The Rifle the Army Tried to Erase — Until One Defiant Farm Boy Used It to Hunt Down Nine Japanese Snipers Before Dawn…

History gives its medals to the officers whose signatures appeared on operation papers, but the ground truth of war was always decided by the men who lay in the mud far below them, the ones who did not possess authority, only fear, sweat, instinct, and the stubborn will to stay alive. At exactly 6:47 a.m. on November 24th, 1943, on the steaming, disease-ridden soil of Bougainville Island, that reality pressed down upon Private First Class Raymon Vandermir with the crushing force of inevitability. He crouched deep inside a foxhole already half-filled with the previous night’s rainwater, mud climbing up the sleeves of his fatigues, the smell of rotting vegetation mixing with cordite and mildew. He understood, with a harsh clarity formed not from textbooks but from surviving too many close calls, that American military doctrine was about to deliver his entire unit into the jaws of death.

What confronted him was not a matter of bravery, discipline, or even marksmanship; it was a mathematical impossibility disguised as a tactical framework. Through a dissolving curtain of early-morning fog and the coarse, razor-edged kunai grass that thickened the jungle’s floor, Vandermir saw nine Japanese scouts—silent, deliberate, predatory—moving toward Company K’s defensive position. They were 180 yards out. On a flat European pasture, 180 yards represented a distance easily conquered by a competent rifleman, a near-routine shot during training. Yet the Pacific was indifferent to such assumptions. Here, the light warped itself around the humidity, the vines interfered with aim, and the dense palette of greens distorted depth perception until the jungle seemed to shift and breathe. In this place, 180 yards was not merely far; it was an illusion, a concept without practical meaning, because doctrine insisted that no soldier could reliably strike a moving target through this suffocating environment at such a range.

Doctrine demanded patience. Doctrine demanded that the enemy come closer. Doctrine demanded that Vandermir sit still, wait, and trust that someone in an office thousands of miles away had understood the terrain better than the men who had to bleed on it.

But Vandermir, blinking through the fog as he counted the nine scouts once, then again, recognized the fatal flaw behind that assumption. These were not infantry. They were scouts. Their purpose was not to engage. Their purpose was to map the defensive line, identify weak points, chart firing arcs, and radio back the information that would determine how many Americans survived the next assault. If he allowed nine highly trained Japanese scouts to close the distance and complete their mapping, Company K would be exposed, disoriented, and likely cut apart before the sun had risen fully above the canopy. Vandermir did not need a briefing to understand how quickly an entire perimeter could collapse when the enemy possessed precise knowledge. He simply knew that if he obeyed doctrine, men he had eaten with, marched with, and joked with in the bitter hours before sleep would be corpses by morning.

Beside his soaked boot rested his standard-issue Springfield M1903 rifle, the weapon that officers praised for its reliability and that training manuals hailed as the backbone of American infantry skill. It was, undoubtedly, a respectable instrument of war. Yet Vandermir looked at it with a skeptical disdain born from lived experience rather than theoretical instruction. The Springfield was long, front-heavy, and difficult to maintain a stable hold in a foxhole filled with slick mud, especially when the targets were camouflaged within a horizon of endless green. The weapon shook at the wrong moment, shifted when the grip weakened, and required a precise firing stance nearly impossible to achieve when trapped inside a cramped, uneven fighting position.

So Vandermir ignored it.

Instead, his hands closed around the weapon that had almost gotten him court-martialed, the weapon that violated regulations so thoroughly that his commanding officer, Captain Thornton, had once threatened to drag him before a tribunal. To anyone without context, the rifle looked like a salvaged disaster: a frame reinforced by scrap wood scavenged from crates, sections reinforced with aluminum stripped from damaged aircraft parts, and a profile that the Army would have dismissed as unstable, unprofessional, and dangerously improvised. Military hierarchy labeled it a blatant unauthorized modification of government property, a punishable offense. The Japanese, however, were on the brink of learning that practicality mattered more than doctrine, and that survival often belonged not to the most polished weapon, but to the one adapted to the unforgiving reality of the battlefield.

Vandermir called it the Hay Rack.

The Hay Rack had no prestigious origin. It was not engineered in a weapons facility. It was not tested, refined, or issued by the war department. It was born decades earlier on a small patch of land in Sioux City, Iowa, where Vandermir’s family had farmed 240 acres that offered more heartbreak than profit. When his father collapsed in the North Field from a heart attack, twelve-year-old Raymon had stepped into a role no child should shoulder, learning hard lessons about resourcefulness, necessity, and desperation. On an Iowa farm, innovation came not from luxury, but from survival. If a tool broke, you repaired it with what was lying around. If pests destroyed your crops, you improvised a solution or faced starvation. The Hay Rack rifle, originally devised by his grandfather in 1891 to deal with groundhogs that threatened the family’s livelihood, was one such invention—a crude yet effective tool refined not by scientists, but by generations of men who refused to be defeated by circumstances.

It was ugly. It was ungainly. It broke every rule of military procedure. And yet on that morning in Bougainville, as Vandermir steadied the weapon’s makeshift support against the lip of the foxhole, it felt like the only instrument on Earth capable of bridging the impossible distance between him and the nine scouts closing in with silent precision. He inhaled slowly, letting the humid air fill his lungs while the jungle seemed to hold its breath, waiting for the moment that would decide whether Company K lived or died.

Within the next ten minutes, six of those nine scouts would fall—one after another, not in a spray of chaotic gunfire, but in deliberate, methodical succession, each shot finding its mark despite the impossible terrain, the oppressive humidity, and the illusion-warping vegetation. They would not be killed by artillery, airstrikes, machine gun nests, or coordinated company fire. They would be killed by a single farm boy from Sioux City using a banned rifle that should never have existed according to regulation, a rifle that proved that survival demanded adaptation long before it demanded obedience.

And the story of how a piece of improvised scrap wood reshaped American sniper doctrine did not begin with medals or heroic commendations. It began with fear, mud, desperation, and a moment where Vandermir had to choose between following the safe, sanctioned rules or acknowledging the brutal truth that those rules had never been written for jungles like this or for mornings like this one.

What happened in the minutes after the sixth scout fell would push Vandermir toward the edge of another decision—one far more dangerous, far more uncertain, and far more costly than the first…

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

History often remembers the generals who signed the orders, but it rarely remembers the farm boys who had to survive them. At 6:47 a.m. on November 24th, 1943, Private First Class Raymon Vandermir was crouching in a muddy foxhole on Bougainville Island. Realizing that American military doctrine was about to get his entire unit killed.

The situation in front of him was a mathematical impossibility. According to the U.S. Army, through the lifting fog and the thick kunai grass, Vandermir was watching nine Japanese scouts creeping toward his perimeter. They were exactly 180 yards away. Now in a European field, 180 yards is a chip shot for a trained rifleman.

But in the dense, rotting vegetation of the Pacific Theater, 180 yards might as well have been on the moon. The jungle swallows depth perception. The light plays tricks on you. Standard infantry doctrine said you couldn’t effectively engage a moving target at that distance. You had to wait until they were close.

But Vandermir knew that if he let nine scouts get close enough to map Company K’s defensive line, half his friends would be dead by sunrise. Beside him in the mud lay his standard issue. Springfield M1903. It was a fine weapon for a parade ground, but in this foxhole Vandermir considered it useless. It was too unstable, too difficult to hold steady in the slick mud against camouflaged targets, so he ignored it.

Instead, he gripped a weapon that violated every standing regulation in the infantry manual. It was a rifle that would eventually lead his commanding officer, Captain Thornton, to threaten him with a court martial. To the untrained eye, it looked like a piece of garbage, a crude contraption held together with scrap wood and stolen aircraft aluminum.

The military establishment called it an unauthorized modification of government property. The Japanese were about to call it unfair, but Vandermir simply called it the Hay Rack. This wasn’t a weapon born in a laboratory or designed by ordnance officers in air conditioned offices in Brisbane.

It was born in the depression era dust of Sioux City, Iowa. Vandermir had spent his childhood on 240 acres of corn and soybeans that barely turned a profit when his father died of a heart attack in the North Field. 12 year old Raymond took over. And on an Iowa farm, you learn quickly that if you can’t solve a problem with what you have lying around the barn, you starve.

The Hay Rack was the solution his grandfather had devised. Back in 1891, to stop groundhogs from destroying their livelihood. It was ugly. It was ungainly. And it was about to change the course of the Pacific War. Within the next ten minutes, six of those nine Japanese scouts would be dead. They wouldn’t be killed by an airstrike or a machine gun nest.

They would be eliminated one by one, methodically, by a farm boy using a banned rifle that violated every regulation in the manual. The story of how an illegal piece of scrap wood rewrote American Sniper doctrine doesn’t begin with glory. It begins with dirt, desperation, and a choice between following the rules or staying alive.

If you ask any military historian about the tools of World War Two, they will point to the M1 Garand. General Patton famously called it the greatest battle implement ever devised. And on paper, he was absolutely right. It gave a squad of American riflemen a massive volume of fire, eight rounds of semi-automatic destruction that could suppress an enemy position in seconds.

But paper statistics are written by men in offices, not men in mud. When Raymond Vandermir arrived on Bougainville during the November 1st landings, he quickly realized that the commanders sitting in headquarters didn’t understand the geometry of the jungle. They believed in fire superiority. The idea that if you throw enough lead downrange, you win.

However, the Japanese Imperial Army had stopped fighting that kind of war months ago. They weren’t interested in volume. They were interested in invisibility. On Bougainville, the enemy wasn’t a formation of soldiers. You could suppress. The enemy was a ghost. They fought from spider holes dug deep into the root systems of banyan trees, or from platforms camouflaged so perfectly in the canopy that you could walk right underneath them without looking up.

The Japanese tactic was psychological as much as it was physical. They sent scouts, small teams of 2 or 3 men to probe the American lines at dawn and dusk. These weren’t banzai charges. They were surgical strikes designed to bleed American units one man at a time.

The M1 Garand, built for rapid fire at close range, was useless against a single man hiding 200 yards away in a dense thicket. You can’t suppress a target. You can’t see, and you can’t close with an enemy who vanishes before the brass casing hits the ground. The cost of this tactical mismatch was paid in blood, and the receipts were piling up across the Pacific.

Consider the case of private Eddie Larsen on Guadalcanal. He was a Minnesota boy. Probably grew up hunting, just like Vandermir. A Japanese scout had been hiding in a palm tree for six hours, waiting. When Larsen stepped out, the scout put a bullet through his throat from 40 yards away. Larsen bled out in 90 seconds. His entire squad emptied their Garands into the jungle, shredding the vegetation, but they never hit a thing. On New Georgia, the story was even worse.

Corporal James Rutherford walked within ten feet of a camouflaged pit. The scout inside didn’t panic. He waited. He let Rutherford pass, then shot him in the back. By the time the squad circled back to the pit, it was empty. This wasn’t combat. It was execution. When Vandermir’s Unit company K pushed inland on Bougainville, the ghosts followed them.

In the first two weeks alone, they lost two good men to scouts operating from over 150 yards away, a range where the Garand’s thick iron sights covered up the entire target. The first was Private Tommy Whitaker from Tennessee, killed on November 8th. He was just 20 years old, carrying ammunition forward to the line. A single shot took him in the chest.

Vandermir remembered Whitaker because he was the kind of kid who’d give you the shirt off his back. Whitaker died in the mud, asking for his mother a few days later, on November 12th. It was Corporal Vincent Calibracy, a former longshoreman from Brooklyn. Tough as nails. He was shaving when the bullet hit him in the temple. He was dead before he hit the ground.

The army’s response to this slaughter was typical of a large bureaucracy. They threw a different standard issue tool at the problem. Officers began distributing Springfield M1903 bolt action rifles to designated marksman one per platoon. The logic was sound.

In theory, the Springfield was more accurate than the Garand and had better range, but in practice it solved nothing. Why? Because the standard issue Springfield sights were still designed for general infantry use. They were too coarse for precision work against a target the size of a helmet at 200 yards in low light. Furthermore, the jungle floor fought the shooter to get steady. You need a prone position, but on Bougainville, prone meant lying in six inches of mud, tangled in roots that blocked your line of sight.

If you stood or kneeled to clear the vegetation, the rifle wobbled. Your heart rate, your breathing, the fatigue. It all transferred to the barrel. Vandermir was handed one of these Springfield’s. He tried to make it work. He tried to find a clean firing position, but the mechanics were against him. The wobble was uncontrollable and the sights were inadequate.

The tragedy culminated on November 15th with Private Leo Fischer. Fischer was from Wisconsin, sitting just 20ft from Vandermir. Eating his breakfast. A scout fired from a tree line 175 yards away. The bullet entered below Fischer’s left ear and exited his right eye. Vandermir watched the medics cover Fischer’s body.

He watched them pack up his wallet and the photos of his family, and he realized that as long as they played by the Army’s rules using standard weapons and standard configurations, they were just targets waiting for their turn. The M1 Garand had failed them. The standard Springfield had failed them. If Raymon Vandermir wanted to stop the ghosts killing his friends, he was going to have to stop thinking like a soldier and start thinking like a farmer.

And to understand how a piece of scrap wood defeated the Imperial Japanese Army, you first have to understand the economy of an Iowa farm. During the Great Depression, for the military, a missed shot is a tactical error for the Vandermir family. Working 240 acres of corn and soybeans outside Sioux City. A missed shot was a financial disaster. Ammunition was expensive.

If you pulled the trigger, something had to die or you didn’t eat. That night in his foxhole. With the image of private Fischer’s body fresh in his mind, Vandermir wasn’t thinking about Army field manuals. He was thinking about his grandfather. The elder Vandermir was a Dutchman who had homesteaded that land back in 1891.

He was a man who viewed inefficiency as a sin and groundhogs as a plague. The farm had a serious infestation, and groundhogs are small, skittish targets that stay low in the grass. Not unlike the Japanese scouts currently bleeding company K dry. The problem with shooting a rifle, whether it’s at a groundhog or a soldier, is biology.

The human body is a terrible firing platform. Your heart beats sending micro tremors through your hands. Your lungs expand and contract, shifting your point of aim, your muscles fatigue. Introducing wobble. At 50 yards, this wobble is negligible. At 200 yards, a millimeter of movement at the muzzle becomes two feet of air at the target.

Most soldiers try to muscle through this. They grip the rifle tighter. But Vandermir’s grandfather understood physics better than he understood farming. He realized that to hit a small target at a distance, you had to take the human element out of the equation.

Decades earlier, he had taken an old Winchester lever action rifle and stripped off the standard stock. In its place, he built what he called the Hay Rack. It was an engineering monstrosity. It consisted of a crude wooden platform that extended forward from the trigger assembly, running underneath the barrel. It looked like a splint on a broken leg, but the logic was brilliant.

The extended flat surface allowed the shooter to rest the rifle on literally anything a fence post, a hay bale, a log without the barrel touching the object. In ballistics. You never want the barrel to touch a hard surface, because the jump from the recoil throws off the shot. The Hay Rack absorbed that movement. More importantly, it shifted the center of gravity.

Instead of the shooters supporting the weapons weight with their muscles, the environment supported the weapon. The rifle became a mounted instrument, stable as a table saw. This was the Hay Rack special. It was ungainly, ugly, and effective. By the time Raymond was 14, he wasn’t just shooting. He was performing pest control. He could consistently decapitate groundhogs at 220 yards. By 16, he was dropping coyotes at 300 yards.

Raymond wasn’t the captain of the football team. He wasn’t quick with his fists and he wasn’t popular at school. But on the flat plains of Iowa, where the wind cuts across the furrows. He possessed a lethal skill set developed through necessity. He learned that if you can stabilize the weapon, the distance doesn’t matter.

Now, sitting in the mud of Bougainville, Vandermir looked at the problem facing company K. The Japanese scouts were winning because they were operating in the wobble zone. That distance, where an unsupported American soldier couldn’t hold steady enough to hit them. The Army’s solution was to shout, get closer! Vandermir’s solution was to change the physics of the engagement. He didn’t need a new rifle.

He didn’t need more men. He needed a piece of wood. He realized that the jungle was full of natural rests, logs, sand bags, roots. If he could recreate his grandfather’s rig, he could turn the chaos of the jungle into the stability of a fence post. But there was a catch in Iowa. Modifying your rifle was ingenuity. In the United States Army.

It was a court martial offense. To save his friends, Vandermir would have to become a criminal. In the military, there are two kinds of rules. The ones that keep you safe and the ones that get you killed. Raymond Vandermir decided that the rule against modifying weapons belonged in the second category. But deciding to break the law is one thing.

Pulling it off in a combat zone is another. The logistical challenge was immense. Vandermir needed materials that didn’t exist in the infantry supply chain. He needed lumber. He needed rigid metal struts, and he needed tools. He had a trench knife and a flashlight. It started on November 18th. After evening chow, Vandermir began prowling the supply dump like a stray cat.

He found his base material in a discarded ammunition crate, rough pine full of splinters but sturdy. He pried loose a plank about 18in long and four inches wide. Nobody stopped him. Soldiers scavenged wood all the time to reinforce foxholes or build dry seats.

To the MPs, he just looked like another miserable grunt trying to stay out of the mud. But wood wasn’t enough. The critical engineering challenge was the vertical struts. He needed something to connect this wooden platform to the rifle’s barrel band without throwing off the balance. It had to be light, but rigid. He found the solution in the motor pool. The heart of the battalion’s mechanical operations. It was late, around 11 p.m..

The air was thick with the smell of diesel rotting vegetation and the standing water that bred millions of mosquitoes. Vandermir spotted a damaged aircraft part likely from a downed fighter or a transport plane. It had aluminum tubing. Aluminum was gold, lightweight, rust proof strong.

He walked casually past the motor sergeant, who was buried in paperwork inventorying truck axles. With a quiet confidence born of necessity. Vandermir liberated two six inch sections of tubing, three quarters of an inch in diameter. Back in his foxhole, the real work began. This was treason. By candlelight under the cover of a poncho to hide the light. Vandermir went to work. He didn’t have a drill, so he improvised.

With the kind of stubborn ingenuity you only find on a farm. He took a nail and heated it over a can of Sterno cooking fuel until it glowed cherry red. Then he pushed the hot metal through the pine plank to bore his mounting holes. It was slow, agonizing work. The smell of burning wood mixed with the jungle damp.

His hands were blistered from gripping the hot nail with pliers. Blackened by soot, he worked by feel as much as by sight. Tucking the flashlight between his shoulder and cheek. He used wires scavenged from a communication cable to lash the aluminum struts to the barrel band. At 115, a m on November 19th, he held it up. It was hideous. It looked like a Frankenstein creation.

A crude wooden paddle wired to the front of a precision military instrument. It violated Army Regulations 750-10, which explicitly stated rifles will be maintained in standard configuration without alteration. If Captain Thornton saw this, Vandermir would be facing a court martial. He would be destroying government property. But then Vandermir tested it. He rested the platform on a sandbag and looked through the sights. The difference was instant.

The front sight post didn’t dance. It sat still, frozen on the target. The wobble that plagued every other shooter in the regiment was gone. The next morning, during a lull in the fighting, he fired three rounds at a tree stump 225 yards away. Bang bang bang. All three shots clustered into a circle the size of a saucer, with a standard rifle and iron sights.

He would have been lucky to hit the stump at all with the Hay Rack. He was surgical. He had built a career ending device. But as he looked at that tight grouping in the wood, he knew something else. He had just built the only thing that could stop the ghosts. To understand the violence that exploded on the morning of November the 24th.

You first have to understand the grief that fueled it. Regulations and court martials are abstract concepts. Watching your tent may die while holding a picture of his children is very real. Two days prior, on November 22nd, Corporal Danny Fletcher, a former auto mechanic from Akron, Ohio, had been killed by a single shot from a ridge 190 yards out.

Fletcher was Vandermir’s friend. They shared rations. They dug ditches together. Fletcher had spent the previous evening showing Vandermir photographs of his two little girls back home. He died slowly. It took 12 minutes for him to bleed out from a gut shot, calling for his wife the entire time.

Vandermir listened to every second of it, unable to return effective fire because the enemy was simply too far away for standard equipment. That sound, the sound of a good man dying for no reason other than range limitations, was ringing in Vandermir ears when he climbed into his foxhole on the northeastern edge of the perimeter. The morning of November the 24th brought the fog in the Pacific.

Fog isn’t just weather; it’s a weapon. It was thick, wet and clung to the kunai grass like a physical barrier, cutting visibility down to maybe 60 yards. Vandermir sat there wet and miserable, with his unauthorized Hay Rack Springfield resting across the sandbag. He had covered the action with a poncho to keep the moisture out. Around 6:30 a.m., the curtain started to lift.

The fog didn’t burn off all at once. It receded slowly, revealing the landscape and patches. At 6:47 a.m.. Vandermir saw the movement. It was subtle at first, just a disturbance in the high grass, 180 yards away. It could have been the wind. It could have been a wild pig. But the hairs on the back of Vandermir’s neck stood up.

He watched through his sides, barely breathing, waiting for the shapes to resolve. 30s. Later, the ghosts appeared. They were moving in a loose formation. Low and careful. Nine Japanese scouts. They weren’t attacking. They were mapping. Their job was to identify the American machine gun nests in foxholes, withdraw, and then bring down mortar fire on those exact coordinates.

If Vandermir let them finish their work, company K would be decimated before breakfast. He did the math instantly. They were 180 yards out at that range. The M1 Garand is a suppression weapon, not a precision instrument. If he opened up with a Garand, he might hit one, but the other eight would vanish into the jungle if he called for the sergeant. The noise would alert them. He was alone.

Vandermir settled on the Hay Rack platform onto the sandbag. This was the moment of truth for his depression era invention. The wooden platform bit into the sandbag, anchoring the rifle. The weight distributed perfectly. He looked through the rear. Peep site. The front post didn’t float; it sat rock-still on the chest of the lead scout. He worked the bolt.

Feeling the mechanical snick. Click as a thirty-aught-six round chambered. The nearest scout was moving through a gap in the grass. Confident in his distance, Vandermir exhaled, paused at the bottom of the breath, and squeezed crack. The rifle bucked, but the platform kept it true. The lead scout dropped instantly.

Now here is where the psychology of distance comes into play. The other eight scouts froze for maybe two full seconds. They didn’t move. They didn’t dive for cover. They didn’t return fire. Why? Because they believed they were safe. Japanese intelligence told them that Americans couldn’t shoot accurately at 180 yards. They assumed it was a stray round or luck.

That hesitation cost them everything. Vandermir worked the bolt. Click clack chambered a second round and found the second scout. The post settled. He fired the second man dropped with a clean hit to the center mass. Now the remaining seven understood the illusion of safety shattered. They scattered, dropping flat into the kunai grass, trying to crawl backward toward the tree line.

In a normal engagement, they would have survived. A soldier firing from his shoulder, standing or kneeling to see over the grass would be wobbling too much to hit a crawling man. At nearly two football fields away. But Vandermir wasn’t fighting a normal engagement. He was fighting from a bench rest. The Hay Rack gave him the stability of a concrete pillbox.

He tracked a third scout who was trying to scramble through the heavy vegetation. He fired the bullet, took the man in the shoulder. The scouts stumbled, but kept moving. Vandermir didn’t panic. He cycled the bolt, reacquired the target, and fired again. The scouts stopped moving. Three down, six remaining. The fog was lifting faster now, clearing the stage for what was becoming a massacre.

The scouts realized they couldn’t crawl fast enough, so they abandoned stealth for speed. They had 180 yards of open ground cover to reach the safety of the jungle canopy. A fourth scout made a break for it. He stood up and sprinted for the trees, shooting a running target at that distance with iron sights is one of the hardest shots in warfare.

You have to lead the target, aiming at where he will be, not where he is. Vandermir swung the rifle on its wooden pivot. He led the runner by two feet. Crack. The Scout’s legs folded under him, and he went down hard. Four down. Now the enemy was desperate. Two scouts stopped running and opened fire on Vandermir position. They were trying to suppress him to keep his head down so the others could escape.

Their Arisaka rounds cracked past his foxhole, thumping into the sandbags. Vandermir ducked, counted to three, and came back up. He didn’t just pop up and spray fire. He returned to his stable platform. He found the fifth scout moving right to left at 160 yards. He tracked him, fired, and hit him in the leg. The scout went down but started crawling frantically.

Vandermir chambered another round, aimed with the cold precision of a man culling a herd, and fired again five down. The remaining scouts were in a full panic. They were watching their squad evaporate against an enemy who wasn’t missing. Vandermir fired at a sixth scout and missed. He rushed the shot, pulling it slightly left. It was his first error. He didn’t get frustrated.

He adjusted. He worked the bolt, settled the wood on the sandbag and fired again. The bullet struck the scout in the back. Six down, three remaining. The last three scouts managed to reach the tree line. Vandermir fired twice more into the shadows, but the heavy vegetation swallowed them. He couldn’t confirm the hits.

He stayed on the rifle, watching the jungle for another five minutes, waiting for movement. But there was nothing. The ghosts were gone. The entire engagement, from the first shot to the last, had taken eight minutes. Vandermir sat back in the mud. His hands were shaking violently now, not from fear, but from the massive adrenaline dump that hits you when the shooting stops.

He had just killed six men, possibly seven in less time than it took to drink a cup of coffee. Behind him he heard voices. The shooting had woken the entire perimeter. Soldiers were coming out of their positions, weapons ready, expecting a full scale assault. Sergeant Miller arrived first.

Miller was a stocky veteran from Pennsylvania, a man who had seen enough combat to know what a firefight sounded like. But he was confused. He had heard one rifle firing methodically, like a metronome. What the hell happened? Miller demanded, scanning the empty field. Japanese scouts. Vandermir said his voice sounded hollow, strange in his own ears. Nine of them got six confirmed. Maybe seven.

Miller stared at him. He looked at the empty field, then back at the private. At what range? Started at 180 yards, Vandermir replied. Last ones were maybe 160. Miller shook his head. Bullshit, he said flatly. Nobody hits at that range with open sights. Not like that. Vandermir didn’t argue.

He didn’t try to explain the physics or the platform. He simply pointed a trembling finger toward the kunai grass, where the morning light was illuminating the dark shapes of the fallen scouts. Miller raised his binoculars. He looked. He counted. He lowered the glasses slowly, his expression shifting from anger to shock. Jesus Christ, he whispered. In that moment, standing in the mud of Bougainville.

The sergeant realized two things. First, that Private Vandermir had just saved the platoon. And second, that whatever impossible thing Vandermir was holding in his hands, it had just rendered the official Army training manual obsolete. Victory in war usually brings medals. For Vandermir, it brought an investigation.

By 8:30 a.m., the legend of the Iowa Solution had spread through company K like wildfire. Men were crawling out of their foxholes just to look at the rifle. They saw the crude wooden platform, the scavenged aircraft aluminum, the wire ties. They saw the bodies in the grass, and they did the math.

Corporal Bill Henderson, the company scrounger, took one look at the rig and said, screw regulations. Can you make me one? By noon. Vandermir had seven requests. By evening, 15, he became a midnight manufacturer, turning the supply tent into a clandestine factory with Henderson sourcing the scrap materials. Vandermir built 20 platforms in two weeks. He didn’t ask for permission because he knew the answer would be no. And he was right.

The answer arrived on December 21st in the form of Captain Robert Thornton. Thornton was a West Point graduate, a man who believed that discipline was the backbone of the army and that uniformity was the backbone of discipline. He didn’t see innovation. He saw chaos. When Thornton conducted a surprise inspection and found 23 modified Springfields, he didn’t ask how well they worked. He didn’t ask how many lives they had saved.

He asked who was responsible. Sergeant Miller tried to intervene. He explained that Scout casualties had dropped dramatically since the men started using the Hay Racks. He tried to show the captain the data. Thornton didn’t care about data. He cared about the manual. This is unauthorized modification of government property, he declared. Direct violation of army regulations.

He ordered every single platform confiscated and destroyed. That evening, Vandermir stood by the fire pit and watched his work burn. He watched. The wood turned to ash and the aluminum struts melt and twist in the heat. It wasn’t just equipment burning. It was the safety of his friends. The consequences were immediate and lethal. Two days later, the ghost returned.

Japanese scouts, emboldened by the lack of long range fire, moved back into the 180 yard zone. Private First Class George Martinez from Texas was at the water point filling canteens. A single shot rang out from the tree line, 185 yards away. Martinez had been using a Hay Rack rifle before the confiscation. He was a good shot with it.

But on this day he was holding a standard issue weapon. He died before the medics could reach him. When Vandermir heard about Martinez, something in him snapped that night. He didn’t hide in the supply tent. He sat right in his foxhole and built another platform. He didn’t care about the court martial anymore.

He didn’t care about Leavenworth. Sergeant Miller found him the next morning and warned him. If the captain finds out, you’re done. Vandermir looked his sergeant in the eye and delivered the only argument that matters in war. It works, he said. Martinez is dead because we followed the rules. I’m not going to let anyone else die for a regulation. Miller looked at the private, then at the rifle.

He nodded slowly. Keep it hidden. During inspections, he said. I’ll do what I can. And just like that, the underground resistance began. Captain Thornton never realized that his men were disobeying him. But statistics have a way of surfacing the truth. By mid-January 1944, the underground factory was fully operational with 40 Hay Rack rifles back on the line.

And while Thornton was busy inspecting shoelaces, someone at Division headquarters was looking at the casualty reports and noticing a mathematical impossibility. The numbers were screaming. In early November 1943, before Vandermir picked up a piece of scrap wood. Company K was bleeding out at a rate of 4.2 casualties per week from Scout activity. These were men hit by long range fire. They couldn’t answer.

In late November and early December, after the Hay Rack was widely adopted, that number plummeted to 1.8. Even in January, despite Thornton’s attempt to crush it, the rate stayed low because the men were hiding the rifles by day and using them by night. Across the entire 148th Infantry Regiment, the shift was seismic.

Casualties dropped from 17.6 per week to just 6.3. That is a 64% reduction in sorrow. Conservative estimates suggest that Vandermir’s illegal invention prevented 130 casualties between November and March. 40 of those men would have been in coffins. Instead, they went home. But the most telling data didn’t come from American reports.

It came from the enemy. Captured Japanese intelligence from late 1943 revealed panic. A diary from a Japanese sergeant, translated later noted. Americans are shooting differently now. We cannot get close. Interrogation reports confirmed it.

A captured corporal told intelligence officers that forward observers were ordered to push their engagement distance back from 150 yards to 250 yards. When asked why, he gave a simple answer that validated every blister on Vandermir’s hands. Because they can kill us further than before. This anomaly finally drew the attention of Major Wilson from Division HQ. He arrived on February 8th, 1944.

Not to punish, but to learn. When Sergeant Miller handed him the crude, ugly contraption, Wilson didn’t recoil. He asked who designed it. Vandermir stepped forward. He explained the groundhogs. He explained the farm. Wilson turned the rifle over in his hands. He looked at the rough pine, the stolen aluminum, the wire ties. Then he looked at the casualty reports.

Captain Thornton ordered these destroyed. Vandermir admitted, expecting the handcuffs. He said it was an unauthorized modification of government property. Major Wilson looked at the private, then at the rifle that had saved 100 lives. Captain Thornton is technically correct, Wilson said, but he’s also an idiot.

Keep building them. I’ll handle the paperwork. Major Wilson was a man of his word, but the U.S. Army moves at the speed of a glacier. It took three months of bureaucracy, testing and reports before the Hay Rack was officially recognized. In May 1944, the Army Ground Forces Equipment Board finally released their findings.

Their conclusion was a sterile, typed sentence that validated a desperate midnight idea. The stability platform demonstrates significant improvement in practical accuracy at ranges exceeding 150 yards. By June, the Army authorized the modification. Supply sergeants across the Pacific were issued instructions on how to build them.

By August, over 800 modified Springfields were hunting in the jungle. By the end of the war, that number topped 2000. But if you look at the official documents, you won’t find the name Raymond Vandermir. The Army called it a field development. They gave no credit to the farm boy who risked prison to build it.

And Vandermir, he didn’t care. He didn’t want a medal. He wanted his friends to survive. After the war, he went back to Sioux City, married his high school sweetheart, Eleanor, and spent the next 43 years doing exactly what he did before the world caught fire. Growing corn and soybeans, he rarely spoke about the war.

The original Hay Rack, the one that killed six scouts in ten minutes, hung in his workshop, gathering dust above a workbench. He used it occasionally to shoot groundhogs just to keep his eye in. In 1987, a historian finally tracked him down. He told Vandermir that his invention was credited with saving approximately 200 American lives.

He asked if it bothered him that he never got the credit. Vandermir. His answer was the epitaph of a true professional. I didn’t do it for recognition, he said. I did it because Fletcher and Martinez and Whitaker deserved better than dying to scouts. They couldn’t see. Raymond Vandermir died in 1989. His obituary listed him as a farmer and a grandfather.

It didn’t mention that he single handedly changed sniper doctrine in the Pacific theater. But the lesson of the Hay Rack isn’t about rifles. It’s about where real innovation comes from. It rarely comes from the top down. It doesn’t come from committees or generals or well-funded research labs. It comes from the guys in the mud. It comes from the people who are suffering the consequences of bad design and decide to fix it themselves.

War doesn’t wait for authorization. Men die while paperwork circulates. The Hay Rack worked because one man had the skill to see a solution, and the courage to ignore the regulations that stood in his way. Sometimes to do the right thing. You have to break the rules. And sometimes the only thing standing between you and a ghost is a piece of scrap wood and the will to use it.

News

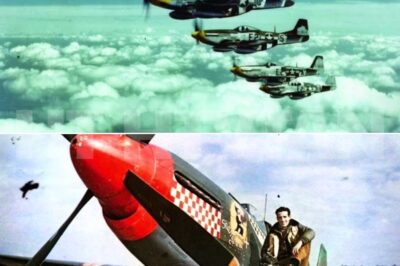

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

CH2 . America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped as North Korean fighters strafe the runway, destroying transports one by one. Enemy armor is twenty miles away and closing. North Korean radar picks up five unidentified contacts approaching from the sea. The flight leader squints through his La-7 canopy.

America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped…

CH2 . Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above Cape Bon, Tunisia.

Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above…

CH2 . Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles northwest of Lelay, New Guinea. The oil blackened hand trembled as a Japanese naval officer gripped the splintered remains of what had once been part of the destroyer Arashio’s bridge structure. His uniform soaked with fuel oil and seaater, recording in his mind words that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles…

CH2 . Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on April 18th, 1942 fundamentally altered the Pacific Wars trajectory, forcing Japan into a defensive posture that would ultimately contribute to its defeat.

Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on…

CH2 . German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of December 1944, the German war machine, a beast long thought to be dying, had roared back to life with a horrifying final fury. Hitler’s last desperate gamble, the massive Arden offensive, known to history as the Battle of the Bulge, had ripped a massive bleeding hole in the American lines.

German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of…

End of content

No more pages to load