After my dad’s funeral, my SIL suddenly said the inheritance goes to her husband. I was stunned…

Part One

I’m Meline. I’m twenty‑nine years old, and I have worked at my father’s company for a decade—first as a timid high‑school graduate filing invoices, then as an operations coordinator, and, lately, as the person people come to when something breaks. My father, Gérard, built the company from nothing. He started with a borrowed truck and a rolling cart when I was four; he and my mother ran deliveries and did books at the kitchen table by lamplight because the electricity bill didn’t always cooperate. By the time I turned eighteen, he was employing fifty people, and the rolling carts had become a proper logistics floor with color‑coded lanes.

When I close my eyes, I can still see my father the way I like to remember him: rolled‑up sleeves, grease under his nails, calculating route efficiencies on a paper napkin while eating a sandwich standing up so he could get back to the floor. He was not the kind of owner who hid in an office. He was the kind of owner who kept spare work boots for new hires in his trunk and said “we,” not “you.”

People love to romanticize a founder, but there were years when his success was less romance and more survival. I remember whispered conversations about bank covenants and the cold press of dread in the house when a client paid late. Even after we were comfortable, I never stopped noticing how intimately money knew our family.

College was on the table for me, but it felt all wrong to sit in lecture halls while my mother answered vendors with a frazzled smile and my father tried to make payroll stretch. I told my parents I wanted to work for the company. Mom tried to push me toward “what you love,” and I told her that this company was that. At seventeen, I didn’t know all the ways that was true and all the ways it would become more complicated later. I only knew that when I walked the floor and the forklift beeped and an order went out perfectly packed and labeled, something in me clicked into place.

My father didn’t make it easier because I was his daughter—if anything, he made it harder to teach me how to stand. “Anyone can hold a title,” he used to say, showing me how to read order flows. “Not everyone can earn a team.” When he wasn’t teaching me, he assigned someone who would: Wilson, a veteran who had been with the company since we could count orders on two hands.

Wilson is the kind of man who can do math in his head and make coffee you want to drink. He never looked at me through the lens of “the boss’s daughter.” He told me when I mislabeled a pallet and sent it to Hawai‘i instead of Hazlet, then showed me how to fix it without drama. He taught me to ask better questions. He also taught me that praise means nothing if you don’t share it down the line. When I made a good catch, he would say, “Tell the packers they saved the day; I’ll buy the donuts.”

“I’m learning,” I told my father one night, exhausted and exhilarated after a redesign of our picking lanes shaved twenty seconds off every order. He kissed my forehead and said, “Good. Don’t ever stop.”

My brother, Cooper, is two years older than me. He went to college to study “business,” which for him turned out to mean calling Dad and asking for money in a lower baritone. He loved the spotlight and would claim at parties that he was “going to inherit the company someday.” He didn’t hide his pronouncements; he tried them on like suits in front of his friends.

“Cooper, what’ll you do after graduation?” someone asked him once at a barbecue while their beer sweated rings on our picnic table.

“I don’t need to job hunt,” he said, tossing his hair. “I’ll join Dad’s company. It’s already decided I’ll be the president one day. Until then I’ll get experience as a manager.”

“Isn’t Meline working there, too?” another friend asked. “Won’t there be a rivalry for the chair?”

Cooper snorted. “Meline? She’s a high‑school grad doing behind‑the‑scenes busywork. If I become president, I’ll… let her keep her role. If she does what I tell her to do.”

He said it like a joke. It didn’t feel like one.

Under the guise of “gaining experience as a manager,” he spent lavishly. He made “connections” by taking people out for dinners that cost what we used to spend on school clothes in a year. Maybe he liked that those connections came with clapping and other people calling him “sir.” Women flocked to the lifestyle he performed; they called him “future president” and meant it. He picked the flashiest one and married her because he could. Her name is Lucy.

Their wedding had a string quartet and an ice sculpture and a flower arch that smelled like debt. They honeymooned in the Maldives for three weeks and posted photos with captions like “a president needs his rest.” They built a mansion on a hill with a view of the river, because when you are building a persona, height helps. Lucy glided through all of it like she was born at a gala. She loved silk robes and saying “our driver” and telling me, when we ran into each other in the break room at Dad’s office, “You really don’t seem like the president’s daughter. So plain.”

“I’m not fond of a flashy lifestyle,” I said once, setting a stack of file folders on a desk.

“Poor you,” Lucy sang, and peered at her manicure. “Born into wealth and don’t know how to use it. Living with your parents with plenty of money… there’s no need for you to work hard.” She glanced at Cooper and they both laughed. “With the title of president’s daughter, men will flock to you. If not, I can loan you one.”

Cooper smirked at me over Lucy’s shoulder. “Meline’s always been plain. She treats employees like equals. That’s not how a president acts. The president has to command respect. Let others handle mundane tasks.”

“You don’t command respect by acting superior,” I tried to reply. “You—”

“Enough already!” Cooper waved a hand. “No one likes a nitpicking woman. If I become president and you still insist on being stubborn, I might have to fire you.”

Our mother overheard all of it and squeezed my hand when they left. “He’ll learn,” she whispered. “You aren’t wrong.”

“He should already know,” I whispered back.

My parents tried to confront him about his attitude once; it ended with him and Lucy icing us for a month. After that, we decided not to chase them. They continued living like Instagram proxies for success—fine restaurants, famous resorts, cars that sounded like apologies for something we couldn’t name. Dad went to the office every day, tie crooked, coffee in hand, building new routes and signing contracts and saying “we” and meaning it.

Then, one night at home, he clutched his chest at the sink.

“Dad, are you okay? Hang in there!” I cried, and my mother’s voice was rising to a pitch I had only heard once before when I fell and split my chin on the steps. He was gray; his lips looked like paper. “Meline,” he rasped, pushing a hand at his desk. “Take this.”

He looked at me with a focus that pinned me in place. “If anything happens to me, read this,” he said, indicating a drawer. “Everything else is with the lawyer.”

The ambulance took too long and too fast and he left us in a rush that felt like a door blown open by wind.

Cooper and Lucy were in Bora Bora. They didn’t make it home in time. They arrived two days later in white linen, smelling like salt and expensive soap. They stood over his casket and said the right things in the wrong voices. They left my mother and me to plan the funeral and then announced that the food wasn’t “presidential.”

“Couldn’t you have flown back sooner?” I asked quietly, out of earshot of employees who had taken off work to pay respects.

“The return flight was set,” Cooper said, shrugging. “Couldn’t change it—penalty fees.” Then he turned with a practiced smile to a line of mourners. “Thank you all for supporting my father. I’ll take over and lead from here, so trust me.”

They stared at him. He mistook it for awe.

Lucy fanned herself. “See, Cooper? Too moved to speak. Of course they’re impressed. My husband commands respect.” She pointed at the buffet. “Meline, where is the memorial meal? Show us already.”

We ate. People told stories—Wilson cracked a joke about Dad’s coffee in the early days that made Mom laugh and then cry, and he passed her tissues. Cooper criticized the food anyway. “Low‑grade,” he muttered. “Ruins Dad’s dignity.”

“You weren’t there to choose it,” I said quietly. “Don’t criticize what you didn’t help with.”

He snorted. “This is why you don’t understand presidency.”

He started ordering employees around. “You, pour me a beer. Not like that—are you useless?” He tried it with Wilson. Wilson lifted his eyebrows and took the pitcher from him slowly, calmly, like taking a toy from a child.

“Cooper,” I said, stepping in. “Don’t disrespect Mr. Wilson.”

“It’s them being disrespectful,” he shot back. “I shouldn’t have to humble myself before employees. They should show me respect.” Lucy pursed her lips and leaned in, sharp as a knife. “Meline, don’t speak to President Cooper like that. Keep it up, and we’ll fire you.”

I didn’t have time to answer. The lawyer arrived.

“Sorry to interrupt,” he said, a neat man with a black folder and a face practiced in solemnity. “I’m handling the inheritance proceedings for your father.”

My stomach dropped. Dad had told me: Everything else is with the lawyer. He had planned for this moment—the one where grief meets paperwork and manners.

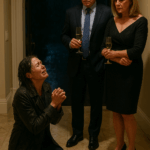

Cooper and Lucy’s eyes lit like slot machines.

“Thank you for coming,” Cooper said, voice dropping into what he thought was his executive register. “It’s best to get this sorted quickly.”

“Isn’t the inheritance three million?” Lucy blurted, delight cracking through the façade. “Three million? It’s like a dream to have both the inheritance and the company.”

Employees, clustered in the reception room, began whispering. Lucy turned, smiling like a campaign poster. “Quiet, please! This is an important moment when my husband inherits three million and the company.”

Someone couldn’t help it; a snort escaped—then a short burst of laughter.

Lucy whipped around. “What’s so funny?” she demanded.

The lawyer opened his folder and extended a single document. “There’s a will,” he said. “Your father made it several years ago. It is valid and current.”

Cooper took it. The paper shook in his hand. His eyes skimmed the first line, then went back, then froze in a way that told me he had reached the line Dad had planned for.

His face drained. He made a sound like a man swallowing a rock. “This… this can’t be,” he stammered. His eyes flicked to me, then to Mom, then to the employees, still as stones.

Lucy snatched the paper. She read, and every drop of blood left her face. She screeched—an ugly, high sound that made an aunt jump. “What? No. No!”

People looked at me.

I had a letter too—the one from Dad’s desk at home, the one he’d pressed into my hands with a grip so fierce it left nail moons. He had told me in that letter everything he had done for Cooper over the years, counted as “living gifts”—money for the house, the cars, the trips, the parties. Every bauble Lucy had giggled over had been accounted for. He had made sure the ledger would be balanced even if his hand wasn’t there to hold the pen.

The lawyer cleared his throat. “Per Mr. Gérard’s will,” he read, “the entirety of the company is bequeathed to his eldest daughter, Meline.”

It was like someone had shaken the room. Cooper wobbled; Lucy made a strangled sound. The employees didn’t move. The one who had laughed earlier pressed his lips together so hard they whitened.

“No,” Cooper said, voice rising. “No. Dad was senile. He must have been confused. This is absurd. A will written by a senile old man is invalid!”

The lawyer didn’t flinch. “Your father set up this will six years ago, with witnesses and mental‑capacity affirmation by his doctor. It has been updated for assets but not materially changed. It is valid.”

Cooper slammed the paper down. “Who cares? I’m the son. Everyone knows the son takes over.” He spun to the employees. “Are you all okay with this? With a dull woman like Meline running the company? I have Dad’s charisma. I’m more suited to be president!”

No one nodded. An uncomfortable cough came from the hallway. Wilson stepped forward—smaller than Cooper but somehow taller in that moment.

“Your father had charisma,” Wilson said quietly. “He also had humility. He built this place. The difference between you and him is like night and day.”

“What did you say?” Cooper’s voice tilted toward a shout.

“What you have isn’t charisma,” Wilson said, his tone steady. “It’s arrogance. You look down on us. You don’t know our work. Technically you’re on the roster, but we’ve hardly seen you work. You say you’ve been building connections, but most nights that looks like bars and vacations. That may be ‘connections,’ but it’s not leadership.”

“And what would you know?” Cooper sneered. “Packing boxes is not presidency.”

Wilson’s mouth twitched—not a smile, not pity. “I know your sister shows up. She listens. She learns. She shares credit. We feel the same sincerity in her that we felt in your father. Many of us believe she is fit to be our president.”

It wasn’t loud, the noise that came then—more like the sound of air leaving a room in relief—but I felt it. No one had to shout agreement; a dozen small gestures said enough: a hand on a shoulder, a nod, a straightened back.

My throat was tight. “Thank you,” I said to the room, voice rough, heart pounding against my ribs. “I know this is sudden. I know grief is still heavy. But you all taught me this company matters more than any one person. I care about it as much as you do. Please continue to work with me. I promise to earn your trust every day.”

Warm applause followed—soft, insistent, real. Lucy looked confused, as if applause was something she thought you bought.

I turned to Cooper. My hands were steady. “All these employees have supported this company. Anyone who neglects them doesn’t deserve to be president, nor an employee. You told me once you’d fire me. Now I’m telling you the opposite. Cooper, you’re fired.”

He blinked. “What? I’m your brother.”

“You said it yourself. You’d fire family. I can’t pay someone who has never contributed.”

He turned in a circle, looking for someone to save him. The employees studied the carpet. He grabbed Lucy’s arm. She yanked it back. “Do something,” he hissed.

Lucy was calculating something—a column of numbers had shifted in her head and she didn’t like the result. “But the three million,” she sputtered. “We couldn’t have spent all that. That’s in the inheritance, right? Where’s the money?”

The employee who had laughed earlier snorted again, this time without apology. He stepped forward. “Everyone here knows that ‘three million’ is the company’s operating funds, not personal savings to be distributed like party favors.”

I held up Dad’s letter. “The company’s money is not subject to family inheritance. It belongs to the company. Dad’s personal estate is separate. And Cooper, your living gifts are already accounted for.” I tucked the letter away. “I’m sorry, Lucy. You’ll find that your share is far smaller than you imagined. Debts weigh more than dreams.”

Lucy stared at me. Cooper made a strangled noise and knocked a chair with his knee. He looked around at the employees. No eyes met his. The silence was an answer.

He fled. Lucy followed, her heels clicking their own small, angry language across the tile.

I took a breath so deep my ribs hurt. I glanced up at the ceiling and imagined Dad grinning somewhere, elbowing someone and saying, “That’s my girl.”

I bowed to the room. We had a mountain of work to do, and we would start in the morning.

Part Two

Grief didn’t pause for the work, and the work didn’t pause for grief. That week, we put together a transition team. The lawyer held my hand through technicalities: notifying the bank, updating the board registers, informing clients so rumors didn’t do their usual violence. I spent two days visiting key vendors, sat with the union reps for two hours in a cramped office under a fan that didn’t oscillate, and walked the floor with Wilson until my feet throbbed. Everyone wanted to tell me how much they had loved my father; I let them because it stitched me together.

In the quiet of my new office—the same office Dad had resisted occupying until Mom insisted he deserved a door that closed—I wrote a memo. It wasn’t poetry. It was simple, specific, and mine: my commitment to transparency; my expectation that we greet mistakes like opportunities, not weapons; my promise that I would never ask them to do something I wouldn’t do; my insistence on respect, up and down the line. I signed it and pinned it to the bulletin board in the break room.

I didn’t sleep much. I drank too much coffee. My mother sat with me at night and told me stories about the year Dad took apart a toaster to understand why it failed, then rebuilt it and mailed it to the manufacturer with a letter that started, “I love your product, but—” We cried and laughed and then cried again.

On the third day, a board member called to tell me a vendor had received a call from someone claiming to still be president.

“Cooper,” I said, and thanked the man for the heads‑up. He sounded embarrassed for me. I was beyond embarrassment. I called my lawyer and she called theirs and that was the end of that.

Cooper tried to enter the building once. Security called me. He stood in the lobby with Lucy, sunglasses on, like a person who thinks not seeing a thing means the thing is gone.

“I need to speak to my team,” he said.

“This is not your team,” I said. “You’re not welcome here.”

He puffed up. “You’re a girl playing dress‑up. You can’t fire me.”

“Watch me,” I said, and watched the security guard escort him out. Lucy muttered something under her breath that sounded like “You’ll be sorry,” the kind of threat people make when they mean “I don’t know what to do.”

They stopped calling after that. I imagine the lawyers told them how foolish it would be. Or maybe shame finally found them.

News of the will and the firing spread faster than I would have liked. People came out of the woodwork to see if the rumor was true. Some came to gloat. Some came to offer advice no one asked for. A few came to sincerely offer help. A former client called to say, “We always dealt with your father because he kept his word. If you’re the same, we will be too.” I said, “Hold me to it.”

A reporter left two messages asking for comment about “the scandal.” I didn’t return them. This is what I’ve learned: you don’t owe anyone your feelings to prove you have them.

We held a town‑hall in the warehouse the following week. I stood on a pallet like my father had done when he couldn’t resist a pep talk, and I told the truth. I didn’t pretend mourning wasn’t a second job. I didn’t promise miracles. I promised we would show up for each other. I asked for patience and gave it in return.

An older man at the back—one of our drivers—raised his hand and said, “Your father would be proud.” I nodded. That’s all I could do without crying.

We outsourced what we weren’t good at. We brought payroll in‑house after an outside provider messed up a holiday differential. We negotiated with a landlord and shaved $1,400 from a lease. We remapped a picking route—Wilson and a twenty‑two‑year‑old new hire with a piercing who knew more about software than anyone else—and shaved another twenty seconds off each order. Small efficiencies add up like rain.

I took my mother to lunch on a Tuesday to celebrate nothing in particular and told her I’d decided to set up a scholarship in Dad’s name: one work‑study a year for a logistics student, paid summer at our company, with a promise to hire if they fit. She cried into her soup. “He’d like that,” she said.

It wasn’t all heartwarming. One morning, the credit card machine failed and a truck needed loading and the printer jammed and a client called to say they’d found a half‑eaten granola bar in a shipment—“we’re a nuts‑free facility,” the woman said gently, and I wanted to sink to the floor and apologize for the rest of my life. Instead, I apologized, offered a discount, sent an email reminding people to keep food out of the packing area, and bought bigger signs. Failure isn’t proof you can’t; it’s proof there’s more to do.

A month later, I received a text from a number I didn’t recognize at first. It was Cooper. He wanted to borrow money.

“Lend me some money,” he wrote. No greeting, no apology. Just a sentence he had written a thousand times in his head and assumed would always work.

“No,” I wrote back, and blocked the number.

The next time I heard about him, he was working nights at a convenience store. A friend sent me a photo accidentally when they checked in at the gas station—I recognized the slump of his shoulders, the way his hands looked too clean for the work. I didn’t show the photo to my mother. Lucy got a job as a cashier at a supermarket and stood in a line with women she had once mocked—small lives, she’d called them—ringing up bread and cigarettes and bags of onions in a uniform that made her look like everyone else. I wish I could say I felt triumphant. Mostly, I felt tired. Consequences aren’t triumph; they’re gravity.

We sold their mansion. The house had been on the market with glossy photos that made the river look like their property. It wasn’t. When it finally closed, they relaxed just long enough to spend more than they meant to and realized the money wasn’t infinite. It was never infinite; it just felt that way when someone else paid the bills.

By the time Cooper decided to “get serious” about a job, the market had moved on without him. He had charisma, he told people. “We don’t need that,” they told him. “We need someone who can show up and not scare people.”

He did eventually find a job as a clerk. The ironies of life have mercies in them: the manager was three years younger than me and had never heard of my father or our company. She taught Cooper how to count cigarettes and balance a till. He complained. She didn’t listen.

Lucy borrowed from her parents to pay compensation in a lawsuit she had insisted was “nothing” until it wasn’t. She moved in with a cousin. Her Instagram turned into photos of coffee cups and sunsets without captions—not a metaphor, just retreat.

You might expect a confrontation—some dramatic apology in the rain. It didn’t arrive. Real life is quieter. It turned out the worst thing I could give them was silence and the second worst was a door that closed when they tried to walk back through it.

One afternoon, months after the funeral, Cooper came to the office. He wore a collared shirt and practiced his smile in the glass before stepping in. He didn’t see me at first. He looked around and seemed confused that people were working without him.

“I want to speak to the president,” he told the receptionist.

“You are,” I said, coming around the corner. “She’s busy.”

“Five minutes,” he begged. He added, “Please,” like it hurt.

“Three,” I said, and took him into a small conference room that still had my father’s handwriting on the whiteboard from a meeting about “pallet flow improvement.”

He sat. He didn’t pose. He didn’t sneer. He looked… human.

“I didn’t know it would be like this,” he said, staring at his hands.

“Like what?”

“Hard,” he said, sounding stunned. “It’s all hard.”

I kept my voice even. “Work is hard. So is respect. So is honesty.”

“I’m not asking for money,” he said, too quickly. “I’m asking for… advice.”

It was the first thing he’d asked me for that didn’t cost something I needed. For a second, I saw him at fourteen, lanky and impatient, tugging at Dad’s sleeve to show him a science project that didn’t work big but worked in him. I took a breath.

“Show up,” I said. “Don’t pretend. Learn to do one thing well and then another. Tell the truth. Don’t take what isn’t yours. Thank people. Eat crow. Keep showing up.”

He laughed without humor. “That’s all?”

“That’s everything,” I said.

He nodded. “I’ll try.”

He left without asking for money. I put my forehead on the cold glass of the conference room door and cried a little anyway because letting go is hard even when it’s the right thing.

When Dad’s birthday came, we held a small memorial in the warehouse, coffee and cake and bad jokes. Mom told the story about Dad taking apart the toaster again. Wilson presented a plaque: “In memory of Gérard, who built more than walls.” We clapped and someone sniffed and a forklift beeped twice and I felt, for the first time since he died, something like joy fold itself carefully into grief and make room for both.

“Promise me two things,” I told Mom later, sitting on the loading dock after everyone went home, feet swinging to the rhythm of a song I couldn’t hear. “Don’t give Cooper money. And don’t let me turn into a person who thinks applause is the point.”

She squeezed my knee. “I won’t,” she said. “To both.”

We grew. Slowly. On purpose. We hired two apprentices from a work‑study program and watched them teach us things we hadn’t known we didn’t know. We started a scholarship in Dad’s name. We added health coverage to part‑timers. We failed small and learned big.

I kept Dad’s letter in the top drawer of my desk, folded, the crease softening with time. I didn’t need it anymore to know where the lines were. But sometimes I read it when I wanted to hear his voice say one last time, “Everything else is with the lawyer,” and feel the weight of a handoff done well.

On a Friday in late spring, the sun slanted through the warehouse windows and made dust look holy. The team surprised me with a cake for my first year as president. It was lopsided and perfect. Someone had written “We TRUST you” in sloppy blue icing. My mother took a photo of me holding a knife above the frosting, laughing with my head thrown back, the way I hadn’t done in years. Wilson stood behind me, clapping off‑beat like he always did, and said, “Donuts on me Monday.”

“Thank you,” I told them. “Thank you for staying. For doing the work. For doing it together.” My voice was steady. “Let’s make my father proud because we are proud of ourselves.”

On the drive home, the river looked like it always had. The mansion on the hill caught the last light and looked beautiful in a way that had nothing to do with the people who had once lived in it. I stopped at a red light and checked my phone. A message from a client: “Heard about your dad. He was a good man. You seem to be one too.” I grinned. I didn’t correct the grammar.

When I reached our cul‑de‑sac, I parked and sat for a minute, engine off. The night bugs started their work. A kid on a skateboard clattered past, dragging one foot—the happy sound of someone going nowhere important. I went inside and placed my keys in the little dish Dad had made in a ceramics class as a joke. It was crooked and lovely.

Standing alone in my kitchen, I whispered to the ceiling like a fool: “We’re okay.”

Through the window, between the potted basil and the ridiculous flamingo Mom insisted I needed in the garden, the warehouse lights glowed far off, a ribbon of gold along the road. I thought about the employees—my colleagues—wiping cake off their hands with paper towels, rinsing mugs, turning off switches, leaving together.

I vowed, as I had vowed at the funeral under the hard fluorescent lights that made grief look sallow: I will grow this company alongside my mother, not because I inherited a title but because I inherited a team. I will make the work honorable. I will not become the thing my brother thought a president was. I will ask for grace when I fail. I will earn this.

Somewhere, if there is somewhere, I hoped my father was laughing that horrible coffee laugh, slapping someone on the back and saying he’d bet every cent and every sleep‑deprived night that his plain, behind‑the‑scenes daughter would do it right. He would have lifted a mug and said, “to Meline,” and told me to get my hands out of my pockets and back to work.

So I did.

And as for Cooper and Lucy—whether they found their way or didn’t, whether they learned soft or hard—I wished them exactly what they deserved. Not my pity. Not my rage. Only a life without borrowed lights, where the only brightness they could rely on was the kind they made with their own hands.

END!

News

My ex-husband’s mother told me to leave ASAP when I got a divorce, but she regretted it later… CH2

My ex-husband’s mother told me to leave ASAP when I got a divorce, but she regretted it later… Part One…

My husband and daughter ignored me forever, so i left in silence. Then they started panicking… CH2

My husband and daughter ignored me forever, so I left in silence. Then they started panicking… Part One My name…

My husband: “You’re nothing without us!” My exit left them aghast and speechless! CH2

My husband: “You’re nothing without us!” My exit left them aghast and speechless! Part One The room was filled with…

My MIL Coveted My $12,000 Watch and Staged a Deceitful Swindle. She Nearly Got Away with It Until…CH2

My MIL Coveted My $12,000 Watch and Staged a Deceitful Swindle. She Nearly Got Away with It Until… Part One…

Mom Changed the Locks, Sister ‘Earned’ the House — Lights Went Out, I Said ‘Ask the Owner’. CH2

Mom Changed the Locks, Sister “Earned” the House — Lights Went Out, I Said “Ask the Owner” Part One The…

My Brother Moved In ‘For Two Weeks’ and Ate Six Months of Bills. CH2

Part One Two weeks, Jerry said, engine noise hissing under his words, just to land on my feet. My name…

End of content

No more pages to load