A POOR GIRL Arrived WITHOUT SHOES at the INTERVIEW – MILLIONAIRE CEO CHOSE Her Among 25 CANDIDATES

Part One

The heel snapped with a sound like a gunshot.

Blair Evans stared down at the crooked strap as if sheer will might fuse it back together. It didn’t. The cracked wedge dangled helplessly from her ankle while commuters streamed around her on the sidewalk, irritated the way city people get when someone dares to be human near them.

“Great,” she muttered to no one. “Perfect. Ten out of ten, life.”

Nine blocks still yawned between her and the mirrored high-rise whose name—ZNK CORPORATION—looked like a verdict in chrome across its facade. It was the kind of place you stared at from a city bus and thought, People who know what they’re doing work there. She had exactly sixteen minutes left, and she had no Uber money, no spare shoes, and no time for miracles.

She tried to limp forward on the remaining heel, made it three steps, and collided with a wall in a suit.

Both of them staggered. Blair’s tote exploded—résumés, references, a bus schedule, two pens, and a crumpled granola bar burst across the concrete like a fortune-teller’s spilled cards.

“Watch where you’re going,” said the wall, except the wall had a voice like cold glass and a phone pressed to his ear. He hadn’t even looked up when they’d collided, and he didn’t now. He was tall, immaculately dressed, and preoccupied with a world that didn’t include people who tripped near him.

“You broke my heel,” Blair blurted, because sometimes your mouth works faster than your sense of self-preservation. “How am I supposed to show up to an interview like this?”

“If you’re really good,” he said without sympathy, “a broken heel won’t stop you.”

“Wow,” Blair said, eyebrows jumping. “Do you also embroider bland inspiration on throw pillows, or is that just a part-time gig?”

For half a second the line at the corner of his mouth hinted it might be a smile. Then the phone owned him again. “Good luck,” he said, already walking away.

Blair stood with one broken shoe in her hand, snatches of her hurried life gleaming on the sidewalk, and a decision waiting like a red light you choose to run or not.

“Fine,” she said to the city. She yanked off the other shoe, shoved both into her bag, gathered every one of her papers, lifted her chin, and ran barefoot.

She burst into ZNK’s lobby with her hair clinging to her forehead and asphalt dusting the arches of her feet. Polished metal and marble turned her into a bad punchline. The receptionist—a woman in a blazer that could probably pay Blair’s rent—blinked at the sight.

“Interview for the executive assistant position,” Blair said, trying to sound less out-of-breath than she was. “I’m Blair Evans. I’m a little—”

“Late,” the receptionist supplied, tapping the screen of a sleek tablet. “Fourth floor. Take the second bank of elevators.”

Blair hustled down a hallway and into a waiting room where twenty-five women sat poised like magazine covers. Their hair gleamed. Their heels gleamed. Even their folders gleamed. Blair had a secondhand blazer, a neat ponytail that humidity had ruined, and toes that looked like they belonged to someone who had wrestled a sidewalk and lost.

She hid her broken shoes beneath her bag and sat. A few candidates glanced at her bare feet and stifled giggles. The blonde nearest the window lifted her phone and “checked her messages,” camera angled exactly right.

“You’re killing this,” Blair whispered to herself. “Positive spin: you took ‘casual chic’ to the next level.” She forced her shoulders down and ran through her talking points. The rent was two months late. The electric company had called twice. This interview was not a luxury. It was oxygen.

Footsteps approached, measured and unhurried. A man entered with a stack of folders and a face Blair recognized with a jolt. The sidewalk. Mr. Inspiring Throw Pillow. He paused when he saw her, his gaze an even line that gave nothing away. Someone snorted. The room’s temperature dropped three degrees. He continued to the head of the table and set down the folders with a orderly click.

“Good morning,” he said. “I’m Derek Crawford, Chief Executive Officer of ZNK.”

Blair’s stomach did something between a swoop and a laugh. Of course. Of course the entire universe had decided to be a farce.

“Ms. Evans?” the receptionist called from the doorway. “You’re first.”

Blair stood. The room went quiet the way rooms do when someone’s about to be fed to lions for sport. She walked into the conference room barefoot and prayed to every god of carpet.

Derek sat at the head of the long table in a suit that looked custom-everything. Up close he was less marble and more…edges. Clean lines, steady eyes. The kind of man who trained himself out of fidgeting by age eighteen.

“Blair Evans,” he said, scanning her résumé. “Coffee shop. Retail. Pet store.”

“Eclectic,” Blair offered, trying to stand like a person who didn’t mind being barefoot in a boardroom. “But useful.”

He looked up at that. “Useful how?”

“The coffee shop taught me how to keep my charm before nine a.m.,” she said. “Retail taught me patience, especially when customers insisted a size six was actually a size two. And the pet store taught me how to calm anxious creatures.” She held his gaze. “That last one might be transferable.”

The corner of his mouth ticked. “Why should I hire someone without corporate experience?”

“Because experience is a thing you can acquire,” she said. “Attitude is not. And I have a lot of the latter. Also, I’m cheap, which I realize you’re not supposed to say in an interview, but we’ve established I’m having an unconventional morning.”

“You’re barefoot.”

“Yes,” Blair said. “And still here.”

Silence. Derek flipped her résumé shut, studied her for a long, unhurried moment the way you study a painting until you decide whether the chaos will grow on you.

“Ms. Evans,” he said finally, “you’ll hear from us.”

“By ‘us’ do you mean you, who broke my shoe, or HR?” she wanted to say. Instead: “Thank you for the opportunity.”

She left the glass room with dignity and two shoes in her bag. The blonde in the waiting room smirked as she sat. Ten minutes later, Blair walked back into the lobby, tried not to glance at the receptionist’s shoes, held the door for an older man with a cane—and her phone rang.

“This is Sarah from ZNK,” said a warm voice. “We have an offer. Can you start Monday?”

Blair blinked. “I—yes. I can start Monday.”

She hung up and made a sound like someone who had nearly drowned inhaling air.

Monday punched her in the face with enthusiasm. She got lost twice, greeted a mirror thinking it was a person, and discovered her cubicle was a neat rectangle outside Derek’s door. The name plate read DEREK CRAWFORD, CEO in the kind of font you don’t get to pick.

Emily from HR introduced her to a phone system that had more buttons than Blair felt one device required. Emily had motherliness and a tight bun and a way of talking that made you want to forgive yourself for not knowing where supplies lived.

“Mr. Crawford values punctuality and discretion,” Emily said. “And efficiency.”

“I value those too,” Blair said, hoping she could fake two of them while she built the third.

By ten she’d answered the phone, filed two reports incorrectly, learned the names of six executive assistants, and created a wind tunnel for Derek with a fan when the AC hiccupped. The fan hack earned her a grin from Jake in Marketing and a raised eyebrow from Derrick’s second-in-command. The phone rang again.

“ZNK—Blair speaking,” she said, then winced. “ZNK executive offices. How may I direct your call?”

The day tried to teach her she didn’t belong; she kept telling it she was staying anyway.

At noon, New People Protocol kicked in. The friendly ones from Marketing came by to meet “the barefoot girl.” The ones who wanted to be friendly with the CEO came by to measure. Rebecca Hartwell came by to judge.

She wore a red blazer the exact red of a stop sign and moved like she’d taught herself not to apologize for taking up space. Her smile was fine porcelain—smooth, cool, and likely to chip you if you handled it wrong.

“So you’re the new legend,” she said. “I’m Rebecca. Senior manager. I’ve been here eight years.”

“Blair,” Blair said. “Been here eight hours.”

Rebecca tilted her head. “Interesting that Mr. Crawford would place someone with such an…innovative interviewing approach just outside his door.”

“Maybe he wanted someone who could improvise,” Blair said, keeping her tone light. “Improvisation is useful when elevators break, coffee machines revolt, or finance decides to speak in riddles.”

“Boldness without substance is just noise,” Rebecca said. “We prefer quiet competence here.”

Blair smiled. “I can be both.”

They stared at each other a beat too long. Derek opened his door at that moment, saw them, saw the tension, and set a folder on Blair’s desk.

“Review before two,” he said. He glanced at Rebecca. “You and I at three.”

As soon as his door clicked, Rebecca leaned in and whispered, “Careful, dear. The higher you start, the harder you fall.”

Blair imagined tripping in front of the entire board and said, “I’ve already fallen barefoot in front of everyone. It’s the most freeing thing that’s ever happened to me.”

Rebecca left. Blair exhaled. The phone rang.

That afternoon, two things solidified at the same time: the rumor that the CEO had a new favorite, and Blair’s ability to become competent on pure adrenaline. She memorized Derek’s calendar, the difference between a board brief and a board book, the way he took his coffee (black, criminally black), and the fact that ZNK had a client named Hamilton & Associates who were threatening to walk.

At 4:12 p.m. the elevator groaned and hiccupped and trapped Blair inside with Derek between the tenth and ninth floors. “Of course,” she said to the universe. “Of course we’re now doing this.”

“You’re remarkably calm,” Derek observed, pressing the emergency button.

“It’s my thing,” Blair said. “Too broke for therapy. Developed a sense of humor instead.”

“Does it help?”

“I’m not crying in an elevator,” Blair said. “So, yes.”

The elevator lurched, then settled. For a moment the two of them leaned against opposite walls and shared air. Blair realized how long it had been since she’d stood still long enough to hear her own heartbeat. Derek looked at her as if she’d said something at once obvious and new.

“You’re not like anyone I’ve worked with,” he said.

“Is that a compliment or HR paperwork?” Blair shot back.

He laughed, and the sound startled both of them. When the elevator began moving again and spilled them onto the lobby like a re-released secret, Blair carried a ridiculous sense of victory into her evening: she was still here, and the building hadn’t eaten her.

What the building did do, three days later, was try to swallow her on purpose.

“Derek asked you to present the Harrison numbers this afternoon,” Sarah from HR said, appearing at Blair’s desk like a messenger dove with a hand grenade. “Board room at two.”

Blair smiled the smile of a person who is almost certain she is about to die and prefers to do it while standing. “Of course.”

She spent the next 120 minutes converting fear into determination. At two, she stood in front of a table full of suits and chose the only weapon she trusted: honesty.

“Two hours ago,” she began, “I thought Harrison was a Harrison Ford film. It’s not. It’s Western Division quarterly sales. Here’s what I learned: we started the year sprinting, face-planted in Q2, and have been jogging uphill ever since. That’s not sexy. But it’s promising.”

Robert, Director of Sales, raised a skeptical brow. “And why the Q3 climb?”

“Because marketing finally found the right audience at the right time with the right price,” Blair said. “Because our competitors had supply issues and we didn’t. Because sometimes the answer isn’t a magic trick, it’s not making the same mistake twice.”

Silence. Then Robert started clapping, the way men clap when their egos aren’t in the way. The room followed. Derek’s expression didn’t change much, but his eyes warmed.

By five, “barefoot girl” had become “the assistant who saved Hamilton,” and gossip had come with a new accusation—she’d saved it because the CEO held her hand through it.

On Friday, Derek found her in the elevator and said, “The annual gala is Saturday. I’d like you there. As my date.”

Blair felt her bones clang with warning and want. “You realize that’s gasoline on a rumor bonfire.”

“Let’s stop pretending there isn’t a fire,” he said.

She wore a simple black dress she’d bought for an aunt’s funeral; Derek wore a tux that made him look like the bad decision in a romance novel. Half the room stared like they were witnessing a scandal; the other half stared like entertainment was finally here.

Right as Margaret from Marketing’s husband asked Blair how she knew which fork to use, the heel of Blair’s shoe surrendered to physics. It snapped audibly. She stood with dignity while her ankle performed a tragic ballet.

There are two kinds of rooms: ones that punish imperfection, and ones that become human when something real happens. This one converted in a heartbeat. “That happened to me at our wedding,” Margaret said cheerfully. Someone handed Blair a chair. Someone else handed her a drink. Derek leaned in and whispered, “Emergency kit?”

“Very funny,” Blair said. She kicked both shoes off beneath the table and finished dinner like a woman who had been preparing for that moment her whole life.

They danced afterward. Dance is a generous word here. Derek was better than he’d claimed; Blair was worse. She apologized twice, laughed three times, and eventually gave up on steps altogether. He held her and swayed while the dance floor, and then the room, and then the world, got smaller. At the end of the night in a quiet parking lot, he touched her cheek as if he wasn’t used to being allowed and kissed her like he’d been waiting since the elevator.

After, they stood forehead to forehead breathing the same air.

“This changes everything,” she whispered.

“I know,” he said.

What neither of them knew was that change had a name: Rebecca.

She had been watching for weeks. Professional jealousy curdled into personal vendetta in tiny increments. She followed them discreetly, collected photographs no one had authorized, waited until the worst possible morning, and mailed them in a brown envelope addressed to the board.

On Tuesday at 10:30 a.m., Sarah from HR asked Blair to step into a small conference room where the board chair and vice chair sat like two judges you didn’t get to choose.

“An inappropriate relationship with Mr. Crawford has come to light,” said Charles, Chairman, sliding a glossy print across the table. Derek’s hand on Blair’s cheek. Her eyes closed. It didn’t matter that the moment had felt like safety. On paper it looked like grounds.

Blair swallowed. “My relationship is not company property.”

“It becomes our property when it affects perception of fairness,” Patricia said crisply. “We must protect the company from legal risk.”

“From love?” Blair said, no longer bothering to charm them. “Or from a narrative you can’t control?”

The door opened. Derek stepped in, took in the scene at a glance, and said in a voice that didn’t often get used, “My office. Now.”

“Sit down, Derek,” said Charles.

“No,” Derek said, looking at the photo. “Where did you get this?”

“It doesn’t matter,” Patricia replied.

“It matters enough to cost someone their job,” Derek said. He turned to Blair. “Do you want to resign?”

“No,” she said. “Do you?”

He looked at the board. “If she goes, I go.”

It wasn’t a bluff; it was a line. Later, he fired Rebecca not for the relationship (you can’t police hearts) but for violating privacy and undermining leadership with malice disguised as concern. The board grumbled, then relented. Gossip didn’t. Within two days the entire company had a different kind of photo to share: Derek on one knee in the park.

Blair didn’t see it, because she had left a note on his desk—I need time to think—and walked back to the only place that had ever made her feel solid: the community center in Ballard where story hour on Tuesdays could fix almost anything.

“Polite dragons knock,” she told a half circle of kids. “They use their words.”

Outside the room, Derek watched until the story ended and the kids ran for apples. He stood in the doorway like a man who had learned weight distribution in high school wrestling and never needed it again until now.

“What are you doing here?” Blair asked.

“Remembering,” he said.

“What?”

“That life can be simple. That yes and no can be complete sentences.” He sat in a blue plastic chair far too small for him; she sat in a red one whose legs squeaked. He told her the board was calmer. He told her Rebecca was gone. He told her he didn’t want to run this company if it meant being the kind of man who hid in his office instead of loving someone with a whole heart.

“Your job—” she began.

“Isn’t my life,” he finished.

He took her to Green Lake, down to the water where the ducks paddled on like ancient witnesses. He knelt on the grass and looked up at her with no marble left in him at all.

“I’d rather be ridiculous with you than rational without you,” he said, and Blair laughed because of course she would end up proposed to by a man kneeling in a puddle of duck prints.

“You’ve lost your mind,” she said, tears already blurring the world.

“Yes,” he agreed. “On purpose.”

“Then yes,” she said, and kissed him while someone on a bench clapped and a little boy shouted, “Hey! Are you getting married?”

“Apparently,” Derek told him.

Footnote: Life did not end there. It began again.

Part Two

Six months later, Blair stood at the edge of a white tent on Alki Beach with damp sand under her toes and a bouquet of wildflowers in her hands.

“I’m about to get married barefoot—again,” she told Emma, her maid of honor, who had flown up from Portland and had the unearned serenity of a person not about to vow anything in front of dozens of people. “This is now my brand.”

“Lean into it,” Emma said, fixing Blair’s hair with two bobby pins and a grin. “You’re a barefoot bride. The universe foreshadowed you.”

A determined, flower-crowned woman in her seventies bustled up. “If he forgets the vows, we’re not returning the gift, you hear?” said Mrs. Rossetti, Blair’s neighbor and self-appointed wedding consultant.

“I wouldn’t dream of it,” Blair said, kissing her cheek.

Under the tent, ZNK folks mingled with community center families and a few kids who’d been bribed with cupcakes to sit still. The board chair came, shook Derek’s hand, and whispered, “She makes you better.” He nodded, forgetting to be wary in public for once.

The music began. Derek stood at the arch on the sand, his tux a smart compromise between “I am a CEO” and “I will get seagull poop on this.” When Blair stepped out, her dress caught the light, and then every other part of her stole it.

She walked down the aisle barefoot. It felt right. She belonged to ground that way.

“Ready?” he whispered when she reached him.

“I think I have been,” she whispered back.

He vowed to keep his calendar open on Sundays and to stop eating cereal out of the mixing bowl; she vowed to always laugh first at herself and to keep copious bandaids in every drawer because life is pointy. When it was time for rings, they exchanged simple bands—the inside of Blair’s engraved with Chaos Coordinator, Derek’s with Recovering Robot. The efficient pronounced them married; the ocean did not swallow them; the ducks approved.

At the reception, Charles Morrison came over, contrite and sincere. “I should’ve trusted you both sooner,” he said. “Turns out profit goes up when leaders act like people.”

“Write that down,” Blair said. “Put it on mugs.”

Emma led a toast that should have been a roast but blurred into both. Jake danced with Margaret. Emily wept into a napkin like a favorite aunt. A little girl from story hour hugged Blair’s dress and asked if there would be dragons at the honeymoon. Blair knelt to whisper, “Only the polite ones.”

When the sun dipped and the wind cooled, Blair and Derek stood at the edge of the deck and watched light smear pink across the water. Derek turned to say something about how vows are easier than practice, but Blair spoke first.

“By the way,” she said, voice bubbling, “our honeymoon will be educational.”

“How so?” Derek asked. “Will I finally learn how to load your dishwasher the right way?”

“As in you’re going to learn how to swaddle a baby,” she said. “We’re having one.”

He lifted her and spun her and laughed like the first time. “Are you sure?” he asked into her hair.

“Eight months sure,” she said. “Give or take.”

He breathed out like a man who had been bracing against a storm only to discover the thunder was applause. “Then okay,” he said. “Okay.”

Rivera & Crawford (she rolled her eyes affectionately every time someone said and Crawford) didn’t just do well; it did good. They invested in a vertical farm that fed three neighborhoods. They funded a startup that turned plastic into bricks. They underwrote a program making laptops out of recycled parts for teens who thought school was for other people. They picked deals where spreadsheets and souls aligned—choices that made some investors roll their eyes and others double their checks.

Blair learned to read term sheets and to trust her gut. Derek learned to make soup without burning it and to ask for help before evenings fell on him like bricks. They fought once about payroll and twice about a couch and were equally wrong each time in ways that made them right by morning. Blair swore more than once that if she ever had to explain “runway” to a startup whose only plan was slogans, she would move to a desert and sell ice. Derek told her she was not allowed to move to a desert while pregnant, and she told him he didn’t get to decide which deserts she explored. They laughed and did not move.

They made the cover of a magazine in matching blazers which they immediately regretted, and then Blair insisted they never pose with arms crossed again because “we’re not pretending to be a bank vault.” They built a culture where saying “I don’t know” earned you help instead of humiliation and where “family leave” meant what it implied. People stayed. People thrived. People used words like belong in exit interviews they didn’t want to give.

One afternoon, six months after the wedding, they were invited back to ZNK to speak. Blair stood on the stage she’d once nearly run off and told the story of her first board presentation. She did the Harrison Ford joke again. It landed. She talked about barefoot mornings and broken heels and how sometimes your place finds you more than you find it. She didn’t mention Rebecca by name, but she did say, “Women aren’t each other’s obstacles. Systems are. And we can fix systems.” The applause sounded like relief.

Afterward, an intern with a trembling voice said, “I almost didn’t apply. I didn’t think I looked like someone who should be in a place like this.”

Blair looked at the intern’s shoes—sensible flats—and smiled. “I showed up barefoot,” she said. “You’re already ahead of me.”

When their daughter arrived with a wail that sounded exactly like a protest and a grin that arrived the next day like grace, Derek cried without embarrassment and without apology. He bought two dozen tiny socks, none of which the baby kept on. Blair laughed and said, “Of course. She’s my child. She’s allergic to shoes.”

At home, on a simple shelf near the front door, between a row of children’s books and a jar of spare keys, Blair kept three things:

The broken heel from that first morning, mounted like a museum display with a handwritten label: Proof of concept.

The brown envelope’s anonymous note that had said I know your little secret, now scribbled over with a better truth in bright marker: Everyone does. We celebrated it on the beach.

A framed copy of the email Derek had once written and never sent, the one that ended with You asked me to be honest. I’m in love with you. She’d circled that last line and added beneath it, in her handwriting: Me too, in case you ever forget.

On Saturday mornings they walked to the farmer’s market with a stroller and no agenda. Sometimes success is the ability to buy raspberries without counting; sometimes it’s knowing which vendor lets your kid sample everything with sticky approval. Blair taught their daughter to wave at dogs and to say “please” and “thank you” louder than “mine.” Derek taught her to knock politely—on doors, on hearts.

“What shall we teach her last?” he asked one evening, when the baby was asleep and the house was a small planet of quiet.

“That barefoot is a way to begin,” Blair said. “Not a reason to stop.”

Derek nodded. “And that being chosen once doesn’t matter as much as choosing yourself every day.”

They clinked glasses—hers ginger ale, his the expensive sparkling water he pretended was interesting—and turned on an old movie. Blair put her feet up on the couch and sighed contentment.

“You know,” she said, “if there’s a moral, it’s probably this: come as you are. The rest can be learned.”

“And: don’t stare at a person’s feet when they walk into an interview,” Derek added.

“That too,” she said. “Unless you need a good story to tell later.”

They laughed, and the baby stirred in the next room, and the ocean didn’t crash because there was no ocean, just a city sleeping and a family not taking that for granted.

The week Blair returned to work after maternity leave, Rivera & Crawford funded three new projects, Derek started scheduling “no agenda” one-on-ones so people could tell him the truth without a slide deck, and Blair built an in-house program to help entry-level hires learn the unwritten rules she’d never had. She named it Barefoot Beginnings and made everyone who taught in it take off their shoes at the front of the classroom.

“Why?” someone asked.

“So you remember,” she said, “that comfort is a privilege you’re obligated to extend, not a wall you get to hide behind.”

They did. The company’s ROI stayed luminous. The notes from founders stayed better. The stories of lives changed stacked higher than any trophy.

On the anniversary of her interview, Blair took a walk to the ZNK building alone. She stood across the street and looked up at the mirrored facade, at the reflective curve where city and sky met.

A young woman in an inexpensive blazer hurried past her, almost tripping over a crack in the sidewalk.

“Hey,” Blair called. “Good luck.”

The woman turned, harried and grateful. “Thanks,” she said. “I’m interviewing.”

Blair pointed at the woman’s feet, at the scuffed flats. “Those are perfect,” she said, and the woman laughed like a person who hadn’t known she needed permission to be exactly who she was.

Blair watched her disappear through the revolving doors like a future. She breathed in, breathed out, and kept walking toward home, toward a life that still startled her with its warmth.

Sometimes the most powerful decision you make is to show up with what you’ve got, not wait until it looks like what the world told you it should. Sometimes a snapped heel is a plot twist. Sometimes a CEO learns how to be human from the person who joked about dying in an elevator. Sometimes the girl in bare feet becomes the woman people hire to teach them how to walk.

And sometimes the happy ending isn’t a period at all. It’s a sentence you get to keep writing—with messy margins, crossed-out words, and feet firmly on the ground.

END!

News

POOR SECRETARY RENTS A BOYFRIEND FOR $500—HE’S A MILLIONAIRE CEO WHO CHANGES HER LIFE… ch2

POOR SECRETARY RENTS A BOYFRIEND FOR $500—HE’S A MILLIONAIRE CEO WHO CHANGES HER LIFE… Part One Elena Rivera typed…

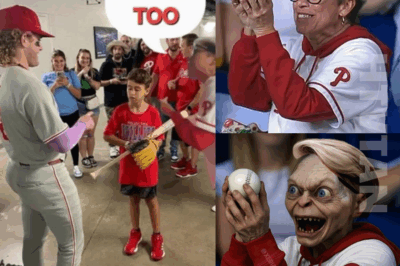

Phillies “Karen” Faces BRUTAL Fallout After Viral Ball Snatch

From stadium BOOS to online SHAME and RUMORS of job loss, the woman branded a “Karen Hall of Fame” member…

My Parents Said, My Sister’s Wedding Day, It’s Better I Not Be There So, I Vanished… ch2

My Parents Said, “My Sister’s Wedding Day, It’s Better I Not Be There.” So, I Vanished… Part One The…

“You’ll Get the Ball Back, But Not Where You’d Like It to Be” — Whoopi Goldberg Slams ‘Phillies Karen’ After Viral Ballpark Drama

A Phillies fan branded “Phillies Karen” sparked national outrage after being caught on camera taking a home run ball from…

Phillies ‘Karen’ is facing the WORST backlash ever fans are NOT holding back…Should this be stopped?

Phillies “Karen” Faces Brutal Fallout: Viral Shame, Job Rumors, and a Stadium Exit From Outrage to Redemption: The Aftermath…

My Mother Told Me I Couldn’t Afford Dad’s Birthday Dinner — Then The Staff Greeted Me As The Owner.. ch2

My Mother Told Me I Couldn’t Afford Dad’s Birthday Dinner — Then The Staff Greeted Me As The Owner …

End of content

No more pages to load