How a Farm Kid’s Forbidden Counter-Tactic Turned a Doomed Air Battle Into a Massacre of German Fighters — And Miraculously Save 300 Bomber Crewmen from Certain De@th??

History often frames the great air battles of World War Two as mechanical duels fought between metal titans, Messerschmitts against Flying Fortresses, engines shrieking across the stratosphere, aluminum crushing against steel in a contest of technology and industrial might. But on the morning of October 14th, 1943, when the winds swept cold across the English airfields and the fog still clung stubbornly to the tarmac, the battle that would define the fate of hundreds of men did not begin at 25,000 feet. It began inside the mind of a nineteen-year-old staff sergeant named Raymond Sullivan, whose knowledge of aerial gunnery was both a burden and a curse.

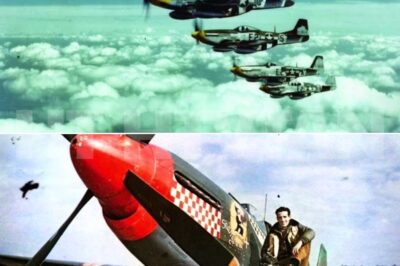

At 8:47 a.m., Sullivan stood rigidly on the control tower observation deck, high enough to see the horizon stretching across the English countryside and close enough to feel the vibration of engines rising beneath him. Below him, a formation of 291 B-17 Flying Fortresses lifted into the air, each aircraft laboring against the heavy October sky, each wing glinting dimly as the sun fought to break through the thick overcast. To an outsider, the scene would have looked like proof that the might of the U.S. Eighth Air Force was overwhelming, unstoppable, a steel storm rolling toward Germany with the confidence of an empire. Pilots waved from their cockpits. Ground crewmen stepped back proudly. Commanders watched with practiced stoicism.

But Sullivan was not an outsider. He was a gunnery instructor who understood the truth hiding beneath the spectacle, a truth formed from calculations, post-mission interviews, and the grim arithmetic of casualties. As he watched those bombers climb in tight formation and disappear into the swelling cloud cover, he felt no pride, no triumph, only a sickening, hollow certainty that half of the men he was watching had already stepped into their coffins. This was not negativity. It was not fear speaking. It was the statistical aftermath of what the Air Force itself had begun calling the Schweinfurt reality.

Just two months earlier, in August of the same year, 376 B-17s had been sent against the German ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt. The mission had been designed as a precision strike, a decisive blow meant to choke the German war machine by targeting its key production point. But the mission’s meticulous planning collapsed under the brutal efficiency of the Luftwaffe. Sixty bombers were torn from the sky in a single afternoon, erupting into fireballs or spiraling helplessly downward, their crews dying in flames or parachuting into captivity. Six hundred men were killed, captured, or lost in a matter of hours. And when the survivors staggered back, dazed, bloodied, and smelling of smoke and burned hydraulic fluid, they all described the same terrifying shift in German tactics that no manual had predicted.

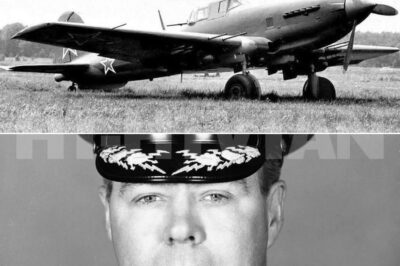

The Luftwaffe had stopped attacking from the rear. American doctrine had long anticipated rear assaults, and the B-17 had been built accordingly, bristling with guns and armor in its tail positions to deny German fighters the easy kills they once enjoyed. But the Germans had evolved. They had abandoned the tail attacks and instead executed a far more deadly strategy: the head-on charge.

From 12:00 high, the Bf 109s and Fw 190s dove straight down the throats of the bomber formations, cannon blazing. It was a brutal collision of approach vectors, a direct assault that transformed every engagement into a contest fought at impossible speeds. This shift exposed a fatal flaw in American doctrine—one Sullivan had recognized instantly and could not un-see. The problem was not courage. It was physics.

A head-on pass between a diving German fighter and a level-flying B-17 created a combined closing speed of more than 600 miles per hour. That number, almost abstract in its enormity, represented a reality that was nearly impossible for the human eye and brain to comprehend in time. It was roughly equivalent to the velocity of a .45-caliber handgun bullet leaving the barrel. And yet American gunners were expected to track, judge, calculate, and fire accurately within that fleeting collision of motion and danger.

For the men stationed in the B-17’s nose and top turret, the window of opportunity was brutally narrow. From the moment the German fighter came into view as a viable target to the fraction of a moment when it flashed past the bomber’s nose, the gunner had exactly three seconds to identify the target, estimate its speed, calculate the necessary deflection, and pull the trigger.

The Army manual presented this sequence as straightforward. The manual urged precision, rationality, composure. But Sullivan knew that in the real world, inside a vibrating bomber, surrounded by noise, adrenaline, and panic, the human brain could not process trigonometry at 600 miles per hour. Expecting a nineteen-year-old gunner to perform a complex calculation under those conditions was like expecting a baseball player to stand calmly in the batter’s box and hit a fastball hurled at lethal force—except the baseball was the size of a Volkswagen, the batter was trapped inside a plexiglass dome, and the pitcher was firing 20-millimeter cannon rounds with fatal intent.

German pilots, especially those led by seasoned aces such as Major Egon Mayer, understood this psychological and mathematical vulnerability better than anyone. They knew American gunners were always behind the curve, always shooting at where the fighter had been, not where it would be. They exploited this flaw with surgical precision, turning every head-on pass into a massacre, every approach into an orchestra of shock, fire, and exploding fuselages.

Standing on the tarmac that October morning, Sullivan felt the weight of this knowledge pressing against him with relentless force. He held a stopwatch in one hand and a notebook in the other, not because he believed the numbers would save anyone today, but because he could not bear to stand idle. When the engines of the final formation disappeared into the distance and the sky fell silent, Sullivan lowered his hands slowly. He had no official solution to offer the men who were now flying toward their fate. He had no sanctioned technique, no approved tactical revision.

But he did have a theory—dangerous, unconventional, forbidden, born not from the manual but from instinct, observation, and a farm kid’s understanding of simple physics.

It was a theory that would soon be whispered among gunners, tested under fire, ridiculed by some, praised by others, and ultimately responsible for the most unexpected achievement of Sullivan’s young life: a tactic that would help bring down thirty-seven German fighters and save more than three hundred bomber crewmen from being erased in the sky.

And yet, when Sullivan first conceived it on that cold deck, he did not know whether it would work, whether it would be allowed, or whether it would be the kind of decision that turned a man into a hero or condemned him to a court-martial for defying doctrine.

All he knew was that the clock had already started, the bombers had already vanished into the clouds, and the Luftwaffe’s head-on storm was already gathering its strength.

What happened next… would test the limits of fear, ingenuity, and defiance in ways Sullivan had never imagined.

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

History often records the great air battles of World War Two as clashes of machines Messerschmitt against Flying Fortresses, aluminum against steel. But on the morning of October 14th, 1943, the battle that mattered most wasn’t taking place at 25,000ft.

It was happening in the mind of a 19 year old staff sergeant named Raymond Sullivan. Standing on a control tower observation deck in England at 8:47 a.m., Sullivan watched a massive formation of 291 B-17 bombers claw their way into the overcast sky. To the casual observer, it looked like the might of the U.S. Eighth Air Force was unstoppable. But Sullivan wasn’t a casual observer.

He was a gunnery instructor, and as he watched those planes disappear into the clouds, he was sick with a quiet, terrible knowledge. He knew that statistically, half of those men were already dead. This grim certainty wasn’t pessimism. It was based on the Schweinfurt reality.

Just two months prior, in August, the Air Force had sent 376 bombers against the German ball bearing factories. It was supposed to be a precision strike. Instead, it was a massacre. 60 bombers were shot out of the sky, and in a single afternoon, 600 men were killed, captured or missing by sunset. The survivors of that August bloodbath all reported the exact same terrifying phenomenon.

The Germans had stopped attacking from the rear, where the B-17s were heavily defended. Instead, the Luftwaffe pilots had engaged in a cold, calculated evolution of tactics. They were attacking from 12:00 high, diving straight at the nose of the bombers. This shift in tactics exposed a fatal flaw in American doctrine, one that Sullivan understood intimately. The problem was simple physics, but the math was brutal.

Consider the geometry of a head on pass, a German Bf 109 fighter diving from above and a B-17 flying level toward it, create a combined closing speed of over 600mph, that is, roughly the speed of a .45 caliber bullet, leaving the barrel of a handgun for the young American gunners sitting in the top turret or the nose.

The window to react was almost nonexistent from the moment the German fighter became a viable target, to the moment he broke away. The gunner had exactly three seconds. In those three seconds, the gunner was expected to do the impossible. The Army training manual, the Bible that Sullivan was forced to teach, instructed gunners to identify the target, estimate speed, calculate the deflection and fire.

But the human brain simply cannot process trigonometry at 600mph. Trying to calculate deflection on a target. Moving that fast is like standing in a batter’s box and trying to hit a major league fast ball. If the baseball was the size of a Volkswagen and firing 20 millimeter cannon shells at your face, German pilots led by aces like Major Egon Mayer, exploited this ruthlessly.

They knew that by the time an American gunner’s brain told his hands where to aim, the fighter was already hundreds of feet past that point. The Americans were firing where the Germans were, not where they would be. So as the engines faded into the distance that October morning, Sullivan stood on the tarmac, gripping a stopwatch and a notebook. He had zero solutions to offer the men flying away from him, but he had a theory.

It was a theory born not in a military academy, but on a chicken farm in Junction City, Kansas. And he knew that if he couldn’t prove it worked, the 291 bombers flying toward Germany were flying into a slaughterhouse. To understand why 600 American airmen vanished on that single day in August, we have to look inside the cockpit of a Focke-Wulf 190.

For the first two years of the war, the Luftwaffe had attacked Allied bombers from the rear. It was standard gentlemanly aerial combat, but it was also dangerous. The B-17 Flying Fortress was named that for a reason. Its tail and waist gunners created a kill zone behind the aircraft. The chewed up German fighters. But in 1942, a German ace named Major Egon Mayer, commander of Jagdgeschwader 2, sat down and studied the blueprints of a captured B-17.

He noticed a blind spot. The nose of the bomber had relatively light armament, and the gunners there had limited visibility. Mayer developed a counter tactic that was as simple as it was devastating. He ordered his pilots to abandon the rear attack. Instead, they would climb to a high altitude circle ahead of the bomber stream and dive from 12:00 high straight into the face of the American formation.

The Germans called this tactic Kopfschuss, literally headshot. American crews just called it murder. And the statistics bore witness to the slaughter. Between January and October of 1943. Mayer’s unit alone destroyed over 200 heavy bombers. Mayer himself was credited with 102 kills. He had turned the B-17s frontal vulnerability into a shooting gallery.

The tragic irony was that the American response to this tactic was actually helping the Germans kill them. The U.S. Army Air Force Gunnery Manual was written for a slower era of warfare. It taught three distinct steps. Acquire the target. Calculate the speed and angle and lead the aircraft.

Leading is the intuitive act of shooting ahead of a moving target, so the bullet and the object arrive at the same place at the same time. It works for duck hunting. It works for clay pigeons. But the manual failed to account for the terrifying arithmetic of 1943. Let’s look at the numbers. Sullivan was scribbling in his notebook while the radio crackled with distress calls.

A B-17 cruises at roughly 180mph. A German fighter in a shallow dive is doing 400mph when they fly directly at each other. Those speeds combine. The closing rate is nearly 600mph. In practical terms, that means the gap between the fighter and the bomber is closing at 850ft per second. Now place yourself in the top turret of a B-17. You spot a speck on the horizon.

Two blinks of an eye. Later, it’s a fighter. You have roughly three seconds before he passes you. The manual says track him. So your brain estimates his speed. You swing your 50 caliber machine guns and you fire where you think he’s going to be. Here is the paradox that was killing these men. The physics of the engagement made the manual obsolete. A 50 caliber bullet takes about 0.

4 seconds to travel the distance to the target. In that tiny fraction of a second 0.4 seconds. 00:07:54:18 – – 00:08:20:20 Unknown The German fighter, moving at 850ft per second, has traveled another 340ft. That is the length of a football field. So the gunner aims perfectly according to his training. He fires up, but by the time his bullets arrive, the German fighter is 340ft closer than the gunners brain calculated. The bullets pass harmlessly behind the tail of the German plane.

The gunner thinks he just missed. So he adjusts. But the angles are changing too fast for the human eye to update. He is essentially shooting at a ghost, firing at a position the German vacated half a second ago. While the American gunner is spraying bullets into empty air. The German pilot has a much easier job.

He doesn’t have to calculate deflection. He is flying straight at a massive, slow moving target. He opens fire at 800 yards, shreds the cockpit, kills the pilots, and dives away before the American gunner can even curse. Sullivan knew this. He didn’t know it because he was a mathematician. He knew it because he was a farmer.

Raymond Sullivan grew up outside Junction City, Kansas. During the hard years of the depression on the Sullivan farm. Survival didn’t depend on B-17s. It depended on 200 chickens. Those birds were the family’s bank account. In the winter of 1936, the temperature dropped and the coyotes came down from the hills.

They were smart, fast and hungry. That winter, Sullivan’s father lost 23 chickens to the predators. In today’s money, that might not seem like much, but in 1936, Kansas, that was $46. Half a month’s income wiped out in blood and feathers. When Sullivan turned 12, his father handed him a Winchester 22 rifle and gave him a job. Stop the coyotes.

If he failed, the family didn’t eat. Sullivan tried the Army method before he ever joined the Army. He tried to track the running coyotes. He tried to swing the rifle, calculate their speed, and lead them. He missed. The coyotes were too fast, and they zigzagged. Then his father told him something that contradicted every instinct of a hunter. Don’t aim at the coyote.

His father explained that trying to track a chaotic, fast moving target was a fool’s errand. Instead, you use the terrain against them. You know the coyote wants to get to the chicken coop. There is a fence line he has to cross. So Sullivan stopped tracking. He would pick a fence post a fixed point in space, and he would aim his rifle at that empty spot.

He would wait. He would watch the coyote running, but he wouldn’t move his gun. He let the animal’s own speed work against it. As the coyotes sprinted toward the coop, it would inevitably cross that fence line. Sullivan would pull the trigger the moment the animal entered his sights. The coyote literally ran into the bullet.

On November 3rd, 1936, Sullivan killed his first coyote using this method. Over the next four years, he shot 47 more. He never missed once. Now, seven years later, standing on a cold airfield in England, Sullivan realized the Luftwaffe had made a fatal error by committing to the headshot attack.

They had stopped behaving like fighter pilots and started behaving like coyotes. They were no longer dog fighting, turning and twisting. They were flying in a straight line toward a specific destination. The nose of the B-17. Their path was predictable. Their speed was constant. Sullivan looked at his stopwatch. Then at the training manual that had sent so many boys to their deaths, the manual said, track the farm logic, said Trap.

He realized that if he could get American gunners to stop chasing the German planes, if he could get them to aim at a fence post in the sky and wait, the Germans would do exactly what the Coyotes did in Kansas. They would run straight into the kill zone. But realizing the solution was one thing, convincing the United States Army that their entire training doctrine was wrong, and that a 19 year old chicken farmer knew better than the generals was a battle that could get him court martialed before he saved a single life. While the generals in Washington

were looking at big maps and moving divisions, Staff Sergeant Sullivan was looking at a wristwatch. It was 10:15 a.m. on the observation deck of the control tower. The air was still and cold, but through the radio headset clamped over Sullivan’s ears. The world was ending. He couldn’t see the bombers.

They were 25,000ft over the German border, but he could hear the ghost of the battle. At first, the radio traffic was disciplined. Call signs, navigation checks, the calm rhythmic chatter of men doing a job. But at 10:27 a.m., the tone changed instantly. Fighters 12:00. Hi. Count 50 plus. Sullivan clicked the stopwatch.

Through the static, he heard the chaotic symphony of the army method failing in real time. He heard the interphones screaming, tracking, tracking. He heard the rhythmic thump, thump, thump of twin 50 caliber Browning machine guns opening up. He watched the second hand on his watch sweep past the ten second mark. Then 20s. According to the doctrine, Sullivan was forced to teach. This should have been a victory.

Hundreds of American guns were pouring thousands of rounds of lead into the sky, but the radio didn’t report kills. It reported panic. They’re coming right through. I can’t hit him. I can’t hit him. Sullivan stopped the watch at exactly 23 seconds. That was the duration of the first German pass and less than half a minute. Thousands of rounds had been expended.

The result? Zero German fighters confirmed down, but the American formation was shattered. Three B-17s were already spiraling toward the Earth. One was burning. Another had its wings sheared off. Sullivan closed his eyes, visualizing the geometry of the slaughter. He realized that the generals had missed the most critical variable in the equation.

Human reaction time versus closing speed. He opened his notebook and looked at the diagram he had drawn. It was the Kansas variable. The generals assumed a gunner was a machine that if you gave him the right inputs, he would produce the right output. But Sullivan knew a gunner was just a boy with a heartbeat. Here was the math.

The Pentagon ignored a German fighter closing at 850ft per second is not a target. It is a blur. If a gunner tries to track it, he is playing a game he cannot win. The fighter moves faster than the heavy turret can swing. But Sullivan saw a different number in his notebook 2.3 seconds.

If a gunner stopped trying to be a sniper and started acting like a trapper, the math flipped. Sullivan calculated that if a gunner picked a fixed point, an empty space roughly 2000ft ahead of the bomber’s nose and held his trigger down, he didn’t need to track anything. Physics dictated that the German fighter had to pass through that point. 00. It was on a rail committed to its dive.

Sullivan calculated that the fighter would hit that specific point in space exactly 2.3 seconds before it reached firing range. That meant if the American gunner just held his fire steady at that imaginary fence post, the German pilot would fly his own airplane into a wall of bullets. The gunner didn’t need to hit the German. The German would hit the bullets. It was brilliant.

It was simple. And as Sullivan listened to the screams on the radio, he knew it was too late for the men dying over Schweinfurt right now. The surviving bombers began to limp home at 1620 three hours. It was a parade of ghosts. Sullivan stood on the tarmac and counted one, two, three gaps where planes should be. The final tally was a gut punch.

62 bombers lost 620 men. Fathers, brothers, sons erased from the roster in a single afternoon. The men who climbed out of the battered planes didn’t look like soldiers anymore. They looked like sleepwalkers. They were covered in sweat. Gun oil and the soot of exploded shells. They had fired until their barrels glowed red.

Yet they had watched their friends die anyway. Sullivan found Sergeant William Morrison in the debriefing room, staring at the floor. Morrison wasn’t a rookie. He was a top turret gunner with 11 combat missions. Before the war, he had been a duck hunter in Oregon. If anyone understood the art of leading a target, it was him. But that day, Morrison looked broken.

How many did you get? Sullivan asked quietly. Morrison looked up, his eyes hollow. Zero. He explained that he had fired 800 rounds. He had done everything the manual said. He calculated deflection. He led the targets and he had missed every single shot. It’s impossible, Morrison whispered. They moved too fast. You can’t track them.

This was the opening Sullivan needed. He leaned in. What if you didn’t have to track them? Morrison looked at him like he was speaking a foreign language. The manual was tracking. That was the whole job. I have a way, Sullivan said. It breaks every rule in the book. But the book just got 600 men killed.

You want to try it? Morrison didn’t hesitate. I’ll try anything. Dying by the manual ain’t much of a comfort. That evening, in a dimly lit briefing room, Sullivan gathered a secret council of six men. These weren’t officers. They were the working class of the Air War. Sergeants and corporals who were tired of losing.

There was Morrison, the duck hunter. There was Staff Sergeant Joseph Brennan, a ball turret gunner who had been a machinist in Detroit. Brennan was a man of precision. He understood that if the mechanics of a machine were wrong, the product would be flawed. He knew the current mechanics of gunnery were broken. And then there was Technical Sergeant Thomas Kowalski.

Kowalski was the hardest sell and the most desperate. Just hours earlier, he had been in his turret when a German 20 millimeter cannon shell ripped through the fuselage of his plane. It had cut his best friend, a waist gunner named Tommy Rodriguez, in half. Kowalski had watched Rodriguez die while German fighters zipped past, untouched by the defensive fire.

He was vibrating with rage and grief. He didn’t care about physics. He wanted revenge. Show me, Kowalski said. Just show me how to kill them. Sullivan stood before a chalkboard and drew a simple diagram. A B-17, a German fighter, and a line connecting them. Forget the fighter, Sullivan told them. The fighter is a distraction.

He drew an X, an empty space representing a convergence point 600 yards in front of the bomber. This is the trap, Sullivan said. You aim here. You don’t move your guns. You press the trigger and you hold it. You create a wall of lead, a dead zone. But how do we know they’ll fly into it? Brennan, the machinist asked. That’s a lot of empty sky. Because they’re greedy, Sullivan answered.

They want the head on shot to get it. They have to fly a straight line to your nose. That line goes right through this point. He tapped the X on the chalkboard. Physics says they have to be there. All you have to do is make sure your bullets are there waiting for them. The room was silent. Sullivan was proposing mutiny against the training manual.

He was telling them to fire blindly into empty air. It sounded insane. It sounded like something a farmer would come up with. Not a soldier. But then Morrison, the duck hunter nodded slowly. It’s a blind. He said, like waiting for a duck to land. You don’t shoot the bird. You shoot the landing spot. Kowalski stood up. I don’t care what it is. If it puts a bullet in a German cockpit.

I’m doing it. Sullivan had his volunteers. Now he just needed to prove that his Kansas variable could actually work. Before the Luftwaffe wiped the Eighth Air Force out of existence. He told them to get some sleep. Tomorrow they were going to the gunnery range to test a theory that could either save the war or get them all court martialed.

The next morning, the air at the ground gunnery range tasted like iron and damp earth. It was a gray, miserable English dawn, the kind that seeps into your bones. But for Sullivan and his six volunteers, the cold was the least of their worries. They were about to conduct an unauthorized experiment with live aircraft. Sullivan had called in a favor to get a target.

He didn’t want a sleeve towed behind a plane that was too slow, too safe. He wanted a predator. He secured the help of Captain James Fletcher, a P-47 Thunderbolt pilot with 41 combat missions under his belt. Fletcher was a man who didn’t scare easy. He had tangled with the Luftwaffe over France and lived to tell about it.

But when Sullivan explained the plan, standing on the wet grass, Fletcher looked at him like he had lost his mind. Sullivan wanted Fletcher to simulate a German suicide run. He was to take his P-47 up to 5000ft, dive at maximum speed, directly at a B-17 parked on the ground, and break off at the last possible second. And what what are your gunners going to do? Fletcher asked, eyeing the nervous volunteers. They’re not going to track you, Sullivan said calmly.

They’re not going to aim at empty space and wait for you to fly into it. Fletcher laughed, a sharp, humorless bark. That’s insane, Sergeant. If they don’t track me, they won’t hit me. And if they don’t hit me, I’m just wasting gas. Just fly the profile, captain Sullivan said. Let us worry about the hitting. Fletcher climbed into his cockpit, likely convinced he was wasting his morning on a farm.

Kid’s delusion. But he agreed to the terms. The Gunners would be firing training rounds, bullets with wax and chalk tips instead of armor piercing lead. They wouldn’t bring the plane down, but they would leave a distinct mark where they hit. Sullivan climbed into the top turret with Sergeant Morrison. The turret was cramped, smelling of hydraulic fluid and stale sweat.

Morrison was shaking. It wasn’t fear of the plane. It was the fear of unlearning. For two years, the army had beaten a rhythm into Morrison’s head. Sea. Target. Track. Target. Lead. Target. Now, Sullivan was asking him to suppress that instinct. It was like asking a driver to close his eyes and hit the gas, because the math said the road was straight. Pick your point.

Sullivan ordered 2000ft out just above that line of trees. Lock your turret. Do not move your hands. The radio crackled. Inbound. Fletcher called. Morrison saw the P-47 tip its nose over at 4000ft. It was a heavy, terrifying machine, plummeting toward them at 400mph.

As the fighter grew larger in the Plexiglas swelling from a speck to a monster, Morrison’s hands twitched his muscles, screamed at him to swing the guns to follow the threat. Hold it, Sullivan whispered. His hand clamping on Morrison’s shoulder. Wait for the trap. The roar of the P-47 engine began to drown out the world. The plane was coming straight down the pipe, 12:00 high. Fire! Sullivan yelled. Morrison didn’t name.

He just squeezed the twin 50 calibers hammered against his chest. Thump thump thump thump. He wasn’t shooting at the plane. He was shooting at the empty air above the tree line. It felt wrong. It felt futile. And then the P-47 flashed through the stream of tracers. It happened in a blink. One moment the sky was empty.

The next, the fighter had passed through the exact point Sullivan had calculated. Fletcher pulled out of the dive with a scream of agonizing metal banking hard to the left. The radio remained silent for a long 10s then Fletcher’s voice came back, sounding different, shaken. Range control. I’m hit. I am hit multiple times.

Morrison slumped in his harness. He hadn’t moved his guns an inch. He had killed a fighter pilot by doing absolutely nothing but trusting the math. Sullivan ran the other five gunners through the same drill. Brennan the machinist. Kowalski, the vengeful friend. One by one, they fought the urge to track.

One by one, they held the fixed point, and one by one they scored hits. When Captain Fletcher finally landed and taxied back to the staging area, he shut down the massive radial engine and climbed out on the wing. He walked around to the front of his aircraft. The P-47 was covered in chalk marks the nose, the left wing root. The fuselage.

Splatters of white wax proved that if this had been a real dogfight, Fletcher would be a burning wreck in a French field. Fletcher looked at Sullivan, then at the chalk. Where did you learn to shoot like that? He asked. Kansas? Sullivan replied. Shooting coyotes well. Fletcher wiped a smear of chalk from his cowling. You better teach this to every gunner in England before the sun goes down.

That was the problem. Sullivan had proven the Kansas variable worked on the ground with six guys. But to change the war, he needed to change the doctrine of the entire Eighth Air Force. And in the military, you don’t just change the rules. You need a general to sign the paper. Sullivan knew that going through the chain of command would take months. He didn’t have months.

The bombers were flying again tomorrow. He needed to go straight to the top. The man holding the lives of the bomber crews in his hands was Brigadier General Frederick Anderson, commander of VIII Bomber Command. Anderson was a rare breed in 1943, a general who was only 37 years old. He wasn’t a desk jockey. He flew combat missions. He knew the smell of fear in a cockpit.

Sullivan drove to Anderson’s headquarters at 1400 hours. He walked up to the outer office. Dusty holding his notebook, still wearing his flight coveralls. The general’s aide, a crisp captain with zero combat time, looked at Sullivan like he was a stain on the carpet. The general is busy, Sergeant. If you have a training suggestion, submit form 42 B to your squadron commander.

Sullivan didn’t move. I don’t have a suggestion, sir. I have a method that just stopped a P-47 head on. And if I don’t tell the general more boys are going to die tomorrow. The aide started to call the MPs, but the heavy oak door behind him opened. Major General Anderson stood there. He had heard the commotion.

He looked at the aide, then at the dusty sergeant with the intense eyes. Anderson had seen the casualty reports from Swinford. He knew they were losing the war of attrition. You have five minutes, Sergeant Anderson said, holding the door open. Don’t waste them. Sullivan walked into the lion’s den. He laid his notebook on the mahogany desk. He didn’t salute. He didn’t apologize.

He opened the book to the page with the geometry of the trap, sir. Sullivan started the manual. Says we have to track the target. The manual is wrong. The Germans are moving too fast. We can’t hit them by chasing them. We have to wait for them. He explained the closing speed. He explained the 2.3 second window. He explained the chalk marks on Captain Fletcher’s plane.

Anderson listened in silence. He was a pilot. He ran the engagement in his head. He realized Sullivan was describing exactly what he had seen in the air tracers trailing behind German fighters because the gunners couldn’t keep up. When Sullivan finished, the room was quiet. The clock on the wall ticked. You tested this? Anderson asked. This morning, sir.

Six gunners all hits the pilot. Captain Fletcher said he’d be dead. Anderson looked at the notebook, then at the sergeant. He saw the desperation of a man who knew he was right but had no power. What do you need? Anderson asked. Two days, Sullivan said. Give me the range. Give me volunteers. Let me train a real strike force.

Anderson closed the notebook and pushed it back across the desk. You have two weeks. The fleet is standing down for repairs until November. If it works, you save the Air Force. If it fails, you’re back to loading bombs. Get out of here and get to work. Sullivan walked out of the office with the power of a general behind him. He had bypassed the colonels, the committees and the rulebook.

Now he had 14 days to turn a farm trick into a weapon of war in the military. Official orders travel through paperwork, but survival tactics travel through whispers. Sullivan had three days, but he didn’t try to train the entire Eighth Air Force himself. He used a force multiplier. He took his six original disciples Morrison, Brennan, Kowalski, and the others and turn them into apostles of the fixed point.

They didn’t just teach the method, they evangelized it. They went into the barracks and the mess halls, grabbing terrified gunners by the shoulders and drawing diagrams on napkins. The green logic of the army hierarchy said this was impossible. You cannot retrain a specialized force in 72 hours, but the purple reality of desperate men is different.

By October 18th, just days after the Schweinfurt Slaughter 30 gunners were certified. By October 20th, that number had jumped to 70. The method didn’t even have an official name yet. The paperwork, called it fixed point fire control, but the men climbing into the turrets called it farm Kid aiming or simply coyote shooting. They didn’t care about the nomenclature. They only cared that for the first time in months, they felt like hunters instead of prey.

The test came four days later. On November 3rd, 1943, the Eighth Air Force launched a deep penetration raid targeting the naval yards at Wilhelmshaven. The flight path took them through the exact same corridor where the Germans had massacred them weeks earlier.

It was a gauntlet of flak and fighters scattered throughout the massive formation where 43 specific B-17 bombers. These weren’t special models. They didn’t have extra armor. What they had were gunners who had spent the last two weeks staring at imaginary spots on a wall. Training their muscles to not move. At 11:03 a.m., the test began. The radio calls were identical to the massacre of the 14th fighters.

12:00 high head on a swarm of Messerschmitt Bf 109 appeared out of the sun, forming up for the headshot. They had done this 100 times. They expected the Americans to spray wild panic fire tracers that would trail harmlessly behind them. They expected to slash through the formation, kill the pilots, and loop back for a beer.

But as the German squadron leader tipped his wing and dove, he didn’t realize the rules of the game had changed. Inside the turret of the lead B-17. The gunner didn’t track the diving fighter. He ignored the screaming instinct to follow the threat. Instead, he locked his turret onto a patch of empty blue sky at zero deflection. 600 yards out, he pressed the triggers.

Thump thump thump. He wasn’t firing at the German. He was building a wall. The German leader hit that wall at 600mph. One moment he was a predator. The next, his engine cowling disintegrated. He flew directly into the stream of 50 caliber rounds that had been waiting for him. It was instantaneous.

3 Bf 109s were ripped apart on the very first pass. They didn’t just take damage. They ceased to be aerodynamic. The second wave of Germans flying Focke-Wulf 190s saw the lead planes disintegrate, but couldn’t process why they committed to their dive. Two more fighters exploded. The radio traffic over Wilhelmshaven wasn’t filled with panic this time.

It was filled with the stunned savage joy of men who were finally hitting back. Got him. He flew right into it. The effect on the Luftwaffe was psychological shock. Fighter pilots are brave, but they aren’t suicidal. They were used to fighting an enemy that missed. Suddenly, the Americans were shooting with impossible precision. After just four minutes of combat, the German formation broke.

They scattered. They had lost seven fighters in 200 and 40s. That level of attrition was unsustainable. The German commander, realizing his tactics were no longer working, ordered his planes to disengage. The trap had sprung. The coyotes ran away. The B-17s dropped their payloads on the naval yards and turned for home.

The flight back to England was tense, but the tally told the story. The formation as a whole suffered losses. War is never perfect. Four B-17s from untrained groups went down. But then the counters looked at the specific group of 43 bombers carrying Sullivan students. Losses. Zero 43 planes went out. 43 planes came back. When the wheels touched down on the tarmac in England, the sun was setting.

Usually the flight line is empty except for the ground crews. But today, a solitary figure was standing by the jeep at the end of the runway. It was Brigadier General Anderson. He hadn’t waited for the report to be typed up. He hadn’t sent an aide. He wanted to see with his own eyes. He watched the 43 coyote bombers taxiing. He saw the gunners climb out. They weren’t haunted ghosts this time. They were alive.

And they knew why. Sergeant Morrison slid out of his hatch. His flight suit was soaked in sweat. His face black with cordite and oil. He spotted Sullivan standing near the general’s jeep. Morrison didn’t salute. He walked straight up to the 19 year old farm kid. Grabbed him by the shoulders and said four words that no metal could ever replace. You saved my life.

Morrison had two confirmed kills that day. More than he had achieved in his previous 11 missions combined. He told Sullivan that the German pilots looked confused before they died. They had flown straight into the trap exactly as the physics predicted. Technical Sergeant Kowalski, the man who had lost his friend, climbed down next. He had downed an Bf 109.

He walked up to Sullivan, lit a cigaret with a shaking hand, and said. Today was different. Today they learn what it feels like to die. General Anderson watched this reunion. He looked at the 43 bombers sitting safely on the hard stand. He realized that a sergeant with a high school education had done what the entire Pentagon Research Division had failed to do.

He turned to Sullivan. How many men have you trained? 73, sir. Trained everyone? Anderson ordered starting tomorrow. Every gunner in the Eighth Air Force learns to shoot coyotes. The experiment was over. The doctrine was dead. The era of the fixed point had begun. The spread of the Kansas method wasn’t just a ripple.

It was a tidal wave that washed away the Luftwaffe as dominance. By December 1st, just six weeks after the experiment. Sullivan had personally trained 800 gunners. Each of those men became a seed, teaching five others in their squadrons. The result was a statistical miracle. In September, before the farm Kid intervened, the Eighth Air Force lost 352 heavy bombers.

By December, with the fixed point method in widespread use, losses plummeted to 189. German fighter kills dropped by 60%. The head on attack, once a guaranteed kill for a German pilot, had become a suicide pact. By 1944, the Luftwaffe had lost 1840 fighters to bomber defensive fire. Double their losses from the previous year. They were no longer the hunters. They were the coyotes.

And the Americans had finally learned how to mend the fence. But in the military, innovation is often claimed by the institution, while the innovator is merely processed. In March 1944, Sullivan was ordered back to the United States. He spent the rest of the war in the dust of Texas and Nevada running gunnery schools.

He trained 3400 more men, embedding the fixed point into the DNA of the Air Force. Yet when the victory parades marched down Fifth Avenue, Sullivan wasn’t on the float. He received no Distinguished Flying Cross. No Legion of Merit. General Anderson, the man who had authorized the experiment, wrote privately that a sergeant from Kansas had saved more lives than any tactical innovation in the theater. But publicly, the credit went to improve training doctrine.

Sullivan didn’t fight for credit. He declined a commission to become an officer. In November 1946, he simply took off the uniform, packed his bag, and went home to Junction City. He went back to the chicken. He went back to the farm. For 42 years he lived a quiet life.

He never bragged at the local bar about changing the course of the air war. He never mentioned the geometry of survival to his own children. To his neighbors, he was just Ray, the guy who was good with a 22 rifle. Raymond Sullivan died on July 8th, 1992. He was 68 years old. His obituary in the local Kansas paper was brief.

It mentioned he was a veteran and a gunnery instructor. It did not mention that he had personally saved an estimated 300 American lives. It did not mention that 37 German planes fell from the sky because of his math. His funeral was small, mostly family and local friends. But as the service ended, three elderly strangers stepped forward. Sullivan’s children didn’t know them. They were former top turret gunners.

They had flown in 1944. They had traveled across the country not to bury a farmer, but to honor a savior. They told the family the truth that history books had ignored. We are here because your father taught us how to stop time. History is often written by the generals, but it is made by the farm kids.

Raymond Sullivan didn’t get the medal, but he got something better. He got to know that somewhere in America, hundreds of men were bouncing grandchildren on their knees. 00:41:15:03 – end Unknown Children who only existed because a 19 year old boy in a control tower decided to ignore the manual and trust the farm.

Rest in peace, Sergeant, and thank you.

News

CH2 . How One Tail Gunner’s “Recklessly Savage” Counter-Attack Obliterated 12 Bf 109s in Just 4 Minutes — And Force a Brutal Rethink of Air Combat Tactics Forever..?

How One Tail Gunner’s “Recklessly Savage” Counter-Attack Obliterated 12 Bf 109s in Just 4 Minutes — And Force a Brutal…

ch2 . The Rifle the Army Tried to Erase — Until One Defiant Farm Boy Used It to Hunt Down Nine Japanese Snipers Before Dawn,…

The Rifle the Army Tried to Erase — Until One Defiant Farm Boy Used It to Hunt Down Nine Japanese…

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

CH2 . America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped as North Korean fighters strafe the runway, destroying transports one by one. Enemy armor is twenty miles away and closing. North Korean radar picks up five unidentified contacts approaching from the sea. The flight leader squints through his La-7 canopy.

America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped…

CH2 . Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above Cape Bon, Tunisia.

Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above…

CH2 . Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles northwest of Lelay, New Guinea. The oil blackened hand trembled as a Japanese naval officer gripped the splintered remains of what had once been part of the destroyer Arashio’s bridge structure. His uniform soaked with fuel oil and seaater, recording in his mind words that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles…

End of content

No more pages to load