Germans Laughed at Black Troops — Until the 92nd Infantry Br0ke the Gothic Line…

December 26th, 1944. Monte Belvedere, Northern Apennines, Italy. The winter fog rose from the valleys like breath from a wounded giant, thick and unforgiving, swallowing forests, stone paths, and the jagged silhouette of the Gothic Line itself. Inside one of the concrete command bunkers perched along the mountain ridge, Oberst Hinrich von Schellenburg brought his field glasses slowly to his eyes, studying the dark shapes that moved through the white veil below. He already believed he knew what he was seeing, because his briefing officer had spoken earlier with the casual cruelty of someone who believed prejudice to be fact. Negroes, the officer had said, dismissing them with the confidence of doctrine. The Americans have sent us their weakest troops. Former railroad porters playing soldier.

Schellenburg, a survivor of Stalingrad, a man who had witnessed the Red Army at its most relentless and the Wehrmacht at its most desperate, allowed himself a faint, cold smile. Even after Stalingrad had crushed any illusion about German superiority, old ideologies clung stubbornly to the minds of officers who needed to believe in them. And now, through the drifting fog, he saw the approaching figures—soldiers of the 370th Infantry Regiment, part of the United States Army’s segregated 92nd Infantry Division. An all-Black unit, sent into some of the most punishing terrain of the Italian campaign, asked to accomplish what more experienced divisions had failed to achieve: to assault, climb, and break the most fortified German defensive barrier in Italy, the Gothic Line.

German propaganda had spent years spreading the message that African American troops were weak, unintelligent, undisciplined, and unable to endure the psychological strain of sustained fighting. It was a comfortable belief, and a dangerous one. Nazi ideology insisted that men of African descent lacked the capacity for long-term combat effectiveness, that they would melt away under artillery fire, that they would retreat in panic once met with firm resistance. For many German soldiers, this wasn’t merely something they heard; it was something they accepted as scientific truth.

But Schellenburg could not see the invisible burdens those American soldiers carried—the years of fighting their own country’s racism before ever facing the enemy, the training conducted with broken, outdated equipment, the harsh treatment by officers who expected them to collapse under pressure, the knowledge that the world doubted them before they had even fired a shot. They marched up the mountain carrying more than rifles and packs; they carried the weight of representing an entire race to an army, a nation, and an enemy who believed wholeheartedly that they were inferior.

Within forty-eight hours, Schellenburg—so assured in his ideological certainty—would send an urgent message to Field Marshal Kesselring’s headquarters. His report would force German commanders to confront realities that contradicted their carefully cultivated beliefs about racial hierarchies. The Germans had laughed. But their laughter would not survive the mountains.

This is the story of how the Buffalo Soldiers of World War II transformed from ridiculed stereotypes into the force that threatened to smash the Gothic Line.

The 92nd Infantry Division had been activated in October 1942 at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, a remote base where the sun scorched the earth and temperatures routinely soared above 110 degrees. Fifteen thousand Black soldiers, organized into four infantry regiments, began training there. Their shoulder patch—a black buffalo—paid homage to the legendary frontier regiments of the 19th century, the original Buffalo Soldiers who had fought on the American plains.

Yet that proud symbol could not erase the institutional obstacles that confronted them daily. The U.S. Army remained deeply segregated. Black soldiers lived in separate barracks, ate in separate mess halls, and were commanded almost entirely by white officers, many drawn from Southern states where segregation was woven into the laws and the culture. Private First Class Vernon Baker, who would later become the division’s most celebrated hero, remembered the open contempt. Some officers, he recalled, told them directly that colored soldiers could not fight, could not lead, and could not withstand the brutal pressures of combat. So the men trained twice as hard, knowing they would be given only half the credit.

Training at Fort Huachuca was brutal not only because of the assignments or the heat but because of the equipment. They drilled with World War I–era rifles long obsolete by modern standards. Ammunition was limited. Vehicles were unreliable. Their training felt like a test designed to break them while offering none of the tools needed to succeed. Staff Sergeant Edward A. Carter Jr. described it bitterly but with determination: They give us the oldest rifles, the worst trucks, and officers who’ve never seen combat. Then they wonder why we’re not ready. But we will be ready. We have to be.

Outside the base, the contradictions cut deeper. The towns surrounding Fort Huachuca enforced strict segregation. Black soldiers in uniform—men preparing to risk their lives for freedom on foreign soil—were routinely denied service in restaurants that welcomed German prisoners of war. Even enemy soldiers received more dignity than they did. The insult festered, but it hardened their resolve.

By June 1944, the division received its deployment orders. Their destination: Italy. Their mission: help break the Gothic Line. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring had spent two years preparing this line of interlocking mountain defenses—about 200 miles long—designed to block Allied advancement into Northern Italy. It included 2,376 machine-gun nests, 479 anti-tank positions, minefields stretching for miles, layers of barbed wire, and concrete fortifications buried into the mountainsides.

The Buffalo Soldiers would face all of this with inconsistent air support, inadequate artillery, and the painful awareness that if they failed, their failure would be used as proof of racial inferiority.

When the division landed in Naples in July 1944, they were placed under the command of General Edward M. Almond. His views about African American soldiers were well-known. He doubted their abilities, distrusted their competence, and surrounded himself with officers who shared his beliefs. Staff Sergeant Johnny Stevens later said that Almond told them plainly they needed to prove themselves, that people were watching them carefully. What Almond did not say, but what every soldier heard in the silence between his words, was the expectation of failure.

By December 1944, the Allied situation had become dire. The Gothic Line remained unbroken despite months of assaults. As winter deepened, General Mark Clark needed a breakthrough before the cold made offensive operations impossible. The assignment was given to the 92nd Infantry Division. Their target: the towering western anchor of the Gothic Line—Monte Belvedere.

Monte Belvedere climbed 3,830 feet into the sky, giving German artillery observers a view that stretched 50 miles in every direction. From its summit, German forces could target any movement in the valley below with terrifying precision. Von Schellenburg, commanding the 148th Grenadier Division, had personally supervised much of the defensive construction. He trusted the bunkers with their three-foot-thick concrete walls. He trusted the mortars hidden in camouflaged pits. He trusted the machine-gun nests positioned to control every slope.

German soldiers wrote home with confidence. One letter, from Leutnant Hans Becker, declared that the Americans would need wings to reach the summit—that the slopes were too steep to climb without enemy fire, and impossible to climb under it. The negro troops they’re sending, he wrote, will die before they reach our wire.

German intelligence reports echoed the same racist assumptions. A November 1944 assessment—based entirely on ideology, not observation—claimed that Negro units lacked combat motivation, that they would collapse upon meeting serious resistance, and that their white officers would fail to rally them. Training manuals even advised holding strong in the opening phase, insisting that Black soldiers would inevitably panic and flee.

This overconfidence shaped German defensive strategy. Schellenburg positioned his forces assuming the 92nd Infantry Division would break before they ever reached the main line of resistance.

Nature itself added to the German advantage. Temperatures fluctuated from barely tolerable during the day to punishing cold at night. Rain turned trails into rivers of mud. Fog snuffed out air support. Trench foot spread rapidly. In November alone, the 92nd recorded 847 cases serious enough to require evacuation.

Their artillery support was insufficient. Ammunition was short. Air support was rare. Doctrine demanded a 3-to-1 advantage when assaulting fortified positions; instead, the Buffalo Soldiers attacked at numbers equal to or fewer than the defenders.

But they marched anyway, aware that failure would strengthen every racist theory crafted to undermine them. They marched knowing they were not valued equally. They marched knowing the Germans expected their fear.

December 26th, 1944. Hour 0600. Darkness clung to the slopes, the ice slick beneath their boots, the German guns waiting above, the fog settling in layers so thick that the world seemed to vanish beyond arm’s reach.

The Buffalo Soldiers began their climb.

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

December 26th, 1944. Monte Belvadier, Northern Aenines, Italy. Through morning fog, Obus Hinrich von Shelonburgg watched American troops advancing toward his fortress. Negroes, his briefing officer, had reported with contempt. The Americans have sent us their weakest troops. Former railroad porters playing soldier.Von Shelonburgg, a Stalingrad veteran, studied the men through field glasses. The 370th Infantry Regiment, part of the US Army’s 92nd Infantry Division. An all black unit in a segregated army sent to assault the most formidable German defensive position in Italy, the Gothic line.

Vermacht propaganda had prepared German soldiers to expect quick surrender from black American troops. Nazi racial theories declared African soldiers inherently inferior in combat, lacking discipline and courage for sustained fighting. What Fon Shelonburgg didn’t know was that marching toward his mountain fortress were men who had endured challenges no German soldier could imagine.

They had fought racism in their own army, trained with inadequate equipment, and served under officers who expected them to fail. They carried a burden heavier than their packs, the weight of representing an entire race to a world that doubted them. Within 48 hours, Von Shelonburgg would send an urgent message to Field Marshall Kessle Ring’s headquarters.

A message that would force German commanders to reassess everything they believed about racial combat capabilities. The Germans had laughed, but the laughter died in the mountains. This is the story of how the Buffalo Soldiers of World War II transformed from objects of derision into the sledgehammer that cracked the Gothic line.

The 92nd Infantry Division activated in October 1942 at Fort Wuka, Arizona. 15,000 black soldiers organized into four infantry regiments. Their shoulder patch bore a black buffalo honoring the legendary buffalo soldiers of the frontier army.

But pride couldn’t overcome systematic obstacles. The US Army remained rigidly segregated. Black soldiers lived in separate barracks, ate in separate mess, and trained under predominantly white officers, many from southern states where segregation was law. Private first class Vernon Baker later recalled, “Some officers made it clear they expected us to fail.

They told us directly that colored soldiers couldn’t fight, couldn’t lead, couldn’t handle combat pressure. We trained twice as hard to prove them wrong, knowing we’d get half the credit. Training at Fort Wuka proved brutal. Temperatures exceeded 110° in Arizona’s desert. Yet the division received inferior equipment, World War I surplus rifles, limited ammunition, the worst vehicles.

Staff Sergeant Edward A. Carter Jr. wrote, “They give us the oldest rifles, the worst trucks, and officers who’ve never seen combat. Then they wonder why we’re not ready, but we’ll be ready. We have to be.” The Buffalo soldiers also faced racism beyond their posts. Towns near Fort Wuka enforced strict segregation.

Black soldiers in uniform were refused service at restaurants where German prisoners of war ate freely. The contradiction burned, fighting for freedom abroad while denied basic dignity at home. By June 1944, the division received deployment orders for Italy’s Gothic line, 200 m of fortifications that Field Marshal Kessle Ring had spent 2 years building.

The line incorporated 2,376 machine gun nests, 479 anti-tank positions, 120,000 m of barbed wire, and extensive minefields. The Buffalo soldiers would face this barrier with inadequate artillery support, inconsistent air coverage, and the burden of knowing that failure would confirm every racist stereotype. German propaganda already mocked their deployment.

Vermacht intelligence dismissed black American troops as third rate soldiers suitable only for labor duties. The division arrived in Naples in July 1944. General Edward M. Almond commanded a Virginia whose racial attitudes were well documented. He openly doubted his soldiers capabilities and maintained relationships with officers who shared his prejudices.

Staff Sergeant Johnny Stevens recalled, “General Alman told us we had to prove ourselves, that people were watching. What he didn’t say, but we all heard, was that he expected us to fail. That made us more determined than any pep talk could have. By December 1944, Allied commanders faced crisis. The Gothic line remained unbroken despite months of attacks. Winter approached.

General Mark Clark needed a breakthrough before snow made mountain warfare impossible. The mission given to the 92nd Infantry Division, assault the western anchor of the Gothic line, capture mountain peaks dominating the Cirio Valley, and drive German forces back. Success would open the door to northern Italy.

Failure would mean another winter of stalemate and confirmation of every racist assumption about black soldiers. The centerpiece of German defenses was Monty Belvadier, rising 3,830 ft above the Sergio Valley. From its summit, German observation posts could see 50 mi in every direction, calling artillery fire on any movement with devastating accuracy.

Oburst Fon Shelonberg, commanding the 148th Grenadier Division, had supervised construction personally. Concrete bunkers with three-foot walls protected machine gun crews. Mortars sat in covered pits invisible to aerial reconnaissance. The mountains multiplied German effectiveness. A single machine gun could control an entire valley.

Litant Hans Becker wrote to his wife, “The Americans would need wings to reach us. The slopes are so steep that climbing without enemy fire would be difficult. under fire. I cannot imagine how they could advance. The negro troops they’re sending will die before they reach our wire. German intelligence on the 92nd Infantry Division reflected Nazi racial prejudices.

A November 1944 assessment stated, “American Negro units lack combat motivation. They will advance until meeting serious resistance, then retreat or surrender. Division is suitable only for defensive operations or garrison duties. This wasn’t based on combat observation. It reflected Nazi ideology that declared non-arens inherently inferior.

Vermuck training manuals advised offer strong initial resistance. Negro troops will panic and flee. Their white officers will be unable to restore order. These assumptions created dangerous overconfidence. Von Shelonburgg positioned forces believing black troops would collapse under artillery fire, never reaching his main defensive line.

The Gothic Lines’s fortifications included esmines, bouncing betties that jumped 3 ft before exploding at groin height. Barbed wire obstacles some 30 ft deep forced attackers into killing zones. German defenders had registered every approach route with artillery. Weather became a German ally. November temperatures ranged from 40° during the day to below freezing at night.

Rain fell constantly, turning trails to mud. Morning fog prevented air support. Trenchoot became epidemic. The 92s medical reports showed 847 cases serious enough for evacuation in November alone. Allied artillery and air support proved inadequate. Ammunition shortages plagued Italian operations. The 92nd received only 30% of requested ammunition while priority went to France.

Air support averaged fewer than 10 sorties daily compared to 100 plus in northwest Europe. The Buffalo soldiers studied their objective knowing they would assault with inadequate preparation. They would attack at numerical para defenses. No 3:1 superiority that doctrine required. Success depended on courage, determination, and accepting casualties that would horrify commanders who valued their soldiers equally.

But these soldiers weren’t valued equally. They knew it. The Germans knew it. Failure would confirm every racist assumption. That burden was heavier than the equipment they carried. December 26th, 1944. Hour 0600. The attack would begin in darkness on ice covered slopes against an enemy expecting them to fail.

December 26th, 0545 hours, absolute darkness on Monty Belvadier’s lower slopes. Men of Company C, 370 Infantry Regiment checked equipment one final time. Every man carried 60 lb up slopes where mountain goats struggled. Staff Sergeant Carter whispered final instructions. Stay low until artillery stops. Watch for mines. When we reach the wire, Bangalore torpedoes go first. Follow me through.

If I go down, the next man takes over. We keep moving until we reach the top or we’re all dead. At 0600, American artillery opened fire. 2,400 rounds in 15 minutes, the maximum allowed. In his command bunker, Bonelenburgg smiled. Only 15 minutes. The Americans are weaker than we thought. The Negro troops are coming.

When artillery stopped, 30 seconds of silence. Then American voices shouted, “Move out.” And the Buffalo soldiers began their climb. The slopes averaged 45° angles, steep enough that soldiers grabbed vegetation and rocks to pull themselves upward. Some sections exceeded 60°. Men carried rifles slung, needing both hands to climb.

Combat loads became torturous after 100 yards of vertical ascent. Private James Hrix described it. You’d climb 10 steps and need to rest, gasping. Your legs burned. Your shoulders achd. You knew if you stopped too long, you’d never start again. So you climbed one step at a time, listening for the sound that meant Germans spotted you.

machine guns opening fire. That sound came at 6:23. German MG42s firing 1,200 rounds per minute swept slopes with interlocking fire. The first bursts caught company seized lead platoon 400 yd from the summit. Men dropped, some hit, others seeking cover that didn’t exist. Sergeant Carter saw three men cut down in the first seconds.

“Keep moving!” He shouted. They can’t hit what’s moving. Go. German mortar fire arrived next, walking down the mountain. But the Buffalo soldiers didn’t break. They kept climbing using fire and maneuver tactics that white officers assumed they couldn’t master. At 0647, Company C reached German wire.

Bangalore torpedoes blew gaps through defenses. Germans responded with grenades. Private Vernon Baker, leading his squad through a breach, encountered a German machine gun firing down the gap. Baker charged the position alone, killing the three-man crew with rifle fire and grenades. His squad rushed through, expanding the breach.

Company B, attacking from the northwest, faced even worse terrain, a 70° rock face requiring ropes. German defenders, assuming no one would attack there, left the sector lightly defended. Captain John Renan exploited this, leading his men up the cliff in darkness. At 0715, Company B’s lead elements reached the summit ridge.

The first Americans to penetrate the Gothic line’s main defenses. German defenders, shocked, fell back. But Renan’s company was isolated, exposed to counterattacks from three directions. Von Shelonberg refused to believe reports initially. Negro troops cannot have reached the summit. When confirmation came, his confidence shattered.

He ordered immediate counterattack. 120 elite assault troops. The counterattack hit at 0745. Hand-to- hand combat erupted in fog and smoke. Soldiers fought with rifle butts and entrenching tools when ammunition ran out. Staff Sergeant Ruben Rivers, leading a platoon, charged into enemy fire when Germans threatened to overwhelm his position.

He killed seven German soldiers with his bar before being killed himself. His sacrifice gave Company B time to reorganize and hold. By 08:30, the counterattack stalled. Company B still held their foothold. 34 killed, 52 wounded out of 97 who attacked, but they hadn’t broken. Germans expecting negro troops to flee faced soldiers fighting with ferocity that stunned them.

Lit Becker later wrote, “We killed many, but they kept coming. We threw them back, but they attacked again. These were not the weak soldiers our intelligence described. They fought like demons. We began to understand racial theories were lies, but learned this truth too late. Throughout the day, additional companies assaulted Monte Belvadier.

By 1400 hours, American soldiers held multiple summit positions. Artillery support improved as forward observers called fire from the peak. The 600th Field Artillery Battalion fired 1,800 rounds that afternoon. The battle raged through December 26th and 27th. German counterattacks came every few hours. Determined efforts to throw Americans off the summit.

Each was beaten back by soldiers who refused to descend defeated. Ammunition ran low. Food was non-existent. Water froze. Men fought on adrenaline and determination. By December 28th, the 371st Infantry Regiment controlled Monte Belvadier’s summit. Germans, recognizing they couldn’t dislodge Americans, withdrew to secondary positions.

The Gothic Lines western anchor was cracked. The cost was devastating. The 370th suffered 573 casualties out of 2,800 engaged. Company B was reduced to 31 effectives from 97, but they had succeeded where German commanders said negro troops must fail. Private Baker surveying the battlefield December 29th. Bodies everywhere.

Ours and theirs frozen where they fell. Some of our men climbed wounded, bleeding, dying, but still climbing because stopping meant the man behind you died. We proved something on that mountain. We proved we could fight. But my god, the cost. German assessments underwent immediate revision. A January 1945 intelligence report to Kessle Ring stated, “American Negro units demonstrate combat effectiveness equal to white divisions.

” Previous assessments based on racial theory were incorrect. These troops fight with determination and accept casualties that would break lesser units. January 1945 brought savage winter. Temperatures plunged to 10° at night. Snow accumulated to 3 ft. Wind speeds exceeded 40 mph, driving wind chill to minus 20.

Monte Castello, connected to Belvadier by narrow ridge, became the next objective. Germans reinforced after losing Belvadier. The assault began January 24th with critical support, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the decorated Japanese American unit attached to the division. The tactical plan reflected lessons learned. Night attacks would exploit American advantages while negating German artillery.

Most importantly, the offensive would continue regardless of casualties until objectives were secure. Lieutenant Colonel Virgil Miller briefed commanders. We are taking Monte Castello and holding it. Period. I don’t care how many counterattacks they throw. We’re staying on that mountain until relieved or dead.

Make sure your men understand there’s no falling back. The night attack jumped off at 0400 on February 19th. The 442nd struck from the north while the 370th assaulted from the east. The combination of Japanese Americans fighting to prove loyalty and black soldiers fighting to prove equality created overwhelming force. By 0630, both units reached Monte Castello’s summit simultaneously.

German defenders attempted counterattacks but faced attackers already dug in. Positions that had dominated approaches for months were overrun. Von Shelonburg sent urgent message to Kessle Ring. Monte Castello lost. American negro and Japanese units fighting with exceptional determination. Gothic line western sector compromised.

Request permission to withdraw. Kessler denied it. Hold at all costs. Monte deaachia must not fall. But Vonelenberg knew his position was untenable. The final assault on Montela Tarachia came February 21st. Three regiments supported by the 442nd British artillery and for the first time in weeks clear weather allowing air support.

P47s strafed German positions while B25s dropped 500 lb bombs on bunkers. The combined assault shattered German resistance in 6 hours. By 1800 on February 21st, American soldiers controlled all three peaks. The Gothic lines western anchor had fallen to troops German propaganda said couldn’t fight. The cost was staggering. December 26th through February 21st, the 92nd suffered 2,187 casualties, 419 killed, 1,611 wounded, 157 missing.

Individual companies reduced to 40% strength. But German losses were catastrophic differently. They lost positions that could never be retaken. The Gothic line’s integrity was broken. Kessle Ring’s defensive masterpiece had a gaping wound through which Allied forces would pour. A captured German officer interrogated. February 23rd.

We were told colored soldiers would run at first shot. Instead, they climbed mountains under fire that should have stopped any attack. They suffered casualties that would have broken German units and kept advancing. I fought Soviet guards divisions on the Eastern Front. These negro soldiers fought just as hard, maybe harder, because they seem to have something to prove.

With the Gothic line broken, Fifth Army’s spring offensive exploited gaps, driving toward the Po Valley and forcing German surrender in Italy on May 2nd, 1945. But the broader significance transcended military operations. The Buffalo Soldiers shattered assumptions about race and combat capability that had persisted for generations.

They proved that when given adequate support and opportunity, black soldiers performed at the same level as any troops in the world. Recognition came slowly. Seven members earned the Medal of Honor, though six awards weren’t approved until the 1990s. Vernon Baker, whose courage on Monty Belvadier was undeniable, received the Distinguished Service Cross in 1945.

Downgraded from Medal of Honor recommendation. Only in 1997, 52 years later, was his award upgraded. He was the only living recipient among the seven. General Mark Clark’s assessment reflected the era’s racial attitudes. The 92nd Infantry Division has performed creditably. Their success demonstrates that with proper training and leadership, Negro troops can contribute meaningfully to combat operations.

Field Marshal Kessler’s postwar memoirs showed greater honesty. The American Negro divisions in Italy fought with distinction. Our intelligence assessments based on racial theories were completely wrong. These soldiers demonstrated courage equal to any forces I faced in my career.

The soldiers returned to an America where victory abroad hadn’t won equality at home. Black soldiers who fought through the Gothic line came home to segregated buses, Jim Crow laws, and legal discrimination. Many were denied GI Bill benefits. Some were attacked for wearing uniforms in southern states. Private Hrix, who survived Monty Belvadier, was refused service at a Georgia diner 3 months after returning.

When he protested, showing his combat infantryman’s badge and purple heart, police beat him. “I took Monty Belvadier,” Hendrick said years later. “But I couldn’t get a hamburger in my own country. Yet the legacy endured. Their success contributed to arguments for military integration. President Truman’s Executive Order 9981 in 1948, which desegregated the armed forces, cited black units combat record as evidence segregation weakened military effectiveness.

Vernon Baker, receiving his Medal of Honor in 1997 at age 77, addressed the ceremony directly. The award is welcome, but it’s 52 years late. Seven of us earned this honor. Six had to die before America saw fit to give it to them. That tells you everything about the country we fought for and the country we came home to. Today, Monte Belvadier stands quiet.

A memorial erected in 1995 bears the names of those who died. The inscription is simple. They proved themselves here. Baker, interviewed before his 2010 death, was asked what he wanted people to remember. Remember that we volunteered to fight for a country that treated us as secondclass citizens. Remember that we proved ourselves against an enemy who thought we were inferior while serving in an army that agreed.

Remember that we took mountains white units had failed to take, then came home to a country where we couldn’t vote, couldn’t get jobs, couldn’t live where we wanted. But remember most of all that we did it anyway. We fought anyway. We proved ourselves anyway. The story of the 92nd Infantry Division is ultimately about human dignity and refusing to accept limitations imposed by prejudice.

The Buffalo soldiers climbed those mountains carrying the aspirations of millions of black Americans demanding recognition of their full humanity. The Germans laughed at the deployment of black troops to Monte Belvadier. But the laughter died in the mountains, drowned out by men who refused to quit, refused to break, refused to accept anyone’s judgment of their worth except their own. They were told they couldn’t fight.

They were given the worst assignments. They were expected to fail. Instead, they took the mountain, broke the line, and changed history. The Germans had laughed. The Buffalo Soldiers had the last

News

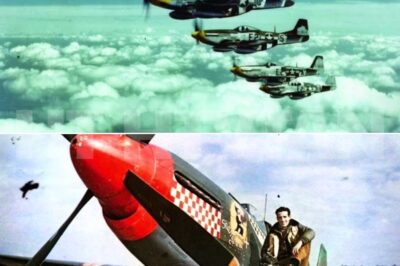

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

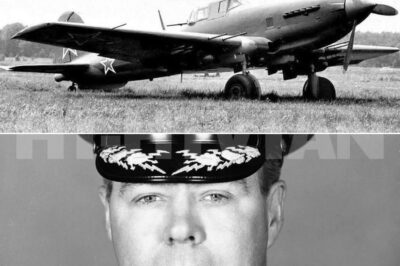

CH2 . America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped as North Korean fighters strafe the runway, destroying transports one by one. Enemy armor is twenty miles away and closing. North Korean radar picks up five unidentified contacts approaching from the sea. The flight leader squints through his La-7 canopy.

America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped…

CH2 . Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above Cape Bon, Tunisia.

Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above…

CH2 . Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles northwest of Lelay, New Guinea. The oil blackened hand trembled as a Japanese naval officer gripped the splintered remains of what had once been part of the destroyer Arashio’s bridge structure. His uniform soaked with fuel oil and seaater, recording in his mind words that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles…

CH2 . Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on April 18th, 1942 fundamentally altered the Pacific Wars trajectory, forcing Japan into a defensive posture that would ultimately contribute to its defeat.

Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on…

CH2 . German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of December 1944, the German war machine, a beast long thought to be dying, had roared back to life with a horrifying final fury. Hitler’s last desperate gamble, the massive Arden offensive, known to history as the Battle of the Bulge, had ripped a massive bleeding hole in the American lines.

German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of…

End of content

No more pages to load