The Sinking of Taihō: Japan’s ‘Unsinkable’ Carrier Lost in 1 Day…

The Pacific Ocean, June 1944. An expanse of blue so vast it seems infinite. Yet on this shimmering stage, the final act of a brutal globe spanning war is about to unfold. For the Empire of Japan, the tide has turned. The lightning victories of 1941 are a distant memory, replaced by a grim reality of attrition and retreat. Island after island has fallen to the relentless American industrial machine. A juggernaut that pushes ever closer to the homeland. But in the heart of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s high command, a single powerful doctrine still burns with the ferocity of a religion, Kanti Kessan, the decisive battle. It was a philosophy etched into the very soul of their naval strategy, a belief that one single overwhelming clash of fleets could annihilate the enemy, shatter their will to fight, and secure victory in a single glorious afternoon. This

wasn’t just a strategy. It was an obsession. For decades, every ship designed, every officer trained, every war game played was done in pursuit of this ultimate confrontation. They envisioned a Mahanian clash of battleships and carriers that would echo the legendary battle of Tsushima, where the Japanese fleet had annihilated the Russians 40 years prior.

Now with the American fleet closing in on the Marana Islands, the moment for that final apocalyptic battle had arrived, the plan was cenamed Operation Ago. And it was Japan’s last desperate roll of the dice. At its heart was the first mobile fleet. The last great concentration of Japanese naval power, a magnificent armada of carriers, battleships, and cruisers steaming to meet the enemy.

Leading this charge was Admiral Jizaburo Ozawa, a brilliant but pragmatic commander who knew the odds were stacked against him. His fleet was formidable. But it was a wounded giant. His pilots, once the feared masters of the sky, were now mostly hastily trained rookies, lacking the skill and experience of their fallen predecessors.

His fuel supplies were dwindling, and his intelligence on the enemy’s position was dangerously thin. Yet at the very center of his formation, Ozawa had an ace, a symbol of technological supremacy, and a beacon of hope for an empire on the brink. She was a brand new 30,000 ton super carrier, a floating fortress of steel designed to be nothing less than invincible.

Her name was Taiho, the great Phoenix. As the flagship of this last great fleet, Taiho was more than just a warship. She was the physical embodiment of Kai Kessan. She represented the culmination of all of Japan’s engineering prowess, a weapon forged to withstand the very worst the enemy could throw at her and deliver the decisive blow.

On her armored decks, the fate of the entire operation, and perhaps the war itself rested. The plan was audacious. use the superior range of their aircraft to strike the American carriers from a distance, refuel in Guam, and then strike again, annihilating the US Navy’s core strength before their B-29 bombers could ever threaten Tokyo.

It was a complex, elegant plan, but one that left no room for error. Everything had to go perfectly. But war is never perfect. It is a realm of chaos, chance, and unforeseen consequence. As the great phoenix sailed toward her destiny in the Philippine Sea, a silent, unseen predator was already stalking her from the depths.

The grand cinematic clash of fleets that the Japanese high command had dreamed of for generations was about to be upstaged by a far more intimate and insidious form of warfare. How could a vessel designed to absorb an apocalypse of bombs from the sky be so utterly unprepared for a single unseen threat from below? To understand the great phoenix, one must first understand the fire that gave it birth.

The year is 1942. At the Battle of Midway, the Imperial Japanese Navy, then the undisputed Master of the Pacific, suffered a blow so catastrophic it would permanently alter the course of the war. In the space of a few terrifying hours, four of its finest fleet carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiyu, were transformed into blazing funeral pers.

These were not just ships. They were the very heart of the Kido Bhai, the elite strike force that had brought America to its knees at Pearl Harbor. Their loss was more than a tactical defeat. It was a psychological gut punch that exposed a fatal weakness in Japan’s entire approach to naval warfare.

Before Midway, Japanese carrier design was a breathtaking expression of offensive power. Their ships were built for speed, range, and carrying the maximum number of aircraft. They were the elegant greyhounds of the sea, capable of projecting force further and faster than any of their rivals. But this focus on attack came at a terrible price. They were shockingly vulnerable.

Their hanger decks were cavernous open spaces, and their flight decks were little more than wooden planks laid over an unarmored superructure. They were in effect eggshelled, armed with hammers. A single well-placed American bomb could pierce the deck, detonate amongst the armed and fueled aircraft below, and set off a chain reaction of unstoppable fires and secondary explosions.

Midway proved this theory with horrifying finality. From the ashes of that disaster, a new imperative arose. The admirals in Tokyo, once so confident in their designs, were forced to confront a terrifying new reality. Their carriers could not survive a determined air attack. The next generation of warships could not simply be fast.

They had to be tough. They needed to be anvils, not just hammers, capable of absorbing tremendous punishment and continuing the fight. This radical shift in philosophy gave birth to the Taihaho. Construction had begun in July 1941 at the Kawasaki shipyards in Kobe, but the lessons of the war now shaped her final form.

She would be a revolutionary leap forward, a complete departure from her fragile predecessors. Her most defining feature, and the one that filled the Navy with so much confidence, was her armored flight deck. Unlike any Japanese carrier before her, Taihaho’s deck was an integrated part of the ship’s structure, a colossal slab of 75 mm armor plate laid over 20 mm of steel.

This unprecedented shield was designed to shrug off a direct hit from a 500 kg or 1,000 lb bomb, the very weapon that had doomed the carriers at Midway. For the first time, a Japanese carrier’s flight deck was not a vulnerability, but its primary layer of defense. This innovation was complemented by another first. Her hanger decks were fully enclosed within the armored hull, protecting the volatile heart of the ship from shrapnel and blast waves.

The advanced design didn’t stop there. Her island superructure was blended seamlessly into the hull, and her funnel was angled down and away to keep smoke and heat from interfering with flight operations, features that would become standard on carriers for decades to come. Powered by turbines generating over 160,000 horsepower, she could slice through the waves at a blistering 33 knots, fast enough to outrun any threat and position her air groupoup for a perfect strike.

She was a masterpiece of late war naval engineering, a testament to Japan’s ability to innovate under the most extreme pressure. When she was commissioned in March 1944 and designated Admiral Ozawa’s flagship, she was seen as the ultimate answer to American air power. She was the ship that could not be sunk.

But building a fortress to repel an enemy from the outside creates its own unique set of problems. In sealing the ship so thoroughly against attack, had her designers inadvertently created a new, even more insidious danger, one that was already locked inside with the crew. For all her external strength, the Taihaho was a ship of profound paradoxes.

She was a fortress built to keep death out. Yet, she carried a fatal vulnerability locked deep within her own hull. This was not a flaw you could see on a blueprint. Nor was it the result of a single engineering error. It was a complex and tragic combination of strategic desperation, industrial decay, and the untested nature of her own advanced systems.

A ticking time bomb was installed in the Great Phoenix before she ever set sail, and its timer was set by the declining fortunes of the Japanese Empire itself. The heart of the problem, ironically, was the ship’s own lifeblood, her fuel. By 1944, the silent deadly campaign of the US Navy’s submarine force had effectively severed Japan’s logistical arteries.

The rich oil fields of the Dutch East Indies, once the grand prize of Japan’s conquests, were now largely cut off. The precious highquality crude oil needed for aviation gasoline was reduced to a trickle. What did reach Japan was often unrefined or tarnan crude, a low-grade fuel notoriously rich in volatile, unstable components.

When stored, this gasoline had a terrifying habit of sweating highly explosive vapor. It was less a stable liquid and more a contained explosion waiting to happen. The ship’s designers were well aware of this danger, a common problem across the late war fleet. So, they did what brilliant engineers do. They designed a solution, but was the cure they devised far deadlier than the disease.

Their solution was a sophisticated shipwide mechanical ventilation system. It was a marvel of duct work and fans designed to constantly draw air from the fuel bunkers and other sensitive compartments and vent the dangerous fumes safely out to sea. In theory, it was a perfectly logical and proactive safety measure.

In practice, it was a catastrophic miscalculation. Unlike American carriers, which used multiple smaller independent ventilation systems, the Thai hose was centralized. A single vast network of ducts connected nearly every major space below decks, like arteries connecting to a single heart. This created an unthinkable single point of failure.

If any part of this network was breached, the system designed to expel the poison would instead become its delivery service, pumping an invisible, highly flammable gas to every corner of the ship. How could a system designed for safety become the very instrument of the ship’s destruction? This technological Achilles heel was compounded by an equally dangerous human factor.

The crew that sailed the Taiho into battle was not the elite, battleh hardardened force that had shattered the US Pacific Fleet in 1941. Most of those veterans now lay in watery graves from Midway to the Solomon Islands. Taihaho’s crew of nearly 1700 men were largely green recruits, well- drilled and fiercely loyal. But lacking the priceless intuition that only comes from experience, they were handed the most advanced warship in the fleet, a vessel whose complex systems were still largely untested in the chaos of combat.

Worse, they had been told their ship was invincible, a message that bred a subtle but pervasive overconfidence. They were trained to fight fires they could see and patch holes they could find. who could possibly train them to fight an enemy that was odless, colorless, and silently filling the very air they breathed.

As Admiral Ozawa’s fleet steamed confidently toward its state with destiny, it was sailing directly over a silent, invisible picket line, spread out across the Philippine Sea, was a network of American submarines, a wolf pack of steel sharks tasked with a single purpose, to find the Japanese fleet, and strike the first blow. Deep beneath the waves in the cramped diesel- scented confines of the USS Albaore, Commander James Blanchard and his crew were on patrol.

Life on a submarine was a strange mix of crushing boredom and heartstoppping terror. Long days of silent running punctuated by moments of extreme life or death action. On the morning of June 19th, 1944, their moment arrived. At approximately 7:40 a.m., a contact. The sonar man reported the faint rhythmic pulse of distant propellers, many of them.

Blanch had ordered the submarine to periscope depth. As the slender tube broke the surface, the view that filled its lens was the kind of submarina dreams of his entire career. It wasn’t just a ship. It was the entire first mobile fleet. And there at its very center was a target of unimaginable value.

a massive modern carrier larger than any they had seen before, with a clean, sleek profile that marked it as brand new. It was the Taiho, sailing with the arrogant confidence of a queen, surrounded by her court of destroyers. Blanchard knew instantly that sinking this single ship could the entire Japanese operation before it even began.

The crew of the Albaore sprang into action, a flurry of disciplined activity in the claustrophobic space. They had the target of a lifetime in their sights. But just as they prepared to feed the targeting data into their state-of-the-art torpedo data computer, the mechanical brain that calculated the perfect firing solution, disaster struck. The TDC failed.

The complex system of gears and gyros that could predict the target’s future position with uncanny accuracy was dead. For many commanders, this would have been a mission failure. But Blanchard was a seasoned veteran. He would do it the old way, a manual shot, relying on instinct, experience, and a grease pencil on the periscope glass.

It was a test of pure nerve and skill, a deadly mathematical problem that had to be solved in minutes with no room for error. At 9:09 a.m., with the Taiho filling his periscope, Blanchard gave the order fire. One after another, six Mark14 torpedoes hissed from their tubes, propelled by a blast of compressed air, their own small engines kicking in as they raced toward the flagship.

On the bridge of the Tahoe, a lookout screamed a warning. Torpedo wakes to starboard. On the flight deck, a scene of frantic activity, planes being armed and fueled for the first strike, dissolved into organized chaos. The massive carrier began a hard turn, its hull groaning under the strain. For a moment, it seemed her speed and agility would save her. One torpedo missed, then another.

Two more passed harmlessly a stern. A fifth was dodged with meters to spare. A wave of palpable relief washed over the Japanese crew. But then came the sixth torpedo. It wasn’t a perfect shot, perhaps thrown off by the manual targeting, but it was good enough. It struck the carrier’s starboard side just forward of the island near the aviation gasoline storage tanks.

The impact was not the catastrophic fireb belching explosion one might imagine. It was a solid deep thud that shuddered through the 30,000 ton vessel throwing men off their feet. The ship took a slight lift as water poured into two compartments and the force of the blast buckled the flight deck enough to jam the forward aircraft elevator.

Yet the engines were unharmed. The ship was still moving at speed and could even continue, albeit slowly, to conduct flight operations. The feeling on board was not one of panic, but of vindication. They had taken a torpedo and survived. The armored design had worked. The Great Phoenix was indeed invincible. They were tragically, fatally wrong.

The torpedo had done far more than just punch a hole in the hull. Its concussion had ruptured a series of pipes and the aviation fuel tank itself, starting a slow, almost imperceptible leak of high octane gasoline. They had survived the hunter’s weapon, but in doing so, they had just unleashed a far more patient and deadly killer from within their own hull.

How could the single action meant to save the ship now become the very one that would seal its doom? On the bridge of the Taihaho, the initial shock of the torpedo hit quickly subsided into a sense of controlled, almost defiant optimism. The ship was listing, but only slightly. Her speed was reduced, but she remained underway.

The forward elevator was jammed, a serious inconvenience, but the aft elevator was still functional. Admiral Azawa, watching his crews efficient response, was satisfied. his flagship had absorbed a direct hit from an American submarine and was still in the fight. The reports from below seemed to confirm this assessment.

Flooding was contained and the damage, while not insignificant, was considered manageable. For the next 6 hours, the crew of the Taihaho operated under the fatal illusion that the worst was already over. In reality, the clock on their destruction had just started ticking. Deep within the ship’s mangled bow.

The true danger was spreading not with the roar of an explosion, but with the silence of a creeping fog, the ruptured aviation fuel tank was slowly, steadily weeping its volatile contents into the forward pump rooms and elevator well. The crude, poorly refined gasoline atomized, turning from liquid into a dense, invisible vapor.

Heavier than air, this lethal mist began to pool in the lowest decks, a ghostly, odless lake of pure explosive potential. The crew working nearby to shore up bulkheads and control the flooding had no idea they were wading through an atmosphere that was becoming more combustible with every passing minute.

How can you fight an enemy you cannot see, smell, or hear? It was in this environment of misplaced confidence that a single fateful decision was made. A young, eager damage control officer whose name is now lost to history, surveyed the situation. He correctly identified the leaking fuel as a primary fire hazard. His training dictated that such fumes needed to be vented.

Confronted with a problem that was not in any textbook, he made what seemed to be a logical choice. He ordered the ship’s powerful centralized ventilation system to be run at full blast, intending to draw the dangerous vapors out of the compromised compartments and expel them overboard. It was a decision born of good intentions, but a catastrophic ignorance of his own ship’s design.

What he thought was a lifeline was in fact a lit fuse. The moment the fans spooled up, the ship’s fate was sealed. The system designed to be a safeguard became a super spreader of death. Instead of pulling the fumes out, the powerful draft began sucking the concentrated vapor from the ruptured tank into the main ventilation trunk.

From there, it was methodically and efficiently distributed to nearly every corner of the ship. The very air in the enclosed hanger decks, in the crews mess, in the corridors, and in the machinery spaces, was slowly being replaced with a perfectly mixed fuel air bomb. For six agonizing hours, the men of the Taihaho went about their duties, unaware that their entire world had become a tinder box.

They ate their midday meal, ran electrical cables for repairs, and worked with metal tools, any one of which could have created the fatal spark. They were living, breathing, and working inside a gigantic floating bomb, and they had armed it themselves. As the afternoon wore on, the situation grew ever more perilous. The heat of the day and the warmth from the ship’s own engines would have caused the vapor to expand, forcing it into every last crevice of the vessel’s interior.

Every flick of a light switch, every spark from a running motor, every scrape of a steel door on a steel frame was a roll of the dice. The Great Phoenix, the Invincible Fortress, was now arguably the most dangerous place on the planet. With thousands of sailors performing thousands of tasks, the source of ignition was no longer a matter of if, but simply what and when.

The end came without warning. At 2:32 p.m., Nearly 6 and 1/2 hours after the torpedo strike, the invisible enemy that had saturated the Taiho finally found its spark. The precise trigger will never be known. Perhaps it was a stray electrical arc from a generator, the clash of a dropped tool in a hanger, or simply a static discharge in the vapor-rich atmosphere.

The initial explosion was not the ship shattering cataclysm one might imagine. It was a dull, heavy w, a sudden and violent overpressure deep within the ship’s enclosed hanger. For a fleeting second, the men on deck may have looked at each other in confusion, wondering what it was. They would not have to wonder for long.

That first detonation was merely the pilot light. What followed was a chain reaction of apocalyptic fury. The first blast wave traveling at the speed of sound flashed through the ventilation ducts, igniting the fuel air mixture in every connected compartment simultaneously. A split second later, the main hanger deck, now essentially a 600 ft long fuel bomb, erupted.

The force of the detonation was so immense that it had nowhere to go but up. The mighty armored flight deck, the 75 mm shield that was the ship’s entire reason for being, became the cap on a bottle of gasoline. It was blown clean off its supports, buckling and ripping upwards with a scream of tortured metal. Huge sections of the 3-in thick steel plate were hurled hundreds of feet into the air, tumbling end over end before crashing back down into the sea.

The Taihaho was being torn apart. not by an external enemy, but by its own internal combustion. The fortress had become a volcano. A towering column of black and orange fire erupted from the ship’s midsection, followed by a shower of debris and human bodies. The blast wave killed hundreds of men in an instant. Below decks, it was even worse.

Secondary explosions began to tear through the ship’s bowels as the inferno reached the ready use ammunition and armed aircraft. Torpedo warheads and 500lb bombs cooked off. Each detonation ripping another massive hole in the ship’s structure, collapsing bulkheads and turning compartments into channel houses.

The ship that was designed to withstand a dozen bomb hits from above was now being gutted by dozens of bomb-sized explosions from within. On the bridge, Admiral Ozawa and his staff were thrown to the deck as their world disintegrated around them. He watched in stunned horror as his flagship, his invincible symbol of hope, was consumed by a fire that could never be fought.

The integrity of the ship was gone. Fires raged out of control, fed by the very air that was being sucked into the gaping wounds in her hull. The ship began to list heavily to port, the angle increasing with terrifying speed as compartment after compartment flooded. The order to abandon ship was almost a formality.

The vessel was already in its death throws. Ozawa’s staff had to physically drag him away, pleading with him to transfer his flag and command of the fleet to the cruiser Haguro. Leaving his dying ship and its doomed crew was the hardest order he would ever obey. As his barge pulled away, he got a final horrifying view of his flagship’s agony.

The Great Phoenix was a ruin, wreathed in smoke and fire, her proud silhouette broken and sagging. At 4:28 p.m., less than 2 hours after the first spark, the final convulsive explosion occurred. A massive blast deep in the hull signaled the end. The Taihaho’s back broke. She rolled heavily onto her side, hung there for a moment, as if in a final defiant salute, and then slid stern first beneath the waves of the Philippine Sea.

She took with her an estimated 1,650 officers and men, nearly her entire compliment. The ocean, which had moments before been the stage for a technological titan, was now empty, save for oil slicks, debris, and the desperate survivors. How could a nation’s greatest hope meet such a swift, violent, and self-inflicted end? The column of smoke that marked the Taihaho’s grave, was a funeral p for more than just a single ship.

It was a beacon signaling the death of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s offensive capability. Just hours earlier, the veteran carrier Shokaku had also been sent to the bottom by another American submarine, the USS Cavala. This devastating one-two punch decapitated Admiral Azawa’s command structure and robbed his returning pilots of their primary landing decks.

When the young exhausted Japanese aviators arrived back from their long-range strikes, they found their homes gone, forcing them to ditch in the sea or attempt landings on the remaining carriers, leading to a scene of chaos that compounded the aerial slaughter the Americans would grimly dub the Great Mariana’s Turkey shoot.

The decisive battle Japan had gambled everything on was over before it had truly begun. But the real legacy of the Taiho is not found in the tactical minutiae of that battle. Her story is a perfect tragic microcosm of Japan’s ultimate defeat in the Pacific War. Her sinking was not the result of a lack of courage, a deficiency in engineering genius, or the overwhelming power of the enemy. It was a systemic failure.

A death by a thousand cuts inflicted long before she ever met the enemy. Japan had the will to conceive of a revolutionary warship, but its crumbling industrial base could only provide the volatile, low-grade fuel that made her a tinderbox. They had the skill to build her, but the staggering attrition of a long war meant they could only man her with an inexperienced crew, leading to the fatal error in damage control.

The Taihaho was a fortress built to fight the last war, an answer to the dive bombers of Midway. She was designed to survive a 100 hits from the outside, but was ultimately killed by a single unlucky blow that unleashed a poison from within. Her final agonizing death was not a glorious battle against a worthy foe, but a slow internal collapse caused by the convergence of her own hidden flaws.

She wasn’t simply sunk by an American torpedo. She was a victim of a promise betrayed not by the enemy but by the bitter inescapable realities of a war Japan was now destined to lose. In the end, we are left to wonder, is the greatest threat to any fortress the enemy battering its gates or the fatal floor we unknowingly build into its very foundations.

[Music]

News

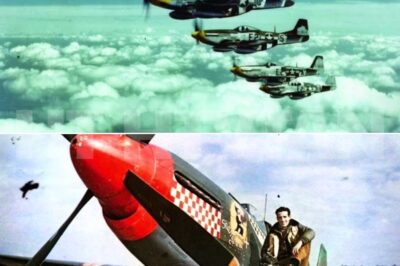

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

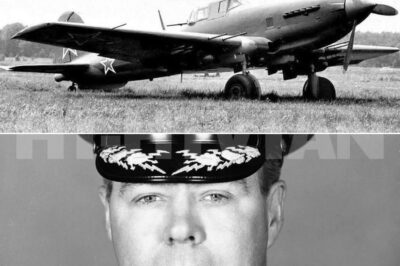

CH2 . America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped as North Korean fighters strafe the runway, destroying transports one by one. Enemy armor is twenty miles away and closing. North Korean radar picks up five unidentified contacts approaching from the sea. The flight leader squints through his La-7 canopy.

America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped…

CH2 . Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above Cape Bon, Tunisia.

Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above…

CH2 . Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles northwest of Lelay, New Guinea. The oil blackened hand trembled as a Japanese naval officer gripped the splintered remains of what had once been part of the destroyer Arashio’s bridge structure. His uniform soaked with fuel oil and seaater, recording in his mind words that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles…

CH2 . Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on April 18th, 1942 fundamentally altered the Pacific Wars trajectory, forcing Japan into a defensive posture that would ultimately contribute to its defeat.

Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on…

CH2 . German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of December 1944, the German war machine, a beast long thought to be dying, had roared back to life with a horrifying final fury. Hitler’s last desperate gamble, the massive Arden offensive, known to history as the Battle of the Bulge, had ripped a massive bleeding hole in the American lines.

German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of…

End of content

No more pages to load