After the wedding my daughter-in-law showed up at my door with a notary we’ve just sold this house…

Part 1

After the wedding, my daughter-in-law showed up at my door with a notary.

“We’ve just sold this house,” she said, voice bright as tinfoil. “You’re moving to a nursing home.”

I looked at the stamped folder in the notary’s hands, at the realtor’s SOLD sign I could now see through the front window, at the woman my son had married. Then I set my tea cup down, very gently, as if I were placing a bomb.

“Perfect,” I said. “On the way, let’s stop at the police station. They’re very interested in what I sent them about you.”

Madison’s smile faltered. It didn’t disappear—she’d been practicing that smile for thirty-two years—but a hairline crack appeared at the corner of her mouth. The notary, a pale man with nervous eyes and a tie knotted a little too tight, shifted his weight.

I’ve outlived three sisters, one husband, two breast tumors, and a rollover on I-95. I have buried more people than Madison has cooked dinners. At sixty-nine, I am not so easily moved.

Two days earlier, I’d watched my only son, Ethan, marry Madison in the same church where his father and I said our vows forty-one years ago. The sanctuary smelled like lilies and lemon-scented polish. The new pastor kept talking about beginnings; I kept hearing echoes.

Madison was gorgeous, in that curated Instagram way—ivory dress shimmering, hair swept into the kind of chignon you don’t risk in real life. She glowed. Ethan looked like somebody had removed a weight from his shoulders and replaced it with helium. I held my clutch in both hands so they wouldn’t see them tremble.

I had tried to like her. God knows I had. When Ethan brought her to Thanksgiving three years ago, she’d marched into my kitchen with a bottle of five-ingredient organic cranberry juice and told me she loved “traditional food with a modern twist.” She spent most of the day “taking calls for a client” and the rest scrolling while I basted the turkey. At dinner, she said the stuffing was “so nostalgic” in the same tone other people used for “so unsanitary.”

But, I told myself, I’m not marrying her. Ethan is. And after Michael—my husband—died, I’d watched my son drift through two years of half-hearted dates and late nights at work, his energy flat, his eyes dull. Madison made him laugh again. That counted for something.

The wedding reception was at the country club on Maple Ridge, the one I used to clean bathrooms at in my twenties when Ethan was small and our rent was bigger than our paychecks. Now I walked in wearing a navy dress I’d bought second-hand and altered myself, watching chandeliers throw light on people who’d never scrubbed a toilet that wasn’t theirs.

The toasts were what you’d expect. The best man told a story about Ethan fainting in eighth-grade health class. Madison’s sister cried on cue. I sat at a round table with two of Ethan’s coworkers and a couple from Madison’s cycling class, who said things like “We just love her energy” and “She’s such a boss.”

When Ethan clinked his glass, I braced myself. He smiled at Madison, then at the crowd.

“I just want to thank everyone who helped us get here,” he said. “My beautiful wife, our friends, and my mom, who has always been there when I needed her.”

Polite applause. I blinked hard. My heart did the little flip it still does when he remembers I exist.

Then Madison stood up.

“I want to say something about Mom, too,” she said, one manicured hand on my shoulder as she passed behind my chair, the other resting casually on her stomach. The room hushed.

“She’s been living with us for months,” Madison said, smiling at our guests with the well-practiced warmth of a realtor about to close. “Helping with…well, everything. I’ve learned so much watching her. A lot of mothers step back when their sons get married and start their own lives. But not Ruth.”

A strange murmur rippled across the table. I could feel people recalibrating—wait, the groom’s mother lives with them?

“She’s taught me that a real mother never stops taking care of her children,” Madison went on. “She cooks, she cleans, she keeps track of everything. She even helped with the down payment on our house. She says it’s just what mothers do, but I know it’s more than that. It’s sacrifice. It’s love.”

There it was. Wrapped in sugar, slipped like a knife.

None of that was technically untrue. I had moved into their guest room six months earlier. I did cook. I did keep track of things, like which bills were late and how many times Ethan forgot to eat dinner. And I had given them twenty thousand dollars for the down payment on their house—the rest of my savings, carefully accumulated over years by working double shifts at the grocery, skipping vacations, and driving a Corolla with 189,000 miles on it.

But in Madison’s version, I was a permanent appendage, a woman without a life who lived to take care of her son. In hers, the twenty thousand was not a loan we had carefully discussed and put in writing at my kitchen table; it was a gift, an open vein.

I smiled at my folded hands and stared at the ring Michael had given me on our fifth anniversary. I imagined the stock pot on their stove, the chipped rooster mug in their cabinet. I added resentment to my list in my head, right after cinnamon and salt.

After the reception, after the first dance and the cupcakes and the group photos on the lawn, I went back to their three-bedroom house on Oakview Lane and took off my shoes in the quiet. The hallway smelled like fresh paint and Madison’s perfume—peony and something sharp underneath.

She came in a little later, barefoot, high on attention.

“Did you like my speech?” she asked, leaning in my doorway as I hung up my navy dress.

“It was…surprising,” I said carefully.

“Oh, come on,” she laughed. “You were amazing. People think it’s so sweet that you’ve been helping us. They’re jealous.” She winked. “And now you don’t have to worry about what people think when you’re here all the time. Everybody knows you’re part of the package.”

I didn’t say I hadn’t realized I was being sold.

Three months earlier, when she’d shown up at my apartment with Ethan in tow and panic in her voice about “the break-in down the hall” and “your arthritis and the stairs,” I’d agreed to stay “for a little while.” The lease on my apartment was month-to-month; my landlord had been planning to sell. It made a certain sense.

“We’ll find you a senior condo or something,” Ethan had said, guilt all over his face. “Temporarily, you can stay with us. It’ll be fun. Like a sitcom.”

I’d rolled my eyes. “Your idea of fun and mine are different,” I’d said. But I’d packed my clothes, my sewing machine, my photo albums. I’d put my old house key on a ring with my new one and told myself this was a bridge, not a cliff.

Now, standing in their guest room in my slip, I felt that key heavy in the pocket of my dress.

The next morning, the doorbell rang at 9:03.

I was at the kitchen table, making Ethan’s old favorite—French toast, maple syrup, strawberries, the way we used to on his birthday. Madison floated in from the hall with that same bright energy.

“Surprise,” she trilled. “We have company.”

The man behind her wore a suit that didn’t quite fit and carried a leather briefcase. “Mrs. Torres?” he asked. “I’m Mr. Lanning. I’m a notary public.”

Alarm bells went off in my spine.

I wiped my hands on a dishtowel. “Notary for what?” I asked calmly.

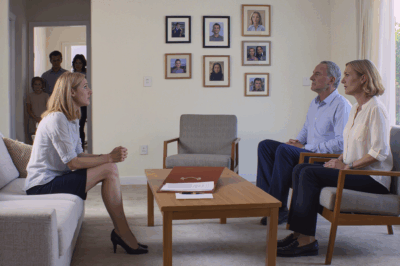

“For some documents,” Madison said. “Nothing scary. Just…grown-up stuff. It’s better if we talk in the living room.”

The living room had been redecorated since I moved in. My old floral couch was gone, replaced by a sleek gray sectional; my bookshelves now housed Madison’s candles and coffee table books about coastal décor.

I sat in Michael’s recliner—Ethan’s recliner now, I suppose. The notary opened his briefcase and pulled out a neat stack of papers, all clipped and tabbed and ready for ink.

“This,” he said, tapping the first, “is a transfer of deed. Ethan and Madison have refinanced the property at 412 Oakview. This document removes your name from the title and consolidates ownership in their names.”

“I see,” I said.

“This,” he tapped the second, “is a residency agreement with Golden Pines Assisted Living. They’ve arranged for you to have a room there. Very nice facility. You’d retain personal property, but management of your finances would move to your son under the existing power of attorney.”

He said it pleasantly, like he was reading me a menu.

My fingers tightened on the armrest. The room felt suddenly very cold.

“Golden Pines,” I repeated. “That’s a nursing home.”

“It’s an assisted living community,” Madison said, perching on the edge of the couch, pink lips pressed into a sympathetic pout. “Everyone there is your age, Mom. Activities, medical staff, no stairs…We’ve already paid your deposit. This just makes everything official.”

“Where is Ethan?” I asked.

“He’s at the gym,” she said. “You know how he is with piles of paperwork. I told him I’d help you with it.”

I looked at the notary. “And you’re comfortable notarizing documents that transfer ownership of a house from a woman who still knows what day it is?” I asked. “Without speaking to my primary physician?”

He blinked. “Mrs. Torres, I was assured you were on board. That this was a formality.”

“Assured by whom?”

He hesitated, glancing at Madison.

“She has been…forgetful,” Madison said quickly. “Leaving the stove on, wandering to the mailbox and forgetting why, getting confused about her medications. Ethan and I just want what’s best for her.”

“That’s quite the diagnosis,” I replied. “Did your medical degree arrive with your wedding registry?”

Color rose in her cheeks. “We’ve been documenting things for months,” she said. “We can’t keep an eye on you while we’re working and raising a baby. Golden Pines is safer. And with the refinance, we can afford a bigger place for the nursery. It’s win-win.”

There’s a kind of rage that’s hot and loud, the kind that makes you shout, throw a plate, slam a door. This wasn’t that. This was cold. Precise. It started somewhere behind my sternum and spread outward in measured heartbeats.

“These documents,” I said, tapping the stack, “assume three things. One, that I am incompetent. Two, that Ethan’s power of attorney is unconditional. And three, that nobody is watching.”

I straightened, feeling every one of my sixty-nine years settle onto my bones like armor.

“Unfortunately for your plan,” I said, “all three are wrong.”

Part 2

Two years before Ethan met Madison, my church friend Irene’s son had taken out a credit card in her name. He’d told her he needed her help “just this once” and that he’d pay it off. When she got the collection notices, she couldn’t afford an attorney. He sold her Honda and moved six states away. She started taking the bus.

I came home from helping her sort through her mail and wrote three things on a yellow sticky note: read, ask, record. I stuck it on my fridge. When Ethan brought me the power of attorney paperwork to sign six months ago—“Just in case something happens, Mom”—I pulled that note down and took it to my kitchen table with a pen.

The attorney Madison had pushed me toward had called the power of attorney “standard.” I’d insisted on taking it home. Then I’d made an appointment with my own attorney, a woman half my age with big glasses and a bigger sense of justice.

“We’re going to add language,” she’d said, pen dancing. “Any use of this POA is contingent upon written certification of incapacity from two licensed physicians, at least one of whom is not your son’s choice.”

I signed that version. We filed it. I slept better.

Standing in my own living room with a notary and my daughter-in-law trying to divest me of my house, I was very glad I had.

“Mr. Lanning,” I said calmly now, “did you read the power of attorney Ethan furnished you?”

He shuffled papers, frowned. “It says your son has authority over financial decisions.”

“Read the second paragraph,” I said.

He did. His eyes widened. “Ah. Conditional upon…two independent physicians’ certification of incapacity. Do you have such certifications, Mrs. Torres?”

“No,” I said. “Because no such incapacity exists.”

I reached into the pocket of my cardigan and pulled out a folded letter. “What I do have,” I added, handing it to him, “is a letter from my primary care doctor, dated last week, stating that I am cognitively intact, oriented, and fully capable of managing my own affairs. Because my daughter-in-law has been telling people otherwise, I thought it wise to ask for documentation.”

He scanned it, cleared his throat, and tugged at his tie. “This…changes things,” he said.

Madison’s mouth tightened. “You’re overreacting, Ruth,” she snapped. “We’re trying to help you. You keep spinning these little conspiracies—”

“You told our neighbor Mrs. Kim that I leave the front door open and wander at night,” I said. “You told my bridge group you were worried I was ‘slipping.’ You told the pharmacist I ‘mess up’ my pills. Those aren’t conspiracies. Those are quotes. I have the dates written down.” I pointed to the spiral notebook now sitting on the coffee table, full of my careful cursive.

I had started that notebook the day I found my pills rearranged in their organizer, sleeping medication moved into the morning slot. At first, I had assumed I’d done it myself. Then it happened again, only on days when Madison had insisted on “helping” with my meds. When I confronted her, she’d laughed.

“You’re imagining things,” she’d said. “It’s cute.”

Irene’s sticky note had burned in my brain. Read. Ask. Record.

So I’d begun to write. Every time she “corrected” my memory. Every time she repeated a story with details that made me sound more helpless than I am. Every tiny act of sabotage. It seemed paranoid at first. Then it became evidence.

“And,” I continued, “you emailed Ethan three weeks ago: We really need to move faster on selling this place. The market’s hot, Mom’s in the way, and I am not changing diapers in a house with floral wallpaper. I told you, Golden Pines is ready whenever we are. I printed it, by the way. Would you like to see it?”

I opened a folder on the coffee table. Inside were copies of the loan note Ethan and I had signed for the down payment, the deed to the house with my name clearly listed as co-owner, and the emails I’d quietly forwarded to myself from the shared family computer when Madison thought teaching me how to use Facebook would mean I didn’t know how to find Sent Mail.

The notary’s Adam’s apple bobbed.

“Mrs. Torres,” he said, voice careful, “given this information, I cannot in good conscience proceed with notarizing these documents.”

Madison rounded on him. “Are you serious?” she hissed. “We made an appointment. We told you what this was.”

“Yes,” he said, snapping his briefcase shut. “And you omitted material facts about your mother-in-law’s capacity and ownership. If you wish to discuss this further, you may do so with your own attorney.”

He looked at me, his gaze apologetic. “I’m very sorry, ma’am,” he said. “Good day.”

When the door closed behind him, Madison’s expression hardened in a way I’d never seen. The sweetness snapped off like brittle candy.

“You think you’re clever,” she spat. “Old people always think writing stuff down makes it real.”

“It does make it real,” I said evenly. “That’s why leases, wills, and loan agreements exist.”

She took a step closer. “You gave us that money,” she said. “You said, ‘Use it, Ethan. Your father would want you to have a home.’”

“I said, ‘This is the last of my savings. We’ll write it as a loan, and you’ll pay me back when you can,’” I replied. “Those words are on that paper. Your signature is under them.”

She swallowed hard. “We can’t pay it back,” she said. “We’re stretched to the limit as it is. The baby, the wedding, Ethan’s student loans…” She waved a hand. “You don’t get it. Your generation had it easy.”

I laughed then. I couldn’t help it. “My generation?” I said. “I worked nights nursing strangers and days folding shirts at Montgomery Ward so your husband could go to college. Your generation expects a house with a three-car garage and a trip to Cabo before the baby arrives.”

Her eyes flashed. “You’re trying to ruin us,” she snarled. “Because you can’t stand that Ethan loves me more than you.”

There it was. The rot behind the perfume.

“You and Ethan’s love are separate accounts,” I said. “One does not overdraw the other. What I cannot stand is theft dressed up as concern.”

Her jaw clenched. “If you don’t sign,” she said, “we’ll just go to court. Ethan has power of attorney. We’ll tell the judge you’re paranoid and combative, that you wander, that you mix up your meds. We have witnesses. My sister can testify.”

“And I,” I said, “will bring my notebook, my doctor’s letter, my loan documents, and the detective from the Elder Abuse unit I spoke to yesterday.”

Her mouth dropped open.

“You went to the police,” she whispered.

“I did,” I said. “Officer Merriman took my statement. Detective Avery called me last night to say they’ve opened a file. Elder financial exploitation is a felony in this state. You might want to google that in between nursery Pinterest boards.”

She stared at me, and for the first time since I’d met her, I saw something that looked like genuine fear.

“You wouldn’t,” she said.

“I already did,” I replied.

For a long moment, the only sound in the room was the ticking of the clock on the mantel. I’d bought that clock with trading stamps the year Ethan started kindergarten. It had measured spelling tests, soccer games, first girlfriends, my husband’s surgery, my own hair growing back after chemo. It ticked, unbothered by all this drama.

Madison recovered quickly, because some people always do.

“You just want attention,” she said, dismissive. “Fine. Keep your half of this crappy house. Enjoy being alone when you fall and break a hip. Ethan and I will be in a gated community with a smart fridge.”

I stood up. My knees popped, old wooden drawers. But I was steady.

“You’re right about one thing,” I said. “I will keep my half of this house. I’ll also keep living in it until I decide otherwise. And when Ethan comes home, he and I will have a conversation. Alone.”

She snorted. “Good luck with that. He’s on my side.”

“Then he can explain to the detective why his name is on a refinance document for a property he doesn’t legally control,” I replied.

I left her in the living room and went to my bedroom, heart pounding like I’d just run laps. I closed the door, leaned against it, and let myself shake for a little while. Anger keeps you upright. Fear reminds you that you’re still human.

My phone buzzed on the nightstand.

Ethan: Sorry, been in meetings all morning. Everything okay?

I stared at the screen. Typed, erased. Tried again.

Me: Madison and a notary tried to get me to sign house over and commit to Golden Pines. I refused. We need to talk. Without her.

Three dots blinked. Stopped. Blinked again.

Ethan: She just texted saying you’re accusing her of stealing. Mom, what is going on?

Me: Come home tonight. Just you. 7 p.m. If you don’t, I’ll assume you’re choosing not to know. But the police will still call either way.

No reply. I set the phone down and made myself a sandwich with shaky hands. You can’t fight on an empty stomach, my grandmother used to say. It applies to every war.

At 6:53 p.m., I heard Ethan’s car in the driveway.

Madison had been gone all afternoon. No note. Good.

Ethan came in through the mudroom, like he always had. For a moment, he was just my boy again, dropping his bag, kicking off his shoes, calling, “Mom?” into the familiar air.

I met him in the kitchen.

“Hey,” he said. He looked tired—dark circles, lines I didn’t remember from last year. “What the hell is going on?”

I gestured to the table, where the folder, the notebook, and the doctor’s letter waited. “Sit,” I said. “We’re going to go through some things.”

He sat. He picked up the loan agreement, frowned.

“I thought that was a gift,” he said.

“I know,” I said. “You’ve said that. Madison’s told everyone that. But that,” I pointed, “is your handwriting at the bottom. ‘Repay as able. With love. – E.’ And there’s my signature. Gift and loan are different words for a reason.”

He swallowed. “She said it was easier for taxes if we treated it as a gift,” he muttered.

“Easier for who?” I asked.

We went through the documents one by one. The deed. The power of attorney with its conditional clause. The doctor’s evaluation. My notebook of dozy sabotage. The email he had written under Madison’s prompting about “moving faster on the Ruth situation.”

By the time we finished, Ethan’s face had gone pale.

“I didn’t know,” he said, voice hoarse. “I mean, I knew she was…pushy. But I thought she was just…worried. About you. About money.”

I looked at my son—the baby I’d rocked through midnight fevers, the teenager I’d watched walk away into dorm life, now a man caught between loyalty and truth.

“Worry doesn’t require lies,” I said. “Or forgery. Or trying to trick someone into signing away their home. Love definitely doesn’t.”

He put his head in his hands.

“God,” he whispered. “What have I done?”

“You married someone who’s very good at getting what she wants,” I said gently. “You trusted her interpretation of reality more than your own eyes. It happens. It doesn’t have to keep happening.”

He looked up, eyes wet. “I told her I never wanted to be like Dad,” he said. “Letting money talk louder than people. And here I am.”

“You’re here,” I said. “You came. That’s a start.”

He scrubbed his face with his palms. “What do you want me to do?” he asked. “Tell me, and I’ll do it.”

It’s a strange kind of power, being asked that.

“First,” I said, “I want you to call Detective Avery tomorrow and tell him what you know. Be honest. Don’t try to soften her actions or your part in them. Second, I want you to go to a different attorney—one she doesn’t know—and ask what our options are. Third, I want you to stop letting her manage your conscience.”

He nodded. “And the house?” he asked.

“The house stays half mine,” I said. “Unless and until I decide to sell. If you want to refinance again in the future, we can talk about it as adults who both own something, not as a child and a caregiver. For now, the papers stay exactly the way they are.”

He exhaled, long and slow, like someone letting air out of a balloon instead of popping it.

“What if she’s pregnant?” he asked suddenly. “She keeps…hinting. Posting baby stuff.”

I thought of the prenatal vitamins I’d seen in the pantry, the pamphlet from an OB-GYN on the counter.

“Then my grandchild will not be homeless,” I said. “But having a child doesn’t erase crimes. It just means we have to be more careful about which patterns we hand down.”

His shoulders slumped. “She’s going to hate me,” he said.

“She already hates anything she can’t control,” I replied. “You changing the script will feel like hate to her. That’s not your fault.”

We sat there for a while, the ticking clock and the humming fridge filling in the gaps.

Finally, he stood.

“I’m going to stay at a hotel tonight,” he said. “I need to…think. Away from her.”

I nodded. “That’s probably wise.”

At the door, he turned. “Mom?”

“Yeah?”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “For not asking more questions. For not…seeing.”

I swallowed. “Thank you,” I said. “That helps.”

After he left, I locked the front door, turned off the lights, and went to bed. I slept badly, dreams full of papers and locked doors and Madison’s voice insisting I remember things that never happened.

In the morning, I woke up with a clarity I hadn’t felt in months. I boiled eggs. I made coffee. Then I picked up the phone and called Detective Avery.

“It’s Ruth Torres,” I said. “I’d like to add an update to my statement.”

Part 3

The officers came on a Tuesday.

By then, my house didn’t feel like mine anymore. It felt like a stage set someone else had designed. My floral curtains still hung in the kitchen, but Madison’s “farmhouse chic” signs—Live Laugh Love, Gather, Blessed—were everywhere. They felt like taunts.

Ethan had moved into a short-term rental near his office. Madison was staying with her sister “for space,” according to her terse text. I stayed put. I wasn’t going to be pushed out of my own home like a lodger.

Detective Avery had been patient on the phone. He’d listened to my story, interrupted only to ask clarifying questions. He’d met me at the precinct, a compact woman with calm brown eyes and a notepad she actually used. She’d told me elder financial exploitation was hard to prove but not impossible.

“You’ve got good documentation,” she’d said, thumbing through copies of my paperwork. “Most people don’t. That helps.”

When she called that Tuesday morning to say they were coming by, I thought she meant just her.

Instead, two patrol cars pulled up behind Madison’s white SUV at 8:17 a.m. The blue and red lights stayed off. Two uniformed officers and Detective Avery walked up the path.

I watched through the lace curtain.

Madison opened the door before they could knock. “Can I help you?” she asked, smile already in place.

“Ms. Cole?” Avery asked. “I’m Detective Avery with the Elder Abuse Unit. We’d like to ask you a few questions.”

Madison laughed, high and brittle. “Is this about Ruth?” she asked. “She’s been…confused, saying the wildest things. I told Ethan we should get her evaluated.”

“That’s exactly what we’re here about,” Avery said. “May we come in?”

I stepped out from the hallway before Madison could answer. “Please do,” I said. “I’ll put on a pot of coffee.”

The officers took seats at the dining table. Avery asked Madison to join them. Madison sat, carefully crossing her ankles like she was filming a commercial.

“We’ve received a report that you and your husband attempted to coerce Ms. Torres into signing away her interest in this property,” Avery said. “Additionally, there are allegations that you’ve misrepresented her medical condition to third parties in order to establish control over her finances.”

Madison’s eyes widened theatrically. “I would never,” she said. “Ruth is…family. We’re trying to help her. She’s been unsafe. Leaving things on the stove, wandering, mixing up her pills. I’ve just been trying to get her the care she needs.”

“Can you provide any documentation of these incidents?” Avery asked. “Dates, times, photos, medical reports?”

Madison faltered. “I…didn’t think to write them down,” she admitted. “We were just…living our lives.”

“That’s all right,” Avery said smoothly. “Ms. Torres did.” She slid my notebook across the table. “Along with this loan documentation, this conditional power of attorney, and this doctor’s letter stating she is currently fully competent.”

Madison’s composure slipped.

“Anyone can get a doctor to say anything,” she snapped. “Old people get paranoid, detectives. You should know that.”

“Maybe,” Avery said. “But usually when they’re paranoid, they don’t also have clear, dated records and legally binding contracts backing up their memory.” She folded her hands. “Ms. Cole, are you aware that in this state, knowingly attempting to deprive an elder of property through fraud or undue influence is a felony?”

Madison’s face drained of color, then flooded with it.

“I want a lawyer,” she said.

“That’s your right,” Avery replied. “You’re not under arrest at this time. We’re just asking questions. But I should tell you that we’ve already spoken to your former employer at Willow Crest Assisted Living. They had concerns about missing funds during your tenure there. And we’re in contact with a Mrs. Ellison whose father alleged you convinced him to sign checks he didn’t understand.”

“That was nothing,” Madison snapped. “Those charges were dropped.”

“Dropped,” Avery agreed, “after he passed away. We’re not here to retry that. We’re here to make sure Ms. Torres is safe now.”

Madison turned to me, eyes blazing.

“You’re doing this to punish me,” she said. “After everything I’ve done. After I opened my home to you, let you live with us—”

“You brought a notary into my living room and tried to get me to sign my house away,” I said. “You went too far.”

For a moment, I thought she might lunge at me. One of the officers shifted his weight, ready.

Instead, she stood abruptly, chair scraping. “I’m not saying another word without an attorney,” she said.

“Then we’re done here for now,” Avery said. “We’ll be in touch through your counsel.”

The officers left their cards and followed her to the door as she grabbed her bag, slammed into the hall, and stalked to her SUV.

“By the way,” Avery called after her, “you might want to check with your husband. We’re meeting with him this afternoon. He’s been very cooperative so far.”

Madison’s shoulders stiffened. She drove away fast enough to spray gravel.

I sank into a chair when they’d gone.

“Is this really happening?” I asked Avery.

“It is,” she said. “It’s going to be slow. The DA’s office is cautious with these cases. But you’ve done everything right, Ms. Torres. You gave us a fighting chance.”

“You’ll call me Ruth if you’re going to keep insulting me by telling me I did everything right,” I said, half joking.

She smiled. “Deal, Ruth.”

Over the next few months, life turned into a series of appointments and letters. Ethan met with a separate lawyer, filed his own statement. It was agonizing watching him peel back each layer of Madison’s behavior and realize how much had been a lie. There were days he’d call and just breathe on the line, like words were too heavy.

“I keep thinking about all the times she ‘forgot’ to give you messages,” he said once. “Or when she told me you were tired and I didn’t need to come over. God, Mom. I let her convince me you didn’t want me there.”

“Shame’s favorite trick is isolation,” I said. “You’re not special.”

One afternoon, Patricia—Madison’s mother—showed up on my porch. She wore a wool coat despite the mild weather and carried a tin of cookies.

“May I come in?” she asked.

I hesitated, then stepped aside.

She sat at my kitchen table, fingers twisting a paper napkin into frayed rope.

“I don’t know how to say this,” she began. “I’m so sorry.”

“You’re not the one who tried to steal my house,” I said.

“No,” she admitted. “But I raised the one who did. That…counts.”

She took a breath. “When Madison was nineteen, she ‘borrowed’ her grandmother’s credit card,” she said. “Ran up three thousand dollars in a month. We paid it off. Told ourselves it was a phase.” She shook her head. “When she was twenty-five, there was…another situation. A boss who let her ‘manage petty cash.’ Money went missing. Charges were filed. We got her a lawyer. He said she needed therapy, not prison. The judge agreed. We told ourselves she’d learned her lesson.” She laughed bitterly. “We were so desperate to believe she wasn’t that kind of person that we ignored all the ways she kept being that kind of person.”

“They always said you were the soft parent,” I murmured.

“Soft in the spine,” she said. “Hard in the head when it came to everyone else. We held everyone to standards we didn’t hold her to. Now look.”

She slid an envelope across the table.

“I can’t fix what she’s done,” she said. “But I can fix one part. That’s a cashier’s check. For twenty thousand. Your down payment, plus some.” Her eyes filled. “Please. Take it. If the court orders restitution, you can rip it up. For now, I need to know I did one right thing.”

I stared at the envelope. The exact number I’d drained from my savings written in neat black ink, plus a little more.

“I’ll accept it,” I said. “On one condition.”

She blinked. “Name it.”

“You stop telling yourself you failed because your daughter did wrong,” I said. “You didn’t put her hands on my paperwork. You just…looked away too often.”

Her mouth trembled. “That’s still on me.”

“Yes,” I said. “And no. It’s complicated. We’re complicated. That doesn’t make you the villain in my story.”

She let out a breath she’d been holding for, I suspect, years.

“Thank you,” she whispered.

A month later, the DA filed charges. Attempted theft from an elder, fraud, abuse of a vulnerable adult. When the news reached Madison, she called Ethan six times in a row. He didn’t answer. She texted me once: You’re disgusting. You’re doing this to your own grandchild.

I didn’t reply. That accusation only works if you believe silence is worse than continuing to hand someone the knife they keep nicking you with.

The day of the arraignment, the courthouse hallway was full of people whose lives had reached one of those awful pivot points. Some clutched folders. Some clutched hands. Madison walked in wearing beige slacks and a white blouse, hair smoothed into a low ponytail. She looked smaller without heels and a phone in her hand.

Her attorney pleaded not guilty for her. The judge set conditions for bail. We left. It felt anticlimactic.

“Justice is a crockpot, not a microwave,” Avery said wryly. “Takes time.”

Time passed. Leaves turned, Emma was born, Ethan’s divorce proceedings began. In between diaper changes and burp cloths, he testified about emails and documents and conversations he’d once dismissed as “just Madison being…Madison.”

It hurt. Everyone.

Not as much as it would have hurt to let it go.

Part 4

The day of the sentencing, I wore my navy dress again.

It fit a little looser. Grief is a strange diet.

The courtroom was half-empty. Elder financial abuse cases don’t draw crowds like murder trials do. There were no cameras, no reporters, just a scattering of relatives and a row of law students in the back observing for class.

Madison sat at the defense table, hands folded. Her lawyer had coached her into an expression of sober regret. If I hadn’t watched her stage every other emotion for three years, I might have believed it.

The judge—a woman in her fifties with gray streaking her dark hair and patience worn thin—read the charges. Attempted theft by deception. Abuse of a vulnerable adult. Fraudulent use of power of attorney.

“You have pleaded guilty to these charges as part of a negotiated plea,” the judge said. “Before I accept that plea, I’m going to say a few things, Ms. Cole.”

Madison lifted her chin slightly.

“I see a lot of terrible things in this courtroom,” the judge said. “Violence, cruelty, greed. But there is something especially ugly about exploiting the trust that exists within a family.” She glanced at me, then back at Madison. “You did not target a stranger. You targeted your husband’s mother. You used the language of concern to disguise a plan to enrich yourself at her expense. That is not a lapse in judgment. That is a pattern.”

Madison’s jaw tightened.

“I have read the letters submitted on your behalf,” the judge went on. “I see that you are a mother yourself. I would like you to imagine—actually imagine—someone doing to your child at nineteen what you did to Ms. Torres at sixty-nine. I doubt you would call it a misunderstanding.”

She paused.

“I am accepting the plea,” she said. “You will serve twelve months in state custody, followed by three years of supervised probation. You will pay restitution to Ms. Torres in full. You will attend mandatory financial ethics counseling. And you will have no unsupervised contact with any elder in a fiduciary capacity during your probation.”

The gavel came down. Wood on wood. Two pieces of dead tree making a sound that, somewhat inexplicably, carried a sense of closure.

Afterwards, in the hallway, Avery hugged me.

“You did it,” she said.

“No,” I said. “We did.”

She smiled. “That’s the nicest ‘don’t make me the hero’ I’ve ever gotten.”

Ethan joined us, Emma on his hip, Patricia hovering nearby.

“I’m sorry she’s your mother,” I said softly to Emma, brushing her tiny hand.

“I’m sorry she’s your ex-wife,” I said to Ethan.

“Me too,” he said. His eyes were tired but clearer than they’d been in a long time.

“Do you regret it?” I asked. “Calling the detective, testifying?”

He took a breath, looking down at Emma’s dark fuzz of hair.

“I regret not seeing sooner,” he said. “I don’t regret stopping it.”

On the drive home, Emma gurgled from her car seat. We stopped for ice cream, because why not.

We rebuilt.

Not in a montage, not tidily. Slowly. Sloppily. There were still nights when Ethan would text at midnight: you awake? and I’d call and listen to him say, “I dreamt she was in the house again.” There were days I’d check the lock twice on the front door, as if Madison might show up with a new notary and a better plan.

But most days were ordinary in the best way.

I taught Emma to stir brownie batter without grabbing the spoon too high. I taught her the names of the birds at the feeder. I taught Ethan how to cook something more elaborate than scrambled eggs and toast.

“Dad always did the grilling,” he said one night, staring at the pan. “I feel like I missed some…gene.”

“You didn’t,” I said. “You just outsourced it. Like other things.”

We joined a support group for families affected by financial exploitation. In a church basement on Thursday nights, we sat in a circle with people whose kids had drained their accounts, whose brothers had used joint credit cards to fund gambling, whose nieces had “borrowed” and never paid back.

It was both comforting and horrifying.

One woman, a retired teacher, told us her granddaughter had sold all her jewelry while she was in the hospital. “She left me the empty boxes,” the woman said. “Like I wouldn’t notice.”

We nodded. We all knew that particular brand of insult.

At the end of each meeting, we went around and shared “one thing I did this week that protected me.” I sometimes said, “I read a contract.” Sometimes, “I told my son no when he asked me for my password so he could ‘fix’ something.”

Sometimes, the thing I did to protect myself was simple: I allowed myself to enjoy a day without thinking about courtrooms.

I started volunteering at the library, running a “Know Your Rights” workshop for older adults. We covered basics like how to read loan agreements, what a power of attorney really means, how to say, “I’m going to have my lawyer look at this” even if you don’t have one yet.

“Pretend you do,” I told them, and they laughed. “Sometimes a bluff buys you time.”

One afternoon, a man in his seventies stayed after everyone else had left. “My son says I should add him to my bank account ‘for convenience,’” he said. “What do you think?”

“I think you should ask yourself if you trust your son more than you fear convenience,” I said gently. “And maybe talk to someone whose job it is to look out for you. Not just for him.”

He nodded, eyes wet. “Thank you,” he said. “I thought I was being selfish.”

“You’re not being selfish,” I said. “You’re being a good steward. Of yourself.”

Madison got out of prison. She went to her mother’s house. She petitioned for supervised visitation with Emma. The court agreed, with conditions. A social worker sat in Patricia’s living room while Madison held Emma for the first time in a year.

I didn’t go. Ethan asked if I wanted to be there. I said no.

“I don’t want Emma to associate that house with all of us staring at her like a symbol of something,” I said. “She’s a baby, not a peace treaty.”

He laughed, a genuine sound. “You always know how to make it about the real thing,” he said.

Things got…less raw with time. Madison took her counseling seriously. Or she pretended to, which, frankly, was good enough if it made her behavior less dangerous. She got a job that did not involve managing anyone’s money. She sent Ethan emails about child support payments that were surprisingly businesslike. Sometimes, when I picked up Emma from Patricia’s house, I saw Madison’s car in the driveway and my pulse sped up. But our paths rarely crossed.

Once, we did.

It was at the grocery store. I was in the produce section, picking out tomatoes, when I heard her voice at the end of the aisle.

I almost walked away. Then I thought, Why should I?

I finished choosing my tomatoes and turned. She pushed a cart slowly, alone. No makeup this time. No phone in hand.

We locked eyes.

“Hi,” she said stiffly.

“Hello,” I replied.

Silence, thick as jam.

“Emma loves your cookies,” she blurted. “She…talks about you all the time.”

“I’m glad,” I said.

She swallowed. “I’m…trying,” she said, and the words sounded dragged out of her. “I know you probably think it’s useless. But I am.”

I looked at her—the woman who’d tried to uproot my life, who’d lied, who’d also given birth to my granddaughter.

“I think,” I said, “that trying matters. I also think consequences matter. Both can be true.”

She nodded, eyes bright. “I know you don’t owe me…anything,” she said. “I just wanted to say that. That I’m…trying not to be that person anymore.”

I considered, then said the truest thing I could that didn’t involve giving her absolution she hadn’t earned.

“For Emma’s sake,” I said, “I hope you succeed.”

She nodded again. “Me too,” she whispered.

We moved on. She went one way, I the other. The tomatoes were red and heavy in my cart. I felt oddly lighter.

Part 5

A year after Madison’s sentencing, Emma turned three.

We threw her a party at the park—just a few kids from her daycare, some of Ethan’s coworkers’ children, Patricia, me. No clowns. Lots of bubbles.

Emma had inherited her father’s cautiousness and her mother’s charm. She insisted on introducing me to each of her friends.

“This my Gamma,” she said, patting my leg. “She make cookies.”

High praise.

As the kids tackled a piñata shaped like a unicorn, one of the other mothers glanced at Ethan, then at me.

“She talks about you all the time,” she said. “Gamma this, Gamma that. You’re lucky.”

“I am,” I said. “Very.”

“Her mom’s…not in the picture?” she asked carefully.

“She’s in a different kind of picture,” I said. “We’re working on cropping and lighting.”

The woman laughed, not fully understanding, but that was fine. Not everyone needs the whole story.

Later that evening, after we’d vacuumed cake crumbs out of the couch and put away the streamers, Ethan and I sat on his porch, watching dusk turn the neighborhood blue.

“Do you ever miss her?” he asked suddenly.

“Who?” I said, though I knew.

“Madison,” he said.

I thought about it.

“I miss the person I thought she was,” I said. “The one who made you laugh in the kitchen. The one who researched baby carriers for hours. That person wasn’t entirely fake. She just…shared space with someone who could also do very cruel things.”

He nodded. “I feel guilty that I still love parts of her,” he admitted. “Like that means I’m betraying you. Or myself.”

“Love doesn’t cancel truth,” I said. “Or vice versa. Feelings are messy. That doesn’t make them wrong. It’s what you do with them that matters.”

He exhaled. “You should write a book,” he said.

“About what?” I snorted. “Power of attorney clauses?”

He grinned. “I’d read it.”

We fell into a comfortable quiet.

“I don’t think I ever thanked you,” he said after a while. “Not just for…stopping her. But for…not letting me drown in pity afterward. For making me call the detective. For not letting me hide behind ‘we didn’t mean it.’”

“You’re welcome,” I said. “Accountability is the rent you pay for getting to grow up.”

He laughed. “Put that in your book.”

I went home that night to my own house. Mine, legally and practically. Oakview had become a different place with Madison gone—a place where my floral curtains belonged again, where my cross-stitch samplers made sense next to Ethan’s framed college diploma and Emma’s finger paintings.

I still got mail from Golden Pines sometimes. Brochures promising bingo nights and “independent living with support.” I recycled them. I knew plenty of people happy in places like that; I wasn’t opposed on principle. I was opposed to being shoved there for someone else’s convenience.

At the library workshop the next month, a woman in her early seventies raised her hand.

“My daughter wants me to move in with her,” she said. “Says she can ‘take better care’ of me than I can. But I like my condo. I like my neighbors. Am I being selfish if I say no?”

I thought of Madison at my door with a notary and a smile. Of the fear threading under my anger. Of the way it felt to stand my ground.

“No,” I said. “You’re not selfish. You’re clear. There’s a difference.”

She nodded slowly. “So what do I say?”

“You say, ‘I love you,’” I said. “And then you say, ‘I’m staying where I am until I decide otherwise.’ And if they push, you say, ‘We can talk to a lawyer together so everyone feels comfortable.’ If they refuse that, then you have your answer about their motives.”

After class, she came up and squeezed my hands.

“Thank you,” she said. “I needed someone to tell me I wasn’t losing my mind.”

“You’re not,” I said. “You’re just finally listening to it.”

Sometimes, late at night, I sit at my kitchen table with a cup of herbal tea and my grandfather’s watch. I wind it, even though I don’t have to. I like the feel of the mechanism catching, gears engaging, time lined up and ready to go.

That watch has seen a lot tucked next to my pulse: my wedding vows, Ethan’s birth, Mike’s funeral, chemo drips, my first day back at work, Ethan’s college graduation, countless dinners cooked on stoves I remembered to turn off. It sat in my pocket the day Madison tried to get me to sign away my house. It ticked away in the silence after the door closed.

It reminds me of this: time does not stop for betrayal. It does not pause for court dates. It keeps moving. What you do with it is up to you.

After the wedding, my daughter-in-law showed up at my door with a notary and a plan: sell the house from under me, ship me off to an institution, turn my lifetime of work into her starter equity.

She thought age made me weak. She thought being a mother made me pliable. She thought paperwork was her weapon alone.

What she didn’t count on was that a woman who has spent her life reading the fine print, loving a son, and surviving this world might have more leverage than she looks.

I didn’t sign. I went to the police. I told the truth. I let the justice system do its slow, imperfect work. I held my ground.

And now?

Now, there’s a little girl who climbs onto my lap, curls damp from the bath, and says, “Gamma, tell story.” Sometimes I tell her about dragons and knights. Sometimes I tell her about a woman who almost lost her house and found her voice instead.

Always, I end with the same line:

“And she lived exactly where she wanted. For as long as she wanted. And she helped other people do the same.”

Emma always claps.

“Again,” she demands.

So I do. In one form or another, for her and for myself and for anyone who has ever sat in their own living room feeling the walls close in around them and thought, This can’t be how it ends.

It isn’t.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My DAD Shouted “Don’t Pretend You Matter To Us, Get Lost From Here” — I Said Just Three Words…

My DAD Shouted “Don’t Pretend You Matter To Us, Get Lost From Here” — I Said Just Three Words… …

HOA “Cops” Kept Running Over My Ranch Mailbox—So I Installed One They Never Saw Coming!

HOA “Cops” Kept Running Over My Ranch Mailbox—So I Installed One They Never Saw Coming! Part 1 On my…

I Went to Visit My Mom, but When I Saw My Fiancé’s Truck at Her Gate, and Heard What He Said Inside…

I Went to Visit My Mom, but When I Saw My Fiancé’s Truck at Her Gate, and Heard What He…

While I Was in a Coma, My Husband Whispered What He Really Thought of Me — But I Heard Every Word…

While I Was in a Coma, My Husband Whispered What He Really Thought of Me — But I Heard Every…

Shock! My Parents Called Me Over Just to Say Their Will Leaves Everything to My Siblings, Not Me!

Shock! My Parents Called Me Over Just to Say Their Will Leaves Everything to My Siblings, Not Me! Part…

At Sister’s Wedding Dad Dragged Me By Neck For Refusing To Hand Her My Savings Said Dogs Don’t Marry

At Sister’s Wedding Dad Dragged Me By Neck For Refusing To Hand Her My Savings Said Dogs Don’t Marry …

End of content

No more pages to load