Why Churchill Refused To Enter Eisenhower’s Allied HQ – The D-Day Command Insult…

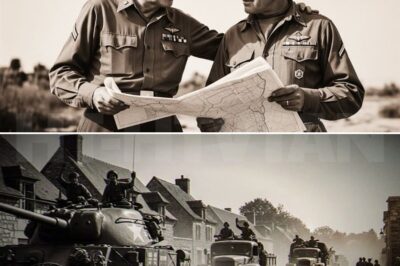

The rain came down in sheets that morning in late May 1944, turning the grounds of Southwick House into a morass of mud and anxiety. Inside the elegant manor house that served as Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, General Dwight Eisenhower sat hunched over maps that showed the beaches of Normandy with an intimacy that bordered on obsession.

He had not slept well in weeks. The weight of what was coming pressed on him like the low clouds that threatened to postpone the invasion yet again. Every decision flowed through this room, every order bore his signature, and if the enterprise failed, if those young men drowned in the channel, or were cut down on the beaches, it would be his name that history cursed.

What troubled him that particular morning was not the weather forecast or the latest intelligence about German positions. It was Winston Churchill. The prime minister had informed him through intermediaries that he intended to observe the invasion from HMS Belfast to stand on the bridge of that cruiser and watch the greatest amphibious assault in history unfold with his own eyes.

Eisenhower understood the impulse he himself would have preferred to be in the first wave to share the danger with the men whose lives he was risking. But Churchill’s presence would create chaos. The ship’s captain would be paralyzed by the responsibility of protecting Britain’s wartime leader. Command decisions would be filtered through political considerations.

And if Churchill died, if a German shell found that particular cruiser among the hundreds of vessels in the Armada, the psychological blow to Britain and the alliance might prove as devastating as a military defeat. Eisenhower had tried reasoning with Churchill. He had sent messages through General Montgomery and Admiral Ramsay.

He had even contemplated confronting the prime minister directly. But Churchill had a way of overwhelming objections with rhetoric and will. The man who had stood alone against Hitler in 1940 was not easily deterred once his mind was set. So Eisenhower did something that would never appear in the official histories.

He called on an American colonel named James Whitmore, a man whose specialty was what the military euphemistically called unconventional operations. Whitmore had parachuted into occupied France, had organized resistance cells, had done things that earned him medals he could never wear in public. The orders Eisenhower gave were simple and impossible.

Churchill was not to board HMS Belfast. How Witmore accomplished this was his own concern. Eisenhower would deny any knowledge of the operation. If it went wrong, Witmore would face court marshall and disgrace, but Witmore had seen photographs of Bellson and Dao that most people would not see until after the war ended. He knew what was at stake.

He accepted the mission without hesitation. The solution Whitmore devised was elegant in its simplicity. He could not physically prevent Churchill from boarding the ship. Such an action would create an international incident and probably end with Witmore in the Tower of London. Instead, he created a phantom headquarters.

Working through contacts in British intelligence who owed him favors from previous operations, Whitmore spread a rumor that Eisenhower had established a forward command post aboard HMS Rodney, another capital ship that would be in the bombardment force. This headquarters, the rumor went, would coordinate realtime decisions during the invasion.

It would be the nerve center of Operation Overlord, the place where history would be made. The rumor was carefully calibrated to appeal to Churchill’s sense of drama and his desire to be at the center of events. It was also calculated to trigger his pride. If Eisenhower had established a forward headquarters on a British ship without consulting him, it was an insult to British sovereignty and leadership.

Churchill, already sensitive about the fact that an American had been chosen as supreme commander rather than a British general, would not tolerate being excluded from such a facility. He would insist on inspecting this headquarters. He would demand access as prime minister and as the man who had carried Britain through its darkest hours.

The rumor reached Churchill through three separate channels within 24 hours. His response was predictable. He sent a message to Eisenhower’s headquarters requesting permission to visit HMS Rodney and observe operations from what he called the forward command facility. The message was polite but firm, the kind of request that was really a demand.

Eisenhower, who had been briefed by Whitmore, sent back a courteous refusal. Security concerns, he explained. The forward headquarters was highly classified. Even the king did not know its precise location. Churchill’s presence would compromise operational security. The refusal infuriated Churchill exactly as Whitmore had predicted.

The prime minister dictated a heated response that his staff wisely suggested he reconsider, but the seed had been planted. Churchill now believed that Eisenhower was operating a secret command structure that excluded British oversight. His focus shifted from witnessing the invasion to asserting British prerogatives in the command structure.

He began demanding meetings, insisting on clarifications, pushing for changes to the command arrangements that would give British officers more direct authority. It was King George V 6th who ultimately resolved the crisis, though not in the way history records. The king wrote Churchill a personal letter on the 31st of May appealing to the prime minister not to go to sea on D-Day.

The letter was gracious and heartfelt, pointing out that the king himself had wanted to observe the invasion, but had been persuaded to remain in England. If Churchill went, the letter argued, it would not be fair to the king, who, as a former naval officer and veteran of Jutland, had an equal claim to witness history.

The letter had its intended effect. Churchill backed down, unable to risk both himself and the monarch. What history does not record is that King George wrote that letter at the suggestion of Colonel Witmore, who had been introduced to the king’s private secretary through the same intelligence networks that had helped spread the rumor about HMS Rodney.

Whitmore never claimed credit for the operation. His role remained classified until long after his death. But in the chaotic weeks before D-Day, he had accomplished his mission. Churchill stayed in England. Eisenhower maintained control of the invasion without political complications and HMS Belfast fired some of the first shots on the 6th of June without carrying the prime minister on her bridge.

There was one detail that Witmore never anticipated. On the morning of D-Day, as the invasion force approached the French coast, a young signals officer aboard HMS Rodney noticed something odd. There were no additional communications equipment on board, no expanded staff, nothing that would indicate the presence of a forward headquarters.

He mentioned this to his captain, who made inquiries. Within hours, the story of the phantom headquarters began to unravel. Someone had spread false information about command arrangements for Operation Overlord. It was the kind of deception that could be seen as brilliant or treasonous, depending on one’s perspective.

The investigation that followed was quiet and thorough. It traced the rumor back through various channels, but could never quite identify the source. Whitmore’s name appeared in some reports, but there was no evidence linking him to the deception. Eisenhower, when asked directly, said he had never authorized the establishment of a forward headquarters aboard HMS Rodney and had no idea how such a rumor had started.

The investigators eventually concluded it had been a genuine misunderstanding, perhaps a garbled communication in the hectic days before the invasion. The file was closed. The matter was forgotten. Churchill never learned that he had been manipulated. He believed to his dying day that King George’s letter had changed his mind, that he had made a noble sacrifice by remaining in England during the invasion.

He did eventually visit Normandy 6 days after D-Day aboard the destroyer HMS Kelvin and he made certain the ship participated in the bombardment of German positions while he stood on the bridge. It was his way of claiming a piece of the history he had been denied on the 6th of June. Eisenhower carried the secret with him to the White House and beyond.

In his memoirs, he wrote about the challenges of coalition warfare, the need to balance national sensitivities with military necessity. He never mentioned Colonel Whitmore or the Phantom headquarters. Some lies he believed served a greater truth. The invasion succeeded. The beaches were taken. The liberation of Europe began.

If a small deception had helped make that possible, it was a price he was willing to pay. Colonel Whitmore returned to France 2 weeks after D-Day, parachuting behind German lines on another mission that would never be fully declassified. He was killed near con in July when his resistance cell was betrayed to the Gestapo.

The citation for his postumous medal mentioned his courage and devotion to duty but said nothing about phantom headquarters or prime ministers. His widow received a flag and a pension. His children grew up knowing their father had been a war hero but never learning the details of what he had done. Years later, Whitmore’s daughter would find a letter among her father’s effects, written but never sent, dated the 3rd of June, 1944.

In it, he reflected on the mission he had just completed, the deception he had orchestrated against Britain’s prime minister. The letter revealed a man wrestling with conscience, questioning whether the ends truly justified the means. He wrote about meeting Churchill once briefly at a reception in 1943, how the prime minister had spoken to him with genuine interest about his experiences in France, how Churchill’s hands had trembled slightly as he lit his cigar, betraying an exhaustion the public never saw. Whitmore wrote that he

understood Churchill’s desire to be present at the invasion, that any warrior would feel the same, that there was something cruel in denying an old lion his final hunt. But he also wrote about the young men he had trained for covert operations. Boys really 18 and 19 years old who would be landing on those beaches with everything to lose and nothing yet gained from life.

Their safety, their chances of survival mattered more than Churchill’s pride or his own moral comfort. The mission came first. It always came first. The letter ended abruptly, as if Witmore could not find words adequate to the complexity of what he felt. His daughter kept it in a drawer for decades, never showing it to historians, never speaking of it publicly.

Some truths, she decided, were too painful to share, too tangled in loyalty and betrayal to be reduced to historical record. The irony is that Churchill’s instinct was right. He should have been there, not on HMS Belfast during the invasion, where he would have been a distraction and a liability, but in the planning rooms where strategy was forged, in the councils where decisions about the second front had been debated for years.

Churchill had pushed for the invasion of North Africa, for the campaign in Italy, for the grinding attrition that wore down German strength and made Normandy possible. His vision of peripheral strategy which American commanders had initially resisted had proven correct. By the time the allies landed in France, the Vermacht was exhausted from fighting on multiple fronts.

The Luftvafa was shattered and Germany’s industrial capacity was being demolished by strategic bombing. None of that would have been possible without Churchill’s stubborn insistence on bleeding the enemy before attempting the decisive blow. Yet on the day when his strategy came to fruition, when Anglo-American forces landed on the beaches he had been planning to liberate since 1940, Churchill was in London, pacing the cabinet war rooms, waiting for news.

He had been excluded from the moment of triumph by a deception that played on his pride and his fears about American dominance of the alliance. The man who had threatened to resign over strategic disagreements, who had battled with his own chiefs of staff, and browbeaten Roosevelt and stood up to Stalin, had been outmaneuvered by a colonel he never met, and a phantom headquarters that never existed.

There is something profoundly human in this forgotten moment of the war. We remember the great speeches and the strategic decisions, the battles and the conferences where the fate of nations was decided. We forget the small deceptions, the white lies, the manipulations that made history possible. Eisenhower needed to keep Churchill away from the invasion force, not because Churchill lacked courage or judgment, but because his presence would have complicated an operation that was already impossibly complex. So, a rumor was started, a

fiction was created, and the prime minister, who had saved Western civilization, was tricked into staying home like a child, excluded from the adult table. The tragedy is that Churchill never needed to prove his courage. He had already done that during the Blitz, when he walked through bombed streets and refused to retreat to bunkers while London burned.

He had proven his strategic vision in the dark days of 1940 when Britain stood alone. But he needed to be there to witness, to participate, because he could not quite believe that the invasion would succeed without him. The man who had such faith in the British people who had inspired them with words about fighting on beaches and never surrendering did not have quite enough faith in the military machine he had helped to create.

He thought his presence was necessary for success when in fact his absence was required. This is the paradox that haunts all great leaders in the end. The very qualities that make them indispensable in crisis. the supreme confidence, the refusal to accept defeat, the conviction that they alone can save the nation.

These same qualities make them unable to step aside when their moment has passed. Churchill was the right man for 1940 for the desperate improvisation and defiant rhetoric that kept Britain in the war. But D-Day required careful planning, massive coordination, and cold calculation of casualties and logistics. It required Eisenhower’s methodical competence, not Churchill’s inspired improvisation.

The war had moved beyond Churchill, even as he refused to acknowledge it. So, he was kept away by a phantom, and the invasion succeeded without him. And perhaps that is the real victory. Not just the military triumph of D-Day, but the proof that the cause was larger than any single man, even a man as extraordinary as Winston Churchill.

The young soldiers who landed on those beaches, most of them born after the First World War, carried in their packs the future Churchill had fought to preserve. They did not need him on HMS Belfast to inspire them. They had his words already, carried in memory and spirit. They knew why they were there. And when they waded through the surf into German machine gun fire, they did so not for Churchill or Eisenhower or any general or politician, but for the simple idea that tyranny must be opposed and that free people will fight to remain free. Colonel Whitmore

understood this in a way that neither Churchill nor Eisenhower quite did. He had worked with the French resistance, with ordinary people who risked everything to fight the occupation. He knew that courage was not the property of prime ministers or generals, but was distributed democratically among all people who chose to resist evil.

So when he created the phantom headquarters that kept Churchill away from the invasion, he was protecting not just the operation, but the idea that the invasion represented. This was not one man’s war anymore. It was everyone’s war, and everyone had a role to play, including the role of stepping aside when necessary.

What haunted Whitmore in those final weeks of his life, as he moved through the Norman countryside, organizing ambushes and sabotage operations, was the realization that he had become what he fought against. The Nazis built their power on lies, on propaganda, on the manipulation of truth for political ends. And here he was, an American officer who believed in democracy and transparency, who had sworn an oath to uphold the Constitution, spreading deliberate falsehoods to manipulate the leader of an Allied nation.

The fact that his deception served a noble purpose, did not entirely absolve him. He had crossed a line that should not be crossed, had set a precedent that troubled him deeply. If it was acceptable to lie to Churchill to protect the invasion, what other lies might be justified in the name of victory? Where did noble deception end and tyranny begin? These questions followed him through the hedge of Normandy, whispered to him in the moments before sleep, and perhaps they were still with him when the Gestapo came, when he faced the final

interrogation that he knew would end in execution. His last words, according to a French resistance fighter who survived the raid, were not defiant or heroic, but strangely apologetic, as if he were asking forgiveness for sins no one else knew he had committed. The reflection that haunts this forgotten story is about the price of greatness and the cost of vision.

Churchill gave Britain everything he had. He burned himself out in service to his country, and when the moment came for him to witness the triumph he had made possible, he was excluded by a lie that served a greater truth. There is heroism in that exclusion, a heroism of restraint and sacrifice that is harder to recognize than the heroism of action.

Churchill stayed home and young men died liberating France and the world turned on its axis toward a future that neither Churchill nor those young men would fully recognize. We remember D-Day as a triumph and rightly so. But within that triumph were a thousand small tragedies, a thousand sacrifices that had nothing to do with bullets or artillery shells.

Churchill’s sacrifice was that he was denied his moment of glory by men who understood that his presence would endanger the cause he had fought to preserve. He accepted that denial, however unwillingly, because in the end he was enough of a democrat to submit to authority he had helped to create. That submission, that willingness to be sidelined by the machinery of modern warfare, may have been his greatest contribution to the victory.

Not the speeches or the strategy, but the simple act of staying away when his instincts screamed at him to be present. Sometimes the hardest thing a hero can do is nothing at all. And sometimes that nothing is the most heroic act of all.

News

CH2 . What Eisenhower Said When Patton Broke the One Order He Wasn’t Allowed To… Again… Stop. That was the order.

What Eisenhower Said When Patton Broke the One Order He Wasn’t Allowed To… Again… Stop. That was the order. One…

Why German POWs Begged America to Keep Them After WWII…? In the final agonizing months of the Second World War, the German weremocked. Once the seemingly invincible conqueror of Europe was a hollowedout shell. On the Western front, American, British, and Allied forces had breached the Rine. Their industrial might and unstoppable avalanche.CH2 .

Why German POWs Begged America to Keep Them After WWII…? In the final agonizing months of the Second World War,…

CH2 . What Hitler’s Generals Said the Moment Romania Betrayed Him Overnight… They thought they had already seen the worst. They had watched an entire army freeze outside Moscow.

What Hitler’s Generals Said the Moment Romania Betrayed Him Overnight… They thought they had already seen the worst. They had…

CH2 . What Hitler Said When Germany’s Last Oil Fields Fell to the Soviets February 1945, the maps in the Fura bunker showed Soviet forces closing on the Hungarian oil fields near Lake Balaton, and Adolf Hitler studied the fuel production reports with the intensity of a man reading his own death sentence.

What Hitler Said When Germany’s Last Oil Fields Fell to the Soviets February 1945, the maps in the Fura bunker…

MY COUSIN SMILED WHILE MY SON TURNED BLUE — AND WHEN THE RESTAURANT’S CAMERAS EXPOSED WHAT SHE REALLY DID, EVEN THE POLICE STEPPED BACK AND SAID, ‘THIS WASN’T AN ACCIDENT.’…

MY COUSIN SMILED WHILE MY SON TURNED BLUE — AND WHEN THE RESTAURANT’S CAMERAS EXPOSED WHAT SHE REALLY DID, EVEN…

The Night My Wellness-Guru Sister-in-Law Replaced My Blood Pressure Medication With Poisonous Sugar Pills… All Because She Wanted to ‘Expose a Faker’ and Turn My Collapse Into Her Big Viral Moment…

The Night My Wellness-Guru Sister-in-Law Replaced My Blood Pressure Medication With Poisonous Sugar Pills… All Because She Wanted to ‘Expose…

End of content

No more pages to load