Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors…

March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles northwest of Lelay, New Guinea. The oil blackened hand trembled as a Japanese naval officer gripped the splintered remains of what had once been part of the destroyer Arashio’s bridge structure. His uniform soaked with fuel oil and seaater, recording in his mind words that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

Through salt burned eyes, he watched American B-25 Mitchell bombers circle back over the debris field that stretched for miles across the Bismar sea. Oil slicks, burning wreckage, and thousands of men desperately clinging to anything that would float. The convoy that had departed Rabul with such confidence just 2 days earlier was now nothing more than Flatsom, and the survivors were about to discover that their ordeal was far from over.

6,900 soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army’s 51st Division had boarded eight transport ships at Simpson Harbor Rabol on February 28th, convinced they would reinforce Lei and turn the tide in New Guinea. What they encountered instead would shatter every conception of warfare they had been taught, every notion of honor between enemies, and every assumption about American military conduct that Japanese propaganda had instilled in them.

The planning had begun in late December 1942 at Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo. Lieutenant General Hoshi Imamura, commanding the 8th Area Army at Rabbal, faced an increasingly desperate situation in New Guinea. The Japanese convoy was a result of a Japanese Imperial General Headquarters decision in December 1942 to reinforce their position in the Southwest Pacific.

The convoy would consist of eight destroyers escorting eight transport ships carrying the main body of the 51st division elite troops transferred from China. On 28th February 1943, the convoy comprising eight destroyers and eight troop transports with an escort of approximately 100 fighter aircraft set out from Simpson Harbor in Rabal.

The convoy commander, Rear Admiral Masatami Kimura, flew his flag from the destroyer Shiraayuki. A veteran of numerous successful convoy operations, Kimura understood the risks. The 18th Army staff held war games that predicted losses of four out of 10 transports and between 30 and 40 aircraft.

They gave the operation only a 50/50 chance of success. March 1st, 1943. As the convoy rounded the northern coast of New Britain, the first American reconnaissance aircraft appeared. A B-24 Liberator from the 91st Bombardment Group. What the Japanese didn’t know was that their every move had been anticipated. The Allies had detected preparations for the convoy, and naval codereers in Melbourne, FR Umel, and Washington DC, had decrypted and translated messages indicating the convoy’s intended destination and date of arrival.

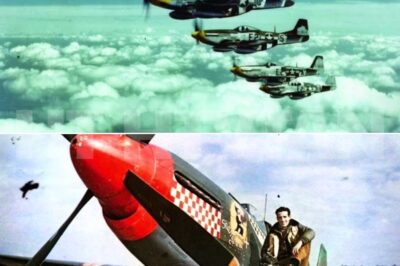

At Fifth Air Force Headquarters, General George Kenny received the news he had been waiting for. For months, his air crews had been perfecting a revolutionary technique. Skip bombing was a low-level bombing technique independently developed by several of the combatant nations in World War II, notably Italy, Australia, Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

It allows an aircraft to attack shipping by skipping the bomb across the water like a stone. Major Paul Papy gun had modified B25 Mitchell bombers, installing up to eight forward-firing 050 caliber machine guns in the nose. Combined with skip bombing techniques, these flying gunships could devastate shipping at close range.

Dawn broke gray and overcast on March 2nd. At 1000 hours, the clouds parted. 29 B7 flying fortresses appeared at high altitude. When a force of 29 B7s hit the convoy, a large merchant vessel was sunk, two others damaged, and a destroyer was set on fire. The first victim was the Kiyoko Maru carrying 1,500 troops and drums of aviation fuel.

B17 pilots reported seeing the transport Kyoko Maru breaking in half and sinking. The 5,493 ton transport exploded in a fireball visible from every ship in the convoy. The destroyers Asagumo and Yukicazi immediately moved in to rescue survivors, pulling oil soaked men from the water.

This act of humanity would soon prove tactically dangerous as they had to reduce speed. The morning of March 3rd dawned clear, perfect flying weather. The convoy, now reduced to seven transports and eight destroyers, had covered nearly 2/3 of the distance to lay. At 1000 hours, death arrived from multiple directions. All of the Japanese plans fell apart, however, at 10:00 a.m.

on March 3rd, 1943 in the Bismar Sea, just off the New Guinea coast from Lei. In the span of about 15 minutes, the Japanese lost World War II. First came B17 at high altitude, drawing Japanese fighters and anti-aircraft guns skyward. Then, while everyone was looking up, 13 Australian bow fighters swept in at mast height, their eight forward-firing guns raking the decks.

Behind them came the modified B-25s approaching so low their prop wash lefts on the water. The skip bombing technique proved devastatingly effective. The bombs would skip over the surface of the water in a manner similar to stone skipping and either bounce into the side of the ship and detonate or submerge and explode next to the ship.

Captain Ed Lana, leading the 90th squadron’s modified B-25s, approached the transport Teomaru at wave height. His forward guns silenced the ship’s anti-aircraft positions. The bombs released from Lana’s B-25 skipped twice across the water before slamming into the Teo Maru’s hull at the water line. The 6,870 ton transport broke in half and sank within minutes.

By 10:15, 15 minutes after the initial attack, all seven transports had been hit and some were sinking. Three of their destroyer escorts had also been badly damaged or had already sunk. The destroyer Shiraayuki, Admiral Kimura’s flagship, took a direct hit that detonated her forward magazine. She disappeared in a massive explosion.

By noon on March 3rd, the Bismar Sea had become a hellscape. Oil fires burned across the surface. The water, thick with bunker fuel, was littered with debris and thousands of men. Soldiers who couldn’t swim, exhausted sailors, wounded clinging to wreckage. Conservative estimates placed over 3,000 men in the water. The four surviving destroyers, Yuki Kazi, Asagumo, Uranami, and Shikinami, began rescue operations.

Some 2,700 survivors were taken to Rabul by the destroyers, but they could only do so much before Allied aircraft returned. At 1,400 hours on March 3rd, the American planes returned with a different purpose. The survivors watched with initial relief as aircraft approached. Surely they were photographing the destruction.

That relief turned to horror as the planes descended to wave height and opened fire. In a controversial move, Allies patrolled the waters for several days, strafing survivors in lifeboats. This was later justified as necessary to prevent the enemy from coming ashore. B25s, A20 Havocs, and bow fighters made repeated passes, their machine guns churning the water into foam.

The tactical justification was clear from the American perspective. These were enemy soldiers who, if they reached shore, would reinforce the Japanese garrison at Lei. As for the strafing of Japanese survivors in the water, they did it keep them from reaching shore and becoming part of the Japanese forces. General Kenny’s orders were explicit.

No Japanese soldier was to reach New Guinea alive. For the Japanese in the water, this violated every concept of honorable warfare. The Bushidto code spoke of treating defeated enemies with dignity. What they experienced shattered these assumptions completely. As darkness fell on March 3rd, American PT boats entered the area.

That night, a force of 10 US Navy PT boats under the command of Lieutenant Commander Barry Atkins set out to attack the convoy. The PT boats systematically hunted survivors through the night. Their search lights swept across the water, followed by machine gun fire. PT43 and PT-150 found the damaged transport Oawa Maru still afloat and torpedoed it, sending more men into the water.

For the Japanese survivors, the night brought additional horrors. Sharks drawn by blood and distressed movements began attacking. Men who had survived the sinking and strafing now faced death from below. Dawn on March 4th revealed the full scope of the disaster. The debris field stretched for 40 mi. Small groups of survivors still dotted the sea, many having spent over 20 hours in the water.

The American aircraft returned with the sunrise. On March 4th, the Allies sent torpedo boats and aircraft to patrol the area. They strafed Japanese survivors and rescue vessels. B25s, A20s, bow fighters, and P38 Lightning fighters systematically attacked anything that moved. The destroyer Asashio, which had remained behind to rescue survivors, became a particular target.

In the morning, a fourth destroyer, Asashio, was sunk when a B7 hit her with a 500 lb, 230 kg bomb while she was picking up survivors from Arashio. She sank quickly, taking rescued soldiers with her. The American justification for the strafing came from both tactical necessity and revenge. As recorded by James Duffy in his book, War at the End of the World, a B17, the double trouble, piloted by Lieutenant Woodro W.

Moore, collided with a zero as seven members of the bomber crew parachuted down several zeros gunned them down as they floated helplessly down. This was observed by crews of other American bombers. This incident had enraged American pilots. General Kenny later called these attacks mopping up operations. For the next several days, American and Australian airmen returned to the site of the battle, systematically prowling the seas in search of Japanese survivors.

As a cudigrass, Kenny ordered his air crew to strafe Japanese lifeboats and rafts. He euphemistically called these missions mopping up operations. A secret March 20th, 1943 report stated, “The slaughter continued till nightfall. If any survivors were permitted to slip by our strafing aircraft, they were a minimum of 30 mi from land in water thickly infested by man-eating sharks.

” Japanese submarines I17 and I26 attempted rescue operations, moving carefully to avoid American aircraft. On the 6th of March, the Japanese submarines I17 and I26 picked up 170 survivors. Two days later, I26 found another 54 and put them ashore at lay. These submarines could only take limited numbers, leaving hundreds behind.

The submarine crews described horrific scenes. Men calling out in darkness, oilcovered survivors too weak to climb aboard. The necessity of choosing who to save. The statistics were staggering. Of 6,900 troops who were badly needed in New Guinea, only about 1,200 made it to Lei. Another 2,700 were rescued by destroyers and submarines and returned to Rabul.

Approximately 3,000 Japanese soldiers and sailors had been killed. American losses were minimal. Allied losses numbered four aircraft and 13 airmen. This 230 to1 casualty ratio was unprecedented in naval warfare. The Battle of the Bismar Sea marked a turning point. As a result of the losses, the Japanese never again risked sending a large convoy into water that was controlled by American aircraft.

Japan would never again attempt to reinforce garrisons by surface convoy within range of Allied aircraft. After the war, Captain Tamichihara, who commanded destroyer Shigura, not present at the battle, interviewed survivors and wrote the most famous Japanese assessment. Never was there such a debacle.

It was the complete opposite of the successful withdrawal operation from Guadal Canal. His interviews with participants revealed the psychological devastation. Japan’s defeat there was unbelievable. The battle showcased revolutionary aerial warfare techniques the Japanese hadn’t anticipated. Skip bombing combined with heavily armed strafer aircraft had turned medium bombers into ship killers.

After Pearl Harbor, December 1941, it was used prominently against Imperial Japanese Navy warships and transports by Major William Ben of the 63rd Squadron, 43rd Bomb Group, Heavy, Fifth Air Force, United States Army Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area Theater during World War II. Major Paul Papy Guns modifications had created flying battleships.

MP Paul Gun of the 90th BS/3rdBG who developed a strafer version of the A20 and B-25 with 8 to 14 forward-firing50 caliber machine guns. These aircraft could devastate anti-aircraft defenses before delivering bombs at point blank range. Not all survivors died in the water. Small groups reached various islands, beginning desperate struggles for survival.

One band of 18 survivors landed on Kirwina where they were captured by PT114. Another made its way to Guadal Canal only to be killed by an American patrol. On Good Enough Island, Australian patrols hunted Japanese survivors. On Good Enough Island between 8 and 14 March 1943, Australian patrols from the 47th Infantry Battalion found and killed 72 Japanese, captured 42, and found another nine dead on a raft.

The Japanese didn’t know until after the war that their convoy had been doomed from the start. The allies had detected preparations for the convoy and naval codereakers in Melbourne FRE and Washington DC had decrypted and translated messages indicating the convoys intended destination and date of arrival.

Every detail, composition, route, timing had been known to the Allies. The Japanese, convinced their codes were unbreakable, had sailed into a carefully prepared trap. For the Japanese military, steeped in Bushidto tradition, the Bismar Sea massacre created a fundamental crisis. The code of Bushido emphasized honor in combat, respect for enemies, dignity in defeat.

The methodical killing of helpless men in water violated every principle they understood. The survivors who returned to Rabul were profoundly changed. They had witnessed American ruthlessness that contradicted all propaganda about American weakness. The image of aircraft systematically hunting men in the water would haunt Japanese forces throughout the Pacific.

Many survivors reported complete loss of faith in victory. If Americans would machine gun helpless men in water, what wouldn’t they do? This psychological impact influenced Japanese decisions to fight to the death rather than surrender. Convinced that capture meant certain execution, the strafing of survivors remains controversial.

Under international law, shipwreck survivors who are helpless should be protected. However, the law was ambiguous about enemy combatants who hadn’t formally surrendered. Japanese forces had committed their own atrocities. the rape of Nan King, baton death march and machine gunning of American air crew in parachutes.

Yet the Bismar sea represented something different. Killing for tactical efficiency rather than cruelty. American veterans defended the actions as military necessity. These weren’t surrendered prisoners, but enemy soldiers heading to reinforce lay. The proximity to shore, some only 10 to 15 miles away, meant many could potentially reach land.

The Bismar sea disaster forced complete reassessment of Japanese strategy. Admiral Minichi Koga, who succeeded Yamamoto as commanderin-chief, recognized that surface vessels couldn’t survive in waters dominated by enemy aircraft. New Guinea was effectively abandoned as indefensible. The psychological impact rippled through Japanese forces.

Units scheduled for transport began experiencing unprecedented desertion rates. The prospect of being caught at sea by American aircraft became a terror surpassing combat itself. For the Americans, the battle proved that air power alone could defeat naval forces. Landbased aircraft, properly equipped and trained, could dominate sea lanes without carriers.

This lesson influenced Pacific strategy for the war’s remainder. After the war, the question of whether the strafing constituted a war crime, was quietly debated, but never prosecuted. The official American position maintained these were enemy combatants who could have reached shore and continued fighting. The absence of prosecution, while Japanese officers were executed for similar acts, reflected Victor’s justice.

Both sides had crossed lines in the Pacific War’s brutal conduct, but only the losers faced judgment. Historians recognize the Battle of the Bismar Sea as a watershed moment in aerial warfare. The statistics tell the story. All eight transports sunk, four destroyers destroyed, approximately 3,000 Japanese killed versus 13 Allied airmen lost.

But beyond numbers, the battle represented transformation of warfare itself. Technology and intelligence had produced casualty ratios that were essentially massacres. The image of aircraft methodically strafing helpless men became emblematic of the Pacific War’s merciless nature. General Douglas MacArthur called it the decisive aerial engagement of the war in the Southwest Pacific.

This assessment proved accurate. Japan never recovered the strategic initiative in New Guinea. The Battle of the Bismar Sea demonstrated that modern warfare had evolved beyond traditional concepts of combat between armed forces. Air power combined with intelligence and technological innovation could produce annihilation rather than victory.

For Japan, it marked the beginning of the end in the Southwest Pacific. Unable to reinforce or supply garrisons within Allied air range, Japanese forces were condemned to isolation and eventual destruction. For America, it proved their transformation from Pearl Harbor’s shocked victims to practitioners of ruthless efficiency.

The same nation that had been stunned by surprise attack had become capable of methodically destroying thousands of enemies. The controversy over strafing survivors reflects war’s moral complexity. Military necessity and humanitarian law collided in the oil sllicked waters of the Bismar Sea.

Both sides learned that in total war, traditional limits would be repeatedly crossed. The Battle of the Bismar Sea stands as one of the most decisive and controversial engagements of World War II. In 3 days, American and Australian air power destroyed an entire Japanese convoy, killing thousands and ending any hope of reinforcing New Guinea by sea.

The shocked Japanese survivors who witnessed Americans strafing helpless men in water carried psychological wounds that never healed. They had encountered an enemy capable of ruthlessness beyond their imagination, shattering assumptions about American weakness and the nature of warfare itself. The battle’s legacy extends beyond its immediate strategic impact.

It demonstrated air power’s ability to dominate sea lanes, the value of intelligence in modern warfare, and the moral ambiguities of total war. The image of aircraft systematically killing survivors remains one of the Pacific War’s most troubling episodes. In the end, approximately 3,000 Japanese died in the waters of the Bismar Sea, not in glorious battle, but in methodical slaughter.

Their shocked survivors returned to spread word of American ruthlessness that would influence Japanese military psychology for the war’s remainder. The Battle of the Bismar Sea proved that in modern warfare, technological superiority could produce annihilation. The Japanese were shocked by American willingness to kill without quarter, learning that their enemies had evolved into something more terrible than propaganda had ever suggested.

That lesson, learned in blood and terror over 3 days in March 1943, would shape the Pacific War’s increasingly brutal character until its atomic conclusion.

News

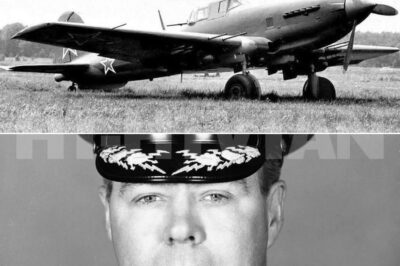

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

CH2 . America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped as North Korean fighters strafe the runway, destroying transports one by one. Enemy armor is twenty miles away and closing. North Korean radar picks up five unidentified contacts approaching from the sea. The flight leader squints through his La-7 canopy.

America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped…

CH2 . Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above Cape Bon, Tunisia.

Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above…

CH2 . Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on April 18th, 1942 fundamentally altered the Pacific Wars trajectory, forcing Japan into a defensive posture that would ultimately contribute to its defeat.

Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on…

CH2 . German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of December 1944, the German war machine, a beast long thought to be dying, had roared back to life with a horrifying final fury. Hitler’s last desperate gamble, the massive Arden offensive, known to history as the Battle of the Bulge, had ripped a massive bleeding hole in the American lines.

German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of…

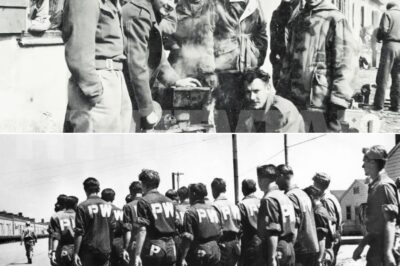

CH2 . German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary, recording words that would have earned him solitary confinement if discovered by his own officers. The Americans must be lying to us. No nation could possess such abundance while fighting a war on two fronts.

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street,…

End of content

No more pages to load