At 2 A.M. on Patrol, I Found Grandma Abandoned at a Gas Station. What Happened Next Shocked Everyone

Part One

The red and blue wash from my cruiser flickered across the empty highway and splashed the glass of the all-night station like a heartbeat. The place was a Speedy Mart at the I-75 exit where the asphalt thins to two lanes and the pines lean in. I had no reason to stop except for the promise of bad coffee and five minutes of warmth before finishing my route along Clayton County’s sleeping neighborhoods. It was the kind of fall shift that usually delivered noise complaints, maybe a DUI, maybe a possum pretending to be dead in the lane. Never anything that stuck.

Until it did.

She sat on the metal bench under the buzzing beer sign, hunched in a faded cardigan, her white hair twisted up like she’d tried to make herself neat for a place that had never dressed for anyone. A single grocery bag rested by her ankles. When her thin fingers fumbled the zipper of her coat, something in me pulled taut. I slowed. I took three more steps. And the whole night turned.

“Grandma?” I said. It came out a whisper because names spoken at the wrong volume in the wrong place can spook the truth.

Her face lifted. Those pale blue eyes—my eyes—widened with confusion and then collapsed with relief. “Ellie?” My full name is Ellanar, but no one who loves me calls me that.

Fifteen years unspooled between us in one breath. In the time it took to cross the space from curb to bench, I remembered her kitchen: the sound of the kettle burbling, hymns under her breath, the way she’d wipe crumbs toward her palm with one sweep like a magician clearing the table of everything hard. I remembered her standing between me and my father’s rage, an eighty-pound shield with a spine made of prayer and mule. None of that armor was with her now. She was eighty-eight and alone at two in the morning in front of a gas station.

I knelt, the radio at my shoulder muttering about a noise disturbance on Tara Boulevard. My badge felt heavier than the gun at my hip. “What are you doing here? Who brought you?”

She tried to straighten. “They did.”

“They?”

“Your mama and daddy. Said they’d be right back. It’s been… well.” She glanced toward the road as if the asphalt might be kind enough to deliver headlights shaped like regret.

The soda machine hummed. The neon beer sign buzzed. Somewhere behind the counter, the clerk coughed. Everything else in the world stopped.

Fifteen years earlier, my father, David Whitaker, had kicked me out of the house three days before my high school graduation. I had a duffel bag, a friend with a couch she wasn’t allowed to offer, and a refusal to apologize for wanting to attend the police academy. He called me useless as if nothing in me could be recycled, as if he were discarding plastic. I survived anyway. I learned to pour coffee at Waffle House without flinching at sweethearts tossed like coins. I learned to run mile after mile under Georgia sun and the kind of officers who yell not because they hate you but because the world sometimes will. I learned to hang a uniform on my body and call it mine.

And now, on a patrol that should have been forgettable, I had stumbled across the proof that the man who had thrown me away had learned nothing about what is and is not disposable.

I took her hand—cold, bird-light—and stood. “You’re safe,” I told her. “You’re coming with me.”

“What about your father?” Her voice was a papercut.

“My father made his choice a long time ago,” I said. The words came out steelier than I meant, but I didn’t pull them back. “Tonight I make mine.”

I buckled her into the front seat like she was the most important passenger I had ever transported. On the drive across Jonesboro toward my little brick place on Oak Street, I kept checking the rearview the way you do when you’re sure the past knows the route to your house. She held the grocery bag in her lap like a passport. A Bible stuck out from the top, edges worn ragged with years of loving and being loved by it.

My place smelled like lemon cleaner and sleep. I settled her on the couch, tucked a worn quilt around her legs, put water on to boil, and brewed tea the way she used to pretend wasn’t too sweet while finishing every drop. Her hands stopped shaking sometime between the first and second sip. She exhaled like someone who had been holding her breath outside for hours.

“You always were stronger than he said,” she murmured.

I sat at the edge of the coffee table and covered her hand with mine. “Rest. Tomorrow we start something he’ll never see coming.”

It’s a thing people say in movies when revenge is the business at hand. But for me, the plan was never fists or racing engines. I’d sworn an oath to a different kind of power. Sometimes justice is a flashlight pointed where a man hopes no one looks. Sometimes it’s paperwork with teeth.

By sunrise the kitchen smelled like oatmeal and the good coffee I pretend to hate. Grandma Ruth woke up slow, blinking against the rectangle of light sliding across the old rug my great-aunt had woven decades ago in Griffin. “Is it really morning?” she asked, like time might have lied to her, too.

“It is. And you’re home.”

I set her pill organizer on the table and saw that two evening slots from the previous days were still full. The morning squares had been punched out—just enough compliance to quiet a conscience. My jaw tightened.

“I think your father threw out my address book,” she said suddenly. “Been looking for it all week. Maybe I just misplaced it.”

Maybe. Or maybe the book with my number in it was the one thing he couldn’t afford for her to find.

I pulled a spiral notebook from the drawer and set it on my knee. Habit. Memory lies; ink doesn’t. “What time did they bring you to the station?”

“Just after eight. Your mama went in for a drink. Your daddy opened the trunk.” She paused, frowned, as if there were a word on the edge of her tongue and the room kept moving it. “He told me to sit and rest. I did. Then they… well. They pulled away. I thought they were circling back. I waited until the lottery sign clicked off.” She said it like a liturgy she’d practiced while counting minutes in the cold.

I wrote it down. 8:00 p.m. drop. Waited until closing. Found at 2:00 a.m.

I called in a family emergency to dispatch and turned the radio down. Then I called Tessa—my best friend since the kind of childhood where we ate gas-station popsicles on the curb and shared a single pair of skates—now a nurse at Southern Regional. She promised to squeeze Grandma in that afternoon. I texted Marcos Alvarez in Investigations—a detective with good instincts and better timing—and asked him to meet me later. Finally, I made one more call, the kind that rearranges the furniture of a life: an elder-law attorney named Carol Jenkins who had once made a nursing home back down so hard they practically put ramps on their pride.

Grandma finished her tea. “Don’t make too much of it,” she said, reflecting on a lifetime of minimizing harm to make rooms livable. “I don’t want trouble.”

“Trouble already happened,” I said. “Now we’re giving it a name.”

I dressed Grandma for the doctor’s visit—her best blue sweater, fresh socks, the small gold brooch she insisted made her feel like a lady—and drove to Southern Regional. The intake nurse’s fingers were gentle; the blood pressure cuff was not. Dehydration. Blood sugar in the high wrong. Mild malnutrition. Nothing a few weeks with regular meals and someone who notices could not fix. That was the point. This was not a tragic decline you write poems about. This was neglect with a calendar.

After I settled her back under the quilt with daytime TV murmuring about people who shouldn’t have married in the first place, I drove back to the Speedy Mart. The clerk, a lanky twenty-something with kind eyes named Darnell, glanced up from stocking chips and laughed. “Back so soon, officer?”

“Ellie,” I corrected. “Can I take a look at your exterior cams from last night? Eight to midnight.”

He pointed his chin toward the office. “Boss keeps it on a hard drive. You’ll need a warrant, technically.”

“Technically,” I said. He ignored the word the way men who hate paperwork do. Ten minutes later, I was watching a grainy parade of facts. 7:58 p.m. The white Crown Vic eased up to pump two. I knew the dent in the rear bumper; my brother Caleb had put it there backing into a mailbox in 2005. Mom went inside. My father opened the trunk. Grandma stepped out slowly—hand on the door frame, small bag clutched like a parachute—and shuffled to the bench. Dad shut the trunk. The car idled. Then it pulled away.

No return. No circling. No headlights softening back across the tarmac. If they had meant to come back, the camera would have said so. Cameras don’t respect excuses.

“Can I get a copy?” I asked.

Darnell slid a thumb drive across the desk. “For you? Yeah. Just don’t make me famous.”

“You’re not the star of this film,” I said.

I drove back along I-75 with the kind of stillness that only happens when your anger has plans. At the house, I pulled up property records, opened my laptop in the patch of sun drifting across the table, and dug through deeds the county should have archived better and didn’t. “Ruth Eleanor James Whitaker,” I read out loud when I found it—her name in faded typewriter ink from 1972: co-owner with right of survivorship. When Grandpa Henry died, that paper had quietly shifted the house on Willowbend onto her shoulders. My father had never filed the paperwork to take it off. The arrogance of men who believe possession is ten-tenths of the law is a snake that eventually remembers to bite.

“Grandma,” I said that night, setting the folder on the quilt beside her. “This is still yours.”

Her eyes filled and then did not spill. “So I could have gone home all this time?”

“Yes. But not with him there.” I paused. “Now you can decide what happens next.”

She reached for my hand. “What do you think I should do?”

“I think you should do what you want,” I said. “And this time I think you should do it without apologizing.”

The next morning we went to the courthouse. The marble floor amplified every step and made me too aware of my boots. I filed a petition for emergency guardianship. Carol Jenkins met us there in a navy blazer that meant business and mercy in equal parts. We slid the footage, the doctor’s notes, and my incident report across a counter that had seen a thousand messy families and was ready for one more. Carol’s pen made small staccato sounds on the line where my grandmother signed. Her hand trembled; the signature did not.

I wish I could tell you I did not want to pound on my parents’ door and ask, in a voice big enough for every neighbor to hear, if this was what Jesus meant when he said honor thy father and mother. But a badge gives you a clock and a leash. Sometimes the smart way through is slower and sharper. So I did the work. I called the county records office. Mr. Dalton with the half-moon glasses found the deed and tapped the line under Grandma’s name with the kind of satisfaction bureaucrats get when the universe of paperwork reveals its secret mercy. I made a second copy. I put it in a sandwich bag. We do what we must.

I took Grandma for a drive down Willowbend the day before the hearing. The oak tree she’d planted when my mother was small threw shade across the porch she had painted three times—twice Henry, once her. My mother watered geraniums in silence while my father sat in a lawn chair and let the day sweat. They looked ordinary. The ordinary is far more dangerous than the monstrous because you invite it to lunch.

“That was my home longer than it’s been his,” Grandma said, voice small as the space between truth and permission.

“It still is,” I said. “You just forgot you were allowed to say so.”

That night, the house felt like a chest before a held breath. Grandma fell asleep with her Bible open to Psalms. I sat on the porch with the mug I didn’t need and watched crickets vibrate the dark. I imagined the judge’s face set into the familiar lines of men who have seen too much and decided to be stern anyway. I imagined my father’s jaw when the paper slid across wood. I imagined a gavel and the weight a single sound can carry.

When the morning came, we were ready.

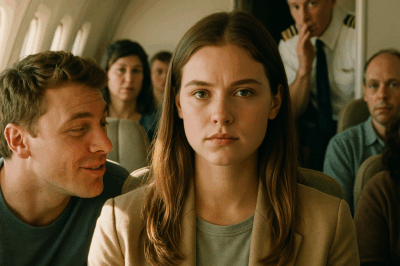

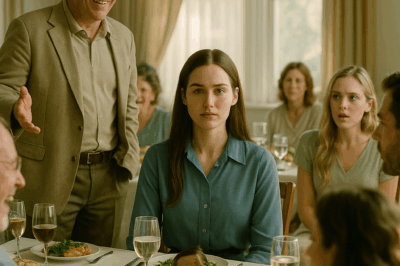

The courtroom smelled like lemon oil and last week’s argument. Neighbors filled the benches because stories travel faster than subpoenas. My parents sat at the respondent’s table. Dad’s jaw clenched like it thought it was tough enough to crack granite; Mom twisted her wedding ring like she might screw it into a different shape if she only tried harder.

“En re Ruth Whitaker,” the clerk intoned. “Petition for guardianship and recognition of property rights.”

Carol stood. “Your Honor, we represent Ruth Whitaker. We submit evidence of abandonment and neglect by her son and daughter-in-law, David and Linda Whitaker. We request transfer of guardianship to her granddaughter, Officer Ellanar Whitaker. We also request this court acknowledge Ruth Whitaker as the sole legal owner of 214 Willowbend Drive.”

We played the tape. A grainy white car. A trunk. A small figure on a bench. Tail lights shrinking to red pinpricks in the dark. The courtroom inhaled as one. The judge leaned forward.

“Mr. Whitaker,” he said. “Is that your vehicle?”

“Yes.”

“And that is your mother?”

“Yes.”

“You left her there.”

“We—we were coming back,” Dad said. The lie had bad grammar.

The doctor’s report came next. Dehydration. Malnutrition. Missed medication. Carol’s voice did not tremble. My mother’s did not speak.

“Officer Whitaker,” Carol said, “please describe how you found your grandmother.”

I stood. Uniform creased. Badge catching cheap fluorescent. “On patrol,” I said, “I pulled into the Speedy Mart around 0200 hours. I observed my grandmother seated on the exterior bench, alone, with a single bag of belongings. She stated my parents had left her there hours earlier. I transported her to my residence, secured medical evaluation, and obtained surveillance corroborating her account.”

“Why are you petitioning for guardianship?”

“Because she deserves safety,” I said. “Because she deserves dignity.”

When the judge ruled, he did not perform. He did what good men do when the facts leave little room for anything but backbone. “Guardianship is hereby granted to Officer Whitaker,” he said. “This court recognizes Ruth Whitaker as sole legal owner of the residence on Willowbend Drive.” The gavel made the sound lumber must make when it forgives the tree.

My father stood so fast his chair scraped. “You can’t do this,” he shouted—at the judge, at me, at the paper that refused to admit it belonged more to ink than to ego.

“It was never yours,” the judge said. “Not on paper. Not in practice. Not anymore.”

Outside, microphones waited like birds with long beaks. “Officer Whitaker,” a reporter asked, “how does it feel to win?”

“It isn’t winning,” I said, Grandma’s hand steadying my elbow. “It’s a woman getting back what should have been hers all along. It’s dignity with a case number.”

That night, we sat on the porch and let September move through the trees. Grandma rested her head on my shoulder. The porch light made a tiny universe of moths. “Your father lost today,” she murmured, “but you didn’t win hatred.”

“No,” I said. “I won quiet.”

And for the first time in fifteen years, I slept like thunder had moved to a different county.

Part Two

The week between the guardianship ruling and the criminal hearing stretched and snapped like a rubber band. The house on Oak Street learned new rhythms—Grandma humming as she watered the violets on the sill; me cooking more than eggs; both of us learning how to be full without apologizing for it. Paperwork still colonized my table. So did casseroles; people who used to nod to us at Kroger now pressed food into our hands and said the word brave like it had always been my middle name.

We drove by the old house one afternoon as the sun folded itself into the treeline. “Feels strange,” Grandma said, studying the cracked driveway and the porch she’d scrubbed on knees that no longer cared to kneel. “To look at it like it belongs to me again.”

“It always did,” I said. “He just got good at convincing you otherwise.”

Attorney Carol Jenkins pushed the property papers through faster than I could have on my own. Mr. Dalton at the records office stamped copies with bureaucratic delight. I learned where in a folder to place a piece of paper so it cannot be betrayed by an accidental slip. By Friday noon, we were in Carol’s office with pens that would not run dry. “Ruth,” she said gently, “you can keep it, rent it, sell it. It’s yours. Your granddaughter has POA to move quickly if that’s best for your care.”

Grandma took the pen. “I want it sold,” she said. “I want to use the money to live instead of apologizing for drawing breath.”

She signed. I countersigned. The floor of my life shifted half an inch toward level.

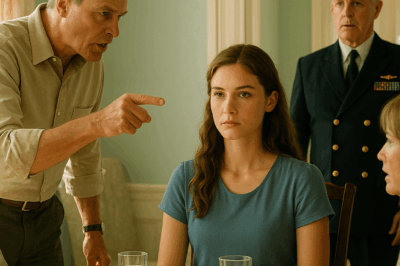

Dad heard the news by dinner. He arrived at my porch with fists and beer breath and the old storm rolling in his eyes. He pounded the screen door until the spring whined. “You think you can take what’s mine?”

“It was never yours,” I said, stepping onto the top stair so we were eye to eye, the porch light drawing hard edges around both of us. “You left her at a gas station. You made a decision. This is the consequence.”

“You always hated me,” he said. “Since the day you were born. Came out looking for a fight.”

“I came out looking for air,” I said. “You refused to learn the difference.”

He leaned in. I didn’t back up. When you’ve been raised on thunder, you learn to interpret distance like weather. Behind me the living room lamp made a warm oval around Grandma’s chair. My sidearm sat heavy at my hip, locked and holstered by habit and law. I didn’t touch it. I didn’t need to. Sometimes the most powerful thing in a room is the fact that you could act and you choose not to.

“You’ll regret this,” he hissed.

“I already do,” I said. “I regret that it took fifteen years.”

He left with words that sounded like nails thrown in the driveway. We slept anyway.

The sale closed so quietly the windows in Willowbend didn’t rattle. A young couple from Morrow bought the place and set a swing under the oak. They painted the shutters a green that would have made Mom smile if she’d allowed herself the muscle memory. The money sat in an account under Grandma’s name where it would pay for doctors’ visits and fresh fruit and the kind of winter coat she never would have asked for. The county tax office mailed a tidy envelope stamped Paid in Full. Grandma smoothed the paper on her lap and breathed out a life’s worth of held breath. “Well,” she said. “That’s that.”

“No,” I said, smiling. “That’s this. That was then.”

If the guardianship hearing had been a reckoning, the criminal trial was the accounting. The courthouse benches filled again—not just with neighbors but with strangers who had heard the rumor that a county was deciding what love owes. My mother wore her church dress and the expression she saves for funerals. My father wore a dark suit that made him look smaller. Their lawyer looked like a man who had underestimated his own stomach.

The state called it what it was: elder abandonment and neglect, as cold and clean as those words can be when they are not softened by anyone’s need to keep the family picture frame looking nice. The prosecutor, James Holloway, walked the judge through the footage, the medical record, the timeline. He said the word duty enough times that it began to ring in the wood. Dad’s lawyer objected at the edges and got his objections overruled so consistently it became a rhythm.

Grandma took the stand. She swore in under the gaze of a man in a robe and told the truth the way women raised in small churches know how: without decoration. “David is my son,” she said, looking at her hands and then up at the judge. “But he stopped caring for me the minute he left me on that bench. Ellie is my granddaughter. She came. That’s the sum of it.”

The judge listened. You could see him file each sentence in the cabinet behind his eyes. The gavel dropped when he spoke. Guilty on both counts. Community service, fines, mandatory counseling, and—more importantly to the future—permanent revocation of any right to act as caregiver. Consequence had finally beaten volume.

Outside, cameras waited again. I did not say much. “Abandonment isn’t just cruel,” I told the microphones and anybody who would ever be tempted to leave a mother in the cold because she has become inconvenient. “It’s criminal. Today the court reminded all of us.”

We went home. Neighbors we barely knew stopped by with pies and handshakes and tears that made me want to both hug and hide. Mr. Johnson from down the block said, “Folks talk like family is blood. You reminded us it’s protection.” Grandma squeezed his arm the way she squeezes mine when she is thanking me for something I do not know I did.

When the casserole dishes were washed and returning, the house resumed its new sound: a slow, steady bass line of safety.

The story could have ended there, tied off with a judge’s sentence and a yard sale on Willowbend where my father let go of things the way men like him do—one expletive at a time. But life is stitched in smaller threads than courtrooms, and the next chapter lived in them.

Church invited Grandma to Wednesday supper to talk about what we were all pretending was a “situation,” as if a sentence can hold the weight of a winter. She stood at the front with her cane, Dove brooch pinned properly, blue dress ironed within an inch of its hem. “I was left,” she said, voice thin and steady. “I was found. In between, the Lord and my granddaughter held me up. Silence is not love. Protection is. Thank you for your casseroles, but more than that, thank you for listening.”

People clapped the way you clap when you’ve been taught not to but you can’t help it. I sat in the back, the words silence is not love writing themselves into my bones with a pen that would not run dry.

A month passed. Grandma’s color returned from the edges inward. She gained the kind of weight stereotypes have taught women to hate and doctors cheer for. She watered her violets and scolded me for letting laundry sit unfolded and asked after the rookies in my precinct with a curiosity that made them blush when they ran into her in town. Sometimes she would look up from the porch swing and say, “You finally came home.” I would answer, “So did you,” and we would sit there feeling the truth settle around us like the evening.

I saw my mother once at Kroger near the produce, standing too long by the bananas like she could make them ripen with concentration. She looked up. I looked back. For a heartbeat the air thinned. She opened her mouth. She closed it. “How is she?” she asked finally.

“Safe,” I said. There was nothing else to add without building a bridge I did not trust her to step onto.

At work, the rookies asked whether it had felt strange to take your own family to court. “It felt like doing my job,” I said. “Badge or not.” When we rolled up on domestic calls, I saw the women standing at the edge of the yard and the men using volume as if it were virtue, and I carried the memory of a gas station bench like a compass. You cannot save everyone. Sometimes you can save someone.

The last tie to cut came in the mail: the county tax office letter confirming proceeds deposited and liens cleared; the thin line that separated then from now put in writing on paper that would sit in a file who knows where until the courthouse has a flood and loses ten years of records. I framed a copy in the hallway because sometimes you need to pass proof on your way to the bathroom.

We drove out to Willowbend one more time. The new owners had painted the shutters a different green and hung wind chimes. A kid’s bike lay in the yard like a promise. The oak threw its shade exactly the same; trees do not pick sides. Grandma watched the leaves move. “Funny,” she said. “For years that house was a prison. Now, without it, I can breathe.”

“You didn’t lose a house,” I said. “You lost his rules.”

She nodded, eyelids fluttering in the way they do when something painful and good happens at the same time.

Two months later, the station assigned me a midnight shift that felt more like a confession than a rotation. I took the route I took that first night on autopilot and not at all. The Speedy Mart’s neon still buzzed. The beer sign still promised cheap and cold. I pulled in. The clerk—Darnell again—raised a hand like a benediction. “How’s your grandma?” he asked.

“Watching terrible television and critiquing everyone’s shoes,” I said. “Which is to say: perfect.”

“You did right,” he said. “Not everyone does.” It sounded like a benediction and a rebuke for a world too often bored by other people’s pain.

On my way back to the cruiser I sat for a minute on the same bench where she had waited. The metal was colder than I remembered. I imagined her there again—knees together, bag in lap, singing under her breath the hymn that used to steady me when thunder made our windows rattle. Blessed assurance. The tune that had pulled me out of nightmares as a child pulled me forward now, breathing into the place where anger finally loosens its grip and leaves room for gratitude without giving away ground.

I drove home. I opened the front door. Her voice drifted down the hall—humming, then speaking to the violets as if they were listening. Maybe they were. I put my keys in the dish, hung my duty belt on the peg, and felt the click a life makes when it slides into the groove it was made for.

“Ellie?” she called.

“Yeah, Grandma?”

“Is it morning yet?”

“Almost,” I said, smiling because sometimes the truth is better for being slightly wrong. “Almost.”

We sat at the table and watched the sky change shapes behind the oak. Coffee steamed. A bird started up somewhere just far enough away to be music. “I prayed you’d come home,” she said, folding a napkin for no reason but habit. “Didn’t know it would be like this.”

“Me either,” I admitted.

“You didn’t carry hate,” she said. “You carried me.”

I reached across the table and squeezed her hand—veins like blue rivers under paper skin, pulse steady as a metronome. “We carried each other.”

She nodded and looked out at the oak. “Justice is never too late,” she said, like a benediction over the dishes, the day, the whole year.

If you ask me what shocked everyone, it wasn’t the footage or the judge or even the sale. It was what came after—all the quiet a county learned when the loudest man in the room lost his microphone and the truth kept talking anyway. People like to think justice is a gavel or a headline. Sometimes it’s this: an old woman sleeping without fear and a granddaughter who finally kept the promise she made at eighteen with a duffel bag in her hand—to make a life where the people she loves are safe.

There’s a lesson there I offer to anyone who needs it more than I do right now: don’t mistake blood for love, a roof for a home, or silence for peace. And if you ever find yourself under the humming light of a gas station at 2 a.m. with impossible choices creeping up like fog, remember the things that will not betray you—your own name spoken steady, the law when you wield it right, and the hands that taught you how to hold on and when to let go.

We didn’t win. We didn’t lose. We made it right. And some nights, when the crickets sing and the porch smells like honeysuckle, that feels like victory enough.

END!

News

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives. CH2

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives …

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” CH2

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” Part One My name…

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… CH2

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… Part…

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… CH2

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… Part One My…

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. CH2

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. Part One My…

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load