Part 1

I needed to go for a walk that day. It didn’t matter that I’d been exhausted the day before, didn’t matter that I was supposed to have a friend over in a few hours. A single idea had settled in my head like a coin at the bottom of a fountain and the water wouldn’t stop rippling around it.

“Lincoln Avenue.”

Just two words. A plain, forgettable name you could find in almost any town in the country. But when I woke up that morning I couldn’t think of anything else. Lincoln Avenue. The syllables pulsed like a second heartbeat. I tried to swallow them. I tried to pretend it was nothing. But pretending is how people die.

Like always, part of me wanted to ignore it—ignore the street name, ignore the Voice that, for now, was saying it gently, as if it lived at the back of my own thoughts and only wanted to help. If it were just about me, I would have ignored it. Please believe me when I say that. It wasn’t just about me, though.

Two weeks earlier my dad had been in the hospital for a head injury. My sister Cathy called me the moment it happened.

“Dude, you need to get to Flower Hospital now!”

“Why? Finally decided to get that stick out of your—?”

“Just shut up and listen! Dad fell and hit his head—must have been working on the roof or something.”

“What? I thought he was getting contractors for that.”

“Well apparently not, Dan! Get to the hospital now. They’re taking him to the ER.”

If past events were any indication, my dad’s life depended entirely on what I did within the next twenty-four hours. I’d be lying if I said he and I were close even before the incident, and we sure weren’t in the last five years since I moved out. I’m sure he resented me for leaving, at least as much as I resented him for shutting down. Aside from the past few months, we barely made any effort to repair anything. We were trying, awkwardly, slowly—two people who’d forgotten how to stand in the same room without bracing for an impact that already happened.

He’s the only parent I have left. We’d just started to love each other again. I needed him. More than that, Cathy needed him. They’d been each other’s rock since Mom died, and I knew how badly it broke all of us when she went. I couldn’t afford to let it happen again.

Outside, the weather was the kind of day people post about—blue as a washed dish, sun warm without being mean, a small breeze as polite as a store greeter. It felt insulting, considering what was about to happen. As soon as I stepped past the edge of my yard and the sidewalk accepted me, the confirmation came, soft and savoring: the Voice whispering the street again.

“Lincoln Avenue.”

A mile in, my phone rang. I didn’t need to look to know it would be Cathy calling for the hundredth time with some update on Dad’s condition. I didn’t answer. I couldn’t stand another version of we’re not sure yet or the room went quiet for a minute and I thought— The clock was already ticking. Watching the hands wouldn’t stop them.

It wasn’t a straight shot. It never is. At certain intersections the Voice spoke again, giving me small, unremarkable instructions a stranger might call intuition.

“Right. Left. Right. Straight.”

Routes I’d driven in minutes stretched into a slow, barefoot kind of time. My feet learned the town’s uneven sidewalk slabs by heart. A familiar strip of restaurants and gas stations rose around me. Cars shook by. Joggers bobbed past. A kid on a scooter scraped to a stop and watched me like an anthropologist, then flew off again. None of them had any idea they were inside a story that always ended the same way. Out of habit I checked my steps app. A little over three miles. An hour and change. I wondered how much farther I had to go.

Not long, it turned out. I started hunting every green sign at the corners, teaching my eyes to snap to the white block letters. Two hours in, just past a tired-looking apartment complex, I found it. The small green sign said, in weather-chopped lettering:

LINCOLN AVENUE.

My chest tightened like I’d just gone underwater. Doubts returned like polite guests. Was I really doing this again? What if I was wrong? What if I was having a waking nightmare? I hadn’t slept much since Dad was admitted. I’d read that after twenty-four hours without sleep the mind starts coming apart, after forty-eight you can hallucinate. You can survive on four hours here and there, the article said, but the debt collects interest. Maybe that’s all this was—a hallucination with shoes on.

“209 Lincoln Avenue. Red roses.”

The Voice was back, and the little illusion I’d made for myself folded like a paper napkin. I could justify hearing a common street name; common names are everywhere. But this was precise—an address, and a marker to make sure I would find it. I wanted to believe I was sick, that my brain had made a ghost and then hired it to haunt me. I really did. But I also remembered every other time. I remembered the one time I refused. I remembered Mom. The image lives where my language can’t go. Shattered is the closest word and it is wrong.

Lincoln Avenue itself was a Norman Rockwell painting without the guilt. Rows of houses, small intersections, mixed lawns—some clipped, some defiantly wild. A few trees standing around like elderly chaperones. The skies above were polite. I could hear birds I couldn’t see. If I hadn’t known better, I might have stopped to enjoy a walk like any other. I did know better. I had work to do.

I try to be unremarkable when I do this. A stranger out for steps. A face your brain doesn’t bother to save. Indifference is the best gift anyone can give me, though I don’t deserve it.

Most houses were the same: one, maybe two stories; driveways that told you how many salaries lived inside; small flower beds rehearsing the seasons in color. The neighborhood wasn’t rich, but it wasn’t hurting. People mowed and edged and knelt in dirt. Kids ran and screeched. A dad threw a ball too high and laughed when his daughter glared at him for it. Adults waved at me, and I waved back because refusing to wave at a man’s wave when you’ve come to help hurt his street feels like leaving a debt unpaid.

Safe, I thought. This is supposed to be safe.

I’ve stopped trying to say the Voice did this, not me. The grammar doesn’t hold. I made the choice. I walked the walk. I met the eyes and spoke the words. I have reasons, but reasons are not a defense at the end of anything. The only sentence that matters is that I did it. I told myself Dad was worth it. I told myself Cathy was worth it. I told myself the thing I never say out loud: that I have already priced my life low enough to spend it like this.

Addresses slid under my eyes:

199: pink lilies.

201: blue hydrangeas.

203: white orchids.

205: red spider lilies.

207: black roses.

209 came and looked like home. Fresh paint. The kind of flower bed you get when somebody’s fingers know dirt. Red roses with their necks lifted like they could feel the sun personally noticing them. Chalk drawings in the driveway—two tall stick people and a small one between them, all smiling those wide, impossible chalk grins. At the end of the street, a small guardrail held back a little scrim of woods; through the cracks I could see a field opening its throat to the sky.

My heart dropped so fast my legs felt hollow. I took in the siding, the numbers, the mailbox flag, like I could memorize it and then time would be kind and rewrite what happens next because I paid attention. I didn’t want to do this.

I had to do this.

I couldn’t do this.

I had to do this.

“Hey, buddy? Can I help you?”

Not the Voice. Real. Off to my right. I turned and met a man about mid-thirties, maybe ten years older than me. Short black hair, beard neat without being vain. Plain white T-shirt. A paper grocery bag in the crook of his left arm, the kind that creases a brown line in your skin. His posture said tired but kind. His eyes said this is my house and I will be polite to you until you give me a reason not to be.

“Restaurant. Do it,” the Voice said, half instructing, half delighted. The tone was different now. Gone was the whisper. This was eager. Childlike. I recognized it. I wanted to be sick.

“Oh—hey,” I said. I let confusion into my face, a soft fog. I glanced from the house to him and back, a little embarrassed. “I think I got turned around somewhere. I’m looking for that new steakhouse that moved in a few weeks ago?”

He let out a small chuckle and shifted the bag to his hip. “Lincoln’s Steakhouse?” I nodded like a good student.

“Yeah, you’re not the first to wind up here.” He tilted his head toward my pocket. “You got a phone on you?”

Every bone in my body told me to turn and run, but my hand obeyed the script. I pulled my phone out, unlocked it, opened the GPS, handed it to him. He typed an address quickly, muscle memory in his thumb. I watched his fingers as if I could memorize something besides the shape of doom in a man’s hands. The Voice’s anticipation pressed at the back of my eyes like a headache about to bloom.

He handed the phone back. “There you go. Should be good now.”

I faked a laugh and rubbed the back of my neck. “Sorry about that. Didn’t mean to intrude.”

“You’re like the third guy that’s happened to this month,” he said, waving it off. “No big deal.”

His guard had lowered that infinitesimal amount people lower it when they decide you’re safe enough to finish a conversation with. It was time.

“Dan,” I said, and held out my hand. It was the first of two true things I would tell him.

He looked at my hand, amused at the formality, then sighed a little and shifted his bag to take it.

“Chuck,” he said.

Of course that was his name. My father’s name. I felt, absurdly, a desire to ask him his middle name, whether he liked his coffee hot or iced, whether he mowed his own lawn for the thinking time or just because paying someone felt like giving up. I wanted to ask if he had a son who rolled his eyes at him, a daughter who stuck her tongue out when he told a joke. How closely did our families rhyme?

When I released his hand, something released inside my skull. Like a blocked sinus opening, pressure rushing out. The Voice went quiet the way a power plant goes quiet during a blackout—sudden, absolute. It was finished. The charge had moved. The path had been made. I was a wire cooling in a wall.

“I hope you have a good rest of your day,” I said, and meant it. It was the second true thing.

He gave a polite half-salute with the fingers not strained by the grocery bag and headed up the walk. I didn’t watch him go in. I didn’t watch the door close. I didn’t stand around to see what would happen. There are lines even I won’t cross, and I don’t know if that makes me a coward or a connoisseur of my own particular misery.

The walk home was longer, heavier. Rational me would say I’d already gone five miles and now I was paying the tab. Guilty me would say the weight was the habit settling around my shoulders again, the one I had promised myself to quit a hundred times since the Voice attached itself to me in that stupid childhood game fourteen years ago. The truth is probably both, plus the hollow echo of silence where the Voice had been. You don’t realize how loud a thing is until it stops.

For half a block I let myself hope. Maybe this was it. Maybe the Voice would stay gone. Maybe Chuck would be the last one. Maybe Dad’s recovery would be the final transaction in a file stamped CLOSED. I have said maybe to a thousand doors and all of them opened into the same room. The Voice always comes back.

It came back as soon as I opened my front door. Not words. Not even a feeling. A pressure. A shadow laying down inside my head and making itself comfortable.

I slammed the door and leaned my back against it, palms flat to the wood like the hinges were a living thing I could hold in place. The Voice didn’t speak. It fed.

Crunching. Ripping. Snapping. The sounds came from nowhere and everywhere. It’s always like that—like the house is a shell and something is chewing the ocean on the other side. Phantom pains flared in my arms, my ribs, my thigh. Never a mirror of anything real. Just enough to be a language I could almost understand. The Voice made small, satisfied noises, an animal set loose in a butcher shop. It didn’t know I could hear, or it did and didn’t care. I pictured a little boy I had never met. A wife I would never know. Chalk dust on the knees of someone’s jeans. Tears blurred the lines of my living room. Pops came next. Then a thin peal of giddy laughter, which is as close as I will get to describing a sound I wouldn’t wish on anyone still trying to be alive. Even now I hope they’re already dead when this part happens. I hope that for my mother most of all. There’s only so much a mind can hold without spilling the rest of you out on the floor.

I don’t know how long I sat there, curled by the door, rocking myself like a metronome that refused to keep time. The sounds stopped. I didn’t move. Daylight ran out. House lights didn’t come on. The dark folded over me like a blanket that remembered my weight. I must have gotten up at some point because the next thing I remember is waking in my own bed with the blinds open to a night so black it felt like a judgment.

My phone lit my face with Cathy’s name. I answered. I can fake surprise. It’s one of the only skills I keep sharp. She told me Dad was improving. Lucid. Talking. He had asked for me. Like clockwork, the Voice had kept its deal. It always does. That’s the point.

We talked for a few minutes. I told her to get some sleep. I meant that, too. Then the quiet was back and it didn’t feel like rest. I wanted to sleep. Sleep would saw the edges off. Sleep would give me a few hours without the shape of my own hands in the story. Instead I opened my browser and typed in my local news station. I don’t know why I do this every time. It’s not like I don’t know what I’ll find. Maybe it’s my penance: forcing myself to read the name they write, the photograph they choose.

The page loaded and I didn’t have to scroll.

LOCAL MAN FOUND EVISCERATED IN HIS HOME. SUSPECT CURRENTLY UNKNOWN.

The headline sat there like it was waiting for me to admit it existed. I stared at the screen until the pixels blurred and resolved, blurred and resolved, like breathing. I tried to imagine a version of the future where this headline doesn’t arrive. There isn’t one. Not yet.

I set the phone face down and lay there in the dark, counting the cracks in the ceiling by memory, telling myself I would go see Dad in the morning, telling myself I would bring him coffee, telling myself I would look him in the eyes and let that be enough good to balance the scale even for a second. The scale doesn’t care about seconds.

In the corner of the room, the dark felt heavier than it should. The Voice didn’t speak. It never does after. It sleeps like a cat with blood on its whiskers, full and twitching.

I closed my eyes and told myself, again, the biggest lie I know how to tell: that this was the last time.

—End of Part 1.

A Local Man Was Found Dead Yesterday. It’s My Fault.

Part 2 of 2 — Conclusion

The lie didn’t even make it through the night.

By morning, the Voice was back.

Not with words, at first—never with words at first. It was a weight behind my eyes, a strange alertness that didn’t belong to me, like something else had woken up in my body and was stretching into the corners. I lay still and listened to the quiet in the house. When the Voice is here, even silence feels different—too deep, like water waiting for you to slip.

I’d barely set foot in the kitchen before it spoke.

“Elm Street.”

Just like that. Two words. Another coin tossed into the fountain. My chest tightened.

“No,” I said out loud, like it would make any difference. “Not again.”

The Voice didn’t respond. It never argues; it just waits. The waiting is worse than the whisper.

I tried to keep moving through my morning—coffee, shower, phone in hand. Cathy had texted another update: Dad says he feels good enough to go home next week. The words should have lifted me. They didn’t. Not when I knew the bill was already in the mail.

I told myself I wouldn’t leave the house. I’d stay put. Ignore it. But ignoring the Voice is like ignoring a ticking you know is a bomb—you hear it louder the more you try not to. By noon my skin felt too tight, and the walls were leaning in, and my coffee had gone cold in my hand while I stood at the window, staring at nothing.

“Elm Street. 318. Yellow tulips.”

Now it was an address. The marker, like last time. That second heartbeat again, only stronger.

I wanted to scream. I wanted to call Cathy, tell her everything—the game, the Voice, the people. The rules. But I’d tried once before, years ago, with someone I thought might believe me. They didn’t. It’s hard to blame them; it sounds insane. And when the Voice decides you’ve broken the rules, it doesn’t care if the person you told lives or dies.

I don’t know if it would take Cathy. I’m not going to find out.

By 12:30 I was walking.

The route this time was mercifully short—less than an hour, even with the small detours the Voice fed me. Left here, right there, cross now. It has a way of keeping me in motion, as if the world’s whole street grid is a board and I’m its piece.

Elm Street was a strip of mid-century homes—modest, but lived in. Curtains drawn back to let light in, kids’ bikes toppled in driveways, a smell of fresh-cut grass sharp enough to taste. I scanned the house numbers like I was looking for a friend’s place.

314: irises.

316: carnations.

318: yellow tulips, bright against fresh mulch.

I stopped at the curb. The house was two stories, pale blue siding, white trim, a porch swing that moved just slightly in the breeze. Through the front window I could see the top of someone’s head moving past—a woman, maybe.

The Voice was silent now. It always is when I arrive. It knows I know the script.

My hands curled into fists. I thought about walking past, pretending I’d gone too far, that I was looking for someone else. I thought about turning around.

But I also thought about Dad.

He was on the porch before I could decide. Mid-forties, maybe, hair starting to go silver at the temples, wearing jeans and a polo shirt with the collar turned down. In one hand, a coffee mug; in the other, a paperback book. He looked at me with the wary friendliness people reserve for strangers in their neighborhood.

“Hey there,” he said. “Need a hand?”

I swallowed. “Yeah, actually. I’m looking for, uh… the hardware store? My GPS crapped out on me.”

He grinned faintly. “Oh, sure. You’re not far. You got your phone?”

I handed it over. I could feel the clock ticking in the back of my skull. He thumbed in an address, handed it back.

“There you go.”

“Thanks,” I said. And then, because this is how it works: “I’m Dan.”

He shifted his mug to shake my hand. “Mark.”

The instant our palms met, the pressure in my head broke. A dam giving way. The Voice was gone. The game was over—for me, for now.

“Appreciate it,” I said, stepping back.

“No problem,” he said, already turning toward his door.

I didn’t look back.

The walk home was a tunnel I didn’t want to reach the end of. Every step was a countdown. When I finally closed my own door behind me, the sounds started almost immediately.

The wet tearing, the crunch of something giving way. My stomach flipped and I pressed my palms to my ears, but it doesn’t matter. The sounds aren’t in the air—they’re in me. Phantom aches in my ribs, a sharp twist in my knee, a heat blooming behind my eyes.

The Voice was feasting.

I curled on the couch until it stopped.

Night came without me noticing. I sat in the dark, phone facedown on the table beside me, until it buzzed. Cathy, again. Dad’s numbers were good. The doctors were optimistic.

And all I could think about was Mark’s porch swing, still moving slightly when I left.

I didn’t check the news until after midnight.

LOCAL MAN FOUND DEAD IN APPARENT HOME INVASION. NO SUSPECTS.

No names yet. They never print the name right away. But I already knew it.

I’ve thought a lot about the day the Voice first came to me. Fourteen years ago, in a friend’s basement. We’d been playing some dumb childhood ritual-game, the kind you find on early internet forums: a mix of dares and half-baked occult instructions. Candles, chalk, a mirror. You had to speak into the dark and “invite” a guide. I thought it was all theater.

But something answered.

The others laughed when I said I’d heard it whisper a street name. They thought I was making it up. But the next day, the local paper ran a story about a man found dead on that very street. I didn’t put it together until the second time. By the third, I knew the rules:

The Voice speaks, you follow. You make contact with the one it’s chosen. It feeds, and someone you love is spared—healed, protected, lifted out of harm’s way.

If you refuse, the Voice chooses from your circle instead.

I tested it once. Mom was gone within a week.

Now, I don’t test it.

I don’t bargain, I don’t plead. I walk. I find the street. I say my name. I shake the hand.

And every time, I tell myself it’s the last time. That Dad will be the last one I save. That I can learn to live with what I’ve already done and let the rest burn.

The Voice lets me think that—for a while.

Until it whispers another street.

And I lace my shoes.

And somewhere, someone’s porch swing moves in the breeze, waiting.

END!

News

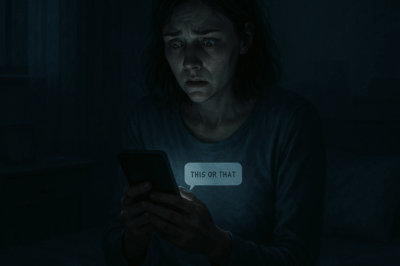

I keep getting texts from an unknown number asking “This or That”. Whichever I pick, something vanishes.

Part 1 Ding. I wasn’t even properly asleep—just suspended in that humming limbo where the news read itself to no…

My mother used to tell me that my father was an angel. I thought she was crazy until I saw him myself

Part 1 I don’t remember my mother ever being sane. From the day I was born, the house made a…

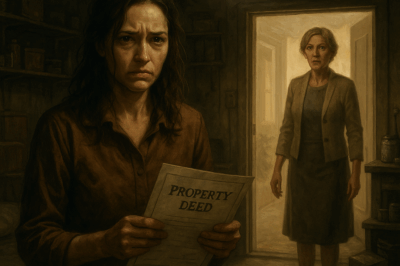

Stepmom Made Me Sleep in the Garage for 4 Years—Then Tried to Steal My “Dead” Dad’s Estate

Part 1 She thought she was playing a long game. She never realized I was silently keeping score. I’m Stephanie,…

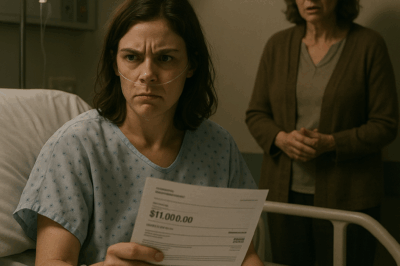

My Mom Took $11K While I Was in Surgery and Said It Was “For Family”

Part 1 Okay, here’s how it really started. Not with a bang, but with a rectangle of paper taped to…

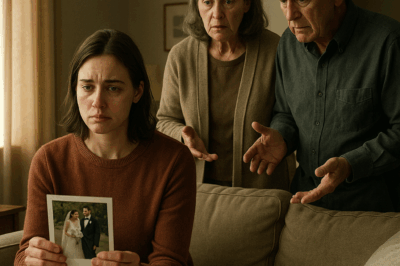

Parents Funded Brother’s Lavish Wedding, Then Begged Me For Help Years Later

Part 1 The courthouse steps felt cold under my bare legs that morning. I’d chosen a simple cream dress—nothing fancy,…

My wife has started dreaming about things I’ve done

Part 1 “You left the utensil drawer open this morning, didn’t you?” she asked, stepping out of our bedroom as…

End of content

No more pages to load