America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army…

June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped as North Korean fighters strafe the runway, destroying transports one by one. Enemy armor is twenty miles away and closing. North Korean radar picks up five unidentified contacts approaching from the sea. The flight leader squints through his La-7 canopy.

Whatever these Americans are flying doesn’t match any aircraft silhouette he’s been trained to recognize. The shape is wrong, grotesquely wrong. Two of something merged into one. Double where there should be single. A North Korean squadron that hasn’t lost an engagement in three days is converging on Suwon Airfield, where 1,527 lives now depend on these bizarre American contraptions.

The Peninsula Burns The Korean War began without warning. At dawn on June 25, 1950, ten divisions of the North Korean People’s Army launched a full-scale assault across the 38th Parallel. Columns of armor rolled south, smashing through thin South Korean defenses with precision that spoke of months of careful planning.

T-34 tanks crushed everything in their path while Soviet artillery pounded South Korean Army positions that had been pre-positioned under the cover of diplomatic talks. Civilians poured out of Seoul in panic, their belongings scattered across roads that trembled under the weight of enemy tanks.

ROK units fell back in disarray, their rifles useless against the mechanized forces they had never trained to face. Officers scrambled for radios that crackled with static and panic. Bridges were blown in desperate attempts to slow the advance, but it made little difference—the North Koreans had already poured through like water through a broken dam. Within 72 hours, Seoul was under enemy control.

Half a world away, the United Nations moved with unusual speed. On June 27, just two days after the invasion, the Security Council authorized military intervention. The chambers in New York echoed with urgent voices as diplomats realized this was no border skirmish. The U.S.

Seventh Fleet began deploying from Philippine bases, while British Far East Fleet warships took position off Korean waters. Both were cleared to engage North Korean targets without warning. But the war had already come to South Korea’s skies. As Seoul fell, Suwon Airfield, twenty miles to the south, became the last operational airstrip within striking distance. C-54 Skymasters flew in and out nonstop, their cargo holds crammed with evacuating U.S. diplomats, dependents, and contractors.

The tarmac was choked with departing aircraft and ground crews working under the constant threat of advancing enemy columns. Mechanics serviced engines while listening for the rumble of approaching tanks. Above this chaos, Soviet-built prop planes appeared like vultures. Yak-9s, nimble single-seat fighters armed with 20-millimeter cannon, and Il-10s, armored ground-attack aircraft bristling with machine guns and rockets, threatened evacuation routes and disrupted air operations.

From Japan, American fighter squadrons launched their first missions almost blind, rushing into a fast-moving battlefield where the front lines shifted by the hour and the skies held no clear master. Pilots clutched outdated maps while ground controllers shouted coordinates that were already obsolete. To protect this shrinking patch of ground, U.S.

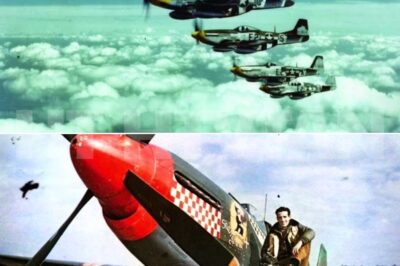

Far East Air Forces scrambled fighters from Japan: F-82 fighters, long-range F-80 jet interceptors, and piston-engine B-26 light bombers. Twin Mustangs Take Flight The first to arrive were F-82G Twin Mustangs—long-range, twin-fuselage escort fighters built for the Pacific but now called into action over a very different battlefield.

The Twin Mustang represented an unusual solution to the problem of long-range escort. Two P-51 Mustang fuselages were joined by a central wing and tail structure, creating a twin-engine fighter with remarkable endurance. Each fuselage mounted three .50-caliber machine guns, giving the aircraft devastating firepower at close range.

With a top speed of 465 miles per hour and a combat radius of 1,400 miles, it could reach Korea from Japanese bases and still have fuel for extended combat. However, the Twin Mustang’s unconventional design created unique challenges. The twin-fuselage configuration made it heavier and less maneuverable than single-engine fighters.

Its large profile presented a bigger target, and coordination between the pilot and radar operator required precise teamwork. Against nimble opponents, these disadvantages could prove costly. At first light on June 27, five F-82s lifted off from Japan, bound for Korean airspace. Their mission was urgent: escort four unarmed C-54 Sk

ymaster transports evacuating U.S. civilians from Kimpo Airfield. The Skymasters, crammed with diplomats, families, and staff, were flying slow and low—easy prey without protection. Leading the mission was Major James W. Little, a battle-tested World War 2 ace whose steady hands had guided bombers through flak-filled skies over Germany.

His flight entered Korean airspace under cloud-streaked skies, navigating through a theater that shifted by the hour. Around noon, five Lavochkin La-7s swept in from altitude, emerging at 10,000 feet. The North Korean pilots broke into a shallow dive, their radial engines screaming as they targeted the vulnerable Skymasters. The La-7, a late-war Soviet fighter, packed a punch with three 20-millimeter cannons and could reach 415 miles per hour in level flight.

Though slower than the Twin Mustang, it was highly maneuverable and packed heavier firepower per shot. At least one transport took hits before the fighters turned their sights to the escort. Major Little immediately called for return fire and fired the first burst himself, his six machine guns spitting tracers that cut into the formation as the La-7s split into two attacking elements.

The First Strikes The first confirmed elimination came when Lieutenant William G. Hudson, flying F-82 tail number 46-383, latched onto a La-7 climbing into a vertical escape. Hudson had learned his gunnery in the Pacific, where split-second timing meant the difference between returning home or becoming another statistic.

He fired into the fuselage and right wing, his tracers walking across the enemy fighter’s vulnerable fuel lines. The La-7 shuddered, then began trailing smoke. Its pilot, faced with certain destruction, chose survival over honor and bailed out. The parachute blossomed white against the Korean sky—the first North Korean aircraft destroyed by United Nations forces in the war.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Charles B. Moran, in F-82 number 46-357, found himself in serious trouble. His aircraft’s tail section had taken hits from 20-millimeter cannon fire, and the Twin Mustang briefly stalled as hydraulic fluid leaked from severed lines. Warning lights flashed red across his instrument panel.

He recovered just in time to catch another La-7 streaking ahead of him, its pilot apparently unaware of the pursuing American. Moran steadied his damaged aircraft and fired a sustained burst that found its mark. The La-7 erupted in flames and spun earthward, becoming the second victory of the engagement. Black smoke marked its grave in a rice paddy below.

Major Little, despite smoke beginning to fill his cockpit from an electrical fire, dove to assist his wingmen and lined up a third La-7. The enemy pilot was skilled, attempting a climbing turn that should have carried him to safety. But Little had fought over the Reich, where German aces had tried every trick in the book. He fired from close range, shredding the target’s wing and sending it tumbling toward earth.

Of the five North Korean fighters, three were destroyed in less than ten minutes. The remaining two broke contact and fled north, their radio chatter filled with urgent warnings about American capabilities. No American aircraft were lost, though damage was sustained across the formation.

For his leadership under extreme pressure, Major Little received the Silver Star. The first air battle was over, but even as the Twin Mustangs limped home, radar screens were lighting up with new contacts. Jet Age Supremacy News of the morning engagement spread through American command channels like wildfire.

By early afternoon on June 27, U.S. air controllers had issued a full alert over Seoul. North Korean fighters were still active in the area, and intelligence suggested they were massing for a major strike. This time, the response came not from Twin Mustangs but from jet fighters—the vanguard of postwar aerial warfare.

Four F-80C Shooting Stars from the 35th Fighter-Bomber Squadron were scrambled to intercept. Built by Lockheed, the F-80 was the United States’ first operational jet fighter, introduced at the tail end of World War 2 but never tested in major combat until now. The F-80C variant represented the pinnacle of first-generation jet technology.

Its single Allison J33 turbojet could push the aircraft to 600 miles per hour at sea level—nearly 200 miles per hour faster than any prop-driven fighter. Six .50-caliber machine guns clustered in the nose delivered punishing strikes with superior accuracy compared to wing-mounted weapons. However, early jets carried significant disadvantages.

The J33 engine was thirsty, limiting combat endurance to roughly 45 minutes. At low speeds, jet engines responded sluggishly, making the F-80 vulnerable during takeoff and landing. The aircraft also lacked the raw power-to-weight ratio of later jets, requiring careful energy management in combat. Compared to the Twin Mustang, the F-80 traded range and loiter time for pure speed and climb rate.

While the F-82 could escort bombers for hours, the Shooting Star was designed for rapid interception and quick strikes. Captain Raymond E. Schillereff led the flight of jets screaming toward the combat zone. His formation arrived on station just as another threat materialized from the north: eight Ilyushin Il-10s approaching low between Seoul and Incheon, their wings heavy with ordnance.

The Il-10 represented a different philosophy entirely. This rugged ground-attack aircraft, developed in the final year of World War 2, prioritized survivability over speed. Its heavily armored cockpit could withstand small-arms fire, while twin 23-millimeter cannons in the wing roots provided devastating ground-attack capability. With a top speed of only 340 miles per hour, the Il-10 was no match for jets in air-to-air combat, but its low-level attack capability made it a serious threat to airfields and ground forces.

Against the F-80, the Il-10’s disadvantages were glaring. The Soviet aircraft was 260 miles per hour slower, climbed poorly, and lacked the maneuverability to evade high-speed attacks from above. The North Koreans swept in low, attempting to catch American transports and grounded aircraft off-guard.

Before the F-80s could intervene, the Il-10s managed to destroy a parked ROKAF T-6 Texan trainer at Kimpo, sending up a plume of black smoke that marked their small victory. But the Shooting Stars were already diving. When Old Met New The engagement that followed marked the first true doctrinal clash between piston-engine attackers and jet-powered interceptors.

Captain Schillereff’s F-80s attacked without needing to dogfight, swooping down in controlled bursts from 15,000 feet, then climbing back to altitude using their superior thrust-to-weight ratio. The tactics were revolutionary—boom and zoom attacks that the Il-10s had no counter for. The North Korean pilots, trained in World War 2-era combat, found themselves facing a completely new type of warfare. Lieutenant Robert E.

Wayne struck first, diving on a pair of Il-10s breaking toward the Han River. His gun camera recorded the entire engagement: six streams of .50-caliber fire converging on the first target, then pivoting to the second as both enemy aircraft disintegrated under the sustained barrage. Moments later, Lieutenant Robert H.

Dewald caught a fleeing attacker in his sights and fired a sustained burst that sent it into a shallow dive and terminal impact. The Il-10’s armor, designed to protect against ground fire, proved useless against the concentrated firepower of jet-mounted weapons. Captain Schillereff himself downed a fourth with a clean, high-angle shot as it attempted to turn back north.

The enemy pilot never had a chance to return fire. Four North Korean aircraft were eliminated in total. The rest fled across the river and vanished from radar, their radio transmissions filled with panicked reports about “silver devils” that struck without warning. No further enemy air incursions were reported that day.

With the jets now in the fight, the U.S. had not just held the line—they had rewritten the rules of aerial combat entirely. The Sky Wars Begin More than 2,000 evacuees—1,527 of them U.S. nationals—escaped Suwon without injury from enemy aircraft, shielded by the fast, coordinated response of American fighters. But the numbers only hinted at what had shifted in the skies that day.

The engagement marked the U.S. Air Force’s full entry into the Korean air war—and its first true test in the Jet Age. The F-80 Shooting Star proved it could intercept and outfight both air and ground targets, while the twin-fuselage F-82 showed that piston-engine designs still had value in the right role.

Together, they formed a layered defense capable of striking quickly, climbing fast, and hitting hard across a range of threats. North Korean pilots, stunned by the technological mismatch, abruptly reduced daylight sorties. Their Yaks and Il-10s—once the terror of advancing columns—faded from the skies, unable to survive more than a few minutes in the open. With the airfield secured, U.S. and allied forces began operating with almost unrestricted freedom.

Fighters and bombers hit roads, bridges, and troop convoys, disrupting logistics and giving UN ground forces a fighting chance. Suwon had flipped the equation: air superiority now belonged to the United Nations. But air dominance didn’t mean safety. As American pilots celebrated, intelligence began to paint a darker picture.

North of the Yalu River, new formations were massing. Soviet advisors had arrived in theater, bringing advanced tactics and aircraft that were faster, stronger, and flown by veterans of World War II. Suwon bought time—but not certainty. It exposed both the power and the limits of early jet warfare. Victory had come through speed and surprise, but the next phase would demand more.

Behind Enemy Lines Captain Robert E. Wayne had already made his mark at Suwon Airfield, downing two enemy Il-10s with surgical precision. But weeks later, his story would become part of a historic chapter that would change combat rescue forever. On September 4, 1950, during a strafing run near Pohang, Wayne’s F-80 was hit by a withering barrage of ground fire.

The Communist forces had learned to concentrate their anti-aircraft weapons, turning Korean valleys into corridors of tracers and steel. Flames erupted from Wayne’s fuselage as hydraulic lines severed and fuel ignited. Severe burns seared his legs and arms as the cockpit filled with acrid smoke. Forced to bail out, he parachuted into a flooded rice paddy about five miles behind enemy lines.

The impact drove him deep into the muddy water, and when he surfaced, gasping and wounded, North Korean infantry were already closing in rapidly. Their shouts echoed across the paddies as they coordinated the hunt. Alone, injured, and exposed in open terrain, Wayne’s chances appeared grim. Above, the remaining F-51 Mustangs of his flight circled desperately, trying to keep hostile forces at bay with low-level strafing runs.

But fuel was running low, and dusk approached like a closing door. Time was running out, and conventional rescue seemed impossible. Then came 1st Lieutenant Paul W. van Boven, piloting an unarmed, unarmored H-5 helicopter dispatched from Pusan. The H-5, built by Sikorsky, was a small utility helicopter with a three-seat capacity and minimal armor protection.

Its single Pratt & Whitney R-985 radial engine could push the aircraft to a maximum speed of only 90 miles per hour—painfully slow by combat standards. With a service ceiling of 13,000 feet and a range of 300 miles, it was designed for medical evacuation and light transport, not combat rescue missions. Compared to the high-speed fighters dominating Korean skies, the H-5 was practically defenseless.

Its slow speed made it vulnerable to ground fire, while its lack of armor meant that even small-arms fire could prove fatal. However, the helicopter’s unique capability—vertical takeoff and landing—made it the only aircraft capable of extracting personnel from confined spaces. Van Boven, a former B-17 pilot who had been shot down and captured during World War 2, was determined not to let another pilot share his fate.

Corporal John Fuentez, the helicopter’s paramedic, was also onboard, checking his medical supplies as they approached the danger zone. The Impossible Rescue: Van Boven flew a cautious, circuitous route offshore to avoid the concentrated anti-aircraft fire that had already claimed one American aircraft that day. The small H-5 helicopter hugged the coastline, its rotor beating steadily as it approached the combat zone from an unexpected direction.

Over the radio, van Boven heard the F-51s peeling off to refuel, leaving just four planes on station. The window of opportunity was closing rapidly. Approaching from the sea, the helicopter appeared like a mechanical dragonfly against the growing twilight. Wayne, writhing in agonizing pain from his burns, frantically waved his white undershirt and began a desperate sprint toward the hovering aircraft.

His legs, seared by burning fuel, barely supported him as he stumbled through the flooded paddy. Enemy troops opened fire immediately with machine guns and rifles. Muzzle flashes erupted from concealed positions as North Korean soldiers realized what was happening. Bullets tore into the thin aluminum skin of the H-5, puncturing fuel lines and severing control cables.

The helicopter shuddered under the impact, its engine coughing as debris struck the rotor system. Without hesitation, Corporal Fuentez reached out through the open door and pulled the wounded pilot inside, even as enemy fire intensified around them. Wayne collapsed onto the cabin floor. Van Boven shoved the cyclic forward and lifted off, racing back toward the coastline as the helicopter bucked and vibrated from accumulated damage.

Though riddled with bullet holes, the H-5’s critical systems held together long enough to clear the beach and reach friendly territory. Against overwhelming odds, the rescue succeeded. This daring extraction was the first time a helicopter had pulled a downed pilot from behind enemy lines in combat—a breakthrough that marked the birth of modern combat search and rescue. Just as the Battle of Suwon Airfield had signaled the arrival of jet-powered dominance in the skies, the rescue of Captain Wayne showed that survival, too, was entering a new era.

News

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

CH2 . Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above Cape Bon, Tunisia.

Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above…

CH2 . Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles northwest of Lelay, New Guinea. The oil blackened hand trembled as a Japanese naval officer gripped the splintered remains of what had once been part of the destroyer Arashio’s bridge structure. His uniform soaked with fuel oil and seaater, recording in his mind words that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles…

CH2 . Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on April 18th, 1942 fundamentally altered the Pacific Wars trajectory, forcing Japan into a defensive posture that would ultimately contribute to its defeat.

Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on…

CH2 . German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of December 1944, the German war machine, a beast long thought to be dying, had roared back to life with a horrifying final fury. Hitler’s last desperate gamble, the massive Arden offensive, known to history as the Battle of the Bulge, had ripped a massive bleeding hole in the American lines.

German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of…

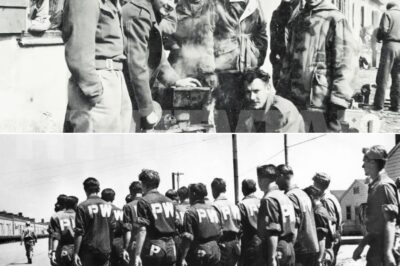

CH2 . German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary, recording words that would have earned him solitary confinement if discovered by his own officers. The Americans must be lying to us. No nation could possess such abundance while fighting a war on two fronts.

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States… June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street,…

End of content

No more pages to load