The Bl@ck Man Who Grabbed a Machine G.u.n And Became Pearl Harbor’s Unlikely Hero…

December 7th, 1941. Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Approximately 7:55 a.m. The morning was calm. The kind of stillness sailors cherished before duty called, the sun climbed slow and golden over the harbor, glinting off the steel hulls of the Pacific Fleet, anchored in the shallow blue water. On the deck of the USS West Virginia, mess attendant Doris Dory Miller wiped his hands on a towel. his mind already turning to breakfast service, the scent of coffee mixed with sea air. A few jokes passed among the galley crew, laughter light, unguarded, unaware that history was seconds away from tearing through the sky. Then a shriek, not human, but mechanical, the distant whale of sirens, followed by the staccato rattle of machine gunfire.

Someone shouted from the deck, “Air raid! This is not a drill!” Miller’s head snapped up over battleship row. Dark shapes plunged from the morning light. Silver wings flashing red suns. The first explosion struck the Arizona, a deafening roar that shook the air itself. The deck under Miller’s feet quivered like a struck drum.

He ran toward the hatch, heart hammering. Another blast closer this time, sent a column of fire clawing skyward. By the time Miller reached top side, the West Virginia was already hit. A torpedo slammed into her port side, throwing him against a bulkhead. Smoke and heat poured across the deck as sailors scrambled for battle stations.

Men screamed for medics. The air stank of oil and cordite. He looked around, searching for orders. His assigned duty. Laundry, meals, cleanup meant little now. On the bridge, Captain Mvin Benian was struck down by shrapnel, bleeding but refusing to leave his post. Around Miller, chaos consumed everything. He spotted a sailor beside an unattended50 caliber Browning anti-aircraft gun.

The man lay motionless, smoke curling around the weapon. Miller hesitated. He’d never been trained to fire a machine gun. Navy policy didn’t allow it. Black sailors were cooks, cleaners, attendants, never gunners. But the sky didn’t care about policy. Another bomb screamed in. Miller ducked instinctively, the explosion hurling shrapnel across the deck.

When he rose, his jaw clenched. The gun sat unmanned. Aimed at the swarm above. He climbed behind it. The metal was hot under his hands. He gripped the handles, pressed the trigger, and the gun roared to life. Tracer rounds stitched through the sky. He didn’t aim by training, only by instinct and rage.

The recoil pounded his shoulders. The air filled with a rhythm of defiance. Planes dove low, their engines howling. Miller tracked one, fired, saw it veer, smoke trailing, plunging toward the water. Then another, the other gunners cheered between reloads, disbelief mixing with adrenaline. For a few breathless minutes, amid fire and ruin, Dory Miller, a man never meant to touch a weapon, became the ship’s defender.

and no one on that deck could have predicted what he would do next. Months before the attack, the Navy had classified Miller as mess attendant third class. Born in Waco, Texas in 1919, he was the son of sharecroppers. Football had been his passion, his size and strength unmatched. But opportunity had a ceiling for a young black man in 1930s Texas.

The Navy offered steady pay and a chance to see the world. Yet, even at sea, segregation followed him. On ships like the West Virginia, black sailors weren’t permitted to handle weapons, serve in combat roles, or even train for them. They cleaned officers’ quarters, prepared meals, carried laundry, and shined shoes.

The official reasoning was tradition. The truth was racism carved deep into policy. When Miller enlisted in 1939, he accepted the uniform with pride, but it came with humiliation stitched into every seam. He’d often overhear white sailors joke that the only battle a colored messman might win was against dirty dishes. He laughed along sometimes, not out of agreement, but survival.

There was a code among black sailors. Keep your head down, work twice as hard, and maybe someday you’d be seen. By 1941, Miller had earned a reputation as dependable, strong, and steady. He stood 6′ three and weighed over 200 lb, a gentle giant with quiet discipline. Among the mess crew, he was Dory, a nickname softened by friendship.

But behind that calm exterior was a man who wondered if courage meant anything when no one allowed you to show it. That morning, when the sirens wailed and the first explosions rolled across the harbor, Miller’s world shifted from order to chaos, the hierarchy that had defined his service. White officers above, black attendants below, burned away in the flames.

He no longer saw rank, only survival. The same Navy that had told him he wasn’t fit to fight now demanded every man to fight, trained or not. Below deck, water poured through ruptured hull plates. Men screamed in darkness. Miller helped drag wounded sailors to safety, carrying them like sacks of grain up ladders slick with oil. The heat was suffocating.

He could feel the ship lifting beneath his feet. Still, he kept moving, pulling, lifting until his muscles trembled. When he reached the main deck again, breath ragged, his eyes found that unmanned gun. And in that instant, the lines of race and rank meant nothing. The United States Navy had refused to teach him to fight, so he would teach himself.

The sky over Pearl Harbor was a storm of smoke and steel. Japanese planes attacked in waves. First the torpedo bombers, then the dive bombers, and then the fighters strafing the decks. The West Virginia took at least seven torpedoes. Fires spread across the port side, licking the superructure. Men threw ammunition overboard to keep it from exploding.

Miller’s hands blistered as he gripped the Browning’s handles. Each burst rattled his body. The air filled with a deafening thud of anti-aircraft guns from neighboring ships. Tennessee, Oklahoma, Arizona. The harbor itself was boiling, black with burning oil. A Japanese plane roared overhead, strafing the deck. Miller ducked behind the gun’s shield as bullets pinged against the metal.

He rose again, firing back. Another sailor joined him to feed ammunition belts. They worked in rhythm. Shout, reload, fire, a dance of survival under falling bombs. In those minutes, Miller’s world narrowed to the crosshairs before him. The fear that had shadowed his service, the quiet shame of being underestimated, was gone.

Every trigger pull was an answer to years of mockery. He wasn’t supposed to be here, wasn’t supposed to be fighting. Yet here he was, standing tall against the Empire that had just declared war. Through smoke, he spotted another bomber banking low toward battleship row. He tracked it, squeezed, the gun kicked, and he saw it burst into flame.

The deck erupted in cheers, even as another blast rocked them off balance. Captain Benian still lay near the bridge, bleeding out when orders came to abandon ship. Miller refused to go without helping him. He and several others carried the wounded captain toward a safer position, but Benian insisted, “Leave me. Save yourselves. Miller stayed until forced to retreat.

The fires grew too fierce. Ammunition cooked off in the heat. Miller’s clothes were singed, face stre with sweat and soot. Only when the deck began to buckle did he leap into the harbor, swimming through burning oil to reach shore. Behind him, the West Virginia settled into the mud. Her proud hull dying in slow agony.

Hours later, the harbor smoldered. Arizona’s wreck still burning. Oklahoma capsized. West Virginia half sunken but defiant. Over 2,400 Americans were dead. Among the survivors, rumors began to spread. Someone on West Virginia, a mess attendant, had taken control of a machine gun and fought like a veteran. At first, few believed it.

Black sailors weren’t trained for that, but witness after witness confirmed it. Miller had shot down at least two enemy aircraft, possibly more. Commander Benian, before dying, had ordered the man’s name be noted for bravery. It was a rare thing. A black man’s valor forced onto the official record. In the days after, Miller went about his duties quietly.

He didn’t boast. When officers asked how he done it, he shrugged. It was just what I had to do, sir. For him, it wasn’t heroism. It was instinct, duty, humanity. News spread across the fleet, then the nation. The press seized on the story of the negro messman who manned a gun. Yet early reports didn’t even mention his name.

He was simply an unnamed colored sailor. It took the Navy weeks to identify him publicly. When they finally did, Doris Dory Miller became the first black American hero of World War II. His image appeared on posters, newspapers, and speeches calling for equality. To many, he symbolized a contradiction too big to ignore.

A man the Navy had deemed unfit for combat, had become its first hero of the Pacific War. For a brief moment, America celebrated him. He was awarded the Navy Cross by Admiral Chester W. Nimmitz, the highest decoration for valor ever given to a black sailor at that time. Nimttz pinned the medal to Miller’s chest aboard the Enterprise, saying, “This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race.

” Miller stood stiffly at attention, eyes forward, cameras flashed. But beneath the applause, the Navy segregation policy remained untouched. The same institution that decorated him still barred black sailors from combat duty. When the ceremony ended, he returned not to a gun station, but to laundry detail. Across the country, black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier and Chicago Defender rallied behind him, demanding full integration of the armed forces.

They called him proof, living undeniable proof. The courage had no color. He toured briefly to promote war bonds, speaking in small towns and naval bases. Crowds cheered, but behind the cheers was the uneasy truth. America could celebrate a black hero, but not yet serve beside him as an equal. Miller never complained publicly.

When reporters asked if he wanted to keep fighting, he said, “It’s my job. I’ll do whatever they ask of me.” In 1943, he was assigned to the escort carrier Lisscom Bay in the Pacific. On November 24th, during operations near the Gilbert Islands, a Japanese torpedo struck the ship’s magazine. The explosion tore through the carrier.

She sank in minutes. Of the 900 aboard, over 600 were lost. Dory Miller was among them. His body was never recovered. The war moved on. Names faded amid the noise of new battles. Guadal Canal, Tarawa, Normandy. But for those who remembered Pearl Harbor, Dory Miller’s name carried weight.

In 1944, a destroyer escort was commissioned in his honor, the USS Miller. It was the first US Navy ship named after an African-American hero. Still, deeper recognition lagged. While white officers from that day received medals and promotions, Miller’s bravery was remembered mostly in the black press, not official history. The nation moved toward victory, but not equality.

Decades later, historians revisited the morning of December 7th. Witness accounts were verified, his actions confirmed beyond doubt. In 2020, the Navy announced that a new aircraft carrier, the USS Doris Miller, would bear his name. It would be the first super carrier named after an enlisted sailor and the first after an African-Amean.

For the Navy that once told him he couldn’t fight, it was a reckoning long overdue. He never lived to see the metal, never saw his name carved into steel or taught in classrooms. But the story of that morning, the quiet man who picked up a gun he wasn’t supposed to touch and changed what America believed a black man could do endures.

News

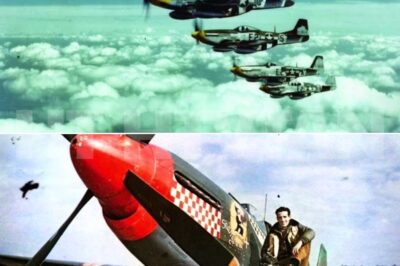

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

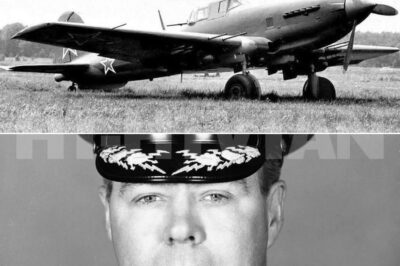

CH2 . America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped as North Korean fighters strafe the runway, destroying transports one by one. Enemy armor is twenty miles away and closing. North Korean radar picks up five unidentified contacts approaching from the sea. The flight leader squints through his La-7 canopy.

America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped…

CH2 . Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above Cape Bon, Tunisia.

Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above…

CH2 . Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles northwest of Lelay, New Guinea. The oil blackened hand trembled as a Japanese naval officer gripped the splintered remains of what had once been part of the destroyer Arashio’s bridge structure. His uniform soaked with fuel oil and seaater, recording in his mind words that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles…

CH2 . Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on April 18th, 1942 fundamentally altered the Pacific Wars trajectory, forcing Japan into a defensive posture that would ultimately contribute to its defeat.

Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on…

CH2 . German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of December 1944, the German war machine, a beast long thought to be dying, had roared back to life with a horrifying final fury. Hitler’s last desperate gamble, the massive Arden offensive, known to history as the Battle of the Bulge, had ripped a massive bleeding hole in the American lines.

German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of…

End of content

No more pages to load