After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will

Part One

I never thought I’d be sitting alone in a house that suddenly felt too large, too empty, and somehow no longer mine. The grandfather clock in the hallway—the one Maxwell insisted on restoring himself despite having no experience with antiques—ticked relentlessly, reminding me that time moves forward even when our world refuses to budge. Three weeks had passed since I buried my husband, and the roses I placed on his grave every Sunday were still as fresh as the ache behind my ribs.

I’m Elellanar Witcraft—Ellie to almost everyone. At fifty-eight, I didn’t expect to be starting over. Maxwell and I had twenty-three beautiful years. We met later in life—me with an old divorce tucked like a scar beneath my clothes, and Maxwell with three nearly grown children who never quite forgave me for existing. Our wedding at Azure Bay was small and tender. His children—Piers, Bianca, and Xavier—stood stiff in tailored clothes, offering congratulations that clinked like glass. For years I tried to bridge the gap: holidays, birthdays, graduations. I never stopped trying. Eventually, I learned to stop hoping.

Maxwell died at his desk at Witcraft Industries. One moment he was finalizing an acquisition; the next, a heart attack put a full stop where there should have been a comma. I wasn’t even granted the indignity of goodbye. The funeral blurred past in black fabric and murmured sympathies. I remember resting my hand on the polished wood of his casket and feeling as if I’d been placed gently outside my life and told to watch it from there.

Exactly one week after the funeral, his children descended on Hion Estate as if the summons had chimed on their phones.

“Ellie,” Piers began—tall, groomed, eyes screened behind expensive sunglasses. “We need to discuss the estate.”

Bianca crossed her legs on the fainting couch and let her gaze sweep the room as if cataloging flaws. “We’ve been patient—grief, of course—but certain matters can’t wait.”

Xavier drifted, picking up objects and putting them down in slightly different places, weighing them in his hand. “Dad hated loose ends.”

I poured tea. They didn’t accept, so Josephine brought the tray anyway, her eyes catching mine: I’m here. “What matters?” I asked.

“Father’s will,” Piers said. “The reading is tomorrow at Blackstone Law. We wanted to speak first, to ensure a smooth transition.”

“Transition?” The word tasted like varnish.

“Witcraft Industries is our birthright,” Bianca said simply. “We’ve worked there since university.”

That was only partially true, but today I counted to three instead of correcting her. “Maxwell never discussed specifics,” I said honestly. “He told me everything was taken care of.”

Xavier snorted. “Come on, Ellie. You must have some idea—jewelry, a stipend, the cabin in Vermont.”

These were adults who had known me for more than two decades and still managed to speak as if I were a weekend wife. “We’ll all find out tomorrow,” I said evenly.

“We should also discuss your living arrangements,” Piers added. “Hion has been in the Witcraft family for generations.”

“It’s where we grew up,” Bianca said with the delicate cruelty of someone who thinks she’s being gentle. “It holds tremendous sentimental value for us.”

“We’ve lived here twenty years,” I replied. “This is my home.”

“It’s a Witcraft family property,” Piers corrected. “We’re suggesting you might be more comfortable in a smaller place. The maintenance must be overwhelming for someone…” He let the rest hang in the doorway with his sunglasses.

“My position?” I said. Widow. Childless. Aging. “I manage quite well. Josephine has been invaluable.”

As if she’d been waiting in the wings for the cue, Josephine appeared. “Will there be anything else, Mrs. Witcraft?” she asked—Mrs. Witcraft, as if it were a shield. The stepchildren exchanged glances. Xavier tried on concern like an expensive coat. “You could stay with friends until everything is settled. The reading can be emotional.”

For twenty-three years I’d swallowed remarks and made excuses, told Maxwell it didn’t matter. But Maxwell was gone, and with him went the last thin layer between patience and spine. “I’ll be staying right here,” I said. “This is where Maxwell wanted me.”

“We’ll see what Father wanted tomorrow,” Piers said, already standing. Bianca paused at the door. “We had some boxes delivered—just in case you’re ready to organize your personal items.”

The cars purred away. When the gravel stopped speaking, Josephine did. “Vultures,” she said, her Jamaican lilt unsoftened for once. “Didn’t even wait until Mr. Maxwell is properly laid to rest.”

“They’ve been waiting for this day,” I said, staring at untouched cups. “Waiting for him to stop taking the sharp edges.”

“Mr. Maxwell knew his children,” Josephine murmured. “More than they think.”

Maybe. But Maxwell also believed his forgiveness could change anyone.

That night I walked the geography of our life: his glasses on the nightstand, the half-used cologne, the leather slippers sagged to his feet. For the first time since the funeral, I opened his closet and pressed my face into his shirts. There, behind a row of suits, I saw a small safe I’d never noticed. We had a shared safe in the study—but this one was hidden, personal.

I tried our anniversary. His birthday. The day we met. The year Hion was built. Nothing. I rested my forehead against the cool metal. “What were you hiding, Max?”

Sleep, when it came, eyed me like a stranger. I dreamed of Hion emptied to the studs while voice-less movers rolled away the walls.

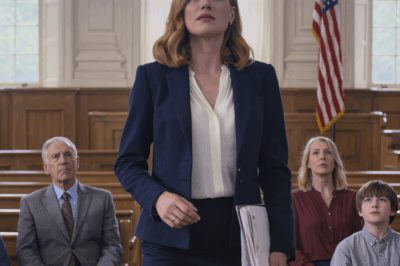

I dressed for the will reading as if for battle: the navy suit Maxwell loved, my pearl strand, his mother’s diamond brooch—the first gift he ever gave me. Josephine insisted on driving. “You shouldn’t be alone today,” she said, which meant, I’m not leaving you alone with them.

Blackstone Law’s Victorian grandeur smelled like leather and polished wood. Dr. Theodore Blackwood’s assistant led us to a conference room where the stepchildren were already arranged, along with Margot Chen—Maxwell’s business partner of thirty years. Margot rose to embrace me. “Ellie, my dear.”

Before I could answer, Dr. Blackwood entered: tall, silver hair, kindness behind wire-rimmed glasses. “Before we proceed,” he said, setting his briefcase on the table, “Maxwell asked that I read a letter privately to Mrs. Witcraft.”

“That’s highly irregular,” Piers snapped.

“Your father’s instructions were explicit,” Dr. Blackwood replied. “We can wait. Or reschedule.”

“Maxwell’s wishes will be respected,” Margot said sharply, and that was that.

In his book-lined office, Dr. Blackwood broke the seal.

My dearest Ellie,

If you’re hearing this, I’ve left you too soon. You’re about to face a storm. My children have never understood that you were the best part of me. They see Witcraft as inheritance, Hion as birthright, and you as an obstacle. Fifteen years ago the company would have collapsed without your intervention. You stayed up nights, found the discrepancy, built the restructuring plan that saved thousands of jobs. You insisted I take credit. You were right about how they’d resent you.

The will they’re about to hear is not my final word. It is a test—one last chance for decency. Watch them carefully. Trust Theo. Trust Margot. Trust Josephine.

All my love,

Maxwell.

“Two wills?” I whispered.

He nodded. “The second activates under conditions Maxwell specified.” His eyes warmed. “Everything from this point is by his design.”

Back in the conference room, the air tasted like pennies. Dr. Blackwood began reading:

To my children, jointly, control of Witcraft Industries and all associated holdings. To my children, equally, Hion Estate and all other properties—except the Vermont cabin, which goes to my wife, Elellanar. To my wife: a modest stipend, personal possessions, and residency at Hion for ninety days to organize her affairs. During those ninety days, the property and its contents remain in trust. Any contestation results in forfeiture.

Piers actually patted my hand. “Father was generous, considering.”

Bianca began outlining redecoration plans before the ink dried; Piers texted the board. Xavier made a little show of not reacting and thereby reacting completely.

“Dr. Blackwood,” I said softly, “I have one question. The Vermont cabin—can I move there immediately?”

“You can,” he said. “It transfers to you now.”

“Good.” I stood. “I’ve heard enough.”

Margot followed me into the hall. “Don’t let them see you broken,” she said in a fierce whisper. “Maxwell had his reasons.”

Outside, Josephine opened the car door. “They got everything,” I said.

“Almost everything,” I corrected myself, thinking of the hidden safe, the letter, the second will. “We have ninety days. And then we see what Maxwell planned.”

As we turned into the drive, blue lights flashed against Hion’s façade. A plain-clothes detective waited on the porch. “Mrs. Witcraft? Detective Vincent Caldwell, Ravensdale PD. I’m sorry to intrude. I need to speak with you regarding your husband’s company.”

“What about it?”

“Financial irregularities,” he said. “We believe your husband may have uncovered something significant before his death.”

Pieces began to shift. Maxwell, working late. The hidden safe. The letter about the restructuring only I knew I’d done. “Perhaps inside,” I said.

In Maxwell’s study, Caldwell refused tea and settled with his notebook. “Were you involved with Witcraft Industries?”

“Not officially.”

“Are you aware that fifteen years ago the company underwent a restructuring widely considered miraculous? The strategies were not in line with Maxwell’s usual approach.”

“Maxwell was adaptable,” I said, choosing each word.

He nodded, not convinced. “We’re investigating unusual transactions: large sums moving through shell companies, investments designed to fail, a pattern suggesting deliberate sabotage.” He leaned in. “The night Maxwell died, he had scheduled a meeting with me for the following morning.”

“Do you know what he planned to show you?”

“I was hoping you could tell me,” he said. “Did he store documents somewhere secure?”

The hidden safe flashed in my mind, but I kept my face steady. “He sometimes brought work home,” I said. “I can look.”

After he left, Josephine came to the study doorway. “You didn’t tell him about the safe,” she said.

“He didn’t tell me everything either,” I said. “He knows more.” I looked around the room—the desk, the piano, the grandfather clock—and felt the house lean toward me like a story waiting to be read.

We went straight to the bedroom. “All these years,” Josephine murmured, touching the hidden door. I tried numbers—our anniversaries, the year we met, the house’s completion. Nothing.

“Azure Bay,” Josephine said suddenly. “The day you first went there together.”

Of course. 10-17-1. The tumbler clicked; the door swung open. Inside: a single USB drive and a folded note: For Ellie’s eyes only. Password is where I first called you my heart.

I knew the place and the night: a storm, candlelight when the power failed, a chocolate soufflé collapsing as the waiter set it down, Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata clipping through the darkness. I typed the title. The file opened into a neat architecture of folders: spreadsheets, emails, videos. The most recent: for Ellie.mp4, dated the day before he died.

Maxwell’s face filled the screen—tired, resolute, eyes warm even under the weight. If you’re watching this, I either told you or I’m gone, he said. Someone is looting Witcraft from within. It’s my children. They built a network of shell companies, they’re siphoning funds, they’re destroying what we built. I’ve compiled evidence. I meet Detective Caldwell tomorrow. If anything happens, continue the work. Trust Theo, Margot, Josephine. The will Theo reads first is a test. I don’t hold much hope. My greatest regret is not standing up for you more fiercely. Follow the evidence. Remember: Hion was never just a house. Hion was wherever you were. I love you, my heart—always.

We worked for an hour gathering the essentials. Bank statements with Maxwell’s crisp notes. Fake invoices. Emails between the siblings discussing their father’s “timeline.” Threats against employees who asked questions. The security chime announced visitors. On screen: three cars in a row—Piers, Bianca, Xavier.

“Perfect timing,” I said. “Make copies. I’ll greet our guests.”

By the time I reached the foyer, they’d already let in a young man with a tablet. “Inventory,” Piers said smoothly. “Nothing to worry about.”

“The trust conditions are clear,” I said. “Ninety days.”

“We’re simply assessing,” he replied. “Marcus from Sabes is documenting the valuables.”

Xavier turned a Ming vase over in his hands as if its worth rose from his palm. “This alone—”

“Careful,” I said lightly, and put my fury in a drawer.

“What about your father’s personal things?” I asked. “Photos, books. His slippers.”

They hadn’t considered them. “You can have all that,” Bianca said, magnanimously. “Focus on the sentimental. We’ll handle the significant.”

“Well then,” I said, with the practiced meekness of someone who has watched bad actors until she learned the steps. “I’ll stay out of your way.”

From Maxwell’s desk I watched through the window as more cars arrived: movers, appraisers, even a landscape architect measuring my rose beds. My phone buzzed: Files copied. Caldwell called. Glass Pavilion at noon. It was almost funny that the password and the meeting place matched.

In a drawer I found the leather journal I’d given Maxwell years ago. Not business notes—sketches of me: reading, laughing, sleeping, soft lines signed with a tiny heart. The last entry was words, not lines: I’m almost done. I pray she understands why I kept it from her. It’s all for her—so she’s secure, vindicated, and free from their machinations forever.

Xavier barged in without knocking. “We need the combination to the safe,” he said. “The one in the closet.”

“How did you—” I caught myself. “I wasn’t aware of any safe.”

“Don’t play dumb,” he said. “We’ll get a locksmith.” He left the door open behind him like an insult.

I texted Josephine: Call Margot. Tonight. Not here. I gathered Maxwell’s journal and a handful of photos and tucked them into my bag.

By evening the first floor was a confetti of red stickers. “We’ll continue upstairs tomorrow,” Piers announced. “Master suite, guest rooms, attics.”

“Dinner?” I asked. “I can have Josephine—”

“We have reservations,” Bianca said. “Business dinner.”

“Of course.” I watched their taillights disappear, then hurried to the kitchen where Josephine waited. “Margot can meet us on her houseboat,” she said. “Eight. Private dock entrance.”

Margot lived on a sleek floating sanctuary named Autonomy. She helped me aboard and handed me whiskey. “Drink. Then tell me everything.”

I did: the will reading, Caldwell’s visit, the hidden safe, Maxwell’s video, the inventory invasion. “Those ungrateful parasites,” she said—then softer. “Maxwell was investigating, too. Three months ago I found numbers that made no sense. I told him. He told me about the contingency plan.”

“The second will,” I said.

She nodded. “You’ll control Witcraft with me as co-executive until you decide to keep or sell. Hion becomes yours outright. The children get reduced inheritances—enough to live, not enough to build empires.”

“When does it activate?”

“Three triggers,” she said. “Theo knows the exact legal wording. But I know this much: if they violate the trust by claiming Hion or its contents before ninety days; if evidence of their criminal activity emerges; and…” She studied me. “If any harm comes to you. Maxwell feared they might see you as an obstacle.”

“They broke into the safe,” I said. “They’ll guess I have something.” I set down my empty glass. “What do I do now?”

“Play the defeated widow,” Margot said. “Meet Caldwell tomorrow and give him Maxwell’s files. Theo will handle the will. Maxwell built a fortress around you. They just don’t know it yet.”

We stopped at Westlake Security on the edge of town. Inside the unit: file boxes, drives, recordings, surveillance photos of Piers in parking garages. “We can’t take it all,” I said, filling a bag with the essentials. “But we can take enough.” Josephine suggested her cousin’s vacant cabin on Lake Merritt. We drove through the dark.

By dawn I knew more about betrayal than I’d ever wanted to learn: stolen technology, falsified expenses, blackmailed employees. I showered and we went to Dr. Blackwood’s office before it officially opened.

“The second will activates if they violate the trust,” he confirmed, “or if criminal activity emerges, or if you come to harm. Yesterday’s inventory likely triggers the first. If Caldwell accepts Maxwell’s files, that’s the second.”

“What does the second will say?” I asked.

He slid an envelope across the desk. The document inside was simple, devastating, and kind. Witcraft Industries to me, with Margot as co-executive until I chose a course; Hion and all properties to me outright; modest trusts for the children; and half of Maxwell’s fortune to a foundation in my name to compensate employees harmed by the fraud and to invest in ethical business practices.

“This will destroy them,” I whispered.

“It will give them what they’re owed,” Dr. Blackwood said gently. “Maxwell was generous even here.”

“File it,” I said. “I’ll see Caldwell at noon.”

We chose the Glass Pavilion because that’s where Maxwell would’ve chosen—where he once called me my heart with candlelight and stormwater on the glass. We spread the files across the private dining table. When Detective Caldwell arrived, he read in silence, jaw tightening. Twice he stepped into the hall to call someone. “This is far worse than suspected,” he said. “Multiple federal charges. I’ll move now.”

“What if they run?” I asked.

“We’ll have eyes on them,” he said—and he did. By evening, the news showed police at Witcraft headquarters. Agents carried out boxes. Piers, jaw a line of granite, was marched through the lobby; Bianca argued and lost. A text from Caldwell: Warrants executed. P&B in custody. X missing. Stay put.

We didn’t. But that was tomorrow’s mistake to make. Tonight I stared out at Lake Merritt, phone warm in my hand, Maxwell’s voice in my head: Follow the evidence. Trust Theo. Trust Margot. Trust Josephine. Hion was never a house; Hion was wherever you were.

I had been afraid surviving would feel like betrayal. But in the quiet of the cabin, between the heartbeat of lake waves and the slow breath of pines, I realized surviving was the only way to keep my promise to him.

Part Two

Agent Sarah Kamura from the FBI knocked at dusk with coffee and a badge. Caldwell had sent her, she said; Xavier had vanished before the warrants landed, and men with nothing left to lose sometimes look for someone to blame.

“We’ll move you if necessary,” she said gently. I thought of Josephine asleep down the hall and of Hion—its silent rooms, its stolen stickers. “Tomorrow,” I said. “First I need to see Caldwell again.”

He was waiting at the station with a folder of new horrors. “They weren’t just stealing,” he said, sliding a draft agreement across his desk. “They were dismantling Witcraft to sell its bones to a corporate raider. This was in motion three months before Maxwell died.”

“Which means they knew,” I said.

He nodded grimly. “And there’s more: evidence they aggravated Maxwell’s heart condition—stress triggers, withheld monitoring. Legally complicated. Morally? Murder.”

Then he placed a second document in front of me—a genetic test. “Maxwell compared his DNA to his children’s.”

I knew before I read the conclusion. I felt it in the room.

“Piers and Bianca are biologically unrelated to Maxwell,” he said. “He raised them anyway. Xavier is biologically unrelated to Maxwell as well.”

Shock rippled through me anyway. Later, I would learn the truth hid behind the wording: the test had been run against Maxwell’s legal records, not his private past. But at that moment, the conclusion stood on cold paper: no biological heirs.

“Does Xavier know?” I asked.

“We believe he learned weeks ago. That may be why he bolted. It also makes him more dangerous.”

I thought of Hion, its clocks and careful dust. “I want to go home,” I said.

“Mrs. Witcraft—” Agent Kamura began.

“It is my home,” I said. “And I am done being pushed.”

They compromised: a security sweep, patrol cars, Kamura in the driveway. When we pulled up, the front door hung a fraction open. Kamura drew her weapon and disappeared inside. The house settled around me like a held breath until she reappeared. “All clear,” she said, “but someone’s been here.” The signs were small—misaligned books, shallow drawers, a rug not sitting right—but unmistakable.

“They were looking for the files,” I said. “Too late.”

I called Josephine—assured her I was with agents, told her to wait until morning. Kamura’s phone chirped. “Local police sighted Xavier at the marina,” she said. “Houseboats.”

“Margot,” I said, the word exiting as a plea. She dialed. No answer.

“I’m coming,” I said.

“You aren’t,” she said.

But Margot had stood in a hallway and told me Maxwell had his reasons. She had handed me a key to a storage locker. She had poured me whiskey and called his children parasites. And now she was not answering.

“I’m coming,” I repeated.

We reached the marina in minutes. Officers had already cordoned off the private dock. Security footage showed Xavier boarding Autonomy after speaking briefly with someone—someone slightly out of frame with silver hair and a composed posture.

“Let me call,” I said.

Kamura hesitated and then nodded. “On speaker. We listen.”

Margot answered. “Ellie,” she said, and her voice was normal, steady, entirely wrong. “We’re talking. We’re fine.”

“Are you safe?” I asked.

“Perfectly,” she said. “Perhaps you should join us. There are things you need to know. Things Maxwell kept from all of us.”

The line went dead. Kamura’s jaw tightened. “Either she’s under duress,” she said, “or she’s not the ally you think.”

“Or the truth is complicated,” I said. “Which is the only truth I’ve had lately.”

I didn’t wait for permission. I took a wire and a code word and a twenty-minute limit. Then I walked down the dock to where Margot stood waiting in a white blouse and a look I’d seen in boardrooms when deals were about to land.

Inside the salon, Xavier sat in an armchair with a drink he turned in his hands. He looked up, and in the shape of his eyes, I saw Maxwell—something about the way the corners crinkled when he thought too hard. That, more than anything, told me whatever was coming was going to hurt.

“No games,” he said. “You’re wired. Fine. We’re past games.”

Margot slid a portfolio across the table. “Maxwell’s original will,” she said. “Five years old. Before the fraud. Before you. Page fourteen.”

Thirty percent of Witcraft to Margot. The rest to the children.

“He changed it,” she said evenly. “When he wrote the second will—the one you now hold—he cut me out, gave my share to you.”

“Why show me this?” I asked. “It’s void.”

“Because what he did next only makes sense if you know what came before,” she replied—and drew out a sealed envelope. In the event of my death, to be destroyed unopened.

“Maxwell kept this in his private office safe,” Margot said. “The FBI let me collect company documents. I found it and—no, I did not destroy it. I needed to know why he cut me out.”

“Read,” Xavier said.

The letter was dated six months earlier. It was not a will. It was a confession wrapped in tenderness:

Thirty years ago we made a decision that altered three lives. We chose to let Catherine claim the baby as hers, to give him a name and a home. Your career was just beginning; a child would have derailed it. We told ourselves it was for the best. I’ve watched our son grow without ever calling him mine. It broke me and I let it break me because I believed it would be better for him. I can’t tell Ellie. She deserves the man she married, not the mess I made before her. If this letter exists, I have failed to do the kind thing—to burn it.

I looked up. “Our… son,” I said, the words catching.

Xavier’s mouth twisted. “I am Maxwell’s biological child,” he said softly. “Margot is my mother.”

The room shifted. Tables slid imperceptibly out of place. In the distance, I heard the marina’s halyards sing against masts as a gust of wind moved through the forest of sails.

“Catherine was already cheating,” Margot said with clinical calm. “Piers and Bianca had other fathers. Her last affair gave us cover. Maxwell’s marriage was crumbling. My career was finally catching fire. We made a choice. It was the wrong one—perhaps the only one we could make—but still wrong.”

“Why now?” I asked. “Why this?”

“Because I want what I earned,” she said simply. “Thirty percent of the company, restored. In exchange, I keep this private. I invoke my silence on behalf of your grief.”

“Blackmail,” I said.

“Business,” she replied.

Xavier looked at me with something like apology buried under old anger. “I learned the test result weeks ago. I thought I was no one. Piers and Bianca used me like kindling. I helped them because if I wasn’t a Witcraft, why not take what I could from the lie?”

“He didn’t tell you the rest,” I said. “That you were his son. That he had loved you in the only way he thought he could.”

“He told himself that,” Xavier said bitterly. “He never told me.”

Margot tapped the portfolio. “You can set this right. Restore my cut. Keep the second will. Help Xavier with a plea deal. Or we let the world devour the romance of Maxwell Witcraft and use your widowhood as seasoning.”

I thought of the foundation Maxwell created in my name, the employees he wanted to protect, the truth he asked me to carry. I felt the clock in my chest move forward one tick.

“No,” I said.

Margot blinked. “You’re not thinking clearly. The media will crucify him—and you.”

“I don’t care,” I said. “I loved the man I had, not the one in a press release. He made mistakes. So did you. So did I. But he chose me to finish this. I won’t trade that for hush money.”

I turned to Xavier. “You were hurt, so you chose to hurt everything. Maxwell raised you. He fed you and educated you and forgave you. Biology doesn’t absolve you. It indicts you.”

He flinched. “You don’t—”

“I do,” I said. “And I will say so in court if I have to.”

Footsteps glided above—the soft code of a tactical team changing posture. Kimura appeared in the doorway with officers behind her. “Time,” she said.

Xavier stood, wrists offered. He looked at Margot, then at me. “She’s just like him,” he said quietly. “Stubborn. Principled. Unwilling to sell the truth even when it’s cheaper.”

“Perhaps that’s why he chose her,” Margot said, and for the first time that day, her voice wobbled.

On the dock, media gathered like gulls. Caldwell met us at the gangway. “Are you all right?”

“Yes,” I said—and I was surprised to find it true.

“What did she want?” he asked, jerking his chin toward the boat.

“Things that are not evidence,” I said. “Things that belong to the part of the story no one can prosecute.”

He studied me and then nodded. “Statement tomorrow. Prepare for attention.”

I went home.

The house smelled like lemon oil and old paper. I placed Maxwell’s letter and the original will in the desk drawer and locked it. I poured two fingers of his scotch and sat in his chair where the moon silvered the gardens he planted and I kept alive. Hion had never truly been mine; it had belonged to his first wife’s memory, to his children’s condemnation, to the past tense. Tonight it felt like the place where I could begin writing the present.

In the morning, Josephine returned with a basket of still-warm muffins and a look that dared the world to try her. We walked through the rooms together. We peeled off the red stickers and set them in a neat line on the hall table. When we finished, I called a charity I loved and arranged for a truck. “Take the lot,” I said. “We’ll keep what feeds the soul.”

That afternoon I met the Witcraft board. Margot did not attend. I placed Maxwell’s second will on the table and explained the order of the next months: audits, restructuring, a new ethics office with teeth, board seats deferred until external monitors approved. I introduced the foundation and wired its initial funding. “We will make whole those we hurt,” I said. “We will recalibrate what profit means.”

Piers and Bianca were arraigned. Bail denied. Headlines sprouted from every channel and horned through comments sections where strangers pulled apart my life in exchange for outrage clicks. I did not read them. I wrote a statement: Witcraft Industries will survive. Our employees will be protected. Our wrongdoing will be addressed. Our future will be different. My husband loved this company and his family, imperfectly, fully. I intend to honor both truths.

Caldwell took my formal statement. Kamura shook my hand and told me to call if the world felt too loud. I asked Josephine to move back into Hion because Home needs a witness. We hired a security firm that understood discretion and sightlines. Dr. Blackwood brought me forms to sign and a stack of letters to read. I signed the ones that required it and read all the rest.

A week after the arrests, I went to Azure Bay alone. The sea rolled and withdrew, rolled and withdrew. At our table under the glass, I ordered a chocolate soufflé and listened to the piano player’s hands slide into Moonlight Sonata. I set Maxwell’s letter on the table and read it once more and then slid it back into my purse. I did not burn it. Kindness sometimes lies; truth sometimes wounds. I no longer had the luxury of protecting everyone. I had a company to save, a house to keep, a life to write.

On the drive back, the oaks along the lane threw shade like lace. The grandfather clock chimed as I pushed the door. I paused in the foyer and looked up the staircase where I had once called for a man who would never again answer. The house exhaled around me as if it, too, had been holding something. I whispered into the air: “I kept my promise.”

The work ahead was ordinary and enormous: HR forms and legal meetings, trauma counseling for employees, replacing a chandelier the appraisers had claimed, switching out passwords, choosing new paint for a room that felt like a bruise. I deleted numbers from my phone and added others. I learned the names of the security guards at the gate and brought them coffee because people who keep watch deserve warmth. I took off my wedding ring at night and put it on each morning. Grief became an act of daily maintenance, like watering a difficult plant that surprises you by blooming.

As for Margot, she issued her own statement: regret couched in corporate sorrow, personal matters that did not concern the public. She resigned from her board seats at Witcraft and three other companies. Caldwell told me her lawyers were excellent and her timing better. I did not respond. Xavier pled to reduced charges and agreed to testify against Piers and Bianca. I did not rejoice. Grief’s algebra never results in clean answers; even justice leaves a remainder.

On a bright afternoon in late autumn, I stood on the back steps with a mug of tea and watched Josephine cut the last of the season’s roses. She tied them with kitchen twine and pressed the bouquet into my hands. “For the desk,” she said. “Where he wrote to you.”

“Where we write back,” I said, and placed the roses beside the leather journal full of sketches of me I hadn’t known he was making.

I sat, opened my laptop, and drafted a new document titled Hion Foundation—First Year Plan. It wasn’t a love letter. It was better: a blueprint for a different kind of inheritance.

The grandfather clock ticked. The house was still large, still sometimes too empty. But it was mine—not as a monument to anyone’s past, but as a staging ground for what comes next.

Whatever came, I would meet it the way Maxwell taught me without ever saying the words: stay, look the truth in the face—even when it’s your own—and then do the next necessary thing.

Part Three

The morning after I reclaimed Hion by peeling off the appraisers’ red stickers like scabs, the house felt less like a mausoleum and more like a patient waking. Light made its slow progress across the foyer tiles; the grandfather clock ticked as if it had only ever meant comfort. I dressed the way you dress for a day that will require both spine and softness—dark trousers, a white shirt with French cuffs, Maxwell’s cufflinks like a private benediction—and drove to Witcraft headquarters with Josephine’s coffee in a thermos and her blessing like armor: Go, Miss Ellie. Make him proud.

Headlines had done what headlines do. A pack of cameras waited beneath the atrium’s glass prow, flanked by employees doing that particular corridor walk—the one that says, We still have work; we still have a paycheck; we still don’t know where to look. Detective Caldwell stood just inside the revolving doors with Agent Kamura at his shoulder, a still center in a swirl of noise. “You ready?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “But I’m here.”

We took the elevator up. On twelve, the boardroom smelled like carpet cleaner and old grief. Seats were already filled: directors with law degrees tucked into their chins; two union reps with faces like weather; the interim CFO whose hands shook before he smoothed them flat. A floral arrangement drooped in the corner, overwatered contrition. Dr. Blackwood waited at the head of the table, file boxes at his feet like footnotes.

“We will proceed formally,” he said. “And plainly.”

He read Maxwell’s second will into the corporate minutes.

It was not theatrical. There were no gasps or fainting chairs. There were objections—muttered, then spoken, then wrapped in Latin—and there were questions about fiduciary duty and valuation and the board’s obligations under regulatory oversight. I answered each as if I had practiced in a mirror: We will cooperate with all monitors. We will retain outside ethics counsel with authority to fire anyone, including me, if necessary. We will make the harmed whole where the law allows and the conscience demands. We will not sell this company for scrap to atone for a crime committed by people who treated it like a personal ATM.

“And the children?” a director asked, either brave or foolish.

“In custody, cooperating, or counselled,” I said. “And not in this room.”

Union Rep Morales leaned forward. “Our people want to know if they should polish their résumés.”

“They should update them,” I said. “And they should also expect to receive paychecks on Friday.”

A breath moved around the table like an incoming tide. It did not absolve me of anything. It simply let me sit without my spine catching fire.

After the meeting, I walked the floors. I did not give speeches. I asked names and wrote them down. In the design lab, a young engineer showed me a prototype that would cut material waste by twelve percent. In Shipping, a woman with a back brace like mine from a life ago told me she could do three people’s jobs if the conveyor belt didn’t catch her sleeve every time she leaned. “Don’t be a hero,” I said. “Be here. We’ll fix the belt.”

Back at Hion, I found Dr. Blackwood waiting in the study with a leather case and a look that suggested he’d read two chapters ahead. “Your husband left one more letter,” he said. “Not for court. For you, if and when you asked for it.”

I did not ask; I simply opened the case and took the envelope addressed in Maxwell’s left-slanted hand: For the day after the storm.

My heart,

If you’re reading this, you chose to stand. That’s the only thing I ever trusted in the world: that you would stand—sometimes in a room alone, sometimes in a room full of people who mistake volume for virtue—and choose the next right thing. If the children are angry, let them be angry somewhere else. If Margot is righteous, remember she has always believed the story in which she is the exception. If the board wavers, build them a bridge of facts sturdy enough to carry cowards. And if you doubt, come back to Azure Bay and eat a chocolate soufflé and listen to the Moonlight and remember we are particles and waves and it is all right that it feels like both.

You once told me houses remember. I have watched Hion remember you for twenty-three years.

—M

I folded the letter back into its envelope and pressed it flat with my palm, as if smoothing a sheet over a sleeping body. Then I turned to the work.

Caldwell called at dusk. “Plea talks,” he said. “Xavier’s counsel reached out. He’s willing to admit to conspiracy and aid in recovery in exchange for a reduced sentence.”

“He tells the truth about the sabotage and the shell companies,” I said. “All of it. He apologizes to the employees in open court. Not for me. For them.”

Caldwell paused. “You’re going to testify?”

“Yes,” I said. “And so will Dr. Blackwood and any file cabinet Maxwell ever touched.”

“Then get some sleep,” he said. “It’ll be a marathon, not a sprint.”

Sleep arrived like a truce. At three in the morning, I woke to the sound of the grandfather clock and a thought so obvious it felt like someone else had put it on my pillow: The clock. Maxwell had insisted on restoring it himself, to Josephine’s horror. He’d sworn there were “pockets” in the case that only the builder would know.

I padded down the halls in bare feet, a flashlight in my teeth and a screwdriver in my hand. The clock loomed in the moonlit foyer, dignified, unbothered. I knelt and removed the lower panel. Inside, behind the pendulum’s brass solemnity, was a narrow felt-lined recess. My fingers found an envelope and a key. The key was brass, old, stamped with the letters HL—Hion Library. The envelope held a card, one sentence in Maxwell’s hand: Look where we began.

The library had begun as a room full of show spines—leather without life. Over the years, we had traded veneers for paperbacks with broken backs and margins full of our arguments. I ran my hand along the third shelf where we kept early loves—Austen, Baldwin, Morrison, a first edition of a poet we’d met by accident in a tiny shop in Prague. The key slid into a nearly invisible seam, and the shelf clicked forward. Behind it, a shallow wall safe I had never noticed.

The combination was the date on the back of an old photograph clipped to the inside of the door: the day we moved me into Hion, signed by Josephine—You are home, Miss Ellie. Inside: deeds, bearer bonds long out of fashion, a velvet box, and a sheet of paper headed Foundation Schedule A.

The velvet box held a brooch I had never seen—diamonds in a constellation pattern—accompanied by a note: Your mother-in-law would have wanted you to have this, not the girl who thinks grief is a brand. The schedule listed philanthropic bequests tied to the second will: scholarships for employees’ children; grants for small manufacturers that pledged to keep their supply chains clean; a fund for whistleblowers who would never work again because they did the thing they tell you in grade school to do.

I sat on the rug and let the stupid, generous thought occur to me without punishment: He believed I could do this.

The trials began in late winter, when the sidewalks held gray islands of old snow and the courthouse radiators hissed like tired snakes. The state proceeded first—embezzlement, fraud, conspiracy. Federal prosecutors hovered with their own alphabet soup. Piers perfected a martyr’s stoop; Bianca wore the wardrobe of a woman whose stylist had whispered too much absolution. Xavier sat small at the defense table and tried to look like a person who had discovered the floor.

I took the stand and did not speak like a woman on television. I spoke like a woman who had spent nights with spreadsheets and glow-in-the-dark pens. I explained what I knew about the shell companies, how invoices whispered their lies if you listened to date stamps and vendor addresses. I told the court about Maxwell’s late-night coffee, the jitter in his handwriting in the weeks before he died, the way he looked up from the ledgers and said, “They think I’m old.”

The defense attempted character assassination by adjective—widow, stepmother, interloper. The judge, a woman with a jaw like an anvil, reminded counsel that nouns were not evidence. Dr. Blackwood read from the second will without flourish. Caldwell produced documents with the patience of a man building a dock in winter—board by board, cold hands, no drama. Agent Kamura testified without looking at anyone except the jury.

In the gallery, employees sat in their lunch-break best. Josephine came on her day off and glared like a guardian saint. Once, during a recess, I found her in the hallway with a paper cup of bad coffee, staring at a framed photograph of Ravensdale in 1910. “They built this town,” she said, indicating the workers—not the men who paid for the picture, but the ones standing on scaffolding, faces smudged and unwilling to smile for the camera. “They’ll build it again, if you let them.”

“I will,” I said. “Help me.”

“Always.”

In the end, Piers and Bianca were found guilty on enough counts to rearrange the rest of their lives. Xavier’s plea held. He accepted his years without protest and without looking for me in the crowd, which somehow felt like the apology neither of us could survive hearing.

The morning of sentencing, I wrote a statement and rewrote it until it walked on its own: I do not ask for punishment; I ask for proportion. I ask that the law remember the employees who lost their standing, their savings, their belief that work was a safe place to put a day. I ask that the court acknowledge harm done to a city that learned to mistrust its own reflection. And I ask that this not be the last time anyone in this room hears about Witcraft Industries because of a courtroom.

After, in the courthouse steps snowmelt, a young woman approached with a folder clutched to her chest. “My dad worked in Receiving,” she said. “He said Mr. Maxwell saved his job once. He said you saved it again.” She handed me a photograph: her father at a picnic, wearing a Witcraft softball jersey and cradling a baby who screamed at the audacity of sunshine. “For your desk,” she said.

“Thank you,” I said. “For mine, and for his.”

That night, Hion felt less like a house we had defended and more like a house that had decided to defend us back. I placed the softball photograph beside Maxwell’s journal and the roses Josephine had cut. I set the brooch back in its box because mourning and adornment are not enemies, but they are not easy friends.

At midnight, I took the key from the clock and locked the library safe, turned off the lamp, and listened to the old wood sigh. Then I climbed the stairs and slept without dreaming.

Part Four

Spring arrived with the ruthless optimism of daffodils. We held the first meeting of the Hion Foundation in what had been the blue parlor—its walls now a warmer white, its purpose shifted from showing china to choosing chances. Our board was not socialites or career donors; it was a machinist with grease under his nails who taught nighttime math at the community college; a nurse from the cardiac ward where Maxwell had not died because life had not given us the courtesy of a hospital; a high school civics teacher who looked like every kid who’d ever been told to be the bigger person and had to do it again the next day.

We funded the first round of scholarships—five children of laid-off employees heading to state universities with tuition paid and a stipend for the things financial aid forgets to name. We underwrote a compliance clinic that taught small companies how not to become big scandals. We wrote a check to a local newsroom that had lost too many reporters to layoffs and asked them to investigate us every year on our dime.

“Invite trouble?” Union Rep Morales said when I outlined the plan at Wikcraft’s quarterly meeting.

“Invite scrutiny,” I said. “Trouble arrives whether or not it’s on the calendar.”

I addressed the employees in the same auditorium where Maxwell had once announced bonuses that made grown men cry in the good way. “We will make mistakes,” I told them. “We will not hide them. We will fix belts that catch sleeves. We will change the light in the design lab so people look like themselves when they work. We will measure success in more than margin. And we will still make things that hold up to use, because that’s what this town is for.”

They applauded the way working people do: with gratitude earned that morning and likely to be tested by afternoon. It was the most honest applause I’d ever heard.

News cycles kept trying to use my life as a sermon. I let them until the volume threatened to rip the fabric, then I went to Azure Bay and let the ocean scold me for my self-importance. The soufflé fell anyway and the pianist played something cheerful by mistake and I forgave him because sometimes you must.

On a Tuesday, I received a letter in an unfamiliar legal hand: Notice of Petition to Contest Will—In re Maxwell Witcraft. Margot had filed. She claimed undue influence, mental incapacity, betrayal of corporate promises made long ago. I read it twice, then called Dr. Blackwood. “We expected this,” he said. “She is less dangerous in court than out.”

We prepared. We pulled calendars from five years ago and found in Maxwell’s precise entries the shape of a mind that did not wander. We interviewed his cardiologist and his barista and the guy at the hardware store who sold him wood glue. We retained, at Daniel’s insistence, an expert on capacity who made me read three books so I could look a judge in the eye and understand what I was assuming when I asked the court to trust our word about a dead man’s mind.

The hearing fell on a day that smelled like rain even in the courthouse. Margot arrived immaculate in taupe and truth-adjacent sympathy. Her lawyer spoke with the measured cadence of a man who believes the absence of adjectives is the presence of objectivity. He said Maxwell had been prone to romantic gestures; that his marriage to me was one long gesture; that he had been manipulated by grief at the thought of losing his children’s regard; that he had made a wild bequest in a fit of spousal devotion.

Dr. Blackwood stood, small and steady. “Maxwell knew exactly what he was doing,” he said. “He brought me the draft. He argued with me about adjectives. He tucked a joke into the boilerplate because he couldn’t resist. He signed with a steady hand. He asked me to hold it in trust until the conditions he specified were met. We have met them.”

He handed the judge an addendum Maxwell had signed two months before his death—a one-paragraph affirmation of every clause, with a postscript: If you are reading this in a courtroom because someone claims I was not myself, tell them I have loved being myself for sixty-eight years and I will not stop because they find it convenient.

The judge smiled despite herself, then built a careful, brutal bridge of law from the petition to her ruling: Denied. With prejudice. Costs to petitioner.

Margot did not look at me as the room emptied. On the sidewalk, away from microphones, she paused. “He would have forgiven me,” she said.

“He forgave you while you were doing it,” I said. “It didn’t make it right.”

She nodded once, as if I had finally spoken a line she had written for me years ago. “Take care of him,” she said, meaning the company, the foundation, the ghost that walked behind me at all hours. “He was happier with you than he ever let himself be with me.” Then she walked away into a future that would not include my name.

The day the judge dismissed the petition, the grandfather clock in the hall stopped at 3:17 as if declaring a holiday. Josephine shook her head, wound it with the tiny key, and scolded it with an affection that could bring trees into leaf. “Tick like you mean it,” she said to the clock and, by accident, to me.

At Witcraft, we cut the ribbon on a new training floor—open tables, adaptive tools, a welding bay with ventilation that didn’t leave lungs like ash. A woman named Carol lifted her safety goggles and cried while laughing. “I didn’t know it could be like this,” she said. “I thought we had to choose between fast and kind.”

“We don’t,” I said. “Not if we’re willing to be clever.”

That night, I walked the gardens and listened to the roses remind me what it costs to be beautiful at the end of a season. I felt the strange, clean ache of work that fits the bones. I sat on the back steps and wrote Maxwell a letter I did not intend to keep: We are not redeemed. We are simply pointed in a better direction. I hope that counts for something where you are.

In June, Azure Bay called asking if the foundation would sponsor a vocational scholarship for hospitality workers—dishwashers who wanted to become chefs, servers who wanted to own a café. “Yes,” I said. “With one condition: the kitchen must be kind.” The manager laughed like I had told a joke and then stopped when he realized I had not.

I testified again—this time before a state oversight committee that smelled like old varnish and disappointment. I talked about why companies break and how we pretend they don’t. I said something I had been afraid to say for months: “My husband did not die because of a bad heart. He died because he believed his children would choose decency if he made it convenient. They did not. We should stop being surprised when people take what is placed carefully within reach. Hide the candy. Lock the medicine cabinet. Count the silver. Tell the truth.”

When I finished, a woman from Accounting who had come to watch squeezed my hand in the hallway. “My mom says you sound like church,” she said. “The good kind.”

“Your mom has high standards,” I said. “Hold me to them.”

Part Five

The first anniversary of Maxwell’s death was cloudy in a way that felt designed. Josephine made his favorite stew and set an extra place at the table because she is a woman who invites the dead to eat. We drove to the cemetery with roses from the far bed—wild ones he’d insisted on planting because they refused to be mannered—and stood by the stone that did not know him. I told him about the foundation’s first year, about Carol in welding and the scholarship kid who had engineered a safer flange, about the newspaper story that had made me swear and then send money with a thank-you note.

After, I went alone to Azure Bay and asked for our table. The host recognized me and nodded without pity. The piano player kept his hands off Beethoven until dessert. I brought Maxwell’s last letter and read it one more time. Then I folded it and set it in the center of the table and imagined it traveling up through the glass and the evening and whatever separates us from what we lose.

On the way home, Caldwell called. “You’ll want to watch the local news,” he said. “There’s a pre-sentencing interview with Xavier.”

I did not want to. I watched anyway.

Xavier wore jail khaki and the hollowed look of a man who had located humility the hard way. He answered questions without embroidery. He said his father had loved him, and that he had not known how to accept a love that did not also crown him. He apologized to the employees by name—he had learned the names. He did not ask for forgiveness. When the reporter asked about me, he said, “She held the truth like a level and made me stand under it.”

I turned off the television and sat in the quiet and let the ache do what it needed to do. Then I wrote him a letter.

Xavier,

You are not a headline. Neither am I. Serve your sentence. Learn to build something that isn’t a story about yourself. When you are out, come see the Harbor Center—a building we funded downtown that insists public bathrooms can be both decent and beautiful. Push on the door with your shoulder and you’ll feel how the hinges don’t fight you. That’s design. That’s also grace.

—E. Witcraft

I did not know if he would receive it. It did not matter. Sending it was the point.

In late summer, the state auditor released a report with a cover the color of old money. It sat on my desk like a final exam. The summary used words I had come to crave: adequate, improved, compliant, verified. It also used the word culture as if we could measure it. “We can’t,” I told Dr. Blackwood when we reviewed it with the board. “But we can keep building the furniture so people sit the way we hope they will.”

He smiled. “Do you ever stop turning metaphors into carpentry?”

“Only when I’m sleeping,” I said.

We held a garden party at Hion for the employees and their families. Children ran on the lawn that had seen too many grown-up fights. The grandfather clock ticked in the foyer for anyone who came in to use the bathroom and needed a reason to look up. I gave tours of the library and did not show the safe. I placed the velvet box in a glass case with a small card: Witcraft Constellation Brooch, circa 1928. On loan from a woman who learned the sky by looking up alone.

At dusk, I stood by the rose bed and felt a presence that was not ghoulish. Maxwell would have hated the speeches and loved the potato salad. He would have told Josephine she had outdone herself and she would have told him to hush.

Union Rep Morales found me with a paper plate and a truth. “You know,” he said, “after all this, some folks still say you only have what you have because the lawyer pulled a rabbit out of a hat.”

I laughed. “Theo didn’t pull a rabbit,” I said. “Maxwell wrote a manual.”

“You going to put that manual somewhere we can find it?”

“Yes,” I said. “In policy. In practice. In people.”

He nodded. “Then we’re good.”

In September, the community clinic we funded cut its first check to a whistleblower—a soft-spoken bookkeeper who had saved a factory of jobs by telling the truth at just the right moment. She brought cookies to the ceremony and apologized for the chocolate chips melting in the late heat. “We do sticky,” I said.

When the leaves turned and the air did that honest thing it does, Dr. Blackwood called with a request that put the past to bed. “The court has authorized a public filing of Maxwell’s second will,” he said. “We can present it in open session with your statement, or quietly deposit. Your choice.”

“Open,” I said. “Let the town hear the sentence in his voice.”

The courtroom was less crowded than it had been for the trials. People get tired of other people’s mess. Dr. Blackwood read the document without drama, just the cadence of a man doing the job he chose. I stood and said, “This is not a trophy. It is a tool. We will use it to build.” Then I invited anyone who doubted to come to Witcraft on a Tuesday morning and watch Carol weld a seam that would outlast all of us.

After, in the hallway that smelled like dust and a hundred old hopes, Caldwell shook my hand, then, in a rare lapse of formality, hugged me like a brother who knows he is dismissed from duty. “We’re done,” he said. “With this part.”

“I know,” I said. “I’ll miss the versions of us who were useful.”

“You still are,” he said, and scribbled his new personal number on a card in case the world tried anything clever.

That night, I walked the halls of Hion and counted. There were twenty-three steps from the study to the foyer. Ninety seconds to wind the clock. Two hundred and six roses in bloom out back if Josephine’s ledger hadn’t lied. A house is also an abacus. I ran the beads and found I could breathe without calculating loss.

Part Six

A year and a day after the court read the will aloud, we dedicated the Harbor Center. It stood in the old rail yard where men used to count boxcars and now teenagers practiced parkour on purpose-designed ramps that doubled as seating for lunchtime concerts. The bathrooms had doors that didn’t make you cry. The faucets turned on without a fight. The center of the lobby held a table made by a local carpenter, carved from a downed oak, its surface rippling with grain like a topo map of the town’s patience.

I gave a speech that was not about me.

“This building remembers what you told it,” I said. “That you wanted to move without asking permission from every doorknob. That you wanted to see yourself in the glass without holding your breath. That you wanted to gather without calculating where to stand. You asked, and we listened, and now we expect more of every building in this town.”

The mayor cried into a handkerchief like a person who has learned to stop pretending toughness is the only virtue. Ethan—the contractor whose team had made it happen—stood with his arms crossed, eyes bright, pretending sawdust. He’d lost a wife years before and I had lost a husband and we had learned to talk without trying to sand each other smooth. We were not a romance. We were a practice: two people who liked the same verbs—build, repair, carry—and used them on the same days.

At the edge of the crowd, a young man in a navy suit lingered—mid-twenties, hair too neat, nerves making his jaw a metronome. He waited until the speeches ended. “Mrs. Witcraft?” he said. “I’m Matthew. My mother is Bianca. I… would like to work here. Not here-here,” he added, gesturing at the center. “Witcraft. I understand if—”

I looked at him and saw a boy who had grown up learning the wrong reflexes and deciding he wanted different ones. “Send a résumé,” I said. “You’ll start in Shipping on the floor Morales supervises. You’ll earn a wage and a glare. You’ll call me Mrs. Witcraft until he tells you you’ve earned Ellie.”

He swallowed. “Yes, ma’am.”

“Don’t ma’am me,” I said. “Ma’am makes me itchy.”

He laughed in relief and left with his hands in his pockets like a regular person.

That evening, we held an open house at Hion. The town came as if we had installed a porch swing across the front steps. The blue parlor hosted a small exhibit of the company’s history told with truth: how we had grown; where we had failed; who had welded the literal beams. The library offered a reading corner with books that smelled like having time. The kitchen set out sandwiches and Josephine’s ginger cake cut into squares that made men say Oh my under their breath.

In the foyer, the grandfather clock ticked, new-steadied. A boy of seven asked if he could “make it bong” and Josephine taught him how to wait until the quarter-hour. He waited like a saint and hit the lever with a reverence that would have pleased any god.

I slipped away to the study and opened the window so the lake’s breath could come in. On the desk, beneath the photograph of the softball dad and the sketchbook of me sleeping, I laid a new document. Hion Foundation—Year Two. It was less romantic than the first. More plumbing than poetry. It named things that break and who fixes them. It named who gets paid and why. It named the measure: if a worker can put a day here and take home enough to feed hope.

Dr. Blackwood arrived late, looked around the study as if counting ghosts, and then put a small package in my hand. “From an estate,” he said. “A widow who collected clocks.”

Inside: a brass key engraved with a star. “For luck,” he said. “And because your clock will stop again. They all do. The trick is to wind them before they shame you in company.”

We laughed the way people laugh when a year and a half of courtrooms and spreadsheets lets them.

Near midnight, after the last guest left and the caterers carried out the whispering trash bags and the floor regained its dignity, I sat at the bottom of the staircase and rested my hand on the banister Maxwell had smoothed with his coat sleeve because he believed wood needs touch the way people do. I closed my eyes and saw the first night he had walked me through the house with all the lights on, as if he could keep the dark from forming if he didn’t give it a corner. I saw the afternoon I had peeled off red stickers like a ritual. I saw the morning I had found the second will and the night I had decided the truth was worth being disliked for.

Josephine came and sat a step above me, knees creaking the way stairs always forgive. “You’re thinking,” she said.

“I am,” I said. “About how the title of this story makes it sound like one moment—the lawyer revealing the will—was the turning point. It wasn’t. It was one hinge among many. The door kept opening every time we decided to tell the truth and then do the work.”

She patted my shoulder. “You always had a talent for doors.”

We listened to the clock. It ticked. I imagined the pendulum swinging in a room I could see at the same time I knew it had parts I never would. That is how love is. How grief is. How houses are. How companies are. How towns are.

Before bed, I wrote one last letter. Not to Maxwell. To me.

Ellie,

The work continues. It always will. You are not finished and you are not alone. Your name on the deed, your name on the company registry, your name on the foundation letterhead—none of these make a home. Choosing, again and again, to wind the clock—that does. Choosing to call the lawyer when you have to and the florist when you can—that does. Choosing to tell the truth, even when a lie would be prettier—that does.

Tomorrow, you will read resumes for Shipping and sign a grant for the clinic and pick a paint that makes afternoon light into mercy. You will pack a sandwich for Caldwell because he forgets to eat and call Kamura on her birthday because she won’t. You will order bulbs for the far bed and remember to sit while the kettle boils. You will look at the brooch and decide not to wear it because your sweater is enough. You will listen to the clock and think, This is not a countdown. This is a metronome. We are making music.

Wind it.

—E

I propped the letter where future-me would trip over it and smiled at the impoliteness of my own hope. I climbed the stairs, touching the banister as I went. In the bedroom—the one that had learned both absence and the sound of a person sleeping without apology—I turned down the covers and laid my palm on the empty side of the bed.

“Goodnight, my heart,” I said into the dark, because saying it still made the air feel like a room with windows. Then I slept.

In the morning, the clock struck six in a voice that had known other houses, other hands. I dressed. I walked downstairs. I wound it.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night

When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night Part One…

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement Part One I never…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then… …

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead Part I — The Test Shot…

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything Part 1: The…

They Begged Me to Pay for Surgery—Then I Found the Sports Car Receipt.

They Begged Me to Pay for Surgery—Then I Found the Sports Car Receipt Part One The call came at…

End of content

No more pages to load