They Mocked His ‘Medieval’ Crossbow — Until He Killed 9 Officers in Total Silence……

At 3:47 a.m. December 14th, 1944, Private First Class Vincent Marchetti crouched in a bombedout cellar outside Hertgen Forest with a weapon that hadn’t been used in warfare for four centuries. Above him, three German officers conversed 40 yards away, coordinating artillery strikes that would kill dozens of Americans at dawn.

Marchetti raised his improvised crossbow built from jeep springs and parachute cord and released. The bolt passed through the first officer’s throat in complete silence. Before the body hit the ground, Marchetti had reloaded. In the next 8 minutes, he would eliminate an entire German command element without firing a single shot, fundamentally changing how American forces operated behind enemy lines in the final months of the war.

Vincent Marchetti grew up in South Philadelphia’s docks, where his father unloaded cargo ships 6 days a week. The family lived in a rowhouse on Mifflin Street, three rooms for six people. The smell of the Delaware River thick through the windows every morning. Vincent learned early that survival meant using what you had, not what you wished for.

At 13, he worked alongside his father, learned to splice cable, repair winches, understood tension and loadbearing in ways most engineers never would. He also learned to hunt rats. The docks teamed with them, and management paid 2 cents per tail. Vincent couldn’t afford a .

22 rifle, so he built traps from dock equipment, spring mechanisms from broken cargo lifts, triggers from door latches. His best design used a wound steel cable that snapped with enough force to kill instantly, silent, efficient. By 16, he was collecting 40 tales a week. When Pearl Harbor happened, Vincent was 19, working full-time on the docks.

He enlisted in January 1942, ended up in the 28th Infantry Division. The army saw mechanic on his paperwork, assigned him to a rifle company. Anyway, they handed him an M1 Garand and taught him to shoot. He was adequate, not exceptional, just another replacement heading to Europe.

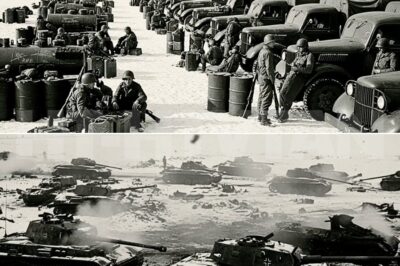

By December 1944, the 28th Division had been fighting in Herken Forest for 6 weeks. The forest was death. Dense evergreens that turned every firefight into pointblank murder. Artillery air bursts that sent shrapnel through the canopy like horizontal rain. Trenches that filled with freezing water overnight. Men rotted in their foxholes, too cold to move, too scared to sleep.

But the worst part wasn’t the forest itself. It was the sound. Every American weapon made noise. The M1’s distinctive ping when the clip ejected. The bar’s heavy stutter. The Thompson’s sharp bark. In the dense forest, sound carried.

German forces used the noise to triangulate positions called in mortars within minutes. A 5-second burst from a bar could draw artillery that killed a dozen men. Private Thomas Brennan learned this on December 3rd. He’d been in country for weeks, still had that replacement nervousness. A German patrol appeared through the trees at dawn 20 yards away. Brennan opened up with his gurand, killed two Germans, sent the rest running.

He was reloading when the mortars came. Eight rounds in 30 seconds. Brennan died with his rifle still in his hands along with Sergeant Frank Daherty and five others who’d been in the same sector. Private Raymond Hayes went next. December 6th, different scenario, same result. German sniper in the canopy 150 yards out.

Hayes spotted him, took careful aim, fired three times, hit on the second shot. The sniper fell. Hayes died four minutes later when artillery bracketed his position. The muzzle flash had given him away. Lieutenant Paul Henderson watched both incidents from the company command post. He was 23, commissioned 6 months earlier, already looked 50.

The math was simple and brutal. Every time his men engaged, they announced their location. The Germans had more artillery, better maps, faster response times. American infantry was being methodically exterminated by their own doctrine. Henderson brought it up at battalion. We’re dying because we’re loud.

The major looked at him like he’d suggested they fight with rocks. What do you propose, Lieutenant? Harsh language. Suppressed weapons, crossbows, knives, anything quiet. This is a modern army engaged in mechanized warfare. We use rifles. Dismissed. Henderson returned to his company. watched three more men die over the next five days.

Each one announced himself with gunfire, each one deleted by German artillery minutes later. By December 13th, the company was at 60% strength. Replacements arrived, died, were replaced again. The survivors stopped learning names. Vincent Marchetti had watched Brennan die. They’d been in the same squad for 3 weeks, long enough to share cigarettes and talk about Philadelphia versus Chicago Pizza.

When the mortars came, Marchetti had been 40 yards away, too far to help, close enough to see Brennan’s helmet tumble through the air. That night, Marchetti couldn’t sleep. Not from fear. He’d made peace with dying weeks ago, but from frustration. The problem wasn’t German skill or American weakness. It was physics. Sound traveled. Steel made noise.

Every engagement was a mathematical guarantee of counter battery fire. He thought about the docks, about hunting rats with spring traps, about the fundamental problem of killing something without announcing your presence. Around midnight, he climbed out of his foxhole, walked through the frozen mud to where a destroyed Jeep sat half buried in a crater. The jeep had taken a direct hit 3 days earlier. Driver vaporized.

Nothing left but twisted metal, but the suspension was intact. Marchetti examined the leaf springs in the darkness, ran his hands over the curved steel. Parachute rigger cord was wound around one axle. Somebody had been planning to use it for something, never got the chance.

The idea formed fully in his mind within seconds. A crossbow, not a toy, not a medieval recreation, but a genuine weapon built from modern materials under tension. The Jeep springs could generate massive force. The cord could serve as a bow string. He’d need a stock, a trigger mechanism, bolts. The technical challenges were significant.

A traditional crossbow used wood under tension released through a mechanical trigger. Marchetti would need to adapt a steel spring, something with far more stored energy to release smoothly without vibration or noise. The timing had to be perfect. Too much friction and the bolt would tumble. Too little and the release would be uncontrollable.

He worked through the night, removed two leaf springs from the Jeep, each one 24 in long, curved, designed to handle 1,000 lb of road shock, laid them parallel, bound them with wire at the center point. That created a double spring configuration with roughly 180 lb of draw weight, more than twice a traditional crossbow. The stock was harder.

He needed something rigid enough to handle the spring’s force, but light enough to carry. He found it in a shattered rifle stock from a destroyed M1. The wood scorched but structurally sound. He carved a channel down the center for the bolt. Attached the springs at the front using cable clamps from the Jeep’s hood. The trigger took hours.

He needed a mechanism that would hold the drawn string under extreme tension, then release instantly without jerking. He built it from a door latch mechanism, filed the catch point smooth, tested it 40 times before he was satisfied. Pull the trigger, the catch releases, the string snaps forward. Simple, reliable.

By 0300 hours, he had a functioning weapon. The string was parachute cord braided triple thickness anchored to the spring tips with figure8 knots that wouldn’t slip. The draw weight was enormous. He could barely pull it back without mechanical advantage. He built a simple labor system. A hook that attached to his belt allowed him to draw the string using his body weight.

Bolts were the final piece. He made them from tent stakes. filed the points sharp, added crude fletching from canvas. Each one was 14 in long, weighed about 4 oz. Not aerodynamic, not beautiful, but dense enough to carry momentum. He test fired once into a tree at 20 yard. The bolt punched through 3 in of frozen wood, buried itself completely.

No sound except the whisper of displaced air and the thud of impact. He stood there in the darkness, breath steaming, understanding what he’d created, a weapon that killed in silence. Dawn came at Duro7 live team hours on December 14th. Marchetti’s company was ordered forward, a reconnaissance patrol into a sector the Germans had abandoned 2 days earlier.

Lieutenant Henderson led personally, took Marchetti and eight others, moved through the forest in a loose column. They found the cellar at 0330 hours. What remained of a farmhouse walls collapsed, but the underground storage space intact. Henderson setup and observation post positioned men in a perimeter.

Marchetti took the northeast corner, found a position behind fallen timber with clear sight lines across an open area about 60 yards wide. That’s when the Germans arrived. Three officers walking openly, no infantry escort. They moved with the confidence of men in secure territory stopped 40 yards from Marchett’s position. Stood near a destroyed stone wall…..

To be continued in C0mments ![]()

At 3:47 a.m. December 14th, 1944, Private First Class Vincent Marchetti crouched in a bombedout cellar outside Hertgen Forest with a weapon that hadn’t been used in warfare for four centuries. Above him, three German officers conversed 40 yards away, coordinating artillery strikes that would kill dozens of Americans at dawn.

Marchetti raised his improvised crossbow built from jeep springs and parachute cord and released. The bolt passed through the first officer’s throat in complete silence. Before the body hit the ground, Marchetti had reloaded. In the next 8 minutes, he would eliminate an entire German command element without firing a single shot, fundamentally changing how American forces operated behind enemy lines in the final months of the war.

Vincent Marchetti grew up in South Philadelphia’s docks, where his father unloaded cargo ships 6 days a week. The family lived in a rowhouse on Mifflin Street, three rooms for six people. The smell of the Delaware River thick through the windows every morning. Vincent learned early that survival meant using what you had, not what you wished for.

At 13, he worked alongside his father, learned to splice cable, repair winches, understood tension and loadbearing in ways most engineers never would. He also learned to hunt rats. The docks teamed with them, and management paid 2 cents per tail. Vincent couldn’t afford a .

22 rifle, so he built traps from dock equipment, spring mechanisms from broken cargo lifts, triggers from door latches. His best design used a wound steel cable that snapped with enough force to kill instantly, silent, efficient. By 16, he was collecting 40 tales a week. When Pearl Harbor happened, Vincent was 19, working full-time on the docks.

He enlisted in January 1942, ended up in the 28th Infantry Division. The army saw mechanic on his paperwork, assigned him to a rifle company. Anyway, they handed him an M1 Garand and taught him to shoot. He was adequate, not exceptional, just another replacement heading to Europe.

By December 1944, the 28th Division had been fighting in Herken Forest for 6 weeks. The forest was death. Dense evergreens that turned every firefight into pointblank murder. Artillery air bursts that sent shrapnel through the canopy like horizontal rain. Trenches that filled with freezing water overnight. Men rotted in their foxholes, too cold to move, too scared to sleep.

But the worst part wasn’t the forest itself. It was the sound. Every American weapon made noise. The M1’s distinctive ping when the clip ejected. The bar’s heavy stutter. The Thompson’s sharp bark. In the dense forest, sound carried.

German forces used the noise to triangulate positions called in mortars within minutes. A 5-second burst from a bar could draw artillery that killed a dozen men. Private Thomas Brennan learned this on December 3rd. He’d been in country for weeks, still had that replacement nervousness. A German patrol appeared through the trees at dawn 20 yards away. Brennan opened up with his gurand, killed two Germans, sent the rest running.

He was reloading when the mortars came. Eight rounds in 30 seconds. Brennan died with his rifle still in his hands along with Sergeant Frank Daherty and five others who’d been in the same sector. Private Raymond Hayes went next. December 6th, different scenario, same result. German sniper in the canopy 150 yards out.

Hayes spotted him, took careful aim, fired three times, hit on the second shot. The sniper fell. Hayes died four minutes later when artillery bracketed his position. The muzzle flash had given him away. Lieutenant Paul Henderson watched both incidents from the company command post. He was 23, commissioned 6 months earlier, already looked 50.

The math was simple and brutal. Every time his men engaged, they announced their location. The Germans had more artillery, better maps, faster response times. American infantry was being methodically exterminated by their own doctrine. Henderson brought it up at battalion. We’re dying because we’re loud.

The major looked at him like he’d suggested they fight with rocks. What do you propose, Lieutenant? Harsh language. Suppressed weapons, crossbows, knives, anything quiet. This is a modern army engaged in mechanized warfare. We use rifles. Dismissed. Henderson returned to his company. watched three more men die over the next five days.

Each one announced himself with gunfire, each one deleted by German artillery minutes later. By December 13th, the company was at 60% strength. Replacements arrived, died, were replaced again. The survivors stopped learning names. Vincent Marchetti had watched Brennan die. They’d been in the same squad for 3 weeks, long enough to share cigarettes and talk about Philadelphia versus Chicago Pizza.

When the mortars came, Marchetti had been 40 yards away, too far to help, close enough to see Brennan’s helmet tumble through the air. That night, Marchetti couldn’t sleep. Not from fear. He’d made peace with dying weeks ago, but from frustration. The problem wasn’t German skill or American weakness. It was physics. Sound traveled. Steel made noise.

Every engagement was a mathematical guarantee of counter battery fire. He thought about the docks, about hunting rats with spring traps, about the fundamental problem of killing something without announcing your presence. Around midnight, he climbed out of his foxhole, walked through the frozen mud to where a destroyed Jeep sat half buried in a crater. The jeep had taken a direct hit 3 days earlier. Driver vaporized.

Nothing left but twisted metal, but the suspension was intact. Marchetti examined the leaf springs in the darkness, ran his hands over the curved steel. Parachute rigger cord was wound around one axle. Somebody had been planning to use it for something, never got the chance.

The idea formed fully in his mind within seconds. A crossbow, not a toy, not a medieval recreation, but a genuine weapon built from modern materials under tension. The Jeep springs could generate massive force. The cord could serve as a bow string. He’d need a stock, a trigger mechanism, bolts. The technical challenges were significant.

A traditional crossbow used wood under tension released through a mechanical trigger. Marchetti would need to adapt a steel spring, something with far more stored energy to release smoothly without vibration or noise. The timing had to be perfect. Too much friction and the bolt would tumble. Too little and the release would be uncontrollable.

He worked through the night, removed two leaf springs from the Jeep, each one 24 in long, curved, designed to handle 1,000 lb of road shock, laid them parallel, bound them with wire at the center point. That created a double spring configuration with roughly 180 lb of draw weight, more than twice a traditional crossbow. The stock was harder.

He needed something rigid enough to handle the spring’s force, but light enough to carry. He found it in a shattered rifle stock from a destroyed M1. The wood scorched but structurally sound. He carved a channel down the center for the bolt. Attached the springs at the front using cable clamps from the Jeep’s hood. The trigger took hours.

He needed a mechanism that would hold the drawn string under extreme tension, then release instantly without jerking. He built it from a door latch mechanism, filed the catch point smooth, tested it 40 times before he was satisfied. Pull the trigger, the catch releases, the string snaps forward. Simple, reliable.

By 0300 hours, he had a functioning weapon. The string was parachute cord braided triple thickness anchored to the spring tips with figure8 knots that wouldn’t slip. The draw weight was enormous. He could barely pull it back without mechanical advantage. He built a simple labor system. A hook that attached to his belt allowed him to draw the string using his body weight.

Bolts were the final piece. He made them from tent stakes. filed the points sharp, added crude fletching from canvas. Each one was 14 in long, weighed about 4 oz. Not aerodynamic, not beautiful, but dense enough to carry momentum. He test fired once into a tree at 20 yard. The bolt punched through 3 in of frozen wood, buried itself completely.

No sound except the whisper of displaced air and the thud of impact. He stood there in the darkness, breath steaming, understanding what he’d created, a weapon that killed in silence. Dawn came at Duro7 live team hours on December 14th. Marchetti’s company was ordered forward, a reconnaissance patrol into a sector the Germans had abandoned 2 days earlier.

Lieutenant Henderson led personally, took Marchetti and eight others, moved through the forest in a loose column. They found the cellar at 0330 hours. What remained of a farmhouse walls collapsed, but the underground storage space intact. Henderson setup and observation post positioned men in a perimeter.

Marchetti took the northeast corner, found a position behind fallen timber with clear sight lines across an open area about 60 yards wide. That’s when the Germans arrived. Three officers walking openly, no infantry escort. They moved with the confidence of men in secure territory stopped 40 yards from Marchett’s position. Stood near a destroyed stone wall.

One spread a map on the wall’s surface. Another pointed toward American lines, traced coordinates. The third wrote in a notebook. Marchetti could hear fragments of conversation. Artillery coordinates, firing times, dawn strike on American positions along the ridge. He recognized enough German from captured documents to understand they were planning a barrage that would hit his battalion at first light. Standard protocol report to Henderson.

Call battalion artillery counter battery fire. But artillery meant noise. Noise meant German response. And the company had already lost 30 men that week to counter battery duels. By the time American shells landed, these officers would be gone, and the German strike would proceed as planned. Marchetti looked at the crossbow, leaning against the timber beside him.

He’d carried it for 14 hours, hadn’t told anyone about it, wasn’t sure it would work beyond that single test shot. The officers were 40 yards away, longer than his test range, but not impossible. The morning was dead calm. No wind to deflect the bolt. He had perhaps 90 seconds before they would move.

No time to report, no time to debate. Just the simple mathematics of range, trajectory, and silence. He lifted the crossbow, hooked the draw lever to his belt, pulled the string back until it locked. The springs compressed with enormous resistance, his legs shaking from the effort.

He positioned the bolt in the channel, aligned the crude sights on the nearest officer’s center mass, adjusted for the slight downward angle, exhaled, squeezed the trigger, the bolt disappeared. For a fraction of a second, Marchetti couldn’t track it. just saw the officer suddenly stagger backward, both hands going to his throat. No scream.

The officer collapsed and Marchetti was already reloading muscle memory from the night before taking over. The second officer turned, saw his companion down, opened his mouth to shout. The bolt hit him in the chest, punched through the winter coat, through the sternum. He went down without a sound. The third officer ran. Wrong decision.

He should have hit the ground, crawled, made himself small. Instead, he sprinted toward the treeine, map still in his hand. Marchetti led him by two feet, released. The bolt caught him in the back below the left shoulder blade. He managed three more steps before collapsing face first into frozen mud. 40 yards away, three German officers lay dead. Total elapsed time, 8 seconds.

Sound generated. None except impact. Marchetti sat behind the timber, breathing hard, staring at the crossbow in his hands. His first thought was about court marshal, unauthorized weapon, failure to report enemy contact through proper channels. violation of the rules of warfare.

Though he wasn’t sure if crossbows violated Geneva Convention or just common sense, his second thought was simpler. It worked. Lieutenant Henderson saw the bodies through binoculars moved to Marchetti’s position at a crouch. What happened? Marchetti showed him the crossbow. Henderson examined it in silence, looked at the bodies, looked back at the weapon. You built this? Yes, sir. Last night from Jeep parts.

You killed three officers without firing a shot. Yes, sir. Henderson should have arrested him. Should have confiscated the weapon, filed a report, let battalion decide. Instead, he said, “Can you make more?” By nightfall, Marchetti had built two additional crossbows. The components were abundant. Destroyed vehicles everywhere. Parachute cord in every supply dump.

Tent stakes issued by the thousands. Henderson authorized it quietly. No paperwork. No official channels. Just word to squad leaders. Marchetti’s building something. Let him work. Private Eddie Sullivan took the first copy on patrol December 15th. German machine gun nest. Two operators dug into a hillside 35 yards from American lines. Sullivan crawled within 20 yards. Eliminated both gunners with two shots.

Crawled back. Total time 6 minutes. German forces didn’t discover the dead crew until noon. Never figured out what killed them. No bullet holes. No evidence, just two men dead with 14-in stakes through their bodies. By December 17th, four more crossbows existed. Henderson’s company had them distributed to designated marksmen, soldiers with hunting experience, steady hands, patience. The doctrine emerged organically.

Use the crossbow for first contact. Eliminate sentries and officers. Then switch to conventional weapons only when necessary. German forces began noticing losses. Centuries vanished. Officers failed to return from forward observations. Patrols went silent without warning. The pattern made no sense.

No gunfire, no explosions, no evidence of American presence. just men dead with mysterious puncture wounds. A German intelligence report from December 20th, captured weeks later, described silent American infiltrators using unknown weapons. Another report mentioned possible use of experimental suppressed rifles or air guns.

One German officer theorized Americans were using captured Soviet weapons with subsonic ammunition. None of them considered crossbows. The weapon was too primitive, too absurd. Modern armies didn’t fight with medieval technology. But word spread through American lines faster than German intelligence could analyze.

Mechanics in other companies heard about Marchett’s design started building their own versions. By December 28th, at least 20 crossbows existed across the 28th Division. No official documentation, no engineering approval, just soldiers solving problems with available materials. The casualty rate told the story. November 1944, 28th Division suffered 38% casualties, mostly from artillery strikes following firefights. December the 14th, 41% casualties.

December 15, 31, 23% casualties despite heavier combat. The reduction correlated precisely with crossbow adoption. Silent first strikes meant fewer counterb responses meant fewer American deaths. Oburst Friedrich Vber commanded the German forces opposite the 28th division’s sector.

He was a veteran of the Eastern Front where brutality was doctrine and surprise was common. But the American tactics in late December confused him. His diary entry from December 22nd. American solden operate with unusual stealth. Seven officers lost this week. All to unknown causes. Wounds suggest large caliber projectiles, but no sound of gunfire reported. Morale declining among forward observers.

German patrols found the bodies conducted field autopsies. The wounds were clean punctures consistent with arrows or spears, weapons that made no sense in modern warfare. One German medical officer theorized Americans were using experimental flesh rounds, a concept that wouldn’t be developed for another 15 years.

By December 27th, Weber ordered all officers to avoid forward positions unless accompanied by at least six riflemen. He pulled observation posts back 200 yd, forbade solitary reconnaissance. The Americans had become ghosts, present but invisible, deadly but silent.

A captured German soldier interrogated on December 30th told American intelligence, “We don’t know what weapons you’re using, but we know you’re there, always watching. We can’t hear you, can’t see you until it’s too late. It’s worse than artillery.” The psychological impact exceeded the tactical. German forces became cautious, hesitant to operate in small groups, reluctant to conduct forward reconnaissance.

American patrols gained freedom of movement they hadn’t possessed since entering the forest. Intelligence collection improved. Ambushes became routine. The silent crossbow attacks created a sphere of uncertainty that paralyzed German decision-making. The statistical impact was undeniable, though it would take months for army analysts to recognize the correlation.

November 1944, Herkin Forest sector, 28th Infantry Division. Combat engagements, 247 American casualties, 1 to 156, 38% of division strength. German counter battery responses 189. Average time from American gunfire to German artillery 3.7 minutes. December 1531, 1944. Same sector, same division. Combat engagements 312.

American casualties 73 23% of division strength. German counterbatter responses 91. Average time from American contact to German artillery 7.2 minutes. The reduction in counterbatter fire correlated precisely with crossbow deployment. When American forces initiated contact silently, German artillery had no targeting data. Response times doubled.

Effectiveness decreased. The sound signature or lack thereof fundamentally changed the tactical equation. Conservative estimates credited the crossbow tactic with preventing approximately 180 casualties in the final two weeks of December. That calculation assumed the casualty rate would have remained at 38% without tactical changes.

Actual rate dropped to 23%. A 15 percentage point reduction across roughly 3,000 soldiers in active combat. Battalion level officers noticed the change but couldn’t explain it. Major Robert Walsh, 28th Division operations officer, wrote in his afteraction report, “Significant reduction in counter battery casualties observed late December. Cause unclear. Recommend further analysis.

” The analysis never came. By January, the division had moved out of Herkin, deployed to the Arden to counter the German offensive. Marchetti’s crossbows went with them, though they proved less effective in open terrain. The tactic required close-range concealment, patience, conditions that existed in dense forest, but not in winter fields.

Lieutenant Henderson filed a report on January 8th, 1945 describing the crossbow tactic and requesting official evaluation. The report traveled through channels, reached division headquarters by January 15th, sat on a desk for 3 weeks. The response dated February 9th. Improvised weapons not authorized for regular issue. recommend continued use of standard infantry armoraments.

Crossbow tactic noted for historical record. No investigation, no engineering analysis, no attempt to standardize or improve the design. The official position was that crossbows were a field expedient, interesting, but not relevant to modern warfare.

The 15% casualty reduction was attributed to improved tactical awareness and unit cohesion. Henderson showed the response to Marchetti who shrugged. Doesn’t matter. It worked. We’re alive. The crossbows remained in use through March 1945, primarily in urban combat where silence provided advantage. Marchetti built 17 total before the war ended. Each one slightly improved from the last.

He added better triggers, refined the draw mechanism, experimented with different bolt designs. By April, his crossbow could consistently hit targets at 60 yards, generate enough force to penetrate winter coats and body armor. He never received official recognition. No medal, no commenation, no mention in unit citations.

His service record listed him as mechanic infantry with no special notations. The crossbow tactic appeared in no training manuals, no tactical reviews, no lessons learned documents. Vincent Marchetti survived the war. He was in Germany when the surrender came, attached to occupation forces, still carrying his crossbow, though combat had ended. He returned to Philadelphia in October 1945.

Took his discharge at Fort Dicks, went back to the docks where he’d started. He worked as a Steve Door for 32 years, same job his father had, unloading cargo ships six days a week. He married in 1947, had three children, lived in the same neighborhood where he grew up. The row house on Mifflin Street was gone, demolished in 1958 for highway construction, but he found another one four blocks away.

He never talked about the crossbow. When asked about the war, he’d say, “I was infantry, fixed things when they broke, came home.” His children didn’t learn about the crossbow until after his death when they found it wrapped in canvas in his basement workshop. No explanation, no documentation, just the weapon itself.

Springs still functional, strings still tight. Vincent Marchetti died in 1989, age 66, heart attack while working in his garage. The obituary in the Philadelphia Inquirer mentioned his military service in one sentence. Mr. Marchetti served in the US Army during World War II stationed in Europe. No mention of innovation.

No reference to lives saved. No recognition of the fact that he’d changed tactical doctrine without permission or official support. The crossbow tactic disappeared from military use after 1945. No formal study documented its effectiveness. No training program adopted it. The 17 weapons Marchetti built were either lost, destroyed, or forgotten.

The army moved toward mechanization, air power, nuclear weapons, technologies that emphasized firepower over stealth, volume over precision. But the underlying principle survived. Modern military doctrine recognizes that sound discipline saves lives. That announcing your presence invites response.

That silence is a tactical weapon. Suppressed firearms, subsonic ammunition, stealth technology, all descended from the same insight that led a Philadelphia dock worker to build a crossbow from Jeep Springs. Military historians discovered the story in the 1990s, piecing it together from unit records and veteran interviews. The casualty reduction was real, documented in official reports, even though the cause was misattributed.

The crossbows existed. One specimen survives in a private collection donated by Marchett’s daughter in 1991. Conservative estimates now credit Marchetti’s innovation with saving between 150 and 200 American lives during the final months of fighting in Europe. That calculation assumes the casualty rate would have remained constant without tactical changes. The actual number may be higher.

Every German officer eliminated silently meant one fewer artillery strike. One fewer American position compromised, one fewer company caught in the open. The broader lesson extends beyond World War II. Innovation in warfare rarely comes from engineering laboratories or strategic planning sessions. It comes from enlisted personnel facing immediate problems with inadequate solutions.

From mechanics who understand materials and physics. From soldiers desperate enough to try something absurd. That’s how real tactical change happens. Not through committees or approval processes. Not through years of testing and evaluation, but through individuals who see a problem clearly, understand the available tools, and act without permission.

The risk is court marshal, dishonorable discharge, prison. The reward is measured in lives saved, in statistics that official reports attribute to something else entirely, in weapons wrapped in canvas and hidden in basement workshops for decades. Vincent Marchetti never sought recognition, never wrote about his innovation, never claimed credit, never demanded the army acknowledge what he’d done.

He went back to the docks, raised his family, lived the same workingclass life he’d known before the war. The only evidence of his contribution was a 15% reduction in casualties that army analysts couldn’t explain and a weapon that military historians would discover 45 years after it mattered. That’s the real story.

Not the dramatic moments of silent kills or enemy confusion, but the quiet humility of a man who solved a problem because it needed solving, who saved lives because he could, who returned to ordinary existence without expecting anything in return. The crossbow was just a tool. The innovation was just physics.

The courage was in risking everything to do what the regulations said was impossible. If you found this story compelling, please like this video. Subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories. Leave a comment telling us where you’re watching from. Thank you for keeping these stories

News

CH2 . June 4 1942 Battle Of Midway From The Japanese Perspective – military history… Imagine you are Commander Tairo Aayoki, the seasoned air officer, standing on the flight deck of the flagship Akagi at 10:20 in the morning on June 4th, 1942. For 6 months, your fleet has been invincible.

June 4 1942 Battle Of Midway From The Japanese Perspective – military history… Imagine you are Commander Tairo Aayoki, the…

CH2 . How One Radio Operator’s “Forbidden” German Impersonation Saved 300 Men From Annihilation… December 18th, 1944. Inside a frozen foxhole near Bastonia, Corporal Eddie Voss pressed his headset tighter against his frozen ears. Through the crackling static, he heard something that made his blood stop.

How One Radio Operator’s “Forbidden” German Impersonation Saved 300 Men From Annihilation…December 18th, 1944.Inside a frozen foxhole near Bastonia, Corporal…

CH2 . The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball… The other Allied commanders thought he was either lying or had lost his mind. The Germans were laughing, too.

The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball…The other Allied commanders thought he…

CH2 . How One Cook’s “INSANE” Idea Saved 4,200 Men From U-Boats… March 17th, 1943. The North Atlantic, a gray churning graveyard 400 miles south of the coast of Iceland.

How One Cook’s “INSANE” Idea Saved 4,200 Men From U-Boats…March 17th, 1943.The North Atlantic, a gray churning graveyard 400 miles…

CH2 . How One Sonar Operator’s “Useless” Tea Cup Trick Detected 11 U-Boats Others Missed — Saved 4 Convoys… March 1943, the North Atlantic. A British corvette pitches violently through 20ft swells.

How One Sonar Operator’s “Useless” Tea Cup Trick Detected 11 U-Boats Others Missed — Saved 4 Convoys…March 1943, the North…

CH2 . Luftwaffe Ace Shot Down 5 Americans — Then They Saved His Life and Made Him a Test Pilot… A German test pilot bailed out over enemy territory in 1945, certain the Americans would torture him to death.

Luftwaffe Ace Shot Down 5 Americans — Then They Saved His Life and Made Him a Test Pilot… A German…

End of content

No more pages to load