May 8th, 1945. The day the war officially ended. 10-year-old Helmet Schneider pressed his face against the cold cellar wall, listening to the rumble of American tanks rolling through his street. His mother’s hand gripped his shoulder so tightly it hurt, but he did not complain.

They had been hiding in this basement for 3 days, surviving on a single loaf of moldy bread and rainwater collected in a rusty bucket. Helmet had heard the stories. Every child in Frankfurt had heard them. The Americans were coming to punish Germany, to make them starve. His teacher, Hair Mueller, had told the class 6 months earlier that the enemy soldiers would take everything, every potato, every scrap of food, every blanket.

They will leave us to freeze and starve, Mueller had said, his voice shaking with conviction. It is their revenge for what Germany has done. The boy’s stomach cramped with hunger. He had not eaten a proper meal in weeks. The bombing had destroyed their apartment building. His father was dead killed on the Eastern Front 2 years ago. His older brother had disappeared during the Battle of Berlin.

Now it was just Helmet, his mother, and his six-year-old sister Greta, who had stopped crying from hunger because she no longer had the energy. Through the basement window, Helmet could see boots, American boots, dark green uniforms. The conquerors had arrived.

His mother began to pray quietly in the darkness, her voice trembling. Helmoot thought about the propaganda posters he had seen Americans depicted as monsters, thieves, destroyers. He thought about the stories of cities raised, populations displaced, food supplies seized. “They will take everything,” his mother whispered. “God help us.

They will take everything we have left. But Helmet’s family had nothing left to take. Just their lives barely clinging to them in a destroyed city where the smell of death hung in the spring air. The boy closed his eyes and waited for the worst. But what happened next would change everything he thought about Americans.

The basement door crashed open on their fourth day of hiding. Sunlight streamed down the stairs. The first sunlight helmet had seen in days. His mother pulled both children behind her, shielding them with her emaciated body. Helmet could see her ribs through her thin dress. Heavy footsteps descended. American soldiers, three of them, with rifles slung over their shoulders.

The lead soldier was tall, maybe 30 years old, with dark hair and a tired face. His uniform bore the insignia of the Third Armored Division. “Pitta,” Helmet’s mother begged in German, her voice breaking. Please, the children do not hurt the children. Helmet expected shouting. Violence. The butt of a rifle. Instead, the American soldier slowly lowered his weapon and held up both hands, palms open.

“It is okay,” he said in broken German. “Alice Gut, we are checking buildings, making sure everyone is alive.” The soldier’s eyes scan the basement, the bucket of gray water, the moldy breadcrust, the three skeletal figures huddled in the corner. Helmet watched the American’s face change………….![]()

![]()

![]()

German Children Expected Starvation — American GIs Gave Them Half Their Rations Daily

Frankfurt, Germany. May 8th, 1945. The day the war officially ended. 10-year-old Helmet Schneider pressed his face against the cold cellar wall, listening to the rumble of American tanks rolling through his street. His mother’s hand gripped his shoulder so tightly it hurt, but he did not complain.

They had been hiding in this basement for 3 days, surviving on a single loaf of moldy bread and rainwater collected in a rusty bucket. Helmet had heard the stories. Every child in Frankfurt had heard them. The Americans were coming to punish Germany, to make them starve. His teacher, Hair Mueller, had told the class 6 months earlier that the enemy soldiers would take everything, every potato, every scrap of food, every blanket.

They will leave us to freeze and starve, Mueller had said, his voice shaking with conviction. It is their revenge for what Germany has done. The boy’s stomach cramped with hunger. He had not eaten a proper meal in weeks. The bombing had destroyed their apartment building. His father was dead killed on the Eastern Front 2 years ago. His older brother had disappeared during the Battle of Berlin.

Now it was just Helmet, his mother, and his six-year-old sister Greta, who had stopped crying from hunger because she no longer had the energy. Through the basement window, Helmet could see boots, American boots, dark green uniforms. The conquerors had arrived.

His mother began to pray quietly in the darkness, her voice trembling. Helmoot thought about the propaganda posters he had seen Americans depicted as monsters, thieves, destroyers. He thought about the stories of cities raised, populations displaced, food supplies seized. “They will take everything,” his mother whispered. “God help us.

They will take everything we have left. But Helmet’s family had nothing left to take. Just their lives barely clinging to them in a destroyed city where the smell of death hung in the spring air. The boy closed his eyes and waited for the worst. But what happened next would change everything he thought about Americans.

The basement door crashed open on their fourth day of hiding. Sunlight streamed down the stairs. The first sunlight helmet had seen in days. His mother pulled both children behind her, shielding them with her emaciated body. Helmet could see her ribs through her thin dress. Heavy footsteps descended. American soldiers, three of them, with rifles slung over their shoulders.

The lead soldier was tall, maybe 30 years old, with dark hair and a tired face. His uniform bore the insignia of the Third Armored Division. “Pitta,” Helmet’s mother begged in German, her voice breaking. Please, the children do not hurt the children. Helmet expected shouting. Violence. The butt of a rifle. Instead, the American soldier slowly lowered his weapon and held up both hands, palms open.

“It is okay,” he said in broken German. “Alice Gut, we are checking buildings, making sure everyone is alive.” The soldier’s eyes scan the basement, the bucket of gray water, the moldy breadcrust, the three skeletal figures huddled in the corner. Helmet watched the American’s face change.

The soldier said something in English to his companions, and one of them immediately turned and ran back up the stairs. “When did you last eat?” the soldier asked in English, then tried again in halting German. “Essen food. When?” Helmut’s mother did not answer. She was trembling, confused by the gentleness in the soldier’s voice. This was not what they had been told to expect.

The boy found his own voice thin and weak. Three days bread three days ago. The American soldier, Helmet, would later learn his name was Private James Morrison from Ohio, knelt down to the boy’s eye level. He was so close Helmet could see the mud on his uniform, smelled the strange scent of American cigarettes. Morrison reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out a chocolate bar. A Hershey’s bar.

Helmet had seen chocolate. exactly twice in his life, both times before the war. He stared at it like it was a hallucination. “Here,” Morrison said, pressing it into the boy’s hand. “Eat!” Helmet looked at his mother for permission. She was crying now, silent tears streaming down her hollowed cheeks.

The boy’s fingers shook as he tore open the wrapper. The sweetness exploded in his mouth, so intense he almost could not swallow. He immediately broke off a piece for Greta, who ate it so fast she choked, and his mother had to pat her back while crying harder. The second American soldier returned with two more GIS. They were carrying boxes, Krations, canned goods, military bread.

They set them on the basement floor like offerings. There is a field kitchen two blocks west, Morrison said, gesturing. Hot food for everyone, you understand? For civilians, free. You go there. Helmet’s mother shook her head in disbelief. Why? She whispered in German. Why would you feed us? Morrison did not understand the words, but he understood the question in her eyes.

He pulled out a photograph from his wallet. A woman and two young children, probably his own family back in Ohio. He pointed to the photo, then to Helmet and Greta. Kids are kids, he said simply in English. Then he stood up and headed toward the stairs. Before leaving, he turned back and added in broken German.

Durkist is vor the war is over. The field kitchen was set up in the shell of what had been Frankfurt’s central market. Helmet held Greta’s hand as they approached with their mother, still expecting this to be some kind of trick. But the smell asterric asterisk God.

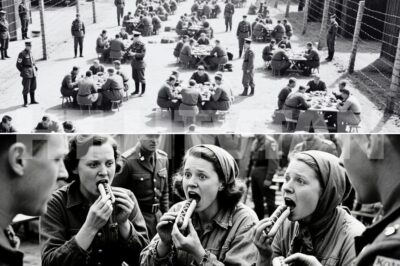

The smell of cooking food asterric asterk made his stomach twist with desperate hunger. There was a line. Dozens of German civilians, all looking as skeletal and shell shocked as Helmet’s family. And at the front of the line, American soldiers were serving food, not throwing scraps, not forcing people to beg, serving food on metal trays, one person at a time, with an efficiency that seemed almost surreal.

When Helmet reached the front, a asterisk asterisk Black American Sergeant Staff Sergeant William Davis from Georgia asterisk asterisk lad hot soup into a bowl and handed it to him with both hands like it was precious. Slow, Davis said, gesturing to his own mouth. Eat slow, you understand? Too fast, you get sick.

The soup was thin, mostly broth with some vegetables and bits of meat, but to helmet it tasted like heaven. His mother wept openly as she fed Greta. one careful spoonful at a time. All around them, German civilians were crying as they ate. Not from sadness, from the overwhelming shock of being treated like human beings. Helmet watched the American soldiers.

They were eating too, but their portions were noticeably smaller than what they were serving civilians. One soldier, a young private who could not have been more than 19, gave his entire meat portion to an elderly German woman who reminded him of his grandmother. Helmet saw him do it. The private just smiled and ate his bread and vegetables. This was not supposed to happen.

The propaganda had promised American cruelty, starvation, revenge. But here were enemy soldiers going hungry to feed German children. Over the following days, Helmet’s family was assigned to a temporary shelter in a partially intact school building. The Americans had divided Frankfurt into sectors, establishing food distribution points, medical stations, and housing registries.

The organization was impressive, almost Germanic in its efficiency, which Helmet’s mother remarked upon with a bitter laugh. Helmet began going to the American Distribution Center every morning with a wagon to collect the daily rations for the families in his building. It was there that he really got to know Private Morrison and the other soldiers of the Third Armored Division.

Morrison was 28, a factory worker from Cleveland before the war. He showed helmet photographs of his family, his wife Margaret, his daughters Betty and Susan, ages seven and nine, almost Helmet’s age. The private carried those photos everywhere, looked at them every night before sleeping. “They look like good girls,” Helmet said in the broken English he was rapidly learning.

Best girls in the world, Morrison replied, his eyes soft. That is why I am here. So they never have to see what you have seen. So no kid has to go through this. The conversation stuck with Helmet. Morrison had just spent months fighting Germans, had lost friends to German bullets and shells.

Yet here he was splitting his rations with German children because he thought of his own daughters. The cognitive dissonance was staggering. But it was not just Morrison. There was Corporal Anthony Russo from Brooklyn who organized baseball games with German children using a stick and a ball made of wrapped cloth.

There was Private First Class Robert Chen, a Chinese American from San Francisco, who taught Helmet basic English phrases while they worked together to clear rubble from the streets. There was Sergeant Davis, who set up an improvised school in the evenings, teaching German children American folk songs and simple arithmetic.

The Americans did not act like conquerors. They acted like, well, like people who had a job to do and were determined to do it right. One afternoon in late May, Helmet was helping Morrison unload supply trucks. A job the soldiers gave him in exchange for extra rations for his family. A crate slipped and fell, splitting open and spilling cans of meat across the ground.

Helmet immediately dropped to his knees to gather them up. apologizing frantically. He expected anger, maybe punishment. Instead, Morrison just laughed. “It is okay, kid. Accidents happen. You are not in trouble.” “You are not angry?” Helmet asked, confused. Morrison tilted his head, genuinely puzzled by the question.

“Why would I be angry? You did not do it on purpose. We will just pick them up.” This casual forgiveness, this assumption of good intentions, it was revolutionary to a boy raised in a system built on punishment and fear. Helmet had been trained to expect harsh consequences for every mistake. But these Americans seemed to operate on entirely different principles.

As weeks passed and spring turned to early summer, Helmet began to understand that what he was witnessing was not exceptional behavior from a few kind soldiers. It was American military policy. The Geneva Convention guided their actions.

But so did something deeper, a fundamental belief that even defeated enemies deserved basic human dignity. His mother made friends with other German women at the shelter. And they shared stories. In the American zone, food was distributed fairly. Medical care was available. Soldiers were punished severely for mistreating civilians. One private was court marshaled and discharged for stealing from a German family.

The Americans documented everything, filed reports, followed rules even when no one was watching. This was in stark contrast to what they heard from refugees coming from the Soviet zones in the east where a different kind of occupation was unfolding. The stories from the east were nightmarish, wholesale retribution, mass displacement, systematic plundering.

Helmet’s mother, who had initially felt a strange guilt about accepting American help, began to realize that her family had been extraordinarily fortunate to end up in the Western sector. Helmet overheard American officers talking one day about something called the Marshall Plan, some future American program to rebuild Europe. At first, he could not believe it.

Why would the victors spend money to rebuild the countries that had just tried to destroy them? But the more he watched these soldiers share their food, their time, their humanity, the more it made a strange kind of sense. The moment that changed everything for Helmet came in early June, about a month after the war’s end.

He was helping at the distribution center when a commotion broke out. An elderly German man, Her Vogel, a former Vermach soldier who had lost his left arm at Stalenrad, had collapsed from malnutrition. Helmet watched as Sergeant Davis immediately radioed for a medic and knelt beside Vogle, checking his pulse, speaking calmly to keep him conscious.

The medic arrived a young Jewish soldier from New York named David Goldstein. Helmet saw the Star of David necklace hanging outside Goldstein’s uniform. He saw hair Vogel’s face go pale as he realized a Jewish American soldier was treating him. The old man tried to refuse treatment, mumbling something about not deserving it, about what Germany had done. Goldstein cut him off.

Sir, I am a medic. You are a patient. That is all that matters right now. He started an IV line with steady hands. We are going to get you to the hospital. Get some food in you properly. You are going to be fine. Helmet watched Hair Vogle begin to cry deep, racking sobs that shook his whole body. I do not deserve this. the old man kept saying, “Not from you.

Not after everything.” Goldstein paused, his face unreadable. Then he said quietly, “Maybe not, but that is not for me to decide. My job is to heal people. Your job is to get better and help rebuild this city so it never happens again. Deal?” Vogle nodded, unable to speak. As they loaded him into the ambulance, Goldstein turned to Helmet, who had been translating.

Tell him, Goldstein said that the best revenge is helping Germany become better. Tell him we are not here to destroy. We are here to help you get it right this time. Helmet translated and Vogle nodded again, tears still streaming down his weathered face. That moment crystallized something for Helmet. These Americans weren’t naive. They knew what Germany had done.

Goldstein certainly knew his grandparents had died at Awitz. Helmet would later learn. But they had made a conscious choice to respond to hatred with humanity, to answer violence with mercy. Not because Germans deserved it, but because it was the right thing to do. Another incident weeks later, Morrison’s daughter Susan had a birthday.

He showed Helmet a letter from his wife with a photograph of the birthday party back in Ohio. “She is nine now,” Morrison said, smiling, but with wet eyes. “I missed it.” On impulse, Helmet ran back to the shelter and returned with something he had been saving. A small wooden figure of a bird he had carved from rubblewood. It was crude, but it was the only thing of value he owned.

“For your daughter,” Helmet said, pressing it into Morrison’s hand. “For her birthday. From Germany.” So she knows. So she knows not all Germans are bad. Morrison looked at the carving for a long moment. Then he pulled Helmet into a hug. The first time a man had hugged the boy since his father died. “Thank you,” Morrison whispered.

“I will tell her all about the brave German kid who helped us feed his city. I will tell her about you, Helmet.” The boy sobbed into the American shoulder, releasing months of fear and grief and confusion. “When Morrison finally let go, he was crying, too. “The war is over, kid,” Morrison said, wiping his eyes. “Time to be friends now.

” By July 1945, Helmet had gained 15 pounds. His mother had found work helping the Americans with translation. Greta was smiling again, playing with other children. The city was still rubble, but there was food. There was hope. Helm asked Morrison one day why Americans were being so kind. Morrison thought for a long moment before answering.

“My sergeant told me something when we crossed into Germany,” he said. He said, “The Germans started this war, but we are going to finish it right. We are going to show them what a decent country looks like so they never want to go down this road again.” He said, “The best way to win a war is to make your enemy not want to be your enemy anymore.

” Morrison gestured around at the children playing, the families receiving rations, the city slowly coming back to life. Every meal we give you, every bit of kindness we show, it is an investment. We are investing in peace because if we treat you right now, maybe your generation will not want to fight us in 20 years.

Maybe you will remember that Americans are decent people and you will help build a Germany that is decent, too.” He paused, then added softly. “Plus, you are just a kid. You did not start this war. You are just a victim of it. Same as my daughters would have been if Germany had won.

What kind of man would I be if I let kids starve just because of what their government did?” The treatment Helmwood experienced was not an accident or the result of a few exceptionally kind soldiers. It was deliberate American policy rooted in both practical strategy and deeply held values. The Geneva Convention of 1929 established standards for prisoner of war treatment. But the American military went beyond minimum requirements.

General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied forces in Europe, issued clear directives. Defeated Germans were to be treated firmly but fairly. Food was to be distributed equitably. Medical care was to be provided. Abuses were to be prosecuted. This was not just idealism. American military leadership understood that how they treated defeated Germany would determine whether they faced another war in a generation.

The harsh treatment of Germany after World War I, the punitive reparations, the economic destruction, the national humiliation had created fertile ground for Hitler’s rise. American planners were determined not to repeat that mistake. But there was also something deeper. American cultural values that emphasized individual dignity, fair play, and the capacity for redemption.

Soldiers like Morrison, Davis, and Russo had been raised in a democracy that, despite its flaws, believed people deserve basic rights. They had been taught that even enemies could become friends if treated with respect. For Helmet and millions of German civilians, the gap between what they had been told to expect and what they actually experienced was impossible to ignore.

The Nazi propaganda machine had spent years painting Americans as barbarians who would destroy Germany. Instead, Americans arrived with food, medicine, and plans to rebuild. This cognitive dissonance was transformative. Helmut’s mother, who had been a dutiful Nazi party member, as most Germans had been, whether by conviction or compulsion, began questioning everything she had been told.

If the Americans were not monsters, what else had been lies? If the enemy showed more humanity than her own government, what did that say about the cause Germany had fought for? In the months and years that followed, as the full extent of Nazi atrocities became public, this question would haunt an entire generation of Germans. But in those early days of occupation, the seeds were planted.

The Americans they had been taught to hate were treating them better than their own government ever had. German civilians kept diaries and wrote letters during this period. Many of these documents survived the war and provide powerful testimony. One woman from Frankfurt wrote in June 1945, “The Americans share their food with us, though they have every reason to hate us. I cannot reconcile this with what we were told.

Either the Americans are fools or we were the fools for believing the lies.” Another German, a former school teacher wrote, “They treat us like human beings. After what Germany did, I expected retribution. Instead, they are helping us rebuild. I am ashamed of what my country became and grateful for the mercy we do not deserve.

” By the summer of 1945, the US military was feeding approximately 4 million German civilians in the American occupation zone. They were distributing roughly 1,500 calories per person per day, barely enough to survive. But in a devastated nation with shattered infrastructure, it meant the difference between life and death. American soldiers were eating rations containing about 3,000 to 4,000 calories daily.

But countless GIs like Morrison were giving away portions of their own food. It wasn’t officially sanctioned, but officers generally looked the other way. The result was American soldiers operating at reduced efficiency, dealing with their own hunger to ensure German children had enough to eat.

The cost to the American taxpayer was substantial. In 1945 to 1946 alone, the US spent over $200 million, equivalent to about $3.5 billion today, on emergency food relief for occupied Germany. This was before the Marshall Plan even began, before the massive reconstruction efforts that would define the late 1940s.

Compare this to the Soviet occupation zone, where systemic plundering was official policy. The Soviets dismantled entire factories and shipped them to Russia as war reparations. They seized food supplies, often leaving German civilians to starve. The contrast couldn’t have been more stark, and Germans noticed.

The flood of refugees from east to west became a tidal wave. By 1946, over 5 000000 German PSWs had been repatriated from American custody, most in good health. The Americans also began programs to re-educate Germans about democracy, establishing newspapers, radio stations, and eventually schools built on democratic principles. They didn’t just want to defeat Germany militarily.

They wanted to transform it ideologically. Helmoot Schneider grew up in the American sector of Frankfurt. He attended schools rebuilt with American aid, learned English from American teachers, and never forgot the soldiers who had saved his life in May 1945. In 1948, when the Berlin Airlift began that famous operation where American and British pilots flew thousands of missions to break the Soviet blockade of Berlin, Helmet volunteered to help at the Frankfurt air base.

He was 13 years old, watching C-47 cargo planes take off every few minutes, carrying food and coal to besieged Berliners. The airlift was the logical continuation of the compassion he had experienced 3 years earlier. Americans refusing to let Germans starve, even at tremendous cost. By the 1950s, Helmut had graduated from an American sponsored gymnasium and was working as a translator for the United States military government.

He helped bridge the gap between American administrators and German civilians. Using his unique perspective to help both sides understand each other, he never lost contact with Private Morrison. They exchanged letters for decades. Morrison returned to Ohio, went back to his factory job, and raised his daughters.

Helmet sent him updates about Frankfurt’s reconstruction, the buildings rising from rubble, the economy recovering, democracy taking root. Morrison sent photos of his family growing up in peaceime America. In 1985, on the 40th anniversary of VE Day, Helmoot traveled to Ohio to meet Morrison in person for the first time since 1945. The two men, now in their 50s and 60s, embraced at the airport like long-lost brothers. Helmoot met Susan Morrison, now a middle-aged woman with children of her own.

He gave her the wooden bird carving he had made for her birthday in 1945. Morrison had kept it all those years. You saved my life, Helmet told Morrison during that visit. You and the other soldiers, you showed me what kind of country America was. You are the reason I believe democracy could work in Germany. Morrison, his eyes damp, replied, “You helped me too, Helmet.

You reminded me why we fought, not to destroy, but to save. You made it all mean something.” The compassionate treatment of German civilians by American forces was instrumental in winning the peace after World War II. Within 5 years of the war’s end, West Germany had become a stable democracy and a crucial American ally.

Within 10 years, it was an economic powerhouse, the German economic miracle that shocked the world. This transformation was not inevitable. It required the Marshall Plan, $12 billion in American aid to rebuild Western Europe, including former enemies. It required American troops to remain as protectors rather than occupiers.

It required Americans to invest in Germany’s future despite the recent past. But most importantly, it required the foundation laid in those early days by soldiers like Morrison, who shared their rations with enemy children and showed through daily actions that Americans were not conquerors seeking revenge, but liberators offering a better path forward.

The contrast with Eastern Europe is instructive. Countries under Soviet occupation remained occupied for 45 years. Their economies stagnant, their people oppressed, their relationship with their occupiers poisoned by resentment. Meanwhile, Germany split in two. The democratic prosperous West allied with America and the authoritarian, struggling East dominated by the Soviets.

The difference in treatment during occupation created a difference in outcome that lasted nearly half a century. By the time the Cold War began in earnest, Germany was the front line. And West Germans, who might have been expected to resent American military presence after the devastation of the war, instead welcomed American troops as protectors because they remembered how those troops had treated them in 1945.

They remembered the food, the medicine, the kindness. They trusted Americans because Americans had earned that trust when it mattered most. In 2005, 60 years after the end of World War II, German television produced a documentary about the occupation period, they interviewed Helm Schneider, now 70 years old and a retired businessman.

His testimony was powerful. I expected to die in May 1945. I expected Americans to treat us the way we Germans had treated others with cruelty, with revenge, with hate. Instead, they gave us hope. They gave us food when they were hungry themselves. They treated us like human beings when we’d barely been human to others.

That paradox that we were shown mercy we hadn’t earned and didn’t deserve, it broke something in me. It broke the propaganda. It made me question everything I’d been taught. And it made me determined to help build a Germany worthy of the second chance we’d been given. He paused, emotion thick in his voice. Americans didn’t just defeat Germany. They redeemed Germany.

They showed us a better way. Everything I accomplished in my life, my education, my career, my family success, it all started with a chocolate bar from a soldier from Ohio who saw a starving child and couldn’t walk away. That’s the America I know. That’s the America that saved my life.

Helmet passed away in 2012 at age 77. At his funeral, his children read letters he had exchanged with James Morrison over 47 years. They displayed the Hershey’s bar wrapper he had kept framed on his office wall, the first American food he had ever tasted, preserved as a reminder of the Day Hope returned to Germany.

Morrison himself had died in 1998, but his daughter Susan attended Helmet’s funeral. She spoke about the wooden bird carving still displayed in her home and what it represented. Two men from enemy nations who became brothers. A boy who represented everything my father fought against. Becoming proof of why he fought to save the innocent, to preserve the future, to choose mercy over revenge.

Their friendship was the peace dividend. It was what victory was supposed to look like. Helmet Schneider’s story isn’t unique, but it is uniquely important. multiply his experience by millions and you begin to understand how America won not just a war but a peace that lasted generations. The lesson is profound.

How you treat defeated enemies determines whether they remain enemies. America understood this in 1945 and made a conscious choice to break the cycle of revenge that had dominated European politics for centuries. Instead of punishing Germany into submission, America lifted Germany into partnership. This wasn’t soft or weak. It was strategically brilliant.

By investing in German recovery, America created a bull work against Soviet expansion. By treating Germans with dignity, America created millions of Germans grateful for American protection. By showing mercy when revenge would have been justified, America demonstrated the superior moral authority that made it the natural leader of the free world. But beyond strategy, there was genuine principle.

American soldiers shared their rations not because of orders from Washington, but because their consciences demanded it. They couldn’t watch children starve, even enemy children, even the children of the nation that had killed their brothers and friends. This wasn’t official policy. It was American character.

The contrast with how other victorious powers treated defeated enemies throughout history is striking. For millennia, conquest meant destruction, plunder, subjugation. America offered something revolutionary. Conquest followed by reconstruction, defeat followed by redemption, war followed by friendship. This model, the American model, became the template for how democracies engage with the world.

It wasn’t always followed, and American foreign policy has had many failures. But the Germany example remained powerful. Treat even enemies with dignity, and you can transform enemies into allies. In our current era of renewed great power competition, and persistent conflicts, Helmet’s story offers vital lessons.

The impulse to dehumanize enemies is as old as warfare itself. But history proves that dehumanization, while emotionally satisfying, is strategically foolish. Today’s enemy can become tomorrow’s ally, but only if you treat them in ways that make alliance possible. The challenge facing modern democracies is similar to what America faced in 1945.

How do you respond to genuine evil without becoming defined by revenge? How do you hold people accountable while leaving room for redemption? How do you win wars in ways that make lasting peace possible? The American soldiers in Frankfurt in 1945 provide a model. They didn’t excuse what Germany had done. They didn’t forget the friends they’d lost or the atrocities they’d uncovered.

But they separated past crimes from future possibilities. They saw German children not as Nazi spawn deserving punishment but as human beings needing help. They believed in the possibility of change and they invested in that possibility with their own food and their own compassion.

This is the essence of American exceptionalism at its best. Not the claim that America is perfect or superior, but the aspiration to lead through example, to win through values, to prove that democracy and human dignity can triumph even in the worst circumstances. When American soldiers today deploy abroad, they carry this legacy. When America invests in rebuilding nations, it has fought. It echoes the Marshall Plan.

When Americans debate how to treat refugees, prisoners, and civilians in conflict zones, they are wrestling with the same questions Morrison faced in Frankfurt. What does it mean to be the good guys? What do our values demand of us, even when it’s costly? The answer Helmouth’s generation received asterisk asterisk food, hope, mercy, and a second chance asterisk asterisk helped create 70 years of peace between nations that had fought three major wars in 75 years.

That’s not just a feel-good story. That’s proof that treating enemies with humanity isn’t weakness. I tease the most powerful weapon in a democracy’s arsenal. In an age of asterisk asterisk polarization, both internationally and within nations, asterisk asterisk stories like Helmoots remind us that people are not their governments.

Ordinary Germans in 1945 were victims of their own nation’s ideology just as they had been perpetrators of terrible crimes. The American response to punish criminals while helping civilians, to hold leaders accountable while feeding children, represented a sophisticated understanding that evil regimes and ordinary people are not the same thing. This nuance is desperately needed today.

In conflicts around the world, it’s easy to demonize entire populations based on the actions of their leaders or extremists. But most people everywhere just want safety, food, family. hope exactly what Helmet wanted in May 1945. When democracies treat ordinary people with dignity, even during conflict, they plant seeds of future friendship.

The viral power of this story and thousands like it also matters. German children who received American rations grew up to be German adults who told their children about American kindness. Those children told their children. Three generations of Germans have grown up with family stories about the Americans who saved their grandparents.

This cultural memory is why the US German alliance has been so strong, so durable, so emotionally meaningful beyond just strategic interest. Contrast this with regions where America’s record has been more mixed, where civilians experienced American power without American compassion, where military victory wasn’t followed by Marshall Plan, level investment in reconstruction and redemption.

The difference in outcomes is telling. Helmet’s story is a reminder that wars end, but memories last. The ammunition we expend eventually runs out, but the impressions we leave on civilian populations can shape geopolitics for generations. Every act of kindness, every moment of restraint, every display of values under pressure, these become stories that outlast the conflicts themselves.

In May 1945, 10-year-old Helmet Schneider huddled in a Frankfurt basement, waiting to die or starve or worse. He had been taught that American soldiers were monsters who would show no mercy to defeated Germany. He was wrong. Completely, fundamentally wrong. The Americans who rolled into his destroyed city brought chocolate and hope and hot soup and humanity.

They went hungry so German children could eat. They spent their own money, gave their own food, shared their own family photos because their consciences demanded it and their values required it. Helma did not just survive. He thrived. He built a life in the democracy Americans helped establish.

He became living proof that yesterday’s enemy could become today’s friend, that mercy was not weakness, that treating people with dignity could transform nations. This was not just American military doctrine. This was not just Geneva Convention compliance. This was American character.

Millions of individual soldiers making millions of individual choices to be decent human beings even when no one would have blamed them for revenge. Private James Morrison gave Helmet Schneider a chocolate bar in May 1945. That single act of kindness, multiplied by countless others, helped create the Western Alliance, the European Union, 70 years of peace, and proof that democracies do not just win wars. They win the peace that follows.

Remember Helmet. Remember Morrison. A starving child expected death and found humanity instead. Do you have a family story about the post-war occupation, the Berlin airlift, or American treatment of former enemies? Share it in the comments below. These stories matter. They remind us that even in our darkest moments, choosing compassion over revenge can literally change the

News

CH2 . Lieutenant Junior Grade Kau Hagawa gripped the control stick of his P1Y Francis bomber as anti-aircraft fire exploded around his aircraft. Through the canopy, he could see the American task force spread across the ocean below battleships, cruisers, destroyers. Somewhere down there was his target, the cruiser USS San Francisco. This was Hagawa’s moment.

Japanese Kamikaze Pilot Thought He’d Be Executed — But the Americans Saved Him Instead.. Lieutenant Junior Grade Kau Hagawa gripped…

CH2 . Lieutenant Cara Mitchell stood at the edge of the training grounds at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, watching the morning fog roll in from the Pacific. The salt air clung to her skin as she mentally prepared for the day ahead. At 5’4 and 130 lbs, she knew what the SEALs would see when she walked into that training hall.

Lieutenant Cara Mitchell stood at the edge of the training grounds at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, watching the morning fog…

CH2 . Camp Florence, Arizona. July 1944. The 4th of July celebration smelled of charcoal and frying onions. And Sergeant Maria Kaufman watched the American guards set up a strange assembly lying metal grills, split bread rolls, pink sausages that looked nothing like German worst.

Camp Florence, Arizona. July 1944. The 4th of July celebration smelled of charcoal and frying onions. And Sergeant Maria Kaufman…

CH2 . Starving German POWs Couldn’t Believe What Americans Served Them for Breakfast… May 17th, 1943, Northern England. Cold mist hung low over the railard, wrapping the countryside in a damp, gray silence. The cattle cars hissed as steam curled from beneath their iron wheels. Inside, 180 German soldiers waited, cramped and sleepless after 3 days of transport from the ports of Liverpool.

Starving German POWs Couldn’t Believe What Americans Served Them for Breakfast…May 17th, 1943, Northern England. Cold mist hung low over…

CH2 . Why the 5th Air Force Ordered Japanese Convoy Survivors to be Strafed in their Lifeboats…? March 1943, the JN dispatched 16 ships from Rabbal.

Why the 5th Air Force Ordered Japanese Convoy Survivors to be Strafed in their Lifeboats…? March 1943, the JN…

CH2 . How American B-25 Strafers Tore Apart an Entire Japanese Convoy in a Furious 15-Minute Storm – Forced Japanese Officers to Confront a Sudden, Impossible Nightmare…

How American B-25 Strafers Tore Apart an Entire Japanese Convoy in a Furious 15-Minute Storm – Forced Japanese Officers to…

End of content

No more pages to load