German Colonel Captured 50,000 Gallons of US Fuel and Realized Germany Was… December 17th, 1944.

0530 hours.

Hansfeld, Belgium.

The Tiger Tanks engine coughed, sputtered, then died.

SS Obashto Banura Yahim Piper slammed his fist against the turret hatch, the metallic clang echoing through the pre-dawn darkness.

His driver, Unshar Vber, attempted to restart the 700 horsepower Maybach engine.

Nothing.

The fuel gauge read empty.

Hair Oberanura Vber called up from his compartment, his voice tight with barely controlled panic.

The reserve tank is also dry.

Piper climbed down from his command tank, his boots crunching on the frozen Belgian soil.

Around him, the most powerful armored spearhead the Vermacht had assembled for Operation Watch on the Rine, the Arden’s offensive, sat motionless.

67 tanks, 149 halftracks, and nearly 5,000 of Germany’s most elite Waffan SS soldiers, all paralyzed by empty fuel tanks.

Through the morning mist, Piper could see the abandoned American position ahead, Hansfeld, a critical supply depot for the US 99th Infantry Division.

The Americans had fled so quickly they’d left fires still burning in oil drums, coffee still hot in metal cups, and there, lined up like a gift from the god of war himself, stood rows upon rows of jerry cans, thousands of them, the distinctive olive drab American fuel containers.

Piper approached slowly, almost reverently.

His agitant Halpedum Fura Hans Gruler pried open one can and sniffed benzene.

Hair Oashanfura, high octane gasoline.

As his men began the frantic work of refueling their vehicles, Piper walked among the stockpile counting.

The mathematics were staggering.

50,000 gallons enough to fuel his entire com grouper for the push to the Muse River.

Enough to potentially change the course of the offensive.

The Americans had abandoned more fuel in this single depot than most German divisions had received in the past six months.

But as Piper stood among this bounty, watching his men pour American fuel into German tanks, a crushing realization settled over him like the morning fog.

If the Americans could afford to abandon such quantities, if they could leave behind what Germany would guard with entire divisions, then this war was already over.

Germany hadn’t just miscalculated, Germany had fundamentally misunderstood the nature of its enemy.

6 months before Piper’s discovery at Hansfeld in June 1944, Albert Spear, Hitler’s Minister of Armaments and War Production, had presented the Furer with a report that should have ended all offensive operations immediately.

Germany’s synthetic fuel production, the lifeblood of the Vermacht, had been systematically destroyed by Allied bombing.

The loiner works which had produced 175,000 tons of fuel in April managed only 5,000 tons by September.

The burguous hydrogenation plants at Pitz, Blehammer, and Brooks were operating at less than 10% capacity.

The numbers told a story of inevitable defeat.

In 1944, the United States produced 1.8 billion barrels of crude oil.

Germany, including all synthetic production, and captured Romanian fields, managed 33 million barrels, less than 2% of American production.

The Third Reich was attempting to wage mechanized warfare with horsedrawn logistics.

While America was drowning its armies in petroleum abundance, Major Friedrich Simman of the Vermacht’s Logistics Command had calculated that the Arden’s offensive would require 4.5 million gallons of fuel to reach Antworp.

Hitler allocated 5 million gallons, but only half was actually delivered due to transportation problems.

The German high command was betting the entire offensive on capturing enemy supplies, a strategy that revealed terminal weakness rather than strength.

Read the full article below in the comments ↓

December 17th, 1944 0530 hours. Hansfeld, Belgium. The Tiger tanks engine coughed, sputtered, then died. SS Ober Storm Bunfura Yakim Pipper slammed his fist against the turret hatch. The metallic clang echoed through the pre-dawn silence like a gunshot. His driver, Unchar twisted the key.

Desperate, he tried to restart the 700 horsepower Mayback engine. Nothing. Dead silence. The fuel gauge stared back empty. With a tight voice, barely holding panic, Oba Storm Bunfura Vieber shouted from his compartment, “The reserve tank, it’s dry.” Pipper climbed down from his command tank, his boots crunching on the frozen Belgian soil.

All around him sat the most powerful armored spearhead the Vermacht had assembled for operation watch on the Rine. the Arden offensive, but motionless, stalled, helpless. 67 tanks, 149 halftracks, nearly 5,000 of Germany’s most elite Waffan SS soldiers, all paralyzed by empty fuel tanks.

Through the morning mist, Pipper’s eyes locked on the abandoned American position ahead. Hansfeld, a critical supply depot for the US 99th Infantry Division. The Americans had fled so fast, so recklessly. They’d left fires still burning in oil drums, coffee cups still warm, like soldiers caught mid meal. And then there it stood before him.

Rows upon rows of jerry cans, thousands of them, olive drab containers gleaming under pale light, like treasure, like gifts from the god of war himself. Pipper approached slowly, reverently. His agitant, Halpedum Furhan’s grer, pried open one can. He sniffed it, inhaled benzene and high octane gasoline like a starving mancatching scent of bread.

His men scrambled, hands trembling, as they began refueling their vehicles, desperate to sip life from the enemy’s veins. Pipper walked among the stockpile, counting. The mathematics were staggering. “50,000 gallons,” he murmured. “Enough to fuel his entire combat group for the push to the Muse River. enough to potentially change the course of the offensive. The Americans had abandoned more fuel in this single depot than most German divisions had received in the past 6 months.

But as he stood among this bounty, as he watched his men pour American fuel into German tanks, a crushing realization settled over him like the morning fog. Germany hadn’t merely miscalculated. Germany had fundamentally misunderstood the nature of its enemy. 6 months before Piper’s discovery at Hansfeld in June 1944, Albert Shpear, Hitler’s Minister of Armaments and Wall Production, had delivered a report that should have ended all offensive operations immediately.

Germany’s synthetic fuel production, the bloodline of the weremarked, had been systematically destroyed by Allied bombing. The refineries that once produced 175,000 tons of fuel in April managed only 5,000 tons by September. The hydrogenation plants at Pletz, Blackhammer, and Brookke were operating at less than 10% capacity. The numbers whispered inevitable defeat.

In 1944, the United States produced 1.8 billion barrels of crude oil. Germany, including all synthetic production and captured Romanian fields, managed 33 million barrels, less than 2% of America’s output. The Third Reich was attempting to wage mechanized warfare with horsedrawn logistics.

While America drowned its armies in petroleum abundance, Major Friedrich Simmon of the Wemarked Logistics Command had calculated that the Arden’s offensive would require 4.5 million gallons of fuel just to reach Antworp. Hitler allocated 5 million gallons, but only half was delivered due to transportation problems. The German high command was betting the entire offensive on capturing enemy supplies, a strategy revealing terminal weakness rather than strength.

The Americans, meanwhile, had constructed a petroleum pipeline system across France called Pluto, Pipeline Under the Ocean, and the Red Ball Express, a massive truck convoy system delivering 12,500 tons of supplies daily to the front lines. By December 1944, American forces in Europe were consuming 1.2 million gallons of fuel per day and receiving 1.4 million gallons, building reserves while fighting.

Yo Piper was no fool. At 29, he was one of the youngest regimental commanders in the Waffan SS, holder of the Knights Cross with oak leaves and swords, a veteran of the Eastern Front, where he had learned that in modern warfare, fuel was more precious than ammunition. His camp grouper had been designated the Sheree Punct, the decisive point of the entire Arden’s offensive.

On December 14th, 2 days before the attack, Piper attended the final briefing at Tondorf. General Sep Dietrich, commanding the sixth SS Panzer army, was blunt. You will have enough fuel to reach the Muse if you capture American supplies. The fuel allocation for Comf Group Piper was 31,000 gallons, enough for 50 miles of combat. The distance to the Muse was 65 miles.

The mathematics of failure were built into the plan from the beginning. As his column prepared to advance on December 16th, Piper issued strict orders. Tanks would operate in single file to conserve fuel. Engines would be shut off during any halt longer than 5 minutes.

The capture of American fuel dumps was priority one above even tactical objectives. The contrast with American operations could not have been starker. That same morning, Captain James Rose of the US 743rd Tank Battalion, stationed just 20 m from Piper’s starting position, recorded in his unit diary, received fuel resupply 8,000 gallons, third delivery this week. Storage tanks already at capacity.

December 17th, 1944. 0530 hours. Hansfeld, Belgium. The Tiger Tanks engine coughed, sputtered, then died. SS Ober Sharfurer Bura Yakim Piper slammed his fist against the turret hatch. the metallic sound cutting through the stillness like a warning shot. His driver, Unter Sharfurer Uver, twisted desperately at the ignition, attempting to restart the mighty 700 horsepower Mayback engine. Nothing, only silence.

The fuel gauge read empty. The reserve tank is also dry, over cold from his compartment, his voice taught with barely contained fear. Piper climbed down from his command tank, his boots crunched on the frozen Belgian soil like shattered glass. All around him, the Vermacht’s proud armored spearhead, 67 tanks, 149 halftracks, and nearly 5,000 of Germany’s most elite Vafen SS soldiers sat motionless. the greatest force assembled for operation watch on the Rine.

Paralyzed by empty fuel tanks. Through the morning mist, Piper’s eyes locked on the abandoned American position ahead. Hansfeld, a vital supply depot for the US 99th Infantry Division. The Americans had fled in such haste they’d left fires still burning in oil drums, coffee still steaming in metal cups, and and only in the wildest of hopes lined up like treasure from the gods.

Thousands upon thousands of olive drab American fuel containers, jerry cans stretching endlessly. Piper approached slowly, almost reverently. His agudant, Halpedium Furer Hans Gruler, pried open one can, bringing it close to his nose. He inhaled deeply benzene and high octane gasoline, his eyes widening as his men plunged into frantic labor, filling German tanks with American fuel.

Piper walked among the stacked containers, counting. The numbers were staggering. 50,000 gallons, enough to fuel his entire conf group for the push toward the Muse River, enough to possibly turn the tide. The Americans had abandoned more fuel here than entire German divisions had received in six months.

But as Piper stood amid this mountain of abundance, watching his men pour precious gasoline into their tanks, a crushing realization spread like fog across his mind. If the Americans could afford to leave this much behind, if they could abandon fuel that Germany would guard with entire divisions, then this war was already lost.

Germany hadn’t simply miscalculated, it had fundamentally misunderstood its enemy. 6 months before this morning at Hansfeld in June 1944, Albert Shpare, Hitler’s Minister of Armaments and War Production, had presented a report that should have ended all offensive operations. Germany’s synthetic fuel supply, the bloodline of its mechanized warfare, had been systematically destroyed by relentless Allied bombing.

The synthesis fuel plants that had produced 175,000 tons in April 1944 were churning out a mere 5,000 tons by September 1944. Hydrogenation plants at Pitts, Bllehammer, and Brook were operating at less than 10% capacity. The numbers told a story of inevitable defeat. In 1944, the United States produced 1.

8 billion barrels of crude oil. Germany, including synthetic production and captured Romanian fields, managed only 33 million, less than 2% of American output. The Third Reich was attempting to wage mechanized warfare on horsedrawn logistics. While America drowned its armies in petroleum abundance, Major Friedrich Simmon of the Vermacht’s Logistics Command calculated the Arden’s offensive would require 4.

5 million gallons to reach Antwelp. Hitler allocated 5 million gallons, but only half was delivered due to transport failures. The German high command was betting everything on capturing enemy supplies, a strategy bore not of strength, but terminal weakness. Meanwhile, the Americans had built a petroleum pipeline system called Pluto, Pipeline Under the Ocean, and the Red Ball Express, a convoy operation delivering 12,500 tons of supplies daily to the front lines. By December 1944, American forces in Europe consumed 1.2 2

million gallons daily and were receiving 1.4 million gallons. They stockpiled reserves even while fighting. Yahim Piper was no fool. At just 29 years old, he was one of the youngest regimental commanders in the Vahan SS, a holder of the Knights Cross with oak leaves and swords, and a veteran of the Eastern Front, where he learned firsthand that fuel was more precious than ammunition in modern warfare.

His kmph groupe had been designated the schwerpunct, the decisive point of the arden’s offensive. On December 14th, 2 days before the attack, Piper attended a final briefing at Tondorf. General Sept Dietrich, commander of the sixth SS Panzer Army, had been blunt. You will have enough fuel to reach the muse only if you capture American supplies.

The fuel allocation for Piper’s KF group was a mere 31,000 gallons, enough for just 50 m of combat operations. The muse lay 65 miles away. The mathematics of failure had been built into the plan from the start. As his column readied to move on December 16th, Piper issued strict orders. Tanks would travel in single file to conserve fuel. Engines would be shut off if halted for longer than 5 minutes.

Capturing American fuel dumps would be priority one above even tactical objectives. That same morning, Captain James Rose of the US 743rd Tank Battalion, stationed just 20 miles away from Piper’s starting point, recorded in his unit diary, received fuel resupply 8,000 gallons.

Third delivery this week, storage tanks already at capacity. December 16th, 1944 0530 hours. The German artillery barrage that launched Operation Watch on the Rine used more ammunition in 2 hours than Germany had allocated for entire campaigns earlier in the war. But this impressive firepower masked crippling shortages. Piper’s column finally began moving at 7 a.m. already behind schedule.

Roads that German maps promised as highways turned out to be narrow country lanes, many unpaved. Within hours, traffic jams snarled the convoy as vehicles designed for the Russian step struggled through Arden forests. At Lanzeroth, Piper’s first objective.

They ran into fierce resistance, not from an army, but from a lone American reconnaissance platoon of just 18 men. These brave souls held the most powerful German armored column at bay for nearly 10 hours. During this delay, vehicles idled endlessly, burning precious fuel. By the time they broke through and reached Hensfeld at dawn on December 17th, Piper’s column had covered only 20 miles and consumed 40% of their fuel.

At that rate, they would run dry before reaching even the halfway mark. The American supply depot at Hansfeld wasn’t even a major facility. It was a forward fuel point, a temporary station for the 99th Infantry Division. But what Piper discovered exceeded the fuel allotment of an entire German Panzer Division.

Halpedam Furahans Gruler later testified, “We found pyramids of jerry cans, each containing five gallons of gasoline stacked 3 m high for nearly 200 m. The Americans hadn’t even bothered to destroy them. The captured fuel was a high octane aviation blend mixed with motor fuel of 80 octane or higher. German vehicles, especially the finicky Maybach engines in Tiger tanks were designed for 74 octane.

The American fuel was so potent it caused engine problems in several vehicles. As his men refueled, more discoveries came to light. Sergeant Willilhelm Hoffman found shipping manifests in the depot office. He could read English, having worked in his father’s import business before the war.

The documents revealed fuel shipped from Texas to New York, across the Atlantic to Liverpool, through the channel to Normandy, and trucked 400 miles to Hansfeld. A journey of over 6,000 miles completed in under six weeks. I showed the papers to Orura Banner Piper, Hoffman recalled years later. He read them twice, then crumpled them. He said nothing, but his face went pale. We both understood what it meant.

Private Ernst Car stumbled upon stacks of Stars and Stripes newspapers dated December 15th, just 2 days old. The headlines boasted of a new fuel pipeline from Sherberg to Verdon capable of delivering 300,000 gallons daily. one pipeline supplying more fuel per day than Piper’s comp group could use in the entire offensive.

To grasp the shock of this discovery, one must understand the reality faced by the Veyart. In the final months of 1944, American bombing raids had cratered whale lines, destroyed storage depots, and ravaged refining centers at Mercerberg and Lona. Reports indicated fuel shortages, forcing commanders to ration gasoline, sometimes limiting field operations to a single attack before retreating.

By October 1944, some Panza divisions had fuel reserves for only 48 hours of combat. Despite these setbacks, the German high command launched the Arden’s offensive, betting that a sudden strike would cut Allied supply lines and reverse the tide of war. But Piper’s encounter at Hansfeld told another story.

His men gorged themselves on the spoils, but the victory tasted hollow. Even with captured fuel, the odds were stacked against them. As the morning sun rose over the Belgian fields, it cast long shadows over the abandoned jerry cans and over the hopes of an entire army. As December 18th, 1944 dawned, the chilling winds of the Arden swept through frostcovered trees.

Hansfeld’s supply depot had already become a ghost town, abandoned by retreating Americans, but its bounty was a cruel gift to the German soldiers. They stared at mountains of jerry cans stacked as if mocking them. By noon that day, Tiger tanks sat idling, their engines growling in frustration, consuming precious fuel while waiting to move forward.

Otto Dingler, the maintenance officer for the first SS Panza regiment, scratched his head, frustration etched across his face. By noon, he murmured, “We had consumed 67,000 gallons since the offensive began, and we had captured maybe 55,000. The arithmetic was unforgiving. It wasn’t just fuel anymore. It was hope, or the lack of it.” Across the lines, American forces had intercepted German radio transmissions.

The allies knew. General Courtney Hodges, stern and resolute, gave orders to all units. Enemy critically short of fuel. Destroy all gasoline stocks threatened by capture. It was a strategy born not from cruelty but necessity, a desperate shield against German advance. On that same day, American C47s, propeller engines whining like bees, flew 316 sorties to deliver supplies to Bastonier.

Among those sorties, 160,000 gallons of fuel were flown in, enough to keep aircraft roaring through the sky. The Allies were not just surviving, they were suffocating their enemy by abundance. By December 19th, the reality had set in. As German forces engaged defenders at Stalmont, the fuel crisis turned catastrophic. Tanks abandoned their posts.

Engines silent, not from enemy fire, but from thirst. The grim sight spread like frostbite across ranks. Colonel Hans Gruler later recounted how they scavenged tanks. “We drained the last fuel, maybe 200 gallons total,” he confessed, voice hollow with shame. The oburst stood there staring at the blackened engines, then ordered them destroyed.

Millions of Reich marks reduced to scrap, disabled by emptiness. Of 5,000 men who marched with Colonel Piper at the onset of the offensive, barely 770 returned. They had advanced 60 miles, seen victories, massacres, and ultimately the truth. The enemy’s strength was not bullets or bravery, but barrels of fuel.

That night, by firelight, soldiers huddled together, faces gaunt, no maps, no movement, no fuel, just silence, and the looming collapse. Even German commanders hardened by war felt the sting of hopelessness. General Hasso von Montiffuel later wrote, “When I learned Americans had destroyed 8 million gallons rather than risk capture, I knew the offensive had failed before it began.

” Captain Friedrich Fondenhur, interrogated after being captured, confessed, “Your soldiers throw away chocolate. My men haven’t seen chocolate in 2 years. You burn millions of gallons. We measure by the liter. How can we fight such abundance?” That one sentence encapsulated the abyss separating two worlds. By December 21st, the noose tightened.

Colonel Piper trapped at Leglaz could see American forces converging. The 31st Infantry Division, the 82nd Airborne, the Third Armored, all backed by unimeaginable reserves. His personal fuel reserves dwindled to about a thousand gallons. A single cup of coffee could consume more fuel than his entire force possessed. Patton’s third army pivoted north with 350,000 gallons of fuel in reserve.

Fuel that German planners deemed impossible to deliver in 3 days. On December 23rd, clear skies welcomed waves of aircraft. 2,000 sorties flew that day alone, each consuming more fuel than the Luftvafer had seen in months. P47 Thunderbolts consumed 300 gall per hour. B26 Marauders burned 200 gall per hour. A single day’s operations devoured more fuel than Germany’s entire offensive allotment.

By the night of December 23rd 24th, Colonel Piper abandoned his tanks. Under cover of darkness, his soldiers slipped through American lines on foot. of 119 tanks and assault guns that had begun the offensive, 39 remained, and even those were paralyzed. By dawn, they too were destroyed. Colonel Heints Gulis recalled the scene with a hollow laugh.

We drained the last fuel from all vehicles, maybe 200 gallons total. The Oberfer personally destroyed his command tank. Machines worth millions discarded like bones. Of 5,000 men, only 770 staggered home. They had marched, fought, and learned the cruel mathematics of industrial warfare. On December 26th, Field Marshal Walter Model received reports on captured American supplies. His chief of staff recorded his reaction.

He read the numbers twice, then trembled. 50,000 gallons at Hansfold. 2 million burned at Stavalo. 8 million destroyed rather than captured. Model whispered, “We are not fighting the same war. Even Hitler, presented with the facts, refused to believe them.

He dismissed photographs of burning dep depot as Hollywood illusions. But lower ranks they knew. Wilhelm Hoffman wrote to his wife, “Americans destroy more fuel daily than we receive monthly. They drive tanks like we march.” The revelation shattered illusions. The fuel crisis was not an isolated problem. It was the symptom of systemic collapse. By 1944, Allied bombing campaigns had crippled Germany’s synthetic fuel production by 90%.

The Luftvafa grounded aircraft for lack of aviation fuel. Pilot training dropped from 250 hours to just 60. German civilians hadn’t seen a private car since 1942. Farmers plowed fields with horses. Gasoline so precious that black market thefts were investigated down to the liter.

Meanwhile, the United States produced 67% of the world’s oil. The East Texas oil fields alone outproduced all German occupied Europe. American refineries operating at full capacity experimented with new byproducts simply because they had excess crude. Against this backdrop, Colonel Piper’s nightmare at Hansfeld was inevitable.

As the smoke of battle fades and the echoes of empty fuel tanks disappear into history, we remember not just the bravery of soldiers, but the relentless power of industry and how numbers, supplies, and sheer abundance shaped the outcome of a war. It’s in these stories of sacrifice, of perseverance, of impossible odds that we find lessons for today.

If this story touched your heart, if it opened a window into the lives of those who fought and endured, please support the channel by hitting that like button and subscribe to join us as we uncover more untold tales from the past. Every click helps us bring these stories to life for history to be remembered, not forgotten.

Thank you for listening, for sharing this journey with us, and for keeping the memories of courage alive. See you in the next story. Until then, take care and stay curious.

News

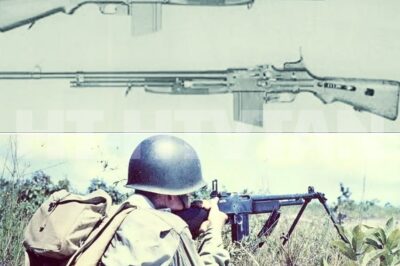

CH2 . Japanese Soldiers Couldn’t Believe One BAR Burst Cut Down An Entire Cave Squad… November 20th, 1943. 06 23 hours. Red Beach 2, Betio Island,

Japanese Soldiers Couldn’t Believe One BAR Burst Cut Down An Entire Cave Squad… November 20th, 1943. 06 23 hours. Red…

CH2 . US Pilots Examined A Captured Betty Bomber — Couldn’t Understand Why It Had Unprotected Fuel Tanks…

US Pilots Examined A Captured Betty Bomber — Couldn’t Understand Why It Had Unprotected Fuel Tanks… January 31, 1945. The…

CH2 . Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It… At 0730 hours on November 1st, 1943, Lieutenant General Alexander Vandergrift stood on the bridge of the command ship Macaulay, watching the coast of Bugenville appear through the morning mist. In 2 hours, 14,000 Marines of the Third Marine Division would hit the beaches at Empress Augusta Bay.

Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It… At 0730 hours on November 1st, 1943, Lieutenant General Alexander…

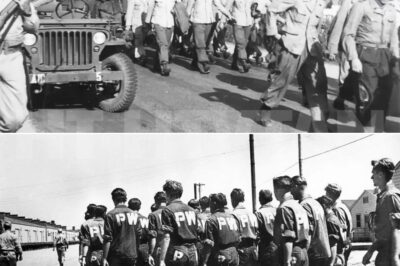

CH2 . German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary, recording words that would have earned him solitary confinement if discovered by his own officers. The Americans must be lying to us. No nation could possess such abundance while fighting a war on two fronts.

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943.Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas.The…

CH2 . When Allied Fighter-Bombers Pounced on Germany’s Elite Panzer Columns — And a Shocked General Watched His Armored Hammer Collapse Before It Ever Reached the Beaches…

When Allied Fighter-Bombers Pounced on Germany’s Elite Panzer Columns — And a Shocked General Watched His Armored Hammer Collapse Before…

Colonel Beat My Son Bloody and Called Me a Liar — Then 12 Minutes Later the Pentagon Called Him Asking If He Knew Who I Really Was…

Colonel Beat My Son Bloody and Called Me a Liar — Then 12 Minutes Later the Pentagon Called Him Asking…

End of content

No more pages to load