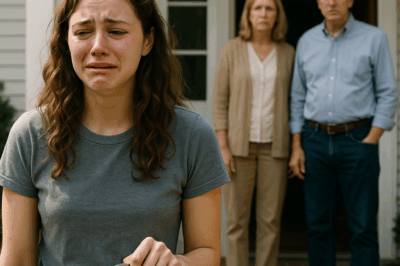

At 1 A.M., my daughter collapsed at my door—beaten and betrayed by her own husband. As both a mother and a police officer, I had to choose between silence and justice.

Part One

The porch light on my small stucco house in Riverton, Arizona hums if you listen for it. Most nights the sound fades into crickets and distant freeway noise. On the night my daughter collapsed into my arms, the hum seemed to swell, a single note holding the whole street together.

I sleep light. Two decades in uniform does that to you. The pounding at the door wasn’t like a “forgot your key?” knock. It was uneven. Scared. The kind of knock you miss once and never forgive yourself for. I was already moving before my brain finished the thought.

I unlatched, stepped back, and Lena fell forward, all bone and bruises and ragged breath, catching herself on me the way children do when they’re very small and believe you can still hold everything.

For a second, the mother won. I kicked the door shut with my hip, guided her to the couch, pressed a blanket over the shaking parts because covering is the first thing we do when we don’t know what else to fix. The officer came second, the one who catalogues as she comforts: split lip, swelling around the left orbit, defensive wounds on the hands, one arm held too tight across the abdomen. Her phone buzzed on the coffee table like a trapped fly. Threats flashed on the screen in a thread of texts from her husband, Eric.

“Don’t open your mouth if you want to keep everything.”

I wanted to throw the phone against the wall. Instead, I put a cold cloth against my daughter’s lip and counted her breaths. There is a right way to document fear. You learn that the hard way when women whisper to you behind squad cars and file cabinets because the only thing worse than what happened is what might happen if no one believes them.

My name is Sergeant Patricia “Pat” Calder. If you live in Riverton and you’ve ever watched a crowd thin after an argument in a parking lot, odds are I’m one of the reasons it did. I raised Lena in this desert town on shift work and community and the kind of stubborn love you get from women who remember hauling water before the big pipes came in. Her grandfather left her a piece of land out past the scrub and mesquite when he died. We laughed once that she’d put a tiny house out there and I’d bring over coffee every morning. It wasn’t much. It was everything.

I called Dr. Anika Patel at Riverton General from the doorway while Lena clutched my sleeve like a child again. “Anika, it’s Pat. We’re coming in. It’s my girl.”

We didn’t wait for an ambulance. Lena begged me not to make a scene. The mother in me won that round, too. A cabbie I knew by first name arrived with a thermos of something that smelled like cinnamon and didn’t ask questions.

The ER was bright and cold and indifferent the way rooms have to be when bodies get carried into them at three a.m. Anika’s face did that thing faces do when they climb from professional to personal. “Let’s get her back,” she said, no fuss, no pity.

We documented everything. Photos of every bruise with a ruler and a timestamp. Notes on the directionality of the contusions. CT to rule out internal bleeding. X-rays to check ribs and radius. A gentle exam nobody should have to narrate. We created a record that couldn’t be argued down by a man with an expensive tie and a story about clumsiness. I tucked the printed discharge summary into a folder and asked the nurse—one I’d walked to her car a hundred times on graveyards—to make sure every entry was clear. “Front desk will have copies by morning. I’ll get you a set now,” she whispered. We’d both done this before. That’s its own kind of grief.

Lena slept in the cab on the way back, then on my couch with Biscuit—my neighbor Dolores’s mutt—breathing into her hair through the throw blanket. Her phone kept vibrating. I switched it to airplane mode, the closest thing to quiet a mother can provide. I didn’t sleep. I walked the hall, stared at the uniform on its hanger, and tried to fit all the parts of myself into one body. The decision wasn’t “if.” It was “how.”

At 6:30 a.m., Riverton woke up the way Riverton always does: sprinklers ticking, one motorcycle too loud on 9th, two birds fighting over one piece of toast someone dropped from a truck. Dolores was already sweeping her front step. She stopped, broom mid-air, and bee-lined across the gravel. “You okay, Pat? I heard—” She didn’t say the word. She didn’t have to.

“It was Lena,” I said. “He put hands on her.”

Dolores’s mouth flattened. “That boy never knew how to stand up without stepping on a person.” She lifted her phone. “My porch cam caught her coming in. You can have it. And if you need me to say what I saw under oath, I’ll wear my good shoes.”

The video was brutal because videos are about truth, not kindness. Ten-oh-two p.m. Lena’s figure on my porch, shoulders hunched, knocking like she was afraid the noise would wake the world. The footage wasn’t just proof she arrived. It was proof she was scared. I saved it three places: the cloud, a drive in my office, and one copy on a thumb drive tucked under the sugar canister like I was living in 1973 and not 2024. You don’t put all your eggs in one legal basket. Ask anyone’s grandmother.

By mid-morning, the first rumor made it to my sidewalk. “I heard Pat’s girl started it. Those girls from the river houses, they drink too much and—” I closed my door. People will say anything to avoid looking at their own reflection.

At eleven, my phone buzzed with a number I knew from a hundred dull meetings that had saved a thousand headaches. “Pat? It’s Caleb from records.” He’s the kind of man whose tie is always crooked and who keeps three different kinds of candy in his desk for the kinds of days that need them. “A transfer came across my desk with you and Lena on it. Something about your land. It didn’t…smell right.”

“Tell me everything,” I said.

Caleb slid a manila folder across his counter half an hour later. I didn’t touch it right away. Paper can bite.

“Transfer of deed,” he said. “From Lena Calder to a ‘Tara Quinn.’ Filed by Eric Maddox. Two notarizations. The notary on the stamp wasn’t on duty that day. Signature looks like it was written left-handed by someone who’s never held a pen.” He cleared his throat. “Says here you signed as witness. I been to your Sunday barbeques, Pat. You don’t scrawl like a doctor.”

He handed me certified copies before I could ask. “Watch your back,” he murmured. “Somebody inside slid this to the top of the stack.”

Land records have gravity. The weight of the paper felt like my father’s calloused hand on mine the first time he showed me the markers he’d put out on the edge of our property. He worked a thousand days to buy that dirt and Lena cried when she learned we’d put her name on it. She wanted to plant mesquite beans and sell flour at the farmer’s market. We talked about building a little one-room thing with a porch big enough for two rocking chairs.

I folded the copies back into the folder and drove to Mallory Trading Post because if you’re going to look a man in the eyes and tell him where the line is, it helps to do it where other men can vouch you did.

Eric kept his office door open like he thought it made him look legitimate. The pawn shop counter smelled like old brass and bad cologne. His friends leaned against the glass and looked at me like I was the joke you tell without the punchline.

“Sergeant Calder,” he said, almost purring. People who roll their r’s like that usually hide thick tongues and thin skin. “Looking for some jewelry? I got some nice pieces. Trade-in program’s real friendly.”

I put the folder on his desk and opened it like a tent, each page a stake in the ground. Hospital photos. ER report with Dr. Patel’s signature and date and time. Still shot from Dolores’s camera with metadata time stamp in the corner. Three pages of threatening texts from his phone number to Lena’s, the words “keep quiet or else” typed by a man who believes his words make laws.

His eyes flicked and twitched, then landed on the deed. Something ugly crawled across his face and flared his nostrils. “You bringing me scrap, Pat?” he said. “You know this is a personal thing. Don’t bring your badge into family business.”

“I’m here as her mother,” I said. “The badge comes later. So does the law.”

He leaned forward and smiled the way a dog does when it thinks it might bite you soon. “Girl needed a lesson. You cops can’t always make up crimes to keep busy. I got lawyers. She’s got daddy’s dirt and a lot of crying.”

“You’re right about one thing,” I said, gathering the papers in a slow, calm motion that made him lean back. “You do have lawyers. You’re going to need better ones.”

I walked out with his friends calling something about “thin blue line” after me that made me laugh all the way to the truck. Men like that always think their loud is louder than your quiet.

By sunset, all of Riverton knew something had happened. The rumor had grown legs and given itself a name. At the grocery store pickup, I heard “Pat’s just mad because her girl married a man and moved out” whispered by a woman who hadn’t moved in twenty years. At the diner, I heard “girls in uniform forget their place” said by a man who still wore his class ring like it owed him rent.

When I got home, there was an envelope shoved under my door without a stamp. It smelled like cheap hand soap and cigarettes. Inside, two words: “Shut up.” Below them, one sentence: “Or you’ll lose your daughter.” The letters leaned to the right like a man who walks too fast in one direction for too long. I slipped it into a Ziploc and wrote the date on the outside with a Sharpie. Fear is evidence when you do it right.

I called Captain Ramirez because when you carry a badge, you give up the luxury of private wars. “Joel,” I said. “I need two extra passes on 300 South tonight and eyes on Dolores’s house. And if Eric’s boys are on duty, they’re off.”

“You’re right about the last part,” he said. “And Pat? I’m sorry. We’ve got your back. Keep it clean.”

I did not sleep. I took my uniform off the hanger and set it on the back of a chair. Some nights you put it on to be taller than you feel.

The next day, I went hunting because truth costs you extra steps.

Every rumor has a seam. You pull at it and sometimes you unspool the whole garment. The name on the fraudulent deed had weight: Tara Quinn. She worked nights sometimes at the Silver Spur, the bar at the edge of town that makes good tacos and bad decisions. She was there just after ten in a red dress and too much fear in her eyes. I asked the bartender for water and a lemon straight. He winked, set it down, and slid a napkin onto the bar. “On the house, Sarge,” he said. “For table six.”

I set an envelope down in front of Tara and slid it with one finger. She looked at it like it might be heavy and she wasn’t wrong. When she opened it, her face changed three times in two seconds.

“He said the land was mine,” she said. Not defiant. Lost. “He said she didn’t want it. He said—he said I’d get a cut if I helped because…because I’ve been good to him and—” Her voice buckled and straightened. “He’s been paying some of my bills. I thought…” She swallowed something jagged. “I thought it was a way out.”

“People who promise you land in writing don’t hand you a notary stamp on a photocopied page,” I said. “People who hand you fake papers make you a fall guy. You’re not a guy. I don’t want you to be a fall.”

She stared at the last page, the case note from records that indicated a clerk had pushed the deed through fast. The bar lights flashed blue on the slick paper for a single second—reflected TV, one of those crime shows that look like my job and don’t feel like it—and when it passed, Tara looked older and more honest.

“What happens if I tell the truth?” she asked.

“You get protection and maybe a clean start,” I said, not lying even a little. “You get to walk out of whatever this is with both feet planted. You get to skip the part where he throws you under the bus he’s been promising to drive.”

She nodded. Small. Then bigger. “Okay,” she said. “Okay.”

My attorney is named Marcus because of course he is. He wears suits like he was born in them, but he cussed when he heard the story and asked for a coffee that wasn’t out of a machine. We spread evidence across his conference table like a family holiday: ER records, photos, the video of Lena at my door, the text thread that made my hands itch, the deed with the drunken signature. He tapped each item like it was a nail and I was building a fence. “Exhibit A. Exhibit B. Exhibit C. Exhibit D.” He smiled without humor. “We have a case.”

We filed a protective order and got it inside twenty-four hours because paper can be faster than time when you have a judge who remembers you from Thanksgiving food drives. The restraining order was temporary but thick. Eric was legally blind to my address and Lena’s location. We put Lena at Dolores’s spare bedroom for three nights, then moved her to a safe apartment city volunteers keep filled with clean sheets and dignity. I saw that he had been served because I made sure to drive past his shop the hour I knew the papers were delivered. He threw a folder at a wall. It was empty. That thrilled me in a way I’m not proud of.

Riverton’s courthouse has six benches and air that always smells like stale paper and old air-conditioning. The morning of the hearing, every bench was filled with people who have opinions about my life. I like to think most of them are kind. The rest can eat sand.

Eric wore a suit like he was borrowing it for a funeral. His lawyer, a man with hair slicked back so tight I worried for his skin, stood and made a speech that sounded like a bag of snakes being shaken. “Family dispute,” he said. “Overzealous mother with a badge. Alienation. Gold digger. Dirt poor melodrama.”

Marcus stood and unrolled our case like a blueprint. He didn’t use big words. He used timestamps. He used Anika’s signature and Dr. Patel’s calm voice and the way the bruise on Lena’s rib matched a ring on a man’s hand. He called Dolores because the truth loves a neighbor. Her porch camera footage played on a projector screen crooked on a cart. You could hear Lena say “Mom” through the glass. People put hands to mouths as if to hold in disbelief. They should save that shock for things that aren’t the obvious consequences of a thousand unchecked red flags.

Caleb from records explained notary stamps like a priest explaining communion. “The stamp used was not logged. The signature does not match. The notarization date is a Sunday. We aren’t open on Sundays.” He shrugged. Simple. Devastating. Rural truths are like that. Then Tara took the stand and traded the last of her shame for a future. She told the truth without sugar. “He said he’d give me land if I signed because she wouldn’t fight. He said a lot of things.” The judge watched her with the eyes of a man who has seen every version of a woman making a decision on a witness stand and knows which ones change a life. This was one.

Eric stood up and called her a traitor. You could feel the room pull back from him like he smelled wrong. The judge pounded his gavel once. Men like Eric respect hammers they can see.

Then it was my turn. I wore my uniform because I own both of my names and this was not a shift to be ashamed of.

“I am a police officer,” I said. “But I am here as a mother. The law is supposed to serve us when we are broken. Tonight it makes me both the plaintiff and the proof.”

Eric’s lawyer tried to insinuate, to imply, to suggest and massage the facts into a pillow that would allow his client to nap through consequences. Marcus objected exactly often enough to remind the room where the lines were. The judge listened like I wish the world always did.

He took a recess that lasted nine minutes and came back with a face like someone who knows the exact time a door should close.

“Protective order granted,” he said. “Deed nullified. Assets frozen pending further action. Case referred to the district attorney for domestic violence and forgery charges. Any violation of this order will result in immediate remand.” The gavel was a punctuation mark, not a weapon. Eric sagged just enough to remind me he was not a story. He was a man who had run out of other people’s free passes.

They cuffed him. The metal click sounded like the first honest thing he’d heard all week.

In the hallway, Lena shook for the first time that day and then breathed like she had crossed a river. I put my hand around the back of her head the way I did when she was five and had a fever. She was twenty-six and she still fit inside my reach.

Healing is a crooked road. Sometimes it looks like counting four green things in a room so your brain remembers where it is. Sometimes it looks like Dr. Naomi Winters teaching you how to breathe through memories so they stop running you ragged in the dark. Sometimes it looks like going to a grocery store and not seeing monsters behind a stack of canned tomatoes. Sometimes it looks like driving past a pawn shop and not ripping the steering wheel clean off.

Lena made a list and put it on the fridge. Small things. Walk around the block. Make Mom’s chicken and dumplings and eat two bowls. Call Grandpa’s brother and ask him about the story with the horse again. Imagine the porch on the land in spring.

I made a list, too. Go to work. Keep your temper. Keep copies of everything. Look for women in the eyes on calls. Hand out cards that say more than “good luck.” Teach rookies what it means to write reports like their own mother will read them one day.

I also started a new thing because flags planted in the ground are useful only if you check on them now and then. We called it the Second Porch Fund because when your first porch breaks, you need another place to sit and breathe. Women showed up with boxes and bruises and a look that said “I am tired of being tired” and a hundred volunteers showed up with crockpots and bunk beds and legal contacts and a willingness to drive across town at 2 a.m. and sit outside an apartment building while someone grabbed their papers and their photographs before a man could call “police” and mean “cover.”

Rebecca donated once. So did Ashley. So did Dolores because women like her have been saving this town since the town forgot how to do it. We put a plaque in the entryway: For those who knock in the night. The light is on.

Lena moved back into my house for a while. She slept in the room with the ugly floral wallpaper she used to hate. She paid for groceries because respecting boundaries means following rules even when you’re hurting. She cleaned the bathroom before I asked. She sang along to the radio again when she thought I wasn’t listening.

She went out to the land on a Saturday in March, stood in the wind, and said “thank you” to a man who had been dead ten years for giving her a place to stand. She staked out where the porch would go. She planted two mesquite trees and a violet because her father loved those and because healing looks like digging holes and filling them with something that will grow long after you are done being proud of yourself for planting anything at all.

Eric pled to a lesser charge on one count and went to trial on another. Lena didn’t attend every hearing because she doesn’t owe the court her suffering. She read the documents with a finger pressed to the page like she used to read storybooks on my lap. She asked me if I thought forgiveness was required to grow a future. I told her forgiveness is a gift you give yourself, not a favor you give a man who needs to go find a shovel and dig out his own rot.

A year to the day after Lena knocked on my door, the mesquite at the corner of her small house had a leaf and the porch had two chairs because I know how to make things level and she knows how to make choices. We sat and watched a coyote nose around the empty lot next door. She touched the place on her arm where the bruise used to be because memory is tactile.

“You did it,” I said.

“We did it,” she answered, because corrected memory is its own kind of justice.

People in town still talk. They say I used my badge to ruin a man; they say I used my mother heart to lie professionally. They say I did what I had to do because some men cannot help themselves. The truth is simpler than gossip and twice as boring: I wrote things down. I took pictures. I asked for help out loud. I built a case like a house and then I opened the door for my daughter.

If you are standing in your own kitchen right now with a phone that hurts to look at and a bruise you aren’t ready to name, here are small, legal, practical things:

– Write the date on a piece of paper and take a photo of your injury next to it. Email it to an address you can access from a library computer if you have to.

– Save texts. Do not answer bait. Forward them to a friend for safekeeping.

– Go to the ER. Use your name. Ask for a copy of the discharge summary. Ask them to photograph injuries. They will if you ask.

– Check property records online or at your county clerk’s office. If a signature looks wrong, get certified copies. People who commit fraud like to think ink is a cloak. It isn’t.

– Tell one neighbor whose porch light you’ve always noticed. People who sweep in the morning will swear on a Bible in the afternoon.

– Call. The number you already know or the one you look up right now. You don’t have to be a police officer to use the law. You only have to be tired of silence.

When I put my uniform on the morning after that night, it wasn’t for war. It was because a badge is a promise you either keep or you don’t. Choosing justice over silence didn’t make me less of a mother. It made me the kind of mother who remembers what the law is for.

We are not done with this story. Women rarely are. But the ending we have is clean enough to set down and walk away from without looking back every five steps.

We replaced the porch light at my house with a motion sensor last week. It flicks on when you move right and stays off when you stand still. Lena says it makes her feel watched and safe at the same time. I say that’s all I ever wanted to give her.

The night is quiet again. The hum is back to normal. Somewhere across town, boys with loud bikes lean into curves they’ll straighten out when they’re older. On my porch, a violet blooms in a chipped mug. On my daughter’s land, a porch holds two chairs and a shadow where the afternoon sits down and stays a while.

If you’re watching from a city I’ve never been to, tell me its name. Tell me if your night is loud or quiet. And if you need to knock, knock. The light’s on.

Part Two

By the time the desert sun bled into the mountains that next evening, the order of protection had been served, my evidence binder was thick enough to bruise, and I had done the thing that keeps you honest in a small town: I walked into my own captain’s office and handed over my badge.

Not to quit. To declare a line.

“Administrative assignment only,” I said, setting the leather on his desk with the same care I use for my sidearm. “No direct contact on the case. I’m a witness on one side and a mother on the other. I can’t be the officer in the middle.”

Ramirez studied me for the space of four breaths and then nodded. “You’re doing this right.” He slid the badge back toward me. “Keep it. Work your hours behind a desk until the DA is done with Eric. Let the process be the process.” He leaned back. “And let me be the one who explains to anyone who asks that we protect our own from conflict and from cowards. Both.”

When I stepped into the hallway, Detective Sheryl Gomez was waiting, one hand on a file, one foot already heading toward the grind of the job. Sheryl’s the kind of detective who can read an empty coffee cup like a witness statement. She squeezed my forearm as we passed.

“I’ll carry it,” she said. “The case, I mean. You carried her. Let me carry this.”

The DA moved faster than I expected—faster than rumors can adjust their hair and go for coffee. Four felony counts: aggravated assault causing serious bodily injury, fraud, uttering a forged instrument, and witness intimidation. Three misdemeanors for violations of the protective order. Plus a pile of enhancements that meant what they were supposed to mean: if you make a community less safe, the community will make you smaller for a while.

Eric pled not guilty at arraignment and glared at me in the hallway the way a boy glares at the belt on the wall. Tara didn’t come that day. She had the shakes that week, the kind you get when you stop believing lies and your body runs out of adrenaline to keep you upright. We’d put her up with a friend of mine who runs a trailer park on the southeast edge of town—man with four hound dogs and a heart big enough to house a football team. She learned that morning how quiet the desert can be when a man isn’t yelling. It made her cry. Quiet often does at first.

Two days later, Internal Affairs called me into a little room with gray carpet and a plant that has seen too much. IA isn’t your enemy when you do the job right. They’re the ones who make sure your reflections add up.

Sergeant Dwyer sat with a tape recorder and a face like patience. “Pat,” he said, “things move faster when it’s one of us. Faster and sharper. You know we have to ask.”

“I know,” I said, hands flat on the table. “I didn’t touch his shop as a cop. I didn’t log in to anything I shouldn’t. I didn’t flash the badge. I did what any mother with a filing cabinet and a clock would do: I documented my world and handed it to a lawyer.”

He clicked the recorder on. The red light blinked steady as a heartbeat. I repeated the dates, the times, the places. I admitted that it shredded me to say some of it with the same tone I use for traffic stops. He asked about the porch camera.

“Voluntary,” I said. “Dolores trusted me with it because I’ve walked her to her car at midnight for ten years.”

He nodded. “You didn’t intimidate a witness?”

I thought of Tara in her red dress, how the light caught in the rim of her glass and made a small halo on the bar top, and how I put a copy of the forged deed in front of her like a clean path. “I let the truth do the talking,” I said, and Dwyer nodded again, clicked off the recorder, and smiled with the corners of his eyes the way tired men do when their job is to wear the worst stories long enough to see daylight peel them off.

“You’re clear,” he said. “Go back to your desk. Answer phones. Write reports. Eat the donuts that come from the shop by the courthouse because the ones from the other place taste like disappointment.”

I brought donuts to the clerk’s office the next morning and left them without a note. Caleb pointed a jelly at me anyway. “This will make me testify faster,” he said, smiling around powdered sugar.

If you’ve never prepped for a felony trial, imagine knitting with dental floss while people you barely know try to pull at the yarn from three directions. We met in Marcus’s conference room every other day, stacks of paper like sandbags around the table, highlighters bleeding neon into the clean margins.

“Order of witnesses,” he said, tapping the list with his pen. “We start with Dr. Patel because juries understand medicine. We go to Dolores because juries understand neighbors. We bring in Caleb because signatures look like lies or truth. We call Tara when we’ve built a scaffold strong enough to hold her weight. We end with Lena because this is her story and juries understand daughters. We do not call you until they make you talk. You are a sledgehammer and a mother and we use both only if they try to throw stones.”

I nodded. Lena sat next to me with a blanket draped over her lap in August like a talisman. People in trauma draft their own rules for temperature. I did not tell her to take it off.

We practiced questions. We practiced answers. We practiced silence. Not every silence is a weapon; some are shields. Lena learned to breathe in threes and answer in ones.

When the grand jury indictment came down, Eric’s lawyer tried a new story in the press: “Vindictive mother-in-law. Hysterical women colluding to steal a man’s property. Mistakes on a deed, not malice. Bruises from a fall, not a fist.” Reporters who don’t come to the west side unless something is burning camped at the edge of our block and took photos of my porch light. I flipped it on and off twice and then went inside and made coffee like I didn’t hear my name mispronounced two times in a row.

In the midst of this, my phone rang one afternoon with an unfamiliar number from the capital. “Sergeant Calder?” the voice asked. “This is Assistant Attorney General Vee Nguyen. We received a referral from your DA’s office about possible corruption in the recorder’s office.”

“The stamp?” I asked.

“The stamp,” she confirmed. “And an email chain that suggests an employee expedited filings for a fee. Your case is one of four.”

“Caleb’s good,” I said, thinking of the crooked tie and the candy. “Don’t grind him.”

“We won’t,” she said. “He’s a witness. The rot’s above him. You put this in motion.”

“I just kept my eyes open,” I said.

“Not just,” she replied, and hung up.

Trial prep did something to Lena’s voice. It made it smaller for an hour and bigger later. It taught her the weight of a pause and the mercy of a full sentence. She got so good at saying, “I’m not sure” when she wasn’t sure that I wanted to pin a badge on her chest that said “Officer of Her Own Mouth.”

Two weeks out, we drove to the land right before sunset and walked the wash the way my father did the day he planted the first mesquite. The air tasted like warm pennies and dust. Lena bent and put her hand on the ground.

“If I had lost this,” she said, “I would have lost more than dirt.”

“You’d have lost the place you stand in your head,” I said.

She laughed once. “You talk like Grandma,” she said.

“Good,” I replied, because Grandma raised two people who told the truth for a living.

She took her shoes off and stepped into the dry wash like it was a rite. “When it rains,” she said, “we’ll bring chairs out and watch the water run. We’ll do it the old way and say a prayer for whoever is downstream.”

“You’re going to be okay,” I said.

“I’m going to be loud,” she answered, which is a different kind of okay but sometimes more useful.

The day before the first day of trial, a note showed up at Dolores’s door in a plain envelope again. “You think a court can save you? We know where you sleep,” it read. The handwriting slanted tired and fast. Dolores brought it to me tucked inside her Bible like she thought the psalms could make ink behave.

“We ask for bond conditions to be tightened,” Marcus said, not looking up from his screen. “We ask for electronic monitoring. We ask for a curfew. We ask for sanctions for his clients if the lawyer doesn’t stop using the paper to try the case.” He looked at me finally. “We make the courtroom the only place any of this happens.”

The judge agreed. The ankle monitor beeped twice when they fitted it around Eric’s sullen silence. His lawyer looked mad in a professional way, which is to say he still got paid.

Trial.

You learn fast which benches creak, which jurors bring snacks, which bailiffs prefer you to stand two feet left when you speak. You can feel which way a room leans the way you feel where the shade starts in August.

Marcus set his easel up like a schoolteacher. “Domestic violence is a pattern,” he said in opening. “Not a single blow. Violence against property. Violence against paper. Violence against peace. What you are about to see and hear is a story made of small truths that add up to a large one.”

He did not say Eric’s name with anything other than breath. He saved adjectives for papers and dates and X-rays. When Dr. Patel described Lena’s injuries, she did it like she was describing the weather. Juries believe the weather. Her fingers hovered over the photos projected on the wall and landed on the edges so she didn’t touch the pain. The defense tried to get her to say “possibly” and “maybe.” She said “unlikely” and “no.” The words held.

Dolores told the story of hearing the knocks. She wore a pressed blouse and the shoes she promised and sat straight like a woman who has buried two husbands and knows what real grief sounds like. She cried once. She did not apologize.

Caleb talked stamps and logging and dates. He brought a three-ring binder with records that made the defense attorney look like he had indigestion. “We’re closed on Sundays,” he said again. “We’ve been closed on Sundays for twenty years. The stamp says Sunday.” He held up his hand. “Math is math.”

Tara stood with her hand on the Bible and told the truth with a wobble. Eric whispered something obscene. The bailiff said “Sir” in a tone men like Eric don’t hear very often and he shut his mouth. Tara’s testimony was a bridge. The jury walked across it like people who have been waiting their whole lives to see a woman choose the right river.

Then Lena. She wore a navy dress she hated and the earrings her grandfather bought her in Santa Fe when she turned sixteen. She did not make herself small. I watched her anchor herself with the loop of her finger through her bracelet and the way she pressed her toes down inside her heels like she was grabbing the carpets with bare feet.

Marcus asked plain questions. She gave plain answers. She didn’t make Eric a monster. She made him a man who does harm. That distinction matters. Monsters can’t be stopped. Men can.

The defense tried to make it about us—her mother the cop, the badge on the chair two rows back, the blue threads woven through our town the way irrigation runs under fields. “You ever talk to your mother about your marriage?” he asked, as if that were a crime. Lena smiled in that small way that looks like breathing.

“Every girl talks to her mother,” she said. “But my mother didn’t make him hit me.”

You could feel that sentence settle onto the jurors’ shoulders like a cool cloth.

When it was finally my turn, Marcus kept it short because he understands how long truth can stand up before it needs to sit.

“Sergeant,” he said, “what did you do the night your daughter knocked on your door?”

“I opened it,” I said.

“What did you do the next morning?”

“I opened the file,” I answered.

“What did you do in court today?”

“I opened my mouth,” I said.

The jury smiled like they’d been allowed to.

The jury came back in three hours flat. Guilty on three felonies, one misdemeanor. Not a perfect sweep. Courts never are. Justice isn’t a haircut. It’s a weather pattern.

Sentencing came a month later with a pre-sentence report so thick it made the clerk swear under her breath when she carried it. The judge spoke slowly.

“The desert teaches that there is a difference between heat and light,” he said. “You have offered this community the first without the second. You brought harm. We bring consequence.”

Three years in state prison on the aggravated assault, five years probation on the fraud count to run concurrent with restitution to be calculated, twelve months on the intimidation to run concurrent, the misdemeanor merged into the rest like a warning folded into the bigger paper. Bond revoked. Immediate remand. Anklet cut, handcuffs clicked, door swung closed like punctuation.

There was no cheering. There never should be. Lena squeezed my hand. The bailiff nodded at me in that way professionals nod across rooms when the story is too heavy to carry alone.

He appealed. They always do. He got nowhere. Appeals are the part of the river that looks still and moves faster than people think. In the meantime, the Attorney General’s office indicted a deputy recorder and two middlemen for the stamp business. The news did what news does: ran the mugshots big and the follow-up small. Caleb got a commendation from the county supervisors that came with a photo of him shaking a hand and a gift card to a steakhouse. He framed the photo and gave the gift card to his mother.

Tara moved to Tucson with a new phone number and a job at a diner where nobody cares who you used to drag on your arm as long as you bring coffee hot and smile when someone’s jokes aren’t that funny. She sends a postcard every few months. “Still telling the truth,” she writes. “Still standing up.”

Dolores brings a loaf of lemon bread every Friday because that’s how she prays. “For the women who knock,” she says, leaving it on my countertop like a blessing.

Lena built her porch. Two chairs. One for me. Her mesquites grew thicker; she planted wildflowers in a ring she called “the halo” because sometimes you name things to make them bigger than the hurt that used to fill the space.

The Second Porch Fund opened its third house over on Redwood. The ribbon cutting smelled like coffee and cinnamon and a little bit like paint. Judge Ellery (I can call him Marcus in my head; I do not in public) gave a speech about community that made two people cry and three more sign up to volunteer sitting overnight in the intake room. Sheryl donated a bookshelf and a stack of paperbacks with post-its on the first page that said “Choose any life.”

One night, a girl barely old enough to drink knocked on the shelter’s door at two a.m., her eyes wide the way you get when the rearview is as scary as the windshield. She held a duffel bag and a dog that looked like it had been living on pretzels. She wore a shirt that said “I have decided to be difficult.” I loved her on sight.

“Who sent you?” I asked, keeping my voice the way I wish every officer had talked to me the night I learned the sound of my daughter’s voice when it breaks.

“A woman at the diner,” she said. “Said ask for the porch light. Said somebody here keeps it on.”

I let her in. That’s the whole story some nights. The rest is logistics and casseroles and court dates and paperwork and a dog sleeping at the foot of the bed because faithfulness is loud when everything else is quiet.

People will ask if Lena forgave me for being a cop that week as much as a mother. She did. She does. Forgiveness in our house looks like her leaving coffee for me when I’ve written three reports in a row and my hands ache; it looks like me knocking before I walk into the bedroom she turned into an office because she remembered all by herself that it’s okay to take up space.

People will ask if Lena forgave him. That’s not mine to answer. I will say this: she forgave herself for staying as long as she did. That’s the hardest part, and she did it with a therapist and a notebook and mornings where the only thing on the to-do list was “keep going.”

People will ask if I regret anything. I regret all the days I told myself she was just tired when she was really scared. I regret the times I believed the smallness of this town’s talk instead of the largeness of my daughter’s pain. I regret not planting the mesquites sooner, both the real ones and the kind you put inside your chest to throw shade on yourself when the sun is cruel.

But I don’t regret opening the door. I don’t regret opening the file. I don’t regret opening my mouth.

A year and a day after Eric went in, Lena locked her front door, turned around, and saw me leaning on her fence. We didn’t plan it that way; we just kept ending up in the same place at the same time, which is what family looks like when you do it right.

“I can feel it,” she said, spreading her hand against her sternum.

“What?” I asked.

“The quiet,” she said. “The good kind.”

We sat on the porch and drank coffee hot enough to scald the part of your tongue that tells you when to stop talking. We watched a rabbit consider whether my truck was its enemy. We listened to the breeze move across the scrub like somebody rubbing a thumb over coarse fabric.

“You taught me to call 911 for other people,” she said. “I didn’t think I could call you for me.”

“You knocked anyway,” I said.

She looked at the porch light like it was a friend. “Thanks for keeping it on,” she murmured.

“Always,” I answered. And I meant it.

If you find yourself holding a phone and a bruise and a choice, I cannot promise you the desert will be kind. I cannot promise you the courtroom will feel like church. I cannot promise you your neighbor will have a camera or your doctor will have the exact words or your clerk will notice the stamp is wrong. I cannot promise you an assistant attorney general will call your phone and tell you that your case was one of the ones that showed her where the rot is. I cannot promise you that the judge will see you. Some men in black robes see only paper. Some see people. The law is a map. Not everyone reads it well.

What I can promise is what I chose the night the knock split my house into then and now: you are not wrong to open the door. You are not wrong to write it down. You are not wrong to ask for help with your hands shaking. You are not wrong to put your uniform on, whatever yours looks like—a badge, an apron, a name tag, your own skin—and say “here is my daughter” and “here is my hurt” and “here is the truth.”

The porch light at my daughter’s new house hums the way mine does. We swapped out the bulb last week because it flickered and she worried some lost woman might think that meant the welcome was wavering. It isn’t. Not at my house, not at hers, not at the shelter with the lemon bread on Fridays.

If your night is loud, I hope it gets quiet. If your night is quiet, I hope it stays soft. If you knock, we will open the door.

The light is on.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Mother-In-Law secretly recorded me for three months, claiming I was a terrible wife and destroying her son’s life. CH2

My Mother-In-Law secretly recorded me for three months, claiming I was a terrible wife and destroying her son’s life. …

The Silence Of My Parents Hurt Worse Than Her Words—They Let Her Crush Me. CH2

The Silence Of My Parents Hurt Worse Than Her Words—They Let Her Crush Me. Part One The room was…

She laughed in my face, claiming i was never legally married to her son. CH2

She Laughed in My Face, Claiming I Was Never Legally Married to Her Son Part One When people talk…

Why do you hate your parents? CH2

Why Do You Hate Your Parents? My parents kicked me out for getting a job and not being able to…

The Day My Parents Kicked Me Out With A Suitcase… Was The Day The Lottery Hit. By Dawn, I Was Rich. CH2

The Day My Parents Kicked Me Out With A Suitcase… Was The Day The Lottery Hit. By Dawn, I Was…

At Brunch, My Mom Smirked “You’re Lucky We Even Include You—Pity Goes A Long Way. CH2

At Brunch, My Mom Smirked “You’re Lucky We Even Include You—Pity Goes A Long Way” Part One They chose…

End of content

No more pages to load