Starving German POWs Couldn’t Believe What Americans Served Them for Breakfast…

May 17th, 1943, Northern England. Cold mist hung low over the railard, wrapping the countryside in a damp, gray silence. The cattle cars hissed as steam curled from beneath their iron wheels. Inside, 180 German soldiers waited, cramped and sleepless after 3 days of transport from the ports of Liverpool.

The air smelled of rust, rain, and human exhaustion. When the doors finally slid open, Corporal Deer Weiss, a 24, blinked against the morning light. His once proud Vermached uniform was stre with mud. His belt loosened, his face hollow from hunger. For months his unit had fought in Tunisia, proud defenders of the Africa corps until British armor crushed them outside Cap Bon.

Now the same British soldiers stood before him again. This time not as enemies on a battlefield, but as guards in khaki great coats. Their rifle slung with quiet precision. Rouse Schnell came the bark, not from a German, but in carefully rehearsed English accented German. Formlines, no running, no shouting.

Deer stepped down onto wet gravel. A chill went through his boots. He expected kicks, curses, maybe rifle butts to the ribs. Berlin’s radio broadcasts had warned them. The British hate you. They will starve you. They will work you until you die. Every captured man had heard those same grim words. But here in the damp calm of Northern England, something was different.

There was no shouting, no violence. The British sergeant, a thick-sh shouldered man with rain dripping from his cap, simply raised a clipboard and pointed. You’ll be searched. Then fed. Follow the white line. Fed. The word hit like a distant echo of normal life. Deer hadn’t eaten properly in days. The last ration issued before capture had been a crust of bread shared between three men.

He followed the white line painted on the gravel to a small canvas tent where British privates checked pockets and belts. The search was efficient but almost polite. One guard removed a small photograph from deer’s breast pocket. A faded picture of a woman smiling in sunlight. Instead of tossing it away, the guard carefully placed it back into his tunic.

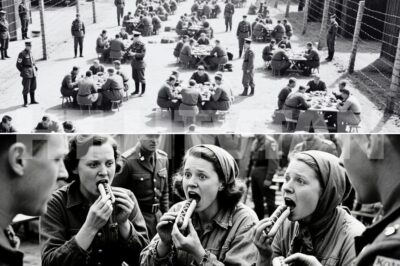

Inside the camp gates, rows of wooden huts stood neat and orderly behind barbed wire. Smoke rose from a brick chimney at the far end. The kitchen, he guessed. The smell made his stomach clench painfully. Cooked oats and tea. They were lined up outside a barracks marked processing. British officers checked their names, assigned them prisoner numbers, and handed each a tin cup and plate.

The entire operation felt more like a railway station than a prison. When deer finally reached the mess hut, he froze. A long table ran down the center, and behind it stood two British cooks, sleeves rolled to their elbows, ladelling something thick and steaming from iron pots. “Next,” called one. The prisoner ahead of him, an older sergeant from Bremen, received a ladle of porridge, a slice of bread, and a cup of tea so dark it looked like tar.

“When his turn came, deer hesitated, unsure if it was a trick.” “Go on, lad,” said the cook, motioning with his ladle. “It won’t bite.” The warmth of the bowl stung his cold hands. The smell was simple but overwhelming. Oats, sugar, something that reminded him of his mother’s kitchen before the war. He took a tentative spoonful. It was bland.

British food, no doubt, but it was hot. Real food. After weeks of salt biscuits and cold rations, it tasted like a miracle. He swallowed again, slower this time. Around him, other prisoners ate in silence, not out of fear, but disbelief. Some blinked back tears. Others simply stared at their bowls as if trying to understand how the enemy could feed them.

Across the room, a British corporal leaned against a post, sipping his own mug of tea. His uniform was soaked through, but his posture was relaxed, calm. He wasn’t sneering or gloating. He looked professional, almost bored. When he caught deer’s eye, he nodded once, a small human gesture, then he turned away. The silence inside the messaul was broken only by the clink of spoons.

For the first time since capture, deer felt something he hadn’t expected. Safety. After breakfast, they were marched to medical inspection. A young British nurse, her sleeves rolled neatly above the elbow, examined his frostbitten fingers, and scribbled notes in perfect handwriting. She didn’t look at him like an animal or an enemy, just another patient in need of care.

“Drink plenty of water,” she said gently. Her accent was soft southern English. Deer didn’t understand every word, but the tone was unmistakable, calm, almost kind. He nodded mutely, unsure how to respond. The propaganda had never prepared him for kindness. Later that morning, when the prisoners were assigned to barracks, he found himself with men from across the shattered remnants of the Africa Corps.

Someone joked bitterly that they’d been captured by gentlemen. Another muttered that it was all an illusion, that the real torture would come later. But as the hours passed, the illusion didn’t fade. They were allowed to rest. They were given blankets. The guards kept their distance, watching, but not menacing. Outside, the English rain drumed steadily on the tin roofs, not the sound of fear, but of a strange foreign piece.

That night, lying on a real mattress for the first time in months, deer stared up at the wooden ceiling. He thought about the breakfast in that plain bowl of porridge, and the way it had changed something inside him. It wasn’t just food. It was proof that everything he’d been told about these people might have been a lie.

He thought of his mother’s letter before deployment, the one that said, “Remember, my son, not all enemies are evil, and not all friends are good.” At the time, he’d laughed. Now he wasn’t so sure. Outside, a British guard walked past his boots, crunching in gravel. A flashlight beam swept across the bareric window, then vanished.

For the first time in months, deer closed his eyes and slept without fear. The fog that clung to the camp that morning seemed lighter somehow. Not quite as cold, not quite as gray. The war still raged across Europe, but inside Camp 198 in Northern England, time moved differently. Here, behind barbed wire and wooden fences, a strange rhythm had taken hold.

Part military discipline, part quiet survival. It had been over two weeks since Corporal Deer Weiss had first stepped into the British camp, exhausted and starved from North Africa. In that short time, his body had begun to mend, but it was his mind that struggled the most. Every day began the same.

the whistle at dawn, boots on gravel, rows of men standing at attention before the Union Jack fluttering from the pole. British guards called out names, checked headcounts, and handed out daily orders. And then came breakfast. No one ever forgot the first meal, the steaming bowl of oats, the sweet tea, the slice of warm bread. It had stunned every German soldier in line.

But as days passed, that breakfast became something more. It became ritual, a reminder that even prisoners were still men. That morning, deer woke before the whistle. The barracks were quiet except for the creek of old wood and the steady breathing of 80 sleeping men. He sat up slowly, rubbed his eyes, and looked out the small window. The horizon glowed pale blue.

Across the yard, smoke already rose from the kitchen chimney, and with it that unmistakable smell, porridge and toast. He smiled faintly, almost against his will. The British and their oats, he murmured. His bunkmate, Hans Keller, an older man from Munich with a mechanic’s hands, groaned awake. Do you ever wonder? Hans muttered.

If they’re fattening us for something, deer smirked. If they are, I’ll thank them for it. Better than starving under Raml’s sun. Hans laughed quietly, then fell silent. It’s strange, isn’t it? The enemy feeding us like guests. Deer didn’t answer right away. His gaze drifted to the corner of the barracks where someone had hung a small drawing, charcoal sketches of home, rooftops, a woman’s face, a church spire…

To be continued in C0mments ![]()

May 17th, 1943, Northern England. Cold mist hung low over the railard, wrapping the countryside in a damp, gray silence. The cattle cars hissed as steam curled from beneath their iron wheels. Inside, 180 German soldiers waited, cramped and sleepless after 3 days of transport from the ports of Liverpool.

The air smelled of rust, rain, and human exhaustion. When the doors finally slid open, Corporal Deer Weiss, a 24, blinked against the morning light. His once proud Vermached uniform was stre with mud. His belt loosened, his face hollow from hunger. For months his unit had fought in Tunisia, proud defenders of the Africa corps until British armor crushed them outside Cap Bon.

Now the same British soldiers stood before him again. This time not as enemies on a battlefield, but as guards in khaki great coats. Their rifle slung with quiet precision. Rouse Schnell came the bark, not from a German, but in carefully rehearsed English accented German. Formlines, no running, no shouting.

Deer stepped down onto wet gravel. A chill went through his boots. He expected kicks, curses, maybe rifle butts to the ribs. Berlin’s radio broadcasts had warned them. The British hate you. They will starve you. They will work you until you die. Every captured man had heard those same grim words. But here in the damp calm of Northern England, something was different.

There was no shouting, no violence. The British sergeant, a thick-sh shouldered man with rain dripping from his cap, simply raised a clipboard and pointed. You’ll be searched. Then fed. Follow the white line. Fed. The word hit like a distant echo of normal life. Deer hadn’t eaten properly in days. The last ration issued before capture had been a crust of bread shared between three men.

He followed the white line painted on the gravel to a small canvas tent where British privates checked pockets and belts. The search was efficient but almost polite. One guard removed a small photograph from deer’s breast pocket. A faded picture of a woman smiling in sunlight. Instead of tossing it away, the guard carefully placed it back into his tunic.

Inside the camp gates, rows of wooden huts stood neat and orderly behind barbed wire. Smoke rose from a brick chimney at the far end. The kitchen, he guessed. The smell made his stomach clench painfully. Cooked oats and tea. They were lined up outside a barracks marked processing. British officers checked their names, assigned them prisoner numbers, and handed each a tin cup and plate.

The entire operation felt more like a railway station than a prison. When deer finally reached the mess hut, he froze. A long table ran down the center, and behind it stood two British cooks, sleeves rolled to their elbows, ladelling something thick and steaming from iron pots. “Next,” called one. The prisoner ahead of him, an older sergeant from Bremen, received a ladle of porridge, a slice of bread, and a cup of tea so dark it looked like tar.

“When his turn came, deer hesitated, unsure if it was a trick.” “Go on, lad,” said the cook, motioning with his ladle. “It won’t bite.” The warmth of the bowl stung his cold hands. The smell was simple but overwhelming. Oats, sugar, something that reminded him of his mother’s kitchen before the war. He took a tentative spoonful. It was bland.

British food, no doubt, but it was hot. Real food. After weeks of salt biscuits and cold rations, it tasted like a miracle. He swallowed again, slower this time. Around him, other prisoners ate in silence, not out of fear, but disbelief. Some blinked back tears. Others simply stared at their bowls as if trying to understand how the enemy could feed them.

Across the room, a British corporal leaned against a post, sipping his own mug of tea. His uniform was soaked through, but his posture was relaxed, calm. He wasn’t sneering or gloating. He looked professional, almost bored. When he caught deer’s eye, he nodded once, a small human gesture, then he turned away. The silence inside the messaul was broken only by the clink of spoons.

For the first time since capture, deer felt something he hadn’t expected. Safety. After breakfast, they were marched to medical inspection. A young British nurse, her sleeves rolled neatly above the elbow, examined his frostbitten fingers, and scribbled notes in perfect handwriting. She didn’t look at him like an animal or an enemy, just another patient in need of care.

“Drink plenty of water,” she said gently. Her accent was soft southern English. Deer didn’t understand every word, but the tone was unmistakable, calm, almost kind. He nodded mutely, unsure how to respond. The propaganda had never prepared him for kindness. Later that morning, when the prisoners were assigned to barracks, he found himself with men from across the shattered remnants of the Africa Corps.

Someone joked bitterly that they’d been captured by gentlemen. Another muttered that it was all an illusion, that the real torture would come later. But as the hours passed, the illusion didn’t fade. They were allowed to rest. They were given blankets. The guards kept their distance, watching, but not menacing. Outside, the English rain drumed steadily on the tin roofs, not the sound of fear, but of a strange foreign piece.

That night, lying on a real mattress for the first time in months, deer stared up at the wooden ceiling. He thought about the breakfast in that plain bowl of porridge, and the way it had changed something inside him. It wasn’t just food. It was proof that everything he’d been told about these people might have been a lie.

He thought of his mother’s letter before deployment, the one that said, “Remember, my son, not all enemies are evil, and not all friends are good.” At the time, he’d laughed. Now he wasn’t so sure. Outside, a British guard walked past his boots, crunching in gravel. A flashlight beam swept across the bareric window, then vanished.

For the first time in months, deer closed his eyes and slept without fear. The fog that clung to the camp that morning seemed lighter somehow. Not quite as cold, not quite as gray. The war still raged across Europe, but inside Camp 198 in Northern England, time moved differently. Here, behind barbed wire and wooden fences, a strange rhythm had taken hold.

Part military discipline, part quiet survival. It had been over two weeks since Corporal Deer Weiss had first stepped into the British camp, exhausted and starved from North Africa. In that short time, his body had begun to mend, but it was his mind that struggled the most. Every day began the same.

the whistle at dawn, boots on gravel, rows of men standing at attention before the Union Jack fluttering from the pole. British guards called out names, checked headcounts, and handed out daily orders. And then came breakfast. No one ever forgot the first meal, the steaming bowl of oats, the sweet tea, the slice of warm bread. It had stunned every German soldier in line.

But as days passed, that breakfast became something more. It became ritual, a reminder that even prisoners were still men. That morning, deer woke before the whistle. The barracks were quiet except for the creek of old wood and the steady breathing of 80 sleeping men. He sat up slowly, rubbed his eyes, and looked out the small window. The horizon glowed pale blue.

Across the yard, smoke already rose from the kitchen chimney, and with it that unmistakable smell, porridge and toast. He smiled faintly, almost against his will. The British and their oats, he murmured. His bunkmate, Hans Keller, an older man from Munich with a mechanic’s hands, groaned awake. Do you ever wonder? Hans muttered.

If they’re fattening us for something, deer smirked. If they are, I’ll thank them for it. Better than starving under Raml’s sun. Hans laughed quietly, then fell silent. It’s strange, isn’t it? The enemy feeding us like guests. Deer didn’t answer right away. His gaze drifted to the corner of the barracks where someone had hung a small drawing, charcoal sketches of home, rooftops, a woman’s face, a church spire.

They were drawn on scraps of British newspaper, hope trapped behind wire. Outside they lined up for inspection. Rain had turned the yard into soft mud, and the British guards stood in their slick coats steaming mugs in hand. The same corporal from the first day, Sergeant Collins, tall weathered with that constant calm, walked the line.

He stopped in front of Deer and Hans. “Morning, lads,” he said, voice steady. “No trouble in the barrack.” Deer shook his head. “No, sir.” Collins nodded. “Good. Kitchen’s open. Eat well. Work details light today.” “Light?” That word meant everything. It meant no digging, no hauling coal, just simple camp labor, maintenance, cleaning, gardening.

Enough to pass time, but not enough to break a man. When they reached the mess hall, the routine felt strangely comforting now. Tin plate, ladle of porridge, slice of bread, hot tea with sugar, and always with sugar. Some prisoners joked that the British used it to sweeten the enemy.

But behind the jokes, gratitude simmerred. That morning, though, something new happened. As they ate, one of the kitchen staff, a young British private named Thomas Briggs, began playing a small harmonica near the stove. A quiet soft tune, something Irish, haunting but gentle. The sound filled the messaul, mingling with the scrape of spoons and the low murmur of conversation.

For a moment, everyone stopped eating. Even the guards glanced up. Music. Real music in a prison. When Briggs noticed the attention, he hesitated. But the British sergeant nodded for him to continue. The melody deepened, simple but beautiful. Deer felt something stir in his chest. Memories of his sister’s piano. Laughter around the dinner table.

Things buried under dust and gunpowder. When the tune ended, someone at the back, a German private with a cracked voice, softly began to humiliene. At first, no one joined. Then another voice. Then another. Within seconds, the entire hall was humming the song. That strange universal wartime melody known by both sides.

The British didn’t stop them. They just listened. And as that chorus of weary German prisoners filled the air, the war outside the fence seemed to fade, if only for a few minutes. After breakfast, the men were split into groups. Deer and Hans were assigned to garden duty, clearing weeds near the officer’s hut.

The work was slow, but the freedom to move, to breathe fresh air was priceless. Sergeant Collins approached, kneeling beside them. “You men did a fine job last week,” he said, inspecting the soil. “Keep at it, and you might earn camp credit. Small privileges.” Deer looked up cautiously. “Privileges?” Collins nodded. “Library hours? Extra mail? Maybe a football match if weather allows.

A football match?” The idea seemed absurd. Yet a spark lit in the men’s faces. When Collins left, Hans grinned. The British treat us like school boys. Deer shook his head slowly. No, like men. That’s the difference. That evening, after supper, the prisoners gathered quietly by the fence. Beyond the barbed wire, the sunset painted the English fields gold.

Somewhere in the distance, a train whistled. It sounded free. A few guards smoked by the gate, chatting casually. No one shouted. No one aimed rifles. It struck deer that the camp was built not on fear but on rules and respect. Even the barbed wire felt them symbolic. The war inside the fence was already ending, at least for them, he turned to Hans.

When this is over, Deer said quietly. I’ll never forget this breakfast. Hans chuckled. You’ll remember porridge for the rest of your life. Deer smiled faintly. Not the food, the message. They wanted us to see something. Hans frowned. And what’s that? That mercy still exists even in war. They stood in silence as the last light faded.

Inside the barracks, someone began softly whistling the same tune Briggs had played that morning. One by one, the men joined in, humming under their breath. No guns, no propaganda, no hatred, just the quiet sound of men rediscovering their humanity, one breakfast at a time. July 1st, 1943. Camp 198 North Yorkshire.

The summer rain had finally eased. Dew shimmerred on the barbed wire like strings of glass. Somewhere beyond the fence, a lark sang above the empty fields, the kind of sound that reminded the prisoners of home, of mornings before uniforms and orders and surrender. For Corporal Der Vice, the war had become a memory blurred by routine.

He rose at dawn, washed in the cold basin, folded his blanket with precision, and waited for the whistle. The camp had changed in those weeks, or perhaps the men had. They no longer looked like the beaten ghosts who had stumbled off trains in May. Faces were fuller, eyes clearer, movement steadier. Hunger no longer ruled every thought. That morning, as the prisoners lined up for roll call, there was a different kind of buzz among them.

Quiet murmurss exchanged glances. A British guard had announced the night before that a mail delivery from Germany had arrived. For many, it would be the first word from home in months, maybe years. When Sergeant Collins walked down the line, he carried a small canvas bag bulging with envelopes. He began calling names one by one in his steady Yorkshire voice.

Krueger Ernst Huffman Carr, Kella Hans. Hun stepped forward, hands trembling, eyes wide. He hadn’t heard from Munich since Christmas of 1942. He took the letter carefully like a relic and stared at the familiar handwriting before retreating silently back to his spot. Then came the name Vice Deer. Deer’s chest tightened. He stepped forward, his boots heavy in the mud.

Collins handed him a thin brown envelope, the edges worn, the ink slightly smudged by travel. The return address read Berlin, his mother’s hand. He recognized it instantly. For a moment, the world around him faded, and the fences, the guards, the drizzle, all of it. Only that small piece of paper mattered now. Later, after breakfast, porridge, bread, tea, the usual, deer sat on the edge of his bunk.

Around him, men were opening letters, crying, laughing, some reading aloud, others unable to speak at all. He turned the envelope in his hands. The paper was thin, already soft from the moisture of his fingers. Finally, he tore it open. My dear deer, your father listens to the radio every night hoping for news from Africa.

When word came that your unit had been taken prisoner, he did not speak for 3 days. But then the neighbors told us the British treat prisoners with decency. I pray that is true. Eat, my son. Sleep. The war will end one day, and when it does, I want you home with both hands and both feet. Your sister Anna has started working at the rail depot.

She says she will learn English just to write to you one day. We have little here now in bread is rationed and sugar is gone. But we light a candle every Sunday and think of you. Remember this always. You are not forgotten and you are still loved. Mother deer folded the letter carefully, pressing it to his chest. His throat tightened.

The world outside might be burning, but inside this camp, he had just heard the voice of home again. Hans looked up from his own letter, eyes glassy but smiling. Good news. Deer nodded. They’re alive. Hungry but alive. Hans exhaled in relief. Mine says the same. Munich’s been bombed again, but they’re safe. My wife says she still keeps my uniform pressed. Foolish woman.

They both laughed quietly. The sound like a release of months of weight. That afternoon, the prisoners were given something new. Extra rations of jam. Strawberry British made thick and sweet. A small celebration, Collins explained, to mark the arrival of the male. In the messaul, deer spread the jam onto his bread, watching the red color soak into the crust.

Around him, conversations flowed in low, steady voices, fragments of home of memories of human warmth. A British nurse, Lieutenant Mary Harrington, entered the hall, carrying a clipboard. She had become a familiar figure in the camp’s medical hut, tending wounds and fevers with quiet precision. She noticed the jam, smiled faintly, and said, “So, the post finally reached you lot.

” “About time.” Deer looked up, unsure if he was allowed to reply. But she continued, “My brother’s a prisoner, too,” she said softly. “In Italy. I wonder if someone there is giving him breakfast right now.” Her voice carried no malice and only weary humanity. For a long moment, deer stared at her, trying to reconcile the idea that this woman, this nurse feeding her country’s enemies, also carried the same pain, the same waiting as his own mother back home. He found his voice.

“If he is,” Deer said quietly, “I hope they treat him as you’ve treated us.” She met his eyes and smiled faintly. “That’s the point, isn’t it? Someone has to start being human again.” And with that, she turned and walked out, the sound of her boots fading down the corridor. The days that followed carried a new kind of energy.

Some prisoners began teaching English lessons using scraps of newspapers. Others played football in the yard with a rag stuffed ball the British had given them. Evenings were filled with laughter again, low, cautious, but real. But it wasn’t peace. It was something deeper, understanding. One night, as the men gathered near the fence, a storm rolled over the moors.

Rain hammered against the tin roofs, thunder echoing across the valley. The guards huddled under their posts, coats pulled tight while prisoners stayed awake, talking quietly in the dim lantern light. Hans leaned toward Deer. Do you ever wonder, he said, “What will happen when this ends?” Deer stared into the darkness beyond the wire. “If we go home,” he said slowly.

“How do we tell them this? That the enemy showed mercy? They won’t believe it.” Hans nodded grimly. They’ll call us liars or worse. Maybe, deer said, but I’ll still tell it. The thunder cracked above, shaking the bareric walls. A British guard ran past, laughing as the rain soaked him through.

The absurdity of it all, soldiers and prisoners trapped under the same storm. Both just men trying to survive, struck deer with quiet awe. He whispered almost to himself, “War makes monsters out of men.” And then kindness reminds them they were human all along. A week later, a notice appeared on the camp board. Volunteers needed for local farm work, paid in extra rations.

It was another shock. Prisoners working freely outside the wire under British supervision. Many stepped forward, eager for the change of scenery. Deer and Hans joined them. The next morning, they were marched to a nearby farm under light guard. The air smelled of hay and wet earth. The farmer’s wife brought tea in tin cups, real tea with milk, and smiled awkwardly at the prisoners.

“Work hard, boys,” she said. “The cows don’t care what flag you fought for.” By evening, when they returned to camp, the guards didn’t need to shout or push. They walked together, weary but oddly content. Something invisible had shifted, a kind of fragile peace growing in the shadow of war. That night, as deer read his mother’s letter again by lantern light, the nurse’s words echoed in his mind.

Someone has to start being human again. And for the first time since the war began, he truly believed it might be possible. The war was finally over. Germany had surrendered. Europe was silent again. A silence heavy with loss, with ghosts, with rebuilding. And in the rolling green hills of North Yorkshire, behind the fences of Camp 198, that silence felt both like freedom and like an ending no one had prepared for.

The morning mist clung to the camp’s empty parade ground as Corporal Deer Weiss stood at the window of his barracks. Two years had passed since that first train ride into captivity. The young, defiant soldier, who’d arrived starving and bitter in 1943 was gone. The man staring through the glass now looked older.

Lines at the corners of his eyes, the weight of reflection carved into his face. He held his tin cup, steam curling upward from his tea. The same tea he’d been served nearly every morning since capture, once a reminder of defeat, now a symbol of survival. Outside, British guards were taking down the old wooden signs.

The white letters prisoner of war camp 198 had begun to fade. Trucks idled near the gate, their engines low and patient. Today, the Germans would be going home. Inside the messaul, the mood was strange, half joy, half sorrow. Men packed what little they owned. Letters, sketches, folded bits of newspaper. Some laughed, some cried, others simply sat in silence.

Then came the announcement over the loudspeaker, calm and deliberate. All prisoners will assemble in the yard at 0800. Breakfast will be served beforehand. All men to be ready for transport by 1000 hours. Breakfast. It felt like a fitting end. One last meal on British soil. Shared not as enemies, but as men who had survived the unthinkable.

Deer walked to the mess hall with his friend Hans Keller, the mechanic from Munich. The dawn light filtered through the clouds, painting the mud with silver. The smell met them before they even reached the door. Not just porridge this time, but something else. Something richer. Inside the long tables were already set.

On each plate, a full breakfast, eggs, bread, butter, porridge, and jam. The cooks had done more than duty. They had prepared a farewell. Sergeant Collins, now in a faded uniform, but still with that same calm authority, stood near the front, clipboard in hand. He looked around the hall and then raised his voice. “Well, lads,” he said, “Looks like we’ve come to the end of it, eh? You gave us no trouble, worked hard, and behaved like soldiers. Be proud of that. Eat up.

You’ve earned it. The men responded with scattered applause, awkward, unsure, but heartfelt. The British cook smiled, embarrassed, and went back to ladelling porridge. Deer sat down at his usual place, staring at the plate before him. Eggs, butter, jam, simple things, but to a man who’d once starved in the desert, they looked like a feast.

As he lifted the spoon to his mouth, he felt Hans nudge him. You’ll remember this breakfast for the rest of your life, won’t you? Ter smiled faintly. I already do. When the meal was nearly done, the door at the far end opened, and Lieutenant Mary Harrington, the camp nurse, stepped in. She wore her crisp uniform, her hair tucked neatly beneath her cap, but her eyes carried the same tired kindness as before.

The prisoners rose instinctively, not because they had to, but out of respect. Mary smiled gently. “No need for formality,” she said. “You’re free men now,” she paused, then added softly. I wanted to say goodbye. “You’ve all shown more dignity than many soldiers I’ve treated on either side. Don’t forget that.

” She walked down the aisle between tables, shaking hands with a few of the men. When she reached deer, she stopped. He stood slowly, meeting her gaze. “You kept us alive,” he said simply. “Mary smiled. You kept yourselves alive. We just gave you breakfast. He hesitated, then reached into his pocket. From it, he pulled a folded scrap of paper.

A small drawing of the camp he’d sketched months ago. The barracks, the wire, the British flag waving above it. He handed it to her. For you, he said. So, you remember we were here. She unfolded it, eyes softening. I won’t forget. Then she looked back up at him. Go home, Corporal Weiss. Start over. The world needs men who’ve seen mercy.

By midm morning, the prisoners gathered in the yard. The sun had broken through the clouds, now warm and golden, cutting through the last chill of English air. Trucks lined the road beyond the gate, ready to take them to the port. Each man received a final ration bag, bread, cheese, and a small tin of jam.

Even now, the British couldn’t help but feed them. Sergeant Collins moved through the line, shaking hands one by one. When he reached Deer, he gave a firm nod. “Weisse, isn’t it, good man? You’ll do well.” Deer gripped his hand tightly. “Thank you, Sergeant, for everything.” Collins smirked faintly.

“Just doing our job.” Then, after a pause, he added. “But I’m glad we did it right.” As the trucks rolled out, the camp began to disappear behind them. The fences, the guard towers, the huts. Deer looked back through the wooden slats of the truck bed, watching the place where he’d rediscovered his humanity grow smaller and smaller until it vanished into the mist.

Hans sat beside him, holding his ration bag on his knees. “So,” he said quietly, “What’s the first thing you’ll do when you’re home?” Deer thought for a moment. “Eat breakfast with my family,” he said. Hans laughed softly. “Let me guess. Porridge.” Deer smiled. Maybe, but this time I’ll make it for them.

Hours later, the convoy reached the harbor. Ships waited, their decks lined with men, ready to return home to a country in ruins. But the prisoners didn’t cheer. They just watched the horizon, uncertain, solemn. As Deer stepped onto the gang plank, the British flag above the dock caught the wind. He stopped for a moment, hand resting on the railing.

That flag had once meant defeat to him. Now, strangely, it meant something else. Honor. He thought back to the words his mother had written in her letter nearly two years before. Eat, my son. Sleep. The war will end one day, and when it does, I want you home with both hands and both feet. He looked down at his hands, steady, whole, alive.

That night, as the ship pulled away from England’s shore, the men gathered on deck. Someone began humming softly. that old tune, Lily Marlene. Others joined in, their voices low and rough, but filled with something the war had tried to kill. Hope. Deer stood at the rail, watching the lights of the English coast fade into darkness.

He thought of the breakfast that had started it all, that simple bowl of porridge on a cold morning in May 1943. It wasn’t just food. It was proof that mercy could survive even the worst of humanity, he whispered to himself. Enemies fed us. Enemies healed us. And somehow they reminded us what it meant to be human.

As the waves rocked the ship and dawn crept over the sea, deer closed his eyes. The war was over. But the memory of that breakfast, that small, humble act of kindness, would stay with him for the rest of his life.

News

CH2 . May 8th, 1945. The day the war officially ended. 10-year-old Helmet Schneider pressed his face against the cold cellar wall, listening to the rumble of American tanks rolling through his street. His mother’s hand gripped his shoulder so tightly it hurt, but he did not complain.

May 8th, 1945. The day the war officially ended. 10-year-old Helmet Schneider pressed his face against the cold cellar wall,…

CH2 . Lieutenant Junior Grade Kau Hagawa gripped the control stick of his P1Y Francis bomber as anti-aircraft fire exploded around his aircraft. Through the canopy, he could see the American task force spread across the ocean below battleships, cruisers, destroyers. Somewhere down there was his target, the cruiser USS San Francisco. This was Hagawa’s moment.

Japanese Kamikaze Pilot Thought He’d Be Executed — But the Americans Saved Him Instead.. Lieutenant Junior Grade Kau Hagawa gripped…

CH2 . Lieutenant Cara Mitchell stood at the edge of the training grounds at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, watching the morning fog roll in from the Pacific. The salt air clung to her skin as she mentally prepared for the day ahead. At 5’4 and 130 lbs, she knew what the SEALs would see when she walked into that training hall.

Lieutenant Cara Mitchell stood at the edge of the training grounds at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, watching the morning fog…

CH2 . Camp Florence, Arizona. July 1944. The 4th of July celebration smelled of charcoal and frying onions. And Sergeant Maria Kaufman watched the American guards set up a strange assembly lying metal grills, split bread rolls, pink sausages that looked nothing like German worst.

Camp Florence, Arizona. July 1944. The 4th of July celebration smelled of charcoal and frying onions. And Sergeant Maria Kaufman…

CH2 . Why the 5th Air Force Ordered Japanese Convoy Survivors to be Strafed in their Lifeboats…? March 1943, the JN dispatched 16 ships from Rabbal.

Why the 5th Air Force Ordered Japanese Convoy Survivors to be Strafed in their Lifeboats…? March 1943, the JN…

CH2 . How American B-25 Strafers Tore Apart an Entire Japanese Convoy in a Furious 15-Minute Storm – Forced Japanese Officers to Confront a Sudden, Impossible Nightmare…

How American B-25 Strafers Tore Apart an Entire Japanese Convoy in a Furious 15-Minute Storm – Forced Japanese Officers to…

End of content

No more pages to load