Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It…

At 0730 hours on November 1st, 1943, Lieutenant General Alexander Vandergrift stood on the bridge of the command ship Macaulay, watching the coast of Bugenville appear through the morning mist. In 2 hours, 14,000 Marines of the Third Marine Division would hit the beaches at Empress Augusta Bay.

The Japanese had 110,000 troops at Rabbal, 250 mi to the northwest. Those troops were supposed to stop exactly what Vandergrift was about to do, but they were not coming. Vandergrift had commanded the Marines at Guadal Canal. He knew what happened when you attacked a fortified Japanese position. You bled.

The island fighting in the Solomons had cost thousands of casualties for objectives that barely appeared on a map. Tarawa would prove it again 3 weeks from now. Over 3,000 casualties to take. An island 2 mi long. Rabbal was not 2 mi long. Rabbal was a fortress that made Terawa look like a training exercise.

The Japanese had transformed Rabbal into the most heavily defended position in the South Pacific. They captured it from a small Australian garrison in February 1942, then spent 20 months turning it into an unsinkable aircraft carrier. Simpson Harbor could anchor a 100 ships. Five airfields ringed the harbor. Lakunai and Vunakano were pre-war Australian strips expanded with concrete runways.

Rapopo opened in December 1942 on the coast 14 mi southeast of the town. Tbero was completed in August 1943 halfway between Vunakano and Rapopo. Keravat sat on the north coast 13 mi southwest. Together they had protective revetments for over 400 aircraft and runways that could handle the split comming, heaviest bombers Japan possessed.

367 anti-aircraft guns covered every approach to Simpson Harbor and the airfields. 43 coastal defense guns protected the beaches. 6,000 machine guns were positioned in bunkers and pillboxes. The Japanese army had carved hundreds of miles of tunnels into the volcanic rock, creating underground barracks for 20,000 men, hospitals that could treat thousands of wounded, ammunition dumps holding tens of thousands of tons of explosives, and command centers buried so deep that no bomb could reach them. Over 110,000

Japanese soldiers, sailors, and airmen were based at Rabal by mid 1943. It was the Pearl Harbor of the South Pacific. The Allied plan had always been to capture Rabal. Every strategic document since Guadal Canal pointed to one objective. Take Rabal control. Rabal and you controlled the South Pacific. General Douglas MacArthur called it the key to the theater.

Admiral Ernest King identified it as the primary objective for 1943. The combined chiefs of staff approved operation cartwheel specifically to encircle and capture Rabal by March 1944. But military planners looking at intelligence estimates saw a problem. Taking Rabal would cost more American lives than any battle since the Civil War. The Japanese had learned from Guadal Canal and every island fight in 1942.

They knew the Americans would come with naval gunfire and air superiority. They knew Marines would establish beach heads, so they built defenses designed to turn those advantages into liabilities. The tunnels made strategic bombing ineffective. The anti-aircraft guns meant air support would be murderous to deliver.

The garrison size meant achieving numerical superiority, would require stripping forces from every other theater. Rabbal’s geography offered only three possible landing beaches, all narrow, all covered by interlocking fields of fire from positions the Japanese had spent 18 months fortifying. Intelligence analysts estimated an amphibious assault would cost 30% casualties.

Naval historian Samuel Elliot Morrison would later write that Tarawa, Ewoima, and Okinawa would have faded to pale pink compared to the blood that would have flowed if the Allies had attempted an assault on Fortress Rabal. But in mid 1943, planners were already calculating that 60,000 assault troops would suffer 18,000 killed and wounded, and that assumed everything went right.

Those estimates did not account for Japanese reinforcements from Troo, weather delays or failed naval bombardments. There had to be another way. The first American commander to die attacking Rabal was Brigadier General Kenneth Walker. Walker commanded the fifth Air Force Bomber Command under General George Kenny. He was 44 years old, a theorist who believed strategic bombing could win wars without ground invasions. He had taught at the Airore Tactical School.

Written doctrine. Spent his career arguing that air power properly applied could destroy any target. Rabal was his chance to prove it. Walker flew his first mission over Rabal in September 1942. The raid accomplished nothing. Japanese fighters and anti-aircraft fire drove off the bombers before they could do serious damage. But Walker believed persistence would work.

Hit them again and harder. destroy their aircraft on the ground, sink their ships in the harbor, crater their runways. Eventually, the base would become unusable. On January 5th, 1943, Walker led a daylight bombing raid on Simpson Harbor with six B7 flying fortresses and six B-24 Liberators. The plan was to hit Japanese transports before they could depart for New Guinea.

General Kenny had ordered a dawn raid to avoid Japanese fighters, but Walker delayed it until noon, arguing his bombers needed daylight to form up properly. 12 bombers attacked at high noon against the most heavily defended target in the Pacific. The Japanese were waiting. Fighters from three airfields scrambled to intercept.

Anti-aircraft guns opened fire from positions ringing the entire harbor. Walker’s B7 Flying Fortress, tail number four, 124458, San Antonio Rose, took hits almost immediately. He pressed the attack, leading the formation straight through the anti-aircraft fire. His bombardier scored direct hits on Japanese vessels in the harbor. Then 15 Japanese fighters hit the formation.

Walker’s bomber, already damaged and trailing smoke, could not maneuver. Four to five zeros concentrated on the lead aircraft. Other crews watched San Antonio rose, losing altitude, heading toward the water with its number three engine smoking. The fighters followed it down into the clouds.

Neither Walker, his crew of 10, nor the wreckage was ever found. Walker was awarded the Medal of Honor postumously. President Roosevelt presented it to Walker’s son on March 25th, 1943. The citation praised his conspicuous leadership and personal valor. It did not mention that the raid had failed to stop the Japanese convoy or that strategic bombing alone could not neutralize Rabal.

Walker remains the highest ranking American officer still listed as missing in action from World War II. The second major attempt came in October 1943. By then, Allied forces had captured airfields close enough to mount sustained bombing campaigns. General Kenny planned a massive raid for October 12th. 349 aircraft, the largest strike ever assembled in the Southwest Pacific.

B-25 Mitchells, B-24 Liberators, P38 Lightnings, Australian Bow Fighters, everything the Allies could put in the air. The raid hit all five airfields simultaneously. Bombardias reported devastating results. Kenny’s afteraction report claimed over 100 Japanese aircraft destroyed on the ground.

Multiple fuel dumps set a fire, runways cratered beyond use. Theater command sent congratulatory messages. MacArthur issued press releases declaring Rabal’s air power neutralized. It was not true. Japanese engineers repaired the runways in 36 hours. Most fuel dumps had been empty. The Japanese having moved supplies underground weeks earlier. The aircraft count was wildly exaggerated.

The Japanese had lost fewer than 20 planes, most already damaged and awaiting parts. The raid looked impressive in photographs, but Rabal remained fully operational. Kenny tried again on November 2nd. 72 B-25 medium bombers and 80 P38 fighters hit Simpson Harbor in a low-level attack, strafing and bombing at minimum altitude. It was the most dangerous mission the fifth air force had flown.

The Japanese had reinforced Rabal just one day earlier with 173 carrier aircraft. Elite pilots from the fleet carriers Zuikaku, Shokaku, and Zuiho. Admiral Koga had stripped his combined fleet of its best aviators and sent them to defend Rabal. Those pilots were waiting. The American formation flew into what survivors would call the toughest fight.

the fifth air force encountered in the entire war. Japanese fighters met them at the harbor entrance. Anti-aircraft fire from ships and shore. Batteries created walls of steel. The B-25s pressed their attack, flying so low their propellers threw spray from the harbor water.

They scored hits on several ships and strafed aircraft revetments. Nine B25s did not come back. 10 P38s were shot down. Among the dead was Major Raymond Harold Wilkins, commanding officer of the Eighth Bombardment Squadron, Third Bombardment Group. Wilkins was 33 years old from San Bernardino, California. He had flown 86 previous combat missions.

On his 87th mission over Rabal, Wilkins led his squadron into Simpson Harbor through intense anti-aircraft fire. His aircraft was hit multiple times, but he continued his bombing run, destroying a Japanese destroyer and a 9,000 ton transport. His bomber, trailing smoke and losing altitude, could have turned for home. Instead, Wilkins made a strafing run on a heavy cruiser to draw fire away from his squadron.

His aircraft was shot down and crashed into Simpson Harbor. All six crew members were killed. Wilkins received the Medal of Honor postuously. The November 2nd raid cost 19 aircraft and over 60 men killed or missing. In exchange, the Japanese lost 20 aircraft and suffered minor damage to two cruisers. The raid had not neutralized Rabal. It had barely touched it.

By mid- November 1943, American commanders were looking at a year’s worth of raids and seeing failure. Heavy losses, minimal results. a Japanese base that remained operational no matter how many times they hit it. Strategic bombing had not worked. Not because air crews lacked courage, but because Rabol was too big, too welldefended, and too easy for the Japanese to repair. The ground campaign looked no better.

American and Australian forces had been fighting up the New Guinea coast since January. Every mile caused casualties. The jungle terrain was worse than anything seen in the Solomons. Dense rainforest, steep mountains, disease carrying mosquitoes, impossible swamps. Malaria struck down entire battalions.

Dengi fever caused temperatures that reached 104°. Dissentry weakened men until they could not walk. Tropical ulcers infected the smallest cut and spread until flesh rotted. More soldiers were evacuated for disease than for wounds. at Buna and Gona on the northern Papua coast. The campaign lasted from November 1942 through January 1943.

Australian and American forces fought for 3 months to clear two small coastal villages defended by 6,500 Japanese troops. The Allies committed 13,000 soldiers. Thousand became casualties. Over 7,000 Japanese were killed. The fighting was close-range, brutal, desperate. Japanese bunkers built from coconut logs absorbed 30 caliber bullets.

Flamethrowers became the only effective weapon. Men fought handto hand in swamps and jungles. Bodies lay unburied for weeks in tropical heat. The smell of death permeated everything. When Buuna finally fell in January, American commanders realized they had stumbled into a new kind of warfare. The Japanese would not retreat. They would not surrender.

Every position had to be taken by direct assault against defenders who fought until killed. If Buuna cost 3,000 casualties for two villages, what would Rabal cost? At Nassau Bay on the New Guinea coast in late June 1943, American forces from the 41st Infantry Division landed to support Australian operations against Salamawa. The landing was supposed to be unopposed. Intelligence reported the beach was undefended. The intelligence was wrong.

Japanese forces contested the landing. The Americans got ashore but spent weeks fighting through jungle and swamps to link up with Australian units. What planners thought would take days took 6 weeks. Casualties mounted not from major battles, but from constant small unit actions, ambushes, snipers, and disease.

At lay in early September 1943, MacArthur launched his most ambitious operation yet. The 5003rd Parachute Infantry Regiment jumped onto Nadzab airfield while Australian 9th Division landed amphibiously at Lei. It was perfectly coordinated. MacArthur himself flew over Nadab to watch the paratroopers jump, standing in the open doorway of a B7 bomber.

Despite staff protests about the danger, the landing succeeded. The airfield was captured. Australian forces pushed inland, but the Japanese 51st division defending Lei did not collapse. They conducted a fighting retreat through jungle mountains toward Finch Halfen. The Australians pursued, losing men to ambushes and exhaustion. Two weeks of operations cost the Australians 400 casualties.

The Japanese lost over 2,000 killed, but many more escaped to fight elsewhere. Lei was captured, but the enemy army remained intact. The pattern repeated across New Guinea. Finch Hoffen fell in October after bitter fighting. The Huon Peninsula was cleared by January 1944, but Japanese forces withdrew in good order. Every objective took longer and cost more than estimated.

Every Japanese unit fought harder than predicted, and every victory simply moved the front line closer to Rabal, where 110,000 Japanese troops waited in the strongest defensive position in the Pacific. Allied planners looking at these campaigns saw mathematics that did not work. If taking a village cost 3,000 casualties and required 3 months, and if capturing an airfield cost 400 casualties, required 2 weeks, then assaulting Rabbal with its five airfields, massive garrison, and prepared defenses would cost casualties

beyond anything the allies had suffered. The numbers were inescapable. The idea that changed everything did not come from a single brilliant staff officer working late one night. It came from years of strategic thinking that stretched back to 1921 when Major Earl Hancock Ellis of the Marine Corps wrote War Plan 712, Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia.

Ellis had proposed that the United States could defeat Japan by capturing key islands while bypassing others, strangling Japanese garrisons by controlling the sealanes. The concept had been refined by Admiral Raymond Rogers in war planan orange of 1911, but those were theoretical plans for a hypothetical war.

In June 1943, as Allied forces fought through the use Solomons toward Rabal, the joint strategic survey committee in Washington began questioning whether capturing every Japanese base made strategic sense. Their analysis noted that assaulting Rabal held small promise of reasonable success given the fortress’s strength.

Committee members argued that if American forces could control the sea and air around Rabal, the base itself became irrelevant. The key advocate for bypassing Rabal was General George Catlet Marshall, Army Chief of Staff. Marshall was 62 years old in 1943. A strategic thinker who saw the Pacific War in terms of logistics and casualty ratios, not glory or conquest.

He had spent the first two years of the war fighting for resources against British demands for European priority. Every division sent to the Pacific was a division unavailable for the planned invasion of France. Every ship committed to island fighting was a ship not carrying supplies across the Atlantic.

Marshall calculated resources the way an accountant calculated budgets. He looked at intelligence estimates for Rabbal and ran the numbers. Assaulting the fortress would require at minimum 60,000 assault troops, probably more like 75,000 with support units. Those troops would come from divisions scheduled for Europe or from units already stretched thin in the Pacific.

Casualties would run 30 to 40% in the first two weeks. That meant 20,000 to 30,000 killed and wounded. Replacing those losses would take months. Training their replacements would take longer. And even if the assault succeeded, Rabbal itself provided no value that justified the cost. It was a base, not a strategic objective.

Capturing it accomplished nothing except denying it to Japan, which could be accomplished by isolation. Marshall presented this analysis to the joint strategic survey committee in June 1943. The committee agreed. Their report noted that assaulting Rabbal held small promise of reasonable success and would seriously delay subsequent operations. They recommended neutralization through air and naval power while advancing through positions that offered less resistance.

But recommendation was not policy. The Joint Chiefs would have to approve it. and the joint chiefs included officers who believed strongly that major enemy positions must be captured, not bypassed. In the Pacific, General George Churchill Kenny, reached the same conclusion from different reasoning.

Kenny commanded the fifth air force under MacArthur. He was 53 years old, an innovator who had pioneered skip bombing, low-level strafing attacks, and other tactical developments. After watching his bombers batter Rabal for months with minimal results, Kenny realized something fundamental. You could not destroy Rabol from the air because the base was too large and too dispersed.

The Japanese had spread their facilities across hundreds of square miles. They had buried critical installations in tunnels. They repaired runways within hours. No amount of bombing would eliminate the base. But Kenny also realized you did not need to destroy Rabal. You just needed to neutralize it. If Allied forces could build airfields within fighter range of Rabal, those fighters could sweep over the Japanese base daily.

Bombers could crater a runways faster than the Japanese could repair them. Fighters could shoot down any transport attempting to land. Submarines and patrol bombers could sink any ship trying to enter Simpson Harbor. The garrison would be trapped, unable to receive supplies, unable to launch aircraft, unable to interfere with Allied operations, defeated without invasion. Kenny took this concept to MacArthur in July 1943.

MacArthur’s initial response was negative. He had been planning to capture Rabal since early 1942. His staff had invested months developing invasion plans. His entire Southwest Pacific strategy pointed toward Rabbal as the culminating objective. Bypassing it felt like retreat. It felt like leaving the job unfinished.

MacArthur told Kenny the idea had merit, but expressed concerns about operational security, Japanese reinforcement capabilities, and what the press would say about avoiding a fight. Kenny persisted. He showed MacArthur projections of what the air campaign could accomplish once Bugenville airfields became operational.

He described how per submarines could blockade Rabal. He noted that the combined fleet was already withdrawing heavy ships from the base. He argued that time spent assaulting Rabal was time not spent advancing toward the Philippines and returning to the Philippines was MacArthur’s obsession. That argument resonated.

By early August, MacArthur had shifted from opposition to reluctant acceptance. He did not endorse bypassing Rabbal enthusiastically. His messages to Washington still emphasized the importance of capturing the base, but he stopped actively fighting the concept and allowed his staff to develop contingency plans for isolation rather than assault.

Admiral William Frederick Haly came to the same conclusion through battlefield experience. Haly commanded the South Pacific area. He had been fighting through the Solomons since taking command in October 1942. He had seen Guadal Canal turn into a six-month bloodbath. He had watched good men die on New Georgia, capturing airfields that could have been bypassed.

He had lost ships, lost aircraft, lost Marines to diseases that spread through jungle camps. On August 15th, 1943, Holsey implemented the first pure bypass operation of the Pacific War. Instead of assaulting the heavily fortified Japanese base on Colombanga in the central Solomons, he landed troops on lightly defended Vela Lavella to the northwest. The operation succeeded brilliantly.

American forces built an airfield on Vela Lavella while the Japanese garrison on Colombanga sat isolated and irrelevant. Six weeks later, the Japanese evacuated Colombanga without American forces firing a shot at the base itself. Holsey had proven the concept worked. In August 1943, the combined chiefs of staff met in Quebec for the quadrant conference.

The gathering brought together American and British military leadership to coordinate strategy across all theaters. The question of what to do about Rabal dominated Pacific discussions. Prime Minister Winston Churchill attended with his chiefs of staff. President Franklin Roosevelt brought Marshall King and General Henry Arnold of the Army Air Forces.

The conference lasted from August 17th through August 24th. Marshall presented the case for bypassing Rabal on August 19th. He had prepared meticulously. He brought maps showing Rabbal’s defenses, intelligence estimates of garrison strength, casualty projections for amphibious assault, and alternative plans for isolating the base. His presentation was methodical, logical, devastating.

He argued that assaulting Rabal would cost more American casualties than the pass allies could afford while achieving no strategic advantage that could not be gained by isolation. The fortress controlled no essential territory. It threatened no vital installations. It existed as a threat only if allowed to operate.

Deny it the ability to operate and it became irrelevant. Admiral Ernest Joseph King, chief of naval operations, supported Marshall. King was 64 years old, abrasive, difficult, brilliant. He had been fighting for Pacific resources against European priorities since Pearl Harbor. He knew exactly how many ships, aircraft, and men were available.

He knew what operations were planned for the central Pacific drive through the marshals and Maranas. He told the combined chiefs bluntly that the navy could not support both the Rabbal invasion and the central Pacific offensive. One operation had to be sacrificed. The choice was stark. Spend resources taking a fortress that achieved nothing strategic or spend those resources advancing toward Japan.

King voted for advancing toward Japan. MacArthur’s representatives at Quebec continued arguing for capturing Rabal. Brigadier General Steven Chamberlain represented Southwest Pacific Area interests. Chamberlain was MacArthur’s operations officer. Intelligent, loyal, committed to his commander’s vision.

He argued that bypassing Rabal would leave a dangerous threat in Allied rear areas. He predicted the Japanese would use Rabal to raid American supply lines. He warned that failing to capture such an important base would be seen as weakness, would damage American credibility would embolden Japanese resistance elsewhere. Marshall countered every argument with casualty figures.

He asked Chamberlain directly. How many marines is Rabal worth? 20,000? 40,000? At what point does the cost exceed the value? Chamberlain had no answer. The question was unanswerable because Rabbal had no strategic value that justified any casualties at all. It was a base. Bases could be isolated. Marshall pressed his advantage.

The British chiefs of staff sided with Marshall. They were fighting in Burma, facing their own resource limitations, watching casualties mount in Italy. They had no interest in seeing American resources consumed in a battle that achieved nothing except denying Japan a base that could be denied through isolation.

Field marshall Alan Brookke, chief of the Imperial General Staff, noted acidly that the Americans seemed capable of losing men taking islands, but less capable of advancing toward strategic objectives. Better to bypass the fortress and keep moving. On August 24th, 1943, the combined chiefs issued their directive. Rabol would be neutralized by air and naval action, but not captured.

Allied forces would seize positions on Bugenville, the Green Islands, and the Admiral T islands to establish airfields within range. These airfields would maintain pressure on Rabbal, prevent reinforcement, interdict supply, and contain the garrison. The fortress would be left to wither.

MacArthur would redirect forces planned for the Rabal invasion toward operations in western New Guinea and eventually the Philippines. Holly would continue advancing through the Solomons, but avoid costly assaults on heavily defended positions. The formal directive reached MacArthur’s headquarters in Brisbane on September 17th.

MacArthur read it in his office overlooking the Brisbane River. His staff waited for his reaction. They had spent over a year planning to capture Rabol. Maps covered the walls showing landing beaches, phase lines, objectives, intelligence files detailed Japanese defenses, logistics plans, calculated shipping requirements, training programs, prepared assault units. All of it was now obsolete.

MacArthur sat silent for several minutes. Then he called in his chief of staff, Major General Richard Sutherland, and told him to begin replanning. The objective was no longer a ball. The objective was the Philippines. Rabol would be bypassed.

Forces designated for the assault would be redirected to operations at Hollandia and Itappé in New Guinea. The schedule would accelerate. They would reach the Philippines months earlier than previously planned. Years later, MacArthur would claim in his memoirs that bypassing strong points had always been his strategy, that he had pioneered the concept, that the joint chiefs had simply confirmed his tactical genius.

The historical record shows otherwise. MacArthur opposed the bypass until the Joint Chiefs ordered it. But MacArthur was intelligent enough to recognize when he had lost an argument and pragmatic enough to turn defeat into advantage. If the joint chiefs wanted bypass operations, MacArthur would give them bypass operations on a scale never imagined. He would leaprog across New Guinea, leaving entire Japanese armies isolated and irrelevant.

The Philippines became his obsession. Rabal became a footnote. What happened in the next 6 months proved the bypass strategy worked better than anyone expected. The test began on November 1st, 1943 when 14,000 Marines of the Third Marine Division landed at Empress Augusta Bay on Bugenville under Lieutenant General Vandergrift’s command. The Japanese garrison at Rabbal tried to interfere.

They dispatched a cruiser force from Tru to attack the landing. Admiral Holsey responded by ordering carrier strikes on Rabal itself. On November 5th, Rear Admiral Frederick Coleman Sherman commanded Task Force 38, built around the carriers Saratoga and Princeton. Sherman was 58 years old, a naval aviator who had been flying since 1917. He knew the risks of sending carriers against a land-based fortress.

Rabbal had over 300 anti-aircraft guns and could launch hundreds of fighters. But Hal’s orders were clear. hit the Japanese fleet before it could reach Buganville. At dawn on November 5th, Sherman launched 97 aircraft from his two carriers. 71 came from Saratoga, 26 from Princeton. The strike package included Dauntless dive bombers, Avenger torpedo bombers, and Hellcat fighters.

They flew 250 mi to Rabal, arrived over Simpson Harbor at first light, and caught the Japanese cruiser force at anchor. The attack lasted 18 minutes. American dive bombers screamed down through anti-aircraft fire and put bombs into six of the seven heavy cruisers in the harbor.

A targetgo was hit by near misses that killed 22 crewmen including her captain. Maya took a bomb in her engine room that killed 70. Moami was set a fire with 19 dead. Takao suffered two bomb hits and 23 killed. Chikuma and the light cruiser Aano were damaged. By the time the American aircraft turned for home, the Japanese cruiser force was crippled.

Sherman lost nine aircraft and 14 airmen. Naval historians would call it Pearl Harbor in reverse, the first successful carrier strike against a heavily defended land base. 1 hour after the carrier strike, 27B24, liberators from General Kenny’s fifth air force hit Simpson Harbor with 58 P38 Lightning escorts, adding to the damage.

By the end of November 5th, the Japanese combined fleet had learned a lesson. Simpson Harbor was not safe. The cruisers limped back to truck. The Japanese Navy never sent another heavy surface ship to Rabal. Without naval support, the Rabbal garrison could not contest the Buganville landing. The Marines established their beach head unopposed. Within 3 weeks, the Marines had built an airfield on Buganville.

On November 9th, Major General Royer arrived to take command of First Marine Amphibious Corps, relieving Vanderrift. Geger was 58 years old, one of the Marine Corps’s pioneer aviators. He had been flying since 1917 and understood how air power could dominate a battlefield.

Under his command, the Bogenville airfield became operational in early December. American bombers immediately began hitting Rabbal from 250 mi away. The second test came in late December when Marines landed at Cape Gloucester on the western tip of New Britain. The operation secured the straight between OPI, New Britain and New Guinea, opening sea lanes for Allied shipping. The Japanese garrison at Rabal tried to reinforce Cape Glouester.

American submarines sank two of three troop transports before they arrived. The third turned back. The Cape Glouester landing succeeded with minimal casualties. By January 1944, Rabal was surrounded. Allied airfields on Bugenville, New Britain, and the Green Islands kept constant pressure on the base.

Fighters swept over Rabal daily, shooting down any Japanese aircraft that attempted to take off. Bombers cratered the runways every night. The Japanese could repair them, but could not use them. Simpson Harbor became a graveyard of sunken ships. Supply convoys stopped attempting to reach the base. The 110,000 troops were cut off. Other American commanders watched what happened at Rabbal and realized the strategic implications.

Admiral Chester Nimmitz commanding the central Pacific area saw the bypass succeed and applied it to the Marshall Islands. Instead of attacking heavily fortified bases at Watt, Maloap, and Mal, he bypassed them entirely and captured lightly defended Quadilain and Anwtok. Bypassed garrisons were isolated, unable to interfere.

MacArthur used the same strategy in New Guinea, bypassing Japanese concentrations at Madang and Wiiwak, landing at Hollandia hundreds of miles west, the Japanese 18th Army found themselves surrounded by Allied airfields with no way to fight back. By March 1944, the bypass strategy had spread across the Pacific theater. Planners no longer assumed every enemy position required capture. They asked different questions.

Can we go around it? Can we isolate it? Can we achieve objectives without fighting for this ground? The answer increasingly was yes. Statistics told the story. In the 12 months before the Rabbal bypass, Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific suffered over 15,000 casualties, capturing positions that provided minimal strategic value.

In the 12 months after, casualties dropped below 8,000, while the rate of advance more than doubled. Forces moved faster, lost fewer men, achieved better results. The character of the Pacific War had changed for the Japanese. Realization came slowly then, all at once. The first indication something had changed came in late November 1943 when Rabal Garrison reported American forces had landed on Buganville but were not advancing toward Rabbal.

Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo assumed it was a diversion. The real attack would come later. They ordered the garrison to prepare for invasion. The invasion never came. December passed. January passed. Americans kept building airfields and bombing Rabal, but never landed troops. By February 1944, Japanese commanders understood they were being bypassed.

110,000 troops, the largest concentration of Japanese forces in the South Pacific, sat in a fortress the enemy had decided not to attack. Vice Admiral Jinichi Kusaka commanded the Southeast area fleet at Rabal. He was 52 years old, a career naval officer who had overseen construction of the airfields, tunnels, and defenses.

He had prepared for the decisive battle when American marines would storm the beaches and the garrison would fight to the last man. He had never prepared for being ignored. Kusaka’s first reaction was confusion. Why bypass such a strategic position? Rabal controlled sea lanes and threatened any allied advance. Leaving it intact seemed like a fatal mistake.

He waited for the invasion he knew had to come. But as weeks turned to months and the only Americans he saw were bomber crews at 20,000 ft, confusion turned to understanding. The Americans did not need to capture Rabal. They had already defeated it. Without ships, Rabbal could not project power. Without aircraft, the airfields were useless.

Without supplies, the garrison could not survive indefinitely. Kusaka ordered troops to plant gardens, grow their own food, prepare for a siege that might last years. He knew the war was lost for Rabol the moment. The last supply convoy turned back in January 1944. Everything after that was waiting.

Other Japanese garrisons watched Rabbal and felt their strategic position collapse. At Trroo, the main fleet base in the Caroline Islands, commanders realized if Americans could bypass Rabal, they could bypass Truk. They began evacuating the fleet westward. At Wiiwac in New Guinea, the 18th Army sat in fortified positions, waiting for attacks that never came while Americans landed 400 m behind them at Hollandia.

At Cavien on New Ireland, the garrison dug in and watched American ships sail past toward other targets. The psychological impact was devastating. For 2 years, Japanese strategy had relied on defending key positions, hold islands, control sea lanes, make every American advance so costly they would negotiate peace. The bypass strategy destroyed that logic.

It did not matter how well you fortified a position if the enemy went around it. It did not matter how many troops you concentrated if those troops could not move. The defensive perimeter Japan had spent two years building was revealed as an illusion. Japanese pilots reported American tactics changing. American ships appeared in places they should not reach. Bombers hit targets that should be out of range.

Marines landed on islands that should be isolated. Americans moved faster than Japanese forces could respond because the Japanese fleet was too damaged, aircraft too few, supply lines too vulnerable. By mid 1944, Japan had lost strategic mobility.

They could defend positions they held, but could not counterattack, could not reinforce threatened areas, could not evacuate troops from bypassed garrisons. Americans controlled sea and air, which meant Americans controlled the pace and direction of the war. The reversal was complete. In early 1943, Japanese commanders believed Rabbal was the key to holding the Southwest Pacific.

By late 1944, Rabbal was a prison. 110,000 troops sitting in tunnels, growing vegetables in volcanic soil, waiting for relief that would never come. Americans had defeated Rabal without firing a shot at it on the ground. They did it by making it irrelevant. The bypass strategy received no formal recognition during the war. There was no ceremony celebrating the decision not to invade Rabal.

No medals were awarded for saving 20,000 lives by choosing not to fight. The joint chiefs issued a directive. Commanders implemented it. The war moved on. General George Marshall returned to Washington after the war and served as Secretary of State, then Secretary of Defense.

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953 for the Marshall Plan that rebuilt Europe. When historians asked about the Pacific War, Marshall would say the decision to bypass Rabal was one of the most important strategic choices of the conflict. He estimated it saved tens of thousands of American lives and shortened the war by months. He never claimed credit for himself.

He said it was a collective decision made by military professionals looking at casualty estimates and choosing the path that preserved lives while achieving objectives. General George Kenny remained in the Pacific until Japan surrendered. He commanded the Far East Air Forces during the occupation, retired in 1951, and wrote his memoirs. In his account, Kenny claimed he had always believed air power could neutralize Rabol without invasion.

He devoted several chapters to describing how the fifth air force bombed the fortress into irrelevance. He mentioned the bypass decision in passing as if it had been obvious all along. Historical records show Kenny argued strenuously for months that air power alone could do the job. And he was right. Admiral William Holsey became a national hero.

He returned home in 1945, was promoted to fleet admiral, retired in 1947. He gave interviews, wrote memoirs, appeared at Navy events. When asked about Rabbal, Haly said bypassing it was common sense once the casualty estimates came in. No sane commander would throw Marines at a fortress when you could go around it.

He praised his staff for working out the details, but took full credit for implementing the first true bypass at Vela Lavella in August 1943. That operation proved the concept worked. General Douglas MacArthur commanded Allied forces until Japan surrendered, oversaw the occupation, later commanded United Nations forces in Korea.

In his memoirs published in 1964, MacArthur devoted considerable space to explaining how he had pioneered the bypass strategy. He wrote that he had always intended to avoid frontal assaults on fortified positions, that leaving enemy forces to wither on the vine was his innovation. He mentioned the joint chief’s directive about Rabbal, but framed it as confirmation of his own strategic thinking. Historical documents show MacArthur opposed the bypass until the joint chiefs overruled him.

But by the time he wrote his memoirs, MacArthur had convinced himself otherwise. Rear Admiral Frederick Sherman, who led the carrier strikes against Rabal on November 5th, continued serving through the war. He commanded carrier groups at Lee, Gulf, and Okinawa, retired as a full admiral in 1947. In 1950, he published a memoir titled Combat Command, which included detailed descriptions of the Rabal raid.

Sherman wrote that attacking a land-based fortress with carriers was the riskiest operation he ever commanded. The success of that raid proved carrier task forces could strike anywhere, anytime, and survive. It changed how the Navy thought about carrier warfare. Sherman died in 1957. His Medal of Honor recommendation for the Rabal raid was downgraded to a Navy cross, but his tactical innovations influenced carrier doctrine for decades.

Vice Admiral Jinichi Kusaka remained at Rabal until Japan surrendered in August 1945. His garrison, isolated for 18 months, suffered catastrophic losses. When Australian forces entered Rabal in September 1940, five, they found approximately 69,000 Japanese soldiers and 20,000 civilian workers still alive.

Over 20,000 had died from starvation, disease, and malnutrition. The garrison had sustained itself better than expected by converting to agriculture. They grew rice, sweet potatoes, and tapioca in fields carved from jungle. They fished, raised chickens, and rationed carefully.

An Australian general at the surrender remarked that Rabal had become like a small independent country. Kusaka was investigated for war crimes, but evidence suggests he was never convicted. Unlike General Hoshi Imamura, who commanded 8th Area Army at Rabal and received a 10-year sentence, Kusaka appears to have avoided prosecution. He returned to Japan, published his memoirs in 1958 under the title Nothing New on the Rabol front.

He died in Kamakura on August 24th, 1972, age 83. In interviews before his death, Kusaka said the worst part of Rabal was not the bombing or the starvation. It was waiting for an enemy who never came. Waiting for reinforcements that never arrived, waiting for a battle that would give their sacrifice. Meaning the battle never happened. Brigadier General Kenneth Walker’s body was never recovered.

He remains listed as missing in action, the highest ranking American officer never accounted for from World War II. His name appears on the tablets of the missing at Manila American Cemetery. The Air Force named Walker Air Force Base in New Mexico after him. It operated from 1947 until 1967. Walker Hall at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama, home of Air University, still bears his name.

His Medal of Honor citation remains a testament to leadership by example. The belief that commanders should share the dangers they order others to face. Major Raymond Wilkins is buried at Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines. His Medal of Honor was presented to his family in 1944.

The citation describes how he led his squadron through the heaviest anti-aircraft fire the fifth air force had encountered, destroyed two enemy vessels, then made a final strafing run to protect his men at the cost of his own life. Wilkins flew 87 combat missions. He died on his 87th mission. His squadron mates said he could have stayed on the ground after 80 missions. He chose to keep flying because he believed leaders led from the front.

The physical remains of Rabbal still exist. The tunnels are there carved into volcanic rock slowly filling with jungle vegetation. The airfields are overgrown, runways cracked and broken, revetments collapsing. Simpson harbor is clear now, wrecks salvaged or left to rust on the bottom.

In 1994, volcanoes near Raba erupted, covering the town in ash, forcing evacuation of the population. The old Japanese base was buried under meters of volcanic debris, preserving it and destroying it simultaneously. There is a memorial at Rabbal. It commemorates Australian soldiers who died defending the town in 1942 and Allied airmen who died attacking it in 1943 and 1944.

There is no memorial to the Japanese garrison that starved there. There is no plaque honoring General Marshall who advocated for bypassing the fortress, or the joint strategic survey committee members who first proposed it, or the thousands of Marines who did not die because someone had the wisdom to choose not to invade.

The strategic lesson was learned and applied across the Pacific. American planners used the bypass strategy at Trrook, Wiiweek, Caviang, and dozens of smaller Japanese bases. Historians estimate the strategy saved over 100,000 American casualties by avoiding unnecessary assaults on fortified positions. It accelerated the Allied advance toward Japan by months.

It forced Japan to defend everywhere while attacking nowhere, spreading their forces thin and making them ineffective. That is how strategy actually changes in war. Not through one brilliant staff officer having a revelation late at night, but through collective analysis by military professionals weighing costs against benefits. Major Earl Hancock Ellis wrote the theoretical framework in 1921.

Admiral Raymond Rogers incorporated it into war plans in 1911. The joint strategic survey committee applied it to Rabal in June 1943. General Marshall advocated for it against MacArthur’s resistance. General Kenny provided the air power component. Admiral Holsey implemented it first at Vela Lavella. Then at Rabbal, the Joint Chiefs made it official policy.

And 110,000 Japanese soldiers sat in a fortress for 18 months, defeated not by battle, but by strategic irrelevance. If you found this story as compelling as we did, please take a moment to like this video. It helps us share more forgotten stories from the Second World War to stay connected with these untold histories. Each one matters.

Each one deserves to be remembered. And we would love to hear from you. Leave a comment below telling us where you are watching from. Our community spans from Texas to Tasmania. From veterans to history enthusiasts, you are part of something special here. Thank you for watching and thank you for keeping these stories alive.

News

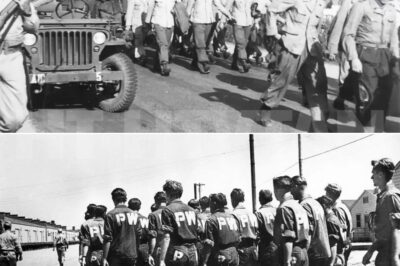

CH2 . German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary, recording words that would have earned him solitary confinement if discovered by his own officers. The Americans must be lying to us. No nation could possess such abundance while fighting a war on two fronts.

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943.Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas.The…

CH2 . When Allied Fighter-Bombers Pounced on Germany’s Elite Panzer Columns — And a Shocked General Watched His Armored Hammer Collapse Before It Ever Reached the Beaches…

When Allied Fighter-Bombers Pounced on Germany’s Elite Panzer Columns — And a Shocked General Watched His Armored Hammer Collapse Before…

Colonel Beat My Son Bloody and Called Me a Liar — Then 12 Minutes Later the Pentagon Called Him Asking If He Knew Who I Really Was…

Colonel Beat My Son Bloody and Called Me a Liar — Then 12 Minutes Later the Pentagon Called Him Asking…

At my grandfather’s funeral, my family inherited his yacht, penthouse, luxury cars, and company. For me, the lawyer handed just a small envelope with a plane ticket to Monaco. ‘Guess your grandfather didn’t love you that much,’ my mother laughed. Hurt but curious, I decided to go. When I arrived, a driver held up a sign with my name: ‘Ma’am, the prince wants to see you.’

At my grandfather’s funeral, my family inherited his yacht, penthouse, luxury cars, and company. For me, the lawyer handed just…

Snow fell softly over the cracked streets of Eastbrook, a forgotten corner of the city where laughter had long gone silent. Streetlights flickered weakly against the biting wind, revealing rows of broken windows, rusted fences, and families doing their best to stay warm. It was Christmas Eve — but here, Christmas was just another cold night.

Snow fell softly over the cracked streets of Eastbrook, a forgotten corner of the city where laughter had long gone…

CH2 . June 4 1942 Battle Of Midway From The Japanese Perspective – military history… Imagine you are Commander Tairo Aayoki, the seasoned air officer, standing on the flight deck of the flagship Akagi at 10:20 in the morning on June 4th, 1942. For 6 months, your fleet has been invincible.

June 4 1942 Battle Of Midway From The Japanese Perspective – military history… Imagine you are Commander Tairo Aayoki, the…

End of content

No more pages to load