After I refused to pay for my daughter’s over-the-top wedding, she stopped speaking to me. A few days later, I got an invite to a family reconciliation dinner. But when I arrived, three lawyers were sitting at the table with legal papers. She smirked and said, “Sign over power of attorney or you’ll never see your grandson again.”

Part One

I stayed calm, reached into my purse, dialed a number, and said, “Can you believe it?”

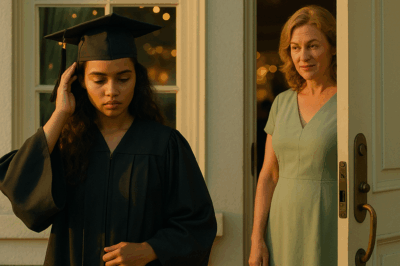

My own daughter—my Annie, the one I poured my entire life into—looked me in the eye and demanded my life’s savings. And when I said no, she threatened to cut me off from my future grandchild. It all started with a dress, a burgundy one in my closet. I’d worn it for every one of Annie’s big moments: her high school graduation, college commencement, even her first big promotion. Each time she’d say I looked elegant, that she was proud of me. But as I smoothed that familiar fabric over my sixty-two-year-old frame, a dread took root. Would this be the last time I ever dressed up for my daughter?

Three weeks. That’s how long it had been since our explosive argument about her wedding budget. Sixty-five thousand dollars. Not requested—demanded. As if my late husband Harold’s life insurance, the nest egg we had so carefully protected for my retirement, belonged to her by birthright.

“Mom, you’re being selfish,” she snapped, her voice as sharp as a winter gale. “You’re sitting on all that money while we’re trying to start our life together. Don’t you want me to be happy?”

“Happiness doesn’t require imported Italian marble,” I said, “and it certainly doesn’t need a destination honeymoon in the Maldives.” I offered fifteen thousand—enough to cover a beautiful local ceremony. But Annie’s face was cold with contempt. I barely recognized the little girl who used to bring me dandelions and call them sunshine flowers.

On a quiet Tuesday morning, while I was pruning the deadheads from my climbing roses, the phone rang. Annie. Her voice sounded different—softened, almost vulnerable.

“Mom, I’ve been thinking about what you said,” she began. “Maybe we’ve both been too stubborn. Could we talk over dinner? I want to work this out.”

Hope swelled. Maybe the silence had given her time to think. Maybe the pregnancy—three months along now, barely showing—had awakened in her an understanding of sacrifice, the weight of protecting what you’ve built.

“I’d like that, sweetheart,” I said, already picturing the casseroles I’d cook, the words I’d find to stitch us back together.

“Actually,” she added quickly, “Henry and I thought we’d take you out somewhere nice. You know that Italian place on Meridian? Franco’s?”

Franco’s. The name alone buckled me with memory. Harold took me there for our twenty-fifth anniversary. Warm brick. Overflowing window boxes. Candlelight so gentle it forgave everything we didn’t yet know about how to grow old together. I dabbed my lipstick, pinned on Harold’s antique brooch, and let myself feel genuine hope for the first time in weeks.

The drive to Franco’s took me past Annie’s childhood landmarks: the elementary school where I volunteered shelving library books; the park where I pushed her on the swings until my arms trembled; the community center where, at thirteen, she stood on my toes as I taught her the waltz. Each place was a page in a book I wasn’t ready to close.

Franco’s was exactly as I remembered: warm brick, soft jazz, low amber lighting. “Six-thirty,” the hostess smiled. “Your party’s already here.” She led me toward a corner table. Annie rose to meet me, radiant in a dress I didn’t recognize—designer, probably cost as much as two months of my groceries. She smelled of expensive lilies. It hurt, the beauty of her.

“You look beautiful, Mom,” she said, and for a second I was just a mother again, undone by my child’s praise.

“How are you feeling? Any morning sickness?”

“Better. Second trimester’s supposed to be easier.” She touched her belly with a gesture that was both protective and possessive. “Henry should be here any minute. He got held up at the office.”

Henry Smith, thirty-six. Commercial real estate. Handsome in that glossy, unrumpled way of men who have never had to get their hands dirty. He shook my hand when he arrived, flashed his polished smile—and ushered three men in suits to our tiny table.

My stomach tightened. Not a coincidence. A strategy.

“Mrs. McKini,” Henry beamed. “Thank you for joining us.” He gestured at the men. “These are colleagues. They’ve brought some paperwork for you to review.”

The silver-haired one gave me a predatory smile that transported me back twenty-two years to my old job at the law firm, to the partners who could dress extortion in silk. “Richard Kirk,” he said smoothly. “We’ve prepared documents we believe will be beneficial for everyone involved.”

“What kind of documents?” I asked, though I already knew.

Henry interlaced his fingers. “It’s really quite simple, ma’am. A durable power of attorney. Given your age—”

“I’m sixty-two,” I cut in.

“Of course,” he said, patronizing. “But financial markets, property decisions—it’s complex. We’d like to remove that burden from you.”

I turned to Annie. “And if I don’t sign?”

She finally met my eyes. The expression there was one I’d never seen on her face: cold, calculating, final. “Then you won’t see your grandson. It’s your choice, Mom.”

The clink of glassware, the murmur of conversation—all of it dissolved to a distant hum. I looked at my daughter and tried, truly tried, to trace the winding path that had turned sunshine flowers into legal threats.

“I see,” I said quietly. I reached into my purse for my phone and found the number I’d saved two weeks earlier, when something inside me—call it intuition, call it the ghost of Harold’s steady voice—whispered that this dinner might be less reconciliation than ambush.

“Michael,” I said when my son answered. “It’s Mom. I need you to come to Franco’s. Yes, now.”

I ended the call and set my phone beside the manila folder.

“Before I sign anything,” I said, “someone else is going to say a few words.”

Twenty minutes later Michael appeared, breathless, still in his hospital scrubs, hair damp from a rushed shower. He took in the table—Annie’s glow, Henry’s smirk, the lawyers’ briefcases—and his face became the calm I’d watched him build since residency.

“Good evening,” he said to no one in particular. “What’s the occasion?”

Henry extended a manicured hand. “Henry Smith. Your sister’s fiancé. We’re just reviewing some financial plans with your mother.”

Michael didn’t take the hand. He lifted the folder, skimmed it, snapped it closed. “Power of attorney. Did Mom ask for this?”

Kirk cleared his throat. “Given the complexities—”

“Did she ask?” Michael repeated, soft but surgical.

“No,” I said.

“Then this meeting is over,” Michael said, his ER voice—gentle, immovable—landing like a gavel. “Gentlemen, give us a moment.”

The lawyers retreated to the bar, glancing back as if leaving their prey unattended violated some code. Henry’s jaw pulsed. Annie stared at her hands.

“Mom?” Michael asked, dropping into the chair beside me. “You okay?”

I told him about the fight. About the sixty-five thousand. About the threat of a grandchild used as leverage.

He listened without interrupting, fingers drumming an old rhythm—boyhood homework, cardiac rounds, the steady beat of deep thought. “Are you having problems?” he asked finally. “Memory, confusion, anything they could spin?”

I almost laughed. “Last month I balanced my checkbook to the penny, renegotiated my car insurance, and fought a faulty property tax assessment. I’m fine.”

He nodded once—diagnosis complete. “Good,” he said. His jaw tightened, the way Harold’s used to when he saw something wrong and couldn’t let it stand. “Because this is elder financial abuse, and I won’t let it happen.”

Henry returned with the lawyers arrayed behind him like a little army. “We have a timeline,” he said briskly. “Vendors to pay. Venues to book. We can get this done tonight.”

I stood, smoothed my dress, and smiled the way I’d learned in years of PTA meetings—pleasant, impenetrable. “You’re right,” I said. “Tonight is the perfect night for signing.”

Relief flashed across Henry’s face. Annie exhaled. Kirk’s pen hovered.

“Just not your papers.”

I reached into my purse and withdrew a thin, dignified stack. “Two weeks ago,” I said, “I established the Annie McKini Family Trust.”

Silence fell hard.

“An irrevocable trust,” I continued, meeting each gaze, one by one. “My house, my investment accounts, and the remainder of Harold’s policy have been transferred to it. The beneficiaries are my children—both of them—and any grandchildren. Michael is the trustee until they reach twenty-five.”

Henry’s composure cracked. “You can’t—”

“I already did.”

Kirk’s mouth thinned. The youngest lawyer swallowed. Annie’s face—beautiful, frightened—crumpled.

“The trust pays for education, healthcare, and reasonable support,” I said. “Italian marble bathrooms are not reasonable support.”

Henry’s voice wavered. “This is ridiculous. We—Annie and I—had an agreement.”

“Did you?” Michael asked, looking at his sister. “Or did you have demands backed by threats?”

Annie blinked hard. “I’m pregnant,” she whispered. “We need security.”

“You’ll have it,” I said. “But Henry won’t control a cent.”

Louise arrived twelve minutes later, small and silver-haired, her presence opening space in the room like sunlight. “Good evening,” she said pleasantly, settling her leather briefcase on the table. “I’m Mrs. McKini’s counsel. I understand you have documents you’d like her to sign.”

Kirk cleared his throat. “This is a family matter, Ms.—”

“Qualis,” she said. “And precisely because it’s a family matter, I’m here. To ensure my client’s family ties aren’t exploited for financial gain.” She turned to me. “Are you ready, Annie?”

I nodded.

Louise laid copies of the trust on the table like a magician laying down a final, unbeatable card. “Irrevocable,” she said mildly. “It’s a beautiful word.”

The lawyers’ retreat was graceless, paper stuffed into briefcases, phones pulled out for anxious calls. Henry hissed into Annie’s ear. Annie cried silently. Michael paid for our untouched drinks and offered me his arm.

On the sidewalk, Louise squeezed my shoulder. “You did beautifully,” she said. “Now comes the boring, healing part.”

“For the first time in months,” I told her, “I feel free.”

The days that followed shifted into a new rhythm. I slept through the night. I learned to make coffee for one without feeling unlucky. I volunteered at the Meridian Community Center’s new program for seniors facing financial exploitation—Diana, the director, had called at Louise’s suggestion. On Tuesday nights I sat in a circle of folding chairs with people whose children had forged signatures, whose spouses had siphoned bank accounts, whose caregivers had curated isolation. We told the truth. We practiced the dangerous skill of using words like no and mine and enough without apologizing.

Janet moved into the duplex next door. She was sixty-seven, brisk and kind, a widow with a practical haircut and a talent for cornbread. We became the sort of friends who borrow sugar without texting, who water each other’s plants, who say “You’re not wrong” instead of “I told you so.” She suggested we call my makeover of the house “the reclaiming project.” We sanded Harold’s old workbench. We painted the living room a soft gray. We bought a pair of mismatched mugs from a thrift shop and declared them perfect.

Henry’s business unraveled in quiet, satisfying ways that had nothing to do with me. The bank froze an escrow account. A partner discovered “irregularities.” A realtor friend told Janet he’d been seen arguing loudly with a client at a Starbucks, his voice panicked, his hands slicing air.

Annie texted Michael now and then, asking clinical questions about the trust, fishing for loopholes. She hinted that a broken engagement might soften me. Michael replied with sentences that were both kind and unyielding: Mom’s boundaries are not conditional. He asked me once if I thought he should try to “fix it.” I told him some things aren’t repairable, only survivable.

When Eleanor was born in late October—seven pounds, two ounces—Michael called me from the hospital. “She’s healthy,” he said. “They named her after your mother.” I felt the manipulation in the name, sharp as a pin, and I felt something else too, softer: wonder. A new person had entered the world. My granddaughter.

Annie sent word through Michael that she wanted me to visit. I sat with the invitation for a long hour, then I wrote a letter—clear, kind, armored.

Annie, I began. I would very much like to meet Eleanor. I will do so under terms that protect my ability to be a grandmother and not a target. Visits will be in Michael’s presence. Any attempt to discuss the trust, my finances, or past grievances will end the visit immediately. If you can accept these terms, Michael will arrange a time. If you cannot, I hope you will reconsider when you are ready to prioritize Eleanor’s relationship with her grandmother over your access to my money. I will always love the daughter you were. I am no longer available to be victimized by the woman you’ve chosen to become.

I sealed the envelope and, for the first time in a year, didn’t tremble when I walked to the mailbox.

Part Two

The community center smelled faintly of lemon cleaner and new carpet. On Tuesday nights, our group—twelve women, three men—folded ourselves into a circle that made space for grim stories and bright survivals. Maxine, seventy-two, wore sneakers and swore by Pilates. Eddie, seventy-eight, carried photos of a sailboat he’d sold to pay debts a daughter had hidden from him. Rosa, sixty, kept tissues on her lap and asked good questions.

“Tonight,” I said, “we’re talking about what comes after. After you’ve shut the door. After you’ve signed the papers. After you’ve said no.” Faces tilted toward me; some eyes were red, some fierce. “What did you build when you got your own life back?”

“I learned to like living alone,” Eddie said, surprising himself. “I didn’t know I could.”

“I learned I don’t have to forgive to be okay,” said Sheila, whose son had opened three credit cards in her name. “People kept telling me I had to because he’s my son. Turns out, my heart disagreed.”

“What about you, Annie?” Carolyn asked me. “What came after for you?”

“Purpose,” I said. “For forty years my purpose was being a wife and mother. After Harold died, I thought my purpose was protecting what we built so I could pass it on. But maybe my purpose is protecting other people’s mothers from what I went through.”

They nodded. That’s what I loved about that circle: we clapped for the quiet victories.

A new woman hovered by the door that night—carefully dressed, hair shellacked into submission, eyes full of that particular shock that comes with being betrayed by someone you loved. I broke the circle a little and beckoned. “First time?” I asked. She nodded. After the meeting we sat on the dinged wooden bench in the lobby and talked about how to be a person when your child has mistaken you for an ATM. “You cry,” I said. “You call a lawyer. You call us. And you make breakfast tomorrow, because breakfast is underrated as a rebirth ritual.”

Janet and I celebrated Tuesdays with soup and cornbread at my kitchen table. “How was group?” she asked that night.

“Good,” I said. “Hard. A new woman asked, ‘How do you stop missing who they used to be?’”

Janet sighed. “You don’t,” she said. “You just stop letting that longing drive.”

Two days later, Michael called. “Annie accepted your terms,” he said. “She’s… subdued.”

We set a time. Sunday afternoon. Michael would pick me up. He would stay in the hospital room with us. We would talk about Eleanor’s weight, not about marble bathrooms.

On Sunday, I wore the burgundy dress—the one from milestones—and Harold’s brooch. In the mirror I looked like a woman who could survive an ambush at Franco’s and still show up for love.

Annie was propped up in bed, pale and astonishingly young. There was a bassinet. There was the soft animal sound of a newborn’s yawn.

“Mom,” Annie said, small and careful.

“Annie,” I said, equally careful.

Michael lifted Eleanor into my arms. Seven pounds and some change; the weight of a library book hardened over time with meaning. She smelled like talc and possibility.

“Hello, Eleanor,” I whispered. “I’m your grandmother. I’m the one who will teach you to knead bread and write letters and wear shoes that don’t hurt just because they’re pretty. I’ll show you how to pay your bills and how to say no and how to stand up very straight when someone tries to make you smaller.”

Annie made a sound. When I looked up, she was crying in a way that seemed almost… honest. Not theatrical. Not strategic. “I’m sorry,” she said, and then, more softly, “I don’t know how to be someone different.”

“You don’t have to figure it out today,” I said. “You just have to not try to negotiate during this visit.”

She laughed wetly. “Okay.” She glanced at Michael. “Thank you. For being here.”

He squeezed her shoulder. “Feed the baby,” he said gently. “That’s your job today.”

I visited twice more in those early weeks, always with Michael. We kept to the rules. We talked about diapers and sleepy grunts and the way Eleanor’s toes looked like barley grains. Annie slipped only once—“Mom, about the trust—” and I stood, kissed Eleanor’s brow, and said, “Next time.” Annie nodded and didn’t argue.

January blew in hard and cold. I shoveled my walk in a new wool hat that made Janet call me “chic.” Our group at the center grew. Louise became a mythic figure: the silver-haired lawyer who’d outmaneuvered a small army of predatory sons-in-law. Volunteers baked lemon bars. We printed pamphlets with frank language: If someone says “sign,” say “I’ll have my attorney review it.”

Somewhere in February, Henry disappeared from our radar. A realtor friend said he’d left the firm “under a cloud.” Annie didn’t mention him. She sent a photo on Valentine’s Day of Eleanor in a red onesie with white hearts, and I discovered it is possible for a picture to make your chest ache and bloom at once.

On a Tuesday in March, the new woman from the lobby—her name was Brynn—brought a cake to group. “I filed for a restraining order,” she said, and the cheer that went up was not unkind, just very, very proud.

“Champagne would be tacky,” Maxine said, “but I wish we had some.”

In April, the community center asked me to facilitate a workshop: “Boundaries for Beginners.” I stood at the front of a room with a dry-erase marker in my hand and wrote a list on the board:

No surprise documents.

No signing under pressure.

No meetings without an ally present.

No guilt disguised as love.

No money without a plan.

No “family card” used as leverage.

“This looks like a lot of no’s,” a man in the back said.

“It’s how you make room for your yes,” I replied.

Spring brought tulips to my yard and a baby monitor to my phone for the afternoons I spent at Annie’s apartment while she showered or napped. Michael’s rules remained in place; we followed them; no one died of restraint. There were setbacks. Once, in May, Annie texted me a link to a “reputable” article arguing grandparents should fund grandkids’ 529 plans “as a show of commitment.” I sent back a photo of Eleanor asleep on my chest and wrote, This is my show of commitment. Annie didn’t reply, but the next time I visited she handed me a stack of board books and said, “Read to her. She sleeps better after stories.”

In June, our circle at the community center took on a case that mattered more than most. Rosa’s grandson had been arrested using a credit card that wasn’t his. The boy’s mother blamed Rosa, claimed Rosa had “tempted” him by leaving her wallet on the counter. Rosa cried onto her tissue and said she was tired, so tired. Louise walked us through steps. Michael dropped by to talk about addictions and brains and how love isn’t the same as access. The next week, Rosa arrived with her head up and her wallet zipped in her bag. “I pressed charges,” she said, voice shaking. “I love him. I pressed charges.” We applauded like she’d run a marathon.

In July, Annie asked if I’d like to take Eleanor to the park alone for an hour. “Just around the block,” she said, anxiety threaded through her voice. “I’ll be right here when you get back.”

“Of course,” I said. Eleanor wore a floppy sun hat and gripped my index finger with intensity. We walked slowly under cottonwood trees. I pointed out robins and dogs and the way wind makes puddles look alive. An older woman on a bench nodded at me. “Grandbaby?” she asked. “Yes,” I said. “First one.”

“How is it?” she asked.

“Terrifying,” I said honestly. “And wonderful.”

In August, I presented at a city council meeting during Senior Safety Month, my hands steady on the podium. I told the story of “a woman in her sixties whose daughter and future son-in-law brought three lawyers to dinner.” I described the trust, the ambush, the boundary letter. I didn’t name names. I didn’t have to. The room crackled with recognition. A reporter asked for a quote afterward; I told her: “Protecting yourself isn’t selfish. It’s how you make sure the next generation inherits wisdom, not wounds.”

Autumn came again. Eleanor turned one. Annie invited me to a small party in the community room of their building—paper lanterns, a homemade carrot cake, a circle of new mothers who smelled faintly of milk and hope. I brought a quilt I’d stitched from squares of Harold’s old shirts. Annie unfolded it and pressed her face to the fabric. For the first time in two years, I saw the girl who brought me dandelions.

“Thank you,” she whispered. “For this. For…” She gestured vaguely at the world between us. “For not giving up.”

“I didn’t give up,” I said, “I grew up.”

She laughed, shaky but real. “Me too, maybe.”

We didn’t talk about Henry. We didn’t talk about the trust. We sang “Happy Birthday.” Eleanor smeared icing into her hair. Michael took a photo of the three of us that I keep on my mantle—not as absolution, not as revision, but as evidence that a beginning can be something fragile and still matter.

One icy afternoon in December, Annie came to our Tuesday meeting. She sat in the back quietly, a scarf wrapped high around her neck. After, she waited while the room emptied. “Can I speak?” she asked, voice small.

“Of course,” I said, spreading a fresh tissue on my knee.

She took a breath. “I grew up thinking love and money were the same because every good thing I got came with a price: a performance, a promise, a demand. When Henry said ‘I’ll make sure your mother does the right thing,’ I heard it as love. When he said ‘Family means access,’ I heard it as truth. I am… ashamed. And I am sorry.”

No one clapped. It wasn’t a clapping moment. Janet stepped forward and handed her a small paper cup of water. Louise nodded, inscrutable. Michael, who’d stopped by to deliver a pamphlet, stood in the doorway and looked like a man who had waited a very long time to exhale.

“I can’t fix what I did,” Annie said. “But I can learn new words for love.”

“Start with ‘please’ and ‘thank you,’” Maxine advised, not unkindly.

“And ‘no,’” I added. “Start with ‘no’ where it belongs—in your own mouth.”

Christmas Day, Eleanor toddled across my living room, triumphant, clutching a wooden spoon like a scepter. We ate cinnamon rolls. Annie washed the dishes without being asked. Michael set up the tripod and took a family picture where no one pretended to be taller than they are.

After everyone left, I stood at the window with the house quiet and the lights soft. The burgundy dress hung in the closet, the brooch lay in its velvet bed. I did not feel triumphant. I felt… right-sized. Like a tree after a storm: branches missing, roots deeper.

In the new year, the community center offered me a stipend to coordinate the program. “We need structure,” Diana said. “And you’re good at drawing lines.” I took the job. I designed intake forms that asked the questions no one else would. I built a checklist to keep in your purse: If pressured, leave. If guilted, pause. If cornered, call. We added a Wednesday morning “Coffee & Contracts” clinic—Louise reviewed stranger-danger clauses in leases; Michael answered questions about capacity and consent; Janet, to everyone’s delight, taught a unit called “Spot the Smarm” using photographs of various salesmen she’d met in her long, vivid life.

One evening in March, I received a short email from Henry. I am sorry for my part in all of this. I didn’t reply. Some letters belong to the past tense. Some futures do not need footnotes.

In April, I stood in front of a room of social workers and said, “Here’s what you listen for: ultimatum words—‘if you loved me,’ ‘real family would,’ ‘after all I’ve done.’ Here’s what you teach: language that frees—‘I love you and I won’t,’ ‘I hear you and the answer is no,’ ‘I choose my peace.’” People wrote it down. They asked me to repeat it. I did, and my voice didn’t shake.

The second anniversary of Franco’s arrived. Michael suggested dinner there. “A new memory,” he said. We went—just the two of us—and ordered the sea bass. The hostess seated us near the corner table. “You were here once before, weren’t you?” she asked brightly.

“Yes,” I said. “It went very differently.”

We ate slowly and talked about ordinary things—his resident who kept forgetting lunch, my neighbor who’d started dating again at seventy-one. When the bill came, Michael pulled out his card. “Let me get this, Mom.”

“Thank you,” I said, and the ease of it—the simple reciprocity—made my eyes sting.

On the way out, I paused by the door. The room looked the same: warm brick, soft light, clean forks. I did not smell panic. I smelled garlic and wine and something else I recognized now: my own life.

If you’re waiting for a moral, here is mine: love without boundaries is leverage; family without respect is theater; “reconciliation dinner” without apology is a setup. When they brought lawyers, I brought a lawyer and a son. When they brought threats, I brought a trust. When they brought “sign or lose your grandson,” I brought a letter with conditions that made room for a yes that would not break me.

Annie still slips sometimes. In March she texted me a link to a “grandparent cruise.” I texted back a photo of Eleanor painting with pudding and wrote, We’re busy at camp Kitchen. She replied with a laughing emoji, then called to ask if I had the recipe for Harold’s cinnamon rolls. I did. I emailed it with the subject line: Family, not leverage.

Eleanor is almost two now. She says “Nana” like a secret and “mine” like a hymn. When she naps on my chest, the rhythm of her breath answers questions I don’t know how to ask. I tell her stories about Harold, about sunshine flowers, about the day she toddled toward the dog like a queen greeting a subject. I don’t tell her about Franco’s. Not yet. She will learn, in her own time, that her grandmother once sat at a table with three lawyers and a heart that wouldn’t break. She will learn how to hold her own pen.

The burgundy dress still hangs in my closet. I put it on for Eleanor’s baptism, for my promotion celebration at the community center, for a quiet dinner with Janet to mark the anniversary of her moving next door. It’s become my armor and my choir robe—what I wear when I’m both protected and singing.

And if you’re wondering what happened to the power of attorney papers, I kept them. I keep them in a file labeled “Lessons,” alongside a photo of Eleanor grinning with frosting on her nose, a copy of the trust, and the letter I mailed to Annie. When I take that folder down, I remember the simplest truth:

They demanded my signature.

I chose my voice.

They said “sign or lose.”

I said “no and love.”

They brought a threat.

I brought a boundary.

They tried to take my life.

I made a new one.

And when I arrived home that night from Franco’s, I hung Harold’s brooch back in its velvet box, poured myself a glass of water, and stood very still in my quiet kitchen. Then I did the bravest thing I have ever done: I slept. And in the morning, I made breakfast. Because some victories look like trust documents and exit lines, but the longest, truest ones look like toast, coffee, daylight, and a woman who cannot be moved.

END!

News

My parents evicted me from the apartment I was renting from them, so my pregnant sister and her fianceé could move in. ch2

My parents evicted me from the apartment I was renting from them, so my pregnant sister and her fiancé could…

VIRAL: Kayleigh McEnany’s baby Avery’s FIRST trip photo SHOCKS fans with a intriguing detail!

Kayleigh McEnany’s Heartwarming Reveal: Third Daughter’s First Trip Photo Stuns Fans with Shocking Detail! Fox News star Kayleigh McEnany…

At my birthday dinner, my sister announced she was pregnant with my husband’s child. ch2

At my birthday dinner, my sister announced she was pregnant with my husband’s child. She thought I’d fall apart. We’re…

Can you even afford this place? My sister sneered loud enough for nearby tables to hear. ch2

Can you even afford this place? My sister sneered loud enough for nearby tables to hear. She laughed, sipping her…

My parents left me at a train station as a joke. Let’s see if she can find her way home. ch2

My parents left me at a train station as a joke. Let’s see if she can find her way home….

At my graduation party, I was told to wait outside the venue. My aunt smirked, “This is just for close family.” ch2

At my graduation party, I was told to wait outside the venue. My aunt smirked, “This is just for close…

End of content

No more pages to load