After My Accident Dad Texted “Can’t This Wait? We’re Busy.” Three Weeks Later I Showed Up With Some Papers…

Part I — 3:15 A.M.

The ER lights don’t blink. They hum. They make you believe time has a sound, and it is fluorescent.

I remember everything and nothing. The cold of the gurney under my spine, the sweet-metal taste of blood in my mouth, the way my right leg belonged to someone else. Massachusetts General had seen worse, the doctor said. He moved around me with the practiced grace of someone who has carried people over thinner edges. Internal bleeding. Ribs like cracked porcelain. A clavicle in two neat pieces, like it couldn’t choose which half to love more.

“There’s a complication,” he added, not unkind. “You had an anesthesia reaction on record. We’ll have to use a different protocol. Hospital policy requires a family consent.”

My hands wouldn’t steady enough to swipe, to tap, to find the right name in a list that felt like it had been written by a stranger. I called my parents—Robert and Linda—three times each. The calls spiraled into the same void they always had. Voicemail. Voicemail. Voicemail. My own voice sounded unfamiliar asking them to please pick up, please, I need you.

At exactly 4:26 a.m., my phone vibrated in my palm. A text. From my father.

Can’t this wait? We’re busy meeting with clients.

Busy.

The word split me. Not my bones—that had already happened—but my belief. Family, I’d thought, meant that when the worst moment of your life finally arrived, you would not have to narrate it alone. Family meant someone showed up. At 4:26, family meant a man in a suit asking his daughter to schedule her emergency surgery around his calendar.

I laughed. It came out mangled, a broken sob that made my ribs scream loud enough to drag the nurse back in.

He was the kind kind. His name was Ben and he had hands that knew how to find a vein on the first try and a voice that said you are not alone even when he only said, “Hey.”

The social worker’s name was Maria. She felt like the way some people’s kitchens smell—warm, practical. “Anyone else?” she asked, and her eyes made it sound like a choice, not a test.

“Grandpa,” I said, because if there had ever been anyone, it was William. My mother’s father. A retired carpenter who still smelled like sawdust and coffee in the same shirt.

“I’ll call him,” Maria said, and walked out like she was going to tell God to get in line.

He arrived in forty-seven minutes. He was seventy-four and the hospital’s automatic doors opened for him like they had always been waiting to. He took my hand like it was a tool he still knew how to use. “Oh, May-bell,” he whispered and his voice was a porch light and I was ten again, mud on my knees, proud.

He didn’t flinch when the doctor talked about risks. He asked questions like he built things—measure twice, cut once. He took the clipboard with both hands, read it with his glasses low on his nose, and signed. He pressed his mouth to my forehead in a kiss that smelled like mint gum and sugar and promise. “I’ll be right here when you wake up,” he said. “Kid, don’t you worry.”

The light when I woke up was softer. He was still there, half-asleep in one of those torture-chair-contraptions hospitals call recliners. His hair looked like he’d fought a wind and won. He had a crossword folded over on 17-down. Clue: “unconditional.”

“I told you,” he said when my eyes finally found him. “I’m right here.”

Something inside me unclenched, and in the space that feeling made, my entire childhood stood up and walked up to my bed. My parents at fundraisers with glossy plates, me in my Goodwill dress, careful to eat without touching the napkin, careful to make my laugh polite. The day I brought home straight A’s and Mom said, “That’s nice, Mabel, but are you thinking about grad school?” The time I bought a used Corolla with 85,000 miles and a dent the shape of someone else’s mistake and Dad said, “When are you going to get serious?”

Grandpa had been the one to stroke my hair under a rain-soaked tent at my college graduation while they sent a photo from a conference in the Bahamas: “Wish we were there!” He’d been the one with chipped mugs of hot chocolate after I told him I loved working at a nonprofit even if it didn’t make a number in a bank account do a trick. “Anything made with love is worth more than something bought with money,” he’d said, and he had meant it enough to live it.

He was the one who showed up. Again.

They came four days later. My parents. Robert wore a suit even to hospital rooms and Linda’s bag looked expensive in a way that would never fit in a world where people wore gowns that let your ass hang out. She handed me a plastic bag. “Candy,” she said, apologetic. “Parking is awful.”

My father paced near the window. He checked his watch like the sun needed to know the time. “What’s the timeline?” he asked. “When do they think you can get back to work?”

It took me a second to understand what he was asking. Not—are you in pain? Not—what did the doctor say and should we call someone? When. When can you start being useful again.

They lasted thirty-five minutes, measured with the precision of a client lunch. They left to make a dinner reservation. The door clicked and the silence came to sit on my chest.

The surgeon said I’d be discharged in a few days. “Second-floor walk-up?” he asked, scanning my chart. “You’ll need ground level, six weeks at least.”

“Ground level,” I said. “Right.”

“Good,” Grandpa said from the corner. He had turned a chair around so he could sit with his arms folded over the back of it like a teenager. “She’s coming home with me.”

He had already built the ramp by the time we got to his one-level house in the small town where the light and the cold both made everyone honest. “Just until you’re steady,” he said, which I already knew meant as long as you need.

At night, under a yellow lamp and an old afghan that smelled like every dog we ever had, I learned the name for what had happened to me. Learned helplessness. It’s not weakness. It’s training. 26 years of making myself small next to people whose love required trophies. It had taught me to accept crumbs and call it dinner. It had taught me that if you failed to make the grade, you were the grade that failed.

The training was over.

Part II — The Mail

Sarah from downstairs knocked with her knuckles and ducked in before we said come in. “Your mail,” she said and lifted a box that would have made my clavicle scream if I had tried to pick it up. She set it on the farmhouse table first, then turned to hug me loosely, careful of compromised bones. “I didn’t want to bother you while you were…you know.”

“Nearly dead?” I said, and she winced and then laughed because we both needed it to be joke-shaped.

The box overflowed with envelopes. Medical bills in faux-kind font. Insurance statements pretending to be friends. I sorted them into two neat stacks and then ran my finger under a crisp seam on an envelope that didn’t match anything else. Disability insurance. The policy I had through work and the supplemental one Dad had set up when I was twenty-four. We had sat in his glass office then, the one with the view and the floor that made your shoes sound successful.

“It’s standard,” he’d said. “Add us as proxies. It’s all part of the family portfolio. Makes things easy.”

I had signed. Grateful. Flattered. Twenty-four is an age that aches with both.

On hold with a cheerful voice for twenty minutes. Then a human who said, “We’ve been in touch with your financial proxies, reviewing liquidation.” She said the word with the kind of background music that made it sound like an option on a drop-down menu. “Liquidate what?” I asked. “The entire fund,” she said. “Inquiry made three days after your accident.”

I hung up and called my father.

His voice had the easy swing of a man in control of a game. “We were wondering when you’d call,” he said.

“You tried to liquidate my disability fund,” I said. “Three days after my accident.”

“We’re restructuring assets,” he said. “The market is volatile; it’s a bad time—”

“Restructure where,” I asked. “Into what.”

He sighed, and the sound had the same music as a credit card ad. “The firm is having a temporary cash flow issue. It would have been a loan. Don’t be dramatic.”

A loan. For the money that was supposed to keep my apartment full of light and my fridge full of food while I learned how to put a T-shirt on over a broken clavicle. For money that would buy me a ramp and a lift and dignity.

“That’s theft,” I said.

He laughed. He hung up.

In the stack, at the bottom, an envelope from a bank whose brand colors I hated. Inside—decline letter, home equity line of credit. The application claimed I had applied two days after the accident. The address was mine. The co-signer field listed a man who shared my last name.

I did not feel my heart. I watched my hand hand the letter to Grandpa.

He didn’t say “I knew it.” He didn’t say anything about blood or family or forgiveness. He disappeared into his small office and came back with a leather-bound address book and the landline. His finger ran down a list of names written in his small careful printing. He dialed. It rang twice. “Harrison,” he said. “It’s William. Yes. I’m calling about my granddaughter.”

Mr. Harrison’s voice had been made of gravel and tobacco thirty years ago when he’d helped Grandpa settle a property line dispute with a neighbor. It had mellowed into mahogany. He listened like a man who had time and a pad of legal paper. I told him about the hospital. I told him about the text. I told him about the liquidate and the loan and the timeline and how it had always been timeline with Robert.

“What your parents did was not just unkind,” he said when I finished. “It was illegal. Predatory. We will revoke any existing power of attorney. We will cease and desist. We will notify every financial institution of fraud. We will put flags on your credit. We will name your grandfather as proxy for medical and financial decisions.”

He paused. “You rest,” he added. “We work.”

The papers arrived by courier the next morning. Grandpa made coffee like it was a ceremony. Mr. Harrison brought his briefcase and put it on the table like an offering. I signed my full name slow enough to make each letter count. We notarized faces. We mailed copies. We set the trap.

Four weeks, an ice storm, and a dozen physical therapy appointments later, I called my parents.

“Come to Grandpa’s at two,” I said. “Bring yourselves. That’s all.”

They arrived like they owned time.

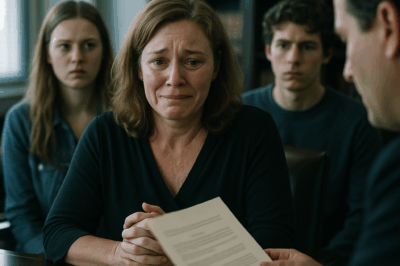

“What is this?” my father asked, all stainless steel and impatience.

“Whatever it is, Mabel, it has to be quick,” my mother said. “We have a showing at three.”

Mr. Harrison sat on one side of me. Grandpa on the other.

“These are revocations,” I said, sliding the thick manila envelope across the coffee table. “Power of attorney. Proxies. Beneficiary designations. All of it. Consider this a cease and desist as well.”

My father laughed until he saw Mr. Harrison’s card peeking from the top of the stack. “Ungrateful,” he hissed, color rising. “After everything we’ve done for you—”

“Like applying for a HELOC on my condo while I was under anesthesia?” I asked. I let the word land. “Like trying to liquidate my disability fund while Ben was threading a line into my vein?”

My mother’s professional smile slipped. “You don’t understand the pressure—”

“I do,” I said. “I understand you married the pressure. It kept you warm.” I kept my voice even. It surprised me how steady it was. “Sign.”

He did. Rage makes people efficient. She did too. Tears made hers blur and the notary made her sign again. They left in a silence that was a relief and an indictment.

The door closed. My breath went in and out like it learned how to do when it believed in lungs again.

Part III — Aftercare

Mr. Harrison stayed until the mail carrier came. He liked to hold envelopes that mattered. He put three letters into the slot and patted the door like it was a team. He put copies of everything in a yellow folder and gave it to Grandpa. He hugged me, shook Grandpa’s hand, tipped his hat like men do when they are old enough not to be embarrassed by doing that, and left.

“Soup,” Grandpa said.

“Soup,” I agreed.

After the first spoonful, after my body remembered to be grateful to something hot, I pulled my laptop closer. “I’m selling the condo,” I said.

Grandpa nodded like he’d known since the ramp. “Ground level,” he said.

Ground level, a postage stamp patio, a view of a tree that turned gold in October and dropped leaves in a way that felt like a weekly holy day. I found it. I bought it without including anyone in the conversation who might ask me if I’d thought about the tax implication. I could think about the tax implication. I could also think about not waking up on a staircase with a clavicle shrieking in a dialect only orthopedists speak.

We moved me in with three friends and a rented van and Grandpa’s half-ton with the busted tailgate. Sarah baked a pie because she is the kind of person who bakes pies for actions she didn’t take and cannot help. Ben came on his day off and taught us how to lift without swearing. He failed at that part. Grandpa built a ramp that he said was temporary and anchored like he’d been paid by a town.

At work—I had a job, a nonprofit coordinator position that made my parents purse their mouths when I said the word before and made me know enough about miracles to never use it professionally—I sat across from my boss and proposed a program. “We’ve been letting our people drown,” I said. “Hospitals discharge folks into a world that knows how to take advantage of them before they can get on a bus. We need legal and financial advocacy for medical survivors. We need a hotline for ‘My dad is trying to liquidate my disability fund.’ We need pro bono partners. We need to be the number you call after 3:15 a.m.”

She squinted at me. “We can try,” she said. “We can write grants. We can pitch stories. You can use the pad you learned to carry.”

I did. The first case was a woman named Nadine whose sister had opened a credit card in her name while she was in a coma. The second was a kid named Luis whose mother’s boyfriend had tried to swap the direct deposit on his settlement into an account with his name on it. We set flags on their credit. We revoked powers of attorney like we were calling down angels from a place Dad thought he owned. We taught social workers how to listen for paper.

I slept at night. Like, actual sheets and darkness and the kind of dreams that don’t wake you up panicked and broke. My clavicle stopped being the first thing I introduced myself with. My leg remembered weight. I learned to shower without crying.

My phone still buzzed. My parents learned to stop texting without purpose. They learned the words “We were wrong,” the way some people learn to pronounce hard consonants. They learned that sentences matter. They learned to stop asking and start apologizing. They didn’t do it often. They did it once, and it was enough to start choking down the guilt that would try to feed me forever.

My father said, in a text, “The firm is closing,” and I put the phone facedown and did not reply until morning. My mother showed up once, in a sweater that made her look like she had borrowed warmth, and said, “I have started therapy,” and when she cried, I did not. I made tea. We sat at the table. We did not mention mortgages. We said the name William and watched it make the air kind.

Ben came to dinner and taught Grandpa to cheat at cards using nothing but a raised eyebrow and a cough. Sarah brought that pie. Mr. Harrison sent flowers one day that looked expensive and smelled like funerals and I sent him a photo of my clavicle, with a caption that said, “Healed enough to carry whatever needs carrying.” He wrote back, “That’s exactly the right amount.”

Part IV — The Return

Three weeks and an ice storm after the papers were signed, my mother texted, Dinner Sunday? Just us.

Danielle—it’s always a Danielle in these stories, a cousin or a friend or a coworker who sees you without needing to be drunk to do it—wasn’t a cousin in mine. She was me and my mirror and my checkbook balanced. She said, “Ambush or casserole?”

“Both,” I said, and went anyway—not because the casserole was worth it, but because I needed to see if the ambush could be dismantled in a small room.

Her condo—sleek, white, expensive—smelled like meatloaf that was trying. She had a bandage on her finger and glass in the trash.

“Parking,” she said, out of habit, and then laughed at herself. “How are you?” she asked, and it surprised us both.

“I’m happy,” I said, and it surprised me enough to say it twice in my head without breaking.

We ate. We didn’t talk about the accident until dessert. We ate pie that had a crust that might have been made with the fat you use when you learn to let yourself use enough. She said, “We raised you to take it. I’m sorry. We made you durable and called you unbreakable and then we put the weight on you because it was easier than learning to lift it ourselves.”

I didn’t hug her. I didn’t stand and perform forgiveness. I said, “Let’s learn to use less weight,” and then I drove home in a snow that looked like static and let myself smile at a red light without worrying about why.

Grandpa watched me come in. He tried to play it cool and failed. “Soup?” he asked. He did not say, “Winning feels like this.”

“It does,” I said anyway, and sat on the sofa he loved that used to belong to a dog we both loved.

Some people asked why I didn’t hit my father back—legally, emotionally—with the kind of righteousness a person is owed. The thing about debts is that sometimes you pay them by choosing not to owe yourself another uglier one.

He sent one more text: I’m sorry. For the hospital. For the loan. For the child I tried to raise into a client.

I sent: Thank you. That’s all.

Part V — The Papers

Three weeks after the hospital, after the text, after the papers, I went to the post office with Grandpa. He always goes in. He doesn’t like the blue mouth on the street. He trusts hands.

We mailed the last of the corrective documents: beneficiary changes finalized, proxies revoked, fraud alerts renewed. He bought a book of stamps with birds because he likes to hide them in drawers for me to find.

“Papers,” he said on the way home, like a man appreciative of their weight. “Saved me once.”

“How,” I asked, because I want to know the history I wasn’t made to live.

He told me about a man who tried to cut his land line and take five feet of yard with it. He told me about a plat map and a surveyor and Mr. Harrison who was a baby then and a rope he stretched between two stakes with a certainty that made bullies tired. “Papers,” he said. “Good for when people forget what a line is for.”

I kept a folder of everything on my top shelf, labeled in a handwriting that looks like mine and my mother’s mixed. I looked at it once a month, not to admire, but to remind myself that protection is not paranoia.

On a spring day, sunlight slanked across my kitchen floor like a dog. I made coffee in a mug I threw in pottery class and the handle didn’t fall off because I threw it again three times to make it right and no one was there to tell me that meant I was imperfect. I looked around at people who were not there and people who were. Grandpa painting birdhouses on the patio. Sarah watering herbs. Ben texting me a photo of a crossword clue, 17-down.

“Unconditional,” I texted back. He sent a heart.

I had dinner that night with a table of people who remember the answer to that clue and not just because we memorized it.

You want an ending. You want me to tell you that my parents became better. Or that they got worse. You want me to tell you whether I forgave them or forgot them. You want me to tell you which of those is a better story to tell yourself when it’s your turn to choose. It’s messier and kinder than that.

I have papers. I have a ramp. I have a clavicle that holds. I have a job that turns fury into forms and then into protection for people who don’t know how to use either yet. I have a grandfather who says, “Soup?” like he’s asking me to marry the inside of my certainty. I have a neighbor who brings pies. I have a nurse who knows how to find a vein and a smile in the same place. I have a room that smells like coffee and a life that smells like coming home.

When someone texts you “Can’t this wait? We’re busy” while you’re bleeding under fluorescent light, you are allowed to answer them with papers three weeks later. You are allowed to make your life into a document that tells anyone who looks that your body is yours, your accounts are yours, your breath is yours.

You are allowed to heal.

And then you are allowed to open your door to the right knock.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will

After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will Part One I never thought I’d…

When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night

When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night Part One…

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement Part One I never…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then… …

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead Part I — The Test Shot…

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything Part 1: The…

End of content

No more pages to load