After the Accident, I Couldn’t Walk—My Husband Left Me for Another Woman. But the Way I Came Back…

Part One

“I don’t want you climbing anymore,” David said one morning, as if he were asking for more coffee. I froze halfway through lacing my boots, one hand on my harness, the other closing around the tongue of a shoe.

“You’re not twenty-five,” he went on, folding his tie as though straight lines could make a crooked thing true. “It’s time to think about kids.”

His voice wasn’t angry. It was worse—calm, patronizing, the gentle cadence he used when passing along something he’d heard from Elaine. His mother planted seeds; David provided a watering can.

It was supposed to be a good day. We had bought tickets to Nepal for the fall—three blue pins on our map had been circled, then circled again in anxious ink. I was scheduled to lead a kids’ group at the climbing center that afternoon; in the evening we were going to a little Thai place with more plants than tables to celebrate five years married. I’d dyed my hair copper the day before, bold and bright, like a flare fired skyward just for me.

“You liked this color yesterday,” I said, keeping my voice level.

“I still do,” he murmured, threading silver cuff links into his shirt. “But maybe it’s time we grew up a little.”

I laughed it off, kissed his cheek, grabbed my gear, and let the words follow me out the door like a shadow.

Climbing was the first language I learned that didn’t require words. As a child, I was kinetic—knees full of gravel, elbows of chalk, the girl who could not sit when told to be still. The first time I clipped into a harness at ten, the world arranged itself for me: holds became a sentence, and I could read it with the soles of my feet. At thirty-two, I had turned that sentence into a life—weekend classes for kids with shoelaces untied, team-building for accountants who learned to trust their feet, a safety system I helped design that earned national certification. I wasn’t just passionate. I was good.

Our apartment in Portland reflected that life—sunlight through big windows, trekking boots in the hall, a map above the bed with red pins where we’d been and blue where we dreamed to go. Nepal had three blues. I had circled them with a pen until the paper thinned.

That Saturday I was elbow-deep in masoor dal—the kitchen smelling of toasted cumin and too much ginger—when the doorbell rang.

“Can you get that?” I called over my shoulder.

I turned with a wooden spoon in my hand and saw, framed in our doorway, our friend Rachel—and behind her, in a beige suit and judgment, Elaine.

“I was in the area,” she said briskly, stepping in as though we’d asked. “Thought I’d drop by.”

Rachel gave me a tight, sorry smile. “I didn’t know she was coming.”

“It’s fine,” I said, though a small knot tied itself under my breastbone.

Over lunch, Elaine delivered criticism wrapped in concern like a passive-aggressive gift basket. My cooking? Too spicy. My career? Not a real job. “When will you have real responsibilities?” she asked, dabbing the corner of her mouth with a napkin. When I mentioned our Nepal trip, she pursed her lips as if tasting something off.

“You’re not getting any younger, Julia,” she said (when she bothered to use my name, she often sharpened it). “It’s time to think about a family.”

“We have a plan,” I said, keeping my tone even. “Nepal in the fall. Maybe kids next year.”

She shot David a look—the kind that carries an instruction manual in its gaze. He shifted in his chair. He did not defend me.

“You’ve got too many mountains on your list and not enough sense of time,” she muttered, slicing naan like it had wronged her.

That night I sat with David on the couch, knees touching, TV glowing. “She doesn’t think I’ll ever give you children,” I said.

“She’s from another time,” he answered, sighing. “For her, a woman’s worth is domestic.”

“You don’t believe that, right?”

“Of course not,” he said, kissing the top of my head.

But even then, I didn’t know if he said it for me or to hear himself say the kind thing he wished were true.

Two days later, in the gym’s cool, chalk-dusted air, I clipped a nervous new father into a top rope. He was stiff, out of shape, trying and ashamed of it.

“You’ll be fine,” I said. “Most of climbing is trusting the rope.”

The class warmed, laughter echoing off high ceilings, music playing low. “Coach Julia, watch this!” a girl near the top called.

The sound came first—a small, sharp zip, as if a seam were tearing. The rope didn’t snap, not fully, but enough. The man on belay lost his footing. The fall was a story told in frames: his body twisting, the rope skidding over a biner, someone gasping, my own feet moving.

I lunged, grabbed the rope, anchored my weight. Two hundred and forty pounds hit my body like a freight train. The floor rose. The world blinked out.

When I woke, the ceiling above me was too white, the lights too bright, the smell too clean. Pain had moved in, not sharp but hollow, like something essential had been scooped out of me. A warm hand wrapped mine.

“Julia,” a voice said, low and shaking. “You’re awake. Thank God, you’re awake.”

David’s face swam into view—paleface, red eyes. I tried to speak. My throat burned. He lifted my head and held a straw to my lips.

“You took the fall,” he said when I could manage a whisper. “A student lost his grip. You saved him. But you… you didn’t land well.” He hesitated, swallowed hard. “Spinal injury. T8 and T9. They’re saying… mobility may be compromised.”

“Compromised,” my brain repeated, slow, uncomprehending, as if trying to find purchase on syllables. Like what—weeks on crutches? A cane?

A doctor came with X-rays that looked like fog and words that tasted like iron. Paralysis hung in the air like a storm cloud. Permanent. Maybe. They weren’t sure. They’re never sure. They said too early to tell, depends on your body. The truth was in their eyes.

Elaine visited the next day wearing pearls and the faint satisfaction of someone who predicted the weather then enjoyed the rain. She brought a basket of oranges and lifestyle magazines. “I told you that climbing nonsense would end in disaster,” she said quietly to David, when she thought I was asleep. She looked at me the way people look at closed stores. “And now she won’t just not give you children. She’ll need to be cared for like one.”

David said nothing. His jaw tightened. His eyes went somewhere the room couldn’t follow.

The hospital room shrank into a world measured in beeps and injections, plastic cups and the slow leak of days. I became a patient, a diagnosis, a chart that made nurses nod and men in coats sigh. Not a climber. Not a coach. A body, technically alive, lying still.

David visited every day. He brought me books and playlists like offerings to an altar. He reported what the world was doing without me. He tried to smile. It looked like work. I watched something in him dim. It wasn’t his fault. He hadn’t asked for this. Neither had I. But the fact remained standing between us like a wall.

They brought me home on a Wednesday. Our bright little apartment, once a landscape of boots and curry and laughter, had been transformed. The queen bed gone, replaced by a hospital bed with rails. A commode chair in the corner. A lift device parked by the window. The carpet ripped for easier wheel travel. The home we had made became a clinic.

The first night, David tried cheer. “We’ll get you back on your feet,” he said. “It’s a middle chapter.”

I nodded. The catheter tugged. The bag on the bed smelled faintly of lemon disinfectant. No middle chapter had ever felt more like an ending.

He learned to adjust tubes and inject meds. He googled bedsores and passive range-of-motion exercises at three in the morning. He wanted to help. He did. And with each day, he broke a little—around the eyes, in the voice. He stayed in his office longer. Sometimes I would see him sitting in the dark with his old drafting table glowing from the streetlight like a ghost of competence.

Elaine came often. She stroked his arm and said, “You’re so strong to do this for her,” as if I weren’t in the room. She had brochures for facilities that smelled like the same lemon disinfectant and called them “professional environments.” “You wouldn’t want him to burn out,” she said to me, and smiled. “Would you?”

At night, through painkillers and their soft-cloud hallucinations, I heard voices on the balcony. David whispering. Rachel murmuring. “When I’m with you, I can breathe,” he said once. I rolled back and closed my eyes so hard stars appeared under my lids.

The next morning, he brought burnt French toast—the way I liked it because my father had always burned it. I looked at the tray and then at him.

“You should tell me,” I said.

“Tell you what?” He feigned an ignorance beneath which sat pleading.

“That you want out. That I am too much.”

He sat on the bed’s edge, rubbed his face. “I don’t know how to say it,” he whispered. “I feel like I’m drowning.”

“Me, too.” My voice didn’t tremble. Perhaps I had run out of tremble.

He proposed Clearbrook Manor like a man proposing a pragmatic solution in a meeting. “Temporary,” he promised. “Until you’re stronger.”

“I’m not getting stronger,” I said.

He looked away. He said, “Let’s talk later.” But later had already arrived and put its bag down.

We packed a bag—shirts that still smelled faintly of chalk and wind; a photo of us at the top of Mount Hood—cheeks red, eyes alive; my hair in a braid, his arm around me. Rachel stopped by with tulips that would look nice by any window. She didn’t say, I’ll take care of him. She didn’t have to.

The ambulance took me at noon. Clearbrook’s lobby was beige and efficient. The walls of my room were yellowed. A crack in the ceiling shaped like a split heart gaped above me. The nurse, Valerie, had kind eyes and distracted hands. “You’ll settle in,” she said. I smiled because that was my part.

Days were a blur of measured pills, flickering lights, the shuffle of slippers in the hall. The food tasted like nothing and yet left a flavor you couldn’t name. David called at first—brief, obligation trimmed with love. “How are they treating you? Have you been outside?” He promised weekend visits that broke when they tried to land. “Work is insane,” he said. “Next week.” Next week never arrived.

A rash bloomed red and angry on my forearms. “Laundry soap,” Valerie said, handing me a cream that burned. It spread to my neck, my back. Sheets scratched. Nights were made of itch.

Part Two

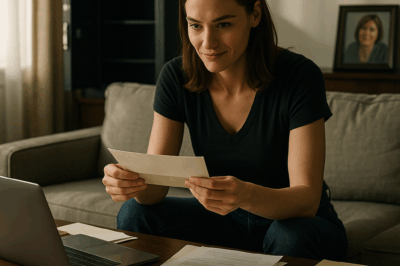

I took out the Mount Hood photo. We grinned in the picture like the world had leaned in to take our side. Now, that girl felt like a fable. I didn’t cry anymore. I practiced existing in the space where the ceiling met the walls and breathed lemon air.

Then a new doctor appeared—soft steps, worn leather notebook, wire-rim glasses, a presence that did not try to fill the room just because he had a title.

“Julia Carter?” he asked, glancing at the chart. “I’m Dr. Ethan Blake. Neurorehab.” He looked at me, not past me. “I reviewed your file.” He paused, then added, “I think there’s more we can try.”

“More what?” I asked, wary of hope. Hope was a cliff. I did not have a rope.

“Rehabilitation,” he said. “Advanced methods. Not miracles. Effort.” He examined my legs, tapped reflex hammers, watched my face for flinches. “Your injury notes suggest partial compression, not full severance. You have deep tissue response. It’s quiet. But not gone.”

Everyone says maybe. He said, still.

He asked if I’d be open to unofficial sessions. “The staff’s limited,” he said. “I’ve worked at facilities that aren’t.” He smiled, a little crooked. “I can do better than what you’ve been given.”

“Yes,” I said, before logic could build a rationale around my fear.

He didn’t talk to me like I was a broken appliance. He came every afternoon after rounds, rolled up his sleeves, and greeted me as if we were resuming an interesting conversation. He learned my food cravings like a friend—fresh raspberries, buttery toast—and smuggled in a pint of the good yogurt when the kitchen sent me gray pudding. He played me R.E.M. and Sia and Simon & Garfunkel because he remembered I said Sweet Disposition made me think of unpaved trails and air that tasted green.

He showed me exercises that looked like nothing. Toe curls. Breath pacing. Visualizing movement as if your body could be tricked into remembering itself. “Neuroplasticity isn’t magic,” he said. “But it is stubborn. Like you.”

He brought in a therapist from another clinic—Marta, quiet and precise, with resistance bands in a bag and 80s playlists on her phone. We laughed in a way that didn’t feel like an apology. When nothing changed, they didn’t make me feel like nothing had. When a tingle fluttered in my right foot, Valerie called it phantom. Ethan checked it, smiled, and said, “Not a ghost.” I believed him more than I believed the lemon air.

We didn’t tell anyone about the flutter at first. We kept it like a candle you cup your hands around to protect from draft. We made a habit of trying. Slowly, I became a person who tried again.

In those afternoons, we became something else—friends. He told me about Lily, five, a girl who wore an astronaut helmet to breakfast because she needed the extra oxygen of dreaming big. He showed me a picture of her in a sparkly suit, grinning so hard the photo looked like it had light of its own. He said he wasn’t married anymore, and his voice gentled around the admission. I didn’t ask for details. I told him about David—enough to be honest, not enough to scrape the scab. He didn’t pity. He didn’t push. He listened.

One day I flexed my toes. Barely. For a second. Marta breathed in like someone seeing fireworks at noon. Ethan grinned. I cried, because it was real, because I was.

He gave me a navy journal. “Write everything,” he said. “Not polite. True.”

So I did. I wrote about rage—not just at David, but at lemon air and flickering lights and the word compromised and nurses who said honey but not I hear you. I wrote about loss—the girl on the cliff and the adulterated version of me who had agreed to be patient like a virtue instead of a weapon used against her. I wrote that losing David hurt less than realizing I had let my life be small enough for his contempt to sit comfortably inside.

Three days later, the last page of the journal—the letter I’d never intended to send—appeared on my bedside tray, printed and folded. Valerie hovered, guilty. “Found it changing linens,” she said. “Thought maybe it should… be read.”

I showed Ethan. He read, jaw tight, then said, “It’s good. And it’s yours.”

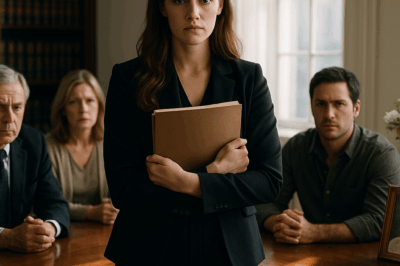

Two weeks later, David knocked on my door holding tulips and a face that had learned what mirrors were for.

“I read it,” he said. He sat, careful not to jostle the bed as if grief were a patient too. “I was a coward. Rachel was a mistake. All of it was a mistake.”

“Why are you here?” I asked.

“Because I miss you,” he said. “Because I hate who I’ve been. Because your letter made me realize I didn’t lose you the day of the accident. I lost you the day I stopped trying.”

“Do you want to fix this?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “If you’ll let me.”

“I’m not the woman you left,” I said. “I won’t be her again.”

“I know.”

“Then don’t ask me to come back. Don’t ask for before. It’s gone.”

He looked at the sink, at his hands, at the tulips he’d brought that would die in lemon air. “What do I do?” he asked finally.

“You start here,” I said, and handed him the journal. “You read. Then you figure out who you are without me. Then maybe you build something that belongs to the man you’re learning to be.”

He held the journal like it might catch fire. He nodded. He left. He did not ask for a timeline for his redemption. I was grateful.

The first time I stood was not a movie. No swelling violins. No staff gathered in the doorway clapping. Just a quiet afternoon. Marta at my elbow with a gait belt. Ethan crouched, watching tendons like a weather system.

“Whenever you’re ready,” she said.

I closed my eyes, drew air in until I felt its weight, pressed my heels down into a floor that had become more myth than friend, and pushed. My right knee snapped into a lock and trembled. My hands clamped white to parallel bars. My core screamed. I stood for five seconds. Then I sat.

I laughed in a way that echoed in the hall and made someone peer in with a frown. I didn’t explain.

By spring I shuffled with a walker from bed to window. By summer I crossed the garden with a cane. The day I left Clearbrook, I signed papers with a hand steady enough to put Julia where they expected patient. Valerie muttered that she hadn’t thought I’d make it. I smiled because I had learned I didn’t need her to think anything about me.

Ethan drove me to a second-story walk-up with scuffed stairs and light pooling on the floor like blessing water.

“This is mine,” I said as he carried a box labeled BRUSHES into a space that smelled like possibility and dust. “I signed the lease last week.”

“No elevator?” he asked.

“Always stubborn,” I said. We grinned like people who have earned the right to use that word kindly.

He paused at the door. “If you ever want—”

“I’ll call,” I said. He nodded. He didn’t make it about him.

I slept the first night without machines. In the morning, I stood—slow, trembling, fierce— and opened the blinds to let the light in. It was ordinary. It was everything.

I didn’t plan to see David again. But life loves closure almost as much as it loves open doors. I was at the community center for a wellness talk Ethan had recommended when I wandered into the café across the street afterward. I stood in line behind a man who asked too many questions about milk alternatives and then turned with my coffee and saw him. He looked older, thinner. Grayer at the temples. He saw me and his face arranged into astonishment.

“You look incredible,” he said.

“I feel incredible,” I replied.

He glanced at the cane, then at my face. He started to speak. Stopped. “I’ve been following your progress,” he said. “Ethan mentioned… I’m not the hero in your story.”

“You were once,” I said. “Not at the end.”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I know it doesn’t fix anything. I think about it every day.”

“I forgave you,” I said. “Not for you. For me.”

He exhaled like a man who had been holding his breath under water. I reached into my bag and handed him a photo. Me at Angel’s Landing: cane in one hand held aloft like a banner, the canyon behind me spilling gold.

“It’s real,” I said. “Every part.”

“You did it,” he whispered.

“No,” I said, stepping back toward the door. “I’m doing it.”

Outside, the sun poured down the street like music. I walked into it, cane steady in my hand, nothing behind me I needed to stare at to prove I had left.

I had not gotten back what I lost. I had built something new on ground I used to believe only belonged to other people. And that’s the story I keep telling when anyone asks me how I came back: I didn’t. I went forward.

END!

News

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside. ch2

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside Part…

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… ch2

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… Part One…

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… ch2

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… Part One…

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… ch2

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… Part One…

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back. ch2

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back Part One The morning sunlight poured through…

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door. ch2

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load