The Day My Stepfather Tried to Bury My Future Alive — and the Moment a Single Forbidden Document Dragged His Darkness Into the Light Before He Even Realized I Was Already Watching Him Bleed From His Own Lies…

I never expected that the quiet, almost suffocating tension inside my childhood home—the house that smelled permanently of polished wood, old legal folders, and the aftertaste of secrets—would one day crack open with the kind of force that could tear a family apart, or maybe reveal that the family had been rotting from the inside long before I learned how to recognize the difference between a warning and a wound, long before I understood that the man who married my mother was not just the kind of stepfather who monitored every expense or insisted on keeping receipts in color-coded drawers, but the kind who could hide an entire inheritance with a steady hand and an unblinking gaze, as if he believed the universe itself rewarded him for being clever enough to steal from a girl who hadn’t yet learned how dangerous hope could be.

And maybe I should have seen it sooner, because every conversation he had with me ended with the same thin smile, the same measured pause, the same tone that felt like a lock being turned from the other side of a door I couldn’t see, even when I could practically hear his mind calculating how much of my life he could rewrite without me noticing, how many pieces of my future he could pocket before I learned how to check the missing corners.

But I was young then, and I mistook silence for peace, obedience for safety, and the illusion of a father figure for something that could be trusted, not realizing that a man can tuck away sins the same way he tucks away documents—flat, pressed, hidden, and lethal only when someone finally lifts the lid.

By the time my mother got sick, the lines had already been drawn in invisible ink; he hovered over her hospital bed with the type of rehearsed grief that photographs well, the kind of performative devotion that makes nurses nod with sympathy, but when he turned toward me, his eyes were sharp enough to slice through my ribs, to remind me that whatever softness he showed her would never extend to me, not when money was involved, not when control was involved, not when the last barrier between him and my mother’s estate was slipping away one labored breath at a time.

I remember the night she passed as vividly as the texture of the blanket she held in her final hours, the one she used to wrap around us during winter storms; I remember the way her fingers, weak and trembling, squeezed mine as if she needed to tether herself to this world for one last second, and the way she whispered something that didn’t make sense to me in that moment: “Don’t let him take what’s yours.”

I thought she meant my dignity, or my heart, or whatever pieces of myself I had not yet lost, but later I realized she meant something far more literal, something that would eventually lead me into a courtroom where everyone’s voice sounded like it had been dipped in ice.

After the funeral, the house transformed into a mausoleum of withheld truths; my stepfather walked through the halls like a warden, keys jingling in his pockets though nothing in the house had locks except his office, and every time I knocked on that door, he pretended not to hear me, as if acknowledging my existence was an inconvenience he could not afford.

Weeks passed, grief settled into my bones like wet cement, and yet he remained strangely buoyant, almost energized, as if mourning was a luxury he didn’t have time for—not when there were documents to sign, accounts to access, assets to “manage,” or whatever euphemism he used when he disappeared into his office for hours, emerging with the faint scent of printer ink and triumph clinging to his shirt.

It was only when he mistakenly left the office door slightly ajar one afternoon, letting a sliver of lamplight escape, that I caught a glimpse of him hunched over a stack of papers with my mother’s name at the top, his pen gliding with a familiarity that made something inside me freeze, because even from a distance, I could recognize the shape of a signature that should have been impossible for him to possess.

I asked him about it later, quietly, naively, believing that the truth could be extracted with politeness, but he simply laughed—a dry, humorless sound that felt like gravel scraping along the inside of my skull—and told me I was imagining things, that grief makes people paranoid, that young girls like me should not meddle in adult matters.

He spoke with such confidence, such paternal condescension, that for a moment I doubted myself, doubted what I’d seen, doubted whether the universe had given me a sign or a hallucination, but then he made a mistake, a small one, but fatal: he called me by the wrong nickname, the one my mother used only when she was deeply worried about me, the one he had no reason to know unless he had read something he shouldn’t have, unless he had been inside records that were never meant for his hands.

That was the moment I understood something was not just wrong—it was orchestrated, woven, intentional, and I realized I had to stop treating him like a family member and start treating him like what he truly was: a threat.

It took months of gathering the fragments, of talking to old lawyers, of tracing conversations, of deciphering the breadcrumbs my mother left behind; it took sleepless nights and trembling mornings, but eventually I found the document—the one that named me as the sole heir, the one he claimed did not exist, the one he buried so deep inside the filing cabinet that dust had begun claiming its corners, as if he assumed it would disintegrate before anyone found it.

And when I held it in my hands, my pulse became a frantic drum, because the truth was heavy, heavier than paper should be, heavier than the metal cabinet that hid it, heavier than every lie he had fed me, spoonful by spoonful, until I learned to swallow suspicion without choking.

I knew then that I had to expose him, not in whispers, not in private confrontations he could twist, but in a courtroom where every syllable was recorded, where lies were not just immoral but illegal, where he would finally have to face something he could not manipulate: evidence.

The day of the hearing felt unreal, like stepping onto a stage where the lights were too bright and the air too thin, where every step echoed as if the building itself was listening, waiting, anticipating the unraveling of a man who had spent years perfecting his disguise.

He sat across from me with the arrogance of someone who believes the world bends for him, wearing a suit that smelled like power, tapping his pen with the rhythm of a man who thinks he’s already won, and when his lawyer smiled at him, he smiled back with the certainty of a man who believes truth is subjective when you have money and confidence and the ability to lie without blinking.

But when the judge asked about the inheritance, when she requested the specific documentation he had sworn did not exist, I watched the first crack appear—not on his face, but in the way he inhaled, too sharply, too quickly, like someone choking on invisible smoke.

His hands trembled, faintly at first, then unmistakably, and his lawyer leaned toward him, whispering urgently, while he stared at the empty table in front of him as if he expected the documents to materialize through sheer force of will.

His mouth tightened, his jaw clenched, and for the first time since my mother’s death, he looked less like a man and more like a cornered animal, trapped in the snare he set for someone else, realizing too late that he had stepped into it himself.

The judge asked again—calmly, firmly, patiently—but he could not answer, not without exposing the truth, not without undoing the careful stitching of his entire story, and in that silence, thick and suffocating, I felt the world tilt.

He didn’t know that I…

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

There is a kind of evil that does not scream. It simply needs a smile at the right time and a pen placed in the wrong spot. I thought my mother’s funeral was the worst day of my life until I arrived home and found the locks had been changed. My stepfather told me softly that he ran the house now.

Then he made the biggest mistake of his life when he left behind one single document. My name is Zoe Sullivan and for 34 years I believe that grief was the heaviest thing a human being could carry. I was wrong. Betrayal is heavier because it does not just crush you, it unbalances you. It takes the solid ground of your memories and turns them into quicksand.

The day we buried my mother, Brier Glenn was drowning in a cold, unseasonal rain. It was the kind of weather that made the gray stones of the cemetery look like old teeth jutting out of the earth. I stood under a black umbrella that was not mine.

Shivering in a coat that felt too thin for the wind whipping off the Colorado foothills. My mother, Diane Sullivan, had been 49% of my world. The other 51% was currently occupied by a numbness so profound I could barely feel my toes. A stroke. That was what the doctors had said. Massive, sudden, a thief in the night that stole her voice, then her movement, and finally her breath. Standing next to me was Rex Holston, my stepfather.

He had his hand on my shoulder, a heavy, reassuring weight that I suppose looked comforting to the dozens of people gathered around the grave, to the neighbors, to mom’s friends from the library board, to the distant cousins who had flown in from Ohio. Rex was the picture of the grieving widowerower. He wore a charcoal suit that fit him perfectly.

His silver hair was combed back with dignified restraint, and his eyes were rimmed with just the right amount of red. She was the light of this house,” Rex said to Mrs. Gable, our next door neighbor, his voice trembling just enough to sell the performance. “I don’t know how Zoe and I will go on without her.” I looked at him. He was dabbing his eyes with a white handkerchief. It was a beautiful performance.

Truly, if I worked in casting instead of compliance, I would have hired him on the spot. But I work in compliance at Ridgeway Mutual Solutions. My entire career is built on noticing when the numbers do not add up, when a signature looks slightly off, or when a policy is being bent until it breaks.

And something about Rex was bending. It started at the funeral home an hour before we came here. We were in the private viewing room. The air smelled of liies and firmaldahhide, a cloying sweetness that sticks to the back of your throat. I was saying goodbye to mom, fixing the collar of her favorite blue silk blouse. Rex was pacing behind me. I need to check if the car is here, he had said.

I nodded, not looking away from mom’s face. I heard his footsteps recede, but they did not go to the door. They stopped near the small side table where the funeral director had placed mom’s personal effects. The bag contained the clothes she had worn to the hospital, her watch, and her purse.

I turned my head, just a fraction. It was a reflex. Rex was not checking the door. He was standing over the bag. His hand moved with the speed of a striking snake. He reached into the side pocket of mom’s leather tote, his fingers curling around a ring of keys. I knew those keys. There was a silver house keychain and a small brass one for the back shed.

He slipped them into his suit pocket in one fluid motion. Then he looked up and saw me watching him. For a second, the mask slipped. His eyes were hard, calculating, devoid of any sorrow. But just as quickly, the grief returned. He offered me a sad, watery smile. Just checking to make sure they didn’t lose anything. Zoe, your mother would have hated if things went missing.

He did not put the keys back. Now, standing at the grave, that memory played on a loop in my mind. Why would he take her keys? He had his own set. We all did. I had a key to the house I grew up in. The house mom had owned since before she ever met Rex. Zoe, Rex said, squeezing my shoulder again. The service was over.

People were drifting toward their cars. Listen, I know you are overwhelmed. You should take a few days. Don’t worry about the administrative side of things. Administrative side? I asked. My voice sounded rusty. The death certificates, the bank notifications, the bills, Rex said, guiding me toward the waiting limousine. I have already called my lawyer. We are handling the probate.

You are grieving. Sweetheart, you focus on healing. I will handle the paper, the accounts, even the mail. You don’t need to burden yourself with the boring stuff. He emphasized the word mail. It was subtle, but it was there. A slight pressure on the syllable. I can help, I said. I’m good with paperwork, Rex. It’s my job. Nonsense.

He dismissed me with a wave of his hand. You are the daughter. You mourn. I am the husband. I protect. We rode back to the house in silence. Or rather, I was silent. Rex spent the 20inut drive on his phone, typing furious text messages while shielding the screen from my view. When the reception ended and the last guest had eaten the last ham sandwich, I felt a desperate need to be alone in my old room. I wanted to smell mom’s perfume in the hallway.

I wanted to see the books on her nightstand. I wanted to feel closer to her. I think I will stay here tonight, I told Rex as I started gathering the trash from the living room. I don’t want to drive back to my apartment. Rex froze. He was standing by the fireplace, swirling a glass of scotch. Oh, Zoe, I don’t think that is a good idea. Why not? I need space, he said, his voice dropping to a whisper.

To be with her memory. Just me. You understand, don’t you? It’s been hard on our marriage lately. Her sickness. I need to say goodbye to my wife in private. It was a strange request. Mom had not been sick for long. It was a stroke, sudden. But he looked so pathetic, so broken that I relented. I was 34 years old.

I had my own apartment 20 minutes away. Fighting a grieving widowerower for territory on the day of the funeral felt petty. “Okay,” I said. I will come by tomorrow morning to pick up some of my things and some of hers. I want the photo albums. Tomorrow afternoon, he corrected quickly. Give me the morning.

I drove home, but I did not sleep. I stared at the ceiling, counting the cracks in the plaster. The image of the keys vanishing into his pocket would not leave me alone. The next day, I did not wait until the afternoon. I arrived at the house at 9 in the morning. The driveway was empty. Rex’s car was gone. I felt a surge of relief.

I could go in, grab the albums, maybe sit in mom’s chair for a moment without his performative sorrow hovering over me. I walked up the front steps, the wood still damp from yesterday’s rain. I pulled my keychain out of my purse, the brass key, worn smooth by 20 years of use, slid into the lock. It stopped halfway.

I frowned and jiggled it. Nothing. I pulled it out and tried again. It hit a hard metal barrier inside the cylinder. I took a step back and looked at the hardware. It was shiny, new, gold toned instead of the brushed nickel mom had installed last year. He had changed the locks in less than 24 hours since we put her in the ground.

Rex had changed the locks on my mother’s house. I felt a heat rise up my neck, a mixture of confusion and rage. I pounded on the door. Rex, Rex, I know you are in there. No answer. I walked around to the back. The kitchen door was also new. The windows were locked tight. I was locked out of my own childhood. I sat on the back porch swing, the one mom and I used to sit on to watch the fireflies. And I waited.

I waited for 2 hours. At 11:00, Rex’s sedan pulled into the driveway. He got out carrying a briefcase. When he saw me sitting on the front steps, he didn’t look surprised. He didn’t look apologetic. He looked annoyed. “I told you this afternoon, Zoe,” he said, walking past me to unlock the door. “You changed the locks,” I said, standing up.

My hands were shaking. “Why would you change the locks, Rex?” He pushed the door open and turned to face me. He blocked the entrance with his body. He was a tall man, broad-shouldered, and for the first time, he used that size to intimidate me. Security,” he said flatly. With the obituary out, “People know the house is vulnerable. I couldn’t be too careful.

You locked me out. I have a key. You had a key to the old lock.” He said, “This is my house now.” Zoe, I need to control who comes and goes. “My house.” He didn’t say our house. He didn’t say your mother’s house. “I want to come in,” I said, stepping forward. Actually, he said, holding up a hand. Wait here.

He stepped inside and closed the door in my face. I heard the deadbolt slide home. I stood there stunned for three long minutes. When the door opened again, Rex was holding a medium-sized cardboard box. He shoved it into my arms. It was not heavy. “What is this?” I asked. “Ite,” he said. “Personal effects.” I went through her things this morning.

I packed up what I thought you would want. Old photos, her high school yearbook, that ceramic cat she liked. You went through her things. I felt bile rise in my throat without me. I told you I am handling it, Rex said. His voice was calm, reasonable, terrifying. Zoe, we need to have a difficult conversation. I did not want to do this today, but you are pushing me.

He leaned against the door frame, crossing his arms. Your mother left a mess, Zoe. A financial disaster. I stared at him. Mom. Mom was the most organized person I knew. She had spreadsheets for her grocery budget. She hid it well. Rex sighed, shaking his head. gambling debts, bad investments, credit cards you didn’t know about.

The estate is underwater, deeply underwater, the house, the savings. It is all gone to creditors. I am trying to salvage what I can. But frankly, there is nothing left for you. I don’t believe you, I whispered. Believe what you want, he said, his eyes cold. The will is very simple.

It leaves everything to the surviving spouse to handle debts. That is me. This box, this is me being generous legally. Even those photos are assets I could sell to pay off her loans. He pointed a finger at the box in my arms. Take it. Go home. Grieve. Let me clean up this mess. Do not come back here unless I invite you. It is for your own good.

I don’t want you to see the foreclosure notices when they start pasting them on the door. He stepped back and closed the door. The sound of the lock clicking shut echoed like a gunshot in the quiet suburban street. I drove home in a daysaze. My apartment felt foreign, cold. I placed the cardboard box on my kitchen table and just stared at it. I did not cry. I was past crying.

I was in the cold analytical place that I usually reserved for auditing compliance reports at Ridgeway. Gambling debts. It was a lie. Mom thought buying a lottery ticket was a tax on people who were bad at math, bad investments. Mom kept her money in low yield municipal bonds because she was terrified of risk. I opened the box.

Rex had been thorough in his cruelty. It was filled with junk, a chipped mug, a scarf with a moth hole, a stack of photos from the 80s where mom’s eyes were closed. It was a collection of things that said, “This is what you are worth.” I started pulling things out, anger vibrating in my fingertips. I grabbed a stack of old paperback romance novels he had thrown in at the bottom. Mom used to read these on vacation.

As I fanned through the pages of a dogeared book titled The Duke’s Secret, a piece of paper fluttered out. It was not a bookmark. It was a piece of Ridgeway Mutual Stationer. I froze. Mom used to ask me for scrap paper from work for her grocery lists. I picked it up. The handwriting was unmistakable.

It was mom’s sharp, angular script, but it was shaky, as if she had written it in a hurry. Or perhaps in fear, it read Zoey. If you are reading this, Rex has likely told you that I left nothing. He has likely told you that I was in debt. Do not believe the smile. If he says I am empty-handed, go to the one place he cannot touch, ask about the blue folder.

I read it twice, then three times. My heart hammered against my ribs. Ask about the blue folder. She knew. She knew he would do this. She knew he would change the locks and rewrite history. I looked at the date scribbled in the corner of the note. It was dated 3 weeks ago, 2 days before the stroke.

I looked at the box of trash Rex had given me, thinking he was dismissing me, thinking he was erasing me, but he had made a mistake. In his arrogance, he had handed me the map. Rex Holston thought he had won. He thought he was the new king of the castle because he held the keys. But he didn’t know what I did for a living. He didn’t know that I hunt buried things for a paycheck.

I folded the note and slipped it into my pocket. The tears stopped. The shaking stopped. My mother was not broke and she was not stupid. I picked up my phone. I was not going to call Rex. I was not going to scream. I was going to find out what a blue folder was and I was going to use it to bury him. 3 days after the funeral, Rex invited me back to the house.

The text message was brief and framed as an olive branch. It said that we needed to clear the air and handle the boring paperwork so we could both move on with our lives. He used the word healing. I have learned that when a man like Rex talks about healing, he usually means amputation.

I parked my car on the street because the driveway was occupied by a silver Lexus I did not recognize. When I walked up to the front door, I did not bother reaching for my keys. I knew they would not work. I knocked and Rex opened the door wearing a casual beige sweater that made him look like a kindly grandfather from a catalog.

He ushered me into the living room. The air was stale, the windows closed tight. Sitting on the sofa was a man I had vaguely met once at a barbecue years ago, Arthur Vance. He was Rex’s friend, a lawyer who mostly handled real estate closings and minor traffic violations, not a state law, but there he was, sitting with a legal pad on his knees, smiling a smile that did not quite reach his eyes.

On the coffee table, right in the center, sat a stack of documents. They were crisp, white, and stapled with precision. Rex sat in mom’s favorite armchair. It made my stomach turn to see him there, claiming her space so effortlessly. Zoe, thanks for coming, Rex said, gesturing for me to sit on the love seat. Arthur and I have been going over the numbers. It is worse than I thought.

Honestly, the debts are piling up, but I have found a way to handle it, so it does not affect your credit or your future. Arthur Vance nodded. We want to keep this simple, Zoe. Probate court is a nightmare. It is public. It is expensive and it takes years. Rex is willing to absorb the liabilities, but to do that, we need to streamline the asset transfer. Rex leaned forward, pushing the stack of papers toward me.

It is just a standard formality, he said softly. It authorizes me to deal with the creditors directly. This way, they do not harass you. You just sign and I take on the headache. It is the last thing I can do for Diane to protect her daughter. My compliance training at Ridgeway Mutual kicked in immediately.

Rule number one, if someone rushes you to sign, they are hiding a clause. Rule number two, if they say it is for your benefit, it is usually for theirs. I picked up the stack. It was heavy. I’m going to read it. I said. Rex exchanged a quick, almost imperceptible glance with Arthur. Of course, Arthur said, though his tone suggested I was being unreasonable. Take your time.

But the banks close in 2 hours, and we were hoping to get this file today to stop the interest from acrewing. I ignored him and flipped past the first page, which was a generic cover letter. I scanned the legal jargon. It was dense, deliberately obtuse language about administrative authority and tax positioning.

But on page four, paragraph 3, I saw it. Disclaimer of interest. I read the sentence twice to be sure. The undersigned hereby disclaims, renounces, and surrenders any and all interest, right, or title to the estate of Diane Sullivan, whether by will, intestate succession, or otherwise. I looked up. The room felt suddenly very cold.

This is not a purely administrative document, Rex, I said, keeping my voice steady. This is a disclaimer of interest, Rex blinked, figning ignorance. It is well, that is just legal speak for letting me handle the accounts. Zoe, like I said, no, I said, I place the papers back on the table and flatten my hand over them.

This says I am voluntarily giving up my inheritance. If I sign this, I am saying I do not want anything. Not a scent, not a photo album, nothing. Arthur cleared his throat. It is a tax strategy. Zoe, if you disclaim the assets, they flow to the spouse who has a marital deduction. It saves the estate 40% in taxes.

Rex will of course take care of you privately. This just keeps the government out of it. Then put that in writing. I said what Rex asked. his brow furrowing. Write a separate contract stating that if I sign this disclaimer, you agree to pay me my share of the estate. Rex let out a long disappointed sigh. He took off his glasses and rubbed the bridge of his nose. Zoey, look at me.

I looked at him. I am your stepfather. I have been in your life for 10 years. Your mother just died and you are sitting here talking about contracts. You think I am trying to cheat you? me, the man who paid for your car insurance when you were 22, the man who held your mother’s hand while she took her last breath. It was a masterclass in deflection. He did not answer the question.

He attacked the character of the person asking it. I am not talking about the past. Rex, I am talking about this document. I am not signing a disclaimer. Rex stood up. The kindly grandfather act evaporated. He walked to the window and looked out at the street. I am trying to save you from her debt.

Zoe, if you accept the inheritance, you accept the liabilities, you will be bankrupt in 6 months. I am offering to take that bullet for you and you are treating me like a criminal. Show me the debts, I said. Show me the statements. If mom was in that much trouble, I want to see the red ink. Arthur stood up too, gathering his briefcase. I think we should give Zoe some time to cool down.

Rex, she is obviously very emotional right now. Grief makes us irrational. I am not irrational, I said, standing to meet them. And I am not signing. Rex turned to look at me. His face was a mask of pity. You are making a mistake, a very expensive mistake. I walked out of that house with my heart pounding in my ears. I did not sign, but I felt like I had lost something just by being there.

The retaliation began. And the next morning, it started with a text from my aunt Sarah, mom’s younger sister in Ohio. Zoe, I just got off the phone with Rex. I can’t believe you are fighting him over money before your mother is even cold in the ground.

He is trying to save the house and you are demanding payouts. I thought we raised you better. I stared at the screen, my thumbs hovering. Rex had spun the narrative overnight to the family. I was the greedy stepdaughter looking for a payday while he was the grieving husband trying to manage a financial crisis. He had poisoned the well. I tried to call Sarah but she sent me to voicemail.

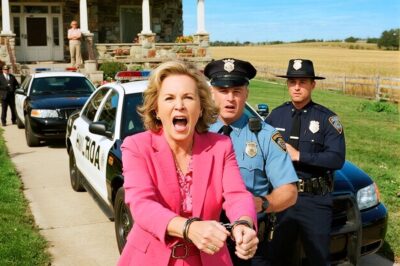

2 hours later while I was sitting at my desk at Ridgeway, the receptionist called me to the front. There was a man waiting for me. He was not a client. He was a process server. He handed me a thick envelope in front of my colleagues. Zoe Sullivan, you have been served.

I took the envelope back to my cubicle, my face burning. Inside was a notice from the probate court. Rex had filed a petition to be appointed as the personal representative of the estate. The petition stated that the deedent died in testate without a will and that as the surviving spouse, he had priority without a will. That was a lie. Mom had a will. She had shown it to me 5 years ago.

It was simple, splitting everything 50/50 between Rex and me. But if Rex had destroyed the physical copy in the house, and if I could not find another one, the state law would default to him. I grabbed my phone and walked out to the fire escape to call mom’s bank. I needed to stop him from accessing her accounts before a judge ruled on this.

I dialed the number for the local branch of Harborline Trust. Hello, my name is Zoe Sullivan, I said trying to keep the tremor out of my voice. My mother, Diane Sullivan, passed away recently. I am concerned about unauthorized access to her accounts. There was a pause followed by the clicking of a keyboard. I am sorry for your loss, Ms. Sullivan.

The banker said, however, I see a note on the file here. We have received documentation regarding the estate administration. Yes, but that is being contested. I said you need to freeze the funds. I cannot do that. The voice said detached and professional. Unless you are the courtappointed administrator or a joint account holder. I cannot discuss the details of the account with you.

But I am her daughter. That does not grant you legal authority. Ma’am, you will need to have your lawyer contact our legal department. I hung up, frustrated. Rex was moving at light speed. He knew the system. He knew that possession was 9/10 of the law, and he was grabbing everything he could hold. That weekend, I drove past the house.

I parked two blocks away and walked down the street, keeping my hood up. A white van was parked in the driveway. It had the logo of a local estate liquidator on the side. I watched from behind a neighbor’s hedge as two men carried out a large familiar object wrapped in moving blankets. The shape was unmistakable.

It was the grandfather clock that had stood in our hallway since I was a baby. It was an antique worth maybe $4,000. Then came the paintings, the landscapes mom had collected from local artists. He was not just selling things. He was liquidating the evidence of her life. He was turning assets into cash that could disappear into pockets where probate courts could not look.

If I tried to stop him now, he would just claim he was raising money to pay the debts he kept talking about. I wanted to run up the driveway and scream. I wanted to tackle the movers, but I knew that was exactly what Rex wanted. He wanted a scene. He wanted the neighbors to call the police so he could point at me and say, “See, she is unstable.

” I turned around and walked back to my car, feeling a physical ache in my chest. On Monday, the stress finally caught up with me at work. I work in compliance, analyzing risk reports for insurance policies. It requires absolute focus. You have to spot the anomaly in a sea of data. But that Monday, the numbers were swimming on the screen.

All I could see was Rex’s smug face and the empty space where the grandfather clock used to be. I missed a critical flag on a commercial liability renewal. It was a sloppy mistake, one that could have cost the company $50,000 if my manager, David, had not caught it during the final review. David called me into his office at 2:00 in the afternoon.

Zoe, this is not like you, he said, sliding the report across his desk. You have been staring at the same page for 3 hours. I am sorry, David, I said, rubbing my temples. My mother, it has been a lot. I know, he said, his voice softening. But I also got a call today. My head snapped up. A call from who your stepfather called HR. David said he was concerned.

He told them you are having a severe reaction to the grief. He mentioned you might be erratic. My blood ran cold. Rex had called my job. He was preempting me. He was planting the flag of insanity before I could even open my mouth. He had no right to do that. I said, my voice rising. He is lying. David held up a hand.

Zoe, you just missed a tier one compliance flag. That is a fireable offense. I do not think you are erratic, but I do think you are compromised. You are burned out. I am fine, I insisted, though I could feel tears pricking my eyes. You are not fine, David said firmly. I am putting you on mandatory administrative leave for 2 weeks.

Take the time, sort out the family business. Do not come back until you can focus on the numbers. I walked out of the office carrying a box of my personal things for the second time in a week. First my mother’s house, now my job. Rex was systematically dismantling the pillars of my life.

He was isolating me, stripping me of resources and discrediting my voice. I sat in my car in the parking lot of Ridgeway Mutual. The engine idling. I felt small. I felt defeated. I had no lawyer, no access to the accounts, and my own family thought I was a vulture. I reached into my purse to find a tissue and my fingers brushed against the folded piece of paper I had found in the romance novel.

If Rex says I am white-handed at the one place he cannot touch, ask about the blue folder. I pulled the note out and smoothed it against the steering wheel. Rex was winning the war on the surface. He was winning the battle of public opinion, the battle of speed, and the battle of brute force, but he was fighting a conventional war.

He thought this was about bullying a stepdaughter into submission. He did not know about the blue folder. I wiped my face. I stopped crying. Mom had anticipated this. She knew he would cut off the money. She knew he would lie to the family. She knew he would try to break me. That was why she did not leave the will in the desk drawer. That was why she did not trust the house safe.

I had been trying to fight Rex by yelling at the walls he had built. That was a waste of energy. I needed to stop reacting to his moves and start making my own. I put the car in gear. I was not going home to sulk. I was going to find out what my mother had hidden. If Rex wanted to play games with paper, I would show him that paper cuts could bleed a man dry.

I typed the name of mom’s old estate planning firm into my GPS. It was time to stop being the victim and start being the auditor. The address for Calder and Rook estate law was buried in a stack of old holiday cards I found in the bottom of a kitchen drawer at my own apartment.

My mother was the type of person who saved return addresses, tearing the corners off envelopes just in case she needed to send a thank you note 3 years later. I found a Christmas card from 5 years ago sent by a woman named Margaret, who I vaguely remembered was a parallegal mom had befriended at her book club. The return address was a suite in a brick building downtown, not far from the courthouse.

I took a personal day for my administrative leave, which felt like a bitter irony, and drove downtown. Brier Glenn is not a large city, but it has a district where the old money lives, sleeping quietly in limestone buildings with brass plaques. Calder and Rook was one of those places. It smelled of lemon polish and billable hours.

When I walked into the reception area, the silence was heavy. The carpet was thick enough to swallow the sound of my boots. Behind the high mahogany desk sat a young receptionist who looked like she was barely out of law school. She was typing furiously, her headset blinking. I waited for her to finish. When she looked up, her professional smile was practiced and tight.

“Can I help you?” she asked. My name is Zoe Sullivan, I said, resting my hands on the cool wood of the desk. I am looking for the attorney who handled the estate planning for Diane Sullivan. She was a client here. The receptionist’s fingers stopped moving. The smile faltered just for a fraction of a second before she recomposed herself. She typed my mother’s name into her system.

I saw her eyes dart to a note on the screen and then she looked at me with a different expression. It was guardedly polite the way one looks at a liability walking through the door. Ms. Sullivan, she said, her voice dropping a decibel. Mr. Calder is the partner who oversaw that file. However, I show here that the representation was transferred. Transferred? I asked. To whom? To Mr.

Arthur Vance? She said, we received a formal request to transfer all physical files regarding the Sullivan estate 3 days ago. Three days ago, the day after the funeral, Rex had been faster than I could have imagined. He had not just changed the locks on the house, he had scrubbed the legal record. “Did my mother authorized that transfer?” I asked, knowing the answer.

The request came from the personal representative of the estate. She said, “Mr. Rex Holston, since he provided documentation of his status, we were legally obligated to release the files. I felt the door slamming in my face again. It was the same wall I had hid at the bank. Rex was using his assumed authority to erase the history of what my mother actually owned.

“Thank you,” I said, turning to leave. There was no point in arguing with the receptionist. She was just the gatekeeper. I was halfway to the heavy glass doors when I heard a voice behind me. Ms. Sullivan. I turned. A woman had emerged from a hallway behind the reception desk.

She was older, perhaps in her 60s, wearing a cardigan and reading glasses on a chain. It was Margaret, the parillegal from the Christmas card. She looked different than I remembered, more tired, her shoulders hunched slightly under the weight of too many files. Margaret, I asked. She didn’t smile. She walked past the receptionist, holding a stack of Manila envelopes as a prop. Walk with me, she said, not stopping.

I am going to the archives in the basement. I followed her. We bypassed the elevators and took the stairs. The heavy fire door clicking shut behind us, cutting off the polished silence of the lobby. The stairwell was concrete and cold. Margaret’s heels clicked sharply on the steps.

She did not speak until we reached the bottom landing, and she swiped a key card to open a room that smelled of dust and old paper. Rows of metal shelving stretched out under buzzing fluorescent lights. It was a graveyard of disputes and resolutions. Thousands of boxes filled with the secrets of Brier Glenn’s dead. Margaret walked to the end of an aisle and stopped. She turned to face me.

Her expression severe, but her eyes kind. I am sorry about your mother. Zoe, she said Diane was a good woman. She made the best lemon tart I have ever tasted. She was terrified. I said I found a note. She told me to ask about a blue folder. Margaret let out a short sharp breath. She looked around the empty room, paranoia radiating off her. The blue folder, she whispered.

We used to joke about it. Your mother called it her in case of Rex file. So it existed. I said it did. Margaret said it sat in the safe in Mr. Calder’s office for 4 years. It was not part of the main client file. It was held in custody. Where is it now? Gone, Margaret said. Rex Holston came in here on Tuesday morning.

He had Arthur Vance with him. They had a court order regarding emergency access to estate documents. Mr. Calder is a good lawyer, but he is risk averse. He handed it over. The blue folder, the main will, the trust documents, all of it. My heart sank. So he destroyed it. I said likely. Margaret nodded.

If Rex is as smart as Diane feared he was, that folder is ashes in a fireplace by now. I leaned against the metal shelving, the defeat washing over me. Then there is nothing. He won. Margaret hesitated. She looked at the door, then reached into the pocket of her cardigan. Rex took the files, she said softly. But he did not understand how this office works. When we prepare a complex trust, we draft emails. We scan exhibits.

We have digital backups that do not sit in the client folder. I cannot give you the file, Zoe. That would be a breach of privilege, and I would lose my pension. She pulled out a folded piece of paper, but I was cleaning out my own email outbox yesterday, deleting old correspondence. I found this. It is a print out of an email I sent to your mother two years ago when we were funding the trust.

It is not the trust itself. It is just an attachment confirmation. I took the paper. It was a single sheet, a print out of an email thread. The subject line read, “Trust certification, exhibit C review.” I scanned the text. It was dry, boring legal talk. Dear Diane, please find attached the revised schedule A for your review before we finalize the funding of the Mercer Legacy Trust.

The Mercer Legacy Trust, I repeated, not the Sullivan Estate. Your mother’s maiden name was Mercer, Margaret said. She established a revocable living trust 5 years ago. Rex was never a trustee. He was never a beneficiary of that specific trust. I looked at the paper again. There was a handwritten note in the margin of the email printout.

In Margaret’s handwriting, client instructed original schedule A to be placed in safe deposit box 404. Schedule A, I said, looking up in my line of work. Schedule A is the asset list. It is the inventory. Exactly. Margaret said, “A trust is just an empty bucket until you put things in it. Schedule A is the list of things in the bucket.

If the house, the accounts, and the investments were retitled into the name of the Mercer Legacy Trust, then they are not part of the probate estate. Rex has no authority over them.” “But Rex is acting like he owns everything.” I said, “Because he has the keys,” Margaret said.

“And because he thinks he destroyed the only map that tells you where the treasure is buried. He thinks if he hides the trust instrument, the trust ceases to exist.” She stepped closer, lowering her voice to a whisper that barely rose above the hum of the ventilation system. “Diane was afraid of him.” “Zoe.” She came in here once with a bruise on her arm. She said, “Was from a cabinet door, but she was shaking.

” She told me, “If I die, do not let him sign for me. He practices my signature.” The chill that went down my spine had nothing to do with the basement temperature. Practices her signature. Margaret nodded. “You did not hear that from me. But you need to move fast.

If he finds out about the safe deposit box, or if he finds a way to forge access to it, the schedule A will disappear, too. And without that list, you cannot prove what belongs to the trust. I folded the paper and put it in my bag. Thank you, Margaret. Get a lawyer, she said, turning back to the shelves. And not a nice one.

Do not get a family law attorney who wants to mediate. Get a litigator. Get someone who enjoys blood sport. I left the building with the single sheet of paper pressed against my side like a weapon. The sun was setting, casting long orange shadows across the pavement. I sat in my car and looked at the email print out. Mercer Legacy Trust. My mother had not just hidden money.

She had built a fortress. And Rex was currently squatting in the courtyard. Pretending he owned the castle. I needed a general for this war. Margaret was right. I did not need a lawyer who would write polite letters. I needed someone who would kick the door down. I pulled out my phone and searched for litigation attorneys in Denver and the surrounding areas.

I scrolled past the ones with smiling faces and slogans about protecting your family. I looked for the ones with sharp eyes and track records of aggressive winds. One name kept coming up in the forums I frequented for compliance officers. Catherine Shaw. She was a partner at a boutique firm called Shaw Miller. The reviews were polarized. Half of them were five stars.

praising her tenacity. The other half were one star written by people who had lost against her, calling her ruthless, cold, and a shark. She was perfect. I called her office. It was 6:00 in the evening, but a human being answered the phone. I told the assistant I had a trust fraud case involving a stolen inheritance and a potential forgery.

I was given an appointment for 8:00 that same night. Catherine Shaw’s office was not in the old money district. It was in a modern steel and glass tower that looked like a jagged knife slicing into the skyline. When I arrived, the reception was empty, but a light burned in a corner office. Catherine came out to meet me herself.

She was a woman of indeterminate age, perhaps 40, with hair cut in a sharp bob as severe as a blade. She wore a black suit that looked like armor. “Zoe Sullivan,” she said. She did not ask. She stated it. Come in. Her office was chaotic but organized. Stacks of files covering every surface, but clearly categorized.

She cleared a chair for me and sat behind her desk, steepling her fingers. Tell me the story, she said. And do not leave out the ugly parts. I told her everything. the funeral, the keys, the changed locks, the disclaimer of interest document Arthur Vance had tried to make me sign, the liquidation of the furniture, and finally the conversation with Margaret and the email about the Mercer Legacy Trust. I handed her the print out.

Catherine put on a pair of reading glasses and studied the document for a long time. She did not speak. She tapped a pen against the desk, a rhythmic, predatory sound. Arthur Vance is an idiot, she said finally, tossing the paper onto the desk. But Rex Holston is not. What do you mean? I asked.

Rex knows that a disclaimer of interest is the quickest way to bypass a trust he cannot legally break, she explained. If you disclaim, the assets flow as if you predesceased your mother. Depending on the trust terms, that might make him the default beneficiary. He tried to trick you into cutting your own throat. She stood up and walked to a whiteboard covered in diagrams of another case.

She wiped a small corner clean and wrote, “Merc Legacy Trust in red marker. Here is the problem, Zoe. We know the trust exists. We know schedule A exists, but we do not have them. The courts operate on evidence, not ghost stories. If we walk into a judge’s chambers tomorrow and say Rex stole it,” the judge will ask for proof.

Rex will say there never was a trust or that Diane revoked it before she died. She turned to look at me, her eyes intense. But you said something interesting. You said he is selling the furniture. He is rushing the probate application. He is desperate to get the bank access. Yes, I said. He said she was in debt. Catherine laughed. It was a dry, humorless sound. He is lying.

If she was in debt, he would be walking away. not digging in. Men like Rex do not fight for scraps. He is fighting because there is a feast and he is terrified you will find the menu. She walked back to her desk and leaned over. Looking me dead in the eye. He is not hiding the money.

Zoe, money is hard to hide in the modern world. Digital footprints are everywhere. He is hiding the path to the money. He is hiding the legal vehicle, the trust that dictates where the money goes. He is trying to create a situation where the only visible path is the one that leads to him. What do we do? I asked. We stop looking for the money. Catherine said.

We look for the irregularity. We look for the mistake. He is moving too fast. When people move this fast, they trip. She picked up the email print out again. This note says, “Schedule A is in a safe deposit box. That is our entry point. But we cannot just walk in. The bank is stonewalling you. They said only the authorized representative can access it.

I said, “Correct,” Catherine said. And right now, thanks to his quick filing, that is Rex, but there is a back door. If we can prove that the safe deposit box is titled to the trust and not to Diane Sullivan individually, then Rex’s probate authority means nothing. His powers as a personal representative stop at the border of the trust.

She sat down and pulled a retainer agreement from a drawer. I cost $400 an hour, she said. And I require a $5,000 retainer upfront. I did not blink. I had $5,000 in my savings account. It was my emergency fund. Money I had saved for a new car or a medical crisis. This was an emergency. I will write you a check, I said. Catherine smiled.

It was the first time she had smiled, and it was terrifying. It was the smile of a wolf that had just caught a scent. “Good,” she said. “Go home and sleep, Zoe. Tomorrow, we are going to the bank and we are going to ruin Rex Holston’s day.” I signed the check. My hand did not shake. For the first time since mom died, I did not feel like a grieving daughter. I felt like a plaintiff.

As I drove home, the city lights blurring past. I replayed Catherine’s words. He is hiding the path. Rex had tried to erase the map. He had tried to burn the bridges, but he had forgotten one thing. I was a compliance specialist. I spent my life looking at broken paths and figuring out where they were supposed to go. Rex had left a paper trail, no matter how faint.

And with Catherine Shaw holding the flashlight, I was going to follow it all the way to the truth. The blue folder might have been gone, but the ghost of it was about to haunt him. The war had just moved from the living room to the courtroom, and I was bringing ammunition. Harborline Trust and Bank was designed to make you feel small. The ceilings were vated like a cathedral.

The floors were polished marble that echoed every footstep, and the tellers sat behind thick glass partitions that might as well have been castle battlements. When I had called them over the phone, I was just a grieving daughter begging for information. Today I was walking in with Catherine Shaw. The difference was palpable. Catherine did not walk. She cut through the space.

She wore a tailored crimson blazer that stood out against the gray and beige of the bank interior like a warning flare. I trailed a half step behind her, clutching my purse, my heart hammering a nervous rhythm against my ribs. We approached the main desk. The woman behind the counter was the same one I had spoken to on the phone.

a stern woman with reading glasses perched on the end of her nose. She looked up, ready to dispense the same rehearsed rejection she had given me days ago. “Can I help you?” she asked, her tone flat. Catherine placed her leather briefcase on the counter. It made a heavy solid thud. We are here to see the branch manager regarding the Mercer Legacy Trust, Catherine said.

Her voice was not loud, but it carried a frequency that commanded attention. I am Catherine Shaw, retained counsel for Zoe Sullivan, the beneficiary. The teller side, removing her glasses, as I explained to Ms. Sullivan previously, without the personal representative present. Catherine cut her off. She did not raise her voice.

She simply slid a single piece of paper across the marble. It was the copy of the email Margaret had given me, the one referencing exhibit C, and the funding of the trust. That is a confirmation of trust funding held at this institution. Catherine said, “Under banking regulations, you are required to acknowledge the existence of a fiduciary account to a named beneficiary.

If you refuse, I will be filing a complaint with the state banking commission before lunch, and I will name you personally in the obstruction suit.” The teller looked at the paper, then she looked at Catherine, then she looked at me. The color drained from her face.

The name Mercer Legacy Trust seemed to trigger something specific in her training, or perhaps in a memo she had recently read. “Please wait one moment,” she said, her voice suddenly trembling. She picked up her phone and whispered urgently. I watched her eyes dart toward the back offices. 2 minutes later, a heavy oak door opened and a man in a navy suit hurried out.

He was balding with a sheen of sweat on his forehead despite the aggressive air conditioning. Ms. Shaw, Ms. Sullivan, he asked, extending a hand that felt damp. I am Robert Sterling, the branch manager. Please come with me. He did not take us to a cubicle. He led us past the rows of tellers, through a secure door, and into a private conference room in the back.

The walls were lined with dark wood, and the center of the room was dominated by a mahogany table that could seat tw um Mr. Sterling closed the door and locked it. The sound of the latch clicking shut was heavy and final. The ambient noise of the bank, the counting of cash. The murmuring of customers vanished instantly. It was a vacuum of silence.

Please sit. Mister Sterling said. He sat opposite us, clasping his hands together on the table. He looked nervous. Bankers usually look bored or superior. They only look nervous when they know there is a compliance issue that could cost them their license. We are aware of the situation with Mrs. Sullivan’s passing. Mr. Sterling began. My condolences.

Save it. Catherine said. She opened her briefcase and pulled out a yellow legal pad. Let us talk about the Mercer Legacy Trust. Does it exist, Mr. Sterling hesitated, then nodded. It does. And is my client Zoe Sullivan, the named beneficiary? Yes, he said quietly. She is the sole primary beneficiary upon the death of the grtor, Diane Sullivan.

I felt the air leave my lungs in a rush. It was real. For days, Rex had made me feel like I was crazy, like I was imagining a fortune that didn’t exist. But here it was, confirmed by a man in a suit. I was not crazy. I was right. Then why? Catherine asked, leaning forward.

Was my client told she had no access? Why is Rex Holston parading around town acting as if this trust is part of the general probate estate? Mr. Sterling loosened his tie. It is complicated. Make it simple. Catherine said, “The account is currently in a state of soft freeze.” Mr. Sterling said. Soft freeze? I asked. What does that mean? It means the assets are there, but we have flagged them for internal review, he explained.

We had an attempted access event that triggered our fraud prevention protocols. What kind of access event? Catherine asked, her pen hovering over the paper. Mister Sterling looked at me, his expression pained. 3 days after your mother passed, Mr. Hol attempted to transfer funds from the trust’s checking account into a new external account. He presented a durable power of attorney document.

Catherine let out a short, sharp laugh. A power of attorney expires at the moment of death. Exactly. Mr. Sterling said, “We explained this to him. He became quite agitated. He insisted that the power of attorney was valid because he was the husband. We denied the transfer. However, because he is also petitioning for personal representative status in probate court, our legal department advised us to freeze the trust assets until the court determines who the rightful trustee is.

Wait, I said, my mind racing. Who is the trustee? If mom died, who runs the trust? Sterling opened a folder he had brought with him. According to the trust certification on file upon the death of Diane Sullivan, the successor trustee was to be a corporate fiduciary or if they declined, Mr. Holston could serve as a temporary trustee. But there were conditions.

What conditions? Catherine demanded. Mr. Sterling slid a piece of paper across the table. It was a photocopy of a clause from the trust. In the event Rex Holston assumes the role of temporary trustee, he must file a full inventory and affidavit of assets with the institution within 30 days of the grtor’s death.

Furthermore, he is prohibited from liquidating, selling, or transferring any real property or investment assets until said affidavit is approved by the beneficiary. I read the words. Mom had handcuffed him. She had known he would try to grab the money, so she had built a wall. He could only touch the wheel if he told me exactly how much gas was in the tank. He hasn’t filed the affidavit. Have you? Catherine asked.

No, Mister Sterling said. He has not, which is why we have not given him control of the funds, but he has been pressuring us. He calls every day. He is trying to bypass the trust, Catherine said, making a note. He wants to drag the assets into probate where he controls the narrative. She looked up at the manager.

Now, let us talk about the safe deposit box. Mr. Sterling stiffened. Box 404. Margaret told us the schedule A the list of assets is in that box. I said, I need to see it, Mister. Sterling shook his head. I cannot let you open it. Not yet. Until the trustee issue is resolved. The box is sealed. Catherine narrowed her eyes.

I want the access log. The manager blinked. I beg your pardon. I want the access log, Catherine repeated, her voice turning to steal. I want to know who has entered that box in the last 2 weeks. That is not confidential financial data. That is physical security data. My client is the beneficiary. She has a right to know if the physical integrity of the trust’s assets has been compromised.

Mister Sterling hesitated for a long moment. Then he stood up. I can provide the log history. Wait here. He left the room. The silence rushed back in. He is terrified. Catherine whispered to me. Why? I asked. Because they let Rex do something they shouldn’t have. She said, “Banks don’t freeze accounts unless they made a mistake and are trying to cover it up while they fix it.” “Mr.

” Sterling returned with a single sheet of paper. “He placed it in front of us.” I looked at the list of dates and times. My finger traced down the column. February 12th, Diane Sullivan. February 14th, Diane Sullivan. March 3rd, Rex Holston. March 3rd, that was two days after mom died. That was the morning he changed the locks. He was here, I whispered.

He came here before the funeral. And look at the time, Catherine said, pointing 9:15 in the morning. The bank opens at 9. He was waiting at the door. Mr. Sterling, Catherine said, looking up. How did Rex Holston get into this box on March 3rd? If the power of attorney was invalid for the transfer, it was invalid for the box.

Mister Sterling’s face turned a shade of gray I had never seen on a living person. That is the matter in question, he said. The employee who granted him access is no longer with the branch. She was a junior associate. Mr. Holston was very persuasive. He told her he needed to retrieve a burial deed. She bypassed the death certificate check. So he stole the contents.

I said, “My voice rising.” He went in, took the schedule A, took the trust document, and left. That is why he is so confident. He thinks he erased the evidence. Catherine placed a hand on my arm to silence me. She was looking at Sterling with a predator’s focus. Mr. Sterling, if you allowed an unauthorized person to access a trust safety deposit box and remove assets, this bank is liable for the entire value of that trust. We are talking about a negligence lawsuit that will make the morning news. Mr.

Sterling wiped his forehead with a handkerchief. We are aware of the exposure. Ms. Shaw, that is why we issued the notice of irregularity. He pulled one last document from his folder. It was stamped with red ink. internal use only. Notice of irregularity. He pushed it toward us, keeping his fingers on the corner as if he were afraid to let it go.

“We normally do not share this,” he said, his voice dropping to a whisper. “But if you are going to court, you should know.” When Mr. Hol accessed the box on March 3rd, he was required to sign the entry card. and Catherine asked and we compared his signature on that card with the signature on the power of attorney document he had on file.

He paused looking at the door to make sure we were still alone. They match perfectly. Mister Sterling said too perfectly. What do you mean? I asked. Human beings never sign their name exactly the same way twice. He said there are always microscopic variations in pressure, angle, loop size, but the signature on the entry card and the signature on the power of attorney document are identical, digitally identical.

Catherine’s eyes went wide. He used a stamp or a machine, Sterling said, or he traced it. But there is something else. The power of attorney document itself, the one he used to try and move the money, it is dated February 28th. That was the day mom had the stroke. I said she was in a coma. She couldn’t sign anything. Exactly.

Sterling said, “We have flagged the document as potentially fraudulent. That is why the account is frozen. We suspect Mr. Holston does not just have unauthorized access. We suspect he has a forged authorization.” I stared at the paper. A notice of irregularity. It was a dry banking term for a crime. Rex hadn’t just bullied me.

He hadn’t just played mind games. He had committed a felony. Catherine snatched the paper from under Sterling’s hand. I am taking this, she said. Mr. Sterling didn’t argue. I think that would be best. If you can get a court order, Ms. Shaw, we will open the box for you.

We want this resolved just as much as you do. We stood up. I felt unsteady on my feet, but it wasn’t from grief anymore. It was the adrenaline of discovery. Thank you, Mr. Sterling. Catherine said, “You have been very helpful.” We walked out of the private room, back through the silent bank, past the staring teller.

The air outside smelled of exhaust and rain, but to me it smelled like oxygen. Catherine stopped on the sidewalk and held up the notice of irregularity. “We have him,” she said. He forged it, I said. The reality sinking in. He forged her signature while she was dying and he got greedy. Catherine said he came to the bank too soon. He left a footprint. She put the document in her briefcase and snapped it shut.

I am going to draft a petition for an emergency hearing. She said, “We are going to ask the judge to compel the production of that notary journal. If he forged a power of attorney, he needed a notary. and if he has a notary in his pocket, we are going to burn them both. I looked back at the bank. It no longer looked like a fortress that was keeping me out.

It looked like a vault that was keeping Rex’s secret safe until I was ready to come for them. I felt a strange sensation in my chest. The heavy crushing weight of the last week was lifting. My mother was not just a victim. Even in death, she had left tripwires. She had forced him to forge papers because she hadn’t given him the real ones. I am ready. I told Catherine.

Good, she said, checking her watch. Because now we have to deal with the fact that while we were in there, Rex probably filed three more motions against you. Let us go to war. Zoe, I got into my car. I didn’t turn on the radio. I just drove. My mind replaying the image of the access log. March 3rd.

The day he told me he was protecting the estate. He was not protecting it. He was looting it. And now I had the receipt. Peace is a luxury I could not afford. After the victory at the bank, I allowed myself exactly 1 hour of relief before the sky fell in again. I was sitting on my living room floor, surrounded by photocopies of the notice of irregularity. When the doorbell rang, it was not a polite ring.

It was the sharp authoritative double buzz that usually means trouble. I looked through the peepphole. It was a sheriff’s deputy. My stomach dropped. I opened the door, trying to look like a woman who was not plotting the downfall of her stepfather. But the deputy did not look interested in my demeanor. He handed me a folded stack of papers.

Zoe Sullivan, you have been served. This is a temporary restraining order filed by Rex Holston. You are required to stay 500 ft away from him and the residence at 42 Oak Creek Drive. I took the papers, my hands trembling with a rage so hot it felt cold. A restraining order. He was flipping the board. I watched the deputy walk away. Then I slammed the door and tore open the packet.

The affidavit attached to the order was a work of fiction so complete it belonged on a bookshelf. In it, Rex claimed that I had come to the house screaming and banging on the doors, that I had threatened physical violence during the funeral, and that I was harassing a grieving widowerower for money.

He had taken my confusion and my grief and twisted them into a weapon, but he was not done. 20 minutes later, my phone pinged with a notification from my work email. I was on administrative leave, but I still had access to the server. The subject line was forward concern regarding Zoe Sullivan. It had been forwarded to me by David, my boss, with a simple note.

Zoe, do not reply to this. Call me. I opened the email. It was from Rex. He had sent it to the general HR inbox at Ridgeway Mutual Solutions, to whom it may concern. I am writing to you with a heavy heart regarding my stepdaughter, Zoe Sullivan. As you know, her mother recently passed. I feel it is my duty to inform you that Zoe is suffering from a severe mental break.

She has been making wild accusations and I fear maybe using her position to forge financial documents to cope with her loss. I am worried she is a danger to herself and potentially to your company’s integrity. Please get her help. Sincerely, Rex Holston. I dropped the phone. It clattered against the hardwood floor. He was not just trying to steal the inheritance.

He was trying to kill my future. He knew that in compliance, reputation is everything. If I was flagged as unstable or a forger, my career was over. He was projecting his own crimes onto me, accusing me of forgery because he had forged the power of attorney. It was a tactic so dirty, so thorough that I almost admired the brutality of it.

I did not have time to call David. I did not have time to scream because the doorbell rang again. This time when I looked through the peepphole, it was not just one deputy. It was two officers in uniform. And standing behind them, looking like a broken man holding a tissue to his nose, was Rex. I opened the door. Miz Sullivan, the taller officer asked. We have received a complaint of theft.

Theft? I repeated, staring past him at Rex. Rex would not meet my eyes. He looked at the ground, shaking his head. I am so sorry officers. I did not want to involve the police. I just want Diane’s things back. What things? I demanded. Stepping onto the porch. Mister Holston claims you entered the property on March 3rd and removed several items of high value.

The officer said, “A diamond tennis bracelet, a vintage Rolex, and a folder of financial documents.” I laughed. It was a sharp, hysterical sound. He changed the locks. I couldn’t get in. “You have a key, Zoey,” Rex said softly. His voice was thick with fake tears. “You used the old key to scratch the door and then you climbed through the back window.

I found the latch broken. You are lying.” I said, “You are a liar, Rex.” “Ma’am, calm down,” the officer said, putting a hand on his belt. “We need to ask you if you have these items in your possession.” “I do not. I said, “You can search the apartment. I have nothing.” Rex looked up then. For the first time, he looked directly at me.

His eyes did not look at my face. They drifted down to the large leather tote bag I had dropped by the door when I came in from the bank. He stared at that bag with a hunger that gave him away. He did not care about a diamond bracelet. He did not care about a Rolex. He was looking for the papers.

He was looking for the evidence he knew I was hunting. He thought I had found the blue folder or the schedule A and he had brought the police here to legally search my bag and take them back. Officer, Rex said, pointing a trembling finger. That bag? She always carries her things in that bag. If she took the documents, they would be in there. The officer looked at me.

Ma’am, do you consent to a search of that bag? I looked at Rex. I saw the panic behind his performance. He was desperate. He had taken a massive risk bringing the police here, hoping to catch me with the documents. “Go ahead,” I said. I picked up the bag and dumped it upside down on the porch.

My wallet fell out, my keys, a lipstick, a pack of gum, and the single folded photocopy of the email from Margaret, which looked like nothing more than a scrap of trash. There were no diamonds. There was no blue folder. Rex’s face fell. For a split second, the grieving widowerower vanished, replaced by a man who realized he had just swung at the devil and missed. “Is that everything?” the officer asked, “Looking at the pile.” “That is everything,” I said.

Rex stared at the pile. He looked furious, but he recovered quickly. He rubbed his eyes. “Maybe she hid them inside,” he muttered. “Or maybe she sold them already.” “Mr. Hol,” the officer said, his tone shifting slightly. You said you saw her take them today, I assumed. Rex stammered. I mean, they are missing. She is the only one with a motive.

The officer turned back to me. Ms. Sullivan, we are going to write a report, but without evidence of possession or forced entry, we cannot detain you. However, given the restraining order, I suggest you stay away from your stepfather. I am not the one who came to her house. Officer, I said coldly. The police ushered Rex away.

He walked back to his car, his shoulders hunched, but before he got in, he turned and looked at me one last time. It was a look of pure hatred. He knew I had something, but he couldn’t prove what it was. As soon as their cruiser turned the corner, I called Catherine. He called the cops on me. I said, my voice shaking, he accused me of theft.

He tried to get them to seize my bag. Catherine listened to the whole story. She did not sound worried. She sounded vindicated. He is flailing. Zoe, she said, a man who feels safe does not file a restraining order and call the police on the same day. He is trying to build a wall of noise to drown out the signal. He emailed my job. I said he told them I was forging documents.

Good, Catherine said. Good. How is that good? Because it proves malice. She said it proves a pattern of harassment, but more importantly, Zoe, did you see how he looked at your bag? Yes. I said he couldn’t take his eyes off it. He thinks you have the schedule A, she said. That means he hasn’t found it.

That means the safe deposit box is still the key. She paused, the sound of her typing in the background. I want you to do one thing, Zoe. Go to the police station tomorrow morning. Request the body cam footage from the officers who came to your door. Why? Because I want a jury to see his eyes, Catherine said.

I want them to see a grieving husband who isn’t looking at his stepdaughter but is scanning her property for a piece of paper. It shows intent. It shows he is on a hunt. I hung up and sat on my porch steps. The adrenaline was fading, leaving me exhausted. I felt dirty. I felt like he had dragged me through the mud.

And no matter how much I showered, I would still look like a suspect to my neighbors, to my boss, to the world. That is how men like Rex win. They do not need to be right. They just need to make you look wrong enough that people stop listening. I went inside and made a cup of tea I didn’t drink. I stared at the wall. The sun went down and the apartment filled with shadows. At 10:00, my phone buzzed.

I thought it was David or maybe another threat from Rex. I picked it up. It was a text message from an unknown number. The area code was from Florida. I opened it. There was no greeting, no name, just three sentences that stopped my heart. Check the marriage license. Rex was married to a woman named Jenna in Tampa in 1998.

I don’t think he ever signed the divorce papers. I stared at the screen. The light from the phone was the only thing in the dark room. I don’t think he ever signed the divorce papers. If Rex was not legally divorced from his first wife, then his marriage to my mother was void. It was bigamy.

And if the marriage was void, he was not the surviving spouse. He was not the next of kqin. He was a legal stranger. He had no right to be the personal representative. He had no right to the house. He had no right to check a single box on a single form. He wouldn’t just lose the money. He would lose his standing to even step foot in the courtroom.

I typed back, “Who is this?” The dots appeared, then disappeared, then appeared again. Someone who wants to see him burn as much as you do. I took a screenshot of the message, then another. I sat back against the couch cushions and let out a breath I’d been holding since the funeral. Rex had spent the day attacking my character. He had called me a thief, a liar, a forger, and a mental case.

He had tried to bury me under a mountain of shame, but he had forgotten to check his own foundation. I forwarded the screenshot to Catherine with a note. We need a private investigator in Tampa. The war had shifted. It was no longer just about who got the money. It was about who Rex Hol actually was.

And if this text was true, the man trying to kick me out of my mother’s house was about to find out that he didn’t even have a ticket to the show. The text message about Rex’s potential bigamy was a grenade. But Catherine Shaw insisted we do not pull the pin just yet. She wanted more ammunition.

She wanted to bury him under so much evidence that when we finally detonated the marriage license, he would already be buried up to his neck in fraud charges. So while the private investigator started digging in Florida, Catherine hired Marcus. Marcus was a forensic accountant. He did not look like a detective.

He looked like a high school algebra teacher who had given up on joy. He wore short-sleeved dress shirts and spoke in a monotone that made the most exciting theft sound like a weather report. We met in Catherine’s conference room 2 days after the incident with the police. The table was covered in bank statements, credit reports, and the inventory list Rex had partially submitted to the probate court. “This is sloppy,” Marcus said.

He did not look up from the spreadsheet on his laptop. “How sloppy?” Catherine asked. “Amateur hour,” Marcus said. He turned the laptop around so we could see. Rex claimed your mother left significant debts, Marcus explained. He listed four promisory notes totaling $120,000. He claims these are personal loans she took out over the last year to cover gambling losses. I shook my head.

Mom never gambled. She thought bingo was a waste of time. The notes look official. Marcus continued, “They are drafted on proper letterhead. They have interest rates and repayment schedules, but look at the lender.” He pointed to the top of the document. Holston River Holdings LLC. I have never heard of them.

I said neither had the Secretary of State until three weeks ago, Marcus said. He clicked a tab. This LLC was formed on February 26th. That is 2 days before your mother had her stroke. And who is the registered agent? Catherine asked, though she clearly already guessed the answer. It is a blind trust in Delaware, Marcus said. But the filing fee was paid by a credit card. He slid a bank statement across the table.

It was Rex’s personal Visa card. He created a shell company, Catherine said, her voice cold. He lent his own wife imaginary money from a company that didn’t exist yet. And now he is trying to pay himself back out of her estate. He is essentially washing the money.

He takes the cash from the estate to pay the debt, puts it into the LLC, and then withdraws it. It gets worse, Marcus said. He pulled up another document. This one was a deed. I recognized the address immediately. It was a small cabin near Lake City. Mom had bought it years ago as a rental property. It wasn’t worth millions, but it was worth at least $300,000. This is a quick claim deed.

Marcus said it transfers ownership of the cabin from Diane Sullivan to Holston River Holdings for the sum of $10. I looked at the date next to mom’s signature. February 28th. I read aloud. That was the day she went to the hospital. I said, “I pulled out my phone to check the timeline I had made. The ambulance came at 10:00 in the morning. She was unconscious by noon.” Marcus zoomed in on the signature block.

“Look at the ink,” he said. I leaned in on the screen. The difference was subtle but undeniable. The notary stamp and signature are in blue ballpoint pen. Marcus said the date is written in the same blue ballpoint, but your mother’s signature that is black gel ink and look at the pressure. He switched to a high contrast view.

When people sign a document, they rest their hand on the paper. It leaves microscopic indentations and oil smears. The notary signature has those. The date has those. The signature of Diane Sullivan does not. It floats. What does that mean? I asked. It means the signature was likely added later or the document was manipulated, Marcus said. But the biggest red flag is the medical record.

Catherine slapped a folder onto the table. I subpoenaed the hospital logs yesterday. She said on February 28th from 8 in the morning until she passed. Diane Sullivan was in the neuro. She was intubated. She was restrained. She was medically incapacitated, so she couldn’t have signed it.

I said physically impossible, Catherine said, unless the notary brought the book into the ICU, which the hospital visitor log says did not happen. So, he forged it. I said he stole the cabin, he stole the cabin, he fabricated the debts, and he is trying to liquidate the cash, Catherine summarized. And he used a notary to do it.

Who is the notary? I asked. Catherine looked at the deed. A woman named Linda Baker. I looked her up. She works at the same shipping store where Rex has a private mailbox. Catherine stood up and walked to the window. In estate law, we call this the metallic smell. She said, “You can smell the fraud because it is cold and hard and man-made.” Rex got greedy.

If he had just taken the cash, we might have had a hard time proving it was not a gift, but real estate. Real estate leaves a trail. To move land, you need a public record. And to create a public record, you need a notary. She turned back to us. We are done waiting. I am filing a motion to compel production of Linda Baker’s Notary Journal in Colorado.

A notary journal is a public record. If she refuses, she loses her commission. If she produces it, we catch them. Why, I asked. Because a journal logs the signer’s presence. Catherine said it logs the type of ID presented. It requires a thumbrint for real estate transactions. If mom was in a coma, she didn’t give a thumbrint. And if there is a thumbrint, it isn’t hers.

We filed the motion that afternoon. The reaction was immediate and violent. 2 days later, I was at home trying to sort through mom’s old emails when a courier arrived. This was not a sheriff. This was a private messenger. He handed me a letter on thick, expensive bond paper. It was from a law firm I didn’t recognize, not Arthur Vance. Rex had hired a real defense firm. Cease and desist.