What Hitler Said When His Generals Told Him Stalingrad Was Lost…?

January 26th, 1943. The Wolf’s lair, East Prussia. Curt Sitesler stood before Hitler’s map table, his uniform hanging looser than it had 3 months earlier. The army chief of staff had lost 26, deliberately eating the same rations as the men trapped in Stalinrad, a silent protest his furer refused to acknowledge.

Now he held a stack of radio messages, each one more desperate than the last. Minefura, Zitesler began, keeping his voice steady. Sixth Army reports they have ammunition for two more days. Medical supplies are exhausted. The men are eating the horses. The horses are gone now. They’re eating leather. The wounded are freezing to death because there’s no fuel for heat.

Hitler’s hand moved across the map, fingers tracing the vulgar river. He didn’t look up. The airlift, Hitler started. The airlift is delivering 100 tons per day, Zitesler interrupted, something he’d never dared before. Sixth Army needs 500 tons minimum to survive. They need 700 tons to have any combat capability.

We’ve never reached even 200 tons in a single day. Hitler’s jaw tightened, but still he stared at the map at the small red circle marking Stalingrad, surrounded by blue Soviet arrows that had closed like a fist 3 months earlier. “Powace must hold,” Hitler said. “I won’t leave the vulgar.” Four months earlier, that same map had shown German forces stretching across the southern Soviet Union in a vast arc of conquest.

Army group south had driven east through the summer, racing toward the oil fields of the Caucuses and the industrial city that bore Stalin’s name. By September, Friedrich Powus’ sixth army had reached Stalingrad, and the battle had devolved into a grinding street by street nightmare that consumed men like fuel.

But they’d been winning. Slowly, building by building, Powus’ men had pushed the Soviets back toward the vulgar. By November, they held 90% of the city. Hitler had declared victory was days away. Then on November 19th, Soviet artillery had opened fire north and south of the city, not at Stalingrad itself, but at the flanks at the Romanian Third Army to the northwest and the Romanian Fourth Army to the south.

Within 4 days, Soviet pins had met at Kalak, 40 mi west of Stalingrad. The trap had closed on 290,000 German and Axis soldiers. Zitesler had been in his position as chief of stealth for barely 2 months when the encirclement happened. He’d immediately requested permission for Sixth Army to break out westward while they still had fuel and ammunition while the Soviet ring was still thin.

Hitler had refused. The Luftwaffer will supply them, Guring had promised, his voice booming with confidence in that first crisis meeting. 500 tons per day minimum. I guarantee it. Wolfrram Fon Richen, the Luftvafa field marshal actually responsible for executing this miracle had gone pale. He’d pulled Sidler aside after the meeting.

It’s impossible, Rishtoven had said, his voice low and urgent. We don’t have enough transport aircraft. The weather is turning. The nearest airfields are too far. Soviet fighters will tear us apart. Tell the furer, Zeites had urged, I did. He won’t listen. Guring promised, so now it must be true. The airlift had begun on November 24th.

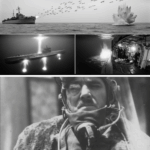

The first day they delivered 75 tons. The second day 50. On some days when blizzards grounded the transports or Soviet fighters prowled the air corridors, nothing got through at all. The Ju52 transports lumbered through flack and fighters and dozens fell burning from the sky. Pilots returned with stories of landing on makeshift air strips under artillery fire, of wounded men crawling toward the planes, of having to choose who to evacuate because there wasn’t room for everyone.

Inside the pocket, 290,000 men had begun to starve. By December, Titler was requesting breakout permission daily. Erish Fon Mannstein had launched a relief operation, Operation Winter Storm, driving towards Stalingrad from the southwest with a Panza army. For 3 days, it had looked like it might work. Mannstein’s tanks had reached within 35 mi of the pocket.

Now, Zeitler had begged, “Order Pow!” to break out now toward Mannstein. It’s the last chance. Hitler had stood at the same map table, staring at Stalingrad. “If we give up Stalingrad, we give up the vulgar. If we give up the vulgar, we give up access to the oil. If we give up the oil, we lose the war. Sixth Army must hold.

Mannstein will reach them.” Mannstein hadn’t reached them. Soviet reinforcements had pushed him back. The relief attempt had failed. The pocket had shrunk as Soviet forces pressed inward. The temperature had dropped to 30° below zero. Men were freezing at their posts, dying in their sleep, too weak from hunger to feel the cold leaving their bodies.

The radio messages had grown shorter and more desperate. Requests for ammunition, for medical supplies, for food, always for food. Then just for permission to surrender the wounded, to let them live. Hitler had forbidden it. Where the German soldier sets foot, there he remains. Now in late January, Zeitler laid the latest reports on the map table.

Soviet forces had split the pocket in two. The southern group was down to a few city blocks. The northern group held a slightly larger area, but barely. Sixth Army headquarters was in the basement of the Uni Vermag department store, surrounded on all sides. Powus reports his men can no longer resist.

Zeitler said they have no ammunition for the artillery. The tanks have been out of fuel for 3 weeks. The men are too weak to hold their rifles steady. He requests permission to no. Hitler said Minefur. They are dying not from combat, from starvation, from cold. There are 30,000 wounded with no medical care.

Gang green is they are tying down Soviet divisions that would otherwise attack elsewhere. Hitler interrupted, finally looking up from the map. His eyes were red rimmed, his face pale. Every day they hold is a day we gain elsewhere. They are fulfilling their duty. They could fulfill their duty better if they broke out weeks ago. Zitler said the words escaping before he could stop them.

They could have saved themselves. They could have saved their equipment. They could be fighting now instead of dying for nothing. Hitler’s hand slammed on the table. It is not for nothing. Stalingrad is a matter of will. If we show weakness, if we retreat, the entire front will collapse. The Sixth Army holds because I order it to hold.

Because Germany requires it. because there is no alternative to victory. Zeitler gathered the reports, his hands shaking, not from fear, from exhaustion, from hunger, from watching 290,000 men die while he stood in a warm room arguing with a man who would not see reality. “How long?” Hitler asked suddenly.

“What? How long can they hold?” Zitesler looked at the latest message received 2 hours earlier. days, perhaps a week, no more.” Hitler nodded slowly. He pulled out a chair and sat, something he rarely did during these conferences. For a moment he looked old, the carefully maintained facade of vigorous leadership cracking. “Powus must not surrender,” Hitler said quietly. “He must fight to the last man.

He must show the Soviets what German soldiers are capable of. He must create a legend that will inspire the army for generations. He’s creating a graveyard, Zitesler said. Hitler stood abruptly. You’re dismissed. 4 days later, on January 30th, Hitler promoted Friedrich Powus to Field Marshall.

The message was sent by radio to the univer where Powus sat wrapped in a blanket, his face gaunt, his hands trembling from cold and exhaustion. The promotion carried an unspoken message that everyone understood. No German field marshal had ever surrendered. The rank was both an honor and a death sentence. Hitler’s way of ordering Powace to commit suicide rather than fall into Soviet hands.

Pace read the message and set it aside. Around him, staff officers lay on the floor, too weak to stand. The basement rireed of unwashed bodies, of infected wounds, of men dying slowly. Outside, Soviet forces were blocks away. The shooting had grown sporadic, not because the Soviets had stopped attacking, but because the Germans had stopped shooting back. There was nothing left to shoot.

On February 1st, Powus sent his final radio message to Hitler’s headquarters. Sixth Army, true to its oath and conscious of the lofty importance of its mission, has held its position to the last man in the last round for Fura and Fatherland unto the end. It was a lie. They hadn’t fought to the last man. They’d run out of ammunition weeks earlier.

But it was the message Hitler wanted, the legend he demanded. The radio fell silent. The next morning, February 2nd, Soviet forces entered the Univer. They found Powus and his staff, barely alive, surrounded by the dead and dying. The field marshal surrendered. Around the pocket, 91,000 German and Axis soldiers emerged from cellers and ruins.

skeletal figures in tattered uniforms, stumbling through snow towards Soviet lines. Most would die in captivity. Only 6,000 would ever see Germany again. The message reached Hitler’s headquarters that afternoon. Titler delivered it, standing at attention, waiting for the explosion. Hitler read the report three times.

His face went white, then red. His hands began to shake. He surrendered, Hitler said, his voice barely a whisper. He surrendered. Then he was shouting, his voice cracking with rage. I gave him a field marshals baton. I gave him the highest honor. He should have shot himself. He should have died with his men. Instead, he surrenders. He goes into captivity.

He’ll be paraded through Moscow like a prize. He’s destroyed everything. The sacrifice, the meaning, all of it destroyed by his cowardice. Hitler paced the room, his movements jerky, uncontrolled. What will the other armies think? What will the soldiers think when they hear their field marshal surrendered? How can I ask anyone to fight to the death when a field marshal chooses captivity? Zitesler said nothing.

There was nothing to say. 290,000 men had been sacrificed for a symbol, for a point on a map, for Hitler’s refusal to accept that his will could not overcome logistics and arithmetic. The Sixth Army was gone. The legend Hitler had wanted of heroic last stands and glorious sacrifice had ended in a basement surrender and columns of starving prisoners.

“This must never happen again,” Hitler said finally, his voice cold now. controlled. No more retreats, no more surrenders. Every position will be held. Every soldier will fight where he stands. If an army is surrounded, it holds. If it runs out of ammunition, it fights with bayonets. If it runs out of food, it fights until it drops. This is what I will demand.

This is what Germany requires. Citizler looked at his furer and understood with perfect clarity that nothing had been learned. The disaster at Stalingrad hadn’t revealed the flaw in Hitler’s thinking. It had reinforced it. In Hitler’s mind, Sixth Army hadn’t failed because they’d been left in an impossible position.

They’d failed because they hadn’t been fanatical enough because Powus had surrendered instead of dying. The lesson Hitler took from Stalinrad wasn’t that armies need supply lines and realistic objectives. It was that willpower had failed, that German soldiers needed to be more ruthless, more willing to die.

The disaster that should have forced a change in strategy had instead hardened Hitler’s determination to never retreat, never surrender, to demand sacrifice without limit or reason. In the months that followed, Hitler would apply this lesson again and again. At Demansk, at Col, at countless other encirclements, he would order armies to hold impossible positions, to fight without supply or reinforcement, to die in place rather than withdraw to defensible lines.

Generals who argued for strategic retreats were dismissed. Officers who suggested saving their men were accused of cowardice. The vermarked would bleed itself white in a series of pointless last stands. Each one justified by Hitler’s conviction that will could overcome material reality. But in February 1943, standing in the wolf’s lair with the reports of Stalingrad’s fall scattered across his desk, Hitler made one more statement that revealed everything about how he understood what had happened.

If Powus had shot himself, Hitler said the sacrifice would have meant something. He would have entered Valhalla. Instead, he chose life and destroyed the meaning of every death that came before his surrender. Zeitler finally spoke. The men didn’t die for meaning, Minefur. They died because we left them there. Hitler’s eyes went cold.

You’re dismissed, Zitler, and you will not speak of this conversation to anyone. Sitler left knowing he’d crossed a line that couldn’t be uncrossed. Within months, he’d suffer a nervous breakdown and be dismissed from his position. But in that moment, walking through the frozen corridors of the Wolf’s lair, he understood something fundamental about the man commanding Germany’s armies.

Hitler hadn’t been shocked when his generals told him Stalingrad was lost. He’d been shocked when Powus surrendered. the loss of the city, the death of 290,000 men, the strategic catastrophe. None of that had shaken Hitler’s faith in his decisions. What shocked him, what enraged him was that his field marshal had chosen survival over the heroic death Hitler had scripted for him.

The tragedy of Stalinrad wasn’t just the battle itself. It was that the battle’s lessons were never learned. Hitler looked at the greatest military disaster in German history and concluded that the problem was insufficient fanaticism. He saw 290,000 dead and decided the mistake was that 91,000 had lived.

The generals had told him Stalingrad was lost in late January when the situation was clearly hopeless. Hitler had refused to believe it until February 2nd when the surrender made denial impossible. But even then, even with the evidence undeniable, Hitler didn’t accept that Stalingrad was lost because of his decisions.

He accepted only that Powace had failed him, that the soldiers hadn’t been willing enough to die, that next time he would demand even more. This was Hitler’s response when his generals told him Stalingrad was lost. Denial, rage, and a determination to repeat the same mistakes on an even larger scale. The city on the vulgar had consumed an army.

Hitler’s response to that consumption would be to feed more armies into more hopeless battles, each time expecting that sufficient will would produce different results. In the basement of the Univag department store, Pace had chosen life. In the wolf’s lair, Hitler had chosen to learn nothing. Of the two decisions, history would judge Hitler as the greater betrayal, not of military strategy or tactical sense, but of the hundreds of thousands of men who would die in the years ahead because their supreme commander valued

symbolic gestures over their lives. The map on Hitler’s table still showed Stalingrad as a German position for three more days after the surrender. No one had updated it. The red circle remained, a fiction on paper, a refusal to acknowledge reality that perfectly captured Hitler’s response to the disaster.

When finally someone changed the map, replacing the German marker with a Soviet one, Hitler had left the room. He couldn’t bear to watch the symbol of his will erased from the chart. That was what Hitler said and didn’t say when his generals told him Stalingrad was lost. He said they must hold. He said they must fight to the last man.

He said retreat was impossible. Surrender was unthinkable. Death was preferable to defeat. And when defeat came anyway, when the last man didn’t die, but surrendered instead, Hitler said it was Powus’s failure, not his own. The generals had tried to tell him the truth in November, in December, in January.

They’d presented the numbers, the logistics, the impossible arithmetic of supplying an army by air through winter storms. They’d begged for permission to break out, to save what could be saved. Each time Hitler had refused, had insisted on holding, had promised that Will would overcome reality. When they finally told him it was over, that Stalingrad was lost beyond any possibility of recovery, Hitler’s response wasn’t acceptance or regret.

It was fury that his orders hadn’t been obeyed unto death, that his field marshal had chosen captivity over suicide, that the ending he’d scripted hadn’t been performed. The generals left those meetings understanding that nothing they said would change Hitler’s mind, that no disaster would teach him caution, that the next encirclement would be handled exactly like Stalingrad, with demands to hold at all costs and refusals to authorize retreat until it was too late. They were right.

The pattern would repeat at Corsun, at Churkasi, at Budapest, at Kernigburg, at Berlin itself. Each time Hitler would order armies to hold impossible positions. Each time generals would try to explain why this was suicide. Each time, Hitler would respond the same way he’d responded about Stalingrad. Hold, fight, die if necessary. Never retreat.

What Hitler said when his generals told him Stalingrad was lost was everything and nothing. Everything because his words revealed his complete inability to accept reality or learn from catastrophe. Nothing because no words could undo the decisions that had already doomed Sixth Army.

And because the words he spoke changed nothing about how he would command in the future. The city on the vulgar had fallen. 290,000 men were dead or captured. The Eastern front had been torn open. Germany’s aura of invincibility had been shattered. And Hitler’s response was to demand that next time everyone die more enthusiastically. That was the true horror of what Hitler said when his generals told him Stalingrad was lost.

Not the specific words, but what the words revealed. that he had learned nothing, would learn nothing, and would send hundreds of thousands more men to die in the same feutal way for the same impossible reasons, while refusing to acknowledge that the fault was his

News

CH2. What Hitler Said When British Bombers Reached His Eagles Nest…? April 25th, 1945. Squadron leader Tony Ives pushed his Lancaster bomber through the morning sky over Bavaria. The Alps rising ahead like jagged teeth.

What Hitler Said When British Bombers Reached His Eagles Nest…? April 25th, 1945. Squadron leader Tony Ives pushed his Lancaster…

ch2 . What Hitler Said When German Civilians Begged Him to End the War… February 1945, Joseph Gerbles sat at his desk in the propaganda ministry reading the latest Sicker Heights Deanst report on civilian morale. His hand trembled slightly as he turned the pages. The intelligence services agents had been thorough, perhaps too thorough.

What Hitler Said When German Civilians Begged Him to End the War… February 1945, Joseph Gerbles sat at his desk…

My Sister Got Pregnant with My Fiancé, and My Family Chose Her Over Me—So I Made Them All Pay in the Cruelest Way They Could Ever Imagine…

My Sister Got Pregnant with My Fiancé, and My Family Chose Her Over Me—So I Made Them All Pay in…

“You Gave Me Tuition? Now Give Me 40% of Every Paycheck I’ll Ever Earn!”—The Day My Parents Turned My Life Into a Prison Without Bars…

“You Gave Me Tuition? Now Give Me 40% of Every Paycheck I’ll Ever Earn!”—The Day My Parents Turned My Life…

At My 19th Birthday, Dad Threw $10 at Me; I Gave Him an Envelope, and When He Looked Out the Window, He Turned Ghostly Pale as the Past He Tried to Bury Walked Right onto Our Porch…

At My 19th Birthday, Dad Threw $10 at Me; I Gave Him an Envelope, and When He Looked Out the…

The Day My Stepfather Tried to Bury My Future Alive — and the Moment a Single Forbidden Document Dragged His Darkness Into the Light Before He Even Realized I Was Already Watching Him Bleed From His Own Lies…

The Day My Stepfather Tried to Bury My Future Alive — and the Moment a Single Forbidden Document Dragged His…

End of content

No more pages to load