At 1 A.M., My Mom Collapsed at My Door — Dad Hit Her for His Mistress. I Put On My Uniform…

Part One

It was one in the morning when the pounding started—hard enough to shake the deadbolt, frantic enough to wake every dog on the block. I’d barely kicked off my boots after a twelve-hour shift when I heard my name, thin and breaking in the winter dark.

“Sarah—Sarah, open up!”

I yanked the door wide. My mother, Linda Carter of Wharton, Texas, fell into my arms: sixty-two years old, in her nightgown, barefoot, trembling so hard I felt it in my teeth. Her right eye had exploded into purple, her bottom lip was split, and a raw bruise crawled along her jaw where someone’s knuckles had found bone.

She shook against me, clutching at my T-shirt like a drowning woman. “Your father,” she rasped. “He—he hit me. For her. She told him to.”

For a second the hallway swam out of focus. My father. Robert Carter. Retired Army mechanic. The man who taught me to shoot tin cans behind the barn and change a tire on a July roadside. The man whose voice could fill a room and empty a heart. I wanted to believe she’d tripped on the porch, caught her face on the banister, anything but this. But the truth was purple and hot and staring at me.

I carried her inside and laid her gently on the couch, tucking a blanket around her shoulders. She flinched when my fingers brushed her wrists. Faint red rings were forming there, the ghost of someone’s grip.

“Don’t call the sheriff,” she whispered, half-sobbing. “Please. People can’t know. He’ll ruin me. He’ll ruin you.”

“Mom,” I said, voice steadying with every breath, “this isn’t about gossip. This is about the law.” I left her only long enough to walk down the short hall into my room. The closet light hit navy blue: shirt pressed, creases like rules; badge in its leather clip, catching the dim; belt and holster, weighty as a vow. I pulled on the uniform piece by piece. Every buckle made the night sharper. I slid the last round into the chamber. The sound echoed like a door locking behind me.

On my way back, I called the only person I trusted to stand inside the blast radius of a small-town secret: James Ellison, our family lawyer. He answered groggy and then awake all at once when I said, “James. Start the plan.”

A beat. “Are you sure?”

“Yes,” I said. “Start now.”

He exhaled, steady even half-asleep. “Understood.”

I set my phone down and knelt beside my mother. Her hand shook in mine, the same hand that once shaped tortillas on Sunday mornings and folded my softball jersey back when I wanted to be as fast as the boys. “He’s still your daddy,” she whispered, and that cut deeper than anything I’d seen on patrol. I brushed damp hair from her forehead.

“No,” I said. “Tonight he’s just another man who thought he could get away with hurting you. And I don’t let men like that walk free.”

You grow up in Wharton, Texas, and you learn that the town is a stage: porch lights and picket fences and Sunday smiles like painted sets; drama whispered behind hands and broadcast across diner counters; applause for the veterans at the VFW, casseroles for funerals, rumor for sport. Folks waved at Dad on Main Street. “Good man,” they said. “Solid man.” They didn’t see the glass breaking in the kitchen. They didn’t hear the words that cut like barbed wire under the roof they’d nodded at on their drive home from church.

Mom was the kind of woman towns take for granted: hands always in flour, laugh like a porch swing, flower beds so tidy bees showed up on time. Over the years her laugh thinned. She wore scarves in June. “Your daddy works hard,” she’d say when I asked. “He gets angry sometimes. But he loves us.” I wanted to believe her. God, I did.

By sixteen, I knew better. I learned what silence costs. I swore that if it ever came to it, I wouldn’t pay that price.

You don’t become a cop without a reason. Mine wore Mom’s bruises. Mine stood in the doorway with a beer and a story and a look that made the room smaller. Leaving for the academy in Houston wasn’t running; it was breathing. Mom cried the day I left. I think she saw the shape of her own strength in mine and was both proud and afraid of it.

Now she was on my couch because the dam had finally burst.

I made coffee strong enough to strip paint and started doing what I do best: build a case. I photographed everything: the livid eye, the split lip, the marks on her wrists; the time stamp on my phone; the state of her clothes; the way her hands trembled when she reached for the blanket. She hated the lens. “Sarah,” she mumbled, turning her face. “Don’t—”

“This isn’t shame,” I said softly. “This is proof. If he denies it—and he will—this will speak louder than he ever could.”

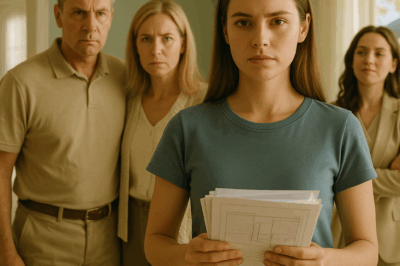

She nodded once and closed her eyes. I kept going. Bank statements tell stories men think are unwritten. A few calls later, I had his last three credit card statements: dinners in Houston that didn’t feed my mother, jewelry store receipts, hotel rooms labeled “business.” It read like a confession with a tip. I printed everything and slid it into a folder labeled EVIDENCE—CARTER.

Mom still had a few of his texts from the night before: Don’t you ever embarrass me again. You do as I say. And the one that told me what I already knew and still couldn’t read without heat rising to my hairline: If you can’t keep quiet, I’ll make sure she replaces you.

She. Denise Miller. Twice divorced. Loud laugh. Too much perfume leaving a wake down the aisle at Whitaker’s. Once I would have said she was a rumor in heels. Now she was gasoline.

By afternoon I parked at the edge of town and watched him pick her up. Denise slid into the passenger seat of Dad’s truck like she’d been practicing for it. I took pictures through the windshield. Not art. Evidence. I didn’t approach. Not yet. You don’t tip your hand before the trap is set.

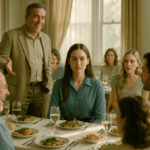

James came that evening. He smelled like old books and aftershave and a long day. I laid everything out on the kitchen table: photos, bills, texts. He went through them in careful silence, tapping the paper into order, his mouth a flat line.

“This is solid,” he said. “Restraining order, asset freeze, emergency hearing. Sarah—once we start, we don’t stop.”

“Good,” I said. “I’m tired of living in the dark.”

Mom looked small at the table. The deep purple was fading to sickly yellow now. Inside, I knew the bruise was fresh as ever. “He’ll ruin you,” she whispered. “He’ll try.”

“He’s already tried,” I said. “He failed.”

The first motion we filed was for a protective order. In a town like Wharton, news drives faster than an F-150 down Farm-to-Market 1301. By dusk, everyone at the diner knew the deputy had handed Robert Carter a stack of paper he couldn’t wrench his way out of. Men who retired from the plant with him suddenly needed something on the far side of the street. Women who’d held their silence too long stood up straighter passing him in the produce aisle.

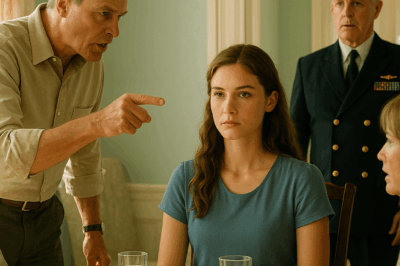

Two days later he stormed into James’s office while I sat in the waiting room. He saw me, stopped, and let his voice drop into that private register he once used to control a kitchen full of women.

“You think you’re clever?” he said. “You think your badge and your big-city lawyer will save you? You’ll always be my daughter.”

“Not today,” I said. “Not anymore.”

James pulled him into the office. I heard the shape of his anger through the thin walls—the bluster, the denial, the splinters of pride prying at something he’d never planned to examine. Lawyers are patient because paper is patient. James let him talk himself into a smaller and smaller box, then closed the lid with a few sentences and a pen.

Meanwhile, I kept digging. Denise’s debts ran like cracks across a windshield: two eviction notices, a DUI that had disappeared like smoke, unpaid bills at businesses whose owners now crossed the street to avoid being asked. Worse, Dad had signed over a small parcel to her: land that wasn’t his to give. The deed had my mother’s name where his should have been. Fraud looks fancy in script; it reads the same in court.

James’s eyes lit with something almost like relief when I slid the deed across the table. “This,” he said, “is the crack in the foundation. Now we bring down the house.”

When I met Denise outside Whitaker’s under the buzzing neon, she gave me a smile that didn’t reach her eyes. “Well, if it isn’t Officer Carter,” she said, exhaling smoke. “You got your mother’s eyes. Shame she never learned to use them. Poor thing’s been a deer in headlights since she said ‘I do.’”

I stepped close enough for her to see that my eyes were not headlights; they were high beams. “Watch your mouth,” I said. “And enjoy your nights. They’re numbered.”

She flicked ash onto the gravel with a red nail and slid into Dad’s truck when he pulled in like she owned all the air around them. Some women burn hot. Some towns go cold watching them. I went home and poured water and stared at my badge under the kitchen light until it threw a small sun on the wall.

He waited for me at his front door. The porch paint peeled in strips like unrolled lies. He filled the frame because he always had—even as he shrank. He looked at the badge first, then at my face. He said my job made me think I was better. He said Mom knew how to set him off. He said Denise gave him what Mom never could.

“Denise is poison,” I said. “You invited her to the table. That’s on you.”

“You ran to Houston to prove something,” he snapped. “You don’t know what it takes to be a man. To keep control.”

“You’re right,” I said. “I don’t know what it takes to be a man. I know what it takes to stop one.”

I handed him the folder. He opened it. Pictures fell. Receipts. Texts on white paper with black letters like a funeral. His face went the red of a man who is both angry and embarrassed. He wrapped his hand around the paper like he could make it disappear with force. That’s when I realized I was no longer the one shrinking against doorways in this house.

“This isn’t a request,” I said, turning. “It’s a warning.”

He called after me that if I walked out, I was no daughter of his. “Consider me gone,” I said, and meant it.

The countersuits came like hail: claims that Mom was unstable, that I was abusing my badge, that James was stirring trouble for a fee. The Houston lawyer my father hired wore his hair slick and his smile slicker. In town, the whispers mounted: She’s after him for attention. He’s a veteran. He fought for this country. She should handle family business in the family.

The sheriff, who had stood next to me for a photo on promotion day, pulled me aside. “Sarah,” he said, heavy with institution, “if this blows back on the department…”

“Let it blow back on me,” I said. “I’ll hold the wind.”

Mom watched it all from my couch, bruises fading while tremors returned. She apologized for the space she took up. I told her that was a sin taught to her by someone who needed room for his anger. I told her it was safe to breathe. One night she made pot roast for the first time in years. We ate without flinching at shadows. Her laugh, when it came, was small and shocking like the first daffodil through cold dirt.

Denise tried one last time to wring cash out of a man whose accounts were frozen. When she failed, she left Wharton like mist off a marsh. The night her taillights disappeared down 59, the air smelled clearer.

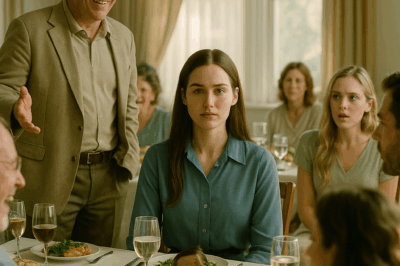

The courthouse smelled like dust and polish and public interest. Sun hit the red brick outside like a flag. The benches filled with Sunday dresses and press shirts and boots—the whole town pretending not to watch, watching anyway.

Mom wore navy and bravery. I walked her up the steps slow. My father wore the same suit he’d worn to my academy graduation, except he’d lost something you can’t tailor back on. His lawyer whispered into his ear like a vulture trading a map for a blindfold. Denise sat in the back with a smirk that said she thought this was a show. It was. It just wasn’t the one she’d expected to watch.

James stood and laid out the case the way men gut a fish: one clean cut, entrails in a neat pile, stink unavoidable. Photos. Medical records. Bank statements. The fraudulent deed. The texts projected on a screen—my father’s words big enough for even the balcony to read: If you can’t keep quiet, I’ll make sure she replaces you.

It turns out there’s a sound a room makes when a hero shrinks. It’s not a gasp. It’s a hiss—the slow leak of old admiration.

I took the stand and told the truth in cop voice and daughter words. “I’m here as a daughter who watched her father break my mother until she couldn’t hide it anymore. I did what I would do for any victim.” I pointed at him. “And he’s the suspect.”

The judge let the quiet sit like judgment before he spoke. He granted the protective order. He froze assets. He nullified the fraudulent deed. He referred assault charges to the DA. On the way out, folks didn’t look at us like a scandal. They looked at him like an answer.

Mom’s fingers slipped into mine. Outside, Texas sky stretched wide and unashamed. For the first time since the ration of my childhood ran out, I felt I could exhale without paying for it later.

Justice moves slow in boots. Charges were filed. Hearings were set. Paper piled. The mugshot hit the evening news. Folks who used to wave at Dad now found their shoelaces fascinating. Denise vanished like smoke in a brisk wind. The VFW stopped saving my father a seat.

At home, Mom got taller. She started sleeping through the night. She bought a new pair of church shoes and stood ten minutes too long in the mirror just to see if she recognized the woman looking back. She began letting people hug her long enough for it to count.

One night on the porch she said, “I thought you’d hate me. For staying as long as I did.”

I shook my head. “You survived until you could do more than survive. That’s not hate. That’s history.”

I went back to Houston and to patrol. Domestic calls cut deeper. I spoke softer. I took more pictures. I kept one promise intact: silence could win a popularity contest; it would not win a case.

Part Two

Word got around faster than formal notices: the Carters were back in court, this time under criminal charges. Wharton pretended to mind its business and failed spectacularly. Men on the square lined up like the old days waiting for a parade. Women from church wore their good pearls and carried Kleenex in fistfuls.

I put Mom in the first row. Her bruises were gone. Her courage was not. The DA, a woman with steel in her spine and a lilt in her vowels, walked the jury through the night she collapsed at my door. She brought in the ER nurse who cleaned Mom’s lip, the deputy who served the restraining order, the banker who explained the credit card statements without looking at anyone but the judge.

Dad’s lawyer tried to make me the story. “Officer Carter has an agenda,” he told the jury. “A personal vendetta disguised as justice.”

“My agenda,” I said when the DA handed me the question, “is the oath I took when I pinned on this badge: protect the people who can’t protect themselves, even when the people hurting them share a last name.”

He tried to make Mom the story: “Isn’t it true you sometimes forget things, Mrs. Carter?”

Mom lifted her chin. “Sometimes I put my keys in the freezer,” she said. “That’s not the same as forgetting what a fist feels like.”

Denise was called reluctantly. She tried to toss her hair and found it didn’t fly right in fluorescent light. The DA asked how much of the money went to dinners and rooms and gifts. Denise “didn’t recall.” The DA produced receipts. Denise fidgeted. Her smirk, deprived of oxygen, died.

Dad said he was provoked. Dad said Mom knew how to “set him off.” Dad said I was ungrateful. Dad said he was a veteran. The DA let him speak until every juror could hear the thin between the words. When he finally stopped, the DA asked one question: “Do you believe your wife is property?”

“No,” he said, plainly the wrong answer whichever way he meant it.

Juries aren’t prophets. They’re neighbors with a folder. They came back with guilty on assault. The judge added his commentary like a man who has seen too many living rooms turn into crime scenes. He sentenced probation and counseling and, because fairness sometimes wears a stern face, community service at the shelter where Mom had once dropped off casseroles.

People asked if I thought it was enough. I told them “enough” is a moving target. On the scale between silence and accountability, we’d pushed the needle hard enough for it to stick. Men who used their hands and their reputations had been put on notice.

Mom didn’t care about sentences. She cared about mornings. She cared about sitting at my kitchen table with bees in the basil outside and coffee hot enough to fog her glasses and nobody waiting to slam a door.

When the civil case over the fraudulent deed finally closed, it did so with a judge’s signature that looked like a long straight road. The land came back to Mom’s name. Denise filed nothing because filing fees require cash. Dad’s lawyer took his briefcase to a different scandal in a different county. James sat on my porch and drank sweet tea and said, “You did the hard thing.”

Mom planted sunflowers in the plot not because they match anything here, but because they turn their faces toward light. The first time one of them stood taller than her, she laughed out loud, the sound bright enough to make a moth change direction.

I thought the story might end there—with paper filed and lessons learned and the town returning to normal. But towns don’t go back; they go forward in loops. Women started turning up. At the station in Houston. At the grocery in Wharton. On my porch when the porch light burned too long. I heard, they said. Me too. I thought it was only me. I didn’t think anybody would stand with me. I kept a stack of cards by the door: James’s number; the shelter; the hotline; my own. I kept a spare room ready because sometimes the space between a bruise and a plan is a night nobody planned to spend in your house.

Mom started a Wednesday supper in the fellowship hall with the blessing of a pastor who had learned, late, that scripture is not a muzzle. women came with stories folded into their purses and unfolded them over chili and cornbread. The church ladies who had once judged dress lengths brought pies and left their opinions at the door. They named the group Second Wind. Mom wrote the words on poster board and taped them to the door and laughed when the S fell and she had to stick it back on with a bandage.

Dad did not come. He mowed a neighbor’s yard for his community service and did not show his face at the VFW. Sometimes I saw him at a distance on 59, a silhouette in a truck that used to look like a king’s chariot and now looked like what it was: a man driving home to a house that no longer let him boast with the porch light off.

I stopped needing him to say sorry. He said it once in a hallway outside a courtroom with his hands jammed in his pockets and his eyes on the floor. “I did you wrong,” he said, as if the words had been pulled out of him with pliers. It didn’t build anything. It didn’t need to. I nodded because nodding was a mercy I could afford.

A year after Mom knocked on my door at 1 A.M., the house held its breath at the same hour with a different kind of weight. The sky was clear. The cicadas were louder than the highway. Wharton slept the way towns do when the summer has finally given up fighting with fall. Mom stood in my doorway, hair in a loose braid, mouth soft with sleep.

“You’re awake,” she said.

“Couldn’t sleep,” I said. “Anniversary.”

She came and leaned on the rail next to me. We watched a cat hunt shadows in the neighbor’s yard. We listened to a train a mile away sound like a decision. Mom slipped her hand into mine. Her knuckles were still a little swollen from arthritis. Her grip was firm.

“That night I fell,” she said, “I thought it was the end of everything. It wasn’t.”

“No,” I said. “It was the end of the wrong thing.”

She smiled. Her face was not the same face it had been under those bruises. It was older. It was kinder to itself. It had learned the shape of free.

At one in the morning last year, she had collapsed at my door. I had put on my uniform. We had called a lawyer. We had started the plan. Tonight, at one in the morning, she stood next to me on a porch lit by a bulb I pay the bill for, and we didn’t whisper. Somewhere, the town stirred and turned in its sleep. Secrets that had once been passed like recipes sat under courthouse seal now, heavy as cast iron, useless for anything but teaching your hands what not to carry again.

“Sarah,” Mom said, and her voice did the thing voices do when they’re about to say something that has to land right the first time. “Thank you.”

“For what?” I asked.

“For choosing us,” she said. “For choosing you.”

The truth about revenge is that it makes bad stories. It looks like fireworks. It feels like getting your throat raw on a scream. Justice, when it is doing its best work, looks like this instead: a porch, a night that doesn’t terrify the way it used to, a woman who remembers she can laugh, a town that finally learns how to look the right way, and a daughter with a badge who keeps it on her chest and not between her and the people she loves.

If you’re carrying a secret in a town that thinks it already knows everything about you, here’s my hand. Here’s a card. Here’s a light. Knock if you have to. Pound if you must. I’ve been on the other side of that door. I know how to open it.

And if you know a Linda, be the someone she can collapse into at one in the morning. Then stand her up a year later under the same sky and call that justice.

END!

News

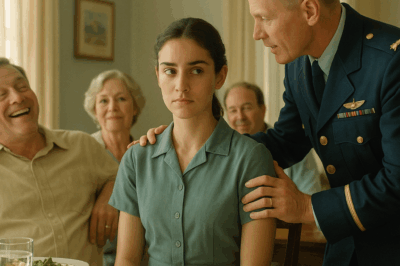

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… CH2

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… Part One My…

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. CH2

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. Part One My…

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

My Parents Demanded I Sell My House to My Sister or Be Disowned—But Her CEO Already… CH2

My Parents Demanded I Sell My House to My Sister or Be Disowned—But Her CEO Already… Part One My…

They Sold My Late Husband’s Rolex To Fund Their Luxury Vacation. The Pawn Shop Owner Called Me… CH2

They Sold My Late Husband’s Rolex To Fund Their Luxury Vacation. The Pawn Shop Owner Called Me… Part One The…

Dad Mocked Me for Studying 9 Languages—Then My Commander Said 6 Words. He Went Pale… CH2

Dad Mocked Me for Studying 9 Languages—Then My Commander Said 6 Words. He Went Pale… Part One They say rooms…

End of content

No more pages to load