WWII’s Fastest Fighter Aircraft — Which Plane Was the True King of Speed?

For nearly eighty years, one question has refused to die. It has echoed through aircraft hangars thick with the smell of oil and aluminum, whispered at airshows by veterans who still remember the sound of piston engines shaking their bones, and debated relentlessly in the dim halls of VFW posts where old pilots gather and memories outlive the men themselves. It is a question forged in steel, horsepower, and sheer human nerve—a question that seems simple, but is anything but simple.

What was the fastest propeller-driven fighter aircraft of the Second World War?

People argue about it with the same heat they once used to argue politics, because to pilots and engineers, speed was more than a number—it was survival, it was dominance, it was national pride, and it was the cutting edge of physics pushed to its absolute breaking point. Today, we are not dealing in hangar gossip or nostalgic bar-room legends. We are here to set the record straight. But to do that honestly, we must confront a truth: the word “fastest” is dangerously deceptive.

Because what does “fastest” actually mean?

Are we talking about speed at sea level, where the air is so thick it feels like flying through soup? Or speed at thirty thousand feet, where the air is thin, hostile, and frozen—exactly where bomber formations fought for their lives? Are we talking about a stripped, polished, factory-fresh test aircraft pushed to the limit under ideal conditions? Or the real machines pilots flew into battle—burdened with ammunition, guns, armor plates, and the crushing weight of knowing they might not come home?

The truth is that in WWII, speed was a weapon, but it was a specialized weapon. A fighter that could dominate at five thousand feet might be nearly useless at thirty-five thousand. An aircraft that dazzled engineers in test trials might gasp for breath in real combat. There was no single environment, no single altitude, no single definition that allowed one aircraft to stand unchallenged.

So to find out which machine truly sat on the throne of speed, we must turn to what the wartime pilots and engineers left behind: official test data, archived performance reports, and declassified documents written at a time when nations were desperate, and accuracy meant survival.

This is not a list. This is an investigation—an investigation into the most advanced piston-engine fighters ever built, the last, thunderous roar of the propeller age before jets rewrote the future of flight forever.

And there is only one place we can begin our search: the cold, brutal skies above thirty thousand feet. Because that was where the desperate need for speed became a matter of life and death.

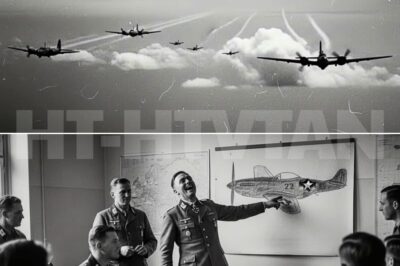

By 1944, the American Eighth Air Force was plunging deep into Germany again and again, and the Luftwaffe faced a crisis unlike anything it had confronting earlier in the war. Their two standard fighters—the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and the Focke-Wulf Fw 190—were extraordinary machines in a low-altitude brawl, deadly, agile, and flown by some of the most experienced aces the world had ever seen. But they carried a flaw that altitude made impossible to hide.

When these fighters climbed into the thin, freezing upper atmosphere, where American bombers and escorts operated, their engines suffocated. Performance collapsed. Maneuverability plummeted. Speed evaporated. They simply could not keep up.

That left the Luftwaffe facing a catastrophic vulnerability: they could no longer reliably intercept the high-flying B-17s and P-51s, and every failure meant more Allied bombs raining down on German factories, railroads, and cities already burning under relentless assault.

Germany desperately needed a new kind of predator—one built not for low-altitude combat, but for the cruel upper reaches of the atmosphere. They needed a Hochleistungsjäger, a high-performance fighter designed to hunt at heights where other aircraft gasped for air.

The man tasked with solving this crisis was Kurt Tank—one of the greatest aviation minds in history. His answer would produce one of the most fearsome piston-engine machines ever conceived: the Focke-Wulf Ta 152H.

This aircraft was not just a modified Fw 190. It was something entirely different, built with a singular purpose: to dominate the sky where oxygen was scarce, temperatures plunged, and engines failed if not engineered to perfection.

The proof was in the wings. One look told the whole story. They stretched outward with impossible length and slender grace, reaching nearly forty-eight feet tip to tip. These were not the wings of a dogfighter. They were the wings of a high-altitude predator, designed like a glider to cling to thin air, to generate lift where other fighters stalled and fell.

But a wing like that meant nothing without power—immense, relentless power. And so the Ta 152H was built around the Jumo 213E inline engine, one of the most advanced powerplants of the war. But calling it an engine understates its complexity. It was a breathing machine, a mechanical organism designed to survive where the atmosphere itself was trying to choke it into silence.

Its core was the two-stage, three-speed supercharger—a masterpiece of wartime engineering. This device forced compressed air into the engine at altitudes where normal engines starved. It allowed the aircraft to breathe, to generate horsepower where other fighters sputtered and failed. It also gave the pilot a temporary burst of power, enough to escape, to pursue, or to survive.

By the time it flew, this machine represented the absolute limit of piston-engine innovation, the razor’s edge of aeronautical engineering pushed as far as wartime resources could allow.

And so, to answer the question of the fastest WWII fighter, we must confront what machines like the Ta 152H truly achieved—machines built at a moment when desperation, technology, and human will collided at thirty thousand feet…

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

For nearly eighty years. A single question has echoed in workshops, at airshows, and in the quiet halls of V F W posts. It’s a question of steel, of horsepower, and of sheer, unadulterated nerve. What was the fastest propeller driven fighter aircraft of the Second World War? Today, we’re not dealing in hangar gossip or bar-room bets.

We are setting the record straight. But to do that, we have to agree on the rules. “Fastest” is a dangerously simple word for a very complicated problem. Are we talking about speed at sea level, where the air is thick as soup, or up at thirty thousand feet in the thin, frozen air where the bombers flew? Are we talking about a clean, stripped-down airframe in a test flight or a battle-hardened machine? Loaded with guns, ammunition and a pilot desperate to get home? The truth is, speed was a weapon.

And it was specialized. The fastest plane at five thousand feet might be a sitting duck at thirty-five thousand. So to find the true king of Speed, we must look at the official test data, the declassified wartime reports. And find the machine that pushed the laws of physics to their absolute breaking point. This isn’t just a list.

This is an investigation into the most advanced piston-engine aircraft that ever saw combat, or were built to see it. These are the thoroughbreds, the machines that represented the last glorious roar of the propeller before the jet age changed everything. We begin our search in the one place that drove the desperate need for speed more than any other.

The cold, hostile skies above thirty thousand feet. By nineteen forty-four, the American Eighth Air Force was punching deep into Germany, and the Luftwaffe had a terrible, existential problem. Their standard fighters, the Messerschmitt one-oh-nine and the Focke-Wulf one-ninety, were excellent brawlers. Down low, but up in the thin air their engines gasped.

Their performance fell off a cliff, leaving them vulnerable to the American escorts and struggling to intercept the high-flying B-seventeens. Germany needed a new kind of hunter. They needed a Hochleistungsjäger, a high-performance fighter. The answer came from one of the greatest aviation minds in history. Kurt Tank.

His solution was the Focke-Wulf T A one fifty-two H. This aircraft was a different animal entirely from the Butcher Bird it was based on. You can see it immediately in those wings. They are impossibly long and slender, stretching to nearly forty-eight feet. This was a glider’s wing, designed to grip the thin air molecules and provide lift where there was almost none.

But a wing like that needs power. Immense power. The T A one fifty-two H was built around the Jumo two-thirteen E inline engine. This wasn’t just a motor. It was a complex breathing apparatus. It used a two-stage, three-speed supercharger, a mechanical marvel that forced compressed air into the engine, allowing it to breathe at altitudes where others suffocated and to give it an extra burst.

It had the G M one boost system—injecting nitrous oxide or laughing gas directly into the engine. A shot of adrenaline that could briefly push it past its limits. The result at forty-one thousand feet with the boost in gauge, the T A one fifty-two H was documented at an astonishing four hundred seventy-two miles per hour for the Allied pilots in their P-fifty-ones and P-forty-sevens.

This was the phantom, a German fighter that could appear from above. Untouchable strike with a massive thirty-millimeter cannon firing through the propeller hub, and then use its superior climb rate to simply vanish back into the stratosphere. It even had a pressurized cockpit, a rarity that kept its pilot conscious and effective in the brutal cold.

But this incredible machine was a prime example of too little, too late. It was complicated to build, and by the time it entered service in January nineteen forty-five, Germany’s factories were rubble and its supply lines were shattered. Only about sixty-seven were ever built. They saw very little combat, but they left a mark.

One of the few aces to fly it, Oberfeldwebel Willi Reschke famously engaged a flight of Hawker Tempests. The Tempests were superb fighters, but Reschke, low on fuel and cornered, simply used his superior climb and altitude performance to escape. Later, he reportedly engaged four P-fifty-one Mustangs at high altitude, shooting down two before the others could even react.

It was a glimpse of what might have been a specialized king built for the thin air, and at those heights it was almost certainly the fastest prop plane in the sky. But the Americans had their own high-altitude problem. It wasn’t just the T A one fifty-two; it was the arrival of the M E two sixty-two jet. Suddenly even the superb P-fifty-one D was sluggish.

The Army Air Forces needed a jet-killer. Their answer was the Republic P-forty-seven M Thunderbolt. Now we all know the P-forty-seven, the Jug, a seven-ton monster that could soak up damage that would shred any other fighter and still bring its pilot home. It was tough, but it was heavy to turn this beast into a high-altitude interceptor.

The engineers at Republic had to turn it into a hot rod. They took the massive Pratt & Whitney R-twenty-eight hundred Double Wasp engine, already a legend, and strapped on a new experimental turbocharger, the C H five. This new turbo, combined with water injection, could force the engine to produce a staggering twenty-eight hundred horsepower in short bursts.

This was War Emergency Power. They also put the plane on a diet, stripping out non-essential equipment and lightening the airframe. The result was a Thunderbolt that looked familiar but flew like nothing else. This P-forty-seven M was designed for one unit and one unit only. The fifty-sixth Fighter Group Zemke’s Wolfpack, the top-scoring group in the Eighth Air Force.

They were the aces and they were the only ones who got this hot rod in level flight at thirty thousand feet. The P-forty-seven M could hit four hundred seventy-two miles per hour. It was a brute-force solution where the T A one fifty-two was the finessed, high-altitude scalpel. The P-forty-seven M was a sledgehammer.

It could use that speed to dive on the new German jets as they were taking off or landing their most vulnerable moments. It retained the legendary eight fifty-caliber machine guns, a wall of lead that could disintegrate anything it hit. But like the T A one fifty-two, the P-forty-seven M was a temperamental beast.

Those new engines were pushed to their absolute limits, and they often failed. Early models were grounded for weeks as maintenance crews worked desperately to fix engine failures. Only one hundred thirty were ever built. They arrived in December nineteen forty-four, and once the engine kinks were worked out, proved to be devastating.

They gave American pilots a fighting chance against the jets and could outrun nearly any other piston-engine fighter the Luftwaffe had left. It was the ultimate expression of the Thunderbolt, a true high-altitude champion. High-altitude speed is one thing, but most dogfights. The brutal turning-and-burning knife fights happened between five thousand and twenty thousand feet here.

A different kind of speed was needed. Not just top-end velocity, but acceleration. The ability to pounce. This brings us to a familiar name. The Focke-Wulf F W one-ninety D-nine. The original Focke-Wulf one-ninety. The Butcher Bird had shocked the Allies in nineteen forty-one. It was a radial-engine brute that outclassed the Spitfire Mark five in almost every way.

But as we mentioned, its BMW radial engine struggled at high altitude. By nineteen forty-three, the tide was turning. Kurt Tank’s solution before the T A one fifty-two was ready was an interim stop-gap. He took the rugged F W one-ninety airframe and did something radical. He replaced the air-cooled radial engine with a liquid-cooled inline V-twelve, the Jumo two-thirteen A.

This completely changed the aircraft to keep the center of gravity. The engine had to be mounted far forward, requiring a long extension. This gave it its famous nickname, the Dora or Long-Nose. The Dora wasn’t just a modified fighter, it was a new breed. It was sleek, powerful, and fast. At twenty-one thousand feet.

It was cleared for four hundred twenty-six miles per hour. This new engine transformed the one-ninety from a low altitude brawler into a true high-performance energy fighter. It could climb better and dive faster than its radial-engine brothers. It was a pilot’s plane, retaining the incredible roll rate and heavy armament of the original, but now it had the speed to match the latest Allied fighters.

When it appeared in the fall of nineteen forty-four, it was a nasty shock to P-fifty-one and Spitfire pilots, who thought they had the measure of the one-ninety. The Dora could meet them on its own terms, using its speed to dictate the fight. It was arguably the best all-around piston fighter the Luftwaffe produced in large numbers during the final year of the war.

About eighteen hundred were built and they fought desperately in the defense of Germany, but the Allies had a response, and it was one of the most powerful fighters of the entire war. The Hawker Tempest Mark five. The British had their own problem the Hawker Typhoon, while a fantastic ground-attack aircraft was too thick and heavy to be a top-tier dogfighter.

Its designer, Sydney Camm, went back to the drawing board. He took the Typhoon’s monstrous engine, the twenty-two hundred horsepower Napier Sabre, and married it to a brand new, much thinner laminar-flow wing. The result was the Tempest, and it was a brute. The Napier Sabre engine was a twenty-four cylinder marvel an H-block engine that was incredibly complex, and in its early days, notoriously unreliable.

But when it worked, it produced a sound unlike anything else in the sky a deep, tearing-canvas roar that was terrifying. The Tempest Mark five could hit four hundred thirty-five miles per hour at nineteen thousand feet, but its real party trick was down low. It was one of the fastest aircraft of the war at sea level, making it the perfect weapon for a new, terrifying threat that emerged in nineteen forty-four the V-one flying bomb.

These buzz bombs were small, jet-powered cruise missiles, and they flew low and fast, too fast for most Allied fighters to catch. But the Tempest could. Tempest squadrons were let loose and they became the V-one’s worst nightmare. Pilots would dive to intercept, cannons blazing. Some, like the famous ace Joseph Berry, would even fly alongside the V-one and use their own wingtip to flip the V-one wing, toppling its primitive gyroscope and sending it crashing into the countryside.

But it was also a deadly fighter in air combat. It was a beast. It could out-dive almost anything. It was fast, heavily armed with four twenty-millimeter cannons and surprisingly agile for its size. In the final year of the war, Tempest squadrons tore through the Luftwaffe, racking up kills against F W one-nineties and M E one-oh-nines, and even claimed over twenty of the new M E two sixty-two jets.

And that brings us to the midway point of our journey. We’ve seen some of the most specialized and powerful aircraft ever built. Let me ask you, of the planes we’ve covered so far. Which one would you have trusted your life to in a dogfight? Let us know your thoughts in the comments. It’s always fascinating to read the firsthand experience and opinions many of you have.

Now we must talk about a legend when most people think of Allied fighters. One beautiful, elliptical wing comes to mind the Supermarine Spitfire. But the Spitfire that won the Battle of Britain in nineteen forty was not the same plane that flew in nineteen forty-five. The original was a delicate, precise fencing foil.

The late-war Spitfire was a broadsword. The problem was that the Spitfire’s beloved Merlin engine, while a masterpiece, was reaching its developmental limit. The answer was a new engine. The Rolls-Royce Griffon. The Griffon was a monster. It was a V-twelve, just like the Merlin, but it was thirty-three percent larger where the original Merlin produced one thousand horsepower.

The Griffon sixty-five engine in the Spitfire Mark fourteen produced over two thousand fifty horsepower. This was a heart transplant, and it changed everything. All that new power and torque meant the plane wanted to rip itself to the left on takeoff. To counter it, engineers had to add a massive new, taller tail fin and rudder.

It now sported a giant five-bladed propeller to turn all that power into thrust. This new Spitfire was a rocket ship. It entered service in early nineteen forty-four and was an absolute revelation. It could climb at over five thousand feet per minute, and its top speed four hundred forty-eight miles per hour.

Suddenly, the Spitfire was back on top. It was faster than the standard F W one-nineties an M E, one-oh-nines. It was one of the few planes that could reliably intercept high-altitude German reconnaissance aircraft. And like the Tempest, it was a fearsome V-one hunter. But more importantly, it was a superb dogfighter.

It combined the classic Spitfire agility with raw, brute-force American muscle. Pilots loved it. It was a war-winner that had been reborn, an old soldier given new life, and it became one of the most respected and feared Allied fighters of the entire war. While the war in Europe was a high altitude arms race, the war in the Pacific was a different theater entirely.

Fights were often at lower altitudes, and the distances were vast. But the most critical moments happened in the first few minutes of an engagement. The scramble. When a Japanese air raid was detected, carrier-based fighters had to get from a cold start on the deck to twenty thousand feet in minutes. Climb rate was life, and the Grumman Ironworks, builders of the tough-as-nails F-four-F Wildcat and the dominant F-six-F Hellcat, took on this challenge.

Their philosophy was simple, and it was classically American build the smallest, lightest airframe possible and then bolt the biggest, most powerful engine they could find to the front of it. The result was the Grumman F-eight-F Bearcat. This airplane was a masterpiece of minimalist, brute-force design. The engine was the same Pratt & Whitney R-twenty-eight hundred that powered the Hellcat and the Thunderbolt, but the Bearcat itself was twenty percent lighter than the Hellcat.

It was tiny, built around the pilot, and the engine. It was so light and so powerful that its performance numbers still seem staggering today. The Bearcat could climb to ten thousand feet in just ninety-four seconds. That’s a climb rate of over six thousand three hundred feet per minute. It was faster than almost any jet of its day.

In a dogfight, it could out-turn and out-climb anything the Japanese had, including the legendary Zero. And its top speed was a blistering four hundred fifty-five miles per hour. The Bearcat was the ultimate expression of the carrier interceptor. It was small, incredibly fast, agile, and still packed a heavy punch with four twenty-millimeter cannons.

But its story is one of tragic timing. The first F-eight-F squadron became operational in February nineteen forty-five, but the war in the Pacific was winding down. Japan’s carrier fleet was at the bottom of the ocean, and its air force was depleted. By the time Japan surrendered in August, the Bearcat had arrived at the front, but it had never seen a single day of combat in World War Two.

It was, perhaps, the finest carrier fighter of the propeller age. Arriving just as the war ended in the postwar years, it became the mount for the Blue Angels and set climb-rate records that stood for decades, but it remains one of the great what-ifs of the Pacific War. We’ve now seen the kings of high altitude and the brawlers of the mid-levels.

But there was one aircraft built in the final, desperate days of the Third Reich that was cut from a completely different cloth. It was an aircraft that broke all the rules. The engineers at Dornier faced a fundamental problem. One engine was good, but two engines were better. The problem was putting two engines on the wings, like in a P-thirty-eight Lightning or a Mosquito created immense drag.

It made the aircraft a huge target and reduced its roll rate. Their solution was one of the most innovative and strangest designs of the war. The Dornier D O three thirty-five, nicknamed the Pfeil or Arrow. This was a push-pull fighter. It had two engines, but they were both mounted in the fuselage, one in the front pulling and one behind the cockpit pushing.

The concept was genius. It gave the plane the power of a twin engine heavy fighter, but with the slim, low-drag profile of a single-engine plane. The two Daimler-Benz D B six-oh-three engines gave it a combined thirty-five hundred horsepower, and the result was simply the fastest piston-engine aircraft to ever fly in Germany.

In level flight, the D O three thirty-five was clocked by Allied test pilots at four hundred seventy-four miles per hour. This thing was a monster. It was fast. It was heavily armed with a thirty-millimeter cannon and two twenty-millimeter cannons. And it was built to last. It was so advanced. It featured one of the very first production ejection seats, because bailing out meant facing that giant propeller at the tail.

But this complexity was its doom. It was a nightmare to manufacture. Development delays meant the first production aircraft were only just starting to reach test units in early nineteen forty-five. Germany was collapsing. Bombing had shattered the supply chains. Perhaps only thirty-seven were ever completed.

None saw true air-to-air combat. They were so fast that when Allied fighters spotted them the D O three thirty-five pilots were simply instructed to apply full power and fly away, which they did with ease. No Allied propeller fighter could catch it. It was an engineering marvel. A glimpse into a parallel future of aviation.

But it was a phantom. It couldn’t be the true king of speed because it never truly fought for the crown. It remains the fastest German prop plane of the war, but not the ultimate champion. That leaves us with one. The final and absolute fastest propeller-driven fighter of the Second World War. By nineteen forty-four, the North American P-fifty-one Mustang was the master of the skies over Europe.

It had the range to fly to Berlin and back and the performance to defeat the Luftwaffe. When it got there, it was, many believe, the most perfectly balanced fighter of the war. But the engineers at North American knew they could do better. They saw the new German jets. They saw the high-altitude T A one fifty-twos, and they saw the brutal power of the new Tempest and Bearcats.

They decided to take their war-winning design and push it to the absolute limit. The result was not just another variant. It was a complete top-to-bottom redesign. This was the North American P-fifty-one H Mustang. The P-fifty-one H was an exercise in lightness. The D model was tough, but the H model was a purebred racer.

Engineers went over every single component. They redesigned the fuselage, simplified the structure, and stripped out nearly fifteen hundred pounds of weight from the airframe. Then they gave it more power. They took the superb Packard built Rolls-Royce Merlin engine and upgraded it to the V-sixteen-fifty-dash-nine model.

This new Merlin had a more advanced supercharger and, crucially, a water-injection system for War Emergency Power. It could produce over twenty-two hundred horsepower. A lighter airframe, a more powerful engine and the most advanced aerodynamic design of the war. The result was the king in official flight tests.

The P-fifty-one H Mustang achieved a top speed of four hundred eighty-seven miles per hour in level flight, at twenty-five thousand feet. This was it, the absolute pinnacle of piston engine fighter design. It was nearly fifty miles per hour faster than the P-fifty-one D that most pilots flew. It wasn’t just fast at the top end.

That weight reduction transformed its handling. It could climb faster, roll faster and turn tighter than any Mustang before it. It retained the P-fifty-one’s legendary long range, meaning it could fly from Iwo Jima to Tokyo, fight and fly all the way back. It was designed for the invasion of Japan. It was the plane that would have met the last of Japan’s fighters over their homeland.

But like the Bearcat, its timing meant it missed the war. Production began in February nineteen forty-five. By the time Japan surrendered in August, five hundred fifty-five had been built, but none had seen combat. They arrived just as the jet age was beginning, but the record stands. While the T A one fifty-two H may have been faster at extreme altitude, and the D O three thirty-five was a what if marvel.

The P-fifty-one H was the fastest all-around production fighter to come out of the war. It was the perfect final expression of a design that had already achieved immortality. So who was the king of speed? As we’ve seen, there is no single simple answer. Was it the T A one fifty-two H, the thin-winged specialist that ruled the stratosphere at four hundred seventy-two miles per hour? Was it the D O three thirty-five the bizarre Arrow that proved a push-pull design could hit an incredible four hundred seventy-four miles per hour,

even if it never had the chance to prove it in a fight. Or was it the P-fifty-one H Mustang? The ultimate American thoroughbred, stripped and supercharged to achieve a documented four hundred eighty-seven miles per hour, the fastest of them all? The truth is, all of these machines were masterpieces. They were designed by engineers and flown by pilots who were pushing the boundaries of what was thought possible, all while under the relentless pressure of a world at war.

Just sixty-one miles per hour separated our number eight plane from our number one in that tiny margin. Thousands of hours of engineering and the lives of countless men were spent. Speed wasn’t everything, of course. The agility of the Spitfire. The toughness of the Thunderbolt. The climb rate of the Bearcat.

These all mattered just as much. But in a war where seconds meant survival, where catching an enemy before he could bomb, or escaping to fight another day was the only thing that mattered. Speed was the ultimate weapon.

News

CH2 . German Aces Once Mocked the P-51 Mustang as a “Laughable Toy” — Until the Sky Above Berlin Exploded with 209 of Them and Turned Arrogance into Terror…

German Aces Once Mocked the P-51 Mustang as a “Laughable Toy” — Until the Sky Above Berlin Exploded with 209…

CH2 . They Ordered Him to Simply Photograph the Target — Instead He Unleashed a One-Man Assault That Obliterated 40 Japanese Aircraft and Shattered Every Rule of Pacific Air Warfare…

They Ordered Him to Simply Photograph the Target — Instead He Unleashed a One-Man Assault That Obliterated 40 Japanese Aircraft…

CH2 . Why Admirals Desperately Banned His “50-Foot Death Charge” — Only for That Same Violent Maneuver to Obliterate 8 Japanese Warships in Just 15 Minutes..?

Why Admirals Desperately Banned His “50-Foot Death Charge” — Only for That Same Violent Maneuver to Obliterate 8 Japanese Warships…

CH2 . How One Tail Gunner’s “Recklessly Savage” Counter-Attack Obliterated 12 Bf 109s in Just 4 Minutes — And Force a Brutal Rethink of Air Combat Tactics Forever..?

How One Tail Gunner’s “Recklessly Savage” Counter-Attack Obliterated 12 Bf 109s in Just 4 Minutes — And Force a Brutal…

ch2 . How a Farm Kid’s Forbidden Counter-Tactic Turned a Doomed Air Battle Into a Massacre of German Fighters — And Miraculously Save 300 Bomber Crewmen from Certain De@th??

How a Farm Kid’s Forbidden Counter-Tactic Turned a Doomed Air Battle Into a Massacre of German Fighters — And Miraculously…

ch2 . The Rifle the Army Tried to Erase — Until One Defiant Farm Boy Used It to Hunt Down Nine Japanese Snipers Before Dawn,…

The Rifle the Army Tried to Erase — Until One Defiant Farm Boy Used It to Hunt Down Nine Japanese…

End of content

No more pages to load