Why Admirals Desperately Banned His “50-Foot Death Charge” — Only for That Same Violent Maneuver to Obliterate 8 Japanese Warships in Just 15 Minutes..?

In 1943, when Allied High Command first examined Major Ed Larner’s proposed attack method, they did not view it as bold or innovative or even marginally feasible; they saw it as a reckless, uncontrollable plunge into certain death, a maneuver so violent and so far outside every accepted doctrine of aerial warfare that the admirals immediately stamped it with one definitive label—a suicide run—and banned it outright. They banned it again when Larner tried to refine it. They forbade him to practice it, to train crews in it, even to speak about it as a legitimate tactic. But Larner—and his commanding officer, General George Kenney—understood something far darker and far more urgent than the cautious calculus of headquarters. They understood that the existing strategy had already failed, catastrophically, and in the waters north of New Guinea, more than 7,000 Japanese troops were sailing southward at that very hour. Every single soldier who reached the shoreline would mean more American and Australian lives lost in the thick, punishing jungles at dawn on March 1st, 1943.

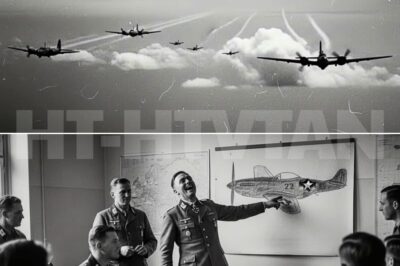

On that grim morning, twenty-five-year-old Major Ed Larner stood on the slick coral runway at Port Moresby. He had flown seventy-two combat missions already, a staggering number for a man his age, and despite all the risks his crews had taken, not one of those missions had succeeded in sinking a major Japanese ship. That failure was not his alone; it was a crisis that gripped the entire Fifth Air Force. For eight relentless months, B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-25 Mitchells had followed official doctrine to the letter, swooping in at the prescribed altitude of ten thousand feet and releasing their bombs according to the standard playbook. The results were devastatingly clear: a hit rate of three percent. Ninety-seven out of every hundred bombs splashed uselessly into open ocean, sending up towering plumes of water that looked dramatic in gun-camera footage but failed to do anything to the Japanese fleet advancing relentlessly toward Allied positions.

The mathematics were brutal, and they were unchanging. A 1,000-pound bomb released from 10,000 feet fell for thirty-seven seconds before striking the water. In those thirty-seven seconds, a Japanese destroyer moving at thirty knots could travel 380 yards, nearly four football fields of distance. A bombardier could aim perfectly at the ship’s exact location and still miss cleanly because the vessel had already surged far beyond the strike point by the time the bomb arrived. Over and over again, Larner watched the same heartbreaking pattern unfold. Crews landed exhilarated, convinced they had delivered killing blows. Gun cameras showed symmetrical bomb patterns erupting right around Japanese ships—close enough to look lethal but never close enough to actually penetrate steel. Again and again, the ships sailed on, entirely operational, their wakes foaming defiantly behind them.

The Japanese, however, were not missing. Their gunners, drilled in shipboard anti-aircraft fire with grim precision, had more than enough time to track the slow, predictable approaches of the high-altitude bombers. They calculated perfect leads and bracketed entire bomber formations with walls of flak. They adjusted their fire without hurry, knowing they had dozens of seconds to correct their aim. And while the Americans missed the ships, the Japanese rarely missed the bombers. In the preceding month alone, Larner’s squadron had lost four aircraft to this doctrine. Forty men. Forty families awaiting telegrams that would shatter their lives. All because the Allied approach to anti-shipping attack simply did not work.

This failure was the crucible that pushed General Kenney to propose something so unorthodox, so violently different, that experienced pilots dismissed it the moment they heard it. Kenney said the solution was not to drop the bomb. It was to throw it.

He wanted his pilots to skip the bomb across the surface of the water—intentionally—like a flat stone.

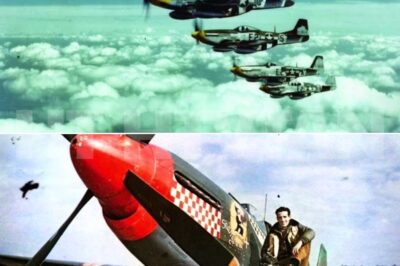

The plan was simple in concept yet terrifying in execution: fly the B-25 Mitchell at just 50 feet above the waves, so low that the aircraft’s belly almost skimmed the tops of the swells, and then charge directly at the enemy ship. Close the distance to roughly three hundred yards. Release the 1,000-pound bomb fitted with a five-second delayed fuse. Let the bomb’s tremendous forward momentum hurl it across the surface of the ocean. It would bounce once, perhaps twice, like a skipping stone thrown with deadly precision, before smashing directly into the destroyer’s hull and detonating at or below the waterline—the precise location where a ship was most vulnerable.

Physics theorists insisted it would work. Every calculation suggested the method could deliver devastating results.

But the pilots who would have to fly it—the men who would race broadside into a warship armed with batteries of rapid-fire guns—believed it was madness.

After all, flying a fifteen-ton twin-engine bomber at fifty feet off the ocean surface meant navigating a constantly shifting landscape of waves, spray, wind shear, and enemy fire. And doing so straight toward a destroyer fully loaded with anti-aircraft guns meant offering the enemy a target so close and so exposed that survival felt almost theoretical.

Yet Larner knew the reality with a clarity that no mathematical model could soften. The high-altitude method had already cost too many aircraft and too many men, and it would cost countless more if nothing changed. The Japanese convoy steaming toward New Guinea would land its thousands of troops without hesitation unless someone found a way to hit the ships directly—and soon. The jungle fighting that would follow would be horrific. The stakes were no longer strategic; they were painfully human.

So the question was not whether the new tactic was dangerous.

It was whether it was the only tactic that might work.

Larner had seen the failures. He had felt the losses. He had watched the Japanese gunners tear apart American formations while the bombs harmlessly carved geysers of water around the ships. And as he looked out across the runway at Port Moresby that morning, he understood something with a heavy, unshakable certainty:

If the conventional approach continued, nothing would save the Allies from disaster.

What happened next—how the tactic exploded into reality, how the low-altitude runs shattered Japanese defenses, how eight ships fell within fifteen minutes—began with a single decision to defy the ban and trust the only method that offered even a sliver of hope.

But at that moment, standing on the coral runway, the outcome was anything but certain.

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

In 1943, Allied High Command looked at Major Ed Larner’s new tactic and called it reckless. They called it a suicide run. They banned it twice, forbidding him from even practicing it. But Larner and his boss, General George Kenney, knew a terrible truth. The conventional way of fighting wasn’t working, and 7000 Japanese soldiers were, at that very moment, steaming south to reinforce New Guinea.

Every single man in that convoy who made it ashore meant more American and Australian blood would soak the jungle floor at 630 in the morning, March 1st, 1943. That 25 year old major stood on the wet coral runway at Port Moresby. He’d already flown 72 combat missions, and in all that time, his crews hadn’t sunk a single major ship.

This was the crisis for the entire Fifth Air Force. It wasn’t for lack of trying. For eight agonizing months, B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-25 Mitchells had been flying by the book, attacking Japanese convoys from 10,000ft. Their hit rate was a miserable 3%. Think about that. 97 out of every 100 bombs dropped missed.

They splashed harmlessly in the vast, empty ocean while the Japanese ships, untouched, steamed right on through. The mathematics were just brutal. A 1,000 pound bomb dropped from that altitude took 37 seconds to hit the water. In those 37 seconds, a Japanese destroyer moving at 30 knots could cover 380 yards.

That’s nearly four football fields. The bombardier would aim perfectly at where the ship was. By the time the bomb arrived, it hit nothing but the ship’s white, churning wake. Larner had seen it time and time again. Crews would come back exhilarated, claiming direct hits. They’d even have the gun camera footage to prove it.

Perfect photos of bomb patterns exploding right around the ships. But a round wasn’t on. The Japanese just kept sailing. But the Japanese gunners weren’t missing. They shot down the high altitude bombers with methodical, lethal precision. While American pilots were lining up their 37 second drop, Japanese gunners had all the time in the world.

They tracked the approach. They calculated the lead, and they bracketed the bomber formations with curtains of flak. Larner’s own squadron had lost four aircraft in the last month trying this failed tactic. 40 men, 40 families back home who would get a telegram because of a strategy that just didn’t work. This failure is why General Kenney, commanding the Fifth Air Force, had proposed something that sounded utterly insane to every seasoned pilot who heard it.

He said, don’t drop the bomb. Throw it. He wanted his pilots to skip the bomb across the water like a flat stone. The plan was simple, and it was terrifying. Fly in just 50ft off the waves. Race straight at the ship at 300 yards. Release the bomb, which had a five second delay fuse. The bomb’s own momentum would carry it across the water.

It would skip once, maybe twice, and slam directly into the ship’s hull. It would detonate right on the waterline or just underneath it, tearing the heart out of the vessel. The physics theorists said it would work. The pilots who had to fly it said it was suicide. Flying a 15 ton twin engine bomber 50ft off the ocean, straight into the teeth of a Japanese destroyer bristling with guns.

It violated every survival instinct a man had. Those destroyers weren’t sitting ducks. They carried 127 millimeter main guns, 25 millimeter cannons, and dozens of machine guns. And all of them could track a bomber flying that low. One good hit to an engine, and the B-25 would cartwheel into the sea before the crew even knew they were hit.

This was the kind of impossible choice these men faced every day. If you believe their stories deserve to be remembered, take a second to hit that like button. It truly helps us ensure this history isn’t forgotten because it was so dangerous. High command had banned the tactic twice. Larner’s request to practice skip bombing in December and again in January were both denied.

The official response called it a reckless disregard for equipment and personnel. Crews were ordered to focus on proven high altitude tactics, but those proven tactics weren’t sinking ships and the Japanese convoy was getting closer. This was the moment of truth. Larner had to make a choice, obey orders, and let the 7000 troops land, guaranteeing a bloody, protracted fight in the jungles, or defy the ban and risk 60 of his men on a tactic that might be a death sentence.

Larner didn’t make the choice alone. General Kenney had seen this coming. He had given his men a new tool. Fifth Air Force mechanics under a man named Pappy Gunn had done something revolutionary. They took the B-25 Mitchell, a medium bomber, and ripped the bombardier’s station out of its glass nose. In its place, they bolted eight forward firing 50 caliber machine guns.

They added four more in blisters on the fuselage. Suddenly, the B-25 wasn’t just a bomber. It was a flying gun platform, a strafing gunship that could pour 200 rounds of 50 caliber lead into a target every second. The theory was simple. Suppress the enemy’s guns. You couldn’t just fly at a destroyer and hope they missed.

You had to give those Japanese gunners a reason to duck. Make them choose between returning fire and staying alive. Larner had watched them bolt the guns on three weeks earlier. It added 1,200 pounds. It shifted the plane’s center of gravity. It turned his bomber into something that had never existed before in the history of warfare.

And this is where Larner and Kenney had taken their biggest risk. Despite the official ban, they had practiced in secret. Kenney had found the perfect target the wreck of the Pruth, a 4700 ton steamer that ran aground near Port Moresby back in 1924. It sat there rusting and half submerged. A perfect stationary target.

Larner’s crews flew practice runs at dawn and dusk, when the light was poor and prying. Eyes from headquarters were few. They learned how to skim the wave tops at 270 miles an hour. They learned to judge the distance by eye, and they learned what happens when you get it wrong. Lieutenant Jake Faucet had gotten it wrong on February 16th.

He came in too high, 70ft instead of 50. His bomb skipped twice, cleared the Pruth entirely, and exploded harmlessly 300 yards beyond it. A total miss Faucet’s bombardier sergeant Mike Russo, recalculated lower, faster, a closer release point. On the next run, Faucet came in at 45ft. The bomb skipped once and slammed into the Pruth’s hull right at the water line.

It was a perfect hit, right where a ship’s engine room or magazine would be, right where one bomb could detonate a thousand tons of enemy ammunition and blow a warship in two. But there was one terrifying difference the Pruth wasn’t shooting back. Now, standing in the operations tent Larner spread the reconnaissance photos across the planning table.

The convoy was spotted at dawn steaming through the Bismarck Sea. Eight fat transports packed with soldiers, artillery and ammunition. Eight destroyers screening them. Every officer in that tent knew what this meant. They remembered the battle for Buna just months earlier. Japanese reinforcements there had turned a short fight into a six month nightmare that cost 5000 Allied lives.

If this convoy got through, Lae would be Buna all over again. But worse. Larner laid out the plan. They had been forbidden to practice. He assigned every pilot a specific target. Transport one through eight. The Royal Australian Air Force would go in first. Their Beaufighters would strafe the convoy, a distraction to suppress anti-aircraft fire.

Then B-17s would bomb from high altitude. This wasn’t to sink them. It was to scatter them, to force the Japanese captains to break formation and start evasive maneuvers, making them isolated targets and then Larner’s. Nine B-25s would come in 50ft. The killing blow. The math had to be perfect approach at 50ft speed at 270mph.

Release at 300 yards. Fuse set for five seconds. Missed any single variable and the bomb would skip over the ship, detonate short, or sink harmlessly. His orders were chilling. No bomber will attack the same ship twice. This was about maximum efficiency. One pass, one bomb, one chance. The crews filed out at oh-seven-hundred. Fifty-four men and nine B-25s.

Larner climbed into his aircraft. His copilot, Lieutenant Tom Benz, was already running the preflight checklist. The bombardier, Staff Sergeant Carl Walls, was checking the bomb release mechanism for the fourth time. Nobody spoke. This crew had flown together for nine months. They knew what a 50ft approach meant.

They knew the odds. Larner started the port engine, then the starboard. The big Wright Cyclone engines roared to life. His flight would take off first. They would fly low, under 100ft the entire way. Japanese radar at Rabaul couldn’t track aircraft flying that low. Their only advantage. Their only hope was surprise.

At oh-seven-forty-five, Larner released the brakes. By 10:00, he would either be a hero, or he would have led his entire squadron to a slaughter. The flight to the Bismarck Sea took 120 agonizing minutes. Larner held his formation at just 30ft above the ocean. They were so low that spray from the wave tops spattered his windscreen.

Radio silence. The Japanese monitored every frequency one stray transmission and the convoy would know they were coming. Larner checked his watch. Oh-nine-hundred. The convoy should be 60 miles northeast. But flying this low, he couldn’t see more than five miles. His navigation had to be perfect. Five degrees off course, and they would miss the convoy entirely in the empty ocean.

At oh-nine-fifty-five, Larner spotted it. Smoke on the horizon, the black diesel exhaust of 16 ships. He keyed his throat mic. Once. Click the signal to tighten formation. The convoy took shape. Two columns of transports, destroyers forming a protective screen. Larner counted the guns on the nearest destroyer.

Every single one of them would be firing at him in minutes. At 10:00, the first part of the plan began, the Beaufighters. Larner watched as 13 Australian aircraft dove on the convoy. Their cannons raked the destroyer decks. Tracers arced across the water just as planned. The Japanese anti-aircraft guns swung toward the new threat.

The gunners were looking the wrong way. Thirty seconds later, the B-17s arrived. Bombs tumbled from 10,000ft. This was the signal. The Japanese ships began turning hard, breaking formation, scattering. The destroyers accelerated, churning white water. It was perfect chaos. Larner’s voice came over the radio, breaking the silence: Bombers, attack.

He descended to 40ft. Sergeant Walls was calling out the distance. 4000 yards. 3600. Larner picked his target. The second transport in the port. Seven hundred feet long, sitting low in the water, fully loaded. He would aim right where the troop compartments were. The destroyer on the left flank spotted them. Muzzle flashes.

The first shells arced toward his formation. They were high. The Japanese gunners were still thinking high altitude. They hadn’t adjusted yet. 2000 yards. Larner opened fire. All eight 50 caliber guns hammered the ship. Tracers walked across the transport superstructure. Glass shattered. Metal sparked. Men on deck dove for cover.

It was working. The enemy gun crews couldn’t shoot back while 50 caliber rounds were tearing their positions apart. 1200 yards. Larner’s wingmen were spreading out, each bomber lining up on its own ship. Nine bombers attacking nine ships all at once. 800 yards. The destroyer fired again. This time the shells bracketed his plane.

Shrapnel pinged off the fuselage. Benz. The copilot yelled, Hit! Port! Engine oil pressure dropping 600 yards. The transport filled his entire windscreen. A wall of steel rushing toward him. Every instinct in his body screamed, pull up 400 yards! Bomb armed! Ready? 300 yards! Larner hit the release. He felt the B-25 lurch upward as the 1,000 pound bomb dropped free.

He watched it fall. It hit the water, skipped once, and slammed into the transport’s hull. Climb, climb! Larner hauled back on the yoke. The five second fuse was counting down. Five. Four. Three. Two. One. He didn’t see the explosion. He felt the shockwave hit his aircraft like a giant’s fist, throwing the tail up and slamming the plane sideways.

Benz fought the controls. Larner risked a glance back. The transport was splitting in half. A column of black smoke and fire erupted from its middle. Secondary explosions rippled through the deck as ammunition cooked off. The ship was already listing soldiers jumping from the decks. One bomb. 15 seconds. It had worked.

To his right, Jake Faucet’s bomber pulled up. Another transport was burning to his left. Captain Bill Hayes had just hit a destroyer. The bombs skipped and hit the stern. The destroyer’s rear third simply vanished in the explosion. Four targets were hit in the first 90 seconds, but the Japanese were adapting.

A destroyer on the far flank tracked Lieutenant Tom Mitchell’s B-25. The first shell missed. The second missed. The third hit. Mitchell’s aircraft disintegrated. The bomb detonated. The plane vaporized. Five men gone in an instant. Larner saw the debris scatter. No time to mourn. Lieutenant Carl Johnson lined up on the lead.

transport, the convoy flagship. This time the ship was ready. 20 millimeter cannons, machine guns, even rifles fired from the deck. The air was solid with tracers. Johnson held his course. His bomb punched through the hull. The ship erupted in flames. Lieutenant Paul Warren’s bomber took hits. 20mm shells ripped his port wing open.

Fuel streamed out. He held his course at 150 yards. He released a perfect hit. He banked hard right, trailing fire. Six transports were burning. Two destroyers were crippled. One B-25 was lost. The attack had lasted four minutes, and now the second wave of B-25s was coming in. Nine more bombers from the 90th Bomb Squadron.

They had watched Larner’s attack. They knew it worked. They also knew the cost. But this time, the Japanese were ready. Every gun in the convoy was tracking low. The remaining destroyers had formed a defensive line, firing in coordinated volleys. The ocean erupted with shell splashes. The Japanese had learned they would make the Americans pay for the second pass.

Major Ralph Chel, leading the second wave, came in from the east, flying directly out of the sun. It was a smart move. The Japanese gunners were blinded. His bomb hit a transport that was already listing. The ship rolled over and went under in less than two minutes. 1200 soldiers went down with it. Lieutenant Harold Jensen wasn’t as lucky.

His approach was wrong. Too fast. His bomb skipped three times over the destroyer and exploded harmlessly. He pulled up to circle for another run. This was a fatal mistake. The destroyer he’d missed. Tracked him the entire turn. When Jensen came around again, they were waiting. The first shell took off his engine.

The second hit the cockpit. The B-25 rolled inverted and crashed into the sea at 300mph. Eight minutes into the battle, Larner realized with a cold dread that 60 Japanese Zero fighters were still somewhere above the clouds. At oh-nine-fifteen, they appeared. 18 of them diving from 12,000ft. Silver shapes dropping like hawks.

The P-38 Lightning escorts were supposed to keep them busy. Something had gone wrong. Larner’s B-25 was vulnerable. He was low on fuel. He was low on ammunition. His nose guns were nearly empty. He pushed the throttles forward and dove to the wave tops. 20ft, 15ft. His propellers were churning. Salt spray. The Zeros came in fast, 400mph.

Cannons blazing. Tracers arced past Larner’s canopy. He jinked left, then right behind him, his dorsal gunner. Staff Sergeant Tommy Blake fired short bursts. But Lieutenant Warren’s damaged bomber, the one leaking fuel, wasn’t so lucky. A Zero latched on to his tail. Warren tried every maneuver, but the Zero pilot was patient.

He waited until Warren stalled in a climbing turn, then fired a two second burst. Warren’s starboard engine exploded. The bomber nosed over. Larner saw three parachutes. Three out of five. For six minutes, the Zeros pressed their attack. Then suddenly they broke off. Larner saw why the B-17s were coming back for another pass.

The Zeros had to choose. Finish the low level bombers or defend the convoy from the high altitude threat. They chose to defend the convoy. This kind of multi-layered combined arms strategy was what separated a simple raid from a decisive battle. Many of the most fascinating stories from the war involve this kind of tactical genius.

We cover them every week. Larner used the reprieve to check his instruments. Port engine running rough, oil pressure fluctuating fuel 60%. Enough to get home. Maybe. He looked back at the convoy. Eight transports had been hit. Seven were sinking or already gone.

The eighth was burning, trying to beach itself. Four destroyers were damaged. Two dead in the water. The battle of the Bismarck Sea wasn’t over. It was oh-nine-twenty-one. The attack had lasted just 11 minutes, but the killing would continue for three more days. American bombers would return every six hours. P.T.

boats would hunt the survivors in their lifeboats. The Japanese had committed 7000 troops. Fewer than 1200 would ever reach Lae. The rest would drown, burn, or die of exposure. Larner set his course for home Four bombers were confirmed lost 20 men. But the mission the suicide run had worked. This single tactic would be refined, standardized and taught to every bomber squadron in the Pacific.

Within six months, Japanese commanders would abandon all attempts to move large convoys near Allied airpower. The supply line was strangled. The war would turn. But Larner didn’t know that yet. He only knew his fuel gauge was dropping and Port Moresby was 90 minutes away. He ordered his crew to dump everything ammunition, tools, anything to reduce weight.

The B-25 was struggling to stay in the air. At ten-ten, Benz spotted land the southern coast of New Guinea. The port engine was shaking violently, now oil streaming from a crack. The temperature gauge was in the red. Larner feathered the prop, cutting the engine. He transferred all power to the starboard engine.

The bomber slowed to 180mph, just above stall speed. The engine held. He landed at eleven-seventeen. The runway was lined with ground crews. Word had spread. Larner cut the engines and just sat for 30s. His hands still gripping the yoke. The debrief lasted two hours. Five of the nine pilots had returned. Mitchell was gone.

Jensen was gone. Warren’s crew, thankfully, had been picked up by a Catalina flying boat. The reconnaissance photos arrived at thirteen-hundred hours. The images told the story. Eight transports, seven confirmed, sunk. The eighth was beached and burning. Four destroyers, two sunk. Two severely damaged. General Kenney arrived at sixteen-hundred hours.

He didn’t congratulate anyone. He pointed at the reconnaissance photo of the one burning transport still on the beach. He just said, finish it. The second strike launched at seventeen-thirty. By twenty-hundred hours, they were back. The beached transport was gone. The two damaged destroyers were caught trying to withdraw.

Both were sunk. The Japanese started with 16 ships. By nightfall, 14 were on the bottom of the Bismarck Sea. The cost in lives was catastrophic. 7000 Japanese soldiers embarked. Only 900 survivors were counted reaching the shore. American boats intercepted the lifeboats. Command had ordered no quarter. This was a grim reality of the Pacific War.

The Japanese had often machine-gunned American air crews in their parachutes. At Bismarck Sea, the Americans, hardened by months of brutal fighting, returned the favor to soldiers in the lifeboats. Larner learned about it later. He didn’t ask for details. The war had rules until it didn’t. The rules had stopped applying somewhere between Mitchell’s bomber disintegrating and the last Japanese transport going under.

The final numbers were staggering. Japanese losses 12 ships, nearly 6000 men. American losses 13 aircrew killed. Skip bombing had worked, but the question remained would it work against an enemy who was prepared? Three months later, the Japanese tested that question. They formed a new convoy. This time they sailed at night.

This time they had 60 Zeros providing air cover. And this time, every destroyer had new 20 millimeter anti-aircraft guns specifically positioned to defend against low altitude attacks. The Fifth Air Force attacked 12 B-25s. The results were different. Two transports hit. Three B-25s shot down. The exchange rate had shifted.

The Japanese had learned. So the Americans adapted in return. By July, mechanics added more armor around the B-25 cockpits. They increased the forward firing guns to 12 50 calibers. Some B-25s carried 14. The theory remained overwhelm the gunners. On November the 2nd, 1943, 38 B-25s attacked Rabaul Harbor. This time the ships were trapped.

They couldn’t maneuver. The raid lasted 18 minutes. 30 ships were hit. One heavy cruiser sunk. One destroyer sunk. 16 merchant ships damaged or sinking. American losses two B-25s. to skip bombing was devastating against ships trapped in harbor. It was far more dangerous in the open ocean. The statistics tell one story.

Between 1943 and 1945, skip bombing sank 212 Japanese vessels. It was 15 times more effective than high altitude bombing. But the human cost was harder to measure. This tactic required crews to fly steady, straight and low directly at guns that were firing at them. The psychological stress was immense. Pilots who flew skip bombing missions had shorter combat tours and higher rates of combat fatigue.

The tactic worked, but it broke the men who flew it. Major Ed Larner never flew skip bombing again after May 1943. The Army Air Force wanted him to train new crews. He refused. He requested and received a transfer to transport aircraft. He spent the rest of the war flying C-47 moving supplies. No combat, no more watching men.

He’d trained die in aircraft he’d taught them to fly. He never explained the decision. He never had to. Command understood. He declined a promotion to Lieutenant Colonel twice before finally accepting he didn’t want recognition. He just wanted to finish the war and go home. When Ed Larner died in 1993, his obituary mentioned his military service in a single sentence.

It didn’t mention the battle of the Bismarck Sea. It didn’t mention skip bombing. He had asked his family not to discuss it. General Kenney received the official credit in most history books. Larner was fine with that. Kenney had the theory. Larner had just been the one to prove it worked. But the pilots knew the men who flew the missions knew who had led that first attack.

They knew whose techniques kept them alive. When the tracers were filling their windscreens, the battle of the Bismarck Sea is largely forgotten today. It doesn’t have the name recognition of Midway or Guadalcanal, but what remains is this a group of American aircrews that aircraft could sink warships by flying 50ft off the water.

It was called suicide before they proved it worked. It was called genius. Afterward, the truth is, it was desperation meeting innovation. It was men willing to try the impossible because the proven methods were failing. These stories of quiet courage are the ones that move us the most, and they are the ones most often lost to history.

If this story moved you, please drop a comment below and just let us know you were here. Tell us where you’re watching from.

News

CH2 . German Aces Once Mocked the P-51 Mustang as a “Laughable Toy” — Until the Sky Above Berlin Exploded with 209 of Them and Turned Arrogance into Terror…

German Aces Once Mocked the P-51 Mustang as a “Laughable Toy” — Until the Sky Above Berlin Exploded with 209…

CH2 . They Ordered Him to Simply Photograph the Target — Instead He Unleashed a One-Man Assault That Obliterated 40 Japanese Aircraft and Shattered Every Rule of Pacific Air Warfare…

They Ordered Him to Simply Photograph the Target — Instead He Unleashed a One-Man Assault That Obliterated 40 Japanese Aircraft…

CH2 . How One Tail Gunner’s “Recklessly Savage” Counter-Attack Obliterated 12 Bf 109s in Just 4 Minutes — And Force a Brutal Rethink of Air Combat Tactics Forever..?

How One Tail Gunner’s “Recklessly Savage” Counter-Attack Obliterated 12 Bf 109s in Just 4 Minutes — And Force a Brutal…

ch2 . How a Farm Kid’s Forbidden Counter-Tactic Turned a Doomed Air Battle Into a Massacre of German Fighters — And Miraculously Save 300 Bomber Crewmen from Certain De@th??

How a Farm Kid’s Forbidden Counter-Tactic Turned a Doomed Air Battle Into a Massacre of German Fighters — And Miraculously…

ch2 . The Rifle the Army Tried to Erase — Until One Defiant Farm Boy Used It to Hunt Down Nine Japanese Snipers Before Dawn,…

The Rifle the Army Tried to Erase — Until One Defiant Farm Boy Used It to Hunt Down Nine Japanese…

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

End of content

No more pages to load