would meet at the park again; we would let the boys set the pace with each other; we would not force a word neither of them was ready for.

In all my rehearsals of this conversation over the past days, I had never once considered what it would feel like to stand in front of a boy who was mine by blood and not know how to reach for him. Ryan spent most of the conversation pretending to text. When Monica called him “honey,” he shrugged her off with the casual cruelty of adolescents. He glanced at me twice. The first time, a flicker—surprise maybe; the second time, something that looked both like curiosity and resentment. I wanted to kiss his forehead and tell him I had not chosen any of this. I wanted to give him back his own life. There was no tidy way through.

At home later, Jacob locked his bedroom door. I sat on the floor outside it and said the only truth big enough to fit through wood: “I love you. I’ll be here when you want me.” Two nights later, he came and sat beside me on the porch steps without looking at me.

“If I’m not your son by blood,” he murmured into his knees, “then what am I?”

“You are my son,” I said, “in all the ways that matter. You are also something else now, and we will learn together what to call that. Both can be true at once.” We sat until the cold made our fingers ache and then went inside and watched a dumb movie and laughed in the wrong places and later, when I turned off the light, I heard his door open and felt a weight lean against me for three full breaths before sliding away.

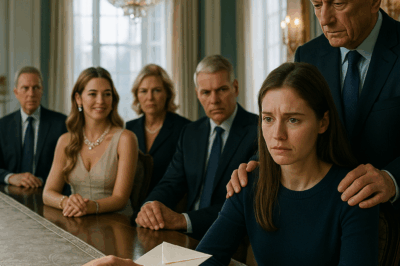

Christopher filed suit against the hospital on a tight stack of grounds I learned the definitions of and then promptly forgot. Driving to the courthouse on the day of the hearing, I felt like I was walking into a cathedral and a boxing ring at once: awe, dread, the sense of other people’s stories leaking into yours through the air conditioning vents. The hospital’s lawyer wore a suit that cost more than my car and a smile that didn’t reach his eyes. Diana Whitmore took the stand with quiet dignity and said the thing that broke the room open: “We failed these families.” Natalie testified too, voice breaking on the line where she said, “I thought I could fix it later. I was wrong.”

No gavel fell with finality. This isn’t television. The judge’s ruling came two weeks later and sounded like a complicated apology: damages to cover therapy and the cost of whatever the boys would need to not be broken by this hard truth, an order to overhaul the hospital’s neonatal procedures, a public record that said what had happened was not a rumor or a game of telephone. When the papers arrived, I didn’t smile. But I exhaled. It is something to have the world say your pain is not imaginary.

Thomas did not attend. Of course he didn’t. He sent a text the afternoon we were scheduled to stand up and be counted: Don’t drag my name into this. I wrote back one word: Done. I had been dragging his name for fifteen years; I was done with that too.

The boys found each other in increments. The second time at the park, they threw a basketball back and forth for ten minutes without speaking and then, in a burst of frustrated laughter that made both Monica and me flinch in gratitude, they started arguing about the result of a foul neither of them had committed. The third time they swapped playlists and rolled their eyes at everything on each other’s lists. The fourth time, Jacob came home and asked if we had any pictures of me at fifteen. He looked for himself in my face and then looked away and then looked again, which is how looking works when you are trying not to need it.

We built new rituals. Tuesday dinners at our house with Monica and Ryan and a lot of awkward silences covered in garlic bread. Saturday mornings shooting hoops in the driveway while my mother yelled fouls from the window in a sweater she refused to retire. Family therapy on Thursdays where a woman with kind eyes and an ability to sit with discomfort longer than anyone else in the room taught us vocabulary for things you usually only point at: grief, loyalty, rage, relief, belonging.

In late spring, with the dogwoods out and the air full of pollen and promise, Jacob stood in the doorway while I chopped onions and said, “Mom?” like the word had splinters in it.

“Yes?”

“Do you think I could call Monica sometimes? When I feel weird. Not instead of you. Just also.”

I put down the knife and wiped my hands and pulled him into me like he was three and had skinned his knee. “Yes,” I said into his shoulder. “Yes, you can.” When he pulled away, his eyes were wet and he wasn’t ashamed of them. “I’m still yours,” he said, a statement not a question. “Always,” I said.

We invited Monica to Mother’s Day brunch. She brought a salad and a potted plant and a card that said in careful, printed letters, Thank you for sharing your heart and your son. I wrote one for her that said, Thank you for sharing yours and for looking at mine with kindness. We did not try to name each other. We did not need to. We sat with our shared and separate grief and watched the boys steal strawberries and almost-fight with their elbows.

On a warm June evening, the four of us—me, Jacob, Monica, and Ryan—stood outside the high school auditorium. The banners flapped. The air smelled like sweat and popcorn and hairspray. The boys were in shirts they let us iron and shoes they did not want to wear. They had performed in a small music showcase—Jacob with his trumpet, Ryan with his guitar. They had nodded at each other onstage when their parts overlapped and then avoided eye contact in the lobby in a way both mothers recognized as deep tenderness disguised as teenage indifference.

“Pizza?” I proposed, and for the first time they both said yes at the same time.

Later, at home, with the kitchen light off and the porch lit softly, I watched them from the steps while they argued in low voices about chords and tempo. Monica sat beside me. We didn’t have to talk about everything to talk about something that felt like everything. “It’s strange,” she said after a while, “to love a boy who wasn’t born from you and also miss a boy you didn’t know was yours.”

“Strange,” I agreed, “and possible.”

“It’s a kind of miracle,” she added, “that they’re both ours now, in the ways that matter.” We listened to the boys laugh at a joke neither of us could hear and both of us pretended we understood.

The lawsuit settled. The headlines moved on. The hospital implemented ankle tags and triple-check protocols and a rule about overnights that meant no twenty-one-year-old would ever again cry at a flower shop over a mistake made with good intentions and bad support. Thomas moved states. He sends Jacob texts occasionally; sometimes Jacob answers and sometimes he doesn’t. That is theirs to navigate. I don’t build maps where I don’t have the terrain.

One afternoon in late summer, I found the four of them—my mother, Monica, the boys—on the driveway drawing a chalk court for a three-on-one that immediately devolved into arguments about lines and laughter about nothing. I stood at the screen door and watched until Daniel’s hand slid around my waist and his chin found that place on my shoulder that makes everything in me go quiet.

“Court day tomorrow,” he said softly. He meant the hearing where a judge would attach legal words to a reality we had already been living: joint custody in a way the law could write down, visitation schedules that respected teenagers’ lives, the hospital’s formal apology entered into the record. He would be there because that is what he does. He shows up.

“Do you ever feel like we are making this up as we go?” I asked.

“We are,” he said cheerfully. “But we’re very good at it.”

The courthouse the next morning was brighter than the first time. Some combination of sun and relief and the way people say your name with kindness when they have seen you three times in one season and watched you not combust. The judge read the agreement. Words like “acknowledge” and “recognize” and “affirm” landed with the weight of something older and steadier than a blood test. When the gavel fell, it sounded like a punctuation mark you choose, not one that is forced on you: period, not exclamation point.

Outside on the steps, reporters smiled politely and decided we were not scandalous enough to bother. Monica hugged me the kind of hug that confirms a promise, and we both laughed because it felt ridiculous and right to be giddy at a courthouse. The boys rolled their eyes and then, in a move that would never be repeated, allowed photographs. My mother dabbed at her eyes and Daniel pretended to cough instead of cry.

We went for pancakes. Jacob ordered chocolate chip with extra chips; Ryan said that was an abomination and ordered blueberry; they split both plates after ten minutes. Monica and I shared coffee and quiet, which tastes better than any syrup.

I won’t tell you that everything is easy now. Some nights Jacob still sits on the porch with his hood up, and I sit beside him and do not fill the silence. Some days Ryan is moody and mean in the way adolescents punish people who love them because they can. Some mornings, I still wake at three and need to touch the doorframe to remember the house is holding. But ease wasn’t the point. Truth was. Family is.

That night, late, when the house had tucked itself around us, I walked out to the yard. The porch light hummed. The cicadas did their endless metallic prayer. The boys had drawn a dumb smiley face in the chalk court earlier, and the way the mouth curved made me laugh. Daniel came out and put a blanket around my shoulders because he is the kind of man who thinks ahead and thinks around corners and thinks of the person beside him first.

“Do you ever miss the life you thought you were building?” he asked, not unkindly.

“Sometimes,” I said, honest because lying defeats the purpose of surviving. “But not today.”

Across the street, a house’s television flickered blue through curtains. Somewhere, a dog barked and was answered by another. The air smelled like cut grass and the promise of rain. In the living room, my mother left a lamp on out of habit and love. In two rooms, two boys slept under ceilings we had learned to love without owning the sky.

I used to think a DNA test could destroy a life. I don’t believe that anymore. It can destroy lies. It can destroy the false sense that control is the same thing as love. But life—the stubborn, ordinary kind that looks like breakfast and homework and ironing shirts for choir concerts—refuses to be destroyed. It makes room. It heals around the imperfection. It chooses.

Tomorrow will be school drop-offs and court forms and a phone call with Diana about a new hospital policy she wanted me to see. It will be reminding Jacob to take his trumpet and Ryan not to forget the thing he inevitably forgets. It will be kisses and sighs and soft fights about cereal. It will be the life we get because we did not let the worst moment decide the rest.

I whispered to the dark, not a prayer exactly, more of a promise: “I am still a mother.” And the night, generous for once, seemed to nod.

END!

News

One Small Request—Pretend to Be His Fiancée—But the Ending Brought Me to Tears… CH2

One Small Request—Pretend to Be His Fiancée—But the Ending Brought Me to Tears… Part One The dog trembled in…

My husband hit me after his mother spoke, but what he saw next shattered him completely… CH2

My husband hit me after his mother spoke, but what he saw next shattered him completely… Part One It…

Rushing to My Fiancé’s Mansion, I Defended a Helpless Stranger… and What I Discovered Shocked Me. CH2

Rushing to My Fiancé’s Mansion, I Defended a Helpless Stranger… and What I Discovered Shocked Me Part One I didn’t…

My Parents Told My 7-Year-Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off. CH2

My Parents Told My 7‑Year‑Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off Part…

My parents gave $10 million to my sister and told me to earn my own money! then grandpa gave me…

My parents gave $10 million to my sister and told me to earn my own money! then grandpa gave me……

I Tested My Husband by Saying “I Got Fired!” — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything. CH2

I Tested My Husband by Saying “I Got Fired!” — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load