Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes…

April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above Cape Bon, Tunisia. The afternoon sun cast long shadows across the Mediterranean as one of the most lopsided air battles in history was about to unfold. Within minutes, the Luftvafa would lose between 24 and 59 transport aircraft, sources differ on exact numbers, in what American pilots would call the Palm Sunday Massacre.

German records would confirm 24 G52 transports destroyed and 35 damaged, while American claims ranged from 50 to 70 aircraft destroyed. But the discrepancy in numbers mattered less than the psychological impact. In approximately 15 minutes of combat, American P40 Warhawks demonstrated air superiority so complete that German assumptions about the war’s outcome began to crumble.

The engagement would pit 47 P40 Warhawks and 12 RAF Spitfires against 65 German Due 52 transports escorted by approximately 15 BF 109s and four to five BF10s. The result would be catastrophic for the Luftwaffer. At least 24 transports confirmed destroyed, 35 damaged, and nine BF109s and one BF-11’s shot down against American losses of six P40s and one Spitfire.

This devastating kill ratio represented not just tactical victory, but the revelation of American air supremacy that German military doctrine had deemed impossible. What the Germans flying that Palm Sunday afternoon didn’t know was that ultra intelligence had compromised their every communication, that American pilots had trained specifically for this moment, and that the industrial democracy they had been taught to despise had produced warriors capable of systematic, efficient destruction.

By April 1943, the Africa Cor’s position in Tunisia had become desperate. Trapped between Montgomery’s eighth army advancing from the east and American forces pushing from the west. Roughly 250,000 German and Italian troops depended entirely on aerial supply. The Mediterranean had become a graveyard for axis shipping. Allied forces operating from Malta were sinking vessels at an unsustainable rate.

Operation Flax, the Allied effort to sever this aerial lifeline had begun on April 5th, 1943. Unlike previous sporadic interceptions, flax represented systematic interdiction based on ultra intelligence. Allied codereers at Bletchley Park were reading German communications in near real time, providing American and British squadrons with detailed information about transport schedules, routes, and escort strength.

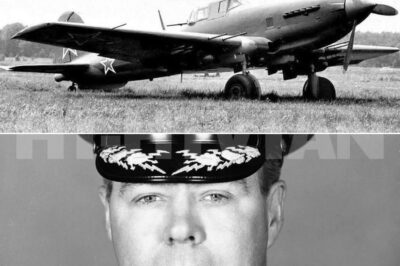

The Luftvafer had assembled every available transport aircraft for the Tunisia supply runs. The backbone of this effort was the Joner’s U52 tri motor, a reliable workhorse that had served German forces from Spain to Cree. By April 1943, these transports were flying multiple daily missions from Sicily to Tunisia, each aircraft carrying vital supplies or evacuating wounded and specialist personnel.

The Germans believed their transport operations remained relatively secure. They flew at extremely low altitude, often just 50 ft above the water to avoid radar detection. Fighter escorts from elite units like JG27 and JG53 provided protection. The timing of missions was varied to prevent predictable patterns.

Yet all these precautions were futile when the enemy could read your communications. On the afternoon of April 18th, 1943, a large German transport formation was returning to Sicily after delivering supplies to Tunisia. The formation consisted of 65 J52 transports flying in tight defensive formations escorted by experienced fighter pilots from second squadron JG27 and elements of JG53.

These escort pilots were veterans of the Desert War, many with dozens of victories. The Escort faced a fundamental limitation that would prove fatal, fuel capacity. Operating at maximum range, the BF109s had perhaps 20 to 30 minutes of combat fuel when over Cape Bon. Any sustained engagement would force them to break off or risk ditching in the Mediterranean.

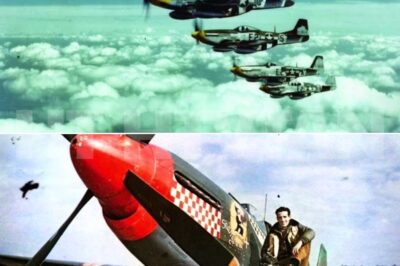

This constraint, known to Allied intelligence through ultra intercepts, would be ruthlessly exploited. On the Allied side, the 57th Fighter Group had been preparing for this moment. Based at LGM in Tunisia, they had spent weeks training for large-scale transport interception. The group would commit all its squadrons to the operation, joined by the 314th Fighter Squadron of the 324th Fighter Group, totaling 47 P40 Warhawks.

Above them, 12 Spitfires from 92 Squadron RAF, would provide top cover. The P40 Warhawk, while not the most advanced American fighter, had been systematically improved for Mediterranean operations. Modified superchargers allowed better altitude performance, while the 650 caliber machine guns had been harmonized for maximum effectiveness at 250 yd, optimal range for transport interception.

At approximately 1,500 hours, the German formation was spotted flying northeast towards Sicily at extremely low altitude. Reports vary from 50 to 1,000 ft. The transports flew in tight V formations, a defensive arrangement that had provided mutual protection in previous conflicts against concentrated fighter attack. However, this formation would become a death trap.

The Allied fighters had positioned themselves perfectly. The P40s approached at around 4,000 ft while the Spitfires maintained top cover at 15,000 ft. The setting sun was behind the Allied fighters, making them difficult to spot until too late. The German formation, flying low over the water, was silhouetted against the sea, making them easy targets.

When the Allied fighters struck, the German escort faced an impossible choice. Climbing to engage meant burning precious fuel and abandoning the transports. Staying low meant seeding altitude advantage to the attackers. The escort commander chose to engage, ordering his fighters to climb and intercept the Americans.

It was a brave decision, but ultimately futile. The battle that followed was less combat than execution. American P40 doves dove on the transport formation in successive waves, each pilot selecting targets and attacking with mechanical precision. The defensive armorament of the G52s, typically one 13 mm machine gun in a dorsal position and two 7.

92 mm guns in beam windows, proved wholly inadequate against the devastating firepower of 650 caliber machine guns. According to Allied pilot reports, passengers in the German transports attempted to defend their aircraft with personal weapons, rifles and machine guns pistols fired through windows. This desperate resistance, while courageous, was futile against fighters making high-speed passes.

The thin aluminum skin of the G52s offered no protection against 050 caliber rounds. The German fighter escort fought desperately, but was overwhelmed by numbers and tactical disadvantage. The Spitfires engaged them at altitude while P4s continued to savage the transports below. German pilots later reported the frustration of watching their charges being destroyed while they fought for their own survival against superior numbers.

Within minutes, the sea below was littered with burning wreckage. Some transports exploded in midair, others crashed into the water, and many attempted crash landings along the Sicilian coast. German sources would later confirm 24 G52s destroyed outright and 35 damaged. many so severely they never flew again. German records documented the casualties from the transport aircraft.

20 air crew killed, 28 wounded, and 50 missing, though these numbers likely represent only flight crew and may not include passengers. The transports were carrying more than just pilots and crew. They held ground personnel, administrators, wounded soldiers being evacuated, and specialist technicians whose expertise was irreplaceable.

Each destroyed transport represented not just material loss, but human tragedy. These were not combat troops, but support personnel, mechanics who maintained aircraft, communications specialists who operated radios, medical staff evacuating wounded. Their loss would German operations as surely as the destruction of combat units.

American losses were comparatively light, six P40s and one Spitfire, with their pilots either killed or captured. This stark disparity in losses, a kill ratio of at least 4:1 and possibly as high as 10:1 depending on which figures are used, demonstrated the complete tactical superiority achieved by the Allied forces.

Declassified documents have revealed the crucial role of ultra intelligence in the Palm Sunday massacre. Allied codereakers had provided complete details of the German transport schedule days in advance. American planners knew the number of aircraft, their routes, escort strength, and even cargo manifests. This intelligence advantage allowed optimal positioning of intercepting forces.

The Allied fighters were already at altitude and in position when the Germans appeared. Fuel loads were calculated precisely for extended combat. Even the ammunition mixture, armor piercing, incendiary, and tracer rounds, was optimized for destroying transport aircraft. The Germans never suspected their communications were compromised.

Postwar interrogations revealed German commanders believed the interception was either lucky coincidence or the result of coast watchers. The possibility that Enigma had been broken never occurred to them, allowing the allies to continue exploiting this advantage throughout the war.

At Luftvafer headquarters in Rome, initial reports of the disaster were met with disbelief. Staff officers assumed the numbers were exaggerated or that panic had led to confusion. As confirmation arrived from multiple sources, surviving aircraft, Italian observers, German naval units picking up survivors, the scale of the catastrophe became undeniable.

General Feld Marshall Albert Kessler, commanding German forces in the Mediterranean, immediately suspended daylight transport operations. His war diary for April 18th contains a tur entry. Daylight transport operations have become impossible. Night operations only until further notice. Hitler’s reaction was predictably extreme.

He demanded courts marshall for the escort commanders, accused the transport pilots of cowardice, and ordered immediate reinforcement of Mediterranean fighter strength, orders that were impossible to fulfill given stretched German resources. The Palm Sunday massacre effectively ended German daylight aerial supply to Tunisia.

Combined with the interdiction of seaw routts, this severed the Africa cor supply line at a critical moment. Units that had maintained defensive positions despite material shortages now faced complete logistical collapse. General Hans Jurgen Fonim, commanding Army Group Africa, recognized the implications immediately. Without aerial resupply, his forces could hold for weeks at best.

The surrender of Axis forces in North Africa on May 13th, 1943, less than a month after Palm Sunday, was accelerated by the transportation crisis created by the massacre. Beyond immediate tactical effects, Palm Sunday demonstrated American air superiority in the Mediterranean. German forces that had depended on Luftvafer support for every operation now knew they would fight without air cover.

This psychological blow affected morale throughout the Vermachar. The Palm Sunday massacre revealed technological disparities that shocked German participants. The P40 Warhawk, which German intelligence had classified as obsolete, demonstrated capabilities beyond German expectations. Modified engines allowed operations at altitudes Germans thought impossible for the type.

Improved gun sites provided accuracy that seemed impossibly precise, according to German reports. More fundamentally, American radios worked reliably. Every P40 pilot could communicate clearly with wingmen and flight leaders, allowing coordinated attacks impossible for German formations plagued by radio failures. This basic technological advantage, reliable communication, translated directly into tactical superiority.

American maintenance and logistics also proved superior. The P40s operating over Cape Bond had been maintained at high operational readiness despite desert conditions. Spare parts were abundant, fuel was plentiful, and ammunition was never in short supply. German units, by contrast, struggled with chronic shortages of everything.

Perhaps the most decisive factor was the vast gap in pilot training. American pilots participating in Palm Sunday averaged over 300 flight hours before entering combat. They had practiced formation flying, gunnery, navigation, and combat tactics in the safe skies of the United States. They arrived in theater already proficient in their aircraft.

German pilots, by contrast, were products of an increasingly abbreviated training program. Fuel shortages meant minimal flight hours. Instructor pilots were pulled into combat units. Training aircraft were requisitioned for operations. The systematic training that had produced the Luftvafer’s early excellence had collapsed under the pressures of multiffront war.

This disparity would only worsen as the war continued. By late 1943, American pilots would average 400 hours of training, while Germans averaged 80. The Palm Sunday massacre was not an aberration, but a preview of the Luftvafer’s systematic destruction. Palm Sunday was not an isolated incident, but part of the sustained operation flax campaign.

On April 5th, Allied fighters had already destroyed 14 J 52s and damaged many others. On April 10th, another sweep netted 20 transports. On April 19th, the day after Palm Sunday, South African Air Force squadrons shot down 16 Italian SM82 transports. The culmination came on April 22nd when Allied fighters intercepted a formation of MI323 Gigants, massive six engine transports that were the largest aircraft in the Mediterranean theater.

14 of 16 gigants were destroyed, each carrying 12 tons of desperately needed fuel. Of 138 crew members aboard the Gigants, only 19 survived. These cumulative losses, over 100 transport aircraft in less than 3 weeks, crippled German aerial supply capability, not just in the Mediterranean, but across all theaters. The Luftvafa transport fleet never recovered from the losses sustained during operation flax.

The Palm Sunday massacre marked a turning point in the Luftvafer’s effectiveness. The transport losses were irreplaceable, but more damaging was the loss of experienced crew. Each destroyed Jew 52 typically carried a pilot with hundreds or thousands of hours of experience, a co-pilot, and a radio operator/gunner. expertise that took years to develop.

The psychological impact on Luftwafa morale was devastating. Transport pilots who had operated with relative impunity early in the war now knew they were flying death traps. Fighter pilots knew they couldn’t protect their charges. Ground forces knew they couldn’t depend on aerial resupply. Within the German high command, Palm Sunday forced recognition that the air war was lost.

If the Luftwaffer couldn’t protect transport aircraft in daylight, how could it defend German cities from the bomber offensive that was clearly coming? The massacre over Cape Bon preaged the destruction that would reign on Germany itself. For American forces, Palm Sunday was vindication of their entire approach to warfare.

Systematic training, technological superiority, and industrial production had produced tactical dominance. Young Americans, products of a democratic society that Nazi ideology dismissed as weak, had demonstrated lethal efficiency. The 57th Fighter Group received a distinguished unit citation for the action.

Individual pilots who had scored multiple victories became aces in a single engagement. But beyond official recognition, Palm Sunday gave American pilots confidence that would carry through the rest of the war. The massacre also validated American tactical doctrine. Rather than emphasizing individual heroics, American training stressed teamwork, fire discipline, and mission accomplishment.

This systematic approach, derided by some as lacking warrior spirit, had proved devastatingly effective. Both sides used Palm Sunday for propaganda, though with vastly different effectiveness. American news reels showed gun camera footage of German transports exploding with titles like Easter egg hunt over Tunisia and Luftvafa’s Black Sunday.

The footage, while sanitized, conveyed American air superiority dramatically. German propaganda struggled to explain the disaster. Initial attempts to deny the losses collapsed when neutral observers confirmed American claims. Attempts to blame Italian treachery or mechanical failure were undermined by survivor testimony.

Eventually, German propaganda portrayed the losses as heroic sacrifice with transport crews dying to supply surrounded comrades. Within the Vermacht, however, the truth spread quickly. Soldiers made dark jokes about the Luftvafer’s Easter eggs that cracked at first touch. Songs mocking German intelligence became popular. The myth of Luftvafa superiority, carefully cultivated since Spain died over Cape Bon.

The Palm Sunday Massacre’s effects extended far beyond immediate tactical results. Hitler, shocked by the losses, diverted fighters from the Eastern front to the Mediterranean, weakening German forces before the crucial battle of Kursk. The Americans, emboldened by success, accelerated plans for the invasion of Sicily and daylight bombing of Germany.

Within German military circles, Palm Sunday became a case study in the danger of underestimating American capabilities. Officers who had dismissed Americans as amateur warriors were forced to recognize that American industrial and organizational capabilities had produced highly effective military forces. The massacre influenced German officers who would later participate in resistance against Hitler.

The demonstration of American military superiority convinced many that the war was unwinable. If America could achieve such dominance in the Mediterranean, what would happen when their full strength reached Europe? Military historians consider the Palm Sunday Massacre one of the most one-sided air battles of World War II. While the exact number of German aircraft destroyed remains debated, German records show 24 J52s destroyed and 35 damaged, while American claims ranged up to 70 destroyed.

The tactical and strategic impact is undeniable. The engagement demonstrated several principles that would define air warfare for the remainder of the conflict. Intelligence superiority enables tactical surprise. Technological advantages must be systematically exploited. Training quality matters more than combat experience.

Coordination beats individual excellence. And industrial capacity translates directly into combat power. Modern air forces study Palm Sunday as an example of successful interdiction operations. The systematic destruction of enemy transport capability achieved through intelligence, planning, and execution remains a model for contemporary air campaigns.

The Palm Sunday Massacre raises uncomfortable questions about the nature of modern warfare. The German transports were legitimate military targets carrying supplies to enemy forces. Yet they were also filled with human beings, many of them non-combatants like medical personnel and administrators who died horribly.

American pilots who participated carried complex emotions about their victory. They had done their duty effectively, but many were troubled by the one-sided nature of the engagement. Shooting down nearly defenseless transports, while necessary, lacked the honor of fighter versus fighter combat. These moral complexities reflect the transformation of warfare from individual combat to industrial destruction.

The Americans had not sought glory but accomplished a mission. They had killed efficiently, systematically, without hatred, but also without mercy. This was modern war, impersonal, technological, and devastatingly effective. The Palm Sunday Massacre offers enduring lessons for military professionals. First, intelligence superiority can enable tactical victories disproportionate to forces engaged.

Second, air superiority, once achieved, permits systematic destruction of enemy logistics. Third, industrial capacity and training infrastructure are decisive in prolonged conflicts. The engagement also demonstrates the vulnerability of air transport operations without air superiority. Modern militaries observing Palm Sunday have invested heavily in defensive systems for transport aircraft and emphasized the need for air superiority before attempting large-scale aerial logistics.

Finally, Palm Sunday shows how quickly air superiority can shift. The Luftwaffer, which had dominated European skies from 1939 to 1941, found itself helpless over Cape Bon in 1943. No advantage in warfare is permanent. Continuous adaptation and innovation are essential. The Palm Sunday Massacre was over in approximately 15 minutes, but its implications resonated through the remainder of World War II and beyond.

In those brief minutes over Cape Bon, American fighters didn’t just destroy German aircraft. They demonstrated the emergence of American air power as the dominant force it would remain for the rest of the century. The Germans, who couldn’t believe Americans had shot down so many planes so quickly, were experiencing more than tactical surprise.

They were witnessing the demonstration of a new military reality. Industrial democracy, fully mobilized and properly led, could generate combat power beyond anything authoritarian regimes could match. The massacre proved that technological superiority, systematic training, and industrial capacity could overcome experience, individual skill, and ideological fervor.

The Americans had turned warfare into science, and science was proving superior to the warrior mystique that had carried German forces to early victories. The Palm Sunday massacre stands as a watershed moment in aerial warfare. In approximately 15 minutes on April 18th, 1943, American fighters destroyed or damaged between 59 and 70 German aircraft.

The exact number matters less than the psychological impact. The Luftvafa’s transport capability in the Mediterranean was shattered, contributing directly to the collapse of Axis forces in North Africa. More significantly, Palm Sunday demonstrated American military doctrines effectiveness.

the systematic approach to training, the emphasis on technological superiority, the integration of intelligence into operations, and the industrial capacity to sustain combat operations had produced tactical dominance. Young Americans, dismissed by Nazi ideology as products of a weak democracy, had proved themselves lethal warriors.

The Germans, who couldn’t believe the scale of their losses, were confronting more than tactical defeat. They were witnessing the emergence of American military supremacy that would define the remainder of the war and the postwar era. The industrial democracy they had mocked had produced warriors more effective than Nazi ideology could imagine.

For military professionals, Palm Sunday remains a case study in the effective application of air power. Intelligence superiority enabled tactical surprise. Technological advantages were systematically exploited. Superior training proved decisive and industrial capacity translated directly into combat effectiveness. The transport pilots who took off from Tunisia that Palm Sunday afternoon expected a routine flight back to Sicily.

Their fighter escort, veterans of years of combat, were confident in their ability to protect their charges. Within 15 minutes, that confidence was shattered along with their aircraft. The Americans had not just won a tactical victory. They had demonstrated a new form of warfare that would dominate the remainder of the century. The Palm Sunday Massacre was brief, approximately 15 minutes of intense combat.

But in those 15 minutes, the nature of air warfare changed forever. The age of individual warrior heroes was ending. The age of systematic technological air power had arrived. The Germans, who couldn’t believe what had happened, were right to be shocked. They had witnessed not just their own defeat, but the birth of American air supremacy that would reshape the world.

In the end, the Palm Sunday Massacre proved a fundamental truth of modern warfare. Victory belongs not to the bravest or most experienced, but to those who can most effectively combine intelligence, technology, training, and industrial capacity into overwhelming combat power. On April 18th, 1943, over the beautiful blue waters of the Mediterranean, American fighters demonstrated this truth with devastating clarity.

The Germans could not believe it, but belief was irrelevant. The planes were destroyed, the men were dead, and the war’s outcome was increasingly certain. The legacy of those 15 minutes over Cape Bon continues to influence military thinking. Air Forces worldwide study the engagement, learning lessons about the importance of air superiority, the vulnerability of transport aircraft, and the decisive impact of intelligence in modern warfare.

The Palm Sunday Massacre was not just a tactical victory. It was a demonstration of how wars would be fought and won in the modern

News

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

CH2 . America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped as North Korean fighters strafe the runway, destroying transports one by one. Enemy armor is twenty miles away and closing. North Korean radar picks up five unidentified contacts approaching from the sea. The flight leader squints through his La-7 canopy.

America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped…

CH2 . Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles northwest of Lelay, New Guinea. The oil blackened hand trembled as a Japanese naval officer gripped the splintered remains of what had once been part of the destroyer Arashio’s bridge structure. His uniform soaked with fuel oil and seaater, recording in his mind words that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles…

CH2 . Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on April 18th, 1942 fundamentally altered the Pacific Wars trajectory, forcing Japan into a defensive posture that would ultimately contribute to its defeat.

Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on…

CH2 . German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of December 1944, the German war machine, a beast long thought to be dying, had roared back to life with a horrifying final fury. Hitler’s last desperate gamble, the massive Arden offensive, known to history as the Battle of the Bulge, had ripped a massive bleeding hole in the American lines.

German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of…

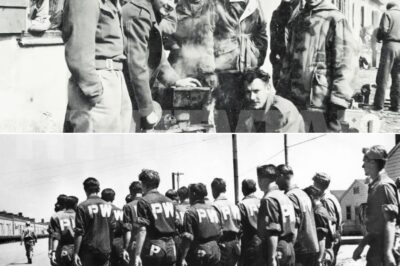

CH2 . German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary, recording words that would have earned him solitary confinement if discovered by his own officers. The Americans must be lying to us. No nation could possess such abundance while fighting a war on two fronts.

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street,…

End of content

No more pages to load