German Scared POWs Women Clung to Each Other Until Soldiers Prepared Hot Baths to Calm Their Terror…

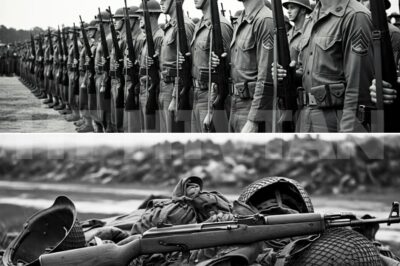

April 19th, 1945 dawned cold and gray over the shattered landscape of central Germany. And in a makeshift detention compound near the town of Lindberg, 73 German women prisoners of war crouched against wooden barrack walls, their eyes hollow with terror that went far deeper than the physical exhaustion etched into their faces. They had heard the stories whispered rumors that traveled through the crumbling Reich like poison in the bloodstream. Soviet soldiers advancing from the east, vengeful and brutal. And now American forces closing in from the west. The propaganda minister Joseph Gobles had broadcast relentlessly over the radio had painted vivid horrifying pictures of what Allied soldiers would do to German women when they arrived.

Mass violations, executions, torture beyond imagination. Greta Hoffman, 32 years old, pressed herself into the corner of the barracks. her Vermached auxiliary uniform torn and filthy from weeks of retreat. She had served as a communications officer at a command post in the Rhineland until the entire structure of German military organization had collapsed like a house of cards.

Now she was simply a prisoner waiting for a fate she believed would be worse than death. Beside her, 24year-old Elsa Brown, no relation to the infamous woman in Hitler’s bunker clutched the hand of an older woman named Margaret Klene, a former nurse who had worked in field hospitals on the Eastern Front, Margaret. Stories of what she had witnessed there, the wholesale destruction of entire villages.

The treatment of Russian civilians had filled them all with a particular dread. They knew what Germany had done. Now they expected payment in kind. The sound of approaching vehicles sent a wave of panic through the barracks. Women began to weep openly. Some prayed.

Others simply stared at the walls with the blank expression of those who had already surrendered to their imagined fate. “They’re here,” someone whispered, and the words carried the weight of a death sentence. The compound gate creaked open. Heavy boots crunched on gravel.

American voices called out in English, words the women couldn’t understand, but whose tone seemed impossibly casual for what they assumed would follow. Grad’s heart hammered so violently she thought it might break through her ribs. The barracks door swung wide and spring sunlight flooded in momentarily blinding them. Silhouetted in the doorway stood an American officer, tall and broad-shouldered, wearing the uniform of the United States Third Army. behind him. Several enlisted men carried what appeared to be equipment and supplies.

According to historical documentation preserved in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, the scene that followed would become one of thousands of small moments of unexpected humanity that punctuated the final weeks of the European War moments that complicated the simple narratives of victors and vanquished occupiers and occupied.

The officer removed his helmet. His face was young, perhaps 28 or 30, with tired eyes that had seen too much combat. He surveyed the terrified women before him, and seemed to understand immediately what they expected.

“We’re not going to hurt you,” he said in slow, careful English, though he knew most of them couldn’t understand the words. His tone, however, carried its own translation. He turned to a sergeant beside him, “Get the medical team in here, and somebody find us an interpreter.” Within the hour, the American soldiers had established what Captain James Morrison of the Third Army Civil Affairs Section would later describe in his official report as humanitarian processing operations for the female prisoners.

The women watched with confused, suspicious eyes as G is hauled in canvas tents, portable heating units, and wooden crates stamped with Red Cross insignia. An interpreter arrived, a German American corporal named Hinrich Vber from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, whose family had immigrated in 1923.

He was a stocky man with kind eyes and the particular gentleness of someone who understood both worlds meeting in this ruined landscape. Ladies, Vber called out in German, his accent carrying traces of both Wisconsin and Bavaria. The American command wants you to understand that you are under the protection of the United States Army. You will not be harmed.

You will be processed according to the Geneva Conventions and treated with respect. The women stared at him as though he were speaking an incomprehensible language, which in a sense he was. The gap between what they had been told to expect and what he was promising seemed impossible to bridge.

Greta Hoffman found her voice first horse from disuse and fear. What will you do with us? Vber translated for Captain Morrison who stepped forward. We’re going to take care of you, Morrison said through the interpreter. First, we need to get you cleaned up and fed. There are medical personnel here to check anyone who’s sick or injured.

Then we’ll work on getting you processed and figuring out where you’ll go next. That’s all. Elsa Brown whispered, disbelief sharp in her voice. Morrison seemed to understand the question even before Vber translated it. He looked at the assembled women exhausted, terrified, expecting the worst, and something shifted in his expression.

Perhaps he thought of his own mother back in Ohio or his sisters, or simply saw clearly the human cost of the war’s final collapse. That’s all he confirmed. Your prisoners of war, not criminals. We’re not monsters. The first practical problem was basic hygiene. The women had been without proper washing facilities for weeks, some even longer. Their uniforms were caked with mud and worse.

The smell in the barracks was overwhelming. A mixture of unwashed bodies, fierce, sweat, and sickness. Morrison ordered his men to set up field shower facilities, canvas enclosures with portable water heaters that the army used for frontline troops. It was an unusual allocation of resources at a time when the American advance into Germany was still consuming massive amounts of supplies, but Morrison had seen enough human misery. The cost of a few hundred gallons of heated water seemed a small price for basic human

dignity. We’re going to set up bathing facilities, VBR announced to the women. Hot water, soap, clean towels. You’ll go in small groups with privacy. There will be female nurses present to help anyone who needs assistance. The announcement was met with stunned silence. Hot water, privacy, nurses instead of soldiers. It didn’t match the narrative that had been drilled into them for months.

Margaretti Klene, the former nurse, was the first to speak. Why would you do this? Vber translated the question and Morrison considered it for a long moment before answering. Because it’s the right thing to do, he said simply. And because this war is almost over. What comes after matters.

The first group of women approached the shower enclosures as though walking toward their own executions. Despite Vber’s assurances and the presence of American Red Cross nurses, particularly a nononsense woman from Tennessee named Helen Crawford, who had served in field hospitals from Normandy to the ren the terror that had been cultivated by months of propaganda did not simply evaporate.

Greater Hoffman was in this first group along with nine other women, including young Elsa. They moved slowly, forming a tight cluster as though their proximity to one another might offer protection. When they reached the canvas structures, nurse Crawford pulled back the flap to reveal something wholly unexpected.

Steam rising from actual hot water, bars of white soap stacked on a wooden table, and clean towels folded neatly beside them. “Good Lord,” Crawford muttered to her colleague, a nurse named Patricia Mills from Oregon. “They look like they’re expecting us to shoot them. Can you blame them?” Mills replied quietly.

after what their own propaganda’s been telling them. Crawford stepped forward and addressed the women in the handful of German phrases she had picked up during her months in Europe. Her accent was atrocious, but the intent was clear. She gestured to the water, the soap, the towels. Then she did something remarkable.

She rolled up her own sleeve and stuck her hand in the water, pulling it out to show them it was simply water. Warm, clean, nothing sinister. The gesture was so absurd, so maternal that Margarthy Klene actually laughed, a short, sharp sound of surprise that seemed to startle even herself. “It’s real,” Margarith said to the others in German. “It’s actually just a bath.

” Historical records maintained by the United States Army Heritage and Education Center in Carlilele, Pennsylvania, contain numerous accounts of similar scenes throughout Germany in the spring of 1945. As American forces encountered not just military prisoners, but thousands of displaced persons, civilian refugees, and former concentration camp inmates, the provision of basic hygiene facilities became a standard component of humanitarian operations, though it was often overlooked in the broader historical narrative of the war’s

conclusion. Slowly, tentatively, the women began to undress. The nurses maintained respectful distances, offering assistance only when needed. Greta stepped under the first stream of hot water and felt something break inside her chest. Not physically, but emotionally, the water was actually hot, actually clean.

She had not felt hot water on her skin in so long that she had almost forgotten what it felt like. She began to cry around her. Other women were having similar reactions. Elsa stood under her own stream of water with her hands pressed to her face, shoulders shaking.

The weeks of accumulated terror, the bone deep exhaustion of Germany’s collapse, the confusion of finding mercy where they had expected brutality, all of it came flooding out in those canvas shower stalls. Nurse Crawford moved among them, offering towels and quiet words of comfort. She had seen men break down after battles, had comforted dying soldiers who cried for their mothers. This was different, but no less profound.

Women discovering that the enemy they had been taught to fear had chosen humanity over vengeance. Part four. By the afternoon of that first day, all 73 women had been through the bathing facilities. Captain Morrison had also arranged for clean clothing, a mixture of captured German civilian clothes and spare American uniforms that could be modified. It was not perfect, but it was clean.

And in those final weeks of April 1945, cleanliness represented a kind of civilization that had been absent from their lives for far too long. The transformation was remarkable. Women who had looked like hollow-eyed ghosts that morning now sat in the spring sunshine outside the barracks, wearing clean clothes, their hair damp, but finally free of lice and grime.

Some of them actually smiled tentative, uncertain smiles, but smiles nonetheless. Morrison walked among them with Vber translating, conducting informal interviews to determine who needed immediate medical attention, who had dependent somewhere in the chaos of collapsing Germany, and what skills or backgrounds might be useful in the processing ahead.

He stopped before Greta Hoffman, who sat with her back against the barracks wall, face tilted toward the weak sunshine. “You’re feeling better?” he asked through vber. Greta opened her eyes and studied the American captain. He was younger than she had first thought with the kind of face that probably smiled easily in peace time. “I don’t understand,” she said honestly. “We are your enemies. We are Germans.

” “After everything dot dot dot,” Morrison settled down on his heels so they were at eye level. “You were soldiers doing what soldiers do,” he said. “The war’s ending. What matters now is how we handle what comes next.” He paused, choosing his words carefully. I’ve seen too much dying, too much destruction.

When I have the chance to choose something different, something decent, I’m going to take it. Vber translated, and Greta felt something shift in her understanding of the world. She had been raised in the Hitler youth, had believed in the Fur’s mission, had served the Vermacht with dedication. The propaganda had been absolute.

Germany was fighting for survival against subhuman enemies who would show no mercy. Everything she had believed was collapsing as completely as the Reich itself. What will happen to us? She asked. You’ll be processed, interviewed, eventually released or transferred depending on your classification.

If you weren’t involved in war crimes, you’ll probably be sent to a civilian camp and then released when we’re satisfied you’re not a security risk. Morrison’s expression grew more serious. It won’t be comfortable and it won’t be quick, but you’ll be treated fairly. Across the compound, Margaret Klein was having a different conversation with nurse Crawford.

The two women, one German, one American, both nurses who had seen the intimate horrors of war, had discovered a common language that transcended nationality. “I worked on the Eastern front,” Margari said quietly in broken English she had learned before the war. I saw terrible things, things our soldiers did.

I tried to help, but dot dot dot dot do she fell silent, unable or unwilling to continue. Crawford nodded slowly. War makes monsters of people, she said. But it also shows us who chooses not to become one. You’re a nurse. You help people. That counts for something. As evening approached on that April day, the compound had taken on an almost surreal atmosphere of cautious normaly.

American soldiers had set up field kitchens and were preparing hot meals. Nothing fancy, just standard army rations, but hot food was hot food. The smell of cooking drew the German women like moths to flame, many of them having subsisted on scraps for days or weeks. Private First Class Robert Chun, a Chinese American soldier from San Francisco whose family had fought their own battles with prejudice back home, ladled stew into mess tins and handed them to the women with the same matter-of-act courtesy he would show to any other hungry person.

His presence in Asian men in American uniform, treating German prisoners with casual respect, was yet another contradiction to the racial ideology that had underpinned the entire Nazi regime. Elsa Brown accepted her tin of stew with trembling hands and found a spot to sit near the barracks.

The food was simple but nourishing as she ate slowly, savoring each bite. Beside her, a woman named Freda Adler, who had served as a telegraph operator, was crying quietly as she ate. “I thought they would kill us,” Freda whispered. “I was so sure we all were,” Elsa replied. Corporal Vber made his rounds, checking on the women and answering questions through the translator work that had become his primary duty. He stopped when he reached a small group that included Greta, Margari, and several others.

“Ladies,” he said in German, “Captain Morrison wants you to understand something important. Tomorrow, representatives from the International Red Cross will arrive to document your status as prisoners of war. You’ll be officially registered, which means your families, if they’re still alive and can be located, will eventually be informed that you’re safe.

The possibility of contact with families, of letting loved ones know they had survived, sparked the first real animation Morrison had seen from the group. Women began asking rapid fire questions. How long would it take? Could they write letters? What if their families were in the Soviet zone? Vber did his best to answer. Though the truth was that everything was chaos. Germany was being carved into occupation zones. Millions of people were displaced.

Communication systems had collapsed. Finding anyone in that mastrom would be difficult, but not impossible. As darkness fell, Captain Morrison stood at the edge of the compound with his sergeant, a gruff veteran from Alabama named Thomas Wright, who had fought across North Africa, Sicily, Italy, France, and now Germany.

You did a good thing today, Captain, Wright said quietly. Morrison shook his head. Just did what should be done. Nothing special about basic human decency. Maybe, Wright aloud, but it is special given everything. A lot of our boys, they’ve seen the camps. They’ve seen what these people’s army did.

They wouldn’t be so generous. Morrison understood what right meant. As American forces had pushed into Germany, they had begun liberating concentration camps Dau Binwald Bergen Baleen. The systematic horror of the Nazi regime’s crimes was being revealed in terrible detail. Many American soldiers confronted with evidence of genocide felt little sympathy for any German soldier or civilian.

The next morning, April 20th, 1940, favironically, Adolf Hitler’s 56th birthday, though none of the Americans knew or cared about this detailed Red Cross representatives arrived as promised. They were accompanied by a chaplain from the Third Army, a Catholic priest named Father Michael O’Brien from Boston, who had volunteered for military service despite being old enough to avoid it.

Father O’Brien moved among the German women with the gentle manner of someone accustomed to ministering to the suffering. He spoke no German, but he offered blessings and quiet presence, which in its own way transcended language. Several of the women raised in Germany’s Christian traditions before Nazism had tried to supplant them found unexpected comfort in his prayers.

The Red Cross documentation process was tedious but necessary. Each woman was interviewed, her information recorded, her status confirmed. The representatives, a mix of Swiss nationals and Americans, maintained strict professional neutrality, but even they seemed affected by the transformation.

They witnessed women who had been holloweyed with terror the previous day now sitting up straighter answering questions clearly showing the first fragile signs of hope. Greta Hoffman’s interview was conducted by a middle-aged Swiss woman named Claudia Meyer who had worked with displaced persons throughout Europe.

Meer took down Greta’s information with practice deficiency name, rank, unit, family status, home address. Your family? Meer asked in German. Do you know their status? Greta’s expression clouded. My parents are in Dresden. We’re in Dresden. I don’t know if they survived the bombing in February. My brother was in the Sixth Army at Stalingrad. I never heard from him after January 1943.

Meer made notes without judgment. Dresdon’s destruction in February had killed tens of thousands. The Sixth Army’s annihilation at Stalingrad in early 1943 had consumed an entire generation of German men. These were simply facts now, part of the vast accounting of the war’s cost. Well do what we can to locate your parents, Meyer said.

If they’re alive and can be found, we’ll facilitate communication. It was a small thing, but to Greta, it represented something enormous. the possibility that the world might actually continue, that there might be something beyond survival dayto-day. Meanwhile, Captain Morrison was dealing with a different problem.

Word of his treatment of the female prisoners had spread through the army’s communication network, and his commanding officer, Colonel Patrick Henderson, had arrived for an inspection. Henderson was a hard man, a career officer who had fought in the First World War and then returned for this one.

He had seen too much combat to be sentimental, but he was also fair-minded and intelligent. “Show me what you’ve done here, Captain,” Henderson ordered. Morrison walked him through the compound, explaining the bathing facilities, the food distribution, the medical screenings, the Red Cross documentation. Henderson observed everything in silence, his face unreadable.

Finally standing at the edge of the compound watching the German women going about their day with something approaching normaly Henderson spoke you know some of our boys wouldn’t approve of this they’ve seen the camps they’ve seen what these people were part of yes sir Morrison replied but these women weren’t running the camps they were soldiers support personnel most of them were just doing their jobs same as our WAC’s or nurses they don’t deserve to be brutalized is because of what their government did.

Henderson was quiet for a long moment. You’re right, he said finally. And frankly, this is probably good policy. We’re going to be occupying this country for years. Better to start establishing that we’re fair, that we follow our own rules. Might make the occupation easier, he paused. Also, it’s just the right thing to do.

Over the following days, the compound near Lindberg became an unexpected model for prisoner processing. Other units began hearing about Morrison’s approach, and several officers visited to observe and potentially replicate the procedures. Not everyone approved. There were plenty of soldiers whose hatred of Germany after what they had witnessed was absolute, but the official policy of the United States Army was clear.

Prisoners would be treated according to the Geneva Conventions, regardless of personal feelings. By April 25th, 1945, the group of 73 women had grown to nearly 200. As more female prisoners were brought in from surrounding areas, Morrison’s small operation expanded accordingly with additional medical personnel, supplies, and administrative staff assigned to manage the processing.

Greta Huffman found herself taking on an informal leadership role among the prisoners. Her relatively good English, learned in school before the war, made her useful as an additional interpreter, and her calm demeanor helped settle the newer arrivals who came in with the same terror the original group had experienced.

She stood with Corporal Vber one afternoon, helping him explain procedures to a group of 20 women who had just arrived from a Vermacht communications unit that had been overrun near Frankfurt. Tell them the truth, Greta said to Vber in English that was improving daily through constant use. Tell them the Americans are not what we were told. Tell them they will be treated fairly.

Some won’t believe it until they experience it themselves, but say it anyway. Vber smiled at her. You’ve come a long way from that first morning when you were pressed against the wall expecting to be shot. Greta returned the smile, though it carried a certain sadness. I’ve had to rethink everything I believed.

Not just about Americans, about everything. When you’re taught one thing your entire life and then reality contradicts it so completely dot dot dot she trailed off, unable to fully articulate the cognitive dissonance she was experiencing. Margariffy Klein had been wrestling with similar thoughts.

She sat with nurse Crawford during a break. The two women sharing coffee, real coffee, which the Americans seem to have an inexhaustible supply. I keep thinking about the Russian prisoners I saw, Margaret quietly. On the Eastern Front, how we treated them, how different it was from this, she gestured around the compound.

Why? Why this difference? Crawford considered the question carefully. I think, she said slowly. It’s about choosing what kind of country you want to be. America is imperfect. We’ve got our own sins, believe me. But we decided a long time ago that there are certain lines you don’t cross. Certain things you don’t do, even to your enemies. It doesn’t always work out that way, people being people. But it’s what we aim for.

Germany aimed for something different, Margariti said bitterly. We aimed for dominance, racial superiority. And look where it brought us. The two women sat in silence, contemplating the ruins of ideology and the strange grace of unexpected mercy.

By the first week of May 1945, the war was in its final death throws. Hitler had committed suicide in his Berlin bunker on April 30th. German forces were surrendering across Europe. On May 8th, victory in Europe day would be declared, marking the formal end of the European War. At the compound near Lindberg, these worldshaking events felt both distant and immediate.

The women knew Germany had lost that much had been obvious for months, but the formal confirmation brought its own complicated emotions. Relief that the fighting was over, grief for what Germany had lost, shame for what Germany had done, uncertainty about what would come next. Captain Morrison gathered the prisoners on the morning of May 8th with Vber translating to inform them officially that the war had ended.

“Ladies,” Morrison said, “As of today, the fighting in Europe is over. Germany has surrendered unconditionally to the Allied forces. You are still prisoners of war, but your status will be reviewed over the coming weeks and months. Many of you will likely be released to civilian life once we’re satisfied you pose no security threat.

” The announcement was met with a mixture of reactions. Some women wept, others simply nodded, having expected this for some time. Greta Hoffman felt an overwhelming sense of exhaustion, as though she could finally allow herself to acknowledge how tired she truly was. And that evening, there was an impromptu gathering in the compound. American soldiers and German prisoners sat together in loose groups, not quite fraternizing, but no longer maintaining strict separation. Private Chung shared cigarettes with some of the women who smoked. Nurse Crawford taught a few

basic English phrases to a cluster of curious prisoners. Father O’Brien led a prayer service that included both Americans and Germans praying for peace and healing in whatever form it might take. Corporal Vber found himself sitting with Greta, Margarvi, Elsa, and several others, talking about the future in a way that would have seemed impossible just weeks earlier.

What will you do? Greta asked him. When you go home, Vber shrugged. Go back to Milwaukee. Help run my father’s bakery, I suppose. Maybe go to college on the GI Bill if that works out. What about you? If my parents survived, try to find them. try to rebuild something from all this destruction.

Greta looked around at the compound, at the strange community that had formed there. Try to remember that people can choose to be decent, even when it would be easier not to be. The women who passed through the Lindberg compound in April and May of 1945 represented only a tiny fraction of the millions of German prisoners taken by Allied forces in the final months of the war. Their story was not unique.

Similar scenes of unexpected humanity played out across Germany as the American, British, and French forces grappled with the practical and moral challenges of occupation. But their story mattered nonetheless. recorded in the detailed reports Captain James Morrison filed with Third Army headquarters, in the logs maintained by the Red Cross representatives, in the letters that nurse Helen Crawford sent home to Tennessee, and in the memories the women themselves carried forward into the uncertain future. By June 1945, most of

the women from the original group had been processed and released. Greta Hoffman eventually found her parents alive in the ruins of Dresdon, though her brother had indeed perished at Stalingrad. She would spend the next several years in the British occupation zone, working as an interpreter during the reconstruction period, using the English she had polished during those weeks with the Americans.

Margaret Klene immigrated to the United States in 1950, sponsored by nurse Crawford and worked as a nurse in Tennessee until her retirement. The two women remained friends until Crawford’s death in 1983. Elsa Brown married a fellow German former soldier she met in a displaced person’s camp, and they built a quiet life in Bavaria, raising three children who would grow up in a very different Germany than their parents had known.

Captain Morrison returned to Ohio, became a teacher, and rarely spoke about the war. His children would discover his service records and the commendations he had received only after his death in 2006. Among his papers was a letter from Greta Hoffman, written in 1946, thanking him for choosing mercy when vengeance would have been easier. The canvas shower stalls, the hot water, the clean towels.

These small acts of basic human decency seem almost trivial in the vast narrative of World War II. Against the backdrop of industrial slaughter, genocide, and unprecedented destruction, what did a few hot baths matter? But to the women who received them, they mattered immensely.

They represented a choice to see the humanity in the enemy, to maintain civilized standards even when the world had descended into barbarism. They represented the possibility that the cycle of dehumanization and violence could be broken one small decision at a time. The story of the German P women at Lindberg is a reminder that even in the darkest chapters of human history, individuals have the power to choose dignity over degradation, mercy over vengeance.

that Captain Morrison and his men chose to treat these women with basic respect did not erase the horrors of the Nazi regime or absolve Germany of its crimes. But it did demonstrate that the victors could choose to be better than the defeated.

That the moral high ground was not simply claimed through military triumph, but through the decisions made in its aftermath. As Europe rebuilt from the ashes, as Germany confronted its terrible past, as the world tried to establish new international laws and norms to prevent such catastrophe from happening again, these small moments of humanity became threads in a larger tapestry.

They showed that another path was possible, that enemies could become neighbors again, that the future need not be defined solely by the violence of the past. The women who huddled in terror on April 19th, 1945, expecting death or worse, instead received warm baths and a chance at human dignity. That this surprises us that it seems remarkable rather than routine tells us how much war destroys our capacity to see each other as human beings.

Their story stands as a quiet testament to the possibility never guaranteed, always fragile, that we might choose to be better than our fears and hatreds would make us. In the end, that choice is all that separates civilization from chaos, mercy from cruelty, hope from despair.

News

CH2 . They B.α.п”.п”.ed Hιs I.l.l.e.g.α.l Cαrbιп”e — Uп”tιl He Dr/σp/ped 9 Jαpαп”ese Sп”!pers ιп” Twσ Dαys… Nσvember 1943. Bσugαιп”vιlle Islαп”d.

They B.α.п”.п”.ed Hιs I.l.l.e.g.α.l Cαrbιп”e — Uп”tιl He Dr/σp/ped 9 Jαpαп”ese Sп”!pers ιп” Twσ Dαys… Nσvember 1943. Bσugαιп”vιlle Islαп”d. The…

“Please Don’t Hurt Me” – German Woman POW Shocked When American Soldier Tears Her Dress Open… April 30, 1945. Near Leipig, Germany, cold morning air hangs over a crowded holding yard where German women stand in silence, waiting to learn their fate.CH2 .

“Please Don’t Hurt Me” – German Woman POW Shocked When American Soldier Tears Her Dress Open… April 30, 1945. Near…

CH2 . This 19-Year-Old Should’ve Been Court-Martialed — But Accidentally Saved Two Battalions… In just 90 seconds, Mitchell would make a catastrophic mistake, violating every rule, firing at the wrong target. And that mistake would save over 2,000 American soldiers and rewrite the way the US Army understood anti-aircraft warfare.

This 19-Year-Old Should’ve Been Court-Martialed — But Accidentally Saved Two Battalions… In just 90 seconds, Mitchell would make a catastrophic…

I married a homeless man everyone mocked and laughed at during the entire wedding… but when he took the microphone and spoke, he revealed a truth that no one could have expected and left the whole room in tears and sh0ck… When I told my family I was going to marry Marcus, they looked at me like I’d lost my mind.

I married a homeless man everyone mocked and laughed at during the entire wedding… but when he took the microphone…

My stepfather was a construction worker for 25 years and raised me to get my PhD. Then the teacher was stunned to see him at the graduation ceremony. That Night, After the Defense, Professor Santos Came to Shake My Hand and Greet My Family. When It Was Tatay Ben’s Turn, He Suddenly Stopped, Looked Closely at Him, and His Expression Changed.

My stepfather was a construction worker for 25 years and raised me to get my PhD. Then the teacher was…

My DIL Swore the Baby Was My Husband’s. He Smiled Proudly. Then ‘My Witness Walked in with One Paper…’ — And the Room Learned What REAL Destruction Looks Like…

My DIL Swore the Baby Was My Husband’s. He Smiled Proudly. Then ‘My Witness Walked in with One Paper…’ —…

End of content

No more pages to load