HOA Karen Built 139 Vacation Cabins on My Lake — I Dropped the Dam Gates, Nature Did the Rest…

HOA Karen built 139 vacation cabins on my lake and she forgot to ask one tiny question. Who controls the water? I’m Evan McCrae, fifth generation steward of Lake Kestrel and the old stone lodge that watches over it. Sloan Whitfield, our platinum smiled HOA queen, decided my shoreline was her sandbox, slapped a forged plat on the county desk, and marched in the bulldozers.139 concrete slabs sprouted like mushrooms after rain. Cute decks, string lights, zero permission. Here’s what she didn’t know. My great-grandfather built Kestrel Dam to hold steady at 1838 ft, but it was engineered to rest perfectly safely at 1845 seven quiet feet. A legal easement, a physics lesson with receipts. When she pushed, I didn’t shout. I turned a wheel.

And Gravity did what Gravity always does calmly, relentlessly, without taking sides.

When people say don’t poke the bear, they usually mean don’t anger the person who can destroy you.

Sloan Whitfield never got that memo. Maybe she thought her pearl necklaces made her bulletproof or that her HOA letterhead carried more weight than a century of recorded deeds. Either way, the moment she filed that forged plat map with the county clerk, she started a war she couldn’t even spell. It began quietly like all bureaucratic crimes do.

One Tuesday morning, I got an HOA newsletter in my mailbox, though I’m not even part of their association. A glossy fullcolor piece of propaganda titled Exciting Expansion, the Kestrel Ridge Community Recreation Area. It had all the trimmings, digital renderings of a sandy beach, a volleyball court, kayak racks, and smiling families roasting marshmallows by my water. Only one problem. Their entire recreation area sat squarely on the northern cove.

my land, my title, my taxes, my lake bed. At first, I thought it was a typo. Maybe a new intern at their design firm got the coordinates wrong. I’m an engineer. I believe in data over drama. But when I pulled the county plat map and compared it with my own digital overlay, the line between our properties had mysteriously drifted hundreds of feet into my side.

clean, precise, just enough to claim about 50 acres of shoreline, including the gentle slope where my grandfather used to fish for base before the war. That’s when the alarms went off in my head. Boundary drift like that doesn’t just happen. Someone had paid a surveyor to redraw it. So, I called the name listed on the HOA survey, Grant and Howell Engineering, PLLC. No answer.

The voicemail was disconnected. I dug deeper. Old habits die hard when your ancestors were engineers and your idea of a hobby is auditing public records. Turns out the licensed surveyor who signed that map had lost his license 2 years prior for falsifying documents in a zoning dispute over in Asheville.

He wasn’t even allowed to submit paperwork in North Carolina anymore. That’s not an error. That’s fraud. I printed out everything. The deed chain going back to 1,923. the 1,976 sale records from when my great uncle sold the adjacent 1000 acres to pay estate taxes and my most recent GPS-based survey. Then I grabbed my Trimble rover, hiked the border, and shot new data points every 30 ft.

It took three days, two blisters, and one angry copperhead encounter, but by the end, I had a centimeter accurate model of my entire property line. When I overlaid the HOA’s forged map, the result looked like a magician’s trick. exposed a perfect deliberate shift of the boundary just subtle enough that most people would never notice.

I compiled it all into a 40-page report complete with timestamps, coordinates, and official county deeds. My lawyer, Sam Whitaker, read through it twice before leaning back in his chair and muttering, “Well, son, they just drew a line through your living room and called it theirs.” We sent a cease and desist letter the next morning.

Certified mail signature required. It was polite, but sharp enough to draw blood. Any further development or encroachment upon parcel has 74 to 283 shall constitute criminal trespass and civil fraud. The McCrae Trust asserts full ownership of the Lake Kestrel bed and shoreline under the riparian rights codified in deed book 122, page 41. I thought that would be the end of it. Most sane people would fold at the sight of legal precision.

But Sloan wasn’t sane. She was addicted to control. A week later, I found myself invited well summoned to the next HOA board meeting to clarify community concerns. I showed up in jeans, work boots, and a flannel shirt that still smelled faintly of hydraulic oil.

Their boardroom looked like the lobby of a mediocre country club mahogany veneer fake fern in the corner, a curig that hissed like it was offended to be there. Sloan sat at the head of the table, hair perfectly, sprayed smile perfectly fake. Beside her was a lawyer from Summitgate Communities, the developer backing her expansion dreams. Around the table sat five homeowners who clearly just wanted their pool passes and peace and quiet.

Mr. McCrae Sloan began all honey and venom. We understand you’re confused about the property lines. Our survey shows I cut her off. Your survey was submitted by a man who lost his license for falsifying county maps. That’s not confusion. That’s forgery. The room went still. One board member choked on her coffee.

Sloan blinked once, twice, and then smiled wider like a python, adjusting its jaw. Those are serious accusations, she said. They’re also true, I replied, sliding a copy of my report across the table. You’re trespassing. You have until Friday to pull your cruise off my land. She didn’t even look at it.

Instead, she held up her glossy map to the board like it was scripture. This, she declared, is the community’s lake. It’s in our name, our development plan, and our marketing materials. Mr. McCrae’s claims are unfounded. He’s simply unwilling to cooperate. Her tone had the smug finality of someone used to getting their way. The homeowners clapped politely, unsure whether they were applauding logic or lunacy.

After the meeting, I overheard her whisper to her lawyer, “He’s just some hermit up the hill. By the time he sues, well have it built.” And that’s when I understood her strategy. Delay, deny, and develop. She didn’t care about being right. She cared about being first. Once the land was altered, once the cabins were up, it would take years of litigation to undo it, and no judge would order the demolition of multi-million dollar community assets. She was gambling that I didn’t have the stomach or resources to fight.

That was her mistake. Within a week, bulldozers appeared at the cove. They tore through the old oaks my grandfather planted in 1948, flattening the slope like it was just another line item on a spreadsheet. I filmed everything from my porch date, time, GPS overlay. I even called the sheriff.

Deputy Carter showed up 20 minutes later, scratching his head under his hat. He looked at my official survey, then at the HOA’s flashy one, then back at me. “Sir, ma’am,” he said cautiously. “This looks like a civil dispute. Not really something I can arrest anyone for, which is law enforcement code for good luck in court.” Sloan smiled, that brittle, sun damaged smile of hers. “Thank you, officer. We appreciate your understanding.

” The next morning, I walked the edge of the damage. 50 acres of churned soil, broken roots, and shattered history. The air smelled like diesel and arrogance. I picked up a chunk of torn survey flag, theirs, not mine, and pocketed it as evidence. That night, I sat in my study surrounded by a century of blueprints, maps, and leatherbound ledgers from the McCrae family archives. My great-grandfather Colin had designed Kestrel Dam himself in 1928.

And his notes were obsessive handwritten calculations, contour sketches, rainfall records, even diary entries. That’s when I decided I wasn’t just going to fight her with lawyers. I was going to fight her with physics. But before I found the blueprint for revenge, I needed to understand the mind that built the trap in the first place.

And for that, I’d have to go deeper into the dam’s history, the family legacy, and the one clause in the deed that would make Sloan’s entire empire collapse under its own ignorance. The roar of diesel engines became my morning alarm. I used to wake to the sound of loons gliding over still water. Now it was backho and nail guns.

Within a month, the northern cove of Lake Kestrel looked like a construction zone straight out of a developer’s fever dream. Gravel trucks rumbled through my access road. Temporary power lines hung over trees like cobwebs. The HOA had officially broken ground on my soil. The sign went up first. The pinnacle cabins phase two of Kestrel Ridge.

A slick bronze and blue billboard featuring happy families clinking wine glasses by a lakeside fire pit. I couldn’t decide whether to laugh or throw up. Beneath the marketing gloss, the dirt told a different story. Illegally disturbed wetlands, mangled roots, tire ruts deep enough to swallow a kayak.

Sloan Whitfield was there every morning, perched in her white golf cart like a commander, inspecting the front lines. Her Escalade sat idling behind her with the engine running because apparently turning it off was beneath her. She’d point gesture and occasionally hold court with her entourage of contractors clipboard in hand. Her oversized sunglasses made her look like a bird of prey.

Every few days, I’d catch her turning in her seat to glare up at my lodge. That glare was pure challenge. I didn’t wave. I just lifted my camera. From my porch, I filmed everything. Datestamped, geotagged, archived. A small army of subcontractors moved with stunning speed. Foundations poured walls craned into place.

Prefab cabins arriving on flatbeds like boxes of cereal stacked side by side. Within 8 weeks, there were 139 of them cookie cutter luxury retreats lined up like teeth along the stolen shoreline. They weren’t shacks either. These were high-end vacation rentals. HVAC units, humming septic tanks, buried decks overlooking the lake I owned.

By my estimate, the project represented at least $12 million in unpermitted construction. I didn’t interfere. Not yet. I watched, I documented, and I planned. One evening, as I sat in the old study, flipping through my great-grandfather’s damn journals, I came across a weathered blueprint labeled flow regulation, upper spillway gate. Underneath he had written in neat cursive maintain operating elevation at 1838 ft for safety and aesthetics. Structural capacity confirmed at natural high water line 1845 ft 7 ft.

The words might as well have been written in gold. You see 1845 ft wasn’t some arbitrary number. It was the natural topography of the valley, the point at which the lake left unchecked would fill to its true shoreline. Every cabin the HOA built sat between 1839 and 1844 ft in elevation. In other words, inside the lake bed, they hadn’t built next to the water, they built in it.

And thanks to my ancestors meticulous engineering, I had every legal right to raise that water to its natural mark, so long as I followed damn maintenance protocol. Before I acted, though, I made sure every bolt and wheel still turned the way it should. At dawn, I hiked down to the dam, Kestrel Dam, named for the sharp-eyed birds that still nested in the cliffs above it.

The air in the dry gallery was cool and smelled of limestone and machine oil. Two massive iron wheel valves sat on either side of the tunnel, connected to the slle gates that controlled the outflow. Each one was as tall as my shoulders, its spokes worn smooth from a century of careful hands.

My father used to bring me here as a kid, letting me spin the wheel a quarter turn while explaining, “This is how we keep the valley safe, Evan. The dam listens, but it never forgets. That day, it listened to me again. I turned the valves just enough to feel the old gears engaged, testing their range. The motion was heavy, deliberate mechanical poetry.

When the indicators settled back at closed, I knew the system still worked flawlessly. Meanwhile, above ground, the HOA’s fantasy world was expanding. Sloan had begun advertising the cabins online. Lake Kestrel luxury cabins. Experience nature elevated. I nearly choked when I saw the tagline. Nature elevated. Yes.

Right up to 1 84 5 ft where I plan to let gravity do its work. But I wasn’t reckless. Before moving a drop of water, I needed to make my position legally unassalable. First, I pulled every piece of documentation I could find. The original dam maintenance manual, handtyped, bound in faded blue cloth.

the McCrae trust deed specifying flood easements and the hydraological inspection certificates renewed by my family over the decades. Each document confirmed what I already knew. Control of the water level for safety inspections and maintenance rested solely with the dam operator, me. Next, I called the state’s Department of Environmental Quality. I wasn’t reporting them yet. Instead, I asked a few theoretical questions.

If a private land owner owns both the dam and the lake bed, I asked the clerk and maintains riparian rights up to a documented high water mark, what’s the liability if temporary water level restoration damages unauthorized structures built within that easement? There was a pause, then she said cautiously.

If those structures were built without permits and inside a recorded flood easement, liability would fall entirely on the builders. Bingo. Still, I wasn’t going to tip my hand too early. The HOA’s lawyers were wellunded and endlessly slimy. If I gave them even a hint of what I planned, they’d run to court to block me.

So instead, I kept smiling at Sloan when I passed her at the general store, nodding like nothing had changed. Inside, I was counting days. By midsummer, all 139 cabins stood finished. They had power plumbing, satellite dishes, even potted ferns on the porches. A few board members hosted openhouse parties, taking selfies by the water.

Every time one of them posted on Facebook with the caption, “Our Lake Kestrel Paradise,” I saved a screenshot. Evidence: “One humid afternoon, I stood on the bluff with my binoculars watching a ribbon cutting ceremony at the main pier. Sloan was in her element microphone in hand, HOA logo behind her.

“This,” she declared, “is the crown jewel of our community, the lake that brings us together.” I almost laughed out loud. You could see it in her face, the smug certainty of someone who thought paperwork could rewrite physics. Her crowd cheered, champagne popped, and the mayor’s assistant snapped photos for the local paper. I just whispered, “Enjoy it while it lasts.

” Because what they called phase 2 was about to meet act three. That evening, back in my study, I drafted a letter with Sam, my lawyer. It was short, professional, and impossible to ignore. It read to the Kestrel Ridge Homeowners Association. This notice serves as formal communication from the Kestrel Dam operations office. In accordance with dam safety regulations and riparian maintenance rights established in deed book 122, the lake will be restored to its documented high water elevation of 1845 ft for routine inspection.

All property owners are advised to remove movable property from the designated flood easement zone by 900 a.m. 2 days from receipt of this notice. We sent it by certified mail to the HOA’s office and directly to Sloan’s address. I imagined her signing for it in her spotless foyer, rolling her eyes and tossing it in the trash. That was fine.

She didn’t need to believe me. Gravity didn’t care whether she believed or not. For the next 48 hours, I barely slept. I checked the weather forecast. Rain was on the way. Perfect. I prepped my GoPro cameras to record from multiple vantage points. One on the bluff, one near the shoreline, one inside the dam gallery.

Every lens would capture the slow, inevitable correction of nature’s balance. As dawn broke on the deadline, day mist curled off the lake like breath from a sleeping animal. The cabins looked almost peaceful lined up along the shore.

Workers were still inside, installing curtains, fluffing pillows, unaware that the real inspector was on his way, one who didn’t wear a badge or carry a clipboard. The inspector’s name was Gravity, and its report would be thorough. There’s a certain calm before you change the course of nature. It’s not silence exactly. It’s that low humming stillness that hangs in the air right before a thunderstorm.

That’s what the morning felt like at Lake Kestrel on the day everything shifted. From my kitchen window, I could see fog sliding over the water, soft and silver. The cabins, those perfect little boxes Sloan called her crown jewels, stood lined up like soldiers, awaiting inspection. They looked peaceful, even beautiful. If you didn’t know, they were built on stolen land and arrogance.

I poured myself a mug of black coffee and opened my grandfather’s maintenance log one last time. The entry from June 1,949 was underlined twice. Periodic structural test rays to natural elevation for 128 hours. All systems stable. He’d done it himself 76 years ago. The dam had survived floods, hurricanes, and the occasional bureaucrat. It would handle this just fine. At precisely 8:55 a.m.

, I drove my pickup down to the damn access road headlights cutting through the mist. My thermos rattled in the cup holder. The air smelled like wet pine and iron. I parked beside the service gate, grabbed my clipboard, and called. The county dispatch procedure was everything. “Morning,” I said, keeping my tone casual.

This is Evan McCrae, registered operator for Kestrel Dam permit Hass 894C. Commencing scheduled maintenance standards slow fill inspection to the natural water line. Not an emergency, just noting for record. The dispatcher hesitated. Copy that, Mr. McCrae. Uh, how long will the test last? 12 to 24 hours, depending on inflow, I replied. All downstream channels clear. Understood. Logging it now.

Good luck, sir. Perfect. I wanted that timestamp in their log books. Proof that this was procedure, not vengeance. Though between you and me, the line had blurred by then. Inside the dam’s dry gallery, the air was cool and thick with the scent of old stone and machine grease.

The twin cast iron wheels waited like ancient guardians, each connected by heavy drive shafts to the slle gates that controlled the lakes’s outflow. My flashlight beam caught the polished brass of the pressure gauges, still ticking faithfully. I laid a hand on the north gates wheel. It was cold and rough under my palm, as if the metal remembered every generation that had turned it before me.

“All right, old friend,” I whispered. “Let’s remind them who owns the lake.” It took nearly 15 minutes of steady cranking before the first groan echoed through the tunnel. Deep beneath my feet, steel shifted against stone, releasing a vibration I could feel through my boots. The sound wasn’t violent. It was patient, powerful, inevitable.

I repeated the process on the south gate, watching the indicator needles move from open toward maintenance position. Each rotation was a small act of rebellion. Each creek of metal was a century of inheritance coming alive. Outside, the effect was invisible, at least at first. The water’s surface didn’t boil or rush. It simply slowed.

The dam was holding more inflow than it was releasing, and slowly, almost imperceptibly, the lake began to rise. By noon, the first inch was measurable. My calibrated gauge rod near the shoreline confirmed at 1839 ft up from 1838 that morning. Nothing dramatic yet.

Even the herand still stalked the shallows, unaware that their hunting ground was about to move uphill. Around 1 130 p.m., I set up my spotting scope on the promontory behind my lodge. Through the glass, the cabins looked miniature like toys arranged along a bathtub. Workers were milling about, finishing touches, maybe wondering why the ground felt softer underfoot.

I made myself another coffee and kept watching. By 2000 p.m., the water had crept another half foot higher. It touched the edge of the newly rolled sodnons the HOA had so proudly installed. A few workers noticed. I could see them pointing phones out, maybe taking pictures to text to their supervisor. Nobody panicked.

Why would they lakes fluctuate right? By 315, the lowest cabins, those closest to the cove had puddles forming around their foundations. A foreman splashed through the mud, waving his arms. Through my scope, I saw the panic starting to ripple through the sight like wind over grass. And then, right on Q, the queen arrived. Sloan’s white escalade glided down the gravel road like a yacht cutting through fog.

She stepped out in a crisp linen outfit and platform sandals phone glued to her ear, gesturing wildly toward the water. Even from half a mile away, I could read her body language outrage mixed with disbelief. She thought it was a mistake. She thought she could fix it with a phone call.

I leaned on the railing, sipped my coffee, and murmured, “Try calling gravity Sloan. Let me know if it picks up.” The rain started an hour later, just a light drizzle, but it added to the inflow. By 400 p.m., the lake had reached 1842 ft. Water lapped against the concrete slabs of the first row of cabins. Wooden stairs bobbed loose.

A portable generator sparked and hissed before going dark. I could see people running now. Contractors shouting homeowners pointing Sloan yelling into her phone. The soundtrack was distant thunder and chaos. By 500 p.m. the first cabin went under. Water poured through its sliding doors like the world’s slowest avalanche.

Curtains fluttered once before, disappearing beneath the rippling surface. One down, 138 to go. Through all of it, I stayed calm. I wasn’t gloating. I was documenting. Every few minutes, I snapped photos through the scope, timestamps, elevation readings, precise visual records. If this went to court, I wanted everything airtight. Around 630, my phone buzzed.

Sheriff Carter, Mr. McCrae, he said, his voice weary. I’m getting reports of rising water levels flooding those new cabins. The HOA president saying, you’re deliberately causing damage. I notified dispatch of scheduled maintenance 12 hours ago, I replied evenly. Everything’s logged. The water’s still below the natural high water mark. Silence, then a sigh. You got documentation. Every bit of it.

Then sit tight, he said. I’ll come out there and take a look. When he arrived an hour later, his cruiser lights reflected off the swelling lake. He trudged up to my porch boots. Muddy rain dripping off his hat. Behind him, Sloan followed like an avenging angel with a ruined manicure. “He’s flooding us,” she shrieked. “He’s destroying community property.

Arrest him.” I handed Carter a folder thick enough to make a satisfying thunk when it hit his palm. Inside were certified mail receipts, the damn maintenance log, the 1,928 deed showing the flood easement, and the engineering manual highlighting 1845 ft as the safe operational limit. Sheriff, I said, keeping my tone calm, I’m performing a structural inspection under rights clearly established in county and state law. Those cabins are inside the easement zone. I gave 48 hours written notice. They chose to ignore it. He

flipped through the papers, squinting. Then he turned to Sloan. Did you get this notice? She hesitated. I I may have seen something, but it wasn’t. It was certified mail I cut in. Signed for by you. 942 a.m. 2 days ago. Carter’s eyebrow went up.

The wind carried the distant sound of cracking timber as another cabin wall buckled under the slow push of water. “Well, ma’am,” he said, shifting his weight. “Looks like this isn’t a criminal issue. More of a civil matter. Nothing I can do here. Sloan’s face went scarlet. Civil matter. He’s washing away our investment. He tipped his hat. Maybe next time, ma’am.

Check your elevation before you build in a flood easement. She sputtered, spinning on her heel shoes, sinking into mud. Her Escalade tires threw up water as she sped off toward the main road. By nightfall, the rain had stopped, but the lake held steady at 1 84 5 ft. The last row of cabins, those perched just above the rest, were now islands of wood and panic.

Porch lights flickered, then went black. The sound of frogs and crickets, returned eerily serene. I stayed awake until midnight, sitting by the window, watching the reflections of the submerged cabins shimmer beneath the moonlight. I wasn’t proud. I wasn’t ashamed either. I just felt balanced, like the lake had exhaled after holding its breath for too long. When the first light of dawn broke, a pair of kestrels soared over the water, circling lazily.

For the first time in months, the lake looked the way it was meant to, wide, calm, and unchallenged. That morning, I wrote one line in my journal. Sloan wanted a lakefront paradise. Now she’s got one right through her living room. And with that, the reckoning had officially begun.

By sunrise, the storm had passed, but its aftermath glistened across the lake like liquid truth. The mist was lifting, and beneath it the full extent of Sloan’s empire lay waterlogged and defeated. 139 luxury cabins, all perfectly aligned in their uniform hubris, now stood half drowned beneath the glassy surface of Lake Kestrel. The reflection was almost poetic mirror images of arrogance and consequence. The morning light revealed what the night had hidden.

Decks floated away like driftwood. Lounge chairs bobbed at odd angles. Mattresses had burst through cabin windows, waterlogged and heavy drifting lazily toward the dam. For years, Sloan had sent letters demanding that I respect community standards. Now her entire community was dissolving into the very water she tried to claim.

But while I stood at my window sipping coffee, the real waves were forming elsewhere in inboxes, phone lines, and emergency meetings. By 900 a.m., my phone began buzzing non-stop. local reporters, homeowners, even a panicked clerk from Summit Gate communities. The developer wanted to get my side of the story. I ignored them all, at least for now. There would be a time to talk, and it would be in front of a judge.

At 930, a White County pickup rolled up my driveway. Outstepped two people in rain gear, one from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, the other from the county’s floodplane administration office. They carried clipboards, cameras, and faces that said, “We heard about something big.” Mr. from McCrae.

The DEEQ inspector began shaking my hand firmly. We received multiple reports of unpermitted construction inside a riparian buffer. Are we correct in assuming that’s he gestured toward the drowned cabins the situation? You’re assuming correctly. I said they were built without proper permits inside a documented flood easement. I have all the paperwork.

For the next 2 hours, we walked the shoreline or what was left of it. I showed them the survey markers, the floodplane boundaries, the original 1,928 engineering schematics, and most importantly, the certified letter warning the HOA to vacate. They photographed everything, nodding as they went. When they reached the submerged cabins, one inspector shook his head and muttered, “This is going to be one hell of a report.

” Meanwhile, down at the main gate of Kestrel Ridge, chaos had erupted. Homeowners were gathering, shouting at the board, waving their phones like torches. Someone was live streaming on Facebook, captioned, “Our HOA president flooded us. I’d have laughed if it weren’t so tragic.” By noon, the local news van arrived. I could see it from my porch.

A red and white truck from Channel 7 antenna raised camera rolling. Reporters slogged through mud and rain boots, interviewing residents standing kneedeep in the mess. Sloan, of course, was there drenched, but still wearing her oversized sunglasses like armor.

She was gesturing wildly toward my lodge across the water, her voice carrying faintly through the morning air. He weaponized the damn,” she screamed. “He’s trying to destroy this community.” I smiled. Communities built on fraud destroy themselves. That afternoon, my lawyer, Sam Whitaker, drove up in his dusty sedan. He looked like a man, both exhausted and exhilarated. “Well,” he said, climbing out. “You’ve sure stirred up a hornet’s nest.

” “The developer already calling this an act of God.” “I suppose you’re the deity in question. Gravity’s the real god here,” I replied. “I just gave it permission.” He chuckled, then got serious. The DEEQ is already filing a formal notice of violation against the HOA. They’ll hit them with six figures in fines for environmental damage alone.

You couldn’t have planned it better if you’d scripted it. Oh, but I did plan it, I said. Every inch, every foot, every elevation line. He looked at me for a long moment, then nodded. You know, Evan, there’s poetic justice, and then there’s whatever this is. By late afternoon, county officials had taped off the access road to the cabins, citing unsafe conditions.

A few enterprising residents tried to reach their cabins by kayak, some even using pool floaties, but the sheriff’s deputies turned them back. Private property, Carter told them, pointing toward my lodge. And technically, he’s not wrong.

Inside her temporary command center, the HOA clubhouse, now doubling as a crisis bunker, Sloan convened an emergency meeting. Thanks to a friendly neighbor who recorded the entire thing on their phone, I got to enjoy the replay that evening. It opened with chaos, people yelling, chairs, scraping. One homeowner shouted, “You told us he was bluffing.” Another screamed, “My cabin’s under 8 ft of water.” Sloan voice, trembling, but still defiant, slammed a folder onto the table.

He manipulated the water level illegally. We’ll sue him for everything he owns. Someone from the back of the room shouted, “You said he couldn’t touch the lake. You said you owned it.” That’s when the first real crack appeared in her. Composure. She tried to regain control, waving her hands. We relied on the developer survey. It was legitimate.

A woman in a raincoat stood up holding her phone. The DEEQ just confirmed the surveyor you used lost his license for forgery two years ago. We’re done, Sloan. You’re done. The room erupted again. The HOA board voted right then and there to suspend her pending investigation. In HOA language, that’s code for you’re fired, but we’re pretending it’s polite.

That night, as the rainclouds cleared and the stars returned, I walked down to the dam. The water was still at its natural mark. 1 845 ft gleaming under moonlight. A few floating debris pieces drifted by a patio chair, a doormat that read, “Welcome to paradise.” And hilariously, a framed HOA Excellence Award 2022. I fished it out with a branch and leaned it against the damn wall. “Fitting trophy,” I said aloud.

Then I checked the gauges. Steady, perfect. The structure was fine, exactly as designed. Nature was balanced again. Over the next week, the floodwaters didn’t recede. They lingered slowly, methodically dismantling the cabins from within. Wood warped drywall collapsed, and mold spread like ink through paper.

Insurance adjusters arrived, took one look, and collectively sighed the sigh of men who know they’re about to deny a claim. I’d already anticipated it. The moment I saw one of their clipboards labeled pinnacle cabins claim review, I knew how the report would read. claim denied due to gross negligence, unpermitted construction within a documented flood plane, and failure to comply with state environmental codes. Within days, the developer stock tanked.

Local investors pulled out. Their social media pages were flooded, pun intended, with angry comments and screenshots of the sinking cabins. Meanwhile, the county attorney contacted me directly. “Mr. McCrae,” she said carefully, “you’ve been the subject of quite a bit of discussion at the courthouse.

We’ve reviewed your documentation and well, you were within your rights legally and hydraologically. Hydraologically, I repeated, smiling. That’s a first. She laughed softly. Let’s just say your dam is the only thing around here still holding. The fallout spread like ripples. Within 3 weeks, multiple lawsuits had been filed. Homeowners against the HOA, the HOA against the developer, the developer against their surveyor, and ironically, the surveyor now facing criminal charges against no one because he’d vanished out of state.

And me, I wasn’t named in a single suit. My notice, my documentation, my calm, methodical timing, they had turned what looked like vengeance into pure legal precision. Of course, public opinion didn’t need a courtroom to decide. The local paper ran the story under the headline, “Hoa ignored flood warnings, built cabins in easement, Lake Kestrel strikes back.

” They even quoted me from an interview I finally agreed to give. I didn’t flood their cabins. I simply returned the lake to where it belonged. Gravity doesn’t take sides, it just takes the shortest path. Sloan disappeared soon after. Rumor had it she moved to Florida, trying to reinvent herself as a property consultant.

I wish her the best, preferably somewhere above sea level. As for Lake Kestrel, it was quiet again. The Kestrels returned to their nests. The air smelled clean. And at night, when the moonlight rippled across the restored shoreline, I could almost hear my great-grandfather’s voice. The dam listens, but it never forgets.

Neither do I. By the second week, the town of Hawthorne Falls wasn’t talking about the weather or politics or even the high school football game. They were talking about Sloan Whitfield, the woman who built Atlantis. That’s what the newspaper called her after the drone footage went viral. 139. Shiny brand new cabins submerged like modern ruins beneath the mirrored skin of Lake Kestrel.

I didn’t post the video, but I sure didn’t stop anyone else from sharing it. Someone from Channel 7 had filmed the aerials, panoramic shots sweeping over the drowned community, the glittering water swallowing roofs and decks, Sloan’s half-colapsed pier poking up like a monument to arrogance. The footage hit a million views in 3 days.

The comment sections were a carnival of sarcasm. She should have read the fine print. You can’t outvote gravity. HOA equals humbled over again. Meanwhile, Sloan had gone into damage control mode. She called an emergency press conference at the Lakeidge Clubhouse, the one building still above water.

They decorated it with soggy bunting and folding chairs, trying to look professional. The irony was delicious. I didn’t attend, but someone live streamed the whole thing. I watched from my porch with a bourbon in hand. Good afternoon, she began wearing a navy blazer that couldn’t hide her exhaustion.

I want to assure all Kestrel Ridge residents that the board is taking immediate legal action against the individual responsible for the deliberate sabotage of our community. Her voice wavered on sabotage. Behind her, a handful of soaked homeowners looked unconvinced. A man raised his hand. You mean the landowner you ignored? The one who warned you? Sloan’s smile cracked. Sir, this is not the time.

Oh, I think it’s exactly the time. Another woman interrupted. You told us he couldn’t legally touch the water. You said the map was verified. The murmur spread. Phones went up. Camera zoomed in. Sloan’s press conference had officially turned into her trial. By the time it ended, half the HOA board had resigned on the spot.

2 days later, the HOA bank account, nearly drained by emergency contractor fees and pending lawsuits, was frozen under a court order. and the cherry on top. The developer Summitgate communities issued a public statement that threw Sloan straight under the bus. The HOA president acted independently and without proper authorization when commissioning the now invalid survey and initiating construction within a regulated flood easement.

Translation: We’re not paying for this. When Sami lawyer read it aloud in his office, he laughed so hard he spilled his coffee. That woman’s empire just dissolved faster than her lawn furniture. Still, I wasn’t gloating. Not entirely. There’s a strange melancholy that comes when you watch justice happen, not as vengeance, but as physics.

It doesn’t roar, it simply settles. That weekend, I drove into town for the first time since the flood. Normally, I keep to myself groceries, hardware, the occasional stop at the feed store. But this time, every person in Hawthorne Falls seemed to know who I was. At the gas station, the clerk, a kid barely out of high school, grinned as he handed me change.

You’re the guy from the lake, man. That video was wild. Guess Gravity went viral, I said. Even the sheriff waved when I passed him in his cruiser. Carter rolled down his window and shouted, “Hope the lake’s behaving itself.” “It’s better behaved than some people,” I shouted back. At the diner, folks offered to buy me pie and coffee.

It was friendly, sure, but also curious, reverent, in a small town way. They weren’t celebrating destruction. They were celebrating the idea that someone had finally stood up to an HOA bully and won. That night, I found an envelope taped to my gate. It was damp from due, handwritten in a shaky script.

Inside was a note from one of the older residents of Kestrel Ridge, Mr. McCrae. I just wanted to say thank you. We didn’t know what Sloan was doing. She told us it was all approved. My husband and I lost our savings in that cabin, but at least now the truth is out. Maybe next time we’ll ask better questions before following someone with a clipboard. Respectfully, Grace Howeran. I read it twice.

Then I tucked it into my journal beside my great-grandfather’s notes. Some people build monuments out of stone. My family built them out of consequences. Two weeks later, the DEEQ released its official report. It was brutal. Unauthorized construction within a protected flood plane. Violation of sediment control and buffer regulations.

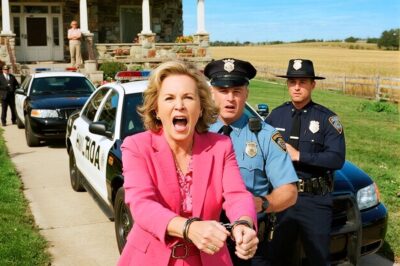

Negligent disregard for existing hydraological easements. Culpable parties. Kestrel Ridge HOA President SHA Whitfield. the fine $870 in environmental penalties non-negotiable. On top of that, the county attorney announced pending civil action for property damage to the wershed and unlawful modification of drainage infrastructure. Sloan was finished. The last time I saw her was in the parking lot of the county courthouse.

She was getting into her car flanked by two lawyers who looked like they’d rather be anywhere else. Her hair was disheveled, her designer heels caked in mud. For a moment, she saw me across the lot. We locked eyes. She didn’t speak, didn’t sneer, didn’t even glare.

Just a hollow look, a mixture of disbelief and humiliation. The kind of expression you wear when you finally realize that rules apply to you, too. I nodded, once polite as ever, then turned away. By autumn, the cabins had become a ghost story. The lake shimmerred higher than usual that season. Sunlight dappling over the submerged rooftops like coins at the bottom of a fountain.

Fishermen came from nearby counties just to see the drowned village. Kids in kayaks told each other that if you listened closely, you could still hear the hum of air conditioners beneath the water. Nature, of course, moved on. Ducks nested in the eaves of a half-sken cabin. Liies took root in what used to be driveways.

Herands perched on chimneys like sentinels. It was eerie, beautiful, and somehow fitting. Meanwhile, Summitgate quietly filed for bankruptcy protection. Their parent company rebranded under a new name, Blue Haven Developments. Same executives, new logo, same greed. As for the HOA dissolved, the state revoked its charter after the board failed to meet financial solveny requirements.

What was left of its treasury, mostly debt, was seized to pay partial fines. One afternoon, a county official knocked on my door with a clipboard and a smile. Mr. McCrae, I wanted to inform you that ownership of the former development zone has legally reverted to the McCrae Trust pending remediation. In simpler terms, the land was mine again.

It took me a long time to process that. The cabins, the shoreline, the laughter that used to echo off the hills. It all belonged to my family once more. But it didn’t feel like a victory parade. It felt like restoration, a return to balance. I hired a local salvage crew to start dismantling what was left above water. It wasn’t easy work.

Mold, warped wood, and twisted metal made the cleanup dangerous. Still, I insisted on being there every day. The crew thought I was crazy, but I wasn’t watching destruction. I was witnessing rebirth. At dusk, when the machinery fell silent and the lake glowed gold beneath the setting sun, I’d sit on the old stone bench my grandfather built and listen.

No motors, no shouting, no HOA meetings, just frogs, birds, and the steady whisper of water against rock. Some evenings, locals paddled by in canoes. They’d wave, sometimes shout a question across the water. You really flooded them on purpose. I just shrug. I didn’t flood anyone. I’d just let the damn breathe. They’d laugh, paddle off, and I’d go back to silence. Because here’s the truth. Sloan never understood.

You can’t own a lake. You can only respect it. Try to cage it, and it’ll eventually push back. And when it does, it won’t scream or rage. It’ll rise quietly, patiently, perfectly. By winter, the last of the cabins were gone, dismantled plank by plank.

The land was bare again, waiting for spring, waiting maybe for forgiveness. I ran my fingers along the old dam’s railing and whispered, “We did it, Granddad. We kept it safe.” The kestrels called overhead, circling their namesake lake. And for the first time in years, Lake Kestrel was truly free. Winter settled early that year, quiet and deliberate.

The air around Lake Kestrel turned crisp enough to make every sound carry the creek of the damn gate, the splash of a heron landing, even the faint rattle of ice forming along the reeds. After months of chaos, the silence felt earned. The headlines had faded. The lawsuits were crawling through court like lazy turtles.

And Sloan Whitfield’s name had become a punchline whispered over coffee at the diner. But for me, it was finally time to breathe. That’s the strange thing about revenge. It doesn’t end with fireworks. It ends with still water. The first snow came in early December, dusting the lake surface like powdered sugar.

I’d stand on my porch with a mug of coffee, watching the sunrise paint the ice pink and gold. From where I stood, you’d never know a small empire had drowned beneath that calm. Only when the light hit just right could you see faint outlines of concrete pads below the surface. Ghostly grids where the cabins once stood. Sometimes I’d think about what had driven Sloan. Maybe it wasn’t just greed.

Maybe it was insecurity. The need to turn control into proof of worth. Power can rot people faster than time. Still, I didn’t hate her. She’d built her own trap brick by forged brick. I just happened to own the trigger. The county eventually sent me the final settlement paperwork. The official letter head from the clerk’s office was almost anticlimactic.

This document certifies that parcels 174 to 283 ampers through 174 to 283 jewels previously occupied by the Kestrel Ridge HOA and its associated development are hereby transferred to the McCrae Trust as restitution for unlawful encroachment and damages. It felt strange seeing my name back on land my family had held for nearly a century before some slick developers map had erased it.

Restitution, they called it. I called it correction. Sam, my lawyer, came by that evening with a bottle of whiskey. To the quiet man who weaponized paperwork and water pressure, he toasted. I laughed. And to the attorney who made sure no one could call it a crime. He took a sip, then set the glass down. You know, Evan, I’ve been doing this 30 years.

I’ve seen petty wars over mailboxes, lawns, garden gnomes, you name it. But what you did? He leaned back in his chair. That was art. Cold measured lawful art. Art’s generous, I said. I just followed the blueprint, he smirked. Yeah, your great-grandfather’s blueprint and Newton’s. We sat for a while watching the ice form thin veins across the lake. The damn spillway hissed softly in the distance.

Somewhere out there, a lone owl called low and slow. After Sam left, I walked down to the damn gallery. one last time before the freeze. The metal smelled of rust and history. My flashlight swept across the machinery, silent now, but alive with potential. I ran my hand along the cold iron wheel, tracing the grooves worn by generations before me.

This place wasn’t just a structure. It was a chronicle. My family had poured sweat and stone into it. Every gear had a fingerprint, every bolt a story. I felt connected to them, to the land, to something older than both. outside the wind bit through my coat as I climbed up to the overlook.

From there, you could see the entire valley rolling hills, the frozen lake, the faint plume of smoke rising from my chimney. It was peaceful, almost too peaceful. That’s when I noticed a car parked down near the old access road. Silver, clean, out of place. It sat there for a while, engine idling, then the headlights cut off. A figure stepped out, bundled coat scarf, gloves.

Even from a distance, I knew the posture. shoulders drawn back in defiance, chin tilted just enough to pretend confidence. Sloan. For a moment, I wondered if I was imagining it a ghost, conjured by memory and regret. But then she stepped closer to the water’s edge, boots crunching on the frost. I didn’t move. I just watched. She stood there a long time, staring at the lake. Maybe she was looking for what she’d lost.

Maybe she wanted to see the reflection of what she’d become. The wind caught her scarf, whipping it sideways like a surrender flag. Finally, she spoke not to me, but to the air. You win, McCrae. Her voice carried thin and sharp against the stillness. You always did. Then she turned, climbed back into her car, and drove away. The tail lights disappeared down the road, swallowed by the trees.

I didn’t feel triumphant, just done. After that night, I never saw her again. Rumor had it she moved South Florida, maybe started a property consulting firm. The irony still makes me smile. I wish her well in a state that spends half its year underwater. Winter deepened. The lake froze solid by January.

The ice creaked under the weight of memory, and I let it. Some evenings I’d light a fire and read through my great-grandfather’s journals again. He’d written something I’d missed before, scribbled in the margin beside one of his engineering sketches. Man may build the dam, but water always decides the story. I closed the book and whispered, “You were right, old man.

” By February, the legal dust had settled. The county dropped all remaining investigations against me. The DEEQ even sent a letter thanking me for maintaining historical hydraological integrity. Fancy words for thanks for not blowing up the valley. But there was one last loose end. The cabins themselves. What? The water hadn’t destroyed the winter wood.

Still, I couldn’t leave them there. They were scars. So, I contracted a salvage company from Asheville. They brought in divers, cranes, and a whole lot of determination. The work took months. Every piece of rotted lumber, every twisted metal beam, every drowned appliance was hauled out, sorted, and either recycled or scrapped.

“The crews cursed the cold, but they couldn’t stop admiring the view.” “Hard to believe anyone tried to turn this into a resort,” one worker said, shaking his head. I smiled. “People mistake beauty for profit all the time. When they were done, what remained was pure again. The shoreline sloped gently, just as my great-grandfather had designed it.

The soil, freed from the weight of arrogance, drank in the snow melt. Spring would bring wild flowers. I knew nature was good at healing when left alone. By March, the county installed a new sign near the public road, Kestrel Lake preserve, managed by the McCrae Trust. No unauthorized construction. No exceptions. The first day that sign went up, someone left a bouquet of wild daisies at its base.

No note, just flowers. It made me think of Grace Howerin’s letter, the woman who lost her cabin but thanked me anyway. Maybe she’d left them. Maybe it was someone else who understood that sometimes justice looks like destruction before it looks like peace. On the first warm evening of spring, I rode my grandfather’s old canoe to the center of the lake.

The sun was sinking, turning the water into fire. I looked down at the rippling reflections and saw only sky. The cabins were gone, the damage erased. I dipped my paddle and whispered, “All debts paid.” The lake answered in silence as it always did. And for the first time since the whole nightmare began, I realized the story wasn’t about revenge.

It was about stewardship, about knowing when to fight and when to let nature handle the verdict. The dam stood steady behind me, its stones glowing orange in the dying light. My family had built it to last a century. I intended to make sure it lasted another. That night before heading inside, I turned once more to the water and said softly, “Rest easy, Lake Kestrel. You’ve earned it.

” Spring didn’t just bring birds back to Lake Kestrel. It brought subpoenas. The legal weather front arrived as a stack of envelopes so thick my mailbox leaned like a tired mule. I wasn’t the target. I was the map everyone needed to explain how they’d driven off the cliff. Homeowners sued the HOA. The HOA sued the developer.

The developer sued the surveyor. The surveyor still vanished. Was sued by the state. It was illegal oraoros. Everyone swallowing their own tail round and round. Sam, my lawyer, spread the paperwork across his conference table like a general analyzing terrain. Discoveries where truth crawls out, he said, tapping a folder.

Let’s make sure it finds its way to daylight. I was subpoenaed as a factual witness in three separate cases. I didn’t mind. I’m a hydraologist. I like neat stacks of data and questions with verifiable answers. Courtrooms, when they do their job, are just laboratories with wood paneling.

The first deposition took place in a beige room that smelled faintly of coffee and defeat. Across from me sat the developers council’s slick hair, slicker smile. He tried to make the whole thing sound like a misunderstanding. Mr. McCrae, he said, voice syrupy. Isn’t it true that water levels on a lake naturally fluctuate? I kept my face calm. Yes. Which is why your clients should not have built inside a recorded flood easement. And you raised the water intentionally.

For a scheduled maintenance and structural inspection as allowed in the deed, you never bothered to read, he shifted. But you knew it would damage the cabins. I knew the lake would rise to 1845 ft. The natural shoreline your cabins were inside of.

The damage came from building in the wrong place, not from water behaving like water. Even the court reporter smothered a smile. The real fireworks detonated during discovery. Emails surfaced shaky, angry, unmistakable. A junior project manager at Summit Gate had written elevation checks show several pads inside probable flood contour. We need confirmation on easement.

The reply forwarded by Sloan was colder than January proceed. HOA will manage optics. Another thread from the developer risk analyst warned surveyor’s license history is concerning. Recommend second opinion. the reply. Too late. Marketing launched. Sam slid the printouts across his desk to me. They knew, he said softly. They absolutely knew.

In the homeowner’s class action, I sat through opening statements on a rainy Tuesday. The plaintiff’s attorney, a woman with a voice like a church bell and a spine of tempered steel, stood before the jury and told the story clean. They didn’t just build cabins. They built a lie.

They dismissed warnings, sidestepped permits, and gambled with other people’s savings, knowing full well a lake rises to its shoreline. This case is not about a storm. It’s about hubris that met physics. When the HOA’s turn came, their new interim president, a mild man with accountant energy, looked like he wanted to apologize to every person in the room. Instead, he read a prepared statement about misplaced trust.

The jury looked back at him the way a parent looks at a child who has painted the dog. But the day that etched itself into my memory came courtesy of a forensic document examiner with the state. She testified about the forged plat map, the pressure inconsistencies in the stamp, the copied signature pixelation, the backdated notary seal.

Then she uttered the line that hushed the gallery. This map is not just inaccurate, it is counterfeit. If a lake could smile, Kestrel did. Meanwhile, insurance adjusters slithered through proceedings with the dry precision of calculators. Their findings were brutal and simple. Claim denied gross negligence.

Construction in a flood plane without permits. Failure to heed documented warnings. They used my certified letter as exhibit A. Sloan had signed for it. Blue ink, looping her name like a signature on a treaty. She’d broken it within a day. When it came time for my testimony in the HOA versus developer suit, Sam prepped me like a boxing trainer. Short answers, facts only, no sermonizing.

Gravity already preached the sermon. On the stand, I described the dam’s design, the natural high water mark, and the maintenance protocol older than most of the attorneys in the room. The developers council tried to make me sound like a villain with a valve. Mr. McCrae, you’ve admitted you turned the gates.

I adjusted the gates to maintenance position precisely as the dam manual instructs. You knew the water would rise. I knew the lake would return to its natural shoreline. That knowledge is literally how dams keep people safe. He paced. But you timed this with a rain event. I didn’t blink. Yes, the manual requires observing performance under realistic inflow.

If your client had not placed structures in the easement, the observation would have been uneventful like it had been for 97 years. A few jurors scribbled. One just nodded slowly like a man finally solving a stubborn puzzle. Back in Hawthorne, false consequences multiplied like springnats. The state levied $87 0 in environmental penalties against the HOA and separate fines against the developer for buffer violations.

The county rescended all permits retroactively and referred the forged plat to the district attorney. Rumors swirled about a clerk’s cousin who had expedited filings for a fee. An internal investigation confirmed it. The cousin resigned before the ink dried. As the legal structure came apart, people did what people do. They looked for a story that made them feel less foolish.

Some homeowners blamed Sloan exclusively. Some blamed the developer. A brave few stood in the mirror and said I should have asked harder questions. Those were the ones I respected most. One evening, Grace Howeran, the woman who’d written me that letter, showed up at my gate again. This time, she wasn’t carrying daisies. She brought a thermos and two tin cups.

We sat on the stone bench over the water. “You ever regret it?” she asked finally, raising the lake. I considered. No regret is wishing I hadn’t defended the truth. I don’t have that. I do wish none of it had been necessary. She took a sip. It was, she said simply. Some of us needed the water to tell the truth louder than the brochures.

By midsummer, verdicts arrived like distant thunder. The jury and the class action awarded damages to the homeowner’s partial restitution clawed from Summitgates carcass and what remained of the HOA’s insurance writer. The judge’s written opinion was surgical.

The defendants elected to proceed upon a knowingly unstable foundation, legal, hydraological, and ethical. When the lake rose, it was not an act of malice, but of equilibrium. Sloan’s personnel fate came last. The state brought a narrow criminal case, filing a false instrument, and conspiracy to defraud. She took a plea probation, a fine restitution payments that would outlast her escalade.

The day of the plea, she walked past me in the courthouse corridor without meeting my eyes. The pearl necklace was gone. So was the crown no one had ever given her. I thought that was the end of it until the county called one more meeting. This one in the largest room at the civic center.

A new slate of neighborhood leaders, developers, and landowners gathered to adopt what the agenda called best practices for shared waters. I stood in the back content to be an observer. The chair recognized a motion from a retired Navy engineer named Ray Dalton, the kind of man who measures twice and then measures two more times for luck. He read the proposed rule in a steady baritone.

Any HOA or developer seeking to modify or benefit from property it does not own must obtain one a vote of at least 2/3 of affected residents. Two, an independent engineers report covering hydrarology drainage and flood plane impacts and three written verification from the county and state environmental office prior to any ground disturbance. people murmured, nodding.

No buzzwords, no loopholes, just sanity with a map. Someone from the audience turned and said, “We should name it after the folks who taught us the lesson.” The chair smiled. All in favor of adopting the Dalton McCrae rule. A sea of hands rose. The motion carried. Not applause agreement. A community remembering the shape of common sense. After the meeting, the county attorney cornered me with a ry grin. “You realize you’ve become a case study,” she said.

We’re adding your damn protocol to the training binder. Happy to donate the template, I said. Prefer not to donate the sequel, she laughed. Let’s hope we never need one. That night, I walked the shoreline. New grass, brushing my boots. The cabins were gone. The birds were back.

The only lights along the water were stars and the patient lantern of the moon. I thought of my great-grandfather bent over his drafting table, drawing the line at 1 84 5 ft, not as a threat, but as a promise. this far and no farther. I thought of Sloan and how power without humility is just a costume. And I thought of Grace and the others who had lost money, pride, or both. How some wounds close cleaner when washed.

A breeze lifted across Lake Kestrel, carrying the scent of pine and silt and rain. The dam stood behind me old and steady, listening like always. Equilibrium, I said aloud, letting the words settle on the water. Out on the dark surface, a fish rose and vanished rings widening, wider than gone. consequences, then quiet, law, then balance. In the end, the lake had not taken sides. It had taken shape.

Summer rolled in gently like a sigh after a long argument. The lake had finally found its stillness again, glass smooth in the mornings, silver blue by dusk. From my porch, I could hear frogs returning to the wetlands that had been buried under construction gravel the year before. Dragonflies skimmed over the water, tracing tiny figure8s in the humid air.

The destruction had passed, but what comes after justice is always the harder part, restoration. It was time to heal the scars. When the courts handed full ownership of the Northern Cove back to the McCrae Trust, they also ordered the removal of any remaining debris from the defunct HOA development.

The county had allocated a small grant for environmental remediation, but the real work, what mattered, was personal. I didn’t want that land to be a graveyard of someone else’s arrogance. I wanted it alive again. So I called an old college friend, doctor Maya Torres, a landscape ecologist who’d spent the last decade restoring wetlands across the Carolas.

She picked up on the second ring. Maya, I said, you still good at turning messes into meadows? She laughed. Depends on how big the mess is. 139 cabins worth. There was a pause, then a whistle. Damn, Evan. What did you do on Leash Poseidon? Close enough. She arrived a week later in a dusty Subaru, wearing work boots and a grin. So this is your famous lake? She said, shading her eyes as she looked out at the water.

The one that ate an HOA. That’s the one. Maya walked the shoreline for hours. Notebook in hand, muttering to herself in the language of scientists and saints. Sediment gradients good. Invasive reed patches but recoverable. Oh, this slope could be perfect for wetland grasses. By sunset, she had a plan. We’re going to give this lake its lungs back, she said. Native grasses, black willows, red maples.

You’ll have herand nesting here by fall. Herands are already back. I said they beat you to it. The next few months turned the northern cove into something between a work site and a symphony. Local volunteers showed up retired farmers, high school kids earning service hours, even a few exhaeds. The first day, one of them, a man named Tom Brennan, hesitated before shaking my hand.

I was one of the folks who clapped for Sloan at that meeting, he said quietly. Didn’t realize we were clapping our way into quicksand. Figured I owed the lake some labor. I nodded. Welcome aboard. Just don’t clap this time, Dig. By mid July, the air buzzed with the sound of shovels, laughter, and the occasional curse when someone stepped into mud up to their knees. We planted willows near the low banks and switchgrass along the flood line.

Maya taught everyone how to anchor root balls properly, explaining how each species would hold the soil filter runoff and rebuild the natural buffer that had been bulldozed for Sloan’s recreation area. I filmed it all time-lapse footage that showed brown scarred earth slowly greening day by day.

When the last sapling was in the ground, Maya wiped her hands on her jeans and said, “Give it one good season. You won’t recognize this place.” She was right. By September, the slope that had once held rows of identical cabins was now a patchwork of green and gold. Wild flowers exploded across the meadows. Coropsis, cone flowers, aers, frogs croaked at dusk.

Deer crept cautiously through the new growth. Nature didn’t just forgive. It thrived on second chances. I kept working on the dam, too, running full inspections and repainting the safety rails that my great-grandfather had installed in the 1,920 seconds. The state sent an engineer to verify its structural integrity. After two hours of measurements and nodding appreciatively at the masonry, he said, “Mr.

McCrae, I’ve seen modern dams built with twice the budget and half the brains. This one could outlive both of us.” “That’s the idea,” I said. Later that month, the county hosted an official ceremony to mark the restoration. They called it Lake Kestrel Renewal Day. The irony wasn’t lost on anyone. A banner hung across the park entrance from flood to future. A community reborn.

The mayor gave a speech about resilience and learning from mistakes while the local news station aired drone shots of the new shoreline. They even asked me to say a few words. Public speaking isn’t my thing. But when the microphone was handed over, I didn’t read from notes. I don’t have a lot to say, I began. Except this water remembers. It remembers the path it’s supposed to take.

And it remembers who respected that path and who didn’t. My family didn’t build this lake to own it. We built it to understand it. The moment we start treating nature like property instead of partnership, it stops asking permission. Applause rippled through the crowd, not loud, but real.

After the ceremony, Grace Howerin approached with her husband, both wearing mudstained work gloves. “We planted 50 trees,” she said proudly. “Feels like we’re finally making something right.” “You already did,” I said. “You showed up.” Later that evening, as the crowd thinned and the light faded, Maya and I stood on the dock, watching the reflection of the new trees ripple in the lake.

You know, she said there’s a certain poetry in how this ended. The same water that wrecked those cabins is feeding new roots. Poetry or karma? I said, “Maybe both,” she smiled. “You think Sloan ever looks at this place online?” Maybe, I said. If she does, I hope she sees what the lake looks like when it’s respected.

That fall, the county wildlife board reported something that made me laugh out loud. A pair of bald eagles had nested near the restored cove, the first sighting in decades. The local paper ran the headline, Lake Kestrel welcomes its namesake.

That article stayed pinned on my fridge for months, not as a trophy, but as a reminder that sometimes the best revenge is a flourishing ecosystem. As winter approached again, the lake took on that quiet, glassy calm. I’d walk the new shoreline trails, gravel paths winding through young saplings, and think about how easily everything could have gone differently.

If I’d let anger steer instead of patience, if I’d flooded recklessly instead of methodically. If I’d sought destruction instead of proof. But patience had paid off, just like gravity. Steady, deliberate, unstoppable. One evening, as the sun melted behind the hills, I found a small wooden sign someone had nailed to a post near the water. It read, “Respect the lake. It doesn’t forgive ignorance.

No name, no signature, just truth. I stood there for a long time, listening to the gentle lap of waves against the rocks. The air smelled of pine and new soil. In the distance, a group of kids laughed, their voices echoing across the water as they skipped stones. For the first time since this whole mess began, I didn’t see wreckage or lawsuits or arrogance. I saw balance.

Maya was right. You wouldn’t recognize the place now. The lake had taken back its shape and in doing so given the town a new one. Sometimes the best way to fix something broken isn’t by fighting harder. It’s by letting the natural order finish the argument. I walked home as dusk fell passing the old bench where my grandfather used to sit.

The air was still the dam humming faintly behind me. The trees whispering their slow applause. Lake Kestrel was alive again, not as a symbol of revenge, but of restoration. A year passed before I realized how quiet life had become. No more letters on HOA stationery. No more lawyers circling like buzzards.

Just the slow rhythm of days shaped by light and water mornings filled with mist afternoons, heavy with the scent of pine evenings where the lake mirrored the stars so perfectly you couldn’t tell where heaven stopped and earth began. Some people think peace feels like victory. It doesn’t.

It feels like exhaling after holding your breath for too long. The world had moved on from the lake that ate the HOA. But every now and then, someone still found a reason to drive up my gravel road. Reporters, students, even county engineers all wanted to see the dam that taught a lesson. They expected spectacle.

What they found was quiet competence, an old stone structure, oiled gears, clean spillways, and a man who kept notes instead of grudges. In the spring, the county invited me to speak at the University of Asheville’s environmental law symposium. I nearly said no. I’m not much for podiums. But Sam, my lawyer, convinced me. You’ve already told the story once with water, he said. Might as well tell it with words.

So, I stood before a room full of professors, students, and bureaucrats. I didn’t use slides. I just told them what happened, plain and unpolished. I didn’t win because I had better lawyers. I said, I won because the facts were older than all of us. The lake existed long before the bylaws, and it’ll exist long after. Water doesn’t care about signatures.

It cares about gravity pressure and the arrogance of those who forget either. When I finished, the room was silent for a moment. Then came applause, not loud or flashy, but solid. One of the professors came up afterward and asked if he could include the Lake Kestrel case in his curriculum on environmental justice. I told him to go ahead, but to remember one thing. Don’t make it about revenge. Make it about respect.

That summer, the county officially designated the Northern Cove as the Kestrel Conservation Preserve, protected under local ordinance. It wasn’t my idea. It was Grace Howerins. She spearheaded the petition with a group of former homeowners who decided to turn remorse into stewardship. When she brought me the signed paperwork, she said, “We built on arrogance once. Now we’re building on gratitude.” I smiled.

That’s a much stronger foundation. We hosted the dedication in June. Families came with picnic baskets, kids chased butterflies, and the mayor unveiled a bronze plaque mounted on a granite stone near the trail head. It read, “The Dalton McCrae rule, adopted in 2025 to ensure no community may alter land or water without collective consent and scientific review because you can’t vote against gravity.

” The crowd laughed softly at that line. It had become something of a local proverb. Even the mayor used it whenever council meetings got heated. After the speeches, I wandered down to the shore. The sun was setting behind the ridge, casting long golden streaks across the lake.

The reflection of the young trees shimmered in the ripples, each one planted by hands that had once been part of the problem. The circle had closed. “Beautiful, isn’t it,” Maya said, coming up beside me. She’d stayed on as the project’s lead ecologist, and now spent her weekends teaching kids about wetland ecosystems. “Better than I dared hope,” I said. “You ever miss the fight?” she asked.

I thought about it for a long moment. No, I said finally. The fight was just noise. This is music. We stood there in silence, watching a heron glide low over the water. Later that evening, I sat on the porch of the old stone lodge with a journal in my lap, the same one where my greatgrandfather had scribbled notes about floodgates and elevation lines. I opened to the last page and began writing my own entry. The dam still stands.

The water still listens. The people finally do, too. I paused, then added, “Justice doesn’t always roar. Sometimes it just rises quietly until it finds its level.” When I closed the book, I felt something I hadn’t in years contentment. Autumn came early that year. The trees turned crimson and gold, their reflections rippling across the calm water.

The first frost painted the reed silver. One morning, as I walked the shoreline trail, I saw a new wooden bench overlooking the water. Someone had carved a single sentence into the back rest. May we always remember who owns the lake. There was no signature, but I didn’t need one. Everyone around here knew what it meant.

That winter, the county featured Lake Kestrel in a regional tourism video, though tourism isn’t quite the right word. They called it a story of consequence turned conservation. It showed drone footage of the restored shoreline, the wildlife returning the dam steady and strong.

The narration ended with a simple line, “At Lake Kestrel, nature didn’t take revenge, it took balance.” The video went viral again, but this time for all the right reasons. A few weeks later, I received a handwritten letter from a homeowner association president in another county. It began stiffly like a man unused to humility. Mister McCrae, I was one of those who laughed at your story when it first made the rounds.

I thought it was an exaggeration. Then our board almost made a similar mistake trying to reroute a creek for landscaping. Your story stopped us. We did the study first. Turns out we would have flooded our own clubhouse. Thank you. I pinned that letter above my desk. Sometimes prevention is the quietest victory of all. By the time the next spring arrived, the new willows had grown taller than me.

Their branches danced in the wind, whispering against the surface of the lake. I like to think they were saying thank you. That evening, as dusk fell, I walked to the dam one last time before locking up the maintenance hatch. The wheels gleamed with fresh oil. The gauges sat steady at 1838 ft.

Everything was balanced exactly where it should be. I stood there for a while, hand on the railing, watching the spillway trickle down into the valley below. The sound was steady, ancient, honest. I thought of my ancestors, the men who built this dam by hand, who poured stone and faith into its walls. They’d known that control was temporary, but care was eternal.

As stars began to appear overhead, I whispered to the water, “You and I did, good old friend.” The breeze stirred rippling across the lake as if in reply. When I turned to leave, I felt lighter than I had in years. The fight, the fury, the endless tug between arrogance and accountability. It was over. All that remained was the lesson clear as moonlight.

You can build walls, bylaws, and false maps. But the truth always finds its level. The damn stood behind me, solid and eternal. And somewhere out in the dark, a kestrel cried a sharp, defiant note that echoed across the valley. And in that sound, I heard everything the past forgiven. the present balanced and the future warned.

Because some lines can be redrawn on paper, but others, like the edge of a lake, are written by nature itself. That’s the story of Lake Kestrel. The story of a family that built with stone, a woman who built with lies, and a man who simply turned a wheel. And if there’s one thing this whole saga taught me, it’s this. You can argue with people.

You can even argue with courts, but you can’t argue with gravity.

News

Karen LOSES HER MIND After I Buy a House Outside Her HOA — Ends Up in HANDCUFFS on Live Camera! The first thing I heard was her voice, sharp enough to cut the morning air like a blade.

Karen LOSES HER MIND After I Buy a House Outside Her HOA — Ends Up in HANDCUFFS on Live Camera!…

HOA Tore Down My Fence Without Permission, Now They’re Paying $50,000 in Legal Damages… I knew something was off the second I pulled into my driveway and saw the pile of lumber where my fence used to be.

HOA Tore Down My Fence Without Permission, Now They’re Paying $50,000 in Legal Damages… I knew something was off the…

HOA Built Gate Across The Only Route to My Property… So I Bought Their Access Road… They built a gate across the only road that led to my property.

HOA Built Gate Across The Only Route to My Property… So I Bought Their Access Road… They built a gate…

I Just Moved In and the HOA Immediately Showed Up Demanding My Land — They Regretted Messing With Me… I never thought freedom would sound like gravel crunching under my tires, but that’s exactly what it felt like the day we pulled our trailer onto 20 acres of untouched Arizona land.

I Just Moved In and the HOA Immediately Showed Up Demanding My Land — They Regretted Messing With Me… I…

CH2. What Germans Really Thought About Canadian Soldiers in WWII? The first time many German soldiers heard the word Canadier, it seldom came from an intelligence report or a briefing from the high command. It came instead as a quiet remark in a trench,

What Germans Really Thought About Canadian Soldiers in WWII? The first time many German soldiers heard the word Canadier, it…

CH2. “Close Your Eyes,” the Soldier Ordered — German Women Never Expected What Happened Next…

“Close Your Eyes,” the Soldier Ordered — German Women Never Expected What Happened Next… Imagine expecting monsters but finding mercy….

End of content

No more pages to load