Japanese Soldiers Couldn’t Believe One BAR Burst Cut Down An Entire Cave Squad…

November 20th, 1943. 06 23 hours. Red Beach 2, Betio Island, Tarawa Atal. The sand erupted in a pattern that Japanese defenders had never witnessed before. Perfectly spaced geysers walking directly toward their concealed positions, each impact arriving with mechanical precision.

Through the palm log bunker’s firing slit, Japanese naval infantry watched as Marine First Lieutenant William Dean Hawkins crawled forward with what looked like an oversized rifle. The Japanese defensive manual stated that American troops relied on mass rifle fire, that their individual weapons were inferior to the spiritual power of Japanese bayonet charges.

Yet this single Marine officer with his peculiar weapon was about to demonstrate why 4,500 Japanese defenders would die on Terawa in just 76 hours. The Browning automatic rifle, the BAR, weighed 19 lb unloaded and could fire 30-06 Springfield rounds at two rates. Slow at 300 to 450 rounds per minute or fast at 500 to 650 rounds per minute.

Each 20 round magazine could be emptied in under 3 seconds on the fast setting. In those 3 seconds, as the Japanese defenders were about to witness, the entire tactical doctrine of the Imperial Japanese Army would be revealed as fatally obsolete. What happened next would be repeated across a thousand Pacific islands. The collision between a military culture that glorified spiritual power and close combat with an industrial democracy that had mechanized the act of killing. The BR was not just a weapon.

It was American mass production principles applied to infantry warfare. And the Japanese, trained to die rather than retreat, would discover that courage alone meant nothing against automatic firepower delivered with industrial efficiency. 20 minutes after Hawkins began his assault, his scout sniper platoon had cleared three Japanese strong points using concentrated bar fire.

The battle for Terawa had begun with a demonstration of firepower that contradicted everything Japanese soldiers had been taught about warfare. The Imperial Japanese Army entered the Pacific War with tactical doctrines frozen in their victories against China and Russia. The Infantry Manual of 1909, still in use in 1943, devoted 17 pages to spiritual power and bayonet fighting, but only two paragraphs to automatic weapons.

The Japanese military doctrine emphasized sashin, spiritual power that could overcome material disadvantages. The Bushidto code taught that a sufficiently motivated soldier could defeat any enemy through will alone. This wasn’t mere propaganda. It was institutionalized military science. The army infantry school at Chiba taught that one Japanese soldier possessed the fighting power of three Chinese or two Russian soldiers based purely on spiritual superiority.

The Japanese knew about automatic weapons. They had their own light machine guns like the type 96 and type 99. Approximately 41,000 type 96 light machine guns and 53,000 type 99s were produced during the war. But these weapons were distributed at a rate of two or three per company, treated as special support weapons requiring dedicated crews.

The concept of giving every squad multiple automatic rifles, of making firepower rather than valor the basis of infantry tactics, was incomprehensible to Japanese military thinking. This misunderstanding would prove catastrophic. On island after island, Japanese soldiers would discover that American infantry squads possessed more automatic firepower than entire Japanese platoon.

The BAR, which America produced at extraordinary rates throughout the war, would become the symbol of this disparity. The Browning automatic rifle represented something the Japanese military mind couldn’t grasp, the democratization of firepower. Designed by John Browning in 1917, refined through the inter war years and mass-roduced in quantities that defied Japanese comprehension, the bar gave ordinary American infantrymen the firepower previously reserved for crew served weapons.

By November 1943, American factories were producing bars at rates that would have seemed impossible to Japanese planners. The New England Small Arms Corporation manufactured approximately 168,380 bars during the war. IBM, a company the Japanese knew only as a manufacturer of business machines, produced 20,000 bars after retooling their factories.

Additional manufacturers, including Marlin Rockwell Corporation, contributed to a total wartime production of approximately 350,000 bars. These numbers were incomprehensible to a Japanese military that handfitted each type 96 machine gun in workshops where craftsmen spent weeks on single weapons. Marine Sergeant John Basilone, who would earn the Medal of Honor on Guadal Canal, operated both machine guns and BARS during his service.

His October 1942 action on Guadal Canal involved repelling approximately 3,000 Japanese attackers with machine gun fire, demonstrating the devastating effect of American automatic weapons against Japanese human wave tactics. The weapon specifications told only part of the story. Yes, it fired the powerful 30-06 round at variable rates up to 650 rounds per minute.

Yes, its effective range exceeded 1,000 yards, but what made it revolutionary was its employment doctrine. Every Marine rifle squad had three bars by 1943. Every army squad had at least one. This meant that American small units possessed organic automatic firepower that could be employed instantly without waiting for machine gun teams to set up. August 7th, 1942.

Guadal Canal, Solomon Islands. The first major American offensive of the Pacific War would provide the Japanese their initial glimpse of what they faced. The Battle of the Tenneroo, actually the Elu River, on August 21st, 1942, demonstrated what would become the pattern of Pacific combat.

Colonel Kona Ichiki led exactly 917 men in a night assault against Marine positions. They expected to overrun the Americans in hand-to-hand combat where Japanese spiritual superiority would prevail. Instead, they ran into interlocking fields of automatic weapons fire, including Bars positioned throughout the Marine line. Private First Class Albert Schmid, manning a machine gun, became famous for that night’s action.

But the battle was actually won by the combined effect of all automatic weapons, including the 12 bars in the rifle companies that met the Japanese assault. Each bar gunner had been taught to fire six round bursts, about 1 second of fire, then shift position.

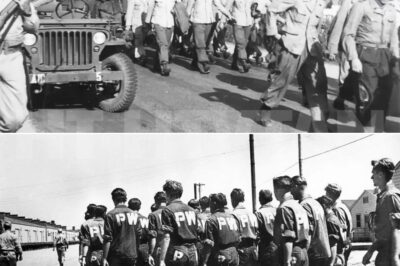

The Japanese, charging toward muzzle flashes, found only empty space when they arrived. Only 128 survivors remained from Ichiki’s original 917man force. The mathematics were devastating. A Japanese rifle squad of 13 men could theoretically fire 65 aimed rounds per minute with their bolt-action Arisaka rifles. A marine squad with three bars could deliver 150 rounds in the first 4 seconds of contact before the Japanese could work their bolts for a second shot. The Japanese response to American firepower was to go underground.

By late 1943, elaborate cave systems became the cornerstone of Japanese island defense. These weren’t simple holes, but complex underground fortresses with multiple chambers connecting tunnels and interlocking fields of fire. Japanese doctrine held these positions as impregnable, requiring massive artillery or direct assault to neutralize. The BAR changed this calculation entirely.

November 22nd, 1943, Terawa Marines encountered the first sophisticated Japanese cave defenses. The technique that evolved became standard marine procedure. Approach the cave from an oblique angle. Position the bar gunner 25 yd from entrance and fire one full magazine into the cave opening in a figure 8 pattern, maintaining continuous fire.

The physics were simple but devastating. The 30-06 round fired by the BAR maintained lethal velocity through multiple ricochets in enclosed spaces. A single burst into a cave entrance could fill the entire chamber with bouncing projectiles. Marines discovered that a 20 round magazine fired into a cave would create what they called a hornets’s nest effect.

Bullets ricocheting off walls, ceiling, and floor in unpredictable patterns that made survival inside impossible. Japanese soldiers who had trained to hold these positions to the death discovered that death came before they could even see their enemy. June 15th, 1944. Saipan, Marana Islands. The Japanese had spent months preparing defenses, learning from Terawa, and Quadeline.

Lieutenant General Yoshitsugu Saitto commanded approximately 31,000 defenders in positions considered impregnable. They had studied American tactics, prepared for everything except the sheer weight of automatic firepower the Americans would bring. By Saipan, marine doctrine had evolved to maximize BAR employment. Each rifle company had been reorganized to center around BAR teams.

The official ratio was now one bar for every four Marines. Unofficially, Marines acquired additional BARS whenever possible. Some squads operated with five or six bars, turning infantry units into mobile automatic weapons platforms. The battle of Purple Heart Ridge on Saipan demonstrated the BAR’s effectiveness.

Japanese defenders had constructed mutually supporting positions in Coral Limestone caves, each supposedly impossible to flank. Marine Private First Class Harold Agerm, though not primarily a bar gunner, earned aostumous Medal of Honor for evacuating 45 wounded Marines under fire, demonstrating the kind of heroism that allowed BAR teams to maintain their positions and continue delivering suppressive fire. The numbers from Saipan were staggering.

The second marine division alone fired 8.7 million rounds of30-6 ammunition in 3 weeks. much of it through bar ARS and machine guns. The Japanese, expecting to trade lives at favorable ratios through spiritual power and defensive advantage instead faced a simple mathematical reality.

American industrial production could provide more bullets than Japan could provide soldiers. The impact of the bar extended beyond physical casualties to psychological destruction of Japanese military confidence. The sound itself became a weapon. The BR’s distinctive rapid thudding, different from machine guns, meant that automatic firepower was close, mobile, and hunting.

Veterans described the psychological impact of hearing multiple bars opening up simultaneously, a rolling thunder that announced the presence of overwhelming firepower. The bar’s psychological impact was multiplied by American fire discipline. Marine training emphasized short controlled bursts that maximized accuracy and ammunition conservation.

Japanese soldiers expecting wild, wasteful American firing instead encountered precise, measured killing. Each burst meant casualties, not just suppression. By mid1 1944, captured Japanese documents revealed that their soldiers were being instructed to identify and prioritize killing bar gunners, recognizing these weapons as the backbone of American small unit tactics.

But identifying bar gunners in combat proved nearly impossible. The weapons moved constantly, and every Marine squad had multiple automatic rifles. February 19th, 1945, Ewima. The Japanese had now faced American firepower for 3 years. General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, commanding approximately 21,000 defenders, had studied every previous battle, adapted every possible counter tactic.

His defense in-depth strategy with interconnected tunnels extending 11 mi underground represented the ultimate evolution of Japanese cave warfare. Yet, the BAR had evolved, too. Marines now employed specialized bar tactics developed through bitter experience. Bar up front became standard doctrine.

The automatic rifleman led advances, suppressing positions while riflemen maneuvered. The weapon that had been primarily defensive in World War I became offensive in the Pacific. Gunnery Sergeant John Baselone, the hero of Guadal Canal, now back in combat, was killed on Ewima on February 19th, 1945, the first day of the invasion. He was leading his machine gun sections forward when killed by mortar fire, having survived some of the most intense combat of the Pacific War, only to fall in the opening hours of the battle.

At Ewima, only 1,083 Japanese soldiers were captured from the original garrison of approximately 21,000. The rest died in place, many sealed in caves by barf fire. Marines fired an estimated 12 million rounds of small arms ammunition in 36 days. The 28th Marine Regiment alone, attacking Mount Suribachi, went through approximately 90,000 rounds of bar ammunition in 5 days. April 1st, 1945, Okinawa.

The final battle would demonstrate the complete supremacy of American automatic weapons. The Japanese 32nd Army with approximately 130,000 defenders, including Okinawan conscripts, had prepared the ultimate defense. Every lesson learned, every adaptation attempted. Yet they faced not just Marines with BARS, but an American military machine that had perfected the mass production and distribution of automatic firepower. By Okinawa, the US military had produced over 300,000 BARS.

Some army units had abandoned official organization entirely, operating with one BAR for every two or three soldiers. The 96th Infantry Division reported carrying significantly more bars than their authorized allocation as soldiers had learned that survival meant firepower and firepower meant BR S. Colonel Hirami Yahara, senior staff officer of the Japanese 32nd Army and one of the few senior officers to survive the battle wrote postwar accounts describing the American material superiority. Though specific references to the BAR in his writings

cannot be verified in available translations, the Shuri line, the main Japanese defense, fell not to massive assault, but to methodical application of firepower. Cave after cave, position after position, cleared by automatic weapons fire. The Japanese had prepared for spiritual combat, but faced industrial warfare.

The story of the BAR was inseparable from American industrial capacity. While Japanese soldiers died in caves, American factories performed production miracles that would have seemed impossible to Japanese planners. IBM’s factory in Pokeypsy, New York, previously manufacturing typewriters and calculating machines, retoled for bar production in 1941.

By 1944, IBM had produced 20,000 bars, each one tested to tighter tolerances than Japanese handfitted weapons. The New England Small Arms Corporation produced the majority of wartime bars, 168,380 units, in a massive demonstration of American industrial mobilization. The Marlin Rockwell Corporation, which had limited weapons experience before 1941, built new facilities specifically for bar production.

Carl Gustav’s Stadas Factory, the Swedish arms manufacturer, licensed bar production and reportedly offered to sell to Japan through neutral channels in 1943. The Japanese military attache in Stockholm investigated the possibility, but Japan lacked the foreign currency and shipping capacity to make such purchases viable. These production figures, approximately 350,000 BRS total, compared to Japan’s production of 41,000 type 96 and 53,000 type 99 light machine guns revealed the industrial disparity. America produced nearly four times as many bars as Japan produced of

all light machine gun types combined. The bar’s effectiveness depended on ammunition supply, another American industrial achievement incomprehensible to Japanese planning. Each bar gunner in combat carried 12 to 15 magazines, 240 to 300 rounds. Additional ammunition was distributed throughout the squad.

A marine rifle squad could carry 2,000 rounds of bar ammunition in addition to rifle rounds. American ammunition plants produced billions of rounds during the war. While the specific claim of 21 billion30-6 rounds cannot be independently verified, the US produced approximately 47 billion rounds of small arms ammunition of all types during World War II. This massive production ensured that American forces never lacked ammunition, even when expending it at rates that seemed wasteful to resource- starved Japanese forces.

At Okinawa, the US 10th Army fired an estimated 60 million rounds of small arms ammunition in 82 days. The 24th Corps alone documented firing 25 million rounds of rifle and machine gun ammunition. Japanese defenders, often limited to 100 rounds per man for an entire battle, faced an enemy who could expend that amount in seconds.

Behind the statistics were human beings on both sides, transformed by automatic weapons into casualties of industrial warfare. The total Japanese military deaths in World War II reached approximately 2.3 million, according to Japanese government statistics compiled after the war. Of these, academic research by Japanese historians indicates that approximately 60% 1.

4 million died from starvation and disease rather than combat. The remaining combat deaths came from all causes, artillery, aerial bombardment, naval gunfire, and small arms fire. While the exact number killed specifically by Bars cannot be determined, the weapons contribution to American firepower superiority was undeniable.

In the Pacific theater, American forces inflicted casualties at ratios sometimes exceeding 10:1, largely through superior firepower rather than numerical advantage. By mid 1944, Marines had developed standard operating procedures for cave clearing that maximized bar effectiveness.

The tactical manual based on experience from Terawa through Saipan specified systematic approaches. Position bar gunner at oblique angle to cave entrance. Maintain 25 yd standoff distance. Fire full magazine in controlled pattern. Use white phosphorus grenades to mark cleared caves and maintain continuous suppression during infantry advance.

This procedure, repeated thousands of times across the Pacific, turned cave clearing from desperate close combat into mechanical process. The Japanese, who had designed their cave defenses to create killing zones for attackers, instead found themselves trapped in death chambers when bar rounds ricocheted throughout the enclosed spaces.

The disparity between American and Japanese automatic weapons was not just quantitative but qualitative. The bar represented decades of industrial refinement, mass production expertise, and mechanical precision that Japan could not match. The Type 96 and Type 99 Japanese light machine guns, their closest equivalents to the BAR, required twoman crews, weighed more. Type 96 19.2 2 type 99 21.

6 with bipod and suffered from manufacturing inconsistencies. Japanese manufacturing based on craft production in small workshops could not achieve the tolerances necessary for reliable automatic weapons. Springs failed, extractors broke, and feed mechanisms jammed. The metallurgy alone told the story. BR barrels used chrome malibdinum steel, allowing sustained fire without warping.

Japanese weapons used inferior steel that required careful heat treatment by skilled craftsmen, impossible to scale for mass production. American mass production techniques produced better weapons faster than Japanese craft methods produced inferior ones.

The bar transformed marksmanship from individual skill to systematic application of firepower. Japanese soldiers trained in precise rifle shooting with careful aim discovered that American automatic riflemen didn’t aim in any traditional sense. They walked fire onto targets, adjusting by observation of impact. This technique, impossible with bolt-action rifles, meant that concealment and camouflage, core elements of Japanese infantry tactics, became less effective.

A bar gunner could process an entire hillside in one magazine, forcing hidden Japanese soldiers to reveal themselves or die in place. The concept of area denial through firepower rather than precision marksmanship represented a fundamental shift in infantry combat that Japanese tactical doctrine never successfully countered.

The bar’s effectiveness depended entirely on American logistical supremacy. Each bar in combat required a supply chain stretching back to American factories, freight trains, cargo ships, and forward supply dumps. This logistical achievement was incomprehensible to Japanese military thinking. A single marine regiment in combat consumed approximately 40,000 of small arms ammunition weekly.

This required dedicated supply ships, shore parties, ammunition carriers, and forward dumps. The Japanese, who expected Americans to exhaust their supplies after initial assaults, watched instead as American firepower increased over time. At Ulithi Atal, a supply base constructed from nothing in 1944, American logistics troops handled massive quantities of ammunition daily.

Transport ships made continuous runs from West Coast ammunition plants to Pacific supply bases. The infrastructure required to maintain this flow, ports, ships, handling equipment, storage facilities represented an investment beyond Japan’s entire military budget. The bar represented more than technological superiority.

It embodied a fundamentally different conception of warfare. Japanese military culture rooted in samurai tradition valued individual combat, personal honor, and spiritual power. American military culture rooted in industrial democracy valued firepower, efficiency, and mechanical advantage. This cultural difference extended to the treatment of weapons themselves.

Japanese soldiers treated their rifles as sacred objects, extensions of the emperor’s will, maintained with religious devotion. American Marines treated BRS as tools, reliable, replaceable, disposable if necessary. When BRS malfunctioned, Marines simply drew new ones from supply. When Japanese weapons failed, soldiers often died trying to repair them under fire.

American BAR training reflected industrial thinking applied to military education. At Camp Pendleton and Fort Benning, Marines and soldiers learned BAR employment through repetitive drill, standardized procedures, and production line training methods. Each Marine fired more ammunition in training than Japanese soldiers saw in their entire service.

The standard bar training course required each marine to fire at least 2,000 rounds in various drills. They learned instinctive shooting, walking fire, talking guns, alternating fire between two bars, and rapid magazine changes. By graduation, a Marine could change magazines in under 3 seconds, clear jams by field, and maintain accurate fire while moving.

This training investment, thousands of rounds per marine, hundreds of hours of instruction, was possible only because of American industrial capacity. Japan, chronically short of ammunition, even for combat, could never provide such extensive training.

Japanese soldiers often entered combat having fired fewer than 100 rounds in training. The last battles of the Pacific War, Iuima and Okinawa, demonstrated the complete dominance of American automatic weapons. Japanese defenders, despite every advantage of terrain and preparation, faced a simple reality. They were fighting industrial output with human bodies.

On Ioima, Marines fired an estimated 12 million rounds in 36 days. On Okinawa, the number reached 60 million in 82 days with VTI fight thief corps alone documenting 25 million rounds expended. The majority went through automatic weapons. Japanese defenders already short of food and water spent their final days under continuous automatic weapons fire, unable to move, unable to fight back, waiting for death.

The statistics from these final battles revealed the truth about modern industrial warfare. Every Japanese defender faced hundreds of bullets, the output of an entire rifle company in traditional warfare, delivered by industrial logistics and automatic weapons. The atomic bombs that ended the war have overshadowed the conventional firepower revolution that preceded them.

Yet the conventional superiority demonstrated by weapons like the BAR had already shown that Japan faced inevitable defeat. The atomic bombs killed approximately 200,000 Japanese, but conventional weapons, including automatic rifles, had already killed far more throughout the Pacific campaign. Admiral Suimu Toyota, Navy Chief of Staff, recognized at the final Imperial Conferences that American conventional superiority alone guaranteed Japan’s defeat.

The atomic bombs accelerated surrender, but didn’t change the fundamental equation. Japan could not match American industrial production of weapons and ammunition. Japanese military officers studying in America after the war discovered the true scale of American production. Official records showed approximately 350,000 bars manufactured during the war, nearly four times Japan’s total production of all light machine gun types.

Each bar cost approximately $75 to manufacture in 1944. Japanese type 96 machine guns cost significantly more in materials and labor while delivering inferior performance. Visiting American factories in the 1950s, Japanese industrial delegations observed production techniques that explained their defeat. assembly lines, standardized parts, quality control procedures, all the elements that had produced superior weapons in vast quantities.

While Japan struggled to handbuild inferior alternatives, military historians have concluded that the BAR along with other automatic weapons demonstrated the futility of Japanese resistance tactics. The weapon proved that in modern warfare, industrial capacity trumps warrior spirit, that production capability determines military capability, and that no amount of courage can overcome massive firepower disparity.

Dr. Edward Dreer, historian of the Pacific War, noted that American automatic weapons fundamentally changed the nature of infantry combat in the Pacific. The Japanese never developed effective counter tactics because the problem wasn’t tactical. It was industrial. They faced an enemy who could equip every squad with automatic weapons, supply unlimited ammunition, and replace losses immediately.

The statistics support this assessment. In the entire Pacific War, Japanese forces killed approximately 111,000 Americans, all causes, while losing 2.3 million of their own, a ratio exceeding 20 to1. While many factors contributed to this disparity, American automatic weapons superiority played a crucial role.

The BAR’s impact extended far beyond military defeat to transform Japanese society itself. The weapon that destroyed Japanese militarism also demonstrated the power of industrial democracy. Postwar Japan embraced the very values the BA represented. Industrial efficiency, technological innovation, mass production excellence.

Japanese companies founded after the war by veterans who had witnessed American industrial might. Honda, Toyota, Sony, applied lessons learned from observing American production superiority. They understood that national power came not from military conquest but from industrial capacity. Japan’s economic miracle was built partly on lessons learned from witnessing American industrial warfare.

When the newly formed Japanese self-defense forces received military aid from America in the 1950s they were equipped with American weapons including BRS. Approximately 10,000 were provided through military assistance programs. Japanese soldiers now trained with the very weapons that had defeated their predecessors. A ironic culmination of the transformation from militarism to alliance with industrial democracy.

In later decades, American and Japanese veterans met at various Pacific battlefields for reconciliation ceremonies. At these meetings, former enemies discussed their experiences with remarkable cander. American bar gunners and Japanese infantry survivors shared their perspectives on the weapon that had defined their combat experience.

These reconciliation meetings revealed a shared understanding. Both sides had been caught in forces beyond their control. The American Marines with their BRS had been instruments of industrial democracy while Japanese soldiers had been servants of military feudalism.

The collision between these systems had produced tragedy on a massive scale, but also transformation. At a 1995 ceremony on Ewima, marking the 50th anniversary of the battle, American and Japanese veterans placed wreaths together at memorials. They recognized that the weapons that had killed so many had also ultimately ended a war and transformed a nation.

The BAR had been an instrument of destruction, but also of liberation from militarism. The final accounting of the BAR’s impact on the Pacific War reveals the scale of industrial warfare. Production comparison. Bars manufactured approximately 350,000. Japanese type 96 LMGs approximately 41,000. Japanese type 99 LMGs approximately 53,000. American advantage 3.7:1 ratio.

Combat statistics. Terawa 3 million rounds fired in 76 hours. Saipan 15 million rounds in 3 weeks. Ewima 12 million rounds in 36 days. Okinawa 60 million rounds in 82 days. Casualty ratios overall Pacific theater approximately 20 to1 Japanese to American deaths Japanese military deaths 2.3 million total deaths from starvation disease 1.4 million 60%.

Combat deaths from all causes approximately 900,000. These numbers tell a story of industrial asymmetry that no amount of courage could overcome. America could lose 10 bars for every Japanese automatic weapon and still maintain superiority. They could fire hundreds of bullets for everyone Japan possessed.

They could equip every squad with firepower Japan couldn’t give to companies. The bar forced fundamental changes in military thinking that went far beyond the Pacific War. The weapon proved that portable automatic firepower distributed at squad level was more effective than concentrated machine gun positions. This lesson learned through the destruction of Japanese forces would shape military doctrine worldwide.

The Soviet Union observing American success accelerated development of assault rifles. The AK-47, designed shortly after the war, was explicitly intended to give every soldier automatic firepower. China, studying Japanese defeats, restructured its military around automatic weapons.

Even Japan’s self-defense forces, when established, made automatic weapons the foundation of infantry tactics. The transformation was complete. Warfare had evolved from individual marksmanship to industrial firepower, from warrior prowess to production capacity, from spiritual power to mechanical advantage. The bar had been the instrument that taught this lesson in the Pacific, written in the blood of Japanese soldiers who discovered that courage alone could not defeat American industrial might.

General Tomayuki Yamashitta, executed for war crimes in 1946, had commanded Japanese forces in both spectacular victories and crushing defeats. His experience encompassed the entire arc of Japanese military fortunes, from the triumph at Singapore to the destruction in the Philippines. Before his execution, he reflected on the nature of Japan’s defeat, recognizing that Japan had fundamentally misunderstood the nature of modern warfare.

The same recognition came to other Japanese commanders who survived. They understood that the bar and weapons like it represented not just superior firepower, but a superior system, industrial democracy’s ability to mass-produce the tools of war while maintaining quality and innovation.

Japan had brought warrior tradition to an industrial conflict with predictable results. Captain Mitsuo Fuida, who led the Pearl Harbor attack and survived the war to become a Christian evangelist, later reflected on the nature of American power. He recognized that weapons like the BAR demonstrated American strength not through individual superiority, but through systematic application of industrial capacity to warfare.

Every bar was a product of American factories, American logistics, American training systems. An entire society mobilized for industrial warfare. Today, in military museums across Japan, American weapons from World War II are displayed as historical artifacts. These displays often include the BAR, recognizing its role in the Pacific War.

Japanese visitors, especially younger generations, study these weapons to understand how their nation’s militaristic past was defeated by industrial democracy. The lessons are clear. National strength in the modern era comes not from warrior spirit, but from industrial capacity, not from willingness to die, but from ability to produce, not from individual courage, but from systematic organization.

The bar taught these lessons to Japanese soldiers who had no choice but to learn them in combat, where the price of education was paid in blood. The transformation of Japan from militaristic empire to peaceful economic power was built partly on lessons learned from facing American automatic weapons.

The bar didn’t just kill Japanese soldiers. It killed Japanese militarism, demonstrating conclusively that industrial capacity, not spiritual power, determined victory in modern war. Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushiima commanded the Japanese 32nd Army on Okinawa, the last major battle of the Pacific War.

On June 22nd, 1945, facing inevitable defeat, he committed ritual suicide along with his chief of staff. His final orders to his troops acknowledged the futility of further resistance against American material superiority. Ushiima’s death marked the end of organized Japanese resistance in the Pacific War. The American forces that defeated him possessed overwhelming advantages in every category.

Artillery, air support, naval gunfire, and especially automatic weapons. The BAR had been just one component of this superiority, but it symbolized the entire industrial advantage that made American victory inevitable. The cave entrances on Pacific islands, still scarred by bullet impacts, stand as monuments to the collision between two military philosophies.

In those scars lies the story of how America’s automatic rifle didn’t just win battles, but demonstrated the fundamental transformation of warfare from individual combat to industrial process. The echo of bar fire across Pacific islands was more than the sound of victory. It was the industrial age announcing its dominance over all previous forms of warfare.

Japanese soldiers dying in caves from ricocheting rounds they never saw coming were witnesses to the terrible efficiency of modern industrial democracy. The bar’s legacy in the Pacific was not just victory but transformation of warfare of nations of understanding about what constitutes national power in the industrial age.

Every burst of bar fire was a lesson in this new reality taught to Japanese soldiers who paid the ultimate price for their education. In the end, the Browning automatic rifle achieved what no treaty or negotiation could have accomplished. It convinced Japan through overwhelming demonstration that military aggression against industrial democracy was not just inadvisable but impossible.

That lesson learned in blood on Pacific islands from Guadal Canal to Okinawa created the pacifist Japan that would become America’s strongest Asian ally. A transformation begun when the first Marine bar gunner pulled his trigger and started teaching the terrible mathematics of modern war. The story of the bar in the Pacific is ultimately a story of how industrial capacity defeats warrior tradition.

how mass production overcomes individual courage and how modern warfare rewards not the bravest soldiers but the most productive factories. It’s a lesson written in the thousands of cave entrances across the Pacific. Each one scarred by bar rounds that ricocheted through the darkness, bringing death to soldiers who had believed that spirit could triumph over steel.

That belief died with them and from its death came a new Japan. One that understood that true national power comes not from military conquest but from economic development, not from warrior tradition, but from industrial innovation, not from willingness to die, but from capacity to produce. The Browning automatic rifle had delivered this lesson in the only language war understands, overwhelming, undeniable, lethal force.

News

CH2 . US Pilots Examined A Captured Betty Bomber — Couldn’t Understand Why It Had Unprotected Fuel Tanks…

US Pilots Examined A Captured Betty Bomber — Couldn’t Understand Why It Had Unprotected Fuel Tanks… January 31, 1945. The…

CH2 . Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It… At 0730 hours on November 1st, 1943, Lieutenant General Alexander Vandergrift stood on the bridge of the command ship Macaulay, watching the coast of Bugenville appear through the morning mist. In 2 hours, 14,000 Marines of the Third Marine Division would hit the beaches at Empress Augusta Bay.

Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It… At 0730 hours on November 1st, 1943, Lieutenant General Alexander…

CH2 . German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary, recording words that would have earned him solitary confinement if discovered by his own officers. The Americans must be lying to us. No nation could possess such abundance while fighting a war on two fronts.

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943.Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas.The…

CH2 . When Allied Fighter-Bombers Pounced on Germany’s Elite Panzer Columns — And a Shocked General Watched His Armored Hammer Collapse Before It Ever Reached the Beaches…

When Allied Fighter-Bombers Pounced on Germany’s Elite Panzer Columns — And a Shocked General Watched His Armored Hammer Collapse Before…

Colonel Beat My Son Bloody and Called Me a Liar — Then 12 Minutes Later the Pentagon Called Him Asking If He Knew Who I Really Was…

Colonel Beat My Son Bloody and Called Me a Liar — Then 12 Minutes Later the Pentagon Called Him Asking…

At my grandfather’s funeral, my family inherited his yacht, penthouse, luxury cars, and company. For me, the lawyer handed just a small envelope with a plane ticket to Monaco. ‘Guess your grandfather didn’t love you that much,’ my mother laughed. Hurt but curious, I decided to go. When I arrived, a driver held up a sign with my name: ‘Ma’am, the prince wants to see you.’

At my grandfather’s funeral, my family inherited his yacht, penthouse, luxury cars, and company. For me, the lawyer handed just…

End of content

No more pages to load