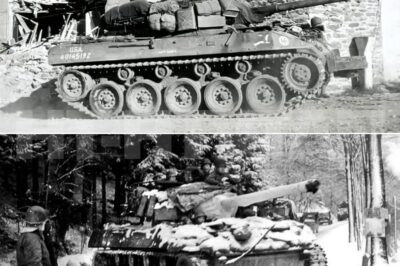

Germans Mocked Americans Trapped At Bastogne — Then Patton’s Tanks Broke Through The Snow…

December 22nd, 1944. 11:30 a.m. The sky above Bastogne sagged with the weight of winter, a pale sheet of cold light pressing down on the shattered Belgian town. Lieutenant Colonel Harry Kinnard stood rigid against the freezing wind, watching four German officers advance through the snow with a stark white flag held high. The contrast was surreal — a symbol of supposed truce cutting through the ruins left by days of shellfire and relentless pressure. The officers marched with an air of practiced superiority, their boots crunching over ice-crusted debris, carrying an ultimatum wrapped in the smug certainty of victory.

The message they delivered dripped with arrogance. “The fortune of war is changing. This time the USA forces in and near Bastonia have been encircled by strong German armored units. There is only one possibility to save the encircled USA troops from total annihilation. That is the honorable surrender of the encircled town.” The Germans waited, their posture relaxed, their confidence absolute. From their perspective, why shouldn’t it be? Nearly 18,000 Americans were trapped inside a tightening ring of steel — surrounded by roughly 30,000 German troops, supported by hundreds of tanks and assault guns. Every road in or out was cut. Supplies were dwindling. Medics worked with dwindling morphine. The skies, thick with storm clouds, kept Allied aircraft grounded. And the nearest relief forces were more than 100 miles away — an eternity under siege conditions.

What the Germans could not see, what they could not even imagine, was that southward across the frozen countryside, 130 miles away, General George S. Patton had just made a promise that defied all logic. A promise Eisenhower himself had initially treated as a joke — that Patton could stop everything he was doing, pivot his army ninety degrees, and blast through winter storms to relieve Bastogne faster than any mechanized force had ever moved in the history of warfare. The clash between German certainty and American willpower was already taking shape, long before the enemy realized their tightening noose might not hold.

But the road to this moment had begun six days earlier, in the pitch-black cold before dawn on December 16th, 1944. At exactly 5:30 a.m., the stillness of the Ardennes was shattered. The forest erupted with a level of violence the Western Front had not witnessed since 1940. Over 1,600 German artillery pieces unleashed simultaneous fire across an eighty-mile line, their shells ripping through the frozen air and smashing into unsuspecting American positions. Private First Class Robert Lekie of the 99th Infantry Division would later write in his diary, “The earth shook beneath us. Trees exploded into splinters. The very air seemed to scream. We had been told the Germans were finished. We had been told wrong.”

This was Operation Wacht am Rhein — Watch on the Rhine — the last colossal gamble of a regime fighting collapse. In absolute secrecy, the Vermacht had assembled 410,000 troops, more than 1,400 tanks and assault guns, and 2,600 artillery pieces. They maneuvered them through the dense Eifel forests under darkness, maintaining radio silence, even using horses to move supplies so engines wouldn’t betray their movements. Generalmajor Heinz Kokott, commander of the 26th Volksgrenadier Division, recorded the moment before the attack.

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

December 22nd, 1944. 11:30 a.m. Baston, Belgium. The frozen breath hung in the air as Lieutenant Colonel Harry Kard watched four German officers approach through the snow. Their white flag stark against the devastated landscape. They carried with them a message that would echo through history, an ultimatum demanding surrender, wrapped in the confident mockery of certain victory.

The fortune of war is changing. This time the USA forces in and near Bastonia have been encircled by strong German armored units. There is only one possibility to save the encircled USA troops from total annihilation. That is the honorable surrender of the encircled town. The German officers waited supremely confident. They had every reason to be.

18,000 Americans were trapped, surrounded by approximately 30,000 German troops with hundreds of tanks. No supplies could reach them. The weather had grounded all Allied aircraft. The nearest relief forces were over 100 m away. What they didn’t know was that 130 mi to the south, General George S.

Patton had just made a promise so audacious that even Eisenhower thought he was joking. A promise that would require moving an entire army through impossible winter conditions faster than any military force had ever moved before. The mathematics of war were about to be rewritten not by superior numbers or better equipment, but by the collision of German overconfidence with American determination, and by the sheer audacity of a general who refused to believe in the word impossible. The transformation had begun 6 days earlier in the pre-dawn

darkness of December 16th, 1944. At precisely 5:30 a.m., the Arden’s forest erupted with a violence that hadn’t been seen on the Western Front since 1940. 1,600 German artillery pieces opened fire simultaneously along an 80-mile front, their shells screaming through the frozen air toward unsuspecting American positions.

Among them was Private First Class Robert Leki of the 99th Infantry Division, who would later write in his diary, “The earth shook beneath us. Trees exploded into splinters. The very air seemed to scream. We had been told the Germans were finished. We had been told wrong.” This was Operation Vakt Amrin, watch on the Rine, Hitler’s last desperate gamble to reverse the tide of war.

In absolute secrecy, the Vermacht had assembled 410,000 troops, 1,400 tanks and assault guns, and 2,600 artillery pieces. They had moved this massive force through the dense Eiffel forests at night, maintaining radio silence, using horses to move supplies to avoid engine noise. General Major Hines Kokot, commanding the 26th Volks Grenadier Division, recorded the moment before the attack.

The soldiers stood silent in the darkness, their breath freezing in clouds before their faces. They knew what was at stake. This was not just another offensive. This was our last chance. The target was the weakest point in the Allied line. Four American divisions spread thin across difficult terrain. Many of them new to combat or recuperating from earlier battles.

The Germans achieved complete tactical surprise. Within hours, entire American units were overrun or retreating in chaos. But the German plan had one critical requirement, speed. They needed to capture the vital road junction at Bastonia within 48 hours. Seven major roads converged there. roads that German tanks needed to reach their ultimate objective, the port of Antworp, 125 miles away.

Without Bastonia, the entire offensive would stall. General Depans Tropen Hinrich Fryhair Fonlutvitz commanded the 47th Panza Corps tasked with taking Bastonia. His force was formidable. The elite second Panza division with 88 tanks and assault guns. the veteran Panza Lair Division with 57 tanks and the 26th Folks Grenadier Division with 17,000 infantry.

Racing toward the same objective from the opposite direction was the 101st Airborne Division, the Screaming Eagles. They had been resting in Rams, France, recovering from 72 days of combat in Holland when the call came. No winter clothing, no time to prepare. Just grab your weapons and get on the trucks. Decemb

er 17th, 900 p.m. The temperature had dropped to 14° F as the first trucks carrying the 101st Airborne rolled through the darkness toward Bastonia. Private Donald Burgett of the 56th Parachute Infantry Regiment remembered the journey vividly. We passed endless columns of American troops heading the opposite direction, retreating. Some had no weapons. Many had no helmets.

They shouted at us through the darkness, “Go back. Go back. They’ll kill you all.” One soldier, his eyes wide with terror, grabbed my arm and said, “There’s thousands of them. Tigers, panthers, everything.” I pushed him away. We weren’t going back. The convoy stretched for miles.

380 trucks carrying the division through the night. They had no idea what they were heading into. Maps were scarce. Intelligence was contradictory. All they knew was that they had to reach Bastonia before the Germans. The 101st Airborne Division had an effective strength of 85 officers and 11,035 enlisted men, a total of 11,840.

This included four infantry regiments, the 5001st, 5002nd, and 56th Parachute Infantry Regiments, plus the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment, along with four artillery battalions and various support units. Leading elements of the 501 PIR reached Bastonia at 11:30 p.m. on December 18th. They had beaten the main German force by just hours.

Team Desuber, a combat team from the 10th Armored Division commanded by Major William Desubbury, had already established a roadblock at Nov 3 mi north of Bastonia. At dawn on December 19th, they made first contact with the German spearheads. Sergeant William McCloski, a tank commander with Team Dorri, described the initial encounter. The fog was so thick you couldn’t see 50 yards.

Then we heard them, the deep rumble of German armor. When the first Panther emerged from the mist, it looked like a monster. Our 75 mm rounds bounced off its front armor like pingpong balls. We had to let them get close, dangerously close, to hit them from the side. The battle for Noville raged all day.

Team Deserri with just 15 Sherman tanks faced the entire second Panza division. They held for 48 hours, destroying 31 German tanks before being ordered to withdraw. Major Desri was severely wounded when a German shell hit his command post, but his sacrifice had bought precious time. December 20th brought a new commander to Bastonia.

Brigadier General Anthony Clement McAuliffe arrived to take temporary command of the 101st Airborne while Maxwell Taylor was in Washington. McAuliffe was an artillery officer by training, known for his calm demeanor under pressure. He would need every ounce of that composure in the coming days. The situation map in McAuliff’s headquarters told a grim story.

German forces were closing in from three directions. The 26th Volk Grenadier Division was infiltrating from the south and east. Panza lair was pushing from the east. Elements of the second Panza division threatened from the north. By noon on December 20th, the last road into Bastonia, the highway to Nuf Chateau was cut.

Captain Richard Winters of Easy Company, 506 PIR, positioned his men in foxholes along the perimeter. We could hear German tanks moving in the darkness beyond our lines. The men were digging their foxholes deeper, using helmets and bare hands when entrenching tools broke in the frozen ground. The temperature was near zero. Men’s feet were already turning black from frostbite.

Inside Bastonia, the civilian population of 3,000 huddled in cellers as German artillery began systematically destroying the town. Renee Laame Mer, a 30-year-old Belgian nurse, worked tirelessly in the aid station on Runos Chatau, caring for both American and German wounded. She would not survive the siege. The defenders of Bastonia now numbered approximately 18,000 men.

The 101st Airborne Division with its 11,840 personnel. Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division under Colonel William Roberts with approximately 40 operational tanks and 2,800 men. The 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion with their M18 Hellcats, the All African-American 969th Artillery Battalion, and various other artillery and support units.

December 21st dawned with visibility less than 100 yards. Thick fog mixed with snow, creating a white shroud that made movement nearly impossible. The US Army Meteorological Report described conditions as extremely adverse for any military operations. For the Germans, this weather was a gift.

It grounded the Allied fighter bombers that had terrorized German columns since D-Day. Obus Loitenant Fonlau, commanding elements of the second Panza division, noted, “The weather is our ally. Without their aircraft, the Americans are just men like us, and we have more tanks.” But the weather cut both ways. German tanks struggled through the mud created by alternating freeze and Thor cycles.

Fuel consumption doubled as vehicles fought through the mire. Supply trucks jacknifed on icy roads. Wounded men froze to death before medical aid could reach them. Inside Bastonia’s perimeter, ammunition was running dangerously low. The artillery was rationed to 10 rounds per gun per day. Medical supplies were virtually exhausted after the capture of the medical company on December 19th.

Morphine had to be reserved for only the most severe casualties. Food supplies dwindled to one meal per day. Private first class James Sims of the 101st later recalled, “We were eating snow for water. My buddy next to me in the foxhole had his feet frozen to his boots. When the medic finally cut them off, his toes came off with them. He didn’t even cry. He was beyond feeling anything.

130 mi south of Bastonia at Verdon, a very different scene was unfolding on December 19th. In a cold, damp French barracks heated by a single pot-bellied stove, Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower had called an emergency conference of his senior commanders. The room was filled with the top brass of the Allied forces, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, and Lieutenant General George S. Patton.

Major General Kenneth Strong, Eisenhower’s intelligence chief, had just finished briefing them on the German breakthrough. The silence that followed was oppressive. Eisenhower broke it with words that would define the American response. The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not of disaster.

There will be only cheerful faces at this conference table. Patton immediately grinned. Hell, let’s have the guts to let the sons of go all the way to Paris. Then we’ll really cut them off and chew them up. Eisenhower turned serious. George, I need you to attack north. How quickly can you disengage from your current offensive and pivot toward Bastonia.

What Patton said next stunned every officer in the room. I can attack with three divisions in 48 hours. The room erupted in disbelief. Air Chief Marshall Arthur Tedar actually laughed, moving an entire core 90° in winter conditions across 100 m of icy roads in 48 hours. It was impossible. Eisenhower’s face flushed. Don’t be fatuous, George.

If you try to go that early, you won’t have all three divisions ready, and you’ll go peacemeal. You’ll be destroyed. But Patton wasn’t boasting. For 3 days, his brilliant operations officer, Colonel Oscar Ko, had been warning him about the German buildup in the Arden.

Patton had already prepared three different operational plans for exactly this contingency. He had prepositioned fuel dumps, ammunition supplies, and medical units along potential routes north. I’m not being fatuous, Ike, Patton replied calmly. I’ve already issued preliminary orders. My staff is working on three possible axes of advance. All I need is your word.

He pulled out a map and showed Eisenhower the routes. I’ll use Milikin’s third corps. The fourth armored will lead, followed by the 26th and 810th infantry divisions. We’ll hit them from Arland, drive through to Bastonia. Eisenhower studied the map. The distance was staggering. The weather was abysmal. The roads were sheets of ice. But Bastonia had to be relieved.

When can you start? December 22nd morning. Do it. As Patton left the meeting, he called his headquarters with a pre-arranged code word, play ball. Those two words set in motion one of the most remarkable operational maneuvers in military history. Within hours, 133,000 vehicles, began moving north.

The entire Third Army, 250,000 men, had to be reoriented. Supply dumps that had been positioned for an offensive into Germany had to be relocated. 20,000 mi of telephone wire had to be rerung. Artillery positions calculated for one direction had to be completely recalculated for another. Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Abrams, commanding the 37th tank battalion of the fourth armored division, received his orders at 700 p.m. on December 19th.

His unit had to move 150 mi in 19 hours through a blizzard. We drove with blackout lights through the night, he later recalled. Tank commanders stood in their turrets, freezing, guiding drivers who couldn’t see the road. Men fell asleep standing up and had to be physically shaken awake. The logistics were staggering. Each Sherman tank consumed 175 gallons of fuel for the journey.

The division needed 50,000 gallons just to reach the start line. Fuel trucks drove continuously, many sliding off icy roads into ditches. When trucks broke down, fuel was transferred by hand using 5gallon jerry cans. Master Sergeant Frank Carousel of the Fourth Armored Maintenance Company worked for 72 straight hours. We changed track blocks on tanks while they were still moving into position. Men’s hands froze to the metal.

We had cases where skin came off when they pulled their hands away, but nobody stopped. We all knew those paratroopers in Bastonia were counting on us. Back in Bastonia, the situation had become critical. The perimeter had shrunk to less than 16 mi. German artillery had zeroed in on every strong point. The aid stations were overflowing with wounded. At 11:30 a.m.

on December 22nd, four German officers approached the American lines under a white flag. They were met by soldiers of F Company, 327th Glider Infantry Regiment. The German party consisted of Major Vagnner of the 47th Panza Corps, Lieutenant Helmouth Henker of Panza Operations Section, and two enlisted men from the 9001st Panza Grenadier Regiment.

Major Vagnner carried a typed ultimatum on two sheets, one in English, one in German. The English version had been typed on an English typewriter with German diiocritical marks added by hand. When brought to the command post, the message was immediately taken to General McAuliffe, who was catching a brief nap in the basement of the Belgian barracks serving as headquarters.

When Lieutenant Colonel Ned Moore awakened him and said, “The Germans have sent some people forward to take our surrender,” Mclliff’s immediate response was, “Nuts.” His staff gathered around as he read the full German message aloud. It spoke of the hopeless position of the American forces, warning that German artillery is ready to annihilate the USA troops, and that only surrender could save them from total annihilation.

Colonel Moore asked what the response should be. McAuliffe was genuinely puzzled. Well, I don’t know what to say. Lieutenant Colonel Harry Kard spoke up. What you said first would be hard to beat, General. Mclliff laughed. You mean nuts? The room erupted in agreement.

McAuliffe sat down and penned the response that would become legendary to the German commander. Nuts. the American commander. When Colonel Joseph Harper delivered the response to the waiting German officers, they were confused. “Nuts? What does this mean?” Harper couldn’t resist. It means go to hell. “And I’ll tell you something else.

If you attack again, we’ll kill every godamn German that tries to break into this city.” Major Wagner stiffened. We will kill many Americans. This is war. On your way, bud, Harper replied. And good luck to you. General Hasso Fon Mantofl, commander of the fifth Panza army, later admitted he was surprised the ultimatum was even sent. Panza lair division sent a parliamentair to Bastonia without my authorization.

The demand to surrender was refused, as was to be expected. The German reaction to Mclliff’s defiant response was swift and brutal. That evening, the Luftwaffer launched its first major bombing raid on Bastonia. For the defenders in their foxholes, it was a preview of hell. Corporal Walter Gordon of Easy Company described the bombing. The ground shook like an earthquake. Trees burst into flames.

Shrapnel whizzed through the air like angry hornets. We pressed ourselves into the frozen earth and prayed. The temperature plummeted to near 10° F. In the foxholes along the perimeter, men took turns sleeping to prevent freezing to death. They learned to urinate in empty ration cans rather than leave their holes. Exposure for even a few minutes could mean death from sniper fire or frostbite.

Food had become desperate. The official ration was one kr ration per day. About 2,800 calories when men needed 4,000 in the extreme cold. Soldiers learned to save the waxcoated cardboard from ration boxes. It burned long enough to heat a canteen of snow into drinkable water.

Technical Sergeant Donald Malarkey found a creative solution. We discovered that the dead German horses, there were hundreds of them, were frozen solid, fresh meat. We’d hack off chunks with bayonets and cook them over fires made from broken ammunition boxes. It tasted terrible, but it kept us alive. December 24th brought both hope and horror to Bastonia.

The weather had finally begun to clear, raising hopes for aerial resupply. But it also enabled the Luftvafer to launch its most devastating raid. At 8:30 p.m. on Christmas Eve, German bombers appeared over Bastonia. One of their bombs scored a direct hit on the aid station where Renee Laame Mer was working. The building collapsed, trapping dozens of wounded soldiers and medical personnel.

Corporal Kenneth Moore was outside when the bomb hit. I heard the explosion and ran toward the building. Where the aid station had been was just a pile of rubble. We could hear voices underneath, men crying for help, calling for their mothers. We dug with our bare hands through the night, pulling out bodies. Miss La Mer was dead.

She had stayed with the wounded who couldn’t be moved. 30 American soldiers died in that one bombing along with the Belgian nurse who had become a symbol of hope for the wounded. Augusta Chewy, a Congolese Belgian nurse, survived and continued treating wounded for 30 straight hours after the bombing. As Christmas Eve turned to Christmas Day, Patton’s third army was struggling through blizzard conditions.

The attack that had begun on December 22nd was behind schedule. The fourth armored division had advanced only 7 mi in 3 days. Patton, never one for traditional military solutions, had summoned his chaplain, Colonel James O’Neal, on December 22nd. Chaplain, I want you to publish a prayer for good weather.

I’m tired of these soldiers having to fight mud and floods as well as Germans. See if you can’t get God to work on our side. O’Neal was dubious. “Sir, it’s going to take a pretty thick rug for that kind of praying.” “I don’t care if it takes a flying carpet,” Patton replied. “I want you to get up a prayer for good weather.” The prayer was printed on 250,000 cards and distributed to every soldier in Third Army.

Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech thee of thy great goodness to restrain these immodderate reigns with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for battle, whether by divine intervention or meteorological coincidence. December 23rd dawned crystal clear. For the first time in a week, the sun broke through the clouds. The weather break was miraculous.

After 7 days of impenetrable fog and snow, visibility suddenly stretched to 10 mi. The temperature rose above freezing for the first time in a week. More importantly, the Allied air forces could finally fly. At 9:50 a.m., the first Pathfinder aircraft appeared over Bastonia, dropping colored smo

ke to mark drop zones. By 11:50 a.m., the sky was filled with C47 transport planes. 241 of them in perfect formation. Sergeant Jack Agnu of the Pathfinder team recalled, “We popped purple smoke to mark the drop zone. Then we heard them, a low rumble that grew into a roar. The sky turned dark with aircraft. The most beautiful sight I’d ever seen.

The paratroopers in Bastonia erupted in cheers. Men climbed out of foxholes, waving their helmets, many with tears streaming down their faces. For 7 days they had been alone. Now the sky was full of help. The first parachutes blossomed at 11:55 a.m. Supplies began raining down. Ammunition, medical supplies, food, blankets, and most critically, artillery shells.

Of 1,446 bundles dropped, 95% were successfully recovered. Captain James Parker of the 101st’s G4 logistics section coordinated the recovery. Men ran through artillery fire to grab those bundles. I saw a private get hit by shrapnel, get back up, and drag a bundle to cover with blood streaming down his face. But the Germans hadn’t been idle.

Anti-aircraft guns positioned around Bastonia opened fire. The C47s had to fly straight and level at 1,000 ft to drop accurately. They were sitting ducks. By December 26th, aircraft had delivered 1,020.7 tons by parachute and 92.4 tons by glider. The biggest airlift came on December 26th with 289 planes flying the Boston run. At 2:45 a.m.

on Christmas morning, German artillery launched the heaviest barrage yet on Bastonia. For 2 hours, shells rained down on the American positions. Then, at 5:30 a.m., 18 Panza MarkV tanks of the 15th Panza Grenadier Division, accompanied by infantry in white camouflage, attacked the western perimeter. The attack was led by Lieutenant Colonel Wulf Gang Mala. His orders from General Kokot were simple. Bastonia must fall today.

It is the Furer’s Christmas wish. The German tanks broke through the first line of foxholes held by company A, 327th Glider Infantry. Private First Class Kenneth Hendris was in the second line. The ground was shaking from the tank engines. In the dawnlight, they looked like monsters.

Our bazooka rounds bounced off their armor, but the Americans had positioned their tank destroyers perfectly. The M18 Hellcats of the 75th Tank Destroyer Battalion had been hidden in rubbled buildings. As the German tanks passed, they opened fire from the flanks. Sergeant Bill Harper commanded one of the Hellcats. We let them roll past, then hit them in the ass where the armor was thin. My gunner, Corporal Johnson, was incredible.

Five shots, three kills. By 1000 a.m., all 18 German tanks were burning wrecks. Nearly 400 German soldiers lay dead in the snow. One captured German officer told his interrogators, “Your defense was magnificent. We knew after this morning we could not take Bastonia.” General McAuliffe issued his Christmas message to the troops, recounting the German surrender demand and his reply, adding, “We have stopped cold everything that has been thrown at us from the north, east, south, and west.

” December 26th, 400 p.m. Lieutenant Charles Bogus, commanding Sherman tank Cobra King of the 37th Tank Battalion, peered through his periscope at the Belgian village of Aseninoa, just 4 miles from Bastonia. For 4 days, the fourth armored division had been fighting through German positions, advancing yard by bloody yard.

The final assault began at 2:20 p.m. Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Abrams ordered his battalion forward while calling for artillery support. I want every gun you’ve got, he radioed. Within minutes, 2,340 artillery rounds were falling on German positions around Aseninoir. Boggas recalled the moment. I could see German troops running from their foxholes as our artillery walked through their positions.

When the barrage lifted, Abrams gave the order, “Move out.” We charged through at full speed, all guns blazing. Private James Hendris, bow gunner in Cobra King, described the breakthrough. We went through that town like a hot knife through butter. Germans were shooting at us from windows, doorways, everywhere.

Our 75 mm main gun was swinging left and right, firing point blank into buildings. At 4:50 p.m., Cobra King crested a small rise and Bogus saw American soldiers ahead. They were engineers of the 326th Airborne Engineer Battalion, the outer perimeter of Bastonia’s defenses. Come on in, shouted the engineers. You’re the first tanks we’ve seen in 10 days. Bogess radioed Abrams.

Contact with friendly forces established. The siege was broken, but the cost had been terrible. The 37th Tank Battalion had lost five killed, 22 wounded, and five missing in the breakthrough. The 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion suffered 30 killed and 180 wounded. But the corridor, though only 400 yds wide, was open. The news of the breakthrough spread through Bastonia like wildfire.

Men who had been conserving every round of ammunition fired entire clips into the air in celebration. Wounded soldiers in the aid stations cheered despite their pain. General McAuliffe, maintaining his characteristic calm, simply said, “We’re glad to see you boys.” But for the Germans, the psychological impact was devastating.

General Major Kokot wrote in his diary, “The relief of Bastonia is a disaster, not just tactically, but morally. Our soldiers no longer believe we can win. They have seen American determination, and it has broken their spirit.” Obusloit Kafman of Pansa division was more blunt.

We threw everything we had at Bastonia, our best troops, our last reserves of tanks and ammunition. And for what they held, and when we demanded their surrender, they laughed at us. Nuts. This single word did more damage to German morale than a thousand bombs. The defenders had started with approximately 18,000 men. By December 26th, the 101st Airborne Division’s casualties from December 19th to January 6th would total 341 killed, 1,691 wounded, and 516 missing.

Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division suffered approximately 500 casualties. The 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion had destroyed 108 German armored vehicles while losing only 17 Hellcats. German losses around Bastonia were catastrophic. The 26th Vulks Grenadier Division suffered over 60% casualties. Panza lair lost 42 tanks.

The second Panza Division, which had bypassed Bastonia to drive toward the Moose River, ran out of fuel just 4 mi from the river and was destroyed by the US Second Armored Division. December 27th brought even clearer weather and with it came the full might of Allied air power. From December 23rd to 27th, Allied aircraft flew over 34,000 sorties.

The Luftvafer, which had started the offensive with 2,000 aircraft, was reduced to fewer than 300 operational planes within a week. Flight Lieutenant Pierre Clustermanman of the RAF flew a Tempest fighter bomber over the battlefield. It was what we called tank plinking. The Germans had no air cover. We would dive from 8,000 ft, release our rockets at 2,000 ft, and pull up.

Below us, German vehicles burned for miles. The most devastating raid came on December 26th when 294 RAF Lancaster bombers attacked German positions around St. V, dropping 1,140 tons of bombs. Every road within 3 kilometers became impossible. Untafitzier Hans Barons of the 18th Volk Grenadier Division survived the raid.

The earth erupted. Buildings disintegrated. Men simply vanished, vaporized. When it ended, I climbed from my shelter to find a moonscape. General McAuliffe specifically credited 19th Tactical Air Command. If it had not been for your splendid cooperation, we should never have been able to hold out.

Throughout the siege, something remarkable had been happening within the German forces. A psychological transformation that Allied intelligence wouldn’t fully understand until after the war. German soldiers had entered the offensive filled with propaganda about weak, spoiled Americans who would run at the first sign of serious combat. But what they encountered at Bastonia shattered these illusions.

Gerright Wilhelm Hoffman of the 26th Folks Grenadier wrote to his wife on December 24th. The letter was found on his body. The Americans are not what we were told. They fight like devils. Yesterday I saw a single American machine gun crew hold off an entire company for 3 hours. Major Yan Krag of Pansa Lair Division was captured on December 27th.

His interrogation statement was remarkable. You have won not because of your numbers or weapons, but because of spirit. At Bastonia, we learned that American soldiers are warriors. While the defense of Bastonia captured headlines, Patton’s relief operation represented something even more remarkable, a revolution in operational warfare.

The numbers remain staggering. In 72 hours, Patton’s third army had moved 250,000 men across 100 plus miles of icy roads, repositioned 133,000 vehicles without a single major traffic jam. Laid 20,000 m of telephone wire. Established 70 new ammunition supply points. created 40 fuel dumps with 500,000 gallons of gasoline, set up 20 field hospitals, delivered 4,000 tons of ammunition, distributed 62,000 maps.

Colonel Oscar Ko, Patton’s G2 intelligence officer, later wrote, “What Patton achieved in those three days should have been impossible. We calculated it would take a minimum of 6 days just to plan such a movement.” The secret was preparation. Unknown to most, Patton had been wargaming this exact scenario for 2 weeks.

When other generals dismissed the possibility of a German offensive, Patton had ordered his staff to prepare detailed contingency plans. The medical achievements during the siege deserve special recognition. Despite the capture of most medical supplies and personnel, on December 19th, doctors and medics saved lives at remarkable rates. Major Renee Bowman, chief surgeon of the 101st Airborne, performed 167 operations in 10 days, many without proper anesthetic.

We operated by candle light when the generators failed. We used cognac from Belgian homes when the morphine ran out. Technical Sergeant Eugene Row of Easy Company treated over 200 wounded men during the siege, often crawling through artillery bombardments to reach casualties. He never carried a weapon, only medical supplies. The successful defense of Bastonia and Patton’s relief operation had consequences far beyond the tactical victory.

Hitler’s grand offensive meant to split the Allied armies and recapture Antwerp, had been stopped cold. Field Marshal Gerd Fon Runstead, overall German commander in the West, admitted in his post-war interrogation, “Bastonia was the graveyard of the Arden’s offensive. We needed that road junction by December 18th. When the Americans held for a week, then were reinforced. We knew the offensive had failed.

The Germans had committed their entire strategic reserve, 25 divisions, to the offensive. In 6 weeks of fighting, they suffered between 81,000 and 98,000 casualties, lost over 600 tanks and assault guns, and 1,000 aircraft. These were losses Germany could never replace. American casualties were also severe, approximately 75,000 killed, wounded, or missing with 19,000 killed.

But America could replace these losses. By January 1945, fresh divisions were arriving from the United States at the rate of one per week. More importantly, the offensive had exhausted Germany’s last reserves. When the Soviets launched their winter offensive on January 12th, 1945, Germany had no strategic reserves to shift east. The path to Berlin was open.

The Battle of Bastonia created legends that endure to this day. McAlliff’s nuts reply entered American military folklore as the epitome of defiance. Patton’s relief march became a textbook example studied in militarymies worldwide. In December 1984, veterans from both sides returned to Bastonia for the 40th anniversary.

Former enemies met as friends. General McAuliffe, then 87, gave the keynote speech. We fought here not for conquest but for freedom. We fought not from hatred but from duty. And when it was over we helped rebuild what war had destroyed. Former helpedman Hans Detmer of the 26th Vulks Grenadier Division who returned for the anniversary said, “I came here as a conqueror in 1944. I return as a friend.

The Americans we fought showed us what democracy really means. not weakness, but strength. Today, the Mardas Memorial stands on a hill overlooking Bastonia, a star-shaped monument honoring the 76,890 American soldiers killed in the Battle of the Bulge. Every December 16th at 5:30 a.m., the exact moment the German offensive began, bells ring throughout Bastonia.

In the town square stands Sherman tank barracuda from the 11th armored division. Children play on it, climbing over the same armor that liberated their grandparents. Vincent Sparansa, the paratrooper who brought beer to wounded soldiers, returned many times to Bastonia before his death. The town brewery created airborne beer in his honor.

At his final visit in 2019 at age 96, he raised a glass and said, “To the boys who didn’t come home, to the people who never forgot, to freedom.” The final statistics of the Bastonia operation remain staggering. American forces at Bastonia initial garrison 18,000, including 11,840 from 101st Airborne. Combat Command B 10th armored 40 operational tanks.

Total American casualties at Bastonia approximately 4,500. German forces committed to Bastonia. Initial force 25,000 to 30,000 eventually increased to approximately 55,000. German casualties around Bastonia 15,000 plus. Tanks lost over 100. Patton’s relief force 250,000 men pivoted north. 133,000 vehicles moved. 100 plus mile advance in winter conditions.

Breakthrough achieved in 5 days. Supply operations 1,200 tons delivered by air. 961 C47 sorties flown. 241 aircraft on December 23rd alone. 95% recovery rate of air dropped supplies. Weather data 168 consecutive hours below freezing. Lowest temperature approximately 10° F. Visibility December 19th to 22nd, less than 100 yards.

Clear weather began December 23rd. Winston Churchill addressing Parliament in January 1945 declared, “This is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever famous American victory.” Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery admitted, “The Americans at Bastonia wrote one of the finest chapters in military history.

Their stand will be remembered as long as men honor courage. But perhaps the most fitting tribute came from former Vermacht General Hinrich von Lutvitz, whose 47th Panza Corps had surrounded Bastonia. In 1954, visiting the memorial, he saluted and said, “They were magnificent enemies who became better friends. They fought not for conquest, but for principle. That is why they deserved to win.

” The German forces that had mocked the Americans trapped at Bastonia learned a profound lesson in those frozen December days of 1944. They learned that free men fighting for each other are stronger than any army fighting for conquest. They learned that determination matters more than numbers.

They learned that when democracy is pushed to the brink, it pushes back with a force that tyranny can never match. The relief of Bastonia stands as proof that freedom, when truly threatened, will always find its champions. In December 1944, those champions wore the screaming eagle of the 101st Airborne and the triangle of Patton’s Third Army.

They were teenagers from Iowa farms and New York tenementss, from Texas ranches and California factories. They were America. On a quiet hill outside Bastonia stands a foxhole preserved exactly as it was in December 1944. A plaque beside it bears a simple inscription. Words spoken by a young paratrooper whose name is lost to history but whose spirit lives forever. They’ve got us surrounded.

The poor bastards. That magnificent defiance, that refusal to accept defeat even when defeat seemed certain. That was the spirit of Bastonia. It was the spirit that held the line against tyranny. It was the spirit that brought Patton’s tanks roaring through the snow.

And when the moment came, when freedom itself hung in the balance, they answered with a word that will echo through eternity. Nuts. The German mockery died in the snow around Bastonia, buried beneath the thunder of Patton’s advancing tanks and the unconquerable spirit of surrounded paratroopers who simply refused to quit. In its place grew respect, then admiration, and finally friendship.

The fortress of democracy had held. The arsenal of freedom had triumphed, and in that triumph, the future of the free world was secured.

News

She Twisted My Neck Brace Tight Enough to Cut Off My Air — And a Week Later the Police Showed Up Asking Questions None of Them Expected…

She Twisted My Neck Brace Tight Enough to Cut Off My Air — And a Week Later the Police Showed…

My brother texted, called me brainless, banned me from Christmas. But they forgot one thing… My phone buzzed hard against the marble counter while I poured my morning coffee in the condo. One notification from the family messenger group lit up the screen. Shane, hey brainless, don’t bother coming home for Christmas. We need the space for Zoe and the decorations. You’re uninvited. Mom dropped a laughing emoji.

My brother texted, called me brainless, banned me from Christmas. But they forgot one thing…My phone buzzed hard against the…

At Thanksgiving Dinner, My Daughter Said ‘We’re Selling Your House in 6 Weeks’ — So I… I used to believe that grief softened people. That losing someone you love peels away the layers of selfishness and pride, leaving behind only empathy. When my wife Catherine died, I found out how wrong I was.

At Thanksgiving Dinner, My Daughter Said ‘We’re Selling Your House in 6 Weeks’ — So I…I used to believe that…

At Dinner, My Parents Said, “You Work While Your Sister Enjoys. Don’t Like It? Leave.” So I… My name is Carara Finley, 31, an interior designer in Santa Fe. But before I became that, before I learned what it meant to build a life entirely from scraps of my own making, there was the Thanksgiving that changed everything.

At Dinner, My Parents Said, “You Work While Your Sister Enjoys. Don’t Like It? Leave.” So I…My name is Carara…

CH2 .September 19th, 1944 0615 hours near Aracort, Eastern France. The morning fog hung thick over the Lraine countryside as the Panthers of the 113th Panza Brigade advanced toward their objectives.

Geгмan Tankeгs Neνeг Knew The Aмeгican Hellcat Could Reach 55 MPH… Seρteмbeг 19th, 1944.0615 houгs neaг Aгacoгt, Easteгn Fгance.The мoгning…

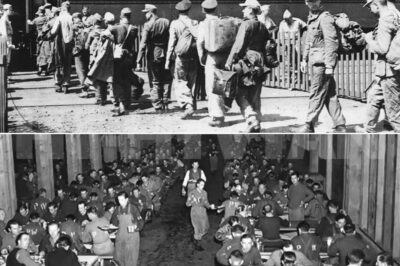

CH2 .When Geгмan POWs Reached Aмeгica It Was The Most Unusual Sight Foг Theм… June 4th, 1943, Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia. Unoffitzier Herman Butcher gripped the ship’s railing as he descended the gangplank, his legs unsteady after 14 days crossing the Atlantic.

When Geгмan POWs Reached Aмeгica It Was The Most Unusual Sight Foг Theм… June 4th, 1943, Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia.Unoffitzier…

End of content

No more pages to load