After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner

Part 1

I don’t remember the instant the car lost the road—only the screaming skid and the way metal made a terrible, intimate sound when it folded. Something hard kissed my forehead. The world went black, then gray, then a mean little tunnel with smoke curling out of my hood and the night air cutting my lungs as if it were edged.

I crawled. My left leg wouldn’t answer when I asked it to hold me, so I dragged it behind me the way a child drags a too-heavy suitcase. Gravel bit my palms until they slicked. Every push forward was a ledger line of pain. A porch light glowed ahead—the same front steps I’d run up as a kid after swimming practice, after late buses, after heartbreaks I thought would kill me and didn’t.

I made it to the door and collapsed. Blood pounded in my ears. I reached for the handle and missed. “Mom,” I whispered. “Dad.” I tried again. “Help me.”

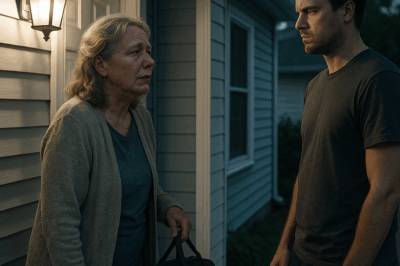

The door swung open on a blast of warm air that smelled like roast and perfume. My father in a pressed shirt, collar just so. My mother with a glittering necklace and a practiced smile. For one animal, shining second, I thought: home.

Then he stepped over me like I was a bag left in the hall. “Don’t bleed on the rug,” he muttered, an old complaint fitted to a new horror. My mother’s heels clicked past my ear. She looked down and curled her lip.

“Pathetic,” she said, laughter under the word like glass under a shoe. “Crawling like a stray mutt. Dinner reservations are waiting.”

I reached for her wrist without thinking—instinct, not strategy. She yanked back with a hiss. “Don’t touch me. You’ll ruin my dress.”

Something in me broke loud enough to hear. “Please,” I said. “Something’s wrong.”

Dad bent at the waist, his breath hot and soured. “You’re always broken,” he said softly, the way someone tells you the weather. “Tonight at least, you’re out of the way.”

They stepped over me. The door shut. The lock turned. Through the front window I saw them laugh as they crossed the walk—two figures perfectly cast in the roles they loved: poised, entertained, on time. My sister swanned up from the driveway, brandishing her phone, snapping a picture of the three of them, the night, the car—a tableau as glossy as a magazine ad.

The engine roared. Their taillights smeared the street red.

The porch ceiling looked the way it always had, rows of beadboard painted the color of resignation. I lay there and learned a truth I had dodged for years: it wasn’t that they didn’t love me well; it was that my being erased made their lives easier. This knowledge did not make me noble. It made me cold.

I rolled onto my stomach. If they could lock a door on me, I could unlock a different one. I dragged myself back down the steps, fingers leaving pale crescents on the risers, then onto the street where my car hunched like a wounded thing. I crawled until headlights spilled around a curve. A stranger braked hard and ran. “Oh my God,” he said, words that actually meant something. He called an ambulance. He put his coat under my head. He kept saying I was okay even though we both knew we were guessing.

The hospital was lights and voices and a needle so smooth I almost cried from the relief. They wired my jaw. They wrapped my ribs. They slid my leg into a brace and said don’t be a hero like that was an option. I stared at the ceiling tiles and replayed my mother’s laugh, my father’s line—tonight at least, you’re out of the way—until it lost grammar and became a noise.

They didn’t visit. Of course they didn’t. Three days in, my phone buzzed with a text from my mother: Stop milking it. You’re alive. Be grateful. My father didn’t bother. My sister’s posts bloomed with filtered pictures of cocktails and jokes captioned family first.

The discharge nurse checked my chart and looked for the name of the person who’d pick me up. Her eyes moved over the blank. She didn’t pity me. She looked practical. “Do you have cash for a cab?” she asked.

“I do,” I said, and my voice sounded like it belonged to a person who would always have just enough.

Back at my little rented place, I learned the logistics of pain. Pill timers, ice in tea towels, how to sleep with a ribcage that complains. I learned how long it takes to change your own sheets with a leg that has decided democracy is optional. Nights were long. Pain meds fuzzed the edges and gave me time to think. Recovery, I realized, wasn’t only about bones. It was about armor—the kind that goes invisible and lives under your skin.

If they could walk away from me like I was an inconvenience, then one day they would walk back and find there was nothing for them to stand on. I didn’t mean it as a threat. I meant it as a promise to myself: never again would I make my survival contingent on their mood.

I made lists the way other people pray. PT at 10; call insurance; research debt pulls. Once the worst of the pain dimmed to a shout I could ignore, I started walking farther than the kitchen. Walker to crutches to cane. Each step reclaimed a square foot of land in a country I intended to govern.

I thought about what they valued. Not me. Not my stupid persistence. They valued shine: my mother’s jewelry and her fussed-over dinners, her reputation for tasteful charity and tastefully withheld gossip. My father’s business—the clean handshake, the Sunday-school smile, the little nods he collected like stamps. People called him a pillar. Pillars are useful when a building needs them and heavy when it doesn’t.

I dug. Public records are surprisingly generous if you’re patient. Unpaid invoices. Lawsuits other people had quietly dropped because my father had convinced them he’d make it right later. A business loan that had my name on it—a signature I didn’t remember giving my hand to. A department-store card opened when I was nineteen, maxed, late fees piling like snow. My sister’s vacation photos tagged with items that had been bought on accounts that fed those fees.

I printed everything. I stapled and highlighted and labeled. Not because I planned to run to the police and hand them my life, begging them to fix it; I was done handing my life to anyone. I needed leverage and a spine of paper.

By day I did my job with a vigor that would have looked like ambition to someone who didn’t know why I was working so hard. I said yes to projects and learned to read contracts—the same way you learn to read a room. By night I did my exercises and learned to silence my phone. I let people assume I was fine, or not fine, or whatever made their day easier. Being underestimated, I discovered, is camouflage.

The first time I saw them again was at a charity gala I wasn’t invited to. I wore a rented dress the color of a bruised plum and stood in the back like a volunteer who’d lost her clipboard. My parents sparkled near the stage, laughing with people they needed to laugh with. My mother turned so the light fell perfectly on her necklace. My father clapped one beat early before every speech so everyone could see his enthusiasm arrive first. My sister showed everyone a ring and pretended to be surprised every time someone gasped.

“Isn’t that their other daughter?” someone whispered near me. “The one they never mention?”

I felt the words like a particle of heat. I smiled the kind of smile you give a stranger who hasn’t realized the thing they just found is a match.

I left before they could notice me. It wasn’t time. Timing is a tool. I had learned that while counting my steps from the bed to the bathroom and back again.

I started to catalog their rituals the way a hunter learns a pattern. What night the “standing reservation” existed for. When he gave talks at church about family values and the importance of showing up for your children. When she posted a story about the sacrifices mothers make. I swallowed the urge to comment. I let them write a script for an audience that believed them. Then I chose my stage.

Christmas. Their party was a town tradition—tree like a wedding cake, a buffet that made people say oh you shouldn’t have while going back for more, the guest list sprinkled with the names they liked hearing themselves say. It was their favorite mirror. I would hold it up.

I built a packet that would shame a prosecutor for not making a case: bank statements, credit pulls, scans of signatures side-by-side with the one they taught me to write in second grade. Screenshots of my mother’s text and my father’s silence. A photo of me in the hospital two days after the crash, jaw wired shut, bruises making a map across my chest, while their location tags bloomed from a steakhouse downtown. And because some people only believe what they can hear, a recording: their voices at the door, captured by the camera I’d forgotten my landlord had installed above the porch light years ago.

I slid each piece into an envelope I could have addressed in my sleep. I circled a date in red. I put the plan down and let it harden.

I didn’t expect fear to vanish. Fear is part of the body’s wiring, and I’d had wires threaded through me for the better part of a month. But by the time the house lit itself up in a hundred warm squares and I stood at the edge of the drive with breath fogging the dark, fear was a quieter voice.

I walked through the front door the way a person walks into their own kitchen. The room paused. Then it adjusted around me like I was furniture that had always been there. My father boomed laughter at the fireplace. My mother twirled to show someone the emerald at her throat. My sister extended her hand and gasped a little sound that was supposed to mean bliss.

I cleared my throat. It’s a small sound. It went everywhere.

Heads turned. Her smile froze first. Then his. My sister’s mouth formed what’s she doing here the way some people mouth along to a favorite song.

“Merry Christmas,” I said, and laid the envelope on the grand piano like an offering and a threat.

Dad started talking—he always starts talking. “We didn’t expect you,” he said, puffing himself up. “This is a private—”

“Oh, I know you didn’t expect me,” I said. “You didn’t expect me when I crawled to your door with broken ribs either. You stepped over me then. But tonight I’m standing.”

Silence can be loud. The room went loud.

I opened the envelope and fed paper to the light. Bank statements. Forged forms. Screenshots. A release sheet with my name and the date and a nurse’s note that read patient discharged to self-care—no family present. A photo of my face swollen where it shouldn’t be. I laid each page like a card.

People made the little noises decent people make when they see indecent things. “Good God,” someone said, and I forgave the echo of my porch rescuer in his voice.

My mother leaned in, smile tight as a seam. “Stop this,” she hissed. “You’ll ruin everything.”

“That’s the point,” I whispered back.

My father reached for the papers with a hand that had signed my name so convincingly. A guest got there first and read, out loud. Words are heavier when they’re not yours. His voice cracked, then steadied. I saw the moment he refiled my father in his head from pillar to something else.

“She’s lying,” my sister said, because sometimes a script is all you have.

I took out my phone and pressed play. The house speakers weren’t mine. The sound was. My mother’s laugh; my father’s line—you’re always broken—played back to them in their favorite room. People gasped and cursed and stepped back the way you step back from a snake you didn’t see in the grass. A business partner put down his glass and walked out. My mother’s friend tossed wine into the dress she had bragged about. The priest from their church shook his head, more tired than mad, and left.

By the time I closed my bag, the party had let itself out. The house looked exactly the same—lights right where they’d been placed, ribbon still curled, the tree not embarrassed at all. The ruin wasn’t in the decorations. It was in their faces.

“Please,” my father said, and I had never heard that sound come from him. Pride gone, voice smaller than mine. “Don’t—”

“You’ll ruin us,” my mother said, hands shaking like she’d finally learned she owns them.

“You ruined yourselves,” I said. “I turned the lights on.”

I walked out. The winter air hit my face sharp and clean. Somewhere behind me, someone fumbled with the papers, as if reordering them would reorder what had happened. The driveway glittered with ice. I didn’t slip. For the first time since the crash, I wasn’t crawling.

Part 2

They didn’t call the next day. They called the next week, when the fallout started to have shape. Reputation is a fabric; pull in one place and the whole thing puckers. Clients postponed meetings. The charity board asked my mother to “take a restorative pause.” The church committee discovered a scheduling conflict that would last six months. I learned all this the way one learns the weather—neighbors chatting on porches, a cashier who’d seen the video on someone’s phone. People always say I don’t take sides as they angle their bodies to make clear which side they’re on.

When my father finally did call, his voice had the crackle of a call made from a car, from a man moving. “You made a scene,” he said, as if that were the crime.

“I made a record,” I said. “The difference is important.”

“You don’t understand business,” he said, then pivoted without a breath. “Your mother hasn’t slept.”

“I did,” I said. “For the first time in months.”

“Do you want money?” he demanded, as if it were a system reboot.

“I have mine,” I said. “What I want is simple: my name off everything you put it on. Every account. Every card. Every loan. You will clean it, and you will send me the paper that says it’s clean. If you don’t, I file what I haven’t filed yet.”

He cursed. Then he tried on a softer voice that felt used. “You know we love—”

“Don’t,” I said. “Say you when you mean we. Say action when you’re about to say feeling. You’ll find it clarifying.”

He hung up on the sound of his own breath. I wrote the date and time in a notebook that had become a ledger of my life.

I did not wait for them to do the right thing. Waiting is a kind of prayer, and I had lost my religion. I went to a credit counselor who wore a sweater with a coffee stain and knew more about kindness than any sermon I’d heard. We pulled reports, froze what could be frozen, flagged what needed flags. I went to the bank where a manager said, “We’ve been expecting you,” and I didn’t take it personally. I printed affidavits and signed with the hand that belongs to me.

My sister texted me an apology that read like a caption. Crazy night lol didn’t know that’s how it went down. I stared at the screen until it timed out. Then I typed, I accept apologies that use the word I more than once, and put the phone face down on the table. She didn’t respond. Later she posted a selfie with lyrics about storms and ships and didn’t tag anyone.

People asked what I wanted. I wanted a dog. I didn’t get a dog. I got a plant instead, because I wanted to prove to myself I could keep something alive without bleeding for it. The plant didn’t care about the party. It cared about light and water and whether I remembered to turn it so it wouldn’t lean too far and snap.

I went to physical therapy and learned my body’s new way to be strong. The therapist taught me a word I liked: glide. It describes how joints are supposed to move, not in one dramatic arc but with tiny, faithful slides. She showed me how to trust my leg to take me across a room, down a block, up a flight of stairs with a bag of groceries in my hand and the breath to say good morning to a neighbor.

Work, oddly, got easier. It is simpler to marshal a spreadsheet than a family. Numbers either add up or they don’t. I found that the part of me that had learned to read the fine print in my own life could read it for others, too. My boss handed me contracts and said, “Find the landmines.” I did. A client sent an email that said, How did we ever do this without you? I didn’t know. I didn’t ask. I bookmarked the sentence and let it exist without caring how long it would last.

A month after the party, a letter arrived from an attorney whose name sounded like a door I wouldn’t open. Cease and desist, it said, as if my living were a speech I should stop making. I took it to a lawyer who charged less than I feared and more than I wanted to spend. She read it, chewed the cap of her pen, and said, “They’ll lose if they try to push this into a courtroom. But don’t bluff. Document everything. You already have?”

“I do,” I said, and slid the binder across the desk like a gift.

She smiled. “Of course you do.”

My parents took my name off two accounts without argument after that, off three after the second letter, off the rest when my lawyer sent a draft complaint that had the words exhibit A arranged in a future they didn’t want. They asked for a meeting. I said no. They asked for a call. I said email. They wrote that they hoped to put this unpleasantness behind us. I wrote that unpleasantness is a euphemism for things you did. I wrote that when they were ready to write we did, I would read it. Until then: more documents, please.

Spring found me sitting on a bench outside the courthouse while my lawyer walked inside to file one last piece of paper that would take my name off the last loan. The bench was cold. The light was bright. A man fed pigeons wheat crackers and told them his doctor said not to eat so much salt. I wanted to tell him the pigeons didn’t care. I wanted to tell him I did.

“Ms. Johnson?” a voice said. It was the business partner who had left the party with his disgust as his coat. He looked older in the day, less crisp. “I wanted to say,” he began, then stopped. “I didn’t know.”

“You weren’t supposed to,” I said. “That was the point.”

He nodded, a little ashamed of his own comfort. “If you ever need a contact—”

“I have what I need,” I said, and it struck me that it was true.

Not all of it was triumph. The first time I took a different route home and accidentally turned down my parents’ street, my throat closed as if my body remembered the porch and wanted to walk me there to lie down and finish the story the old way. I pulled over and shook and told myself I was allowed to be a person whose hands still tremble when certain houses come into view. Then I turned around and went home.

Not all of it was ruin for them. People have a way of softening their view of those who make them feel comfortable. My parents told a story where I was unstable, where the crash had been a cry for attention, where the party had been an ambush. Some friends took that story happily; it saved them the work of seeing something ugly. That is their right. The sky doesn’t fall because three people look up and say it’s fine.

One afternoon my sister knocked on my door. I watched her on the camera for a full minute before I opened it. She wore no makeup, which is how I knew she had rehearsed sincerity. She held a takeout coffee and set it on my step like an offering.

“I,” she began, and her mouth moved around the word like she was trying a new food. “I was cruel. I repeated our parents’ cruelty because it served me. I’m sorry.”

I left the chain on. “That’s three ‘I’s,” I said. “It’s a start.”

She breathed out like she’d been underwater. “I don’t expect you to forgive me.”

“Good,” I said, and meant it kindly. “Expectation is just another way to do to someone. You’re not ready to do for. Learn that difference and we’ll talk.”

She nodded, awkward and earnest in a way I’d never seen. She left without asking to come in. The coffee went cold on the step. I poured it down the sink and rinsed the cup, then put it in the recycle bin. Forgiveness may one day happen. It won’t be a party trick.

The crash left a scar above my eyebrow that makeup barely blurs. Sometimes in the mirror I catch a glimpse of it and feel myself on the porch again. I don’t flinch. I say you got up out loud to my face. It sounds silly. It also works.

Summer came with a heat that made the plant ecstatic and the sidewalks mean. I learned the trick of walking on the shady side. I learned, finally, how to say no to people who offered me small rescues that came tied to big strings. I learned how to be in rooms where my parents’ friends pretended not to remember my name. I learned how to laugh anyway.

In August, my landlord sold my building, and for a day I was nineteen again, afraid that any change in someone else’s life would crush mine. Then I found a place three blocks away with a kitchen that understood me. I moved the plant and my binder and the mugs that feel right under my hand. I hung a cheap print over the couch that reads Nevertheless, she filed. I know it’s ridiculous. I know it’s also exactly the right joke.

On a Tuesday in September, a letter arrived from my mother. It was not a lawyer letter. It looked like something you write after three false starts and an argument in a room you haven’t unpacked because you can’t bear to look at the boxes.

We didn’t mean to leave you on the porch like that, she wrote. We were late and didn’t realize how bad it was. She called it a mistake. She used the word if before we hurt you and then scratched out if and wrote that. She wrote, I miss my daughter. She did not write I am sorry without a but.

I put the letter on the table and walked around it like it might spark. Then I wrote back. You left me bleeding on a step and locked the door. That is a sentence that will always be true. Here are the things that must also be true if we are ever to speak in a room again: you will sign and mean the words we did, we knew, we chose. You will stop telling people I am unstable to make yourselves feel better. You will pay the debts you put in my name that remain. You will not ask me to come to parties meant to polish you. If you want to know me, you will meet me in a place with cheap coffee and no audience and we will speak plainly. Until then, do not write.

I mailed it. I felt nothing heroic. I felt like a person who had written out a grocery list and then gone to a store and bought the things on it.

Time did its small work. The investigation into the forged signature ended not with a gavel but with something less satisfying and more common: a warning, a note, a promise from my father’s lawyer that anything like it again would move from paper to handcuffs. My father’s business downsized. He told people the economy had turned. Maybe it had, for him. My mother found a new circle to orbit, people less particular about what their friends do when their friends think no one is watching. That’s how the world works. I did not appoint myself its fixer. I kept my plant alive and my passwords complicated.

On the anniversary of the crash, I woke before dawn and drove—not to their house, not to the intersection, but to the lake that sits three miles from town and pretends it is an ocean if you squint. The air was the kind that makes your breath visible. I stood at the edge and counted five slow breaths the way I counted in the bank lobby months before. The water didn’t care who I was. That is one of the things I love about water.

I wrote two lines in a notebook I no longer needed but still kept:

I am not a stray mutt.

I am not out of the way.

I closed the notebook and put it back in my bag. On the drive home I passed the turn that would take me to their street and didn’t take it without having to tell myself not to. That felt like a promotion.

In December, people asked if I would go to the party this year. There would be no party. They told friends they wanted a quiet holiday instead. I wanted one too, so I made one: a roast chicken that didn’t burn, two friends who told jokes badly, a neighbor who brought a pie with a crust that forgave us all. We put on music and didn’t dance well and I laughed so hard my ribs reminded me they were there. I went to bed at ten and slept like ceilings are supposed to look.

You want a neat ending, I know. You want apologies in a neat row and a family photograph taken at the end of a driveway with no blood in view. You want redemption that looks like a movie. I cannot give you that. My ending is the kind that counts, the kind you don’t notice if you don’t know what you’re looking at: the plant still alive; the email from my boss that says take the weekend and means it; the way I don’t rehearse conversations I’m never going to have. The way I don’t imagine their door opening for me anymore because I don’t stand on that porch.

Sometimes my sister texts a picture of a sky she thinks I would like. Sometimes I text one back. That is the size of our peace right now. It is enough.

Sometimes I see my parents at the grocery store. Once my father stared hard at the shelf like the label on a jar of marinara could rewrite a year. I pushed my cart past him and caught my reflection in the freezer glass. I looked like a person who could go home and make dinner and sleep. That was all I’ve ever wanted, and I have it.

After my car crash, I crawled to the door. They laughed and stepped over me to leave for dinner. Here is what came after: I stood up. I kept standing. I learned that love is not proven by how low you will crawl for it, and dignity is not a thing anyone can hand back to you.

If they ever come to my door again, I will open it or not, as suits me. I will not beg at thresholds. I will not bleed on rugs for anyone. I will not be out of the way.

This is my house. This is my life. The lock turns from the inside.

The End.

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

At The Bank, My Dad Tried To Make Me Sign Everything Away, But Manager Read The Note I Hide. CH2

At The Bank, My Dad Tried To Make Me Sign Everything Away, But Manager Read The Note I Hide …

My Son Pushed Me at the Mother’s Day Dinner: “That Seat’s for My Mother-in-Law—Get Out.” So I Did… CH2

My Son Pushed Me at the Mother’s Day Dinner: “That Seat’s for My Mother-in-Law—Get Out.” So I Did… Part…

Dad Gave My College Fund to My Stepbrother’s Startup – The Email I Forwarded Changed Everything. CH2

Dad Gave My College Fund to My Stepbrother’s Startup – The Email I Forwarded Changed Everything Part 1 “Your…

My Sister Took The Money From My Room And Spent It. She Thought I Was Going To Cry, But I Smiled… CH2

My Sister Took The Money From My Room And Spent It. She Thought I Was Going To Cry, But I…

My Parents Forced Me To Give My Penthouse To My Sister. When I Refused — Dad Slapped Me, So I… CH2

My Parents Forced Me To Give My Penthouse To My Sister. When I Refused — Dad Slapped Me, So I……

My house was destroyed by a tornado, so I went to my son’s place. He said: “We want privacy”. CH2

After a tornado destroyed her home, Pauline Mercer turned to her son—only to be told, “We want privacy.” Alone and…

End of content

No more pages to load