Why the 5th Air Force Ordered Japanese Convoy Survivors to be Strafed in their Lifeboats…?

March 1943, the JN dispatched 16 ships from Rabbal. Their destination was a port of Lee on the island of New Guinea. The convoy was attacked on March 2nd here, and a larger coordinated attack occurred around here on March 3rd. Eight of the eight convoy transports were sunk along with four of the eight destroyers.

This left thousands of troops and seammen in the water. The B-25s used in most of the low-level attacks were the modified C1 models where they sported eight forward-facing Browning M2 50 caliber machine guns. four in the nose cavity and four mounted on the sides. Each gun was fed by 480 rounds of a repeating ammo mix of two armorpiercing, two incendiary, and a single tracer.

These guns were used to suppress a ship’s anti-aircraft fire while on a bombing run, and they were used in strafing the Japanese in the water. This table from a fifth air force Battle of the Bismar Sea report lists a convoy ship’s name, weight, and number of personnel carried. The convoy was transporting around 6,000 Japanese military troops and the cargo supplies were are listed in this table.

Let’s review a couple battle narrations as documented by the bomber crews. This crew report snippet from an April 1943 fifth Air Force Battle of the Bismar Sea report describes a B25 ship attack on March 3rd, 1943. They attacked a destroyer around 10:00 a.m. with a 500lb bomb and then made 15 strafing runs on a lifeboat and survivors in the water.

During the next afternoon, they bombed a destroyer and straed more survivors who were in small life boats and rafts. The March 3rd combat location is here. Most of the ships were sunk here, and this area was teameing with survivors from sunken transports and destroyers. This image shows the four Japanese merchant vessel types from an April 1945 21st Bomber Command Air Intelligence report.

The convoy was a mix of Fox and the larger terror ships. This image from a May 1943 assistant chief of air staff impact document shows a merchant vessel under a B-25 strafing attack during the March 3rd battle. The caption points out there’s eight landing craft located on its upper deck. This model shows a clearer view of the landing craft located on the ship’s deck.

This page from an April 1945 naval intelligence document shows characteristics in an image of the Japanese type B and the larger type A landing craft carried on the cargo ship’s deck. These were placed in the water by the ship’s crane. Given the craft’s speed and endurance, the type B has enough fuel for around 43 mi and the larger type A for 82 m.

This assumes they were fully topped off with fuel. The type B landing craft can carry 30 troops or three tons of cargo and the type A can carry 90 troops or 11 tons of cargo. The Japanese cargo ships and destroyers also have lifeboats like seen in this image or on this Japanese destroyer model. This image from a 2013 Air Force history document on the Battle of the Bismar Sea shows an overhead view of the Japanese destroyer’s lifeboats.

As the ship sinks, the crew may have time to deploy the landing crafts and/or lifeboats if not shot up by the strafing runs or damaged by bombs. This page from a 1945 US Navy document outlining anti-ubmarine tactics describes yubot strafing guidelines. Strafing is to be directed at deck personnel.

The aircraft gunner should also target the yubot’s vital locations. Survivors in the water though are not to be fired upon. In this B25C1 battle narration that occurred on March 3rd at 1:30 p.m., the crew after attacking the ship with their bomb straped the Japanese survivors and floating cargo in the water, which was strewn as far as the eye could see.

A sinking destroyer crew launching a lifeboat was strafed by the bombers’s eight 50 caliber machine guns for a 7-second duration. He stopped firing when the lifeboat was destroyed and the crew were killed. The crew returned on the next day on the 4th at 2:30 p.m. with eight other B25s to seek out and sink the last remaining ship afloat, a destroyer.

After the destroyer attack, they spent 25 minutes draping the Japanese in the water from the previous day’s attack. He points out the devastating effect of the B-25 C1 models, eight forward-facing 50 caliber machine guns cannot be overlooked. In this B-25C1 attack on March 4th at 3 p.m.

the target was a crippled destroyer and Japanese in the water at this location which is around here 40 mi from this shore point. There were around 200 Japanese troops in the water within a two square mile area of the destroyer. They were clinging to ship debris like seen in this image from the reference shown earlier. The destroyer was struck by a bomb.

After the attack, the bomber made three strafing passes at personnel in the water, expending 2500 rounds. On March 5th, air crews were ordered to seek and destroy any remaining personnel in the water by attacking any barges and lifeboats still afloat. These attacks would be conducted by the RAAF squadron 30 bow fighters.

War 15-63J requires the deployment of five bow fighters to attack 10 barges at this position. They are occupied by survivors and cargo. These are the five bow fighters assigned to the mission. Takeoff is at 2:30 p.m. The attack is described on this page. A Hudson was seen attacking a large military landing craft, likely the type A landing craft, and the smaller type B landing craft 20 mi from Lucen Island.

The type B was filled with around 30 troops, and the larger type A craft was filled with at least 30 troops. They wore JA uniforms. Both of the landing crafts were strafed. The Japanese did not jump overboard during the strafing attacks and they were all assumed killed. The water was red and sharks could be seen in the area.

The type B was sunk and the type A was sinking. 20 mi southwest of Capeboard Hunt, another barge holding 30 Japanese was strafed and was sinking. The attack occurred around here at 20 mi from shore. The Japanese may have fired on the plane with small arms. However, the wing hole may have been from a ricochet. Another small barge with six Japanese aboard was strafed and was sinking.

All boats attacked were considered sunk. War order 1463K is listed on this page. Six bow fighters will be sent to seek and destroy 30 lifeboats 30 mi from Kboard Hunt on March 5th. These are the RAF bow fighters sent on this mission. Group A 10 mi west of Kport Hunt was comprised of five type B landing craft and a small boat.

Four of the type B boats were filled with 25 Japanese and one was filled with cargo. All boats were aggressively strafed and destroyed. In this case, the Japanese jumped overboard prior to strafing. This spared the crews of witnessing the carnage that crews from the war 15 attacks observed. Group B was comprised of 14 rafts, each loaded with 12 men and four lifeboats, each with six men.

Two of the lifeboats were sailing toward shore. The lifeboats were only partially filled, suggesting they may have been manned by officers. All boats were strafed. A barge from group A did return fire from a submachine gun or light machine gun. The air crews pointed out that the order to strafe the undefended boats was understood.

They carried out the orders to destroy the craft and kill the occupants. However, these strafing attacks were considered distasteful from a 1995 US Air Force history and museum programs document discusses the post battle operations. From March 4th and on, the Allies hunted the Japanese battle survivors by either PT boats or aircraft.

An RAAF pilot pointed out, “For every Japanese kill, that is one last the army may have to face.” This historian remarked, “The Japanese do not surrender. They were within swimming distance from the shore and could rejoin the lake garrison.” I would push back on the statement the survivors were within swimming distance from the shore, as they were more like 10 to 40 m from the shore.

3,000 of the 6,900 convoy personnel died by bombing, scraping, exposure, thirst, and/or shark attack. This page from a November 2007 World War II magazine article justifies the post battle attacks on the Japanese survivors. Over the next few days, post March 3rd, the Allies were sent to the battle zone to search and destroy any ship survivors.

General Kenny ordered them to strafe the lifeboats and rafts. These were mopping up operations. On March 20th, he claimed the missions will stop that night. Any survivors not killed will be at or beyond 30 mi from landfall in sharkinfested waters, not likely to survive. Many air crew reports were logged claiming barge 200 survivors attacked no survivors.

Kenny’s chief of staff pointed out the Japanese set the pace for no quarter after strafing parachuting B7 crew members. This event was witnessed and shared throughout the fifth air force and was used by some air crews to justify the strafing of the Japanese. However, others justified the killings were a military necessity. At the time, the strafing of the Japanese was not considered controversial.

The public was supportive of the tactic as one officer pointed out. The enemy is out to kill you and you the enemy. You cannot be sporting in war. Life magazine featured General Kenny on its March 22nd, 1943 cover as seen here with headline Victor of Bismar Sea. Reconnaissance of the battle area showed many Japanese survivors in the water.

Commanders ordered airmen to attack these personnel. The goal was to keep them from reaching New Guinea and joining the war effort. This was clearly not a rescue mission, but a seek and destroy mission. Many were on lifeboats and landing craft. The landing craft could be considered war material and legitimate military targets.

Most Japanese were found in lifeboats, rafts, or clinging to debris. There was no way to rescue the Japanese by air. The Japanese swam away from the PT boat sent during the night raids. Their Bashidto warrior code made surrendering difficult. Present- day war fighters may struggle with this decision made 83 years ago.

Back then, the rationale it was a military necessity to kill a Japanese soldier rather than face him in a future battle. The airmen returned to the battle area for mopping up operations, as discussed on this page from a 1996 US Air Force document on the air war in the Southwest Pacific during World War II, where mopping up was a term for locating and strafing any Japanese found in the water.

Airmen justified their actions as payback for Japanese atrocities, past, present, and future. Others felt it was an easy way to reduce the number of Japanese soldiers, which may lead to the war ending sooner. General Kenny’s attitude was expressed in these thoughts. The Japanese asked for no quarter and expect none. He thought the Japanese were tough fanatics, not aligned with civilized belligerance.

Some air crews found the strafing missions distasteful. Others thought their actions were not unlawful or immoral. A Japanese survivor recalled, “Most of the shipwreck survivors were killed. The survivors had to deal with aircraft attacks and sharks. Many of the survivors were drifting with the winds and currents.

Some of the type A and B powered landing crafts did attempt to reach New Guinea. Channel commentary. I believe strafing of the shipwreck survivors can be militarily justified under certain conditions. If a powered landing craft full of armed troops and provisions is headed to shore, then yes, straping is justified.

However, unarmed Japanese and non-powered lifeboats 40 mi from shore or on floating debris shot up by PT boat crews at point blank range can’t be justified unless they refuse to surrender. There are definitely shades of gray between these two scenarios. Based on the combat narrations and rational given, do you believe these attacks on the Japanese were warranted? If you found this Battle of the Bismar Sea strafing Japanese survivors video interesting and thoughtprovoking, please consider liking, commenting, and or subscribing to World War II US Bombers.

News

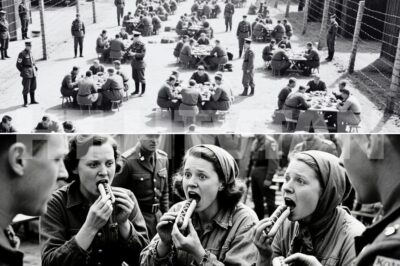

CH2 . Camp Florence, Arizona. July 1944. The 4th of July celebration smelled of charcoal and frying onions. And Sergeant Maria Kaufman watched the American guards set up a strange assembly lying metal grills, split bread rolls, pink sausages that looked nothing like German worst.

Camp Florence, Arizona. July 1944. The 4th of July celebration smelled of charcoal and frying onions. And Sergeant Maria Kaufman…

CH2 . Starving German POWs Couldn’t Believe What Americans Served Them for Breakfast… May 17th, 1943, Northern England. Cold mist hung low over the railard, wrapping the countryside in a damp, gray silence. The cattle cars hissed as steam curled from beneath their iron wheels. Inside, 180 German soldiers waited, cramped and sleepless after 3 days of transport from the ports of Liverpool.

Starving German POWs Couldn’t Believe What Americans Served Them for Breakfast…May 17th, 1943, Northern England. Cold mist hung low over…

CH2 . How American B-25 Strafers Tore Apart an Entire Japanese Convoy in a Furious 15-Minute Storm – Forced Japanese Officers to Confront a Sudden, Impossible Nightmare…

How American B-25 Strafers Tore Apart an Entire Japanese Convoy in a Furious 15-Minute Storm – Forced Japanese Officers to…

“When I saw my husband and his mistress cutting the pregnant wife’s hair, I felt something break inside me. She cried: ‘Why are you doing this to me?!’ and he only replied coldly: ‘You deserve it.’ In that instant, I knew I couldn’t stand idly by. I, his mother, prepared my revenge… and they still don’t imagine how much they will pay. Do you want to know what happened next?”

“When I saw my husband and his mistress cutting the pregnant wife’s hair, I felt something break inside me. She…

A MILLIONAIRE GAVE A USELESS HORSE AS A JOKE, BUT HE BITTERLY REGRETTED IT. Once upon a time, in a small town where laughter came easily and life was simple, there lived a man who believed money could buy anything. His name was Arnaldo Montiel, a young millionaire known for his arrogance and his desire to show off his power.

A MILLIONAIRE GAVE A USELESS HORSE AS A JOKE, BUT HE BITTERLY REGRETTED IT.Once upon a time, in a small…

“Mom, I have a fever… can I stay home from school today?” the girl asked. Her mother touched her forehead and allowed her to stay home. By noon, the girl heard the sound of a key turning in the lock. Peeking out from her room, she saw her aunt walk in and secretly slip something into her mother’s coat pocket. Before leaving, her aunt spoke on the phone and said, “I’ve handled everything. Tonight she can call the police. That fool won’t suspect a thing.”

“Mom, I have a fever… can I stay home from school today?” the girl asked. Her mother touched her forehead…

End of content

No more pages to load