“You’re Not Stealing from Us?” — Austrian Farmer Meets Occupying American Troops…

It’s May 7th, 1945. A farming family in the small Austrian village of Salfeldon, about 50 mi south of Saltsburg, huddles in their cellar. Upstairs, they can hear engines, American engines. The father, we’ll call him Ysef, a name common enough in rural Austria, grips his wife’s hand. Their two daughters, ages 8 and 12, are crying quietly.

Joseph’s mother, 67 years old, prayed the rosary in the corner. For 6 years, Joseph has heard the same message from every newspaper, every radio broadcast, every party official who passed through town. The Americans are coming, and when they arrive, they will destroy everything.

They’ll burn farms, rape women, execute civilians, loot everything that isn’t nailed down. The folks storm, the desperate lastditch German militia has already retreated through the village two days ago, blowing the bridge over the Salak River as they left. The Americans are maybe 200 yards away now. Joseph made a decision yesterday.

He buried the family’s valuables, his wife’s jewelry, what little money they had saved, the silver candlesticks from his grandmother in a wooden box under the chicken coupe. He slaughtered their last pig and hid the meat in the root cellar covered with hay. If the Americans are going to take everything, he reasoned, at least they won’t find it all.

What Ysef doesn’t know, what 6 years of Ysef Gerbal’s propaganda machine has made impossible for him to know, is that the American soldiers rolling into his village right now are more likely to give his daughters chocolate than harm them. that the US Army has strict rules of engagement regarding civilian property, that American military police will actually arrest GIs who loot, that within 48 hours, American medics will be treating Austrian civilians for free in a field hospital setup in the village square. This is the story of what happened when Nazi propaganda met

American reality. And it starts with one simple question that Joseph will ask a US Army sergeant in about 20 minutes. A question so stunned, so genuinely confused that the sergeant will remember it for the rest of his life. Let’s back up 6 months. By November 1944, the Third Reich is collapsing.

The Red Army is smashing through Poland toward Germany’s eastern border. The Western Allies have liberated France and are pushing toward the Rine. for Austrian civilians and Austria has been part of Hitler’s Germany since the Anelus in 1938. The question isn’t whether Germany will lose. The question is who will occupy them when it’s over. Gerbles understands the fear factor perfectly.

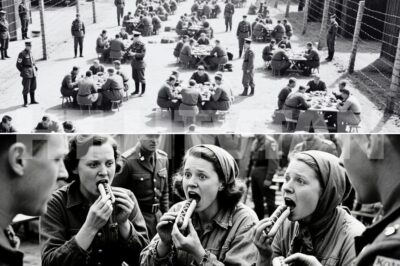

His propaganda ministry has been preparing the German and Austrian population for this moment since 1943. The message is simple and repeated constantly. The Americans and British are bad. The Soviets are worse. But all of them will brutalize you if given the chance. The propaganda isn’t subtle. German newspapers print stories completely fabricated about American soldiers executing German prisoners.

Radio broadcasts describe American bombing raids as terror attacks designed to kill civilians. Posters show American soldiers as savage beasts. One poster distributed widely in Austria in early 1945 shows a learing American GI with a knife standing over a cowering German family.

The caption reads, “This is what awaits you.” For civilians in Western Austria, there’s a calculation happening. The Red Army is advancing from the east. The Americans are coming from the west. The Soviets have a reputation, a deserved one, for extreme brutality.

German refugees fleeing westward from Prussia and Sisia bring stories of Soviet atrocities, mass rape, summary executions, entire villages wiped out. So, here’s the twisted logic. Maybe the Americans will be slightly less terrible than the Soviets, but they’ll still be terrible. This is what Joseph believes as he sits in his cellar on May 7th, 1945. The engines stop. Joseph hears boots on the ground. Heavy boots. American boots.

His wife squeezes his hand so hard it hurts. The 12-year-old daughter has stopped crying and is just staring at the cellar ceiling, listening. Then, a knock on the door. Not a bang, not a boot kicking it in. A knock. A voice speaking German with a thick American accent. Hello? Anyone home? We’re American Army.

We’re not going to hurt you. Ysef freezes. This isn’t what he expected. Gerbles told him the Americans would smash down the door. They’d storm in with guns. They’d drag his family out. And another knock. Sir, ma’am, we know you’re in there. It’s safe to come out. Joseph looks at his wife. She’s shaking her head. Don’t go up there.

It’s a trick. The 67year-old grandmother has stopped praying and is staring at him. Joseph makes a decision. He stands up, his legs unsteady. He climbs the cellar stairs. His hand is on the door handle. He can hear men talking outside in English. He doesn’t speak English. For all he knows, they’re discussing how to break in. He opens the door.

Standing on his porch are four American soldiers. They’re not pointing guns at him. One of them, a sergeant, based on the stripes on his sleeve, is holding a pack of cigarettes. Another has a chocolate bar in his hand. They look tired, dirty, but not savage, not brutal. They look like guys who’ve been walking for weeks and just want to sit down.

The sergeant in his broken German says, “Good morning, sir. We need to search your house. Check for German soldiers. You understand?” Joseph nods. Can’t speak. The words won’t come. The Americans walk past him respectfully, not shoving, and begin searching the house. They’re not smashing furniture. They’re not grabbing things.

They’re just looking, opening doors, checking rooms. One of them finds the seller entrance and calls down in German. It’s okay. Come up. You’re safe. Joseph’s wife and daughters emerge. The grandmother follows. They’re all staring at these American soldiers like they’re aliens from another planet. The search takes 5 minutes. No German soldiers hiding, no weapons.

The sergeant nods to Joseph. Thank you for cooperating. Do you need anything? Food, medical supplies. Joseph just stares at him. Then he asks the question. The question that will haunt him, that will make him realize just how thoroughly Gerbles lied to him. You’re not stealing from us? The sergeant laughs, not cruy, just surprised. No, sir. We’re not stealing from you.

One of the other soldiers, the one with the chocolate bar, walks over to Joseph’s daughters and hands it to them. For the kids, he says in English, the 8-year-old takes it like it might explode. And that’s when Joseph understands. Everything he’s been told for 6 years is a lie. Quick pause, drop a comment, and let me know where you’re watching from.

What city? What state? What country? And what time is it where you are? Always cool to see how global this audience is. All right, let’s dive into how this happened. To understand why Joseph expected the worst, you have to understand the propaganda machine that shaped his reality for 6 years. And you have to understand what actually happened when German soldiers retreated through Austria in those final weeks of the war. Joseph Gerbles wasn’t an idiot. He was evil, yes, but not stupid.

As Reich Minister of Propaganda, he understood something fundamental about human psychology. Fear is a control mechanism. By spring 1945, Germany had lost the war. Everyone knew it. The question was how to keep the population from surrendering, from welcoming the Allies, from actively helping them. The answer, make them more afraid of the Allies than they were of continuing to fight. The propaganda campaign intensified dramatically after January 1945.

Radio broadcasts warned German and Austrian civilians that American soldiers were criminals released from prisons specifically to brutalize occupied populations. Newspapers ran fabricated stories about US troops gang- raping German women in captured towns. One widely distributed pamphlet claimed that American forces had orders to sterilize all German men between ages 15 and 50.

None of it was true, but repetition makes lies feel like truth. The campaign was particularly intense in Austria. The Nazi government couldn’t admit that Austria had welcomed the Anelless in 1938, that hundreds of thousands of Austrians had cheered Hitler’s arrival in Vienna. So, the propaganda had to walk a tight rope, convince Austrians they were loyal Germans who would be punished by the Allies while also preparing them for occupation.

Here’s what Joseph heard on the radio in April 1945, broadcast from Vienna. The American and British terror flyers have murdered thousands of German women and children in their beds. These are not soldiers. They are gangsters in uniform. When they occupy German soil, they will show no mercy. Protect your families. Hide your women.

Resist until death. The broadcasts included supposed eyewitness accounts. A woman from Aken, identified only as Frame M, described American soldiers storming through her town, looting homes, assaulting women. The account was vivid, detailed, specific. It was also completely fabricated. No Frame M existed. But Yseph had no way to know that. The visual propaganda was even more aggressive.

Posters showed American soldiers depicted as apes or demons. One poster featured a stars and stripes flag dripping with blood. Another showed a bombed out German city with the caption, “This is American culture.” By May 1945, Joseph had been marinating in this messaging for years.

He believed it because he had no alternative information, no internet, no independent media, just the official story repeated daily. But here’s the bitter irony. While Gerbles was warning Austrians about American brutality, the Vermacht was actually brutalizing them as it retreated. The German army that passed through Salfeldon in early May wasn’t the disciplined force of 1939. These were remnants, exhausted, demoralized, running from both the Americans and the Soviets.

They were also desperate and desperate soldiers take what they need. Vermachked units retreating through Austria in April and May 1945 confiscated food from farms without payment. They commandeered horses, carts, vehicles. In some villages, German military police executed deserters in public squares as warnings. The message to Austrian civilians was clear. We’re still in charge and will shoot anyone who helps the enemy…..

To be continued in C0mments ![]()

“You’re Not Stealing from Us?” — Austrian Farmer Meets Occupying American Troops…

It’s May 7th, 1945. A farming family in the small Austrian village of Salfeldon, about 50 mi south of Saltsburg, huddles in their cellar. Upstairs, they can hear engines, American engines. The father, we’ll call him Ysef, a name common enough in rural Austria, grips his wife’s hand. Their two daughters, ages 8 and 12, are crying quietly.

Joseph’s mother, 67 years old, prayed the rosary in the corner. For 6 years, Joseph has heard the same message from every newspaper, every radio broadcast, every party official who passed through town. The Americans are coming, and when they arrive, they will destroy everything.

They’ll burn farms, rape women, execute civilians, loot everything that isn’t nailed down. The folks storm, the desperate lastditch German militia has already retreated through the village two days ago, blowing the bridge over the Salak River as they left. The Americans are maybe 200 yards away now. Joseph made a decision yesterday.

He buried the family’s valuables, his wife’s jewelry, what little money they had saved, the silver candlesticks from his grandmother in a wooden box under the chicken coupe. He slaughtered their last pig and hid the meat in the root cellar covered with hay. If the Americans are going to take everything, he reasoned, at least they won’t find it all.

What Ysef doesn’t know, what 6 years of Ysef Gerbal’s propaganda machine has made impossible for him to know, is that the American soldiers rolling into his village right now are more likely to give his daughters chocolate than harm them. that the US Army has strict rules of engagement regarding civilian property, that American military police will actually arrest GIs who loot, that within 48 hours, American medics will be treating Austrian civilians for free in a field hospital setup in the village square. This is the story of what happened when Nazi propaganda met

American reality. And it starts with one simple question that Joseph will ask a US Army sergeant in about 20 minutes. A question so stunned, so genuinely confused that the sergeant will remember it for the rest of his life. Let’s back up 6 months. By November 1944, the Third Reich is collapsing.

The Red Army is smashing through Poland toward Germany’s eastern border. The Western Allies have liberated France and are pushing toward the Rine. for Austrian civilians and Austria has been part of Hitler’s Germany since the Anelus in 1938. The question isn’t whether Germany will lose. The question is who will occupy them when it’s over. Gerbles understands the fear factor perfectly.

His propaganda ministry has been preparing the German and Austrian population for this moment since 1943. The message is simple and repeated constantly. The Americans and British are bad. The Soviets are worse. But all of them will brutalize you if given the chance. The propaganda isn’t subtle. German newspapers print stories completely fabricated about American soldiers executing German prisoners.

Radio broadcasts describe American bombing raids as terror attacks designed to kill civilians. Posters show American soldiers as savage beasts. One poster distributed widely in Austria in early 1945 shows a learing American GI with a knife standing over a cowering German family.

The caption reads, “This is what awaits you.” For civilians in Western Austria, there’s a calculation happening. The Red Army is advancing from the east. The Americans are coming from the west. The Soviets have a reputation, a deserved one, for extreme brutality.

German refugees fleeing westward from Prussia and Sisia bring stories of Soviet atrocities, mass rape, summary executions, entire villages wiped out. So, here’s the twisted logic. Maybe the Americans will be slightly less terrible than the Soviets, but they’ll still be terrible. This is what Joseph believes as he sits in his cellar on May 7th, 1945. The engines stop. Joseph hears boots on the ground. Heavy boots. American boots.

His wife squeezes his hand so hard it hurts. The 12-year-old daughter has stopped crying and is just staring at the cellar ceiling, listening. Then, a knock on the door. Not a bang, not a boot kicking it in. A knock. A voice speaking German with a thick American accent. Hello? Anyone home? We’re American Army.

We’re not going to hurt you. Ysef freezes. This isn’t what he expected. Gerbles told him the Americans would smash down the door. They’d storm in with guns. They’d drag his family out. And another knock. Sir, ma’am, we know you’re in there. It’s safe to come out. Joseph looks at his wife. She’s shaking her head. Don’t go up there.

It’s a trick. The 67year-old grandmother has stopped praying and is staring at him. Joseph makes a decision. He stands up, his legs unsteady. He climbs the cellar stairs. His hand is on the door handle. He can hear men talking outside in English. He doesn’t speak English. For all he knows, they’re discussing how to break in. He opens the door.

Standing on his porch are four American soldiers. They’re not pointing guns at him. One of them, a sergeant, based on the stripes on his sleeve, is holding a pack of cigarettes. Another has a chocolate bar in his hand. They look tired, dirty, but not savage, not brutal. They look like guys who’ve been walking for weeks and just want to sit down.

The sergeant in his broken German says, “Good morning, sir. We need to search your house. Check for German soldiers. You understand?” Joseph nods. Can’t speak. The words won’t come. The Americans walk past him respectfully, not shoving, and begin searching the house. They’re not smashing furniture. They’re not grabbing things.

They’re just looking, opening doors, checking rooms. One of them finds the seller entrance and calls down in German. It’s okay. Come up. You’re safe. Joseph’s wife and daughters emerge. The grandmother follows. They’re all staring at these American soldiers like they’re aliens from another planet. The search takes 5 minutes. No German soldiers hiding, no weapons.

The sergeant nods to Joseph. Thank you for cooperating. Do you need anything? Food, medical supplies. Joseph just stares at him. Then he asks the question. The question that will haunt him, that will make him realize just how thoroughly Gerbles lied to him. You’re not stealing from us? The sergeant laughs, not cruy, just surprised. No, sir. We’re not stealing from you.

One of the other soldiers, the one with the chocolate bar, walks over to Joseph’s daughters and hands it to them. For the kids, he says in English, the 8-year-old takes it like it might explode. And that’s when Joseph understands. Everything he’s been told for 6 years is a lie. Quick pause, drop a comment, and let me know where you’re watching from.

What city? What state? What country? And what time is it where you are? Always cool to see how global this audience is. All right, let’s dive into how this happened. To understand why Joseph expected the worst, you have to understand the propaganda machine that shaped his reality for 6 years. And you have to understand what actually happened when German soldiers retreated through Austria in those final weeks of the war. Joseph Gerbles wasn’t an idiot. He was evil, yes, but not stupid.

As Reich Minister of Propaganda, he understood something fundamental about human psychology. Fear is a control mechanism. By spring 1945, Germany had lost the war. Everyone knew it. The question was how to keep the population from surrendering, from welcoming the Allies, from actively helping them. The answer, make them more afraid of the Allies than they were of continuing to fight. The propaganda campaign intensified dramatically after January 1945.

Radio broadcasts warned German and Austrian civilians that American soldiers were criminals released from prisons specifically to brutalize occupied populations. Newspapers ran fabricated stories about US troops gang- raping German women in captured towns. One widely distributed pamphlet claimed that American forces had orders to sterilize all German men between ages 15 and 50.

None of it was true, but repetition makes lies feel like truth. The campaign was particularly intense in Austria. The Nazi government couldn’t admit that Austria had welcomed the Anelless in 1938, that hundreds of thousands of Austrians had cheered Hitler’s arrival in Vienna. So, the propaganda had to walk a tight rope, convince Austrians they were loyal Germans who would be punished by the Allies while also preparing them for occupation.

Here’s what Joseph heard on the radio in April 1945, broadcast from Vienna. The American and British terror flyers have murdered thousands of German women and children in their beds. These are not soldiers. They are gangsters in uniform. When they occupy German soil, they will show no mercy. Protect your families. Hide your women.

Resist until death. The broadcasts included supposed eyewitness accounts. A woman from Aken, identified only as Frame M, described American soldiers storming through her town, looting homes, assaulting women. The account was vivid, detailed, specific. It was also completely fabricated. No Frame M existed. But Yseph had no way to know that. The visual propaganda was even more aggressive.

Posters showed American soldiers depicted as apes or demons. One poster featured a stars and stripes flag dripping with blood. Another showed a bombed out German city with the caption, “This is American culture.” By May 1945, Joseph had been marinating in this messaging for years.

He believed it because he had no alternative information, no internet, no independent media, just the official story repeated daily. But here’s the bitter irony. While Gerbles was warning Austrians about American brutality, the Vermacht was actually brutalizing them as it retreated. The German army that passed through Salfeldon in early May wasn’t the disciplined force of 1939. These were remnants, exhausted, demoralized, running from both the Americans and the Soviets.

They were also desperate and desperate soldiers take what they need. Vermachked units retreating through Austria in April and May 1945 confiscated food from farms without payment. They commandeered horses, carts, vehicles. In some villages, German military police executed deserters in public squares as warnings. The message to Austrian civilians was clear. We’re still in charge and will shoot anyone who helps the enemy.

Ysef’s village had a visit from the Vermacht on May 5th, 2 days before the Americans arrived. A Vafan SS unit, maybe 40 men, came through heading east. They took six of Joseph’s chickens, two bags of flour, and a cart. No payment, no receipt, just took them. When Joseph’s neighbor protested, a sergeant told him to shut up or he’d be arrested for defeatism.

So, here’s Joseph’s reality on May 7th. The German forces he’s supposed to be loyal to just stole his property, and the American forces he’s been told are monsters are about to arrive. He expects the Americans to be worse because Gerbles has spent 6 years telling him they will be. The Eastern Front adds another layer of terror.

By May 1945, everyone in Austria has heard stories about the Red Army. These stories, unlike the fabrications about the Americans, are largely true. Soviet forces advancing through eastern Austria in April 1945 engaged in systematic mass rape. The numbers are horrifying. Historians estimate between 70,000 and 100,000 Austrian women were raped by Soviet soldiers during the occupation.

Soviet troops looted systematically. Summary executions of suspected Nazis or just random German-speaking men were common. This created a perverse comparison in Austrian minds. The Soviets are definitely terrible. The Americans are probably terrible. Therefore, we’re doomed either way.

Refugees fleeing westward from Vienna brought firsthand accounts. Soviet soldiers entering homes and assaulting women while other soldiers stood guard. farms stripped completely bare. Men shot for wearing anything that looked like a military uniform, even old vermached jackets civilians wore because they had no other coats. The contrast would become stark over the next few weeks.

But Ysef doesn’t know that yet. All he knows is that Austria is being carved up between powers that, according to everything he’s been told, will destroy everything he has. There’s another factor, guilt. Austria’s relationship with Nazism is complicated. The Anelus in 1938 wasn’t exactly forced on Austria. Hundreds of thousands of Austrians enthusiastically supported it.

Austrian soldiers served in the Vermacht. Austrian citizens participated in the Holocaust. Mountousen concentration camp, one of the worst in the Nazi system, was on Austrian soil. By May 1945, many Austrians are starting to understand they’re going to be held accountable. The Allies aren’t going to distinguish between German Germans and Austrian Germans. They collaborated.

They participated. Now comes the reckoning. This adds another layer to Ysef’s fear. It’s not just that the Americans might be brutal conquerors. It’s that they might be justified. Maybe this is punishment. Maybe Gerbles was wrong about American methods, but right about American intentions.

Ysef doesn’t consider himself a Nazi. He never joined the party. He didn’t attend rallies. He just farmed his land and tried to stay out of politics. But he knows that won’t matter to an occupying army. He’s German speakaking. He lived under Nazi rule for seven years. That makes him complicit. So when those four American soldiers walk into his house on May 7th, Joseph expects the worst.

He expects them to see him as the enemy. He expects them to take everything. He expects violence. What he doesn’t expect, what 6 years of propaganda never prepared him for, is the US Army’s actual occupation policy. And that policy is about to shatter everything he thought he knew.

The policy that governed how those four American soldiers behaved in Joseph’s house on May 7th, 1945 didn’t materialize out of thin air. It was the result of two years of planning by the US War Department informed by painful lessons from World War I and shaped by a fundamental calculation. Winning the peace matters as much as winning the war. General Dwight D. Eisenhower issued the occupation directive for Austria in March 1945, 2 months before American troops crossed the border.

The document designated JCS 1067 for Germany and adapted for Austria was specific about civilian treatment. Section 4, paragraph 3 stated, “Fratonization with German civilians will be discouraged. However, military necessity and common decency will govern all interactions. Looting is strictly prohibited and will be prosecuted under the articles of war.

Translation: Don’t be buddies with the locals, but don’t be animals either. The directive continued with specifics. American soldiers could not confiscate civilian property without official requisition and compensation. They could not enter homes without military necessity.

Searching for German soldiers, weapons, or Nazi officials qualified. Stealing food did not. Sexual assault would be prosecuted as a capital offense. Unauthorized requisition of civilian vehicles, livestock, or supplies would result in court marshal. This wasn’t just paperwork. The US Army meant it, and enforcement started immediately.

On May 8th, 1945, one day after Joseph’s encounter, a private in the Third Infantry Division was arrested in the town of Bad Reichenhal, 15 miles from Salfeldon, for stealing a watch from an Austrian civilian. He was court marshaled within a week. Sentenced to 6 months in military prison and forfeite of pay, the message spread fast through American units.

The rules apply, and breaking them has consequences. But enforcement alone doesn’t explain what happened in Joseph’s house. It doesn’t explain why that sergeant spoke to him respectfully, why the soldier gave his daughters chocolate, why they searched his property without destroying it.

For that, you have to understand who these American soldiers actually were. The average American GI in Europe in May 1945 was 26 years old. He’d been drafted or enlisted between 1942 and 1944. Before the war, he’d been a factory worker, a farmer, a shop clerk, a college student. The Third Infantry Division, which occupied Salfeldon, included guys from Ohio, Texas, California, New York.

They’d fought through North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Southern France, and into Germany. They’d seen combat. They’d lost friends. They were also exhausted. By May 1945, the average infantry soldier in Europe had been in the field for 18 to 24 months. They’d been shot at, shelled, bombed. They wanted to go home.

They did not want to occupy hostile territory any longer than necessary. Here’s the calculation that shaped their behavior. Treating civilians decently made occupation easier. Happy civilians, or at least non-hostile civilians, don’t snipe at you. They don’t sabotage supply lines. They don’t hide German soldiers. They tell you where the weapons caches are.

Brutality might satisfy revenge urges in the short term, but it creates insurgencies in the long term. The US Army had learned this lesson the hard way in the Philippines between 1899 and 1902. American forces fighting Filipino insurgents after the SpanishAmerican War used brutal tactics, torture, village burning, civilian massacres.

It worked in the short term. It created a legacy of resentment that lasted decades. Army leadership in 1945 remembered. But there’s another factor, less cynical and more human. Most American soldiers didn’t want to terrorize civilians. They weren’t sociopaths. They were guys who wanted to finish the job and go home to their families.

Beating up Austrian farmers didn’t accomplish that. The sergeant who spoke to Joseph, let’s call him Sergeant Miller, a composite of actual veterans accounts, was from Michigan. He’d worked in an auto plant before the war. He’d been in Europe since Anio in January 1944. He’d seen terrible things and done things he didn’t want to remember.

But he’d also seen what happened when armies brutalized civilians. In Italy, he’d watched German troops burn villages in reprisal operations. It didn’t stop Italian partisans. It made them angrier and more determined. So when Miller walked into Joseph’s house, he wasn’t thinking about propaganda or policy. He was thinking, “Let’s search this place, make sure there are no holdouts, and move on. The civilian family is scared.

Make it quick. Don’t make it worse. The chocolate bar wasn’t official policy. That was Private Rodriguez from Texas who’d picked up a box of Hershey bars at a supply depot 3 days earlier. He had kids back home. Two daughters, ages seven and nine. When he saw Joseph’s daughters crying in the cellar, he saw his own kids.

The chocolate bar was impulse, just trying to make scared children less scared. This is the machinery behind Yseph’s shock. Gerbles had prepared him for monsters. He got Miller and Rodriguez instead. The contrast with Soviet occupation policy in eastern Austria was immediate and stark. The Red Army operated under different assumptions.

Soviet soldiers had spent four years fighting across territory where German forces had deliberately starved millions, raised villages, and exterminated populations. They’d seen Lennengrad, Stalenrad, the destroyed cities of Ukraine and Bellarus. They arrived in Austria with a very specific mindset. Germany started this war and Germans would pay for it.

Soviet commanders, unlike American ones, often looked the other way when their troops looted or assaulted civilians. Stalin’s attitude expressed to Yugoslav communist Milivangelis in April 1945 was blunt. Can’t you understand it if a soldier who has crossed thousands of kilometers through blood and fire and death has fun with a woman or takes some trifle? The result in Soviet occupied eastern Austria the behavior Gerbles had predicted actually happened. Women were raped. Property was looted.

Men were arrested and deported to Soviet labor camps on flimsy charges. The contrast between Americanoccupied Western Austria and Soviet occupied Eastern Austria was so extreme that it defied explanation through propaganda alone. Joseph learned about this within weeks. His cousin lived in St.

Pilton, 60 mi west of Vienna in the Soviet zone. Letters arrived, smuggled through by refugees, describing the chaos. Soviet soldiers stripping farms completely, mass rapes, arbitrary arrests. The Austrian Communist Party trying to establish control with Soviet backing. Meanwhile, in Salfeldon, the Americans set up a field hospital on May 10th.

Austrian civilians could receive free medical treatment. Medics treated everything from combat wounds to childhood diseases to farming injuries. No charge, no political screening, just medicine. On May 12th, American military government officers arrived with interpreters. They announced food distribution. The US Army would provide flour, canned goods, and powdered milk to prevent starvation.

Not as charity, as calculated policy. Starving people revolt. Fed people cooperate. Joseph went to the first distribution. He received 50 pounds of flour, 12 cans of spam, and powdered milk. He had to sign a receipt. The American lieutenant running the operation through an interpreter explained, “This is not payment. This is not charity.

This is to help you until your economy restarts. We need Austria stable.” Joseph walked home carrying American supplies, his head spinning. 5 days ago, he’d buried his valuables, expecting Americans to steal everything. Now, Americans were giving him food. The cognitive dissonance was overwhelming.

6 years of propaganda versus 5 days of reality. The propaganda lost. The moment when Joseph’s entire world view collapsed didn’t come with the chocolate bar or the food distribution. It came on May 18th, 1945, 11 days after the Americans arrived when two military police officers knocked on his door and asked if he’d file a complaint.

A US Army private had been seen taking eggs from Joseph’s chicken coupe without permission. A neighbor had reported it. The MPs wanted to know, did Joseph want to press charges? Joseph stared at them. Press charges against an American soldier for eggs. How many eggs? The MP sergeant asked through an interpreter. Six, Yseph said. Maybe seven.

Do you want to file an official complaint? The soldier will face military justice if you do. Ysef shook his head. Not because he was afraid, because the entire situation was insane. The Vermacht had taken his chickens, his flower, his cart. No questions, no compensation, no apology.

Now the American army was offering to prosecute one of their own soldiers for seven eggs. It’s okay, Joseph managed. He can have the eggs. The MP sergeant nodded. Understood. But just so you know, that soldier is going to get an ass chewing from his co whether you file or not. Taking civilian property without authorization violates orders. This was the machinery of American occupation policy in action. And it was working.

By late May 1945, American forces occupied all of Western Austria, Salsburg, Tiroll, Vorlberg, and parts of Upper Austria. That’s roughly 32,000 square miles and about 2.2 million civilians. The occupation force consisted of elements from the US Third Army and 7th Army totaling approximately 150,000 troops at peak strength. The challenge was immediate. How do you control 2.

2 million people, many of whom had supported the Nazi regime, without massive repression or violence? The American approach had three components. First, enforce strict discipline on US troops to prevent abuse. Second, establish functional civil administration quickly to prevent chaos. Third, separate actual Nazis from regular civilians through a screening process.

The discipline piece was working. Between May 8th and June 30th, 1945, the US Army court marshaled 127 soldiers in the Austrian occupation zone for crimes against civilians. The charges ranged from theft to assault to rape. 38 received prison sentences. Four received death sentences for rape and murder, though two were later commuted.

Compare that to the Soviet zone. Soviet military tribunals in eastern Austria during the same period prosecuted approximately zero Soviet soldiers for crimes against Austrian civilians. Not because crimes weren’t happening. They were extensively, but because Soviet command policy didn’t prioritize it.

The administrative peace took longer but moved fast by occupation standards. American military government detachments, small units of officers and enlisted men trained in civil administration, fanned out across Western Austria. Their job, restore basic services, establish local government, get the economy moving.

In Salfeldon, a six-man military government team arrived on May 15th. Captain John Sawyer, a lawyer from Pennsylvania in civilian life, was in charge. His team included a German-speaking sergeant, a logistics specialist, a medical officer, an engineer, and a clerk. Their first task, appoint a local mayor.

The previous mayor was a Nazi party member currently in detention. Sawyer’s team interviewed candidates, ran background checks, consulted with locals. They appointed France Huber, a 54year-old shopkeeper who’d never joined the Nazi party and had a reputation for fairness. Hooer took office on May 20th. This was happening across Western Austria. American military government appointed interim local officials, usually Austrians, with no Nazi connections.

The officials had authority over local police, sanitation, food distribution, and schools. American officers supervised but didn’t micromanage. The goal wasn’t to Americanize Austria. The goal was to establish stable non-Nazi governance quickly. The denazification screening process was more complicated.

In theory, every Austrian adult had to complete a frogen, a 131 question form about their activities during the Nazi period. Were you a party member? Did you hold party office? Did you participate in persecution of Jews or political opponents? Did you profit from Aryanization of Jewish property? The forms were processed by military government teams.

Based on the answers, Austrians were classified into categories: major offenders, offenders, lesser offenders, followers, and exonerated. The classifications determined whether you could vote, hold office, own a business, or work in certain professions. In practice, the system was overwhelmed immediately. In Salsburg province alone, military government teams had to process approximately 180,000 frogen forms.

They had maybe 40 officers and 100 enlisted personnel to do it. The math didn’t work. So the Americans made a practical decision. Focus on the big fish. Arrest SS members, senior Nazi officials, concentration camp guards, and Gestapo officers. Process them first. The small-time party members, guys who joined to keep their jobs or because everyone in town was joining, got lower priority.

Ysef filled out his Frogabogen on May 25th. The questions were invasive. Had he joined the Nazi party? No. Had he attended rallies once in 1938 because the whole village was required to attend? Had he donated money to Nazi organizations? Yes. The Winter Relief Fund because refusing would have made him a target. Had he employed forced laborers? No.

The American sergeant reviewing his form spent maybe 3 minutes on it, stamped it. Category 5 exonerated. Joseph could vote in future elections, own property, work freely, no restrictions. The sergeant handed back the form. You’re clear. Don’t cause trouble. That was it. No punishment, no interrogation. The Nazi period was over and Ysef could move on with his life.

But not everyone got off that easy. In Zfeldon, the Americans arrested 14 men in the first month of occupation. Eight were SS members. Four were local Nazi party officials. Two were accused of specific crimes. One for beating a prisoner of war, another for confiscating Jewish property. They were held in a detention center in Salsburg, awaiting trial.

Some would be convicted, some would be released. But the process was systematic, not arbitrary. There were charges. There was evidence. There were lawyers, however rudimentary. Joseph watched this unfold with a mix of relief and confusion. Relief because he wasn’t targeted. Confusion because the occupiers were acting like a government, not a conquering army.

The economic situation stabilized faster than anyone expected. By June, American military government had restarted the railway system in western Austria. Trains ran between Salsburg, Insbrook and local villages. Food distribution became regular. Markets reopened. The Americans brought in supplies from Germany, captured Vermached stores, US Army surplus, requisitioned goods.

They established official exchange rates for the Reichsmark and began transitioning to a new Austrian currency. They rebuilt bridges the Vermacht had destroyed during retreat. In Salfeldon, American engineers repaired the bridge over the Salak River by June 10th. It took 3 weeks.

They used local Austrian labor paid in food and cigarettes because currency was unstable. The workers were supervised by US Army engineers who treated them like construction workers, not slave labor. Joseph got a job on the bridge crew. He carried lumber, mixed concrete, held tools. An American corporal from Nebraska taught him the English words for hammer, nail, board.

They didn’t have long conversations, language barrier, but they worked together. The corporal shared his lunch one day. spam sandwich and an apple. Ysef reciprocated with bread his wife had baked. This was occupation, not oppression, not liberation exactly, but not the nightmare Gobles had promised.

By the end of June 1945, Western Austria under American occupation had functioning local government, restored infrastructure, regular food supply, and a screening process for denazification. The contrast with the Soviet zone in eastern Austria was impossible to ignore. Refugees continued fleeing westward.

By July, an estimated 40,000 Austrians had crossed from the Soviet zone into American occupied territory. They brought stories that confirmed every fear Joseph had about occupation. Except the occupiers in those stories were Soviets, not Americans. The Americans faced a dilemma. Accept the refugees and strain resources or turn them back to Soviet control. They chose acceptance, establishing refugee camps and processing centers.

It strained supplies but avoided the moral catastrophe of forcing people back into brutality. Ysef volunteered at a refugee processing center in Salsburg in July. He heard firsthand accounts from people who’d experienced both occupations. A woman from Viner Noat described Soviet soldiers looting her family’s apartment at gunpoint.

A man from Grods described being arrested by Soviet NKVD officers held for 2 weeks without charges, released when they decided he wasn’t important enough to deport. Every story reinforced the same conclusion. The Americans weren’t perfect, but they were trying to be decent. The Soviets weren’t trying.

The question Joseph asked on May 7th, “You’re not stealing from us?” became a punchline among American soldiers in Austria. Sergeant Miller told the story to his platoon. They told it to other units. By June 1945, variations of the story circulated through the occupation force. The shocked Austrian farmer became shorthand for how completely Nazi propaganda had failed.

But the question represented something deeper than one man’s surprise. It represented the collapse of Gerbal’s entire narrative framework. And that collapse had consequences that shaped the next 50 years. By August 1945, 3 months into occupation, Western Austria under American control had stabilized to a degree that surprised everyone, including the Americans themselves.

Crime rates were lower than they’d been under Nazi administration. Black market activity existed, but was manageable. Food supplies, while limited, were adequate. Most importantly, there was no insurgency. This last point deserves emphasis. The Nazi regime had spent its final months preparing for Werewolf, a guerilla resistance movement that would harass occupation forces after Germany’s defeat. Weapons were cashed.

Underground cells were organized. Young men were trained for sabotage and assassination. In Western Austria, Vervolf never materialized. There were isolated incidents. A sniper shot at American troops in Innbrook in June. Two military government officers were attacked in a village near Bragens. But nothing systematic. No organized resistance, no sustained campaign.

Why? Because resistance requires popular support and the Austrian population in the American zone had no interest in supporting it. The Americans weren’t behaving like brutal occupiers. So there was no motivation to resist brutally. The propaganda had promised one thing. Reality delivered another. The disconnect was too extreme.

The contrast with the Soviet zone remained stark through 1945 and beyond. In eastern Austria, Soviet occupation forces faced persistent resistance. Partisan groups, initially targeting Soviet troops, operated in rural areas through 1946. The Soviets responded with mass arrests and deportations. By late 1945, approximately 15,000 Austrians from the Soviet zone had been deported to labor camps in the USSR.

Most were accused of being Nazis or Nazi collaborators. Many were simply men of military age the Soviets wanted for labor. This created a feedback loop. Soviet brutality generated resistance. Resistance justified more Soviet brutality.

By 1946, the Soviet zone was economically devastated and politically unstable. The American zone went the opposite direction. By early 1946, Western Austria had functioning democratic local government. recovering infrastructure and growing economic activity. Schools reopened. Universities resumed classes. Cultural institutions, theaters, orchestras, museums started operating again.

The Americans made mistakes. Denazification screening was inconsistent and sometimes arbitrary. Some actual Nazis slipped through by lying on their frogen forms. Some small-time party members received harsh treatment while more significant figures escaped. The process wasn’t perfect, but the overall trajectory was clear.

American occupation policy in Austria worked, and it worked because of decisions made before the first soldier crossed the border. Decisions about how to treat civilians, how to enforce discipline, how to balance security with legitimacy. Ysef’s village of Salfeldon recovered faster than he’d expected. By spring 1946, farming had returned to near normal productivity.

The Americans requisitioned some produce for occupation forces, but paid in the new Austrian shilling currency. The bridge was rebuilt. The railway ran regularly. Life wasn’t comfortable, but it was livable. Joseph never forgot that moment on May 7th, 1945. He told the story to his daughters when they were older. He told it to his grandchildren.

The shock of that sergeant’s answer, “No, sir, we’re not stealing from you,” remained vivid decades later. But the story’s significance extended far beyond one Austrian farmer’s surprise. It became part of a larger narrative that shaped post-war Europe. The American occupation of Austria and Germany demonstrated that democratic reconstruction was possible.

It proved that former enemies could be transformed into stable allies through consistent policy and decent treatment. This wasn’t guaranteed. It required planning, discipline, resources, and political will. But it worked. The contrast between American and Soviet occupation zones became a defining feature of the Cold War.

West Germany under American, British, and French occupation became a prosperous democracy. East Germany under Soviet occupation became a police state. Austria split between Western and Soviet zones from 1945 to 1955 experienced the same divergence.

The Marshall Plan, announced by Secretary of State George Marshall in June 1947, grew directly from lessons learned in Austria and Germany. The plan provided massive economic aid to rebuild Western Europe, $13 billion between 1948 and 1951, equivalent to roughly $150 billion today. Austria received approximately $962 million in Marshall Plan aid. The aid wasn’t charity.

It was calculated strategy. Stable, prosperous economies don’t turn communist. They don’t generate refugees. They become trading partners and military allies. The investment paid off. Austria regained full sovereignty in 1955 with the Austrian state treaty. The Soviets withdrew from Eastern Austria. The Americans, British, and French withdrew from Western Austria.

Austria committed to permanent neutrality. No joining NATO or the Warsaw Pact as the price for Soviet withdrawal. But the 10 years of occupation had set trajectories that neutrality couldn’t erase. Western Austria had been integrated into Western economic systems. Eastern Austria had been drained by Soviet exploitation.

When the occupiers left, Austria oriented westward economically and culturally, even while remaining officially neutral politically. The military lessons were significant, too. The US Army’s experience in Austria informed occupation policy in Japan, Korea, and later conflicts. The principle that disciplined troops treating civilians decently produces better outcomes than brutality became doctrine.

Not always followed, Vietnam demonstrated that, but established as the standard. Joseph lived until 1987. He saw Austria transform from a devastated occupied territory to a prosperous neutral state. He saw his daughters grow up in a democratic society. He saw his village grow from 2,500 people to over 15,000 driven by tourism and economic development. He never became particularly pro-American.

He wasn’t anti-American either. He just recognized that the Americans had treated him fairly when they didn’t have to. That Sergeant Miller could have stolen his chickens and vegetables and faced no consequences. That Private Rodriguez could have ignored his crying daughters.

That the MPs could have laughed at him when he reported stolen eggs. They didn’t. And that made all the difference. The propaganda Gerbles built was sophisticated, pervasive, and ultimately brittle. It worked as long as Germans and Austrians had no alternative information, but it couldn’t survive contact with reality. When Joseph met actual American soldiers and they didn’t match the propaganda’s description, the entire narrative collapsed.

This is the lesson that echoes beyond 1945. Propaganda that’s completely divorced from reality is vulnerable. It can shape perceptions up until the moment people experience the truth for themselves. Then it shatters. Gerbles killed himself on May 1st, 1945, 6 days before American troops reached Zalfeldon.

He never knew how thoroughly his final propaganda campaign would fail. He never heard about Ysef’s question. He never saw Austrian civilians welcoming American occupation as relief rather than resisting it as oppression. The ultimate irony. Goal’s propaganda about American brutality probably made the occupation easier. By setting expectations impossibly low, he guaranteed that anything short of atrocity would feel like mercy.

The Americans didn’t have to be saints. They just had to be decent. And decent was enough. Joseph’s question, “You’re not stealing from us?” echoes across 80 years because it captures a moment when propaganda met reality and lost. When fear built on lies collapsed under the weight of evidence, when occupied, people discovered their occupiers were human beings trying to do a difficult job as honorably as possible.

That doesn’t make the Americans heroes. It makes them soldiers following orders designed to produce stable occupation rather than perpetual conflict. But in May 1945, in a small Austrian village, that was enough to shock a farmer who’d been prepared for the worst and received something fundamentally different.

The chocolate bar Private Rodriguez gave to Joseph’s daughters. One of them kept the wrapper for years. It’s probably in a drawer somewhere in Austria.

News

CH2 . The Japanese couldn’t believe a P-61 was hunting them — until four bombers disappeared in 80 minutes… At 2340 on December 29th, 1944, Major Carol C. Smith crouched in the cramped cockpit of his P61 Black Widow at Meuire Field, Muro, watching his radar operator track a contact moving at 180 knots through the black skies north of the Philippine Islands. 26 years old, 43 combat missions, four confirmed kills.

The Japanese couldn’t believe a P-61 was hunting them — until four bombers disappeared in 80 minutes…At 2340 on December…

CH2 . May 8th, 1945. The day the war officially ended. 10-year-old Helmet Schneider pressed his face against the cold cellar wall, listening to the rumble of American tanks rolling through his street. His mother’s hand gripped his shoulder so tightly it hurt, but he did not complain.

May 8th, 1945. The day the war officially ended. 10-year-old Helmet Schneider pressed his face against the cold cellar wall,…

CH2 . Lieutenant Junior Grade Kau Hagawa gripped the control stick of his P1Y Francis bomber as anti-aircraft fire exploded around his aircraft. Through the canopy, he could see the American task force spread across the ocean below battleships, cruisers, destroyers. Somewhere down there was his target, the cruiser USS San Francisco. This was Hagawa’s moment.

Japanese Kamikaze Pilot Thought He’d Be Executed — But the Americans Saved Him Instead.. Lieutenant Junior Grade Kau Hagawa gripped…

CH2 . Lieutenant Cara Mitchell stood at the edge of the training grounds at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, watching the morning fog roll in from the Pacific. The salt air clung to her skin as she mentally prepared for the day ahead. At 5’4 and 130 lbs, she knew what the SEALs would see when she walked into that training hall.

Lieutenant Cara Mitchell stood at the edge of the training grounds at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, watching the morning fog…

CH2 . Camp Florence, Arizona. July 1944. The 4th of July celebration smelled of charcoal and frying onions. And Sergeant Maria Kaufman watched the American guards set up a strange assembly lying metal grills, split bread rolls, pink sausages that looked nothing like German worst.

Camp Florence, Arizona. July 1944. The 4th of July celebration smelled of charcoal and frying onions. And Sergeant Maria Kaufman…

CH2 . Starving German POWs Couldn’t Believe What Americans Served Them for Breakfast… May 17th, 1943, Northern England. Cold mist hung low over the railard, wrapping the countryside in a damp, gray silence. The cattle cars hissed as steam curled from beneath their iron wheels. Inside, 180 German soldiers waited, cramped and sleepless after 3 days of transport from the ports of Liverpool.

Starving German POWs Couldn’t Believe What Americans Served Them for Breakfast…May 17th, 1943, Northern England. Cold mist hung low over…

End of content

No more pages to load