June 4 1942 Battle Of Midway From The Japanese Perspective – military history… Imagine you are Commander Tairo Aayoki, the seasoned air officer, standing on the flight deck of the flagship Akagi at 10:20 in the morning on June 4th, 1942.

For 6 months, your fleet has been invincible.

You were at Pearl Harbor.

You swept through the Indian Ocean.

Every enemy you’ve met has been brushed aside.

Below deck, the planes are being armed for the final decisive blow against the American fleet.

You’ve weathered their pathetic peacemeal countermeasures this morning.

You think the worst is over.

You are about to be fatally wrong.

This is the moment of ultimate triumph.

And then in the next 5 minutes, you will be engulfed in a terrible storm of fire and steel from which there is no escape.

You will watch as the most powerful naval force on the planet is utterly defeated.

How did it come to this?

How did it all go so wrong?

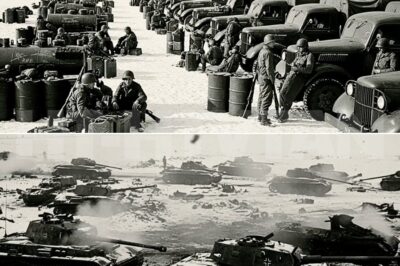

To get the sheer shock of Midway for the Japanese, you have to understand the mountain of confidence they were standing on.

After the stunning success at Pearl Harbor, the Kidai, the first airfleet led by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, went on a six-month period of great success.

They were the tip of the spear, the apex predator of the seas.

The force was built around six fleet carriers.

Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu, Shokaku, and Zuikaku.

These weren’t just ships.

They were floating airfields crewed by the most experienced naval aviators on the planet.

Many were veterans of the long war in China, hardened by years of real combat.

Their skill was breathtaking.

They could launch over 100 aircraft in less than 10 minutes, a level of efficiency their American counterparts were still struggling to match.

After Pearl Harbor, their conquest was relentless.

They supported invasions across the Pacific.

They defeated Allied naval power at the Battle of the Java Sea.

In April 1942, Nagumo led a five carrier force into the Indian Ocean, sending to the bottom the British carrier HMS Hermes and two heavy cruisers with almost casual ease.

They proved that no corner of the new Japanese Empire was beyond their reach.

This unbroken chain of victories led to a dangerous condition that Japanese officers would later call victory disease.

A deep-seated overconfidence started to influence the high command.

They believed their pilots were just naturally better.

Their fighting spirit was invincible, and their plans were flawless.

American morale, they figured, had to be compromised.

This arrogance wasn’t just an attitude.

It infected their strategic planning, blinding them to risks and causing them to wave off warnings that should have set off alarm bells.

The men of the Kidobai were the best in the world and they knew it.

They had never lost and they couldn’t imagine they ever would.

This supreme confidence followed them on the long voyage to a tiny atole in the middle of the Pacific, an atal named Midway.

The man behind the Midway operation was the brilliant and often reckless commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Isuroku Yamamoto.

Despite all the victories, Yamamoto was worried.

He had studied in the United States and he understood its industrial power in a way many of his colleagues didn’t.

He knew Japan had a very short window to win the war before America’s industrial engine roared to life and buried Japan under an avalanche of ships and planes.

Pearl Harbor hadn’t been a total success.

The American aircraft carriers had escaped.

As long as they were out there, the US Navy was a dagger pointed at the heart of Japan’s empire.

The do little raid in April 1942 when American bombers hit Tokyo itself was a profound humiliation that proved Yamamoto right.

Read the full article below in the comments ↓

Imagine standing on the flight deck of the mighty carrier Akagi, believing you are moments from final victory, only to learn that in the next 5 minutes, your world, your fleet, and everything you trusted will be consumed by fire. That is the shock of midway through Japanese eyes, a moment when absolute confidence became absolute catastrophe.

You are Commander Tyro Aayoki, a seasoned air officer aboard the flagship Akagi, standing on the flight deck at 10:20 a.m. June 4th, 1,942. For 6 months, your fleet has seemed untouchable. You were at Pearl Harbor. You helped sweep across the Indian Ocean, and every enemy task force you faced had been crushed with ease.

Below the deck, the planes are being armed for the final blow that will supposedly destroy the remaining American fleet. After weathering what looked like weak, uncoordinated U US counterattacks earlier, you believe the danger has passed. But you are wrong. Fatally wrong. In the next few minutes, you will witness the utter ruin of the strongest carrier force on Earth.

To understand how shocking this would be to the Japanese, you have to grasp the sheer mountain of confidence they were standing on. After Pearl Harbor, the Kido Bhutai, led by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo experienced six months of uninterrupted success. These were not ordinary fighting ships. They were floating fortresses of aviation, the heart of Japan’s offensive strength.

The combined carrier force of Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu, Shokaku, and Zuikaku represented the most formidable naval aviation power in existence. Their pilots were veterans hardened by years of combat in China. Trained to a level of skill unmatched anywhere in the world, their launch efficiency bordered on perfection over a hundred aircraft in under 10 minutes, a rhythm that American crews could only envy.

After Pearl Harbor, the Kido Bhutai’s attacks swept across the Pacific, defeated Allied naval forces at the Java Sea and delivered crushing blows in the Indian Ocean, sinking the British carrier HMS Hermes and heavy cruisers with alarming ease. No region seemed beyond Japan’s reach. To the men on these decks, defeat was simply not a possibility.

But this endless string of victories produced something far more dangerous than enemy fire. It produced victory disease, a creeping arrogance that infected the Japanese high command. Officers began believing their pilots were inherently superior, their fighting spirit unbeatable, and their strategies flawless.

They brushed aside warnings, underestimated American resilience, and assumed that the US was already broken in both morale and capability. Yet, not everyone in Japan’s Navy was blinded by triumph. Admiral Isuroku Yamamoto, the mastermind behind Pearl Harbor, understood the United States in a way many of his colleagues did not. Having studied in America, he knew how powerful its industries were.

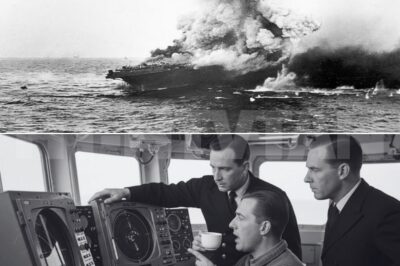

Japan, he realized, had only a short window to secure victory before the US began producing ships and aircraft on a scale Japan simply couldn’t match. Pearl Harbor had not destroyed the American carriers, and as long as those carriers survived, they threatened Japan’s entire Pacific plan. The Dittle raid, where American bombers struck Tokyo in April 1942, confirmed Yamamoto’s fear the American carriers had to be dealt with.

Thus was born Operation MI, the plan to seize Midway atal and lure the American fleet into a decisive battle. Yamamoto envisioned a perfectly constructed trap. The invasion of Midway would force the US Navy to respond. When it did, the full strength of the combined fleet, including battleships, carriers, submarines, and support forces, would destroy whatever remained of US naval power.

But the plan was too complex, too rigid, and ultimately built on faulty assumptions. It relied entirely on surprise. Yet, Japanese codes had been compromised. American intelligence led by codereakers in Hawaii had cracked much of the Japanese naval code JN25. The US cleverly confirmed Midway as the target by broadcasting a fake water shortage message from the island 1.

The Japanese intercepted and repeated in coded traffic. Admiral Chester Nimttz moved his carriers into position long before the Japanese arrived, turning Yamamoto’s trap back onto its creators. The plan also called for multiple fleets spread out over hundreds of miles, unable to communicate without revealing themselves.

Nagumo’s carriers, arguably the most important pieces, were left dangerously isolated. Compounding this, Japanese intelligence failed at critical points. A planned reconnaissance over Pearl Harbor was cancelled and a submarine picket line meant to report US carrier movements was deployed too late. The Japanese believe the Americans still had only two operational carriers.

In reality, thanks to a heroic repair effort at Pearl Harbor, the damaged USS Yorktown had been patched up in mere days and rushed back into service. The Americans were bringing three carriers, not two. Even during the pre-battle war games aboard Yamato, flaws were obvious. When a simulated American strike sank two Japanese carriers, umpires simply reversed the result, claiming such an outcome was unlikely.

Victory disease had blinded them to the very possibility of disaster. By 4:30 a.m. on June 4th, Nagumo launched his first strike, 108 aircraft sent to neutralize Midway’s defenses. He kept half his planes armed with torpedoes and armor-piercing bombs in case American ships appeared. The attack hit Midway, but not enough to disable the island’s capability entirely.

Meanwhile, American aircraft launched desperate counterattacks, heroic but ineffective attempts that inflicted no damage on Nagumo’s carriers. Their zero fighters swatted the attackers away with brutal efficiency. At 7 a.m., a message arrived from strike leader Lieutenant Tomaga. There is need for a second attack. The island was not neutralized.

Now Nagumo faced a dilemma. Yamamoto’s strict orders were to keep his reserve strike force ready for American ships. Yet no US fleet had been cited. The attacks from Midway were a nuisance and suggested the island still posed a threat. So at 7:15, Nagumo ordered his reserve aircraft to be rearmed with bombs instead of torpedoes.

A massive undertaking. hanger decks filled with fuel lines, torpedoes, bombs, and fully fueled aircraft in mid swap, creating a volatile environment. Then at 7:28, everything changed. A scout plane launched 30 minutes late reported to an enemy ship cited, and at 8:20, the dreaded confirmation followed. Enemy force accompanied by what appears to be a carrier.

Suddenly, the hunted had become the hunters. The wind across the desert carried the smell of diesel, burning rubber, and something far heavier, something that seemed to cling to every soldier who had survived the chaos of the morning. The Jeep’s engine crackled as it cooled, metal ticking sharply in the tense silence. Its new German occupants worked with a quiet urgency, knowing that the longer they lingered, the greater the chances Allied patrols would circle back.

Hopman Richtor wiped dust from the gauges, tracing the English words with his thumb. To him, this vehicle felt alien yet strangely intuitive. German engineering was precise, measured, almost mathematical. The jeep felt wild, fast, built for sudden movement and rapid strikes. No wonder the Americans relied on it so heavily in their desert maneuvers.

Overberfeld Webble crayons tossed a British ration tin into the back. “If this runs half as well as it looks,” he muttered, we might cross the ridge before the Tommies know we’re gone. RTOR didn’t look up. It will run, and we will not waste the opportunity. Fate dropped at our feet. With the afternoon sun beating down on the metal hood, the two Germans mounted up.

RTOR placed both hands firmly on the wheel. He had driven Kuba wagons, motorcycles, and halftracks, but this was different. The steering felt lighter. The throttle felt eager, almost impatient. He turned the key. The engine jolted awake with a roar that echoed across the dunes. What happened next surprised both men.

The jeep didn’t simply move forward. It leapt. Sand sprayed behind the wheels as the captured machine surged ahead, bouncing over uneven terrain with a confidence that defied its small size. RTOR gripped the wheel tightly, fighting both the speed and the absurd exhilaration rising in his chest. This thing is possessed, Cray shouted over the engine.

No, RTOR replied, barely controlling the skid as they took a sharp bend around a dune. It’s American. They raced toward the far ridge, the sun sinking behind them, the shadow of their jeep stretching long and thin across the desert floor. Far behind the wrecked British supply column lay silent but not forgotten because someone had seen them.

Corporal Thomas Avery. Binoculars pressed against his brow, crouched behind a broken fuel drum. His face was stre with dust and sweat, his heartbeat still racing from the earlier firefight. He had watched the Germans inspect the abandoned jeep. He expected them to destroy it, scuttle it, leave it like everything else on that blasted road, but they had taken it.

And now Avery was watching as the dust trail behind the departing jeep thinned into the horizon. He dropped the binoculars. “This is bad,” he muttered. Not because the jeep held supplies, not because losing it would weaken the column, but because inside that vehicle, tucked between a British map and the torn seat cushion was a coded message meant only for Allied command.

A message he had hidden in haste during the retreat. If the Germans found it, he didn’t want to finish the thought. Avery grabbed his rifle and bolted toward the last operational willies parked near the destroyed Stagghound armored car. The engine coughed twice before roaring to life. He slammed the gear into first and sped forward, determination burning in his eyes. He didn’t need to catch them.

He only needed to follow them long enough to track where they were going. Long enough to retrieve the single slip of paper that mattered more than the jeep itself. Meanwhile, the German jeep climbed the last steep dune before the ridge. The tires spun, then gripped, sending them lurching upward. RTOR shifted to maintain momentum, jaw clenched in concentration.

When they crested the top, the desert opened before them a vast sea of yellow earth stretching endlessly in all directions. Somewhere far beyond lay their lines. Safety, command, recognition for having survived the ambush. That’s it. Cran breathed. Once we reach the escarment, we’ll be invisible from the air. RTOR slowed just enough to navigate the descent, but the jeep still rode the slope like it was born for the terrain.

He couldn’t deny it. The machine was impressive, rugged, dependable, fast, perhaps too fast, because neither soldier noticed a faint shadow briefly passing over the sand behind them. Not a plane, not a cloud, a jeep. Avery kept a safe distance, staying low behind dunes, using the terrain to mask his approach.

The sun was nearly down now, bleeding gold into the horizon. His fuel wouldn’t last more than an hour. His water was nearly gone, but he kept going. He couldn’t allow that message to reach German hands. Night approached. The air cooled. The stars shimmerred with the clarity found only in vast empty deserts.

As RTOR and CR neared the escarment, they slowed for the first time in miles. “Lights off,” RTOR said quietly. “We don’t want to silhouette ourselves.” The jeep rolled forward on momentum alone, unseen, soundless. “Ahead, the cliffs loomed like dark giants. But darkness brings both safety and danger.” As Cran stepped out to guide the vehicle around a boulder, the ground beneath him shifted. He froze.

RTOR whispered sharply. “What is it?” Cran crouched, brushing sand away. Metal glinted beneath the surface. A buried mine. Before he could warn RTOR, the faint crunch of shifting sand behind them broke the silence. Both men turned. A second jeep allied, rolling slowly toward them. silhouetted against the starry sky.

Avery had arrived, but he did not raise his rifle. Not yet. Recklessness would get him killed, or worse, detonate the mine beneath the Germans and send the jeep and the message he needed into oblivion. He stepped forward, hands up. “Don’t move!” he shouted. The Germans spun, startled. The desert fell silent again. Three men, two jeeps, one wrong step from death.

RTOR’s hand hovered near the Luger on his belt. Cran stood rigid, calculating the distance to the mine. Avery kept his rifle low, but ready. Listen, Avery barked. There’s something in that jeep that belongs to us. Hand it over and I’ll walk away. Richtor narrowed his eyes. We took nothing. It’s hidden, Avery replied.

You don’t even know it’s there. Cran shot a quick look at the jeep, confusion flickering across his face. For a moment, no one moved. A single breath could trigger everything. Finally, RTOR exhaled. If we search the vehicle, he said slowly. And find nothing, you leave. Yes. And if we do find something, then you hand it over, Avery said, and we all walk away alive.

It was a fragile deal, thin as paper. But in the desert, survival often depended on fragile things. RTOR nodded once. Together, cautiously, they approached the Jeep. Crayons opened the passenger side panel. RTOR reached beneath the seat cushion. His fingers brushed paper. He pulled out the small folded message.

Avery felt relief surge through him until he saw RTOR’s expression change. What is it? Avery asked sharply. RTOR opened the note and realized it wasn’t a message. It was a map not of Allied positions, not of British supply routes, but of every fuel depot the Germans planned to seize in the next offensive. A betrayal. A setup Avery’s stomach dropped.

Someone had planted the map in the jeep to make it look like Allied intelligence had intercepted it, hoping the Germans would retreat, paranoid their plans were compromised. But now things were far worse because the Germans had the real map. RTOR refolded it slowly. This, he said, voice quiet but firm, changes everything.

Avery raised his weapon instinctively. Don’t even think about taking that back to your lines. Crayons stiffened. RTOR’s expression hardened. The desert waited. Three soldiers, three loyalties. One piece of paper that could alter weeks of fighting. The wind picked up again, carrying sand across their boots.

And in the vast silence of the North African night, the balance of an entire battlefield hung on a single decision.

News

CH2 . How One Radio Operator’s “Forbidden” German Impersonation Saved 300 Men From Annihilation… December 18th, 1944. Inside a frozen foxhole near Bastonia, Corporal Eddie Voss pressed his headset tighter against his frozen ears. Through the crackling static, he heard something that made his blood stop.

How One Radio Operator’s “Forbidden” German Impersonation Saved 300 Men From Annihilation…December 18th, 1944.Inside a frozen foxhole near Bastonia, Corporal…

CH2 . The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball… The other Allied commanders thought he was either lying or had lost his mind. The Germans were laughing, too.

The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball…The other Allied commanders thought he…

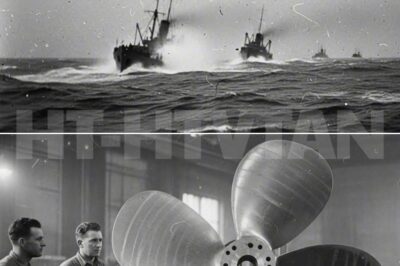

CH2 . How One Cook’s “INSANE” Idea Saved 4,200 Men From U-Boats… March 17th, 1943. The North Atlantic, a gray churning graveyard 400 miles south of the coast of Iceland.

How One Cook’s “INSANE” Idea Saved 4,200 Men From U-Boats…March 17th, 1943.The North Atlantic, a gray churning graveyard 400 miles…

CH2 . How One Sonar Operator’s “Useless” Tea Cup Trick Detected 11 U-Boats Others Missed — Saved 4 Convoys… March 1943, the North Atlantic. A British corvette pitches violently through 20ft swells.

How One Sonar Operator’s “Useless” Tea Cup Trick Detected 11 U-Boats Others Missed — Saved 4 Convoys…March 1943, the North…

CH2 . Luftwaffe Ace Shot Down 5 Americans — Then They Saved His Life and Made Him a Test Pilot… A German test pilot bailed out over enemy territory in 1945, certain the Americans would torture him to death.

Luftwaffe Ace Shot Down 5 Americans — Then They Saved His Life and Made Him a Test Pilot… A German…

CH2 . They Mocked His ‘Medieval’ Crossbow — Until He Killed 9 Officers in Total Silence…… At 3:47 a.m. December 14th, 1944, Private First Class Vincent Marchetti crouched in a bombedout cellar outside Hertgen Forest with a weapon that hadn’t been used in warfare for four centuries. Above him, three German officers conversed 40 yards away, coordinating artillery strikes that would kill dozens of Americans at dawn.

They Mocked His ‘Medieval’ Crossbow — Until He Killed 9 Officers in Total Silence……At 3:47 a.m. December 14th, 1944, Private…

End of content

No more pages to load