How One Tail Gunner’s “Recklessly Savage” Counter-Attack Obliterated 12 Bf 109s in Just 4 Minutes — And Force a Brutal Rethink of Air Combat Tactics Forever..?

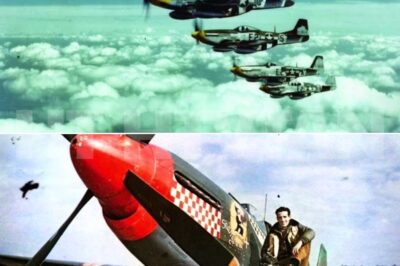

In the early months of 1944, when the European sky had become an enormous killing ground suspended miles above the frozen earth, the most lethal assignment a young American serviceman could receive did not place him in the claustrophobic jungles of the Pacific nor in the mud-choked trenches carved through Italy, but inside a cramped, vibrating, metal enclosure bolted to the very rear of a B-17 Flying Fortress, where a lone gunner faced the terrifying certainty that every mission might be the one that erased him in a flash of cannon fire. At 23,000 feet, far above Germany, where the cold sliced through thick flight suits and oxygen flowed through fragile masks that could betray their wearers at any moment, the tail gunner’s post was less a battlefield position than a suspended execution chamber, yet it was precisely here, on March 6th, that one man chose to reject the passive, by-the-book reaction expected of him and instead rewrite the very terms of his own survival by launching an attack that few would have believed possible.

This drastic choice emerged from a war doctrine already collapsing under its own arrogance. The high command of the Army Air Forces—men who carried an almost zealous faith in the absolute supremacy of strategic daylight bombing and whom history would recall as the Bomber Mafia—had convinced themselves that massive formations of B-17s, heavily armed, heavily armored, and flying at altitude in a rigid defensive box, could penetrate the heart of the Reich in broad daylight without the escort of fighters and force Germany to its knees entirely through aerial destruction. It was a theory fortified by statistics, charts, and confidence rather than by battlefield realities, and by late 1943 those realities were shredding the theory as ruthlessly as enemy cannon shells tore into aluminum fuselages…

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

In early 1944. The most dangerous job in the world wasn’t on the beaches of the Pacific or in the trenches of Italy. It was sitting in a cramped, freezing metal box 23,000ft over Germany. As the tail gunner of a B-17 Flying Fortress, the position was a death sentence, a one-way ticket. But on March 6th, one man decided to rewrite his own obituary by attacking.

This was the great, terrible experiment of the Second World War. The leaders of the Army Air Forces, the men they called the Bomber Mafia, held a deep and powerful belief that massive formations of heavily armed, high flying bombers could fly deep into Germany in broad daylight, unescorted, and win the war all by themselves.

They believed these bombers were in fact, Flying Fortresses. It was a brave theory. But by late 1943 that theory was being torn to shreds. Quite literally, the Eighth Air Force was bleeding on a single infamous raid to Schweinfurt. The force lost 60 bombers in one day. That’s 600 men gone between sunrise and sunset. A tour of duty for a bomber crew was 25 missions. It sounds simple enough.

Yet the brutal, unforgiving math showed that most crews wouldn’t even make it past their fifth. The sky over the Reich wasn’t just a battlefield. It was a meat grinder. And it was chewing up the best young men America had. This wasn’t a failure of courage. It was a failure of doctrine because the sky was full of hunters. The B-17 was a marvel of engineering.

A true titan of the skies. It bristled with thirteen .50-caliber machine guns, earning it that proud name. It was designed to create a 360 degree field of interlocking fire. A box of flying steel that no fighter could penetrate. But it had a blind spot, a fatal flaw.

The Luftwaffe pilots, the German aces flying their Messerschmitt Bf 109s. They were experts. They were fast, agile and armed with devastating 20 millimeter cannons that fired exploding shells. And they had found the flaw. They discovered that the safest, most effective way to kill a fortress was to attack from 6:00 high. Diving down from the rear.

From that angle, the bombers profile was smallest. The closing speed was fastest, and the only man who could shoot back was the tail gunner. And so the most dangerous job in the most dangerous theaters of the war was that one seat. The tail gunner. It was a position of profound loneliness. You were isolated from the rest of the crew, separated by hundreds of feet of fuselage crammed into a space so tight you could barely move. The wind howled through the gaps in the unpressurized metal at 23,000ft.

The temperature was often 30, even 40 degrees below zero. Your guns, your body, your very breath would freeze if you weren’t careful. But the cold wasn’t what killed you. The doctrine was the official by the book. Procedure for a tail gunner was to be reactive.

You were to hold your fire to conserve ammunition, and only shoot after a fighter had committed to its attack, run and was already firing at you. You were, in effect, told to wait to be shot at. This is why the statistics were so grim. In the Eighth Air Force, the casualty rate for a tail gunner killed, wounded or captured was 38%. Nearly 4 in 10 men who sat in that seat did not finish their 25 mission tour.

It was a one-way ticket, a position for men who were either too naive to know the odds or too fatalistic to care. They were told to wait their turn to die, but the man assigned to the B-17 named Hell’s Fury. He just didn’t know how to wait. His name was Staff Sergeant Michael Donovan. And to understand what he did on March 6th, you first have to understand where he came from. He wasn’t a typical by the book soldier.

He was a product of South Boston and a child of the Great Depression. He grew up in a world that was tough and unforgiving. His father worked the docks, a job that demanded strength and grit. His older brother was a Golden Gloves boxer. Southie in the 1920s and 30s was a place of close knit Irish-American families who understood that respect wasn’t given. It was earned.

It was not a place for hesitation. Mike learned a simple philosophy from his father and his brother, one that was practiced in the schoolyards and on the streets. You hit first and you hit hard. He learned a way that gets pounded into you. That waiting is what gets you hurt. Taking action is what keeps you breathing. This wasn’t just a tough guy attitude. It was a survival doctrine.

One he had practiced his entire life. So when Pearl Harbor was attacked, Donovan enlisted in the Army Air Forces. They took one look at his brawling record and tried to put him on a ground crew. He demanded gunnery school during training. His instructors were baffled, and then they were angry.

They wrote him up too aggressive, the report said, too reckless, too willing to expose himself to return fire. Donovan’s response to his instructor became a legend at the training school. Dead gunners, he said. Don’t shoot back. Live ones do. But here’s the crucial detail. Donovan wasn’t just a reckless brawler. He graduated third in his class.

Not just for his spirit, for his speed. His true gift was target acquisition. He could see track and lead a target faster than any other trainee. And his secret was simple. He applied his Southie philosophy to the sky. He didn’t wait for the target to enter his effective firing zone. He hunted them. Miles out before they could even think about getting there. Donovan wasn’t just a gunner.

He was a predator had been waiting his whole life for a real hunt. And in March of 1944, he was about to be assigned to the unluckiest, most cursed bomber in the entire 390th bombardment Group. When Staff Sergeant Michael Donovan arrived at the muddy cold airfield at Framlingham, England, he was assigned to the 390th bombardment Group.

But he wasn’t just assigned to any plane, he was assigned to Hell’s Fury, and it was a bomber with a dark reputation. The plane itself was new, but the crew was already on edge. It had flown only three missions. Two of them were near catastrophic encounters with Luftwaffe fighters.

The plane was known as a fighter magnet, and the tail gun position was considered a magnet for 20 millimeter cannon shells. The position was in fact vacant. The previous gunner, a Sergeant Eddie Morrison, had survived the last mission, he was badly shaken. He’d requested an immediate transfer off the crew, telling his crew Chief Sergeant Frank Murphy, that position is cursed. I’m telling you, Frank.

The next man who sits there dies in the briefing room. When the crew chief asked for a volunteer to take the tail gun on Hell’s Fury. The room went quiet. These men were brave, but they weren’t fools. You don’t volunteer for a cursed seat from the back of the room. A voice cut through the silence. I’ll take it. It was Donovan. The pilot of Hell’s Fury, Captain James Whitmore, was a responsible leader.

He wasn’t about to put a man with a death wish on his crew. He called Donovan into his small office. You know the statistics for that position, Sergeant? Whitmore asked, his voice low. 38%. Don’t finish their tour. It is the highest casualty rate in the entire Air Force. Donovan stood at ease, unblinking. He waited a bit, then replied. Then I’ve got 62% odds, sir. I’ll take them. Whitmore leaned forward, studying the new sergeant.

Why? You got a death wish? No, sir. Donovan said, his voice flat, certain. I just don’t wait for them to shoot me. I shoot first. The captain stared at him, a long, hard look. He was supposed to send this kid to the base psychologist, but he saw the steel in his eyes. Instead, Whitmore just nodded, a small, grim smile on his face. You’re insane, Donovan. You’ll fit right in.

Donovan’s first mission in Hell’s Fury was March 2nd, 1944. The target was the infamous ball bearing factory at Schweinfurt, a target that had broken the back of the Eighth Air Force just months earlier. The mission was a success. He shot down one Bf 109 and officially damaged two others.

But back at Framlingham, the kills weren’t real story. The method was the other Gunners were stunned. Donovan had opened fire the moment the fighters appeared. He was firing long controlled bursts at targets that were still forming up over 800 yards away. This was heresy standard gunnery doctrine drilled into every man was to wait.

Wait until the fighter was at 400, maybe 500 yards. Conserve your ammunition. You only have so much. Donovan had burned through his ammo load at a terrifying rate, but his logic as he explained it to the crew chief later, was brutal and simple. One burst at 800 yards, he said. Cost 20 rounds, but one German fighter breaking his attack pattern that saves a 10,000 pound aircraft and nine lives. Donovan wasn’t counting bullets.

He was counting lives. His second mission was March 4th. This time he refined the tactic. When Gefechtskeil, a battle wedge of German fighters dove at them from 6:00 high. The lead fighter came in hot. Every other gunner on the line would have been desperately tracking that leader. Donovan ignored him. Instead, he laid his sights on the second plane.

The wingman. Why? Because the wingman isn’t focused on evading. He is flying predictably. His eyes glued to his leader, focused entirely on maintaining perfect formation. He’s a stable, predictable target. Donovan’s 50 calibers roared, and the wing man’s plane simply ceased to exist. It disintegrated.

The lead fighter, who had been bracing for returned fire, suddenly saw his partner vanish in a cloud of shrapnel. He was alone. His flank exposed. He panicked. He broke off the attack immediately, rolling hard and diving away. The entire attack. A complex coordinated assault completely fell apart. When Hell’s Fury landed, Sergeant Murphy, the crew chief, was waiting for him. And this time he was furious.

Donovan, what the hell are you doing? He yelled over the sound of the engines winding down. You fired 1600 rounds. That is 80% of your ammo on one mission. We’ve got a whole war left to fight. Donovan just looked at him and said, and we didn’t get hit, did we? I’ll take that trade every single day. It’s this exact kind of practical. Get it done thinking that defined that generation.

It wasn’t about following the rules. It was about getting the job done. If you remember that kind of problem solving, let us know in the comments. We find that this practical wisdom is something that’s sorely missed today. But Donovan wasn’t satisfied. He’d survived. He’d prevented attacks, but he hadn’t maximized his effectiveness because the Germans, he’d scared off.

They just went and attacked another, less prepared bomber in the formation. He hadn’t destroyed them. He needed to think that night, in the damp cold of the Nissen hut barracks. He studied. He didn’t just clean his guns. He analyzed every piece of intelligence he could find on German fighter tactics. He read the after action reports from crews who hadn’t made it back.

He looked at the diagrams of their standard formations and suddenly he saw it. The flaw. It wasn’t in their formations. It was in our response. He realized the lead German fighter wasn’t just an attacker, he was a decoy. He was meant to draw all the defensive fire, while every gunner on the bomber was desperately, instinctively tracking that one obvious threat.

The wingman, the real killers, could slide into the blind spots, line up their shots, and tear the wings right off the fortress. The entire American doctrine was defensive. It was built to react. It waited. The Germans were dictating the terms of every single fight. They. And they alone held the initiative.

Donovan’s mind went right back to the streets of South Boston. What if you reversed it? What if you attacked the attackers? What if you hit them so hard and so fast while they were still forming up, that they were the ones forced to go on the defensive? What if you made them react to you? It was a simple, brutal idea. Born in an alleyway? Stop waiting to get hit.

On March 6th, 1944, on a massive 800 bomber raid to Augsburg, Mike Donovan would get his chance to test that theory, and he would be testing it against the full terrible might of the Luftwaffe. The pre mission briefing for March 6th, 1944 was heavy. The target was a critical aircraft factory in Augsburg, deep in southern Germany.

This would be a long, dangerous flight. 800 B-17s were scheduled to go, which meant the Luftwaffe would throw everything they had at them. Intelligence predicted over 2500 German fighters would rise to meet them. Losses were expected to be in the cold language of the day. Heavy. The air in the Nissen hut was thick with the smell of stale coffee, cigarette smoke and the quiet, metallic tang of fear. Captain Whitmore gathered his crew.

This one’s going to be rough, he said, his voice low and steady. Stay sharp. Call out everything you see. Stay alive. Donovan raised his hand. Permission to try something different, sir. Whitmore’s eyes narrowed. Like what? Donovan. Aggressive fire, sir. I want to engage fighters before they commit to their attack runs. I want to force them to defend before they can attack. The captain frowned.

This went against every rule in the book. That burns ammunition, Sergeant. You’ll be dry before the real fight even starts. You’ll leave this crew defenseless, or I’ll prevent the real fight. Donovan countered, his voice perfectly. Even. Sir, we’ve been playing defense for two years. How’s that 38% casualty rate working out? Maybe it’s time we stopped waiting to get shot.

The room was silent. Every man there knew the grim math Donovan was talking about. Whitmore studied his new tail gunner for a long, hard three seconds. He saw a man who wasn’t just guessing. He had a theory. All right, Donovan, Whitmore said, his voice sharp. You got one mission to prove it.

But if we get shredded because your guns are empty, you’re off this crew and you’re off the gun. Deal? Deal, sir. They took off at oh six 47 hours. The slow, grinding assembly over the green fields of East Anglia. The climb to 23,000ft where the cold began to bite. They crossed the channel. And at oh 824, they entered German airspace.

The routine felt almost mechanical, a long, cold commute until the call came at 0919. It was the waist gunner fighters 6:00, high 12 bandits. Donovan swiveled his twin 50 caliber guns. He saw them 12 Messerschmitt Bf 109s still 2000 yards out. They were forming up a beautiful, deadly collection of silver specks maneuvering into their coordinated attack pattern. Standard procedure was clear wait.

Wait until they commit. Wait until they are at 500, maybe 400 yards. Then engage the lead fighter. Donovan did neither. He opened fire immediately. A long, sustained burst of 50 caliber tracers parked across 2000 yards of empty, frozen sky. The other gunners on the bomber tensed. This was insane. The rounds had almost no chance of hitting at this range.

It was a complete waste of precious ammunition, but the effect was immediate. The German formation, not expecting to be fired upon before their attack had even begun, broke the lead. Pilots, seeing the tracers which looked like giant fiery baseballs zipping past his canopy, instinctively broke. Right. His wingman hesitated.

Their perfect formation instantly dissolving into a confused gaggle of individual planes. The attack was broken before it started. Donovan. Cease fire! Whitmore’s angry voice crackled over the intercom. What the hell are you doing? You’re wasting ammunition. Negative, sir. Donovan replied, his voice impossibly calm. Watch what happens next. The German fighters regrouped, but the entire dynamic of the fight had changed.

They were no longer the confident hunters. They were cautious. Probing, hesitant. They approached again, but not in the aggressive, coordinated dive. They came in piecemeal. The initiative had shifted. A veteran Luftwaffe pilot, angrier than his comrades, broke from the group and dove in, holding his course. Donovan let him come. He let him pass.

500 yards. One 201 109. The range where most gunners would be firing wildly. Donovan waited until the fighter filled his entire gunsight until he could see the details of the engine cowling. Now he didn’t fire a burst. He squeezed the trigger and held it down. A sustained 200 round three second barrage.

It was not a spray of bullets. It was a solid stream of steel. The German pilot tried to break, but it was too late. He flew directly into the wall of tracers. The engine exploded. The aircraft disintegrated. Good. Kill, the radio operator yelled. Donovan just splashed one. Donovan didn’t answer. He was already tracking the next target. He had proven his point, but the fight was far from over.

The remaining 11 fighters, stunned, had broken off for now. Donovan knew they’d be back and they’d be smarter. 15 minutes later, they were. This time 18 fighters. They had learned they weren’t coming from one angle. They split into multiple groups, attacking from 6:00, 7:00, 5:00 and 4:00 simultaneously.

It was a classic Luftwaffe, a tactic designed to overwhelm a bomber’s defenses. To split the gunners attention and guarantee a kill. To make matters worse, Hell’s fury had drifted slightly during the last engagement. The nearest friendly bomber was almost three miles away. They were alone. Donovan was faced with an impossible choice. He couldn’t possibly fight them all.

Standard doctrine said to divide his fire. Try to suppress every group. Donovan did the opposite. He made a cold, calculated decision. He would ignore more than half the attackers waist gunners. He yelled over the intercom, his voice cutting through the rising panic. You’ve got 7:00. Ball turret handle five. I’m holding six.

He was trusting his crew to do their jobs. He would not dilute his own. This was the focus. Fire principle. He centered his guns on the most dangerous group, the six fighters diving directly at his tail. He picked the new leader. Fired. Hit! The fighter exploded. He didn’t wait to admire his work. He didn’t flinch.

His guns swiveled. His mind already on the next leader in the formation. Fired again. Hit another explosion in less than 30s. Three more Bf 109s were falling out of the sky. The remaining nine fighters, stunned by a ferocity they had never encountered from a tail gun, broke off completely. They didn’t just regroup. They fled.

The intercom was silent for a moment and Whitmore’s voice now shaky with awe. Jesus Christ, Donovan! But Donovan was already checking his ammunition. He had burned through more than half his load. He had maybe 800 rounds left and the sky was still full of enemy planes. They would be back. The Germans were furious. They were also professionals. They regrouped.

But this time they didn’t just bring their own squadron. They called in everything. The radar operators voice was tight with dread. Captain. New contacts, many new contacts. 36. No more. The sky went dark. In total, 48 enemy fighters, Bf 109s and the heavily armed Focke-Wulf 190 Butcher Bird were now forming up for a single overwhelming assault on Hell’s Fury. They were alone.

No P-51, no friendly bombers. Just nine men in a tin box facing 48 of the Reich’s best. Donovan checked his ammunition 380 rounds. The math was impossible. Captain Donovan called, his voice still flat. Permission to try something? What is it, Donovan? Attack! There was a long silence on the intercom. Explain.

Whitmore finally said, his voice strained. Sir, they’re forming up for a coordinated assault. They’re still organizing. If we give them two minutes, they’ll hit us from every angle at once. And we are dead. We can’t defend against that. But we can disrupt it. If I engage them now, while there’s still a clumsy mob, I can force them to scatter before they’re ready.

You’ll be out of ammunition in 30s. Whitmore said, the desperation clear in his voice. Then I better make them count, Donovan replied. Sir, defensive tactics don’t work when you’re outnumbered 20 to 1. Our only chance is to hit them now while they’re still vulnerable. Three seconds passed. It felt like an eternity.

Do it, Whitmore said. Donovan didn’t waste a second. The massive German formation was 2000 yards out. A hornet’s nest of wings and crosses still moving into position. Donovan took aim not at a single aircraft. He aimed for the center of the formation. He squeezed his triggers and did not let go. He poured 200 rounds, a solid eight second barrage, not at a plane, but at the empty space where their coordination lived. He was attacking their plan.

The effect was immediate and catastrophic. The sky exploded. Tracers ripped through the heart of the formation. One Bf 109, caught completely by surprise, caught fire and spiraled down. Two others jinking violently to evade the wall of tracers collided with each other. They vanished in a bright orange fireball.

The entire 48 fighter formation disintegrated into chaos. Pilots who had been focused on their attack vectors were suddenly dodging their own men. It was a complete rout, but Donovan knew he hadn’t won. He had only bought them time. He had 180 rounds left. The Germans were stunned, but they were not beaten and now they were angry.

90s later they came back. This time there were no tactics, no formations. Just a furious, vengeful swarm. 12 fighters dove from 6:00 at the same time. Donovan knew he couldn’t stop them all. He had to break their will. He didn’t fire at the closest. He targeted the fighters in the middle of the swarm. The psychological center of the pack.

He fired three short, 30 round bursts into three different aircraft. All three took hits. One exploded. Two others broke off trailing thick black smoke. The remaining nine fighters kept coming. Now inside, 400 yards. The sky lit up. 20 millimeter cannon shells streaked past the cockpit. Hell’s Fury was hit.

The entire aircraft shuddered violently as shells ripped through the rudder. Metal shrieked, but Donovan kept firing. Target burst. Target burst. He was a machine. Another Bf 109 fell. Then another five remaining. 200 yards. Point blank range. Donovan could see the faces of the pilots. Young men just like him. He kept firing.

Two more fighters exploded so close that the debris struck the bomber. Three left. At 100 yards, the survivors, seeing their friends evaporate in front of them, finally broke. They were too close. The risk of collision was now greater than the reward of the kill. Donovan tracked one last fighter pulling away. He squeezed the trigger.

Click the sudden, terrifying silence of empty guns. I’m out! Donovan yelled over the intercom. Tail is dry. I am out. He was defenseless. The remaining 27 German fighters knew it. They had just watched him empty his last belt. They regrouped one final time. They had lost 21 planes to a single bomber. But now the fight was over. They formed up calmly, 2000 yards out for the execution.

They came in slow, methodical. From 6:00 low. Right where Donovan’s guns were. No wasted shots. This was a firing squad. Donovan watched them approach 400 yards. 300, 200. He had no ammunition, no way to defend himself. But he had one weapon left. Psychology. He gripped his handles.

And as the lead German fighter lined up the killing shot, Donovan traversed his guns. He laid his empty sights perfectly on the German’s cockpit and tracked him, unblinking, as if his weapons were loaded and ready. The Luftwaffe ace saw it. He saw the twin 50 calibers, the guns that had just massacred 12 of his friends, swing and point directly at his face.

He knew logically, the gunner must be empty. He knew it. But instinct and the sheer terror of the last four minutes took over. He flinched. He broke formation banking hard, right? The entire German formation, seeing their leader suddenly and inexplicably break off, followed him. The attack was over there, breaking off the ball turret. Gunners voice cracked with disbelief. They’re actually breaking off.

They were. The German formation scattered. They did not return. They were fleeing. Not from bullets. They were fleeing from the ghost of bullets. In four minutes, Michael Donovan’s reputation had become a weapon in its own right, and the air war over Germany would never be the same. The flight to Augsburg continued.

They were still deep in hostile airspace, and Donovan’s guns were silent and dry. But the Germans did not return. The sky, which moments before had been a chaotic swarm of 48 enemy fighters, was now utterly empty. The word had spread over the German radio frequencies. A frantic warning from the surviving pilots. Avoid the B-17. Avoid Hell’s Fury. The tail gunner is insane.

The cost is too high. Donovan’s psychological warfare had worked. They reached the target, dropped their bombs on the aircraft factory, and turned for home. They flew through three more fighter contacts, but none of them engaged. They simply let them pass. Hell’s Fury landed at Framlingham at 1640 seven hours. Nine long hours after takeoff.

As the engines wound down the ground, crews swarmed the aircraft and simply stared. They were horrified. The bomber was a wreck. The tail section was a sieve of shredded aluminum. They counted 47 separate bullet holes and 13 cannon strikes. A hydraulic line was destroyed and the rudder was dangerously cracked. But she had flown.

She had survived. The crew chief Sergeant Frank Murphy, climbed up to the tail gun position. He examined the empty ammunition boxes every single round expended. He found Donovan sitting on the tarmac, leaning against the landing wheel, calmly smoking a cigarette. You used everything, Murphy said. His voice hushed. 2000 rounds.

You fired every bullet we loaded. Donovan took a long drag and looked up. Had to. He replied. 831 00:30:21,700 –> 00:30:23,680 Didn’t have enough to waste any. The debriefing was tense. When Captain Whitmore asked for the tail gunner’s report. Donovan just said, “We were engaged.” The other crew members told the story.

The radio operator who had listened to the German chatter. The waist gunners who had watched the sky fill with smoke and parachutes. “How many did he get?” Whitmore asked the intelligence officer. The officer consulted his notes. He was cross-referencing counts from the other crew members, radio intercepts from German communications, and the visual confirmations from the P-51 escort fighters who had finally caught up near the target.

He looked up, his face pale. “Twelve,” he said. “Twelve confirmed kills. Four probables. Three damaged.” Whitmore looked at Donovan. “You destroyed twelve fighters. On one mission.” “Nineteen, if you count the probables and damaged,” Murphy added, shaking his head. “In four minutes,” the radio operator whispered. “Four minutes of sustained combat.

” The news spread through the bomber group before sunset. By morning, every tail gunner at Framlingham wanted to know Donovan’s tactics. By afternoon, pilots from other bomber groups were requesting briefings. By that evening, Eighth Air Force headquarters had heard the rumor and sent representatives to interview the crew. The next day, Major General Frederick Anderson, the commanding officer of the entire Eighth Bomber Command, arrived personally. He didn’t find Donovan in the officer’s club, telling his story.

He didn’t find him at the bar. He found Staff Sergeant Donovan in the enlisted men’s barracks, methodically and by himself, cleaning his twin .50-caliber machine guns. Standard maintenance. Nothing special. Donovan snapped to attention. “At ease, Sergeant,” Anderson said, looking not at Donovan, but at the gleaming-clean components of the machine gun.

“I’m here to understand what you did yesterday.” Donovan explained his philosophy. It was simple: aggressive fire. Psychological intimidation. He explained that you don’t attack the plane; you attack the formation. You engage during their assembly phase, exploiting the moment of vulnerability before their coordination is set. You force them to react to your plan.

Anderson, a brilliant strategist, listened without interruption. When Donovan finished, the general asked one question: “Can you teach this to the right men?” Donovan hesitated. “Sir, I don’t know if it can be taught. Not to everyone. You need gunners who think like fighters. You need men who see opportunity instead of threat, men who would rather attack than defend.

” “Find them,” Anderson ordered. “I’m authorizing a new special training program. You will develop the curriculum. You will select the candidates. You will transform tail gunner tactics across the entire Eighth Air Force. Effective immediately, you’re reassigned to Training Command.” A flash of conflict crossed Donovan’s face. “Sir… I prefer to stay with my crew.

” Anderson’s voice was blunt, but not unkind. “Your crew doesn’t need you anymore, Sergeant. They’re alive because of what you did. But there are hundreds of other crews who are dying, right now, because their gunners don’t know what you know.

Which is more important, Donovan? Nine men, or nine thousand?” The answer was obvious. Donovan accepted the assignment. He spent the next month developing what became known as the “Donovan Doctrine.” The core principles were simple, but in the world of 1944, they were revolutionary. **First Principle: Seize Initiative.** Never wait for the fighter to attack. Engage during their formation phase.

Force them to respond to your actions, not the other way around. **Second Principle: Psychological Warfare.** Your first burst doesn’t need to destroy the target. It needs to intimidate the formation. Make them cautious. Make them hesitant. Make them second-guess their entire approach. **Third Principle: Focus Fire.** When you’re outnumbered, you must not divide your attention.

Concentrate all your firepower on the most dangerous sector. Trust your other gun positions to handle the peripheral threats. **Fourth Principle: Ammunition Economy Through Aggression.** This was the most radical idea. Donovan proved that firing 30 rounds to scatter 12 fighters was infinitely more “efficient” than firing 300 rounds trying to hit them after they had scattered and started their attack runs. Prevention costs less than reaction.

**And the Fifth Principle: Accept Risk.** This was the hardest one. Tail gunner casualty rates were already high under the old, defensive doctrine. Donovan’s tactics increased a gunner’s individual exposure. But the math was undeniable: it dramatically decreased the bomber’s, and the crew’s, chance of being lost.

The mission, he taught, always mattered more than the man. The Donovan Doctrine faced immediate and stiff resistance. Traditional gunnery instructors, men who had written the book, called it reckless. Command officers, obsessed with logistics, worried about the massive waste of ammunition. Conservative tactics instructors labeled it, flatly, “suicide.” But the statistics didn’t lie.

In March of 1944, before Donovan’s tactics began to spread, the tail gunner casualty rate in the Eighth Air Force averaged a horrifying 38 percent. By June of 1944, after just a few months of widespread adoption of the new aggressive fire doctrine, that rate dropped to 23 percent. Let that sink in. The “suicidal” tactic was saving lives.

It resulted in a 15 percent reduction in casualties for the most dangerous position in the sky. But casualty reduction was only half the story. The real story was in the fighter engagement statistics. In March, German fighters successfully completed 52 percent of their planned attack runs on bomber formations. By June, that completion rate had plummeted to just 27 percent.

This is more than a war story; it’s a powerful lesson in leadership, and how one man’s courage to defy a broken system saved thousands. We believe these stories are vital. If you agree, consider subscribing to the channel. It’s the best and only way to tell us we’re on the right track.

Donovan’s aggressive fire had so effectively disrupted German coordination that more than half of all planned attacks were now being aborted before the fighters even got into firing position. And the final proof? It came from the Germans themselves. After the war, captured Luftwaffe documents and after-action reports revealed the enemy’s perspective.

By the summer of 1944, German training manuals had to be updated. They now included new sections on “American aggressive gunner tactics.” The recommended counter-approach was simple: Avoid. Find easier targets. Do not engage bombers that employ active, aggressive defense from the tail. The psychological battle had been completely reversed. The hunters had become the hunted.

The Donovan Doctrine had given the Flying Fortress its fangs back. Michael Donovan trained 300 tail gunners between March and August of 1944. Each man received two weeks of intensive instruction, live-fire exercises, simulated fighter attacks, and a heavy dose of psychological conditioning.

Donovan was not just teaching them how to shoot; he was teaching them how to think. “Fear happens when you react,” he told every class. “Confidence happens when you act first.” But not every candidate succeeded. The Donovan Doctrine required a specific personality, a trait that couldn’t always be taught. It required a cold decisiveness under extreme pressure, a natural comfort with risk, and the rare ability to maintain focus during absolute chaos.

Roughly 30 percent of the candidates washed out. They couldn’t overcome their hard-wired defensive instincts. They couldn’t embrace the necessary aggression. Those who succeeded, however, became legends. By the war’s end, the graduates of Donovan’s program— just 300 men—accounted for a staggering 43 percent of all tail gunner kills in the entire European theater.

They developed their own techniques, their own innovations. The doctrine evolved beyond its creator. One graduate, a Sergeant Thomas Bailey, destroyed 16 fighters in his first four missions. Another, Sergeant Robert Chen, survived 27 missions without his gun position ever taking a single serious hit. The doctrine didn’t just increase kills; it increased survival through sheer deterrence.

After the war, Donovan’s tactics were studied by military historians and strategists. The principle of “aggressive defense” and “attacking the attack” became incorporated into aerial combat doctrine for multiple nations. The Soviet Union, Britain, and even a rebuilt Germany acknowledged its effectiveness. The concept spread beyond bombers, into fighter escorts and naval aviation.

Today, the core of the Donovan Doctrine is still taught. Pilots learning jet combat, gunners on transport aircraft, even modern missile defense systems… they all incorporate the concept of early engagement to disrupt an enemy’s coordination. But what about the man himself? What became of Michael Donovan? He returned to Boston.

There were no parades for him. He didn’t write a book. He didn’t go on a speaking tour. He, like so many of that greatest generation, put his past in a locked box. He went back to South Boston, picked up his tools, and worked construction for the next 16 years, raising his family. He never talked about the war.

When journalists, piecing together the history of the air war, tracked him down in the 1960s, he declined the interviews. He famously told one reporter, “I did what needed doing. So did 300 other gunners. They’re the real story. Go talk to them.” He died in 1998, at the age of 76. The Boston Globe obituary was short.

It mentioned his Distinguished Service Cross, his 16 years in construction, his wife Margaret, and his three children. One single, sterile paragraph mentioned his war service: “Tail gunner, Eighth Air Force. Developed new tactics.” That paragraph didn’t mention 12 kills in four minutes. It didn’t mention the 300 gunners he personally trained, or the 3,000 lives his doctrine was credited with saving.

It didn’t mention how one South Boston street fighter changed aerial combat for every nation that studied his methods. His funeral was a quiet service at St. Augustine Cemetery. Seventeen people attended. Mostly family, and two old war buddies. The priest who performed the service didn’t know about March 6th, 1944.

He didn’t know about the Donovan Doctrine. He had no idea he was burying a man who had altered the course of aerial warfare. But the gunners knew. The veterans who had passed through Donovan’s aggressive gunner training, they knew. They gathered informally, the night before the service, at a small VFW bar in South Boston.

They raised their glasses, told their stories, and remembered the man who taught them how to shoot first. Thomas Bailey, the ace, now 74 years old, gave the toast. “Mike Donovan never thought he was special,” he said, his voice thick with emotion. “He was just a guy doing his job. But his job saved thousands of us. Every bomber that made it home because German fighters broke off their attack…

every gunner who survived his tour… every mission that succeeded because the enemy was too scared to engage… That’s Mike’s legacy. Not 12 kills. It’s the 3,000 of us who came home.” The Donovan Doctrine remains standard practice. But the story of March 6th, 1944, is more than that. It lasted only four minutes.

It was the moment when one tail gunner, outnumbered 48 to 1, proved that defense must become offense. That reaction must become action. Michael Donovan’s story proves that survival doesn’t come from hiding. It comes from having the courage to face your enemy and making him too scared to fight. This history was preserved because men like Sergeant Bailey shared it.

If this story reminded you of someone, or if you have a piece of your own history to share, we read every single comment. Please, help us keep these vital memories alive. We know your time is valuable, and we are honored you chose to spend it with us. If you enjoyed this story of tactical genius, we’ve placed a video about another incredible wartime innovation right here on the screen.

Thank you for watching.

News

ch2 . How a Farm Kid’s Forbidden Counter-Tactic Turned a Doomed Air Battle Into a Massacre of German Fighters — And Miraculously Save 300 Bomber Crewmen from Certain De@th??

How a Farm Kid’s Forbidden Counter-Tactic Turned a Doomed Air Battle Into a Massacre of German Fighters — And Miraculously…

ch2 . The Rifle the Army Tried to Erase — Until One Defiant Farm Boy Used It to Hunt Down Nine Japanese Snipers Before Dawn,…

The Rifle the Army Tried to Erase — Until One Defiant Farm Boy Used It to Hunt Down Nine Japanese…

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

CH2 . America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped as North Korean fighters strafe the runway, destroying transports one by one. Enemy armor is twenty miles away and closing. North Korean radar picks up five unidentified contacts approaching from the sea. The flight leader squints through his La-7 canopy.

America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped…

CH2 . Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above Cape Bon, Tunisia.

Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above…

CH2 . Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles northwest of Lelay, New Guinea. The oil blackened hand trembled as a Japanese naval officer gripped the splintered remains of what had once been part of the destroyer Arashio’s bridge structure. His uniform soaked with fuel oil and seaater, recording in his mind words that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles…

End of content

No more pages to load