After the Accident, I Couldn’t Walk—My Husband Left Me for Another Woman. But the Way I Came Back…

Part One

“I don’t want you climbing anymore,” David said one morning, as if he were asking for more coffee. I froze halfway through lacing my boots, one hand on my harness, the other closing around the tongue of a shoe.

“You’re not twenty-five,” he went on, folding his tie as though straight lines could make a crooked thing true. “It’s time to think about kids.”

His voice wasn’t angry. It was worse—calm, patronizing, the gentle cadence he used when passing along something he’d heard from Elaine. His mother planted seeds; David provided a watering can.

It was supposed to be a good day. We had bought tickets to Nepal for the fall—three blue pins on our map had been circled, then circled again in anxious ink. I was scheduled to lead a kids’ group at the climbing center that afternoon; in the evening we were going to a little Thai place with more plants than tables to celebrate five years married. I’d dyed my hair copper the day before, bold and bright, like a flare fired skyward just for me.

“You liked this color yesterday,” I said, keeping my voice level.

“I still do,” he murmured, threading silver cuff links into his shirt. “But maybe it’s time we grew up a little.”

I laughed it off, kissed his cheek, grabbed my gear, and let the words follow me out the door like a shadow.

Climbing was the first language I learned that didn’t require words. As a child, I was kinetic—knees full of gravel, elbows of chalk, the girl who could not sit when told to be still. The first time I clipped into a harness at ten, the world arranged itself for me: holds became a sentence, and I could read it with the soles of my feet. At thirty-two, I had turned that sentence into a life—weekend classes for kids with shoelaces untied, team-building for accountants who learned to trust their feet, a safety system I helped design that earned national certification. I wasn’t just passionate. I was good.

Our apartment in Portland reflected that life—sunlight through big windows, trekking boots in the hall, a map above the bed with red pins where we’d been and blue where we dreamed to go. Nepal had three blues. I had circled them with a pen until the paper thinned.

That Saturday I was elbow-deep in masoor dal—the kitchen smelling of toasted cumin and too much ginger—when the doorbell rang.

“Can you get that?” I called over my shoulder.

I turned with a wooden spoon in my hand and saw, framed in our doorway, our friend Rachel—and behind her, in a beige suit and judgment, Elaine.

“I was in the area,” she said briskly, stepping in as though we’d asked. “Thought I’d drop by.”

Rachel gave me a tight, sorry smile. “I didn’t know she was coming.”

“It’s fine,” I said, though a small knot tied itself under my breastbone.

Over lunch, Elaine delivered criticism wrapped in concern like a passive-aggressive gift basket. My cooking? Too spicy. My career? Not a real job. “When will you have real responsibilities?” she asked, dabbing the corner of her mouth with a napkin. When I mentioned our Nepal trip, she pursed her lips as if tasting something off.

“You’re not getting any younger, Julia,” she said (when she bothered to use my name, she often sharpened it). “It’s time to think about a family.”

“We have a plan,” I said, keeping my tone even. “Nepal in the fall. Maybe kids next year.”

She shot David a look—the kind that carries an instruction manual in its gaze. He shifted in his chair. He did not defend me.

“You’ve got too many mountains on your list and not enough sense of time,” she muttered, slicing naan like it had wronged her.

That night I sat with David on the couch, knees touching, TV glowing. “She doesn’t think I’ll ever give you children,” I said.

“She’s from another time,” he answered, sighing. “For her, a woman’s worth is domestic.”

“You don’t believe that, right?”

“Of course not,” he said, kissing the top of my head.

But even then, I didn’t know if he said it for me or to hear himself say the kind thing he wished were true.

Two days later, in the gym’s cool, chalk-dusted air, I clipped a nervous new father into a top rope. He was stiff, out of shape, trying and ashamed of it.

“You’ll be fine,” I said. “Most of climbing is trusting the rope.”

The class warmed, laughter echoing off high ceilings, music playing low. “Coach Julia, watch this!” a girl near the top called.

The sound came first—a small, sharp zip, as if a seam were tearing. The rope didn’t snap, not fully, but enough. The man on belay lost his footing. The fall was a story told in frames: his body twisting, the rope skidding over a biner, someone gasping, my own feet moving.

I lunged, grabbed the rope, anchored my weight. Two hundred and forty pounds hit my body like a freight train. The floor rose. The world blinked out.

When I woke, the ceiling above me was too white, the lights too bright, the smell too clean. Pain had moved in, not sharp but hollow, like something essential had been scooped out of me. A warm hand wrapped mine.

“Julia,” a voice said, low and shaking. “You’re awake. Thank God, you’re awake.”

David’s face swam into view—paleface, red eyes. I tried to speak. My throat burned. He lifted my head and held a straw to my lips.

“You took the fall,” he said when I could manage a whisper. “A student lost his grip. You saved him. But you… you didn’t land well.” He hesitated, swallowed hard. “Spinal injury. T8 and T9. They’re saying… mobility may be compromised.”

“Compromised,” my brain repeated, slow, uncomprehending, as if trying to find purchase on syllables. Like what—weeks on crutches? A cane?

A doctor came with X-rays that looked like fog and words that tasted like iron. Paralysis hung in the air like a storm cloud. Permanent. Maybe. They weren’t sure. They’re never sure. They said too early to tell, depends on your body. The truth was in their eyes.

Elaine visited the next day wearing pearls and the faint satisfaction of someone who predicted the weather then enjoyed the rain. She brought a basket of oranges and lifestyle magazines. “I told you that climbing nonsense would end in disaster,” she said quietly to David, when she thought I was asleep. She looked at me the way people look at closed stores. “And now she won’t just not give you children. She’ll need to be cared for like one.”

David said nothing. His jaw tightened. His eyes went somewhere the room couldn’t follow.

The hospital room shrank into a world measured in beeps and injections, plastic cups and the slow leak of days. I became a patient, a diagnosis, a chart that made nurses nod and men in coats sigh. Not a climber. Not a coach. A body, technically alive, lying still.

David visited every day. He brought me books and playlists like offerings to an altar. He reported what the world was doing without me. He tried to smile. It looked like work. I watched something in him dim. It wasn’t his fault. He hadn’t asked for this. Neither had I. But the fact remained standing between us like a wall.

They brought me home on a Wednesday. Our bright little apartment, once a landscape of boots and curry and laughter, had been transformed. The queen bed gone, replaced by a hospital bed with rails. A commode chair in the corner. A lift device parked by the window. The carpet ripped for easier wheel travel. The home we had made became a clinic.

The first night, David tried cheer. “We’ll get you back on your feet,” he said. “It’s a middle chapter.”

I nodded. The catheter tugged. The bag on the bed smelled faintly of lemon disinfectant. No middle chapter had ever felt more like an ending.

He learned to adjust tubes and inject meds. He googled bedsores and passive range-of-motion exercises at three in the morning. He wanted to help. He did. And with each day, he broke a little—around the eyes, in the voice. He stayed in his office longer. Sometimes I would see him sitting in the dark with his old drafting table glowing from the streetlight like a ghost of competence.

Elaine came often. She stroked his arm and said, “You’re so strong to do this for her,” as if I weren’t in the room. She had brochures for facilities that smelled like the same lemon disinfectant and called them “professional environments.” “You wouldn’t want him to burn out,” she said to me, and smiled. “Would you?”

At night, through painkillers and their soft-cloud hallucinations, I heard voices on the balcony. David whispering. Rachel murmuring. “When I’m with you, I can breathe,” he said once. I rolled back and closed my eyes so hard stars appeared under my lids.

The next morning, he brought burnt French toast—the way I liked it because my father had always burned it. I looked at the tray and then at him.

“You should tell me,” I said.

“Tell you what?” He feigned an ignorance beneath which sat pleading.

“That you want out. That I am too much.”

He sat on the bed’s edge, rubbed his face. “I don’t know how to say it,” he whispered. “I feel like I’m drowning.”

“Me, too.” My voice didn’t tremble. Perhaps I had run out of tremble.

He proposed Clearbrook Manor like a man proposing a pragmatic solution in a meeting. “Temporary,” he promised. “Until you’re stronger.”

“I’m not getting stronger,” I said.

He looked away. He said, “Let’s talk later.” But later had already arrived and put its bag down.

We packed a bag—shirts that still smelled faintly of chalk and wind; a photo of us at the top of Mount Hood—cheeks red, eyes alive; my hair in a braid, his arm around me. Rachel stopped by with tulips that would look nice by any window. She didn’t say, I’ll take care of him. She didn’t have to.

The ambulance took me at noon. Clearbrook’s lobby was beige and efficient. The walls of my room were yellowed. A crack in the ceiling shaped like a split heart gaped above me. The nurse, Valerie, had kind eyes and distracted hands. “You’ll settle in,” she said. I smiled because that was my part.

Days were a blur of measured pills, flickering lights, the shuffle of slippers in the hall. The food tasted like nothing and yet left a flavor you couldn’t name. David called at first—brief, obligation trimmed with love. “How are they treating you? Have you been outside?” He promised weekend visits that broke when they tried to land. “Work is insane,” he said. “Next week.” Next week never arrived.

A rash bloomed red and angry on my forearms. “Laundry soap,” Valerie said, handing me a cream that burned. It spread to my neck, my back. Sheets scratched. Nights were made of itch.

Part Two

I took out the Mount Hood photo. We grinned in the picture like the world had leaned in to take our side. Now, that girl felt like a fable. I didn’t cry anymore. I practiced existing in the space where the ceiling met the walls and breathed lemon air.

Then a new doctor appeared—soft steps, worn leather notebook, wire-rim glasses, a presence that did not try to fill the room just because he had a title.

“Julia Carter?” he asked, glancing at the chart. “I’m Dr. Ethan Blake. Neurorehab.” He looked at me, not past me. “I reviewed your file.” He paused, then added, “I think there’s more we can try.”

“More what?” I asked, wary of hope. Hope was a cliff. I did not have a rope.

“Rehabilitation,” he said. “Advanced methods. Not miracles. Effort.” He examined my legs, tapped reflex hammers, watched my face for flinches. “Your injury notes suggest partial compression, not full severance. You have deep tissue response. It’s quiet. But not gone.”

Everyone says maybe. He said, still.

He asked if I’d be open to unofficial sessions. “The staff’s limited,” he said. “I’ve worked at facilities that aren’t.” He smiled, a little crooked. “I can do better than what you’ve been given.”

“Yes,” I said, before logic could build a rationale around my fear.

He didn’t talk to me like I was a broken appliance. He came every afternoon after rounds, rolled up his sleeves, and greeted me as if we were resuming an interesting conversation. He learned my food cravings like a friend—fresh raspberries, buttery toast—and smuggled in a pint of the good yogurt when the kitchen sent me gray pudding. He played me R.E.M. and Sia and Simon & Garfunkel because he remembered I said Sweet Disposition made me think of unpaved trails and air that tasted green.

He showed me exercises that looked like nothing. Toe curls. Breath pacing. Visualizing movement as if your body could be tricked into remembering itself. “Neuroplasticity isn’t magic,” he said. “But it is stubborn. Like you.”

He brought in a therapist from another clinic—Marta, quiet and precise, with resistance bands in a bag and 80s playlists on her phone. We laughed in a way that didn’t feel like an apology. When nothing changed, they didn’t make me feel like nothing had. When a tingle fluttered in my right foot, Valerie called it phantom. Ethan checked it, smiled, and said, “Not a ghost.” I believed him more than I believed the lemon air.

We didn’t tell anyone about the flutter at first. We kept it like a candle you cup your hands around to protect from draft. We made a habit of trying. Slowly, I became a person who tried again.

In those afternoons, we became something else—friends. He told me about Lily, five, a girl who wore an astronaut helmet to breakfast because she needed the extra oxygen of dreaming big. He showed me a picture of her in a sparkly suit, grinning so hard the photo looked like it had light of its own. He said he wasn’t married anymore, and his voice gentled around the admission. I didn’t ask for details. I told him about David—enough to be honest, not enough to scrape the scab. He didn’t pity. He didn’t push. He listened.

One day I flexed my toes. Barely. For a second. Marta breathed in like someone seeing fireworks at noon. Ethan grinned. I cried, because it was real, because I was.

He gave me a navy journal. “Write everything,” he said. “Not polite. True.”

So I did. I wrote about rage—not just at David, but at lemon air and flickering lights and the word compromised and nurses who said honey but not I hear you. I wrote about loss—the girl on the cliff and the adulterated version of me who had agreed to be patient like a virtue instead of a weapon used against her. I wrote that losing David hurt less than realizing I had let my life be small enough for his contempt to sit comfortably inside.

Three days later, the last page of the journal—the letter I’d never intended to send—appeared on my bedside tray, printed and folded. Valerie hovered, guilty. “Found it changing linens,” she said. “Thought maybe it should… be read.”

I showed Ethan. He read, jaw tight, then said, “It’s good. And it’s yours.”

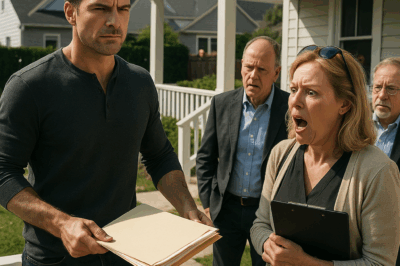

Two weeks later, David knocked on my door holding tulips and a face that had learned what mirrors were for.

“I read it,” he said. He sat, careful not to jostle the bed as if grief were a patient too. “I was a coward. Rachel was a mistake. All of it was a mistake.”

“Why are you here?” I asked.

“Because I miss you,” he said. “Because I hate who I’ve been. Because your letter made me realize I didn’t lose you the day of the accident. I lost you the day I stopped trying.”

“Do you want to fix this?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “If you’ll let me.”

“I’m not the woman you left,” I said. “I won’t be her again.”

“I know.”

“Then don’t ask me to come back. Don’t ask for before. It’s gone.”

He looked at the sink, at his hands, at the tulips he’d brought that would die in lemon air. “What do I do?” he asked finally.

“You start here,” I said, and handed him the journal. “You read. Then you figure out who you are without me. Then maybe you build something that belongs to the man you’re learning to be.”

He held the journal like it might catch fire. He nodded. He left. He did not ask for a timeline for his redemption. I was grateful.

The first time I stood was not a movie. No swelling violins. No staff gathered in the doorway clapping. Just a quiet afternoon. Marta at my elbow with a gait belt. Ethan crouched, watching tendons like a weather system.

“Whenever you’re ready,” she said.

I closed my eyes, drew air in until I felt its weight, pressed my heels down into a floor that had become more myth than friend, and pushed. My right knee snapped into a lock and trembled. My hands clamped white to parallel bars. My core screamed. I stood for five seconds. Then I sat.

I laughed in a way that echoed in the hall and made someone peer in with a frown. I didn’t explain.

By spring I shuffled with a walker from bed to window. By summer I crossed the garden with a cane. The day I left Clearbrook, I signed papers with a hand steady enough to put Julia where they expected patient. Valerie muttered that she hadn’t thought I’d make it. I smiled because I had learned I didn’t need her to think anything about me.

Ethan drove me to a second-story walk-up with scuffed stairs and light pooling on the floor like blessing water.

“This is mine,” I said as he carried a box labeled BRUSHES into a space that smelled like possibility and dust. “I signed the lease last week.”

“No elevator?” he asked.

“Always stubborn,” I said. We grinned like people who have earned the right to use that word kindly.

He paused at the door. “If you ever want—”

“I’ll call,” I said. He nodded. He didn’t make it about him.

I slept the first night without machines. In the morning, I stood—slow, trembling, fierce— and opened the blinds to let the light in. It was ordinary. It was everything.

I didn’t plan to see David again. But life loves closure almost as much as it loves open doors. I was at the community center for a wellness talk Ethan had recommended when I wandered into the café across the street afterward. I stood in line behind a man who asked too many questions about milk alternatives and then turned with my coffee and saw him. He looked older, thinner. Grayer at the temples. He saw me and his face arranged into astonishment.

“You look incredible,” he said.

“I feel incredible,” I replied.

He glanced at the cane, then at my face. He started to speak. Stopped. “I’ve been following your progress,” he said. “Ethan mentioned… I’m not the hero in your story.”

“You were once,” I said. “Not at the end.”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I know it doesn’t fix anything. I think about it every day.”

“I forgave you,” I said. “Not for you. For me.”

He exhaled like a man who had been holding his breath under water. I reached into my bag and handed him a photo. Me at Angel’s Landing: cane in one hand held aloft like a banner, the canyon behind me spilling gold.

“It’s real,” I said. “Every part.”

“You did it,” he whispered.

“No,” I said, stepping back toward the door. “I’m doing it.”

Outside, the sun poured down the street like music. I walked into it, cane steady in my hand, nothing behind me I needed to stare at to prove I had left.

I had not gotten back what I lost. I had built something new on ground I used to believe only belonged to other people. And that’s the story I keep telling when anyone asks me how I came back: I didn’t. I went forward.

Part Three

The first thing I hung on the wall of the new apartment wasn’t a mountain photo.

It was the navy journal.

I opened it to the middle—one of the less raw pages, something that said: I am not what happened to me and I am not who left me—and clipped it there with two wooden clothespins. My handwriting wandered across the paper like a trail, up and down, messy and mine.

“Statement piece,” my new neighbor said the first time she came in.

Her name was Tessa. Late twenties, curly hair, nose ring, the kind of person who introduces herself with a plate of still-warm brownies and absolutely no sense of boundaries in the good way.

“I saw you hauling boxes up the stairs with that cane,” she’d said, leaning over our shared railing. “And I thought, anyone that stubborn is either a nightmare or my new friend. I made brownies to find out which.”

She stepped into my half-furnished apartment now, balancing the brownies. “Whoa,” she said, looking at the journal page. “That’s intense.”

“That’s honest,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

She nodded like she’d file that away for later. “I like it,” she said. “Want to eat sugar and tell me your tragic backstory or save that for the third hangout?”

We ate sugar and did a condensed version. Not the whole saga—just the headline version. Accident, spinal injury, husband who couldn’t handle it, rehab, now this: a second-story walk-up with crooked baseboards and sunlight that spilled like forgiveness.

She listened without flinching. When I finished, she took another bite of brownie. “So,” she said. “You’re basically a superhero with a cane and trauma. Good to know.”

“I’m basically a woman who now needs two hands to carry groceries up a flight of stairs,” I said dryly.

“Yeah, well,” she said. “Superheroes need neighbors too. I’m down the hall if you ever need backup. Or sugar. Or to scream into a pillow.”

We became a kind of odd, patched-together family. She worked from home as a graphic designer, which meant she was always around to catch my dropped mail or press the elevator button that did not exist. I, in turn, listened to drafts of her pitches and pretended to understand conversations about brand identity and color stories.

On days when my legs felt heavy, she would knock and say, “Stair practice?” We’d take them slowly, one at a time, my hand on the rail, hers hovering behind me like a spotter.

“You know, this is like belaying,” she said once, huffing up behind me. “Except slower. And without helmets. And I’ve never done it before so maybe ignore me.”

“It is not remotely like belaying,” I said. “But points for enthusiasm.”

The building itself was a character: stained carpets, a surprising number of indoor plants, a rotating cast of hallway smells. There was Mrs. Alvarez on the first floor, who seemed to be perpetually baking something involving cinnamon. Upstairs from me lived a couple I only saw in glimpses—tattoos, mismatched socks, guitars. Somewhere down the hall, a baby periodically announced his displeasure with the world at full volume.

I had never lived alone before. Even in college, I’d had roommates and then David. The quiet of my own space took some getting used to. Some nights it felt like a blanket; other nights, more like an echo.

On those nights, I pulled out the paints.

The BRUSHES box Ethan had carried in was full of old friends: stiff bristles, dented tubes of acrylic, a mason jar with dried paint around its rim. I laid a tarp over the floor and set an easel by the biggest window and began.

At first, I painted mountains because I missed them. Ridge lines, snowcaps, the suggestion of wind. But the more I painted, the less the canvases looked like any specific place. They became impressions—large swaths of color, vertical strokes like routes on a wall.

“You’re painting your body,” Marta said when I showed her a photo at our next session at the outpatient clinic. “This one is your spine. Look.” She traced the thick band of deep blue I’d dragged up the canvas with the handle of a brush.

I hadn’t meant to. But once she said it, I couldn’t unsee it.

Ethan, when I texted him the same photo, replied: That looks like T8 is finally making friends with the rest of you.

I snorted. Only a neurorehab doctor would flirt by referencing your vertebrae.

Except he wasn’t flirting. Not really. And neither was I.

People assume that if a man and a woman spend enough time in proximity there must be a romantic arc being constructed somewhere, but what I had with Ethan was stranger and sturdier than that. He had become the person who’d seen me at my weakest and still talked to me like someone who could do hard things. That was a kind of intimacy all its own.

But intimacy is not the same as romance, and I wasn’t ready to hand over my heart like a test subject to anyone.

“Is it weird to say you’re the first person who treated me like a climber after the accident?” I asked him one day while he adjusted the footplate on a recumbent bike.

He looked up. “I never stopped seeing you as one,” he said simply. “A fall doesn’t revoke your membership.”

I swallowed. “Tell that to the part of me that still thinks in past tense.”

“I am telling that part,” he said. “Over and over. It’s my second job.”

My first official job, post-Clearbrook, came from an unexpected place.

The climbing gym. My climbing gym.

Kara, the new manager, called me two months after I moved into the apartment. Her voice on the phone made my chest tighten with muscle memory.

“We’ve been revising our safety protocols,” she said. “New ropes, new anchors, new training. We’re launching an adaptive climbing program for people with disabilities. I’d like you to consult. And, if you’re up for it, coach.”

I stared at the paint-splattered tarp at my feet. Adaptive climbing. Coaching.

“What changed?” I asked.

“You did,” she said. “You showed us the worst-case scenario and somehow you’re still standing. Also, selfishly, we could really use your brain. You helped design half the original safety system. We want it better.”

“I’m not… fully mobile,” I said. My eyes dropped to the cane leaning against the wall.

“I know,” she said. “That’s kind of the point.”

The first time I rolled back into the gym, I felt like an impostor in my own life.

The chalk dust smelled the same: a blend of sweat and magnesium and effort. The walls had changed—new routes, new color schemes—but the high, echoing space pulled memories out of my muscles like phantom pain.

Kids chattered in the corner. A group of college students stretched on mats. My eyes snagged on the wall where it had happened; the ropes there were all new, bright, unmarred. The mats looked thicker.

“Hey, stranger,” a voice said.

Kara approached, hair in a messy bun, clipboard in hand. She hugged me carefully, the way people do around a body they know has a history.

“Looks different,” I said, scanning the floor.

“Yeah,” she said. “We got a grant. New flooring. New auto-belays. Legal came down hard. We deserved it.”

Guilt flickered across her face. I’d told her in every way I knew how that the accident wasn’t her fault. We’d both signed off on the equipment. We’d done inspections. Sometimes ropes fail. Sometimes systems do everything they can and the universe shrugs anyway.

“You don’t have to do this,” she said quietly.

“I know,” I said. “That’s why I’m here.”

The adaptive program was small at first. Three participants. One double amputee, one woman with cerebral palsy, one teenager with a spinal cord injury not unlike mine. His name was Jake, and he sat in his chair slumped, hoodie up, expression carved into the universal teenage “I don’t care.”

“You any good at this?” he asked, eyeing my cane.

“I used to be great,” I said. “Now I’m weirdly excellent in a very specific way.”

He cracked the tiniest smile.

We rigged pulley systems and chest harnesses. We adjusted routes to have bigger holds, clearer paths. We talked about fear and trust and the difference between pain and discomfort. I found muscles in my voice I hadn’t used in a long time.

Halfway through the session, as Jake hung in his harness halfway up a beginner route, elbows shaking, he shouted down, “What if I fall?”

“You’re already falling,” I shouted back. “Slowly, in a harness, controlled. That’s the whole point. Keep going.”

He did. When he reached the top, he slapped the final hold so hard it made a satisfying thud. When we lowered him, his face was split open with joy.

“I forgot I could use my arms like that,” he said, breathless.

“Your body remembers more than you think,” I said. “It just needed a different sentence to read.”

On the drive home, I sat in the passenger seat of Ethan’s car and cried in a way that felt like weather breaking.

“You okay?” he asked, glancing over.

“I didn’t think I’d ever feel useful on a wall again,” I said. “Apparently there’s a version of climbing that doesn’t require being the one at the top.”

“You were never just that,” he said. “But yeah. It’s nice to see you put the chalk bag back on, metaphorically.”

Sometimes it was literal. I started chalking hands and tying knots again. I couldn’t dyno for a faraway hold anymore, but I could watch a rope run through a belay device and spot the tiniest mistake in someone’s hand position.

I went home those nights exhausted in the old way: muscles humming, skin smelling like chalk and rubber and accomplishment. I slept without nightmares.

One evening, as I left the gym, I saw a familiar car pull into the lot.

David’s.

I froze half-in, half-out of the driver’s seat of my new used hatchback. He parked crookedly, like he was more focused on what was in front of him than the white lines on asphalt.

Rachel was in the passenger seat.

My stomach did a slow, complicated thing. Not quite a lurch. More like a flip.

They saw me almost at the same time. For a brief, cinematic moment, it was like a triangle diagram.

“Hey,” David said, walking over. He looked even more tired than at the coffee shop. His eyes flicked to the gym behind me. “You’re working here again?”

“Consulting,” I said. “Adaptive program.”

“That’s… incredible,” he said. “I’m glad.”

Rachel hovered a step behind him. She looked different, too. Softer around the edges. Less like someone ready to star in her own story, more like someone who’d realized stories had consequences.

“Hi, Julia,” she said quietly.

“Hi,” I said.

No one knew what to do with their hands.

“We signed up for the couples’ beginner class,” David blurted. “We thought… it might be fun. Something new.” He gave a sheepish half-shrug. “Just trying to—”

“To build something that belongs to who you are now,” I finished for him.

He closed his eyes briefly, then nodded. “Yeah.”

I let that settle. The old me would have cut him with something sharp, pointed out how climbing had been “my thing” and how dare he bring it into his new life. The new me just saw two people trying to get better at being themselves.

“Don’t use auto-belays without checking the carabiner every single time,” I said. “And don’t look down when you’re halfway up. It’ll mess with your head.”

He smiled, small and real. “Yes, coach.”

We parted like that. No dramatic apology from Rachel. No screaming, no crying in the parking lot. Just three adults standing in front of a building with high ceilings and second chances, figuring out how to share oxygen without stealing it from each other.

When I told Ethan about it later, he nodded approvingly.

“That’s pretty mature,” he said.

“I was thinking of getting a patch for my jacket,” I replied. “Mature and surprisingly non-murderous.”

“That’s a big patch,” he said.

We laughed.

But underneath the joke was something heavier and more astonishing: I had seen the man who’d left me for another woman in the place that had once defined me, and the world had not ended.

It had just… gone on. And I had gone on with it.

Part Four

The first time someone called me “an inspiration,” I almost choked on my own spit.

It happened after a local reporter came to do a story on the adaptive climbing program. The piece ran on a slow news Tuesday, sandwiched between a segment on pothole repairs and a feel-good bit about a dog who’d learned to skateboard.

They showed a clip of me demonstrating how to rig a chest harness, cane leaning against the wall behind me, hair pulled back, chalk on my hands. They played a soundbite where I said, “Falling changed my trajectory, not my worth.”

Then they panned to Jake throwing his arms around me at the bottom of a route.

The next day, my inbox was full.

Some messages were from strangers with spinal cord injuries, asking about the program. Some were from parents of kids with disabilities. Some were from old friends, apologizing for drifting away after the accident and promising to “be there more” now that they’d remembered I existed.

And some were like this:

You’re such an inspiration!!! So strong!!!

As if surviving something I hadn’t asked for and making the best of it made me worthy of a capitalized compliment.

I forwarded that one to Ethan with the subject line: do I get a cape now or…?

He replied: only if it has a very supportive back brace.

I texted Tessa: Apparently I’m inspirational now.

She wrote back: wow, wild, I forget to wash my hair three days in a row, you learn to use your legs again, we’re basically the same.

The thing about being called inspiring is that it can flatten you. People take your mess, your sweat, your rage, and iron it into a smooth story they can hold up against their own life and say, “See? My problems aren’t so bad.”

I didn’t want to be that for them. I wanted to be something smaller and more honest: proof that a life can fall apart and still be a life.

So when a disability advocacy group asked if I’d speak at their annual conference, I said yes—with conditions.

“I’m not a motivational speaker,” I told the coordinator on the phone. “If you want someone to stand up there and say ‘Everything happens for a reason,’ I’m not your person.”

“What would you say?” she asked.

“That sometimes things happen for no reason,” I said. “And you still deserve joy afterward.”

She was quiet for a beat. “We’ll book your flight,” she said.

The conference was in Seattle, in a hotel that tried very hard to hide the fact that everything was beige by setting out bowls of citrus in the lobby. I stood behind a podium that came up higher than I liked and looked out at rows of wheelchairs, walkers, service dogs, and tired faces.

I told them the truth.

Not the cleaned-up version. The one with lemon disinfectant and bedsores and a husband who couldn’t bear to watch me not be who he’d married. I told them about the journal, about Ethan and Marta, about the first toe twitch and the first stand and the way hope felt like a foreign country.

I told them about anger—that sharp, electric current I’d tried so hard to bury because “gratitude” sounded better on a greeting card.

“I was angry at gravity,” I said. “At ropes, at gym owners, at God, at whatever set of circumstances decided that my body would hit the floor at just the wrong angle. And I was angry at myself, because if I’d done this or that differently, maybe…”

I trailed off, let the maybe hang.

“People love a comeback story,” I went on. “They love before and after pictures. But most of living happens in the during. In the slog. In the mornings when your legs feel like concrete and your brain feels like fog, and you choose, again, not to give up on yourself.”

I glanced at Ethan, sitting with Lily two rows back. She wore giant pink headphones and was drawing something that involved a lot of stars.

“I did come back,” I said. “But not to my old life, because that life required having a spine that didn’t look like a construction zone. I came back to myself. And that self turned out to like different things than I thought. She paints. She coaches. She speaks at boring beige conferences.”

Soft laughter. A woman in the second row dabbed at her eyes. A man in the back raised his fist.

Afterward, people lined up to talk. Some wanted advice. Some wanted to tell me their own stories. Some just wanted to say, “Me too,” about things we’d never thought we’d share with strangers.

One woman, maybe fifty, in a power chair with rhinestone rims, rolled up last. Her hair was dyed purple at the tips.

“I hate that word too,” she said.

“Inspiration?” I asked.

“Yeah,” she said. “I’m not a bumper sticker. I’m just stubborn.”

We grinned at each other, stubborn recognizes stubborn.

On the flight home, I stared out the window at the patchwork below and thought about how my map had changed.

There were still pins in it—both literal and figurative. I had unpinned Nepal after the accident; it felt too cruel to look at. But lately, when my brain idled, it drifted to slower visions: tea houses, prayer flags, trails that wound more gently along the foothills instead of up the faces.

“You know they have accessible trekking routes now,” Ethan said one day as we sat in the clinic’s courtyard, Lily running circles around the bench. “Not to the summit, obviously. But still beautiful.”

“Who told you?” I asked.

“Internet,” he said. “And my annoying optimism.”

I filed that away.

In the meantime, my world expanded in smaller circles.

I painted and sold a few pieces at a local gallery that specialized in “outsider art,” a label that made me laugh. “You’re very inside to me,” the owner said when I pointed it out. “But the art world needs categories. Don’t let it go to your head.”

I took on more work at the gym—training other instructors on adaptive techniques, consulting on route design. Jake got strong enough that he started trash-talking my upper body strength.

“Careful,” I warned him. “Coach still has biceps.”

My friendship with Ethan slid into something deeper and also stranger, the way a river carves a new path without asking for permission.

We texted about everything: his custody schedule with Lily, my latest attempt at baking bread (“This loaf could be used as a belay device”), his frustration with hospital administration, my anger at insurance denials for patients who needed the kind of therapy I’d gotten unofficially.

We grabbed coffee between sessions, sat in his car listening to music when I didn’t feel like going home yet.

“Do you ever think about dating again?” Tessa asked one night as we ate takeout on my floor.

“Is this your subtle way of telling me I’m spending too many Friday nights with canvas?” I asked.

“It’s my unsubtle way of asking if you’re going to do anything about the handsome doctor who looks at you like you invented hope,” she said.

I threw a napkin at her. “We’re friends,” I said. “And he’s my doctor. That’s… messy.”

“He’s technically not your doctor anymore,” she said. “You’re his success story.”

“I’m not interested in being anyone’s story ever again,” I said. “His or otherwise.”

She studied me. “You’re allowed to want things, you know,” she said. “Bodies and hearts both.”

“I know,” I said. “Wanting is not the problem. Trust is.”

We let that sit.

I didn’t bring it up with Ethan. But the question lingered in the quiet between songs sometimes.

What would it mean to risk my heart after learning it could be left in a hospital bed with tubes and lemon air?

What would it mean to trust someone not to walk away when my body might betray me again?

One chilly November afternoon, as gray rain smeared the windows of the coffee shop where we were supposed to meet, Ethan arrived looking more rumpled than usual.

“Hi,” he said, sliding into the booth. “Sorry. Patient meltdown.”

“Throwing things or crying?” I asked.

“Both,” he said. “Teenager. I said no to a risky surgery his parents wanted. They decided I was personally killing their daughter’s dreams.”

“That’s a fun position to be in,” I said.

He wrapped his hands around his mug. “I keep thinking about Clearbrook,” he said. “How close I was to just… signing off on status quo. You saved yourself, but I almost didn’t give you the tools to do it.”

I blinked. “That’s not how I remember it,” I said. “I remember everyone else settling and you refusing to.”

He shook his head. “I was tired,” he said. “Burned out. I’d been there too long. I’d started thinking of patients in terms of bed turnover. Then I read your file and something in me snapped awake. Like, if I was going to keep doing this, I had to actually do it. Not just… chart it.”

“You’re allowed to be tired,” I said. “You’re not allowed to carry my life like an example forever. Put it down.”

He smiled. “Yes, coach,” he said.

We sat in comfortable silence for a moment.

Then he said, very softly, “I know we’re… us. And I don’t want to mess that up. But if I ever ask you to dinner and I use the word date, would that be… the worst thing in the world?”

My heart did that complicated flip again.

“I don’t know,” I said honestly. “It might be the best. Or it might be… too much. I don’t trust my instincts yet.”

“Okay,” he said quickly. “Then I won’t ask. Not now. Maybe not ever. We can just be—the thing we are. It’s enough. I didn’t mean to—”

“Ethan,” I cut in. “Breathe. I’m not mad. I’m…” I searched for the word. “Tender.”

He nodded, exhaled. “That’s fair.”

We didn’t label anything. We just kept showing up. Sometimes that felt like the bravest thing I’d ever done: not slamming a door preemptively just because someone knocked politely.

Part Five

The first airplane I got on after the accident wasn’t headed for Nepal.

It was headed for Utah.

“Zion is basically StairMaster National Park,” Tessa said when I told her. “Are you sure?”

“I’m not trying to do Angels Landing again,” I said. “I just want to see red rock. Walk a little. Prove to myself the world is bigger than my zip code.”

Ethan had recommended Zion because of the accessible trails. “The Riverside Walk is paved,” he said. “The canyon walls are ridiculous. You can do as much or as little as you want.”

He and Lily were coming too. Lily, now seven, had declared herself my “official adventure buddy” after the Seattle conference, where she’d drawn me a picture of “Julia climbing the sky” and taped it to her bedroom wall.

“You sure about this?” Ethan asked at the gate, backpack slung over one shoulder, Lily clutching a stuffed astronaut.

“Absolutely not,” I said. “But I’m doing it anyway.”

The flight was uneventful in the best possible way. Lily pressed her nose to the window, narrating the changing landscape as if the pilot couldn’t see it. I did my stretching exercises in the tiny restroom, apologized to strangers for my awkward aisle shuffles, and tried not to think about the last time I’d flown with a backpack full of climbing gear and a husband who’d made jokes about airplane food.

Spring in Zion smelled like wet stone and pine.

The first time I wheeled myself out onto the Riverside Walk trail, cane tucked by my side, I almost cried just from the sight of the cliffs. They rose up on either side like the walls of a canyon cathedral, streaked with color—rust, gold, black where water had seeped and stained.

I took a breath. The air tasted like dust and possibility.

Lily grabbed my hand. “Race to that tree?” she asked, pointing at a cottonwood twenty yards away.

“I have wheels,” I said. “This hardly seems fair.”

She grinned. “Okay, no race. Just adventure walk.”

We moved slowly. I felt every dip in the pavement, every slight incline. My arms burned. It was the good burn, the kind that says you’re alive inside your muscles.

Hikers passed us in both directions. Some glanced at my chair and smiled in that tight way people do when they’re not sure if acknowledgment is kindness or condescension. Others, bless them, didn’t look at all; they just stepped around us and kept talking about their snacks.

At a bend in the trail, a group of college students had clustered by the railing, craning their necks. I heard one of them say, “No way,” and another reply, “She’s totally doing it.”

Curious, I looked up.

There, halfway up a crack in the canyon wall, was a climber.

She moved deliberately, jam by jam, her helmet bright blue against the sandstone. A rope trailed down from her harness to a belayer hidden from our view. From where I sat, she looked like an ant scaling a cathedral—but I knew, in my bones, what each movement felt like. The search for the right hold. The micro-shifts of weight. The trust.

My chest ached with something sharp and sweet.

“Do you miss it?” Ethan asked quietly, stepping up beside me.

“Yes,” I said. “And no. And yes.”

We stood there in silence, watching the climber reach a ledge and clip in, throw an arm up in victory. A cheer rose from her friends below.

Lily tugged my sleeve. “You climbed before?” she asked. “Like that?”

“Not this high,” I said. “But high enough.”

She considered this. “Now you climb other stuff,” she decided. “Like stairs. And feelings.”

I laughed, startled. “Yeah,” I said. “Exactly like that.”

We found a spot by the river and ate sandwiches from crinkly paper. The water rushed by, cold and fast, carving its own path through stone.

“Do you ever wish it hadn’t happened?” Lily asked suddenly, swinging her legs.

“The accident?” I asked.

She nodded, eyes serious.

“Yes,” I said. “I wish it hadn’t. I wish I could go back and move two inches to the left. But if it hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t be here, with you. And I really like being here with you.”

She smiled, satisfied.

That night, back at the lodge, I lay in the too-firm bed listening to the wind in the trees and thought about the word comeback.

People used it a lot, talking about me. My comeback. My journey back.

But back to what?

The life I’d had before was gone, irretrievable as an unfallen rope. I couldn’t un-live the fall any more than I could un-meet Ethan, un-move into my second-story walk-up, un-start the adaptive climbing program.

Maybe the word shouldn’t be comeback.

Maybe it should be come through.

I came through the accident.

I came through the betrayal.

I came through the lemon air and the too-bright lights and the nights where my own body felt like a foreign country.

And now I was here, in a canyon carved by persistence, with a cane leaning against the bed and a future that wasn’t a straight line but was, undeniably, mine.

The next morning, we tried a short, steeper trail. It wasn’t technically wheelchair-accessible, but there were enough flat rocks that with Ethan’s help and Lily’s commentary, we made it to a lookout.

From there, the view was ridiculous. Sheer walls dropping into green, sky a bruised blue above.

I stood.

No parallel bars this time. No gait belt. Just Ethan’s hand near my elbow, ready but not gripping, and the rock under my feet solid and rough.

My legs shook. Every scar along my spine hummed. I took one step, then another, until I stood at the edge of the overlook, both feet planted, cane in my right hand, heart somewhere above my head.

“Smile,” Tessa’s voice said in my head, even though she was back home. “This is going on the wall.”

I lifted the cane like a flag, felt the wind catch my hair, and let someone—Ethan, I think—capture the moment on his phone.

Later, when we were back in Portland, back in our regular lives of clinics and classes and grocery runs, I printed that photo.

I hung it on the wall next to the navy journal page.

So the story, in my own living room, read like this:

I am not what happened to me.

And then:

I came through anyway.

Months passed. Seasons turned the city different colors. Jake got his first job as an assistant coach at the gym. Tessa started dating a woman who wore bold lipstick and made tiny sculptures of hands. Mrs. Alvarez taught me how to make her cinnamon rolls, the dough soft and obedient under my palms.

David and I crossed paths occasionally—at the grocery store, at mutual friends’ gatherings. Each time, the conversations got easier. We talked about work, about weather, about our respective therapists. We did not talk about the hospital bed or the balcony whispers. Some things we had acknowledged and then gently placed on a shelf neither of us needed to reopen.

Once, Elaine called me.

I recognized her number and almost didn’t pick up. Curiosity won.

“Julia,” she said, voice thinner than I remembered. “I heard you spoke at some conference. People say you’re… making something of this.”

I leaned against my kitchen counter, watching the afternoon light slide across the wall.

“I am,” I said.

She cleared her throat. “I also heard… things are not easy for David,” she said. “He’s… struggling. I thought maybe you could—”

“No,” I said, gently but firmly.

She went quiet.

“I cared about him very much,” I said. “But I’m not his wife anymore. I’m not his rehab. He has to find his own way through. Like I did.”

“You make it sound simple,” she snapped.

“It’s not,” I said. “At all. But it’s necessary.”

We hung up with a stiffness that felt, oddly, like progress. I wasn’t carrying her disappointment anymore. She’d have to lug that herself.

On the anniversary of the accident, I went back to the gym alone.

No press. No fanfare. Just me, my cane, my chalk bag.

I stood in the middle of the floor and looked up at the wall where my life had changed trajectory. I touched the mat with my toes. I reached out and gripped a hold at shoulder height, feeling the familiar texture under my fingers.

“Hey, stranger,” Kara called from behind the desk. “Want a route?”

I smiled. “Someday,” I said. “Today I just wanted to say hi to the floor.”

She laughed. “Say hi for all of us. We respect her now.”

I did. In my head, in my body, I said: We have an understanding, you and I. You caught me roughly, and I survived roughly, and now we’re both still here.

When I left, I didn’t look back.

The way I came back was not a single moment, not a dramatic courtroom speech or a grand gesture. It was a long series of small, stubborn choices: to try the toe curl again, to stand one more second, to move into an apartment with stairs when elevators would have been easier, to say yes to coaching, to say no to being defined by someone else’s leaving.

If you’re waiting for the part where I marry Ethan and we ride off into the sunset with Lily on the roof rack and a dog in the back, I’m going to disappoint you.

We are… something beautiful and complicated. Sometimes we hold hands. Sometimes we don’t. We are both still learning how to love people without trying to save them or be saved by them. That learning feels as important as any summit.

Maybe someday there will be vows. Maybe there won’t. Either way, my life is not on pause until someone else presses play.

I came back.

Not to the woman who thought her worth was measured in routes conquered and photos taken at the top, not to the wife who believed being “low-maintenance” made her more lovable.

I came back to the woman who can sit in her own living room, under her own words and her own mountains, and know that she is enough even when she’s not moving at all.

After the accident, I couldn’t walk. My husband left me for another woman.

But the way I came back wasn’t by erasing those facts or pretending they made me stronger.

It was by building a life so rooted in who I really am that neither gravity nor abandonment could take it away again.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Shock! At My Dad’s Birthday Party, My Name Tag Said “The Disappointment,” They Regretted Everything.

Shock! At My Dad’s Birthday Party, My Name Tag Said “The Disappointment,” They Regretted Everything. Part One The crystal…

My Husband Destroyed the House I Grew Up In—Thinking He’d Inherit Everything. He Didn’t.

My Husband Destroyed the House I Grew Up In—Thinking He’d Inherit Everything. He Didn’t. Part One The ground where…

HOA Karen Blocked My Driveway With Her SUV — So I Flipped It Into a Ditch With My Tractor!

HOA Karen Blocked My Driveway With Her SUV — So I Flipped It Into a Ditch With My Tractor! …

‘Sorry, This Table’s For Family Only,’ My Brother Smirked, Pointing Toward…

‘Sorry, This Table’s For Family Only,’ My Brother Smirked, Pointing Toward… Part One My name’s Eli. I’m thirty-four. The…

When I Attended My Sister’s Wedding, My Seat Was in the Hallway. MIL Smirked..

When I Attended My Sister’s Wedding, My Seat Was in the Hallway. MIL Smirked.. Part One My name’s Alex,…

HOA Karen Tried Controlling My Home — But I Turned the Tables FAST!

HOA Karen Tried Controlling My Home — But I Turned the Tables FAST! Part 1 Peace, in my mind,…

End of content

No more pages to load