US Pilots Examined A Captured Betty Bomber — Couldn’t Understand Why It Had Unprotected Fuel Tanks…

January 31, 1945. The heat over Clark Air Base shimmered in waves, rising from the concrete like the exhale of some enormous engine. Major Frank T. McCoy stepped toward the aircraft sitting alone on the tarmac, his boots grinding against the dust blown in from the surrounding fields. He had inspected wrecked Zeros, charred Oscars, even shattered bombers before, but nothing like this. This machine was whole, untouched, waiting in the sunlight as if its crew had simply vanished. The tail markings read 763-12 — a Mitsubishi G4M, known to every American pilot by its notorious nickname: the “Betty.”

McCoy raised his camera, but his hands were not steady. The bomber’s fuselage glinted like polished metal, long and cylindrical, the famous tubular body that Allied pilots swore burned like dry timber when hit. Nearly twenty meters from nose to tail, it sat balanced on its tricycle landing gear like some oversized silver cigar left on the runway. The wings stretched twenty-five meters from tip to tip, unscarred, their smooth surfaces revealing not a single bullet hole or scorch mark. Even the engines — two massive fourteen-cylinder radials, each capable of producing more than a thousand horsepower — looked ready to start with a simple flick of the magneto switch.

This was not the mangled remains of an aircraft dragged off a battlefield. This was a fully operational bomber, abandoned by its crew as the American advance swept across Luzon. And inside it, McCoy expected to find the standard safeguards any bomber of such range and power required. But when he climbed into the wing root and opened the inspection panels, he froze.

There was nothing. No self-sealing rubber. No protective layering. No armored plating shielding the fuel bays. No fire suppression lines. Only thin sheets of aluminum — barely two millimeters thick — separating thousands of liters of high-octane gasoline from any enemy round that happened to strike the wing. It was, by American standards, unthinkable.

Major McCoy commanded the Technical Air Intelligence Unit in the Southwest Pacific. He had dissected Japanese aircraft across dozens of islands, gathering fragments of wings and engines to understand the enemy’s capabilities. But standing inside the Betty’s wing, tracing his hand along the bare metal walls of the fuel tank, he realized he had never seen anything so vulnerable. The design philosophy behind this bomber was not simply unfamiliar — it was alien. The Americans had believed the Japanese valued maneuverability. They had not realized how far Japanese engineers were willing to cut protection to achieve range.

The implications would take months to unravel. Every assumption about Japanese doctrine, about what risks their designers found acceptable, about how the Imperial military weighed crew survival against operational range, collapsed in front of him. And yet the story of this aircraft, this revelation, did not begin on the tarmac at Clark. It had begun four years earlier, on December 8th, 1941. As smoke still rose from Pearl Harbor, eighty-two G4M bombers and twenty-six G3Ms lifted off from Formosa. Their target was Clark Field itself, the heart of American air power in the Philippines. The attack achieved complete tactical surprise.

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

January 31, 1945. Clark Air Base, Luzon, Philippines. Major Frank T. McCoyy’s hands trembled slightly as he photographed the aircraft before him, an intact Mitsubishi G4M Betty bomber bearing the tail number 763-12. This cannot be their standard design. No air force would build bombers this way. The fuselage gleamed in the tropical sun, its distinctive cylindrical shape justifying its Allied nickname.

Measuring nearly 20 m from nose to tail, the bomber sat on its tricycle landing gear like a massive cigar resting on the tarmac. The wings, spanning 25 m tip to tip, showed no battle damage. The engines, 14 cylinder radials producing,500 horsepower each, appeared intact. This was not a crashed aircraft salvaged from wreckage.

This was a complete operational bomber abandoned by its crew during the American advance. But what had captured McCoy’s complete attention, what would revolutionize American understanding of Japanese aviation doctrine was what he discovered when he climbed inside the wings through the inspection panels. The fuel tanks were completely unprotected. No self-sealing rubber compound, no armor plating, no fire suppression systems, no protective coatings of any kind, just thin aluminum skin, perhaps 2 mm thick, separating thousands of liters of high octane aviation fuel from enemy machine gun fire. Major McCoy, commander of the

technical air intelligence unit Southwest Pacific, had examined dozens of crashed Japanese aircraft across the Pacific. But nothing had prepared him for this moment. This bomber, abandoned intact during the American liberation of Clark Field, would expose a design philosophy so alien to Western military thinking that it would take months for analysts to fully comprehend its implications.

The mathematics of this discovery would reshape American tactical doctrine and aircraft design for the remainder of the war. Every assumption American pilots held about enemy capabilities, about the price Japanese engineers were willing to pay for performance, about the value Imperial forces placed on crew survival, was about to be systematically demolished by the evidence contained within this single pristine example of Japan’s most important bomber.

The journey to this revelation had begun 4 years earlier on December 8th, 1941. That morning, as smoke still rose from Pearl Harbor, 82 G4M bombers and 26 G3M bombers lifted off from bases on Formosa. Their target was Clarkfield itself, the primary American air base in the Philippines. The attack achieved complete tactical surprise.

Arriving at 12:35 in the afternoon, the Japanese formation flew at 20,000 ft beyond the reach of American anti-aircraft guns. 27 bombers from the initial wave dropped 636 bombs across Clarkfield’s runways and facilities. Moments later, zero fighters swept in at treetop level, their machine guns, destroying every aircraft that had survived the bombing run. Of 17B17 flying fortresses on the ground, 12 were destroyed outright.

Nearly every P40 Warhawk fighter was reduced to burning wreckage. In 45 minutes, American air power in the Philippines had been effectively eliminated. Lieutenant James Harrington, one of the few surviving American pilots, watched from a bomb shelter as the Japanese formation withdrew to the north. What struck me was how they came in, he later wrote in his combat report.

Perfect formation, high altitude, totally beyond our reach. Then the fighters dropped down and tore us apart. We couldn’t get a single plane airborne, but the Betty bombers themselves had departed untouched. The few American fighters that managed to get airborne arrived too late, finding only empty sky.

The Japanese had demonstrated their bombers’s exceptional range, striking from bases 460 mi away, a feat no American bomber could match at that stage of the war. The Betty’s first year of combat would prove devastatingly effective. On December 10th, 1941, just 2 days after the Clarkfield raid, 26 G4M bombers joined with older G3M Nell bombers in attacking Force Z.

a British naval task force built around the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser HMS Repulse. The attack began at approximately 12:20 in the afternoon. Japanese bombers approached in coordinated waves, their torpedo runs executed with precision that stunned British observers. The Betty bombers carried Type 91 aerial torpedoes, each weighing 840 kg with a 205 kg warhead.

The torpedoes were designed specifically for shallow water operations, running at depths that could strike ships even in coastal waters. The torpedo attacks focused on the two capital ships with devastating accuracy. Prince of Wales, a battleship displacing 43,000 tons and representing the newest generation of British naval power, took at least six torpedo hits along with damage from level bombers.

The underwater explosions ripped massive holes in the ship’s hull, flooding overwhelmed damage control efforts. The battleship began listing severely. Repulse, a battle cruiser built during World War I, but modernized in the 1930s, absorbed at least four torpedo hits while attempting to evade the attacking aircraft.

The ship’s anti-aircraft fire claimed several Japanese aircraft, but could not prevent the coordinated torpedo runs from finding their targets. The cumulative damage proved fatal. Both capital ships capsized and sank within hours of the attack. Prince of Wales went down at approximately 1320 hours. Repulse followed at approximately 1333 hours. 841 British sailors died. The survivors were rescued by escorting a destroyers.

The engagement lasted less than 2 hours from first contact to final sinking. For the first time in naval history, capital ships actively defending themselves had been sunk solely by air power while in the open sea. The G4M Betty bomber had achieved what naval theorists had debated for decades.

British naval superiority in Asian waters had been shattered in 90 minutes. Across the Pacific theater through early 1942, American and Allied pilots encountered Betty bombers in every major engagement. The aircraft seemed to operate with impunity, striking targets at ranges that defied conventional understanding. They hit Darwin, Australia from bases 1500 m away, demonstrating reach that exceeded any Allied bombers capability.

They attacked Port Moresby from airfields across New Guiney’s mountain ranges, maintaining pressure on Allied positions throughout the Southwest Pacific. They struck Guadal Canal from Rabal, a distance exceeding 600 m, projecting Japanese air power across vast ocean expanses. The Betty’s operational range gave Japanese forces strategic flexibility that Allied commanders struggled to counter.

American fighters based at forward positions lacked the range to intercept Betty bombers departing from distant bases. Allied airfields came under attack from Japanese bases that were themselves beyond Allied striking range. The asymmetry in bomber capability meant that Japanese forces could attack at will while Allied forces struggled to retaliate effectively.

This advantage persisted through the first 6 months of the war. Betty bombers participated in virtually every Japanese offensive operation across the Pacific and Southeast Asia. They struck targets in the Philippines, Malaya, Netherlands, East Indies, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. They supported naval operations throughout the theater.

They performed reconnaissance missions that exceeded the range of any Allied aircraft. The Betty became the symbol of Japanese air power’s reach and effectiveness. But the advantage depended entirely on limited allied fighter opposition. When Betty formations could strike without interception, when they could approach targets at high altitude beyond anti-aircraft range, when they could deliver weapons and depart before fighters arrived, the aircraft was devastatingly effective. These conditions characterized operations during the first half of 1942 when

Allied air strength remained limited and dispersed. But by mid 1942, the tactical picture began to change. As American fighter strength increased as wildats gave way to more capable Hellcats and Corsaires, as pilot training improved and tactical doctrine evolved, Betty Crews began reporting disturbing losses.

The shift became undeniable on August 8th, 1942. 23 G4M bombers from the fourth air group departed Rabol to attack American positions at Guadal Canal. American fighters intercepted the formation over Tsavo Island. In the engagement that followed, 18 of the 23 Betty bombers were shot down.

Approximately 120 aviators died in what would become the single worst G4M loss during the entire campaign. Fighter pilots reported the same observation across every engagement. The Betty exploded into flames with minimal hits. Two or three rounds anywhere along the fuselage or wings produced catastrophic results. The aircraft earned grim nicknames that spread rapidly through American squadrons.

Flying cigar, oneot lighter, flying Zippo. all references to the Betty’s terrifying tendency to bloom into fire from battle damage. By October 1942, when Lieutenant Commander John Thomas Blackburn arrived at Guadal Canal commanding VF17 flying F4U Corsair’s, the Betty’s reputation had transformed completely.

First time we caught a Betty formation, we couldn’t believe how easy they went down. Blackburn later reported, “Hit them anywhere along the fuselage or wings and they’d explode. We actively hunted them, recognizing them as among the most vulnerable targets in Pacific skies. But the true extent of the Betty’s vulnerability, the engineering decisions that made such catastrophic losses inevitable, would not be fully understood until American forces began capturing intact examples for detailed examination.

The first significant intelligence breakthrough came in November 1942 when Australian forces overran Japanese airfields at Buna in Papa Newu Guinea. Among the abandoned aircraft, technical air intelligence units discovered Betty bombers with varying levels of damage. Initial examinations confirmed what pilots had reported. The fuel tanks had no protection whatsoever.

Aeronautical engineers with the Allied Technical Air Intelligence Unit, Southwest Pacific, conducted the first detailed analysis. The wing access panels revealed fuel cells with no protective measures, thin aluminum construction, no rubber sealant layer, no protective coating, no fire suppression systems.

Multiple Betty bombers examined at Buuna showed identical characteristics. This was not battle damage or field modification. This was standard Japanese design. The implications were staggering. American bombers by 1942 universally featured self-sealing fuel tanks. The B7 Flying Fortress had incorporated them from the B17C model onward.

The B-24 Liberator had featured them from the XB24B prototype. Even fighter aircraft like the P38 and P47 featured protected fuel systems. Self-sealing fuel tanks used layered rubber compound that swelled on contact with fuel when punctured by bullets or shell fragments, sealing holes and preventing fuel loss and fire.

The technology added substantial weight to aircraft, but dramatically improved crew survival rates. American military doctrine considered this weight penalty essential and non-negotiable. Yet here was Japan’s primary land-based bomber produced in thousands, operating across the entire Pacific theater with fuel tanks that offered zero protection.

The weight saved by eliminating self-sealing systems, armor plating, and fire suppression equipment was immediately apparent. But the cost in crew lives becoming equally obvious in loss statistics that mounted with every engagement. The captured Betty at Clark Field in January 1945 would provide the most complete technical analysis.

Major McCoy and his team spent three weeks dismantling and documenting every system. Their report classified secret and distributed to all Allied air forces, detailed specifications that explained both the Betty’s extraordinary capabilities and its catastrophic vulnerabilities. The G4M model 1 specifications revealed an aircraft optimized ruthlessly for range and speed.

Empty weight of 6,741 kg. Remarkably light for a bomber of its size. Maximum takeoff weight of 9,500 kg. Fuel capacity of 4,780 L distributed across eight unprotected tanks, four in each wing, positioned in the wings center section where they were most vulnerable to combat damage. Top speed of 428 km perph or approximately 265 mph.

Maximum range of 6,34 km exceeding 3,700 m. Service ceiling of 8,500 m. crew complement of seven members including pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier, radio operator, and two gunners. The fuel system design was particularly revealing. The eight tanks were arranged in four groups of two positioned along the wing’s longitudinal axis where the wing joined the fuselage.

This placement maximized fuel capacity by utilizing the thickest portion of the wing structure, but it also positioned the tanks directly in the path of enemy fire during combat. Any attack from the side or below would inevitably strike fuel tanks. The aluminum construction provided no protection. The absence of self-sealing compounds meant that even small punctures would leak fuel continuously.

American engineers calculated that the weight saved by eliminating protection systems exceeded 500 kg per aircraft. This weight savings translated directly into additional fuel capacity and extended range. But the cost invulnerability was equally calculable. Combat reports showed that Betty bombers hit anywhere in the wing area exploded with near certainty.

The unprotected tanks created what engineers termed a critical failure point. a single system whose destruction guaranteed loss of the entire aircraft. These numbers told the story of design choices made in September 1937 when the Japanese Navy issued requirements that would define the G4M’s entire existence.

Top speed of 398 kmh. Cruising altitude of 3,000 m. range of 4,722 km unloaded or 3,700 km carrying 800 kg of bombs or torpedoes. The requirements reflected Japanese naval strategy in the late 1930s. Japan’s empire stretched across vast Pacific distances. Naval bases were separated by thousands of kilometers of ocean.

The Navy needed bombers capable of striking enemy positions far beyond the range of carrier aircraft. bombers that could operate from land bases to support naval operations across the entire theater. Existing Japanese bombers fell far short of these requirements. The G3 Mell bomber, then in service, had a maximum range of approximately 3,000 kilometers. American bombers like the B7 had even more limited range in their early variants.

No bomber in service anywhere in the world in 1930. seven could strike targets at the distances Japanese planners envisioned. The Navy’s requirements were not arbitrary. They were calculated based on the distances Japanese forces would need to cover in any future Pacific conflict. From Formosa to the Philippines, 460 mi. From Rabol to Guadal Canal, 600 m.

From Japanese home islands to potential targets across the Pacific, thousands of miles. The bomber that could meet these requirements would give Japan strategic reach that no other nation possessed. But the requirements also reflected assumptions about future warfare that would prove catastrophically wrong.

Japanese planners assumed that surprise and initiative would provide protection for long-range bombers. They assumed that enemy fighter opposition would be limited by range and numbers. They assumed that the war would be decided quickly before enemy industrial capacity could generate overwhelming force.

Every assumption would prove false. The man tasked with achieving the impossible was Kiro Honjo, who led the Mitsubishi design team after taking over from Joji Hattorii. Honjo had studied bomber design at Junkers in Germany during the early 1930s, absorbing European aeronautical engineering principles and manufacturing techniques before returning to Japan.

He understood immediately that meeting the Navy’s requirements would demand compromises that Western air forces would never accept. Honjo assembled a team of engineers at Mitsubishi’s Nagoya facilities to tackle the design challenges. The team analyzed every aspect of bomber design, calculating weight budgets for every component and system.

They studied existing bombers from multiple nations, identifying where weight could be reduced without compromising structural integrity. They experimented with new construction techniques and materials that might offer weight savings. The mathematics were brutally simple. To achieve the required range, the aircraft needed massive fuel capacity. Each liter of aviation fuel weighed approximately 0.8 kg.

4,780 L of fuel meant approximately 3,800 kg of fuel weight at full load. To achieve the required speed with this fuel load, the aircraft needed minimal weight. Every kilogram added to the empty weight reduced either range or payload capacity. These two requirements existed in direct opposition. Fuel was heavy.

Protection systems were heavy. Armor plating weighing hundreds of kilg would be required to protect crew positions and vital systems. Self-sealing fuel tanks added substantial weight through the rubber compounds and additional structure required. Fire suppression systems added weight. Redundant safety measures added weight.

The cumulative weight of adequate protection would prevent achieving the required performance. Honjo made the decision that would define the G4M throughout its service life. Protection would be sacrificed for performance. The fuel tanks would be unprotected aluminum construction, no self-sealing compounds, no armor plating around fuel cells, no fire suppression systems beyond basic fire extinguishers, no redundant safety measures.

Every kilogram saved would be invested in fuel capacity, range, and achieving the Navy’s performance specifications. The decision was not made lightly. Honjo understood the risks. His team calculated the vulnerabilities that unprotected fuel tanks would create. They knew that combat damage to the wings would likely prove catastrophic, but they also knew that the Navy’s requirements could not be met any other way with available technology.

The choice was between an aircraft that met performance specifications with known vulnerabilities or an aircraft that failed to meet requirements but offered better protection. The Navy had demanded performance. Honjo delivered performance. The first G4M prototype flew on October 23rd, 1939. The aircraft met every performance requirement the Navy had specified. Speed exceeded expectations.

Range surpassed projections. Payload capacity satisfied operational needs. The bomber entered production as the Navy type 1 attack bomber with Mitsubishi building the aircraft at plants in Nagoya. Initial production models designated G4M model 1 began reaching operational units in April 1941.

By December 1941, approximately 180 G4 Miz were in service with the Japanese Navy. These aircraft would form the backbone of Japanese land-based air power throughout the Pacific War. The Betty’s combat debut at Clark Field and against Force C demonstrated the wisdom of Honjo’s design priorities in the specific conditions of early 1942. When facing limited opposition, when achieving surprise, when operating beyond the range of enemy fighters, the Betty was devastatingly effective.

Its range allowed strikes from bases that enemies considered safe. Its speed permitted rapid penetration of target areas. Its payload delivered meaningful damage. But these advantages depended entirely on the assumption that Betty formations would face minimal opposition.

The moment American fighter strength increased, the moment interception became routine, the moment sustained combat became inevitable, every design choice that prioritized range over protection became a death sentence for crews. The Guadal Canal campaign exposed the fundamental flaw in the Betty’s design philosophy. From August through October 1942, more than 100 G4M bombers were lost with their crews in what became a sustained bloodletting that Japanese air forces could not sustain.

The single mission on August 8th alone destroyed 18 of 23 aircraft with approximately 120 aviators killed. The pattern repeated with brutal consistency throughout the campaign. Betty formations would depart from Rabal, fly 600 m to Guadal Canal, engage American fighters, and suffer catastrophic losses. August 9th saw additional bombers lost. August 10th brought more losses.

By the end of August, the fourth air group had been effectively destroyed as an operational unit. September brought no restbite. Betty formations continued striking American positions at Guadal Canal and American fighters continued destroying them in overwhelming numbers. The mathematics were inexurable. Japanese forces needed to strike American positions to contest control of the island.

Betty bombers provided the only means of delivering meaningful strike capability from Rabol. But every mission resulted in losses that could not be replaced. October saw the pattern continue. American fighter strength increased as more squadrons arrived at Henderson Field. Pilot quality improved as combat experience accumulated. Tactical doctrine evolved to exploit Betty vulnerabilities more effectively.

Japanese losses accelerated even as the number of bombers available for missions declined. By November, when the Guadal Canal campaign effectively ended with Japanese withdrawal, Betty losses exceeded 100 aircraft. Crew casualties approached 700 men dead. The exchange rate was unsustainable. Japan’s most capable land-based bomber had been rendered obsolete by its own vulnerabilities, transformed from a feared weapon into what American pilots called easy meat. Japanese planners had expected losses.

All military operations involved casualties, but the scale of Betty losses exceeded every projection. The unprotected fuel tanks that permitted 6,000 km range also guaranteed that any hit to wings or fuselage would likely prove fatal. There was no middle ground, no wounded bombers limping home, no damaged but survivable aircraft.

Betty bombers either returned untouched or exploded in flames. By mid 1943, Japanese engineers recognized that modifications were essential. Starting with the 663rd aircraft produced in March 1943, 30 mm rubber sheets were installed beneath wing surfaces where fuel tanks were located. These sheets were not true self-sealing tanks.

They were a compromise measure, adding minimal weight while providing limited protection against fuel leakage. The modification reduced top speed by 9 km per hour. Maximum range decreased by 315 km, but crew survival rates showed no significant improvement. The rubber sheets could slow fuel leakage from small caliber hits.

They could not prevent fires from larger caliber rounds or cannon shells. They could not stop explosions when tracers ignited fuel vapor. The fundamental vulnerability remained unchanged. Japanese designers attempted more comprehensive protection with the G4M Model 3 introduced in October 1944. This variant featured actual self-sealing fuel tanks with capacity reduced to 4,490 L to accommodate the leak blocking material.

The modification reduced maximum range to 3,640 km, a loss of more than 2,000 km compared to the original G4M model 1. Approximately 60 G4M Model 3 aircraft were produced by war’s end. The modification came too late and in too limited numbers to affect the Betty’s combat record. By late 1944, American air superiority was so complete that no level of fuel tank protection would have permitted Betty bombers to operate effectively. The war’s outcome had already been determined.

The Betty’s vulnerability became so notorious that American forces began using the aircraft in ways that highlighted the dangers Japanese crews faced. On April 18th, 1943, the Betty bomber became the instrument of Admiral Isizuroku Yamamoto’s death in an engagement that demonstrated both American signals intelligence capabilities and the aircraft’s fatal weaknesses.

American codereers intercepted Japanese communications indicating that Yamamoto would fly from Rabal to Bugenville on April 18th. The admiral would travel aboard a G4M bomber with a fighter escort. 18 P38 Lightnings from the 339th Fighter Squadron were assigned to intercept the flight, though only 16 actually flew the mission after one aircraft blew a tire on takeoff and another suffered drop tank failures.

The mission required extraordinary precision. The P38s would fly over 400 m at wavetop height to avoid radar detection, navigate across open ocean without landmarks, and arrive at exactly the calculated intercept point at exactly the calculated time. Any error in navigation, any deviation in timing would result in mission failure.

The intercept had to occur within a narrow window when Yamamoto’s aircraft would be vulnerable. The P38s departed Guadal Canal at 0725 hours. They flew at 50 ft above the ocean for over 400 m, maintaining strict radio silence. Navigation was by dead reckoning and timing. The formation arrived at the calculated intercept point with precision that would become legendary in aviation history.

At 0934 hours, exactly on schedule and exactly 1 minute ahead of the calculated intercept time, the P38 spotted Yamamoto’s formation. Two Betty bombers flying at low altitude with six zero fighters as escort. Captain Thomas Lanir and First Lieutenant Rex Barber broke from the formation to engage the bombers while other P38s held off the zero fighters.

Barber engaged the lead Betty bomber which carried Admiral Yamamoto. The bomber took hits to the wing area where the unprotected fuel tanks were located. The aircraft exploded in flames and crashed in the jungle. Yamamoto’s body was recovered. The Toma following day he had been killed by injuries sustained during the crash. The second Betty bomber also crashed, killing all aboard.

The operation demonstrated multiple aspects of Allied superiority. American signals intelligence had intercepted and decoded Japanese communications. American planning had calculated intercept timing with 1 minute precision over 400 m of ocean. American fighters had executed the mission flawlessly despite extraordinary navigation challenges.

And the Betty bombers vulnerabilities had guaranteed that successful interception would be fatal. There was no possibility of Yamamoto’s bomber surviving once it came under attack. The unprotected fuel tanks ensured that any damage would be catastrophic. The Betty’s vulnerability reached its most dramatic demonstration on March 21st, 1945. 18 G4M bombers took off from Koya Air Base, each carrying an MXY7 Ochre rocket bomb beneath its fuselage.

The Ochre was a piloted rocket powered aircraft with a 1,200 kg warhead designed for kamicazi attacks against American ships. The mission required the Betty bombers to fly within 20 km of their targets before releasing the Ochre aircraft. The Ochre pilot would then ignite the rocket motor and dive at speeds exceeding 650 km per hour toward American ships.

The warhead’s 1,200 kg of explosives would destroy any vessel it struck, but the mission depended entirely on the Betty bombers surviving long enough to reach release range. The formation departed Canoya at approximately 1430 hours. The 18 G4M bombers flew in tight formation with fighter escort heading toward American naval forces off Okinawa.

Each bomber carried an ochre weapon beneath its fuselage, adding substantial weight and drag that reduced speed and maneuverability. The bombers were even more vulnerable than usual, unable to evade or maneuver effectively while carrying the ochre loads. American radar detected the formation at approximately 100 m distance. F6 F Hellcat fighters from USS Hornet were scrambled to intercept.

The Hellcats reached the Japanese formation well before it approached release range for the ochre weapons. In the engagement that followed, American fighters systematically destroyed the entire formation. The Betty bombers, already vulnerable under normal circumstances, proved completely helpless while carrying ochre weapons.

The additional weight prevented evasive maneuvers. The external weapon created drag that reduced speed. The unprotected fuel tanks guaranteed that any hit would be fatal. One by one, the bombers exploded and fell into the ocean. Not a single Betty bomber survived to reach release range. Not a single ochre weapon was launched against American ships.

137 bomber crew members and 15 ochre pilots died in the attack. The mission represented the ultimate expression of the Betty’s fundamental flaw. An aircraft designed to deliver weapons to distant targets could not survive to deliver those weapons when facing prepared opposition.

The extraordinary range that made the mission theoretically possible meant nothing when the aircraft exploded before reaching weapon release range. The final mission flown by Betty bombers came on August 19th, 1945, 4 days after Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender. Two white-painted G4M bombers with green crosses departed at Sugi airfield carrying Japanese representatives to discuss surrender terms with Allied forces.

The aircraft given call signs Baton 1 and Baton 2 flew to Eosima where the Japanese delegation transferred to an American C-54 for transport to Manila. The symbolism was profound and deliberate. The white paint and green crosses indicated peaceful intent, transforming the bombers from weapons of war into vehicles of diplomacy.

The call signs Baton 1 and Baton 2 referenced the location where American forces had surrendered to Japan in April 1942, one of the most devastating defeats in American military history. Now, 3 years later, aircraft bearing those call signs carried Japan’s surrender delegation. Lieutenant Den Sudo piloted one of the surrender aircraft, a G6M model 1 transport variant converted from the bomber airframe.

The transport variants retained the Betty’s distinctive cylindrical fuselage and wing configuration, but carried passengers and cargo rather than weapons. The crew wore dress uniforms rather than flight suits. The aircraft carried no weapons, no ammunition, no military equipment of any kind beyond what was necessary for flight. The flight from Atsugi to Eashima covered approximately 1,000 km, well within the Betty’s range, even in transport configuration.

American fighters escorted the White Betty bombers throughout their flight, ensuring they remained on the prescribed course. The escort was both protective and supervisory, guaranteeing safe passage while preventing any deviation from planned routes. The white Betty bombers with green crosses became the final image of the aircraft that had opened the Pacific War at Clark Field in December 1941.

The circle was complete. The bomber that had destroyed American air power in the Philippines in the war’s first hours now carried Japan’s surrender delegation in the war’s final days. The aircraft that had symbolized Japanese air powers reach and effectiveness now symbolized Japan’s defeat and submission to Allied terms.

The Betty’s production statistics reflect both the aircraft’s importance to Japanese operations and the terrible cost of its design philosophy. Total production reached approximately 2,414 aircraft across all variants, though some sources site figures as high as 2,435 when including all prototypes and subtypes.

The variation in total numbers reflects different methods of counting prototypes, subtypes, and transport variants. The G4M model 1 comprised approximately 1,172 aircraft produced from 1941 through early 1943. This variant featured the original unprotected fuel tank design with capacity of 4,780 L. Top speed reached 428 km per hour. Maximum range of 6,034 km made it the longest ranged bomber in service anywhere in the world.

But the complete absence of protection systems made it catastrophically vulnerable once American fighter strength increased. The G4M model 2 with increased fuel capacity and slightly higher speed accounted for approximately 1,142 examples produced from 1943 through 1945. This variant increased fuel capacity to 6,490 L, extending maximum range even further. Top speed increased slightly to 437 kmph, but the model 2 retained the fundamental vulnerability of unprotected fuel tanks.

The modifications improved performance without addressing survivability. The G4M model 3 designated model 34 represented the only variant with actual self-sealing fuel tanks. Production began in October 1944, but only 60 to 91 aircraft were completed by wars end depending on source. The self-sealing tanks reduced fuel capacity to 4,490 L to accommodate the leak blocking material.

Maximum range decreased to 3,640 km, a loss of more than 2,000 km compared to the model 1. The modification came too late and in too limited numbers to affect combat outcomes. The G6M transport variant converted from bomber airframes added another 30 aircraft. These transport versions carried passengers and cargo rather than weapons serving in liaison and communications roles.

The G6M model 1 used for one of the surrender aircraft in August 1945 represented this variant. Production continued through August 1945 with final aircraft completed just days before Japan’s surrender. Mitsubishi factories produced Betty bombers at peak rates of approximately 100 aircraft per month during 1943. Production decreased in 1944 and 1945 as Allied bombing disrupted Japanese industry and as resources were diverted to fighter production for homeland defense.

These production numbers made the Betty one of Japan’s most numerous bombers, exceeded only by some fighter types in total production. Over four years of war, Mitsubishi delivered approximately 2,400 aircraft to Japanese Navy units across the Pacific theater. The bombers served in every major campaign, participated in every significant naval engagement, and struck targets across distances spanning thousands of kilome.

But production statistics tell only part of the story. Loss rates tell the rest. Few Betty bombers survived to wars end. The overwhelming majority were destroyed in combat, consumed by the fires that the unprotected fuel tanks made inevitable. By August 1945, when Japan surrendered, only a handful of operational Betty bombers remained in service.

The aircraft that had numbered in hundreds in 1942 had been reduced to dozens by attrition that no amount of production could replace. The casualty statistics among Betty crews were similarly devastating, though exact numbers remain difficult to verify from available records. What is certain is that thousands of Japanese air crew died in Betty bombers, their deaths made nearly inevitable by the aircraft’s fundamental vulnerabilities.

The unprotected fuel tanks created conditions where survival depended entirely on avoiding combat damage. Once hit, Betty bombers rarely survived. Once on fire, they never survived. The crews understood these odds and flew anyway because military discipline and cultural values demanded that they accept the risks regardless of consequences. Surviving Betty crews were unanimous in their assessment.

The aircraft’s unprotected fuel tanks made survival a matter of pure chance. No amount of skill, no tactical innovation, no courage could compensate for the fundamental vulnerability built into every G4M. Former flight petty officer Masauato, who completed 28 combat missions before transfer to training duties, offered the most direct summary. The Betty was a magnificent aircraft that asked us to die for its range.

We flew it because we were ordered to fly it. We died in it because that was what it was designed to make us do. The comparison with Allied bomber protection systems highlights the stark difference in design philosophy. The B17 Flying Fortress featured armor plating protecting pilot and co-pilot seats with steel plates ranging from 0.

3 to 0.31 in thick. Armored bulkheads protected crew positions throughout the fuselage. The Bombardia position featured armored glass. Waist gunner positions included protective shields. Self-sealing fuel tanks were standard from the B17C model onward. Introduced in 1941, the B-25 Mitchell incorporated similar comprehensive protection. Pilot and co-pilot seats featured armor backing.

Fuel tanks included self-sealing compounds from early production. The B-25’s empty weight of approximately 9,100 kg reflected the substantial weight penalty of protection systems, roughly 2,000 kg heavier than the Betty. Despite similar size and role, the weight penalty for Allied protection systems was substantial and accepted as necessary.

American studies during the war demonstrated the effectiveness of crew protection measures with statistical precision. Body armor reduced thoracic wound fatalities from 36% to 8%, a reduction of more than 75% in deaths from chest wounds. Self-sealing fuel tanks reduced fire related casualties by similar margins. Aircraft equipped with protected fuel systems showed survival rates three to four times higher than unprotected aircraft when damaged in combat.

Protected crew positions increased survival rates in damaged aircraft by providing shielding from shell fragments and small arms fire. Armored glass prevented pilot casualties from head-on attacks. Bulkheads compartmentalized the fuselage, preventing fire or damage in one section from spreading throughout the aircraft. The comprehensive approach to crew protection reflected American doctrine that trained crews represented assets more valuable than aircraft, which could be replaced more easily than experienced combat veterans. The weight cost for this protection exceeded £1,000

in most American bombers, but American industrial capacity permitted this weight penalty without sacrificing production numbers. American factories produced over 12,000 B17 bombers and nearly 10,000 B-24 Liberators during the war. The production capacity meant that American forces could field large numbers of protected bombers without compromising capability.

Japanese doctrine reached different conclusions. The Betty’s design reflected a calculation that range and striking power outweighed crew survival. This philosophy assumed that achieving surprise and maintaining initiative would provide sufficient protection. It assumed that enemy opposition would remain limited. It assumed that the war would be short and decisive.

All these assumptions proved catastrophically wrong. By mid 1942, American fighter strength increased to levels that made Betty interception routine. By late 1942, American pilots had learned to exploit every Betty vulnerability. By 1943, Betty formations suffered such devastating losses that missions became suicide operations.

By 1944, Betty bombers could barely operate in daylight against American opposition. The mathematics of the Betty’s war were written in fire and loss. Every advantage that made the aircraft formidable in early 1942 became irrelevant once sustained combat began. Range meant nothing when bombers exploded before reaching targets.

Speed meant nothing when fighters could intercept from distant bases. Payload meant nothing when formations were destroyed before weapon release. The examination of tale number 763-12 at Clarkfield in January 1945 revealed the complete story.

The unprotected fuel tanks that shocked Major McCoy were not an oversight, not a temporary expedient, not a design failure. They were the deliberate choice of engineers who believed range mattered more than survival. Japanese designers had created exactly what their specifications demanded. An aircraft with extraordinary range and speed, built with minimal weight, optimized for the mission requirements they received.

The tanks were unprotected because protection would have prevented achieving the required performance. The decision made perfect sense within the constraints of 1937 technology and 1937 assumptions about future warfare. But those assumptions collapsed under the reality of sustained combat against an opponent with unlimited industrial capacity and growing technological advantage.

The Betty bomber became a symbol of Japanese willingness to accept catastrophic casualties in pursuit of tactical advantage. It became evidence of a military culture that valued mission accomplishment over crew survival. When American engineers examined the intact Betty at Clark Field, they were not just analyzing an enemy aircraft. They were witnessing the physical manifestation of choices made years earlier.

Choices that prioritized capability over survival. choices that would cost thousands of Japanese air crew their lives. The unprotected fuel tanks were not an accident. They were a decision. The Betty bomber served from the first day of the Pacific War to the last. It sank capital ships and devastated air bases.

It ranged across distances no other bomber could match, but its ultimate legacy is written in loss statistics that exceeded all projections. The aircraft that opened the war by destroying American air power at Clark Field ended the war carrying Japan’s surrender delegation in white painted aircraft marked with green crosses. The crew of tail number 763-12 had abandoned their aircraft during the American advance on Clark Field.

They had survived by walking away from an aircraft whose design made survival in combat nearly impossible. Most Betty crews were not so fortunate. They flew missions knowing the danger. They climbed into unprotected bombers and crossed vast Pacific distances and they died in overwhelming numbers consumed by fires that the aircraft’s design made inevitable.

The Betty bombers story is ultimately about the price of capability without protection. It demonstrates that performance alone cannot guarantee success when that performance is purchased at the cost of crew survival. The extraordinary range of 6,000 km meant nothing when aircraft could not survive the final 100 km to target.

The impressive speed of 428 km per hour provided no advantage when American fighters could intercept from distant bases with warning from radar systems. The payload capacity of 1 ton became irrelevant when formations were destroyed before weapon release. Most importantly, the Betty reveals that military technology divorced from realistic assessment of combat conditions produces weapons that kill their own crews as efficiently as they strike enemy targets.

The assumptions underlying the Betty’s design, assumptions about limited opposition and short warfare duration, proved catastrophically wrong within months of the Pacific War’s start. By the time these assumptions were proven false, thousands of Betty bombers were already in service or production, and Japanese industry lacked the capacity to replace them with better protected designs.

Japanese designers understood the risks when they made their choices in 1937 and 38. They calculated the weight penalties. They knew the vulnerabilities. They accepted the trade-offs because they believed the performance advantages would prove decisive. They were wrong.

and thousands of men paid the price for that miscalculation with their lives. The Betty’s legacy extends beyond aviation history into fundamental questions about aircraft design, philosophy, military ethics, acceptable risk, and the value of human life in warfare.

American designers answered those questions by prioritizing protection even at the cost of performance. Japanese designers answered differently. It stands as evidence of what happens when capability is prioritized over survivability, when range is purchased with crew lives, when performance requirements override protection considerations. The thousands of burning Betty bombers across the Pacific sky marked the consequences of that philosophical difference, revealing the fundamental difference between how different nations approached warfare in the Pacific. American forces designed aircraft to

bring crews home. Japanese forces designed aircraft to reach targets regardless of cost. In the end, the nation that valued crew survival built an air force that could sustain operations indefinitely. The nation that accepted catastrophic casualties for performance advantages built an air force that destroyed itself through attrition.

The examination of tale number 763-12 at Clark Field provided the final proof of what Allied forces had suspected for years. The Betty bomber was not poorly designed. It was brilliantly designed to achieve specific goals. Those goals simply did not include bringing Japanese crews home alive.

And in that single fact lies the entire story of why Japan lost the Pacific

News

CH2 . Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It… At 0730 hours on November 1st, 1943, Lieutenant General Alexander Vandergrift stood on the bridge of the command ship Macaulay, watching the coast of Bugenville appear through the morning mist. In 2 hours, 14,000 Marines of the Third Marine Division would hit the beaches at Empress Augusta Bay.

Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It… At 0730 hours on November 1st, 1943, Lieutenant General Alexander…

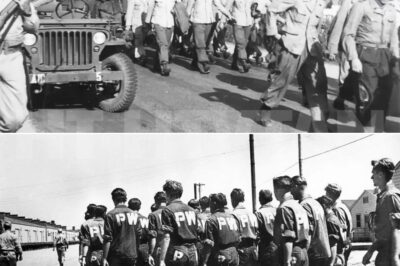

CH2 . German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary, recording words that would have earned him solitary confinement if discovered by his own officers. The Americans must be lying to us. No nation could possess such abundance while fighting a war on two fronts.

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943.Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas.The…

CH2 . When Allied Fighter-Bombers Pounced on Germany’s Elite Panzer Columns — And a Shocked General Watched His Armored Hammer Collapse Before It Ever Reached the Beaches…

When Allied Fighter-Bombers Pounced on Germany’s Elite Panzer Columns — And a Shocked General Watched His Armored Hammer Collapse Before…

Colonel Beat My Son Bloody and Called Me a Liar — Then 12 Minutes Later the Pentagon Called Him Asking If He Knew Who I Really Was…

Colonel Beat My Son Bloody and Called Me a Liar — Then 12 Minutes Later the Pentagon Called Him Asking…

At my grandfather’s funeral, my family inherited his yacht, penthouse, luxury cars, and company. For me, the lawyer handed just a small envelope with a plane ticket to Monaco. ‘Guess your grandfather didn’t love you that much,’ my mother laughed. Hurt but curious, I decided to go. When I arrived, a driver held up a sign with my name: ‘Ma’am, the prince wants to see you.’

At my grandfather’s funeral, my family inherited his yacht, penthouse, luxury cars, and company. For me, the lawyer handed just…

Snow fell softly over the cracked streets of Eastbrook, a forgotten corner of the city where laughter had long gone silent. Streetlights flickered weakly against the biting wind, revealing rows of broken windows, rusted fences, and families doing their best to stay warm. It was Christmas Eve — but here, Christmas was just another cold night.

Snow fell softly over the cracked streets of Eastbrook, a forgotten corner of the city where laughter had long gone…

End of content

No more pages to load