At Family Dinner, I Accidentally Saw My Mother And Sister Using My Fake Signature

Part One

My name’s Veronica. I’m thirty-two, and I never expected a simple family dinner in our Irvine home to feel like walking straight into an ambush. I make my living as a marketing specialist — a job that trains you to spot manipulation in copy, in client presentations, and in the little tells people give off when they’re not telling the whole truth. I could pick apart ads for a living, but nothing in any campaign deck ever prepared me for what I saw the night my grandmother passed away and her inheritance turned the people I loved into strangers who looked like strangers and acted like conspirators.

Pamela — Grandma Pam to anyone who adored her — had been my secret compass since I was a child. While other kids chased Saturday cartoons, I sat across the diner booth from her, legs barely reaching the seat, while she taught me the art of making money make sense. She used to divide a pizza into five metaphors: essentials, savings, help for others, small pleasure, and future plans. “Build security by thinking ahead,” she’d say, fingers annotated with flour from the pastry she loved. She showed me how to track every dollar in a tiny ledger and how compound interest felt like magic when you were twelve and felt powerless in an adult world.

I learned to love thrift as a creative act. At sixteen I opened my first investment account with babysitting cash. At twenty-two I walked into a state university with a gym bag, a scholarship, and two part-time jobs. I spent my twenties building a modest life in Irvine: a marketing internship, a string of promotions, an apartment that became mine after years of saving, a condo paid off slowly and without drama. While Sabrina, my sister, evaporated money like it was perfume — designer bags, impulsive vacations, a luxury SUV that looked a size too big for the neighborhood — Mom and Dad thrived on enabling. They folded themselves into her life like supportive stagehands, offering bailouts with a smile and a shrug.

You have to picture that family dynamic to understand why Pamela’s decision felt like a sun moving behind clouds. When the diagnosis came — a swift, merciless stage-four cancer — I moved in bursts: work calls in the early morning; hospital waiting rooms; chemo schedules typed into a calendar I starred on my phone. Pamela was lucid on most days, and on one quiet evening, with the salt-sour tang of hospital coffee on the table between us, she called Mr. Sutton, the attorney she trusted, to the apartment. She drew a blueprint with measured hands: an irrevocable trust, assets shielded, protections that would ensure her life’s careful thrift didn’t evaporate into a pattern she’d watched my parents repeat for years.

“Trevor and Cheryl enable,” she said, tapping the table. “I’ve watched it for decades. I don’t want animosity at my funeral and a mess afterward. Veronica, you will be responsible, and you will be careful because you are, for reasons I’ve always loved, cautious. You’ll honor this the way I want.”

The trust made me the sole beneficiary, yes, but it also staggered my conscience. Aunt Cheryl witnessed, the notary signed, and Pamela blinked, smiled, and slept. It felt like a private victory: the careful woman who had taught me how to budget had used her last months to safeguard the small dry particle of dignity that finances can be. After the funeral, there was a period of muted family rituals; people send casseroles, they weep at eulogies, they pretend the brittle things were not said five minutes before. Life does not absolve itself.

Then the text came.

Family dinner. Friday. Important. Dad signed it off with a formality that felt wrong on its face. We never scheduled family dinners like a board meeting. My instinct lit up like a warning beacon. That week I drove through Irvine’s neighborhood with the knowledge of what could happen pulsing in my chest: opportunists rearrange, the entitled assume, and the enabling make arrangements as if they were acts of love.

It was worse than I expected.

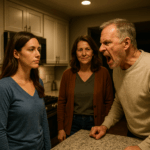

Sabrina’s new SUV shone under the streetlight when I pulled into the drive. Mom, all too bright with lasagna as a decoy, ushered me in with the practiced hands of someone who has hosted too many apologies behind food. Dad offered a clipped nod — I read him like a client who’s prepping for a negotiation. In the living room, I noticed a stack of documents on the side table before anyone could redirect me with small talk and bread bowls. A heading I knew too well — trust fund paperwork — and, beneath it, a signature that I recognized by myself the way you can recognize handwriting that has traced your childhood: my name, but crabbed and wrong, obviously forged.

The sight came in a slow-motion, nausea-inducing moment. I could see my name and the crooked letters that tried to imitate me. I felt my throat grow dry. Instead of collapsing, I did what marketing people often do: I observed and logged. I smiled and let them steer the conversation toward my so-called extra money, toward how “generous” it would be to redirect it. I let them think I hadn’t seen. That little white lie — the one where I stopped the public scene from exploding — was tactical, like sliding a card down to the ace.

They had rehearsed a narrative in the kitchen, perhaps in whispers over the phone. The plan, crudely: forge the signature, push the papers through, and act like good family on the night of sorrow. But we had learned to be cautious; Mr. Sutton had set up red alerts, monitoring suspicious access to the trust accounts. He’d done it the only way the law could often be trusted — by anticipating who in a family might act without honor and by installing technical barriers. There was a $1 trick in the trust too: Pamela had funneled some assets in a way that looked lucrative on paper but was actually wrapped in legal protections. It was not wealth that could be easily stolen, but it could be used as bait to expose who would try.

When I excused myself the first time to the bathroom, I detoured to Dad’s home office down the hall. If you want to eavesdrop in a family, the first stop is always where the papers live. On his desk lay a folder labeled “Sabrina’s Finances” in his neat, utilitarian handwriting. I stepped behind the door, felt my pulse in my throat, and leafed through. There it was: records of bailouts, unpaid loans masked as “family support,” screenshots from Sabrina’s social media with lavish trips that were not matched by bank statements, and an email from her ex Scott referencing overspending. The evidence painted a pattern as clear as a graph. The more I read, the less surprised I was that the forgery existed. The problem was never Sabrina’s spending; it was the enabling that made it an addiction.

In the dining room their faces were the ones you reserve for holidays where you are expected to be polite. Dad cleared his throat like a man at a press conference. “We’ve been thinking about Pamela’s estate,” he said, and they all spoke in that soft, corporate tone people reserve for stirring hurt into logic. “Sabrina’s in a tight spot financially, and since you’re stable, Veronica, it makes sense to redirect some of that inheritance her way.”

They weren’t asking. That was the first thing. The second was the number: $250,000. A round, stupidly precise figure that might have paid a down payment on a new condo or cleared a list of unpaid cards. I leaned in and asked, voice even, to get specifics. They dropped anecdotes: investments that went south, bills that piled, and the gentle, constant rhetoric of “family helps family.” If only family had kept a ledger like mine, we might have been spared this entire night.

I had a plan. See, witnessing a forgery is one thing; proving it and turning what could be gaslit into a document trail is another. Before I’d stormed in, I had called Aunt Cheryl and whispered: be ready. She’d answered my call with the rare kind of quiet solidarity older relatives sometimes reserve for a younger person whose bones look like themselves. Mr. Sutton had been prepped. I had my phone clicking photos of paper in the hall, of signatures, of my parents’ emails. I had texts with friends who would corroborate timelines.

And then — as if on cue — my banking app pinged with a red alert. Unauthorized access attempt detected. Mr. Sutton’s watchful technology had flagged a movement toward the trust. I held my phone up like an exhibit in a courtroom where the jury was my family. “See this?” I said, and the sound of my phone’s alarm beat against the polite clink of silverware as if the room itself realized the farce had been uncovered.

Mom gasped. Sabrina made a move for my phone, but I withdrew it like a lawyer protecting evidence. Dad’s face drained — the man who had always relied on optimism was suddenly old and exposed. They tried the emotional pile-on — “You’re selfish,” “You would deprive your sister,” “Pamela would have wanted us to help” — but I had documents. I had Scott’s email. I had bank screenshots. I had Aunt Cheryl corroborating the trust and Mr. Sutton’s notarized signatures. In a week, they filed suit to contest the trust’s validity, but the legal world isn’t kind to forgeries and the law in California gives weight to the intent and proof present when an irrevocable trust is formed correctly.

The lawsuit they filed was theatrically framed as a noble defense of family rights: claims of undue influence, diminished capacity, faint-hearted pleas that Pamela had been confused. They hired a probate attorney with the smooth suit and the assured talk. Mr. Sutton, however, had been meticulous. Medical records affirmed Pamela’s clarity the day she signed. Aunt Cheryl had been present and would swear it in front of any judge. The timestamps on the paperwork made a clean chronological chain. Under California probate law, an irrevocable trust properly executed is not easily undone. The judge sifted through the affidavits, the evidence, and the emotional pleas and ruled swiftly: the trust stood.

That ruling birthed a cascade of consequences that I confess I had not entirely anticipated emotionally. Viewed through my childhood memory, my parents had been wronged by their own indulgence. In their attempt to fix a problem that had never been mine, they had created a legal scandal that would take everything. Creditors smelled the weak link. Sabrina’s debts, which had been papered over with loans and generous gifts, were suddenly visible to people who wanted repayment and had the legal muscle to seize assets. My parents had co-signed, backed, and guaranteed without calculation. Bankruptcy filings followed as the household attempt to reconstitute their lives collided with financial reality.

They suffered. The house we’d all grown up in — the familiar bones of our lives — was sold to meet liens, and the family unit collapsed into legal affidavits and cold letters. Sabrina’s designer watch was reclaimed by a pawn broker, and the shiny SUV disappeared in a repo truck at dawn like a painful metaphor for the things people assume are permanent. A quiet social ostracism followed. People I had known since elementary school found themselves shifting allegiances. Some sympathized with my parents in whispered condolences; others, quietly aware of the bailouts and the years of enabling, drifted away. Cousin Dustin emailed me after months of silence: “I’m done enabling. I’ll help you legally.” Aunt Cheryl took my hand in public, as if to say: We did what we had to.

I did not gloat. I would not claim joy in the fall of my family’s financial empire. What I felt in the months that followed was a complicated mix: grief at what had been lost, relief at the legal vindication of Pamela’s plan, and a bitter clarity about who loved me for my choices and who loved me because it was convenient. I cut off contact with the phones on both ends — the rage-laced texts, the pleas masked as concern, all routed through Mr. Sutton when necessary. Therapy helped me hold my standing without collapsing into the guilt my parents weaponized.

And then I built something.

It seemed only right to honor Pamela by making her lessons live beyond the one family that had failed to hear them. I took a portion of the trust and launched the Pamela Financial Literacy Foundation. It was a small nonprofit at first — workshops at community centers, budgeting classes for teens at Irvine High, webinars about spotting manipulative family dynamics disguised as “help.” We created modules that taught young adults how to set monetary boundaries without burning bridges, how to spot when a family dynamic is exploitative, and how to negotiate money conversations with care and firmness.

People came. Teens on the edge of college came, parents who wanted to model better behavior came, and even some older adults showed up to learn how to protect their savings from predatory relatives. The work felt like a balm. I poured energy into making the curriculum humane — real scenarios, role-playing sessions, templates for tough conversations. We gave micro-grants to students who otherwise had to dip into shaky credit. We published a short guide called Keeping Money Kind that made rounds in local libraries and on campuses. Through the foundation, Pamela’s voice — no longer the private whisper in a diner booth — started to radiate outward.

The foundation also helped me form my chosen family. Jenna, my college friend, became my co-conspirator in all things good. She helped write the grant proposals, tutored me through public speaking nerves, and became the person who knew the exact balance between letting me be furious and letting me be kind. Aunt Cheryl, too, became the family that I could return to without fear of being consumed by enabling cycles. She sat with me at fundraisers, introduced me to donors, and chuckled in a way that said: We did right.

Part Two

People often imagine retribution as something dramatic and cinematic: a reveal at a party, a viral video, a courtroom diatribe that leaves a villain crumpled. In our house, consequences were quieter and longer. They were paper trails and legal maneuvers and the slow bleed of privilege washed away by reality. The bankruptcy filings, the asset liquidations, the loss of social invitations — these were consequences that left scars but also opened space for truth.

Sabrina slid away from our lives at first, punished by debt collectors and the social shame of a lifestyle that had to be unlearned quickly and without the friendliest of teachers. She tried — clumsily and sometimes in ways that showed old habits — to rebuild. Her first attempts at finding sustainable work were rocky. Employers, once enticed by the sheen of her socialite resume, were now sometimes wary of her credit history. The kind of trust required in workplaces for financial responsibility was not always given. She took temp jobs, did retail stints, and swore off the luxury life she had once thought her birthright. Embarrassment does the subtle work of changing a person if, and only if, it is accompanied by a willingness to learn.

My parents moved into a smaller rental. The house that had held our childhood — the one the neighbors used to admire — sold to pay creditors. Trevor, who had always been solid in a way that made mistakes easy to gloss over, took the bankruptcy with a stoic sadness. He worked two jobs for a while — delivering packages and consulting on lawn care he had once disdainfully considered beneath him. Cheryl, whose pearls had once seemed permanent, took provincial daytime work to make ends meet. They learned humility in the slow daily grind most people know well: the little defeats and the small repairs to character.

What surprised me was how some relationships shifted sideways into something better. Cousin Dustin, after a period of awkwardness, became a person who visited to fix things around my condo: a leaky faucet, a balky air conditioner. The awkwardness grew into genuine connection as we traded life stories instead of ledger balances. Aunt Cheryl became the living archive of family truth, the person who recited Pamela’s final words with a tenderness that had no justification other than love. I learned, in the months after the court ruled in Pam’s favor, to extend a measure of empathy without giving away my boundaries.

Sabrina’s path to contrition was not linear. Initially she denied and then negotiated. She blamed bad timing, then addictive behaviors, then social pressure. It took a year of support groups, a job in a small startup doing social media for a local bakery, and therapy before she stopped making excuses. In time she gave a small public apology — a short statement at a community event for the foundation — and then she volunteered at the center handing out pamphlets about budgeting. The crowd members who had known her before looked on with complex expressions. Some forgave because they believed people can change; others continued to hold her accountable. Accountability, I learned, is the scaffolding of healing.

The foundation grew slowly, not in the way foundations on television do, with gala galas and champagne splurges, but in secondhand moments: a student who learned to save a few percent of a part-time paycheck, a mother who wrote to tell us she finally demanded a formal repayment plan from an adult child instead of bailing them out. Those notes mattered more to me than the ownership of anything. Money without mission can be a dull thing. Pamela had always believed the purpose of savings was to preserve dignity — and I felt like we were living that truth.

As for the legal aftermath, there were still snarled tangles. My parents’ bankruptcy discharge blurred into a fog of consequences: credit repair took years; opportunities came less easy. They wrote letters to me in the early months that read like attempts at apology and explanation: “We were trying to help.” But the letters also sounded like the old reasons that had allowed the enabling in the first place. For a while I read them and burned them in the sink and then stopped. After therapy I allowed some of them back into my life under the condition of a new rule: any communication had to be channeled through Aunt Cheryl or Mr. Sutton. Boundaries are not walls, as I had told them during the first arguable night; they are frameworks for functional relationships.

Time, the slow, impartial arbiter, rearranged distances. There were holidays where my table seat was conspicuously blank. There were others where, with awkward grace and small apologies, people showed up. I did not reconcile in a grand gesture. Instead, reconnection happened in coffee meetings where my parents learned to ask about my work and did not assume I would proffer funds; where Sabrina showed up to volunteer for a foundation workshop and, in front of a room, admitted that she had once been the person who thought money was a way to fix feelings. I listened, took her hand, and told her that apology is a beginning; repair is the labor that follows.

As the foundation matured, its projects matured too. We ran a mentorship program pairing young adults with retired financial counselors who volunteered their time. We launched “Money & Boundaries,” a course for college freshmen that taught the difference between family support and family sabotage. We got a small grant from a community bank to build an app for expense-sharing that included legal templates for agreements between family members — a tool I always wished my younger self had. The accomplishments were small and steady and meaningful.

There were darker nights, too. I would sometimes wake in the middle of the night and hear my mother’s voice sing past love — a sound from another life — and wonder if I had been cruel not to open the door to her pleas earlier. Therapy taught me to hold those doubts like weather: passing phenomena, not verdicts. I would write letters I never sent and sit with them until the ache loosened. Jenna sat beside me in those moments like a lighthouse. She reminded me that choosing peace is not the same as choosing cruelty. It is choosing survival.

Over time I learned the geography of forgiveness. It’s not a single destination; it’s a landscape you navigate with maps made of boundaries and tools of accountability. I forgave because I no longer wanted to carry around rancid resentment; I made a point not to forget because forgetting is often what helps people repeat mistakes. I took steps to educate myself and others about manipulative family dynamics: what to watch for, how to set up contractual protections, and how to create contingency plans that are not shameful but practical.

A year and a half after the dinner, the foundation hosted a modest conference on financial empowerment at the local community center. People came — young couples, single parents, retirees who wanted to ensure they were not coerced into gifts they could not afford. I gave a talk about building safety without vengefulness, about how Pamela’s trust was not about punishment but about preserving a dignity that she feared would be preyed upon. Afterward, an elderly man approached me, his hand trembling. “My sister always took advantage of me,” he said. “I finally found a way to say no.” He hugged me that way strangers occasionally do when thanks are long overdue. That moment felt like an exhale that reached into the chamber of everything I’d been building.

Sabrina showed up at that event, not in a designer dress but in a t-shirt that said “Community Helps.” She distributed pamphlets and apologized in ways that were not loud. It is easy to perform humility; it is harder to show up in small, consistent acts. She did. Her presence did not erase past hurt, but it meant she was trying to learn how to be part of a different story.

My parents returned one afternoon, older and quieter. Dad’s hair had gone whiter from all that worry. Mom apologized with an honesty that was new. “We were wrong,” she said, “and we didn’t understand the damage we were doing.” The apology was simple and late and honest. I did not cancel the loss; I accepted the apology as one of the many small repairs that get you through a lifetime.

Now, when I walk the familiar Irvine streets with Jenna or sit in the community center before a workshop and watch the crowd arrive, I remember Pamela’s small lessons — her pizza slices and her thrift — and realize how deftly they shaped my life. Pamela had not merely left money; she had left a system for rescue. She’d used the law and the trust like a kindly, stubborn guardian. She had expected me to be quiet and sensible; she had never expected me to become a defender in a way that courtroom rules and nonprofit filings demanded.

The end of this story is not a dramatic scene with a closing bell. There are no sudden reconciliations that erase decades of behavior. What exists instead is a set of steady, human outcomes. The trust stood. The family, for a while, fractured and then recalibrated. Sabrina learned, slowly, how to push against impulses that had once felt like identity. My parents lost a house but gained a clarity they had not had before. Pamela’s legacy lives on through the foundation, helping others avoid the same kinds of petty tragedies where love is conflated with permission to exploit.

Ethics are not something you can sign onto in an evening and expect to sit comfortably with for the rest of your life. They are choices repeated daily. My choice was to protect what Pamela and I knew to be sacred: the right to a life that is not hollowed out by those who love you. In protecting it, I lost some things and gained others. I missed dinners with the parents who had raised me and watched their private descent with an ache that time would not immediately soothe. I gained an audience that listened and in that listening found a life mission.

On Sunday afternoons, when the sky is clear over Irvine and the lemon trees in the neighbor’s yard bloom, I call Aunt Cheryl and Jenna to arrange the workshops for the coming month. We talk about the small victories: the student who saved three hundred dollars, the woman who finally set a repayment schedule with her son, the elder who kept his deed because he had documents in place. The victories are small, and they accumulate.

If I had to capture the moral of all this in one sentence — and I know people want morals — it would be this: protect yourself with kindness, and teach others to do the same. When your family betrays you, it breaks you open — but the light that seeps in can grow something better if you let it. This is the life Pamela left me: practical tools, a legal safety net, and the courage to refuse to be a puppet.

And some nights, when I am alone and the house is quiet, I pull out the old ledger I’d kept since I was twelve. The pages are yellowing, and the handwriting is still the same — small, precise, hopeful. I trace the columns with a finger and think of a woman who taught me to budget not only money but dignity. In the end, that was the inheritance I protected.

Part Three

The letter arrived on a Tuesday morning, the kind of California day that made everything look calmer than it really was. The air outside the foundation office smelled like jasmine and exhaust, and the sky over Irvine was an obnoxious, cloudless blue. I was balancing a to-go coffee in one hand, my laptop bag on my shoulder, and a stack of printouts for our “Money & Boundaries” workshop when I saw the envelope on my desk.

Certified mail. County seal. Return address: Orange County Probate Court.

My stomach did the same slow roll it had done the night of that family dinner, when I’d seen my forged signature sitting on my parents’ side table. I didn’t even sit down. I just slid a finger under the flap and unfolded the legal-sized pages.

It was all there in the official language that always pretends to be neutral. A complaint had been filed with the probate court’s elder-abuse review unit, requesting an inquiry into Pamela Sutton’s irrevocable trust. Allegations: undue influence by me, Veronica Davis. Questions raised about Pam’s mental capacity at the time she signed. Suspicion that I had “coerced” her into disinheriting my parents and sister.

I read the words twice and felt something hot crawl up the back of my neck. I’d already lived this. We had a judge’s decision on the trust, medical records, witness statements. We had the truth. Pamela had been so painfully clear-headed that day it hurt to remember. Yet here it was again, resurrected like a bad sequel.

There was one line that made my fingers tighten around the paper: “Anonymous complainant states that the decedent’s true wishes, as expressed to her family, were altered by her granddaughter’s financial agenda.”

Anonymous, my ass.

I called Mr. Sutton before I even took off my coat.

He picked up on the second ring, his voice that familiar mix of dry and steady. “Veronica. I was expecting your call.”

“So you got it too,” I said.

“I did. Don’t panic yet.” Papers rustled on his end. “The court is obligated to open an inquiry if someone files a complaint with the right buzzwords. This isn’t a redo of the lawsuit; this is a review for elder abuse. Different angle, same story.”

“It says anonymous,” I said. “Do you think—”

“I think we should not guess until we have to,” he cut in gently. “I’ll file a response. We’ll provide the records again. You may have to sit for a brief interview with an investigator.”

I sat down hard in my chair. The office around me hummed with normal sounds—printers, the low murmur of volunteers in the next room, the clink of someone’s mug—but inside I was back at that dinner table, phone screen glowing with a fraud alert, my parents’ faces caught between defiance and terror.

“I can’t do this again,” I whispered, before catching myself. “No. I can. I just don’t want to.”

“You already did the hard part once,” Sutton said. “This is mop-up. Annoying, but manageable. Come by this afternoon?”

“Yeah,” I said. “I’ll be there.”

When I hung up, Jenna was standing in my doorway, leaning against the frame, hands in the pockets of her wide-leg pants. She must have read the expression on my face before I could hide it.

“Bad kind of mail?” she asked.

“Probate court,” I said. “Apparently someone thinks we didn’t get enough drama the first time.”

She crossed the room in three long strides and swung a chair around to sit facing me, elbows on the backrest. It was one of the things I loved about her—no hovering, no empty cooing. Just a solid presence.

“Walk me through it,” she said.

I summarized the complaint, the allegation of undue influence, the threat of an elder-abuse inquiry. Saying it out loud made my jaw clench. Pamela had been the sharpest mind in any room right up until the week her body gave out. To suggest she’d been confused was an insult that scratched at old grief.

“Do you think it’s your parents?” Jenna asked.

“I don’t know,” I said, though the names lining up in my head were familiar. “The lawsuit failed, and the bankruptcy finished. They’ve spent the last couple years trying to stitch their lives back together. I want to believe they’re done fighting Pam’s ghost.”

“What about Sabrina?”

I pictured my sister in her “Community Helps” t-shirt, handing out pamphlets, staying late to stack chairs. She’d shown up, consistently, at our workshops. She’d started giving a tiny talk about credit cards and emotional spending, and people listened. I’d seen the way her hands shook the first time she admitted in public that she’d once treated money like anesthesia.

“I don’t think it’s her,” I said slowly. “She’s too busy actually trying to earn people’s trust for once.”

“So someone else with an opinion and a grudge,” Jenna said.

“Extended family is a bingo card of both,” I muttered.

Jenna reached over and tapped the letter with one finger. “Whatever this is, you’re not facing it alone this time. You’ve got a whole foundation behind you now. Volunteers, board members, a pile of boring, beautiful documentation. And me. And Aunt Cheryl. Remember her?”

At the mention of Aunt Cheryl, something eased in my chest. Pamela’s younger sister had become the emotional spine I leaned on when my own parents had collapsed into their choices. She’d been at every critical moment: the hospital signing, the court case, the first workshop we ever ran in the community center. If anyone knew where the bodies were buried—metaphorically speaking—it was her.

“I’ll call her after Sutton,” I said.

“Good,” Jenna replied. “And in the meantime, I’ll reschedule you for the podcast recording this afternoon. The world can survive one less episode of you explaining how compounding interest works.”

I cracked a small smile despite the churn in my gut. “Blasphemy.”

She bumped her shoulder against mine, then stood. “We’ve got teenagers coming in thirty minutes to learn how not to blow their summer job money. Want to teach rage-saving 101, or should I?”

“I’ll do it,” I said, surprising myself. “I need to remember why any of this matters.”

The teens filtered in a little later—hoodies, cracked phone screens, backpacks that looked too heavy for their shoulders. I told them about sixteen-year-old me and Grandma Pam’s pizza metaphor; I watched their expressions shift from boredom to curiosity when I showed them how three dollars a week could turn into something real over years. They laughed at my story about declining my first credit card in the campus quad, at the guy who’d promised me “adult freedom” with an APR that would have eaten my stipend alive.

For an hour, I was just Veronica the educator, not Veronica the alleged manipulator in a complaint. It didn’t erase the letter, but it drew a thin line of perspective around it.

That afternoon, Sutton’s office smelled like it always did: coffee, old paper, and the faint trace of lemon cleaner. He sat me down across from his desk—the same one that had held Pamela’s trust in a neat folder years ago.

He slid a copy of the complaint toward me. “It doesn’t say much,” he said. “The court will send an investigator to verify that all proper steps were followed when the trust was executed. We have medical records from the oncology team, the notary log, the audio note Pam recorded that night. It’s annoying, but we’re well-positioned.”

I pointed to the anonymous line. “Can we find out who filed this?”

“Eventually,” he said. “If the investigator decides the complaint has enough basis to proceed beyond a cursory review, there may be a hearing. At that point, we can request the complainant’s identity. For now—” He spread his hands. “We wait, we respond, we stay calm.”

“Is there any chance they overturn it?” I asked. I hated how small my voice sounded.

“If I thought that, I would have been in your car before you could dial my number,” he said dryly. “The law is on your side. So is the evidence. The only real risk here is emotional: getting dragged back into a story you thought had ended.”

That, I thought, was risk enough.

On the drive home, I watched the perfectly manicured medians of Irvine glide past—palms in exact rows, HOA-approved shrubs trimmed to compliance. The city had always prided itself on predictability, on rules that kept everything neat. My family had never fit that neatness, not really. We’d just been better at hiding the mess.

Aunt Cheryl answered my call on the second ring.

“Hi, sweetheart,” she said. “I was just thinking about you. The lemon tree’s blooming again. Pam used to say that meant money was coming, but maybe she just liked the smell.”

I told her about the complaint, the investigation. There was a sharp inhale, then silence.

“I should have expected this,” she sighed. “I heard some rumblings at the last miserable cousin barbecue.”

“Rumblings?” I repeated.

“You remember Ray,” she said. “Your grandfather’s brother’s son. The one who always said he’d retire at fifty and live off ‘smart moves’ that no one ever saw on paper?”

Unfortunately, I did. He’d shown up at Pamela’s funeral in a watch I suspected was counterfeit and a suit that wasn’t.

“He’d been talking,” Aunt Cheryl continued. “About how ‘messed up’ it was that Pam didn’t leave anything to her ‘real heirs.’ Kept using that phrase. I told him she did leave it to her real heir. He didn’t like that.”

“Do you think it’s him?” I asked.

“I think Ray has always believed that everyone else’s money is half his,” she said bluntly. “I also think someone’s been prodding your parents again. Your mother forwarded me a long text from him months ago about ‘legal options’ and ‘never too late to challenge.’ I told her, very clearly, that she needed to move on.”

I pressed my fingers to my temples. “So we might be dealing with a side-branch idiot supported by main-branch regret.”

“That would be my guess,” she said. “Trevor’s pride got hurt. Ray is a professional hurt-pride amplifier. He probably filled a form online and thinks he’s a crusader now.”

The idea that my mother might have forwarded Ray’s texts to Aunt Cheryl and not to me hurt more than it should have. It was one more proof that she still reached for consolation in the direction of people who made things worse.

“I’ll talk to her,” Aunt Cheryl added quickly, as if she heard the shift in my breathing. “But Veronica, listen to me: this doesn’t change who Pam was, what she wanted, or what you did. Paper can be thrown around; truth doesn’t move as easy.”

“Try telling that to my adrenal glands,” I said with a weak laugh.

“Get some sleep tonight,” she said. “Tomorrow, if you like, I’ll come sit with you when the investigator calls.”

“Thanks,” I said. “I might take you up on that.”

That night, I lay awake listening to the hum of my air conditioner and the occasional car on the street below. In my mind, the past replayed in jagged clips: the fake curve of my forgery on those trust papers at the dining table, Mom’s bright hostess smile thinning out, Sabrina’s sharp “You’re selfish!” as if she couldn’t hear the irony. The whine of the repo truck at dawn months later. The look on my father’s face when the judge ruled against them.

And under all of it, Pamela’s voice in the hospital room, soft but resolute: “Build security by thinking ahead.”

I had done that. I’d also built walls—some necessary, some maybe taller than they had to be. As the ceiling fan teased at the warm air, I wondered if this new complaint was just one more consequence of a family that had never learned how to accept “no” as anything but a challenge.

What I didn’t know as I finally drifted into a restless sleep was that this investigation would do something I hadn’t managed in years. It would drag every player in that dinner-table drama back into the same room—not to fight over money this time, but to decide what kind of people we were going to be now that the first disaster had settled into history.

Part Four

The investigator’s name was Elena Lopez, and she did not look like a villain sent by fate. She looked like a tired public servant who had seen too many families eat each other over bank accounts they barely understood.

We met two weeks later in a windowed conference room at Sutton’s office. Sutton sat at one end of the table, his legal pad in front of him. I sat on one side; Aunt Cheryl sat on the other, her hand resting on mine under the table. Investigator Lopez laid out a recorder, a neat folder of documents, and a stainless-steel travel mug that smelled like cheap coffee.

“Thank you for cooperating,” she said. “These reviews are usually straightforward. I’ll be asking you some questions about your grandmother’s condition when the trust was signed and about your relationship with her.”

Her tone was polite, almost bored, but her eyes were sharp. I recognized the look; I used it in focus groups, when I was trying to see through whatever story a brand wanted to tell.

She started with the facts: dates, hospital names, names of witnesses. Sutton supplied copies of everything: the trust itself, the oncologist’s letter attesting to Pamela’s capacity that day, the notary’s log. Then Lopez turned to me.

“Tell me about your grandmother,” she said.

It wasn’t the question I expected. I blinked. “Pamela was…” I paused, searching for a word bigger than the ones we usually throw around. “She was disciplined. Funny, but in this dry, precise way. She loved puzzles. She thought spreadsheets were a love language.”

A small smile tugged at Lopez’s mouth. “And your relationship with her?”

“I was… her project, I guess,” I said. “In a good way. She saw that I liked numbers and planning, and she… nurtured that. We spent Saturdays going over my little ledger. She never pushed it on my sister. She respected that we were different.”

“Did she ever express to you any resentment toward your parents or sister?” Lopez asked.

“She expressed concern,” I said carefully. “She thought my parents’ way of supporting my sister was unsustainable. She was very clear that she did not want her own savings to get sucked into that pattern.”

“And when she decided to create the trust that left everything to you,” Lopez continued, “did you suggest that arrangement, or was it her idea?”

“It was hers,” I said, feeling my spine straighten. “She called Mr. Sutton. She called Aunt Cheryl to be a witness. She explained it to me as a protection—against creditors, against the family dynamic she’d watched for years. I told her it made me uncomfortable. She said discomfort was preferable to watching her life’s work evaporate.”

Lopez nodded, jotting notes. “The complainant alleges that you isolated Pamela from other family members during her illness. Is that accurate?”

I laughed, then caught myself. “Isolating her? I was basically the human Lyft for half the family,” I said. “My parents visited. My sister visited when she felt like it. Aunt Cheryl was there constantly. If anything, I fought to give Pam quiet time. She was exhausted.”

“That matches the nursing notes,” Lopez said, flipping a page. “They indicate multiple visitors, no concerns about isolation.”

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Sutton’s mouth twitch. He’d seen enough of these to know when the facts were lining up.

At one point, Lopez asked if I’d felt entitled to the inheritance.

“Honestly? No,” I said. “I felt terrified. My parents always told us that money is complicated and you shouldn’t talk about it. Pam was the only one who taught me to talk about it like it was just another tool. Being left in charge felt like being handed a very sharp knife and asked to cook dinner without cutting anyone.”

“Interesting metaphor,” Lopez said.

“Sorry,” I muttered. “Occupational hazard. I work in marketing.”

She smiled again, then turned to Aunt Cheryl. “Ms. Allen, you were present the day the trust was signed?”

“I was,” Aunt Cheryl said. “Pam asked me because she knew Trevor and the others would not like her decision. She wanted someone to witness who wasn’t financially involved.”

“And in your view, was Pamela thinking clearly that day?” Lopez asked.

“She was more clear than some people I’ve met at thirty,” Aunt Cheryl said dryly. “We joked about it. She said, ‘Cheryl, I may be dying, but I can still read a balance sheet.’ Her oncologist came in halfway through and they discussed her treatment plan in detail. She understood exactly what she was doing.”

Lopez made another note. “The complainant also alleged that Pamela ‘always intended’ to leave her estate equally to her children and grandchildren and that this trust was a sudden deviation. Do you have any insight into that?”

“Yes,” Aunt Cheryl said. “It was a deviation—from a plan that depended on people behaving responsibly. When it became clear they wouldn’t, she adapted. That’s not undue influence; that’s common sense.”

“Who is ‘they’?” Lopez asked, though I could tell she knew.

“My nephew Trevor and my niece Sabrina,” Aunt Cheryl said. “I love them. They are not good with money. They treated Pam like a safety net. Pam decided she didn’t want to be a safety net anymore. She wanted to be a rope for someone who would climb.”

Lopez’s gaze flicked between us. “Thank you. That helps.”

At the end of the interview, she clicked off the recorder and gathered her things.

“One last question,” she said, pausing. “Is there anything you haven’t told me that you think I should know?”

I hesitated, then decided that if we were going to rip everything open again, we might as well be thorough.

“At my parents’ house, a few days after the funeral, I saw trust forms on their side table with what was supposed to be my signature on them,” I said. “It wasn’t. They were trying to redirect funds without my consent. I documented it. Mr. Sutton notified the bank. It was one of the reasons we locked things down so tightly.”

Lopez’s eyebrows lifted a fraction. “Do you have those photos?”

“Yes,” I said. “I can email them.”

“Please do,” she said. “Thank you for your time.”

When she was gone, the room felt like someone had opened a window. Sutton exhaled audibly.

“You did very well,” he said. “Calm. Clear.”

“I feel like my insides are vibrating,” I admitted.

“That’s normal,” Aunt Cheryl said briskly. “Come on, let’s go get you something with sugar in it.”

Over donuts and coffee at the strip-mall place down the street, Aunt Cheryl filled me in on the family gossip I hadn’t wanted but probably needed.

“Ray’s the one who filed it,” she said without preamble. “I called your mother this morning. She admitted it. He convinced them this was a ‘simple review’ that might ‘restore fairness.’”

My jaw clenched. “So my parents signed onto this?”

“They let Ray use their hurt to justify his greed,” she said. “Again. Hurt people are very useful to manipulators, honey. It doesn’t excuse it—but it explains why they keep picking up the phone.”

“I thought they were… done.” I stared at the donut I’d been halfway through. My appetite vanished.

“They are more done than they were,” Aunt Cheryl said. “But they are not healed. Big difference. And Ray knows exactly which wounds to poke.”

I drove home that afternoon feeling like the ground under my carefully rebuilt life had shifted a few inches sideways. The foundation was steady; the work made sense. But the family layer—no amount of budgeting could make that line up neatly.

That evening, Sabrina knocked on my door.

I hadn’t told her about the complaint. Apparently someone else had.

She stood in my doorway, shoulders hunched, hair pulled back in a no-nonsense knot. She’d switched from luxury highlights to box dye months ago; it suited her honesty better.

“Can I come in?” she asked.

I stepped aside. “Sure.”

She hovered in the entryway like a stranger. “Ray called me,” she said. “He said there’s another ‘chance’ to fix Grandma’s mistake. I hung up on him. Then I called Mom. She… told me about the complaint.”

I studied her face. “And?”

“And I told her she was out of her mind if she let that man drag our family back into court,” Sabrina said. Her eyes were bright, but not with the old defensive heat. “I told her if she didn’t call the investigator and retract whatever she’d said to support it, I’d stand up in any hearing and tell them exactly what happened at that dinner table. The fake signature. Everything.”

I leaned against the back of the couch. “What did she say?”

“She cried,” Sabrina said. “You know Mom. Then she said she’d ‘already started something’ and didn’t know how to stop.”

“Right,” I muttered. “That’s the story of her life.”

Sabrina stepped closer. “I know you don’t have to believe me, but I am not part of this, V. I was stupid before. I was selfish and entitled and I wanted your money like it was a moral right. But I’m not that person anymore. I don’t want to be.”

I believed her more than I wished I did, which hurt in its own way.

“You remember that night?” I asked. I’d never actually asked her to tell me.

She flinched. “Every frame of it,” she said. “Mom had the papers. Dad said we were just ‘streamlining’ what Grandma would have wanted. Ray had told them it was ‘just paperwork’ and that ‘no one would get hurt.’ Mom asked me to copy your signature because my hand was steadier. We practiced on scrap paper.”

The room tilted for a second. The title of my life—At Family Dinner, I Accidentally Saw My Mother And Sister Using My Fake Signature—suddenly had detail I’d never wanted.

“You practiced,” I repeated.

“Yeah,” she whispered. “I thought it was… I don’t know. A hack. A workaround. I’d been living on hacks for years. I didn’t think about how illegal it was. Or how much it would hurt you. I just thought about the fact that my credit cards were maxed and the repo guy had been circling. I told myself you’d be fine. You always are.”

It was like watching a past version of her stand between us, begging to be understood and condemned at the same time.

“I knew you’d hate me if you found out,” Sabrina continued. “But I told myself you’d get over it. That money would make everything smoother. That we’d just… adjust.”

“And when I confronted you?” I asked.

“I panicked,” she said. “I went for your phone like it was the problem. I called you selfish because it was easier than admitting what I’d become. A thief in designer shoes.”

We stood in silence for a long moment.

“Why are you telling me all this now?” I asked quietly.

“Because Ray is trying to use that night as ammunition against you,” she said. “He told Mom that if she ‘came clean’ about the forgery, they could argue you freaked out and ‘forced’ Grandma to lock everything up. He’s twisting the story. And I can’t stand the thought of him getting to tell any version of that night without me there to correct it.”

Anger flared in my chest, but it wasn’t aimed at her this time. I knew Ray’s type. Manipulators are like marketers with no ethics; they know how to spin hurt into leverage.

“So what do you want to do?” I asked.

“I want to talk to that investigator,” she said. “I want to tell her that Grandma was clear, that you didn’t force anything, and that if anyone exerted pressure in this family, it was the rest of us on you. And I want to tell her that if I ever touch a signature that isn’t mine again, she can personally drag me to jail.”

I huffed out something between a laugh and a sob. “That’s… specific.”

She shrugged, eyes shining. “I’m good with specifics now. They keep me from lying to myself.”

I thought of the foundation, of the teens and the moms and the tired retirees who came to our workshops. We told them change was possible, but we didn’t pretend it was painless. Here was Sabrina, living proof. It would have been easier to believe she was permanently the villain and keep my narrative simple. Life rarely lets you get away with that.

“Okay,” I said finally. “I’ll text Sutton. He can loop you into the process. But Sabrina—”

“Yeah?”

“This doesn’t erase what happened,” I said. “It doesn’t magically restore trust. It just… matters. That you’re willing to stand on the record now.”

“I know,” she said. “Trust is credit. I tanked my score years ago. I get that it takes time to rebuild.”

The fact that she used my own workshop metaphor on me almost made me smile.

In the weeks that followed, Lopez interviewed Sabrina and, eventually, my parents. I wasn’t in the room, but I heard enough afterward. Sabrina told the truth. She didn’t minimize. She didn’t excuse. She described, in painstaking detail, how they’d practiced my signature at the dining table. She explained the difference between what they’d told themselves about Grandma’s wishes and what Grandma had actually said.

My parents, cornered by facts and by their own exhaustion, finally stopped trying to rewrite history. They admitted to Lopez that they’d let Ray stir them up again. They retracted their support for the complaint. They signed a statement saying they believed Pamela had been clear-headed and that they did not, in fact, think I’d coerced her.

It was like watching dominoes fall in slow motion, this time in my favor.

A month later, Lopez called me.

“The elder-abuse review is closed,” she said. “We found no evidence of undue influence or exploitation. The complaint will be dismissed, and the file sealed. If anyone attempts to use elder abuse as a basis to challenge the trust again, this review will be part of the record.”

I leaned against the kitchenette counter at the office, gripping my phone. “So… that’s it?”

“That’s it,” she said. There was a pause. “Off the record—your family is… complicated.”

I laughed, a short, startled sound. “That’s one word for it.”

“Not the worst I’ve seen,” she said. “And for what it’s worth, your grandmother sounds like someone I wish I’d met. She was ahead of most of the families I deal with.”

“She would have had color-coded charts for your caseload,” I said automatically.

“I have a feeling you inherited that part,” Lopez replied. “Have a good day, Ms. Davis.”

When I hung up, I realized my hands were shaking. Jenna appeared at my elbow like she had a sensor for my cortisol levels.

“Well?” she asked.

“They closed it,” I said. “No evidence. Complaint dismissed.”

She didn’t say anything. She just pulled me into a hug that felt like an exhale.

“It’s over,” she murmured into my hair.

“For now,” I said. “With my family, ‘over’ is always a tentative word.”

“Then maybe it’s time you define what ‘over’ means,” she said. “On your terms.”

The idea lodged in my chest like a seed. For years, I’d been reacting—to their crises, their lawsuits, their apologies, their new crises. Maybe it was time to initiate something instead. Not another legal maneuver. Something… human.

Pamela had always said that budgets were plans, not punishments. Maybe boundaries could be that too.

Part Five

The idea came to me in the least dramatic place possible: the produce aisle at Trader Joe’s, staring at a display of lemons.

They were stacked in a neat pyramid, bright and yellow and ridiculous, and for some reason they made me think of Grandma Pam’s old Imperial Beach kitchen, where she’d kept a chipped lemon-shaped sugar bowl on the counter and used it to hold her grocery receipts. “You can tell who people are by what they keep,” she’d say, flicking the lid open with one finger.

I realized, standing there among the bagged kale and organic apples, that my family was still keeping the wrong things. We were keeping grudges and guilt and half-finished apologies. We were hoarding regret like it earned interest. What we weren’t keeping was any shared ritual that wasn’t soaked in drama.

Family dinner had become, in my mind, a crime scene. But it had once been a place where we laughed over overcooked pasta and watched sitcom reruns in the background. If the original trauma of this story was “At family dinner, I accidentally saw my mother and sister using my fake signature,” maybe the ending needed another dinner—one where every signature was real, and every agreement was above the table.

So I did something that surprised even me.

I invited them all over.

“I’m hosting dinner,” I texted in a group chat I hadn’t used in years. “Me, Aunt Cheryl, Jenna, you two, Sabrina. No Ray. Nonnegotiable. Sunday, six p.m. My place. We’re going to talk like adults. If you can’t handle that, say so now.”

There was a long silence. I almost convinced myself they’d ignore it. Then the dots appeared, disappeared, reappeared.

Sabrina: I’ll be there.

Mom: We would love to. Thank you, sweetheart.

Dad: We’ll be respectful. Promise.

I stared at that last one for a while. Respectful. It was a low bar and a mountain at the same time.

On Sunday afternoon, Jenna helped me turn my small condo into neutral territory. We moved paperwork off the dining table, lit a couple of unscented candles, and put on a playlist that had nothing to do with anyone’s nostalgia. I cooked Pamela’s lasagna recipe, because it felt right, and Jenna made a salad so fancy it could have been a centerpiece.

“You’re sure about this?” she asked as she arranged the forks.

“No,” I said. “But clarity rarely comes from staying home alone.”

She nodded. “If anyone starts brandishing legal threats, I’m throwing feta at them.”

At six on the dot, there was a knock. Sabrina stood outside in jeans and a sweater, holding a store-bought pie like a peace offering. Behind her, my parents hovered—Dad in a collared shirt that had seen better ironing, Mom with her hair done but her eyes softer than I remembered.

“Hi,” I said.

“Hi,” Sabrina echoed.

“Hi, pumpkin,” Mom whispered.

We all shuffled inside like guests in someone else’s life. Aunt Cheryl arrived moments later, breezing in with a bottle of sparkling apple cider and a look that said she was ready to referee if needed. Jenna poured drinks. We made small talk about traffic and the heat wave. It felt almost absurd.

We sat down to eat. For a while, the clink of forks and low hum of conversation did the heavy lifting. Then Dad set his fork down and cleared his throat.

“Before we say anything else,” he said, “your mother and I owe you an apology. Another one, maybe, but… an important one.”

Mom nodded, eyes already swimming. “We let Ray get into our heads,” she said. “We let our hurt speak louder than our love for you. Again. We didn’t file that complaint ourselves, but we let him use our names to give it weight. It was wrong. We know it was wrong.”

“We keep saying we were trying to help the family,” Dad added, voice thick. “But the truth is, we were trying to avoid facing the mess we made. You were right to protect what Grandma left you. You were right to protect yourself. You shouldn’t have had to protect yourself from us.”

They sat there, older than I remembered, hands folded, waiting for a verdict.

I took a breath. “I appreciate you saying that,” I said. “But apologies only go so far if nothing changes. So here’s what I need if we’re going to have any kind of relationship.”

The marketing specialist in me had prepared a list. I pulled out a thin folder from under my chair and set it on the table. Inside were three sets of documents, each neatly clipped.

“For years, money has been the weapon in this family,” I said. “We’ve used it to manipulate, to guilt, to excuse. I don’t want that anymore. But I also don’t want to pretend Pamela’s trust doesn’t exist. It does. It changed all our lives. So I talked to Mr. Sutton. I talked to a financial planner. I talked to Aunt Cheryl. And I came up with a plan that honors Grandma and doesn’t make me your ATM.”

I slid one stack toward my parents, one toward Sabrina, and kept one for myself.

“These are agreements,” I said. “Not punishments. Not bribes. Agreements.”

Mom’s hand trembled as she picked up the top page. “What kind of agreements?” she asked, wary.

“For you two,” I said, “I’m setting up a modest retirement account funded from the trust. Not enough to erase every consequence, but enough that you’re not living one medical bill away from disaster. It vests gradually over the next ten years. There are conditions—standard things, like not using it as collateral for risky loans. You can’t cash it out early without penalties. It’s there for stability, not for another round of bailing out bad decisions.”

Dad blinked rapidly, scanning the document. “We… we’d be grateful,” he said. “You don’t have to do this.”

“I know,” I said. “But I want to. On my terms.”

Sabrina flipped through her stack. “And this?” she asked.

“For you,” I said, “I’m setting up a small education and emergency fund. You’ve been working your ass off at the bakery and volunteering with the foundation. If you decide to go back to school for financial counseling courses or anything that helps you build a stable career, this can help with tuition. If your car dies and you need it to get to work, there’s a process for requests. It’s not a blank check. It’s a tool you can choose to use responsibly.”

She swallowed. “There’s a line here about working fifteen hours a week minimum,” she said, half-laughing, half-crying.

“Yeah,” I said. “Grandma would haunt us all if I funded laziness.”

The table rippled with a nervous chuckle.

“And there’s one more piece,” I added. “These agreements say we won’t sue each other over Pamela’s trust again. No more challenges. No more complaints. No more ‘simple reviews.’ We put it in writing that her wishes stand. Forever. If you sign, you’re saying you accept reality and you’re done letting people like Ray poke at old wounds.”

Mom’s fingers tightened around the pen Sutton had given me earlier. “I’ll sign,” she said immediately. “Please. I’m so tired of fighting ghosts.”

Dad nodded. “Me too.”

Sabrina looked at me. “And you?” she asked quietly. “What do you get out of this, besides a smaller balance sheet?”

I considered the question. Then I answered honestly.

“I get to stop wondering when the next shoe will drop,” I said. “I get to know that if I invite you to dinner, we’re not secretly fighting over documents behind the scenes. I get to put Grandma’s money to work the way she wanted: to build security, not drama. And… I get to let go of some of the anger, because I’ll know I chose something other than revenge.”

The room went very still.

“Okay,” Sabrina said. “Then I want that too.”

We didn’t rush. We read. We asked questions. Dad worried about tax implications; Sutton had already factored those in. Mom fretted about whether accepting this meant accepting that she’d been wrong all along; Aunt Cheryl gently pointed out that growth usually does. Sabrina asked if there was a clause for what happened if she relapsed into old habits; I told her there was—accountability provisions, not gotchas.

Finally, one by one, they picked up the pens.

For a moment, as I watched my mother write her name, a flash of that old night surged up—the practiced curve of my stolen signature, the cheap ballpoint gliding over paper. This felt like an exorcism of that image. The signatures now were slow, shaky, utterly authentic.

They signed, and then I did. Not forged by anyone’s hand but my own. Not under duress, not in secret, not half-understood. My name, the way I’d been writing it in ledgers since I was twelve. The way Pamela had once admired, saying, “Look at that. You sign like someone who expects to be taken seriously.”

When it was done, Jenna gathered the signed documents and slipped them into a manila envelope.

“I’ll drop these with Sutton first thing tomorrow,” she said. “Consider them backed up six ways from Sunday.”

I exhaled, a long, shaky breath that felt like it had been waiting in my lungs for years.

“Now,” I said, “can we please eat dessert like a normal family that just signed legally binding contracts at the dinner table?”

Sabrina snorted. “Nothing says ‘normal’ like dessert after notarized agreements.”

“We live in Irvine,” Jenna said. “This is basically culture.”

We laughed, and this time it wasn’t the brittle, defensive laughter of people pretending nothing was wrong. It was the tentative kind that comes when something has actually shifted.

Over pie and coffee, the conversation drifted to gentler topics. Dad told a story about his first job mowing lawns, how he’d once underbid so badly that he’d made negative money. Mom admitted she’d started attending one of the budgeting workshops at her church. Sabrina talked about a certification program she’d been eyeing in credit counseling. Aunt Cheryl toasted Pamela with sparkling cider, citing her as “the original spreadsheet queen.”

At some point, Mom reached for my hand.

“I know we may never get back to what we were,” she said softly. “Maybe we shouldn’t. But I hope someday, when you think of family dinner, you won’t only remember the night we tried to steal from you.”

I looked around the table—at the lasagna pan scraped nearly clean, at the stack of signed papers resting by the napkin holder, at Jenna’s reassuring presence, at Aunt Cheryl’s proud smile, at Sabrina’s hopeful eyes, at my parents’ worn faces.

“I don’t,” I said. “Not anymore.”

Later, after everyone had gone and the dishwasher hummed in the background, I sat at my desk with Pamela’s old ledger open in front of me. The pages were more fragile now, the ink faded. I flipped to a blank page in the back and drew the familiar columns: Date, Income, Expenses, Savings, Notes.

In the notes section, I wrote:

“Family dinner. Signed agreements. No forgeries. Net gain: peace.”

I stared at the words for a long moment, then added another line, the kind of moral I used to resist but now felt ready to claim.

“Lesson: You can’t control what people do with your name, but you can decide what you sign it to.”

I closed the ledger and set it back in its drawer.

Outside, Irvine’s streetlights painted tidy pools of gold on the pavement. Somewhere, in a rental house smaller than the one I’d grown up in, my parents were probably going over their copies of the agreement, realizing that for the first time in years, a financial plan in their lives didn’t involve quietly asking me to fix something. Somewhere else, Sabrina was probably circling college program websites, calculating tuition against hours she could work.

And in the spaces where resentment used to sit like heavy furniture, there was something unexpected: room.

Room for new stories about us. Room for the foundation to keep growing. Room for Pamela’s lessons to reach people who would never know her name but would feel her legacy every time they set a boundary and said, “No, I won’t sign that,” or, “Yes, I’ll help you—but this time with a plan.”

My name sat on those documents in ink that had barely dried. Not an ambush, not a theft, not a forged line on a page in someone else’s living room. My signature, this time, was a choice—an active, imperfect, hopeful choice.

That, more than any court ruling or bank balance, felt like the real inheritance.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Sister Hired Private Investigators to Prove I Was Lying And Accidentally Exposed Her Own Fraud…

My Sister Hired Private Investigators to Prove I Was Lying And Accidentally Exposed Her Own Fraud… My sister hired private…

AT MY SISTER’S CELEBRATIONPARTY, MY OWN BROTHER-IN-LAW POINTED AT ME AND SPAT: “TRASH. GO SERVE!

At My Sister’s Celebration Party, My Own Brother-in-Law Pointed At Me And Spat: “Trash. Go Serve!” My Parents Just Watched….

Brother Crashed My Car And Left Me Injured—Parents Begged Me To Lie. The EMT Had Other Plans…

Brother Crashed My Car And Left Me Injured—Parents Begged Me To Lie. The EMT Had Other Plans… Part 1…

My Sister Slapped My Daughter In Front Of Everyone For Being “Too Messy” My Parents Laughed…

My Sister Slapped My Daughter In Front Of Everyone For Being “Too Messy” My Parents Laughed… Part 1 My…

My Whole Family Skipped My Wedding — And Pretended They “Never Got The Invite.”

My Whole Family Skipped My Wedding — And Pretended They “Never Got The Invite.” Part 1 I stopped telling…

My Dad Threw me Out Over a Secret, 15 years later, They Came to My Door and…

My Dad Threw Me Out Over a Secret, 15 Years Later, They Came to My Door and… Part 1:…

End of content

No more pages to load